Research Article

Research Article

Regional Anesthesia Device Against the “Dead Ends”

in the Emergency Unit Peripheral Locoregional

Anesthesia in front of “ Therapeutic Impasse” in the

Emergency Operating Room

Nabil Jbili1*, Jaouad Laoutid Lotfi Bibiche1, Ayoub Maaroufi1, Abdelatif Diai1, Nourdin Jebbar1, Mounir

Khalil Mohamed Ouahidi2, Hicham Kechna1 and Jaouad Laoutid1

1Anesthesia pole of anesthesia resuscitation and emergency, University V Mohammed, North Africa

2Traumatology orthopedic surgery department, University V Mohammed, North Africa

Nabil Jbili1*, Jaouad Laoutid Lotfi Bibiche1, Ayoub Maaroufi1, Abdelatif Diai1, Nourdin Jebbar1, Mounir Khalil Mohamed Ouahidi2, Hicham Kechna1 and Jaouad Laoutid1

1Anesthesia pole of anesthesia resuscitation and emergency, University V Mohammed, North Africa

2Traumatology orthopedic surgery department, University V Mohammed, North Africa

Nabil Jbili, Military Hospital Moulay Meknes Ismail, University V Mohammed, North Africa.

Received Date: June 15, 2019; Published Date: June 28, 2019

Abstract

Locoregional anesthesia (ALR) is a technique that is increasingly expanding because of its safety and safety compared with general anesthesia and axial blocks. Locoregional anesthesia has several advantages in the context of emergency surgery. They simplify pre- and postoperative management for both the patient and the healthcare team. This is a prospective study conducted over a period of one year in the emergency room of the military hospital Moulay Ismail Meknes. Patients admitted for surgical limb emergencies with severe cardiorespiratory and metabolic impairment and in whom general anesthesia or peripullary anesthesia are considered to be at high risk were included. ALR device has been a very good alternative. Our study included 30 patients including 18 men and 12 women, the mean age was 72.5 years (63-82) all our patients were classified ASA IV. 20 blocks were made at the lower limbs and 10 at the upper limbs. Ultrasound detection was performed in 16 cases and the rest by neurostimulation. The interventions were carried out without affecting the previous state of the patients with good analgesia and satisfaction of the patients. ALR represents anesthetic technique of putting by its good tolerance. This interest differs in emergencies from fragile patients. All this justifies the need for good training and mastery of these techniques by all anesthetists’ doctors.

Introduction

The regional anesthesia is experiencing a big boom in the daily practice of intensive care anesthetists. The major interest of peripheral nerve blocks in emergencies lies in the absence of general repercussion [1], facilitating perioperative [2] with a better predictor of patient satisfaction and a major economic impact [3-4]. This technique can be an interesting alternative to general anesthesia and anesthesia perimedullary (APM) as part of the emergency, when they would be at risk [1,5,6] Within our training about 35% of surgical emergencies are performed under local anesthesia with approximately 90% of emergency concerning the members are performed under regional anesthesia device. We report through this study the experience of anesthesia pole and reanimation- emergencies involving the provision of ALR in the operating room when the emergency AG and / or epidural ALR can be dangerous.

Materials and Methods

This is a prospective study conducted in the operating room for emergencies Military Hospital Moulay Ismail in Meknes on a oneyear period extending from January 2016 to January 2017. Were included patients admitted for surgical emergencies and members with serious violations of cardiorespiratory and metabolic functions and for whom general anesthesia or spinal perished were deemed at risk where ALR device would be a good alternative. Exclusion criteria were patient refusal, allergy to local anesthetics, severe coagulation abnormalities. Peripheral nerve blocks were performed under standard monitoring, post-interventional surveillance room or neurostimulation or ultrasound guidance using local anesthetics like lidocaine 1% and 0.25% bupivacaine. The effectiveness of the block was assessed prior to admission of the patient to the operating room, in case of failure or insufficient block additional block was conducted Were assessed hemodynamics, respiratory, neurological, analgesia and patient satisfaction in per and postoperative.

Results

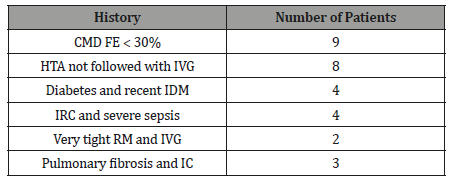

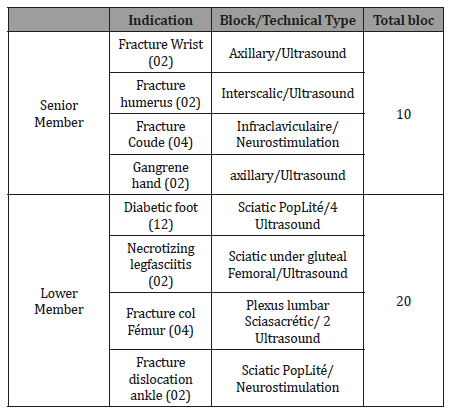

Our study includes 30 patients, including 18 men and 12 women with a sex ratio of 1.5 M / F, mean age 72.5 years (63-82). The evaluation of our patients pre anesthetic has classified all ASA III and IV (Table 1) with 4 presented difficult intubation criteria and 7 ventilation criteria difficult mask. 20 blocks were made to the lower limbs and 10 graduate members. The ultrasonographic guidance was conducted in sixteen cases and fourteen neurostimulation (Table 2). Local anesthetics used were 1% lidocaine and bupivacaine 0.25%, the volumes used ranged from 20 to 40ml.

Table 1: Patient Medical History Included in Study.

Table 2: Surgical Indications and Peripheral Nerve Block Types.

The number of requested specialized medical opinion in all our patients were limited to 4. The transthoracic echocardiography was not sought in any of our patients and the time interval between hospital admission and surgery was reduced by half in comparison with IV or ASA III patients who were operated on under general anesthesia or spinal anesthesia during the same period. The monitoring was standard in all cases, interventions were conducted without repercussion on the previous state of patients. Intraoperatively, changes in the FC were 6% (3-10%), blood pressure was 5% (2-8%) with respect to the intake values, the filling was provided by the saline with volumes ranging from 250 to 500cc and no patient needed vasoactive agents. No cases of respiratory distress, confusion or agitation in intraoperative or postoperative had been noted and none of our patients had need to stay in the intensive care unit after surgery.

In post-operative, all patients had a good quality of analgesia 6.5 (3-10) hours. At the rising of sensory block, VAS pain was estimated at 1 and calmed by paracetamol 1g infusion. After the 8th time, our patients had a mean VAS between 2 and 3, under control by paracetamol infusion and nefopam, only 2 patients required morphine iv 5mg and 5mg sc. The next day, our patients had a VAS pain˂3 and benefit of analgesia alone or paracetamol associated with codeine. Approximately 40% of patients expressed their discomfort with the realization of the block, but postoperative they were satisfied with the quality of algesia and no vomiting nausea. The anesthetic team was satisfied with fewer interventions in the operating room and even the bathroom SSPI. The stay in recovery room averaged 30 minutes, allowing patients to quickly join their relatives with less stress monitoring devices and a number of great satisfactions. The incidents were noticed a feeling of discomfort when performing in 12 patients, a vagal malaise and arrhythmia in three patients, and associated additives were further block in 02 patients and a supplement sedation in 02 case.

Discussion

The absence or near absence, under normal conditions of use and safety of systemic effects of plexus anesthesia, nerve blocks or local probably has a considerable advantage in very old topic that is in addition to one out of two, carrier serious underlying diseases [7]. A safe and effective anesthesia with minimal side effects is the basis for “accelerated protocols” or “fast tracking” preferring the peripheral blocks to the central blocks, avoid sedative premedication too, avoid high doses of opioids. These protocols should anticipate in particular post-operative analgesia and prevent possible emetic effects of anesthetic agents used [8]. General anesthesia in the context of the present emergency increased risk compared to that achieved for a scheduled act [1-9]. In addition, the trauma, pain or emergency treatments can decompensate preexisting pathology. The preoperative consultation emergency is difficult, and the data obtained are often limited and predictive criteria of ID are poorly adapted to the context of the emergency, which increases the risk of difficult intubation and trauma of the upper aerodigestive crossroads [10-11].

On the other hand, the sense of urgency against-indicates any prior preparation and the necessary recourse, at an AG in a rapid sequence induction with the potential risk of anaphylaxis, particularly succinylcholine [12-16]. On the other hand, Malignant hyperthermia is a potentially lethal complication triggered by exposure to halogenated and/or depolarizing neuromuscular blocking agents in receptor mutation carriers has ryanodine type I (RyR1). Local anesthetics can be administered safely in people likely to HM [17- 19]. Anesthesia peri medullary APM lead to a sympathetic block responsible for a decrease in venous return, cardiac output and 15 to 50% of cases of hypotension. Cases of cardiac arrest between 12 and 72 minutes after the intrathecal injection of local anesthetic were reported. These complications led SFAR against the state the APM in hemodynamic risk patients: shock, heart failure, absolute volume and/or relative, surgery bleeding risk, elderly patients, ASA III or IV patients. APM using the U are burdened with a risk of severe systemic and local neurological complications. In addition, the epidural use of morphine for analgesia exposed to the risk of respiratory distress opiate [5,6,20-22].

Spinal anesthesia continues, or better sequentially through a catheter, can be an interesting alternative to the price of technical difficulties limits the hemodynamic changes, particularly in relation to the single injection [23]. However, epidural anesthesia is little room in an emergency, its anesthetic quality is lower compared to spinal anesthesia, while the hemodynamic effects are comparable [12]. The fragile patient anesthesia can cause an adverse impact especially since it has impaired cardiac function and / or blocking treatment countervailing mechanisms involved in the shock (b-blockers, inhibitors converting enzyme); [24-25].

The evaluation of heart disease patients is based on resting echocardiography. However, in the emergency context it is a work overload and management of late. In addition, it detects abnormalities are not predictive of cardiovascular risk [26,27]. Patients at risk must receive invasive monitoring and a specific care pathway for continuing monitoring began intraoperatively. Traditional post-interventional monitoring facilities are probably insufficient and monitoring units or intensive care units, have their place in these patients [28]. In our study, all patients had severe comorbidities with precarious and polymedicated hemodynamics were operated under standard monitoring and none of them has required a stay in intensive care unit. In patients with heart disease, Regional anesthesia allows them to benefit from perioperative analgesia benefits and possible avoidance of general anesthesia, the latter, although very safe, can cause hemodynamic changes. The prospect of regional anesthesia and analgesia allows the patient to avoid hemodynamic fluctuations, minimizing the risk of decompensation [29].

The indications for emergency ALR are many, both in the upper limb, lower limb or at the front. This type of anesthesia is very promising in frail patients, avoiding the risks of general anesthesia [12]. In addition, the maintenance of consciousness during an ALR allows careful monitoring of patients [30]. Interventional post room monitoring is simplified in these procedures [2] with an early exit and a better indicator of patient satisfaction [3-4]. This is the case of our study, peripheral ALR avoids general anesthesia and epidural our patients who were operated without hemodynamic or respiratory impact while enjoying analgesia quality and quickly regained their autonomy initial. In trauma cases requiring surgery, the early use of local anesthetics or long-acting peripheral nerve catheter eliminates the urgency of related organizational problems (duration not always known preoperatively with certainty, order permanently patients changed because of the more or less urgent intervention, late release of operating rooms...). This early analgesia makes the expectation of the patient and easier workload in nursing care smaller [12].

In the lower limb, the femoral nerve block or block iliofascial is very useful for analgesia prior thigh, femur and knee, it can be done in-hospital [31] and by non-anesthesiologists [14]. It provides quality analgesia in the emergency services. Regional anesthesia has proven to be an excellent anesthetic modality for upper extremity surgery. This concerns relief lasting pain, reduce side effects associated with opioids in the first 24 hours after surgery [32-35] Emergency surgery may benefit from the input of very distal ALR techniques blocks ankle or wrist blocks of the branches of the trigeminal nerve for facial wounds. This type of ALR is less than algogenic subcutaneous local anesthetic blocks and often more effectively a larger area with a lower amount of local anesthetic. The benefit is obvious to almost zero risk and ambulatory output management is facilitated [12] ALR provides good prolonged postoperative analgesia at rest, but especially the mobilization compared to that of morphine [36] with a lower consumption of analgesics and morphine [12,37]. The average effective duration of post-operative analgesia provided by the peripheral regional anesthesia was superior to 6 hours in our study, then it was relayed by the paracetamol alone or in combination with nefopam. Only two patients required morphine after the 8th hour.

Note the exceptional rarity of allergy to local anesthetics if we compare the small number of cases published in the considerable number of regional anesthesia performed annually [38-39]. In emergency, priority should be given regional anesthesia and general anesthesia avoiding muscle relaxants and drugs histaminolibérateurs [40-41]. Other benefits of the ALR, one can mention the likely reduction of post-traumatic stress, improve local microcirculation induced by vasoplegia (sympathetic block), the prevention of chronicity of pain. Furthermore, this technique anesthetic few cons-indications: patient refusal, infection at the puncture site, existing neurological disorders [36]. To save time, nerve blocks should be performed outside the operating room. In this case, the cost and time are saved and efficiency is maximized [35] and the post-anesthetic awakening, consumer of time, space, staff or medical devices and reduced, this would have the effect of improving patient comfort and make room for them in SSPI monitor the highest risk patients [8]. The anesthesia should be performed in a monitored patient and monitored during and after the completion of the act [36] The evaluation of the quality of anesthesia should be in each of nervous territories likely to be blocked because it allows diagnosis possibly additional feedback. The total or partial failure must be diagnosed prior to surgery [3].

Regarding the local anesthetics mepivacaine short duration of action will be preferred when rapid monitoring is necessary. Use of levobupivacaine or ropivacaine better (less cardiotoxic) ensures prolonged analgesia can be maintained electronically or elastomeric pump. The PCA mode to reduce the consumption of local anesthetic compared to continuous mode, while ensuring an adequate level of analgesia administered by the patient who fits additional bolus [12].

The posture must be carefully studied to be comfortable as well for the realization of the block for surgery, and this can take time, and to provide an associated sedation [7]. Complications associated with regional anesthesia present a rare but significant risk of systemic toxicity. The G is responsible for neurological complications and/or cardiac complications. Cardiotoxicity is more important for bupivacaine, intermediate for levobupivacaine and ropivacaine for lower [9,15]. Other risks associated with regional anesthesia are hematoma, infection, and complications such as pneumothorax [36,42,43] Should be aspirated prior to injection and after each stop to not inject intravascular. Fortunately, one of the advantages of ultrasound guidance in the use of regional anesthesia was the reduced need for large volumes [44].

Peripheral neurologic complications are more common after AG after ALR. The surgery and the patient’s intraoperative positioning are potentially providers of postoperative nerve damage. The potentially deleterious influence of the anesthetic block of altered nerve fiber has not been demonstrated. No study exceeds the level of evidence IV or V. Most opinions are extrapolated from studies of epidural analgesia [3].

There are no cons absolute contraindication to practice a block device in a patient with a stable neurological condition and properly labeled. Diabetes and metabolic damage and central neuropathy (multiple sclerosis) are not an against-indication to block devices subject to an accurate diagnosis [3].

When neurological deficits of traumatic or vascular stabilized for several months, a conduction block does not present any specific risk, but requires a neurological exam carefully compiled in medical observation and discussion of the benefit/risk of the ALR [3]. None of our patients had an incident or accident neurological or cardiovascular toxicity of local anesthetics used It does not exist in the literature, the work formally finding a benefit in terms of mortality ALR compared to the GA, as in programmed in [12] Emergency surgery. Outside the spinal techniques (epidural, spinal) responsible for drops in sometimes dramatic blood pressure in trauma patients, hypovolemic and / or significant cardiovascular history, keep in mind the possibility of occurrence of similar complications with peripheral blocks perimedullary (lumbar plexus block by posterior approach, paravertebral block). Indeed, spreading always possible in the epidural space of the local anesthetic needs to take into account the same as those againstindications of spinal blocks. Therefore, these blocks are used nowadays in emergency [12].

This is the risk of failure which is the main drawback of the ALR urgently. Blocks of supplements made distally of great service in a number of cases before resorting to the GA. It is therefore fundamental that the ALR are performed by experienced operators. Similarly, the choice of blocks must favor among the appropriate techniques, the simplest and those controlled [12]. Despite their safety and general lack of impact (central neurological, hemodynamic, ventilatory) peripheral blocks [45] Postoperative surveillance is required in all cases. The research must be systematic neurological damage, especially as their preoperative neurological signs. The deficit secondary appearance in a nervous territory requires the use of additional tests to determine the exact nature and location of the lesion, which is not systematically related to the ALR (surgical injury, compression, withers pneumatic...) [12].

Conclusion

ALR has peripheral simplifies the anesthetic management of patients while ensuring a good post-operative analgesia and facilitate the work of medical teams without forgetting the economy of cost and time. This interest is reflected more in frail patients and unstable hence the importance of training and continuing education to better control and safe use.

Acknowledgement

None.

Conflict of Interest

No conflict of interest.

References

- Edwards AE, Seymour DG, JM McCarthy, Crumplin MK (1996) A 5-year survival study of general surgical patients aged 65 years and over. Anesthesia 51: 3-10.

- Fuzier R, Cuvillon P, Delcourt J, Lupescu R, Bonnemaison J, et al. (2007) ALR orthopedic device multicenter evaluation of practices and business impact of the SSPI. Ann Fr Anesth Reanim 26(9): 761-768.

- (2003) Recommendations for clinical practice. In: Sfar (edt.), Peripheral block members in adults. Ann Fr Anesth Reanim 22: 567-581.

- (2017) Recommendations formalized Experts SFAR. Recommendation on anesthesia in the elderly: the case of fracture of the proximal femur.

- SFAR (2006) The perimedullary blocks in adults. Clinical Practice Recommendations.

- Auroy Y, Benhamou D, Bargues l (2002) Major complications of regional anesthesia in France. The SOS regional hotline service. Anesthesiology 97(5): 1274-1280.

- Frédérique Servin, Philippe Juvin (2002) Anesthesia in the elderly.

- M Gentili, Plantet F, Delaunay L (2014) Ambulatory and surgical emergencies. The Practitioner anesthesia Resuscitation 18: 272-276.

- Lienhart A, Auroy Y, Pequignot F (2006) Survey of Anesthesia-related mortality in France. Anesthesiology 105(6): 1087-1097.

- (2006) French Society of Anesthesia and Intensive Care expert lectures difficult intubation. Short text.

- Lacau St Guily J, Drink Bertrand D, Monnier P (2003) lesions related oro and nasotracheal intubation and alternative techniques: lips, nasal and oral cavities, pharynx, larynx, trachea, esophagus. Ann Fr Anesth Reanim 22: 81s96s.

- Fuzier R, Richez AS Olivier (2007) locoregional anesthesia in emergency. Resuscitation 16: 660-664.

- Mertes PM, Karila C, Demoly P, Auroy Y, Ponvert C, et al. (2011) What is the reality of allergic risk in anesthesia? rare events monitoring methodology. Classification, Impact, Clinical Aspects (immediate and delayed), Morbidity and mortality, Substances responsible, Recommendations formalized expert, Annals of Fr Anesth and Réanim 30: 223-239.

- A Baumann, Studnicska D, Audibert G, Bondar A, Y Fuhrer, et al. (2009) Refractory anaphylactic cardiac arrest after succinylcholine administration. Anesth Analg 109: 137-140.

- Hepner DL, Castells MC (2003) Anaphylaxis During the perioperative period. Anesth Analg 97(5): 1381-1395.

- Johansson SG, Bieber T, Dahl R, Friedmann PS, Lanier BQ, et al. (2004) Revised nomenclature for allergy for global use: Report of the Nomenclature Review Committee of the World Allergy Organization, October 2003. J Allergy Clin Immunol 113: 832-836.

- H Rosenberg, Davis, James D (2007) Malignant hyperthermia. Orphanet J Rare Dis 2(21): 1186-1256.

- SFAR (2007) Malignant hyperthermia of anesthesia.

- MHAUS (2007) Emergency therapy for malignant hyperthermia.

- V Moen, Dahlgren N, Irestedt L (2004) Severe neurological complications after central neuraxial blockades In Sweden 1990-1999. Anesthesiology 101(4): 950-959.

- Aromaa U, Lahdensuu M, D Cozanitis (1997) Severe complications associted with epidural and spinal anesthesia in Finland 1987-1993. A study is based insurance claims. Acta Anesthesiol Scand 41: 445-452.

- Baer (2006) Post dural puncture bacterial meningitis. Anesthesiology 105(2): 381-393.

- Favarel JF Garrigues, Sztark F, Petitjean ME, Thicoipe M, Lassie P (1996) Hemodynamic effects of spinal anesthesia in the elderly: single dose titration versus through a catheter. Anesth Analg 82: 312-316.

- Elmanser D (2016) Anesthesia of the patient in shock. Anesth Reanim.

- Coriat P (1997) Circulatory stress and cardiac risk of anesthesia.

- Abraham P, Piriou V, Fellahi JL (2016) Preoperative cardiac evaluation in non-cardiac surgery. EMC Anesthesiology 13(4): 1-11.

- Schaeffer E, Masson Y, Paries million Raux M (2016) Preoperative workup. EMC Treaty Akos Medicine 11(3): 1-5.

- Piriou V, Imhoff E (2016) cardiac risk in general surgery: Evaluation and management. SFAR.

- EC Pierce (1996) The 34th Rovenstine Reading. 40 years behind the mask: safety revisited. Anesthesiology 84: 965-975.

- Carli P (1990) Emergency Trauma Anesthesia: general anesthesia or locoregional anesthesia? In: Sfar (edt.), discount conferences. XXXIII National Congress of Anesthesia and Intensive Care. Paris: Masson pp:219-227.

- S Lopez, Big T, Bernard N, Plasse C, Capdevila X (2003) Fascia iliaca compartment block for femoral bone fractures in prehospital care. Reg Anesth Pain Med 28: 203-207.

- Neal JM, Gerancher AD Hebl JR (2009) Upper extremity regional anesthesia: essentials of our current understanding 2008. Reg Anesth Pain Med 34: 134-170.

- Klein SM, Evans H, Nielsen KC (2005) Peripheral nerve technical block for ambulatory surgery. Anesth Analg 101: 1663- 1676.

- Hadzic A, Arliss J Kerimoglu B (2004) Comparison of infraclavicular nerve block versus general anesthesia for hand and wrist-day case surgeries. Anesthesiology 101: 127-132.

- McCartney CJ, Brull R, Chan V (2004) Early but no long-term benefit of regional Compared with general anesthesia for ambulatory hand surgery. Anesthesiology 101: 461-467.

- Levy F, Losser Local anesthesia, locoregional or general.

- E Gaertner (2009) Recommendation formalized expert, peripheral nerve blocks Indications. French Annals of Anesthesia and Intensive Care 28: e85-e94.

- Mertes PM, Malinovsky JM, Mouton Faivre C, Boyer Bonnet MC, Benhaijoub A, et al. (2008) Anaphylaxis to dyes During the perioperative period: carryforwards of 14 clinical cases. J Allergy Clin Immunol 122: 348-352.

- Mertes PM, Lambert M, Gueant Rodriguez RM, Aimone Gastin I, Mouton Faivre C, et al. (2009) Perioperative anaphylaxis. Immunol Allergy Clin North Am 29: 429-451.

- Recommendations formalized text expert short (2011) French Society of Anesthesia and Resuscitation (SFAR), French Society of Allergology (SFA). allergic risk prevention peranesthésique. French Annals of Anesthesia and Intensive Care 30: 212-222.

- Mertes PM, Demoly P Malinovsky JM (2012) Anaphylactic and anaphylactoid complications of general anesthesia. EMC Anesthesiology 9(2): 1-17.

- Capdevila X, Dadure C (2006) Peripheral nerve blocks complications. The anesthesia practitioner resuscitation Elsevier Masson SAS.

- Auroy Y, Benhamou D, Bargues L (2002) Major complications of regional anesthesia in France: The SOS Regional Anesthesia Hotline. Anesthesiology 97: 1274-1280.

- Ponrouch M, Bouic N, Bringuier S (2010) Estimation and pharmacodynamic consequences of the minimum effective anesthetic volumes for median and ulnar nerve blocks: a randomized, doubleblind, controlled comparison entre ultrasound and nerve stimulation guidance. Anesth Analg 111: 1059-1064.

- Mirek S, Freysz (2017) locoregional analgesia emergency in adults. European Journal of Emergency and Intensive Care 29: 16-30.

-

Nabil Jbili, Jaouad Laoutid Lotfi Bibiche, Ayoub Maaroufi, Abdelatif Diai, Nourdin Jebbar, Mounir Khalil Mohamed Ouahidi, et al. Regional Anesthesia Device Against the “Dead Ends” in the Emergency Unit Peripheral Locoregional Anesthesia in front of “ Therapeutic Impasse” in the Emergency Operating Room. Anaest & Sur On J. 1(1): 2019. ASOAJ.MS.ID.000504.

-

Analgesia, Hemodynamic, Echocardiography, Vasoplegia, Neurological signs, Trigeminal nerve, Extremity surgery.

-

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.