Research Article

Research Article

Do Folk Medicinal Practices of Bangladesh Have any Scientific Value? an Appraisal of Phytotherapeutic Practices of a Rural Folk Medicinal Practitioner

Jakera Shakera1, Rony Mandal1, Nasrin Akter Shova1, Nargis Ara2, Tanjina Akter2, Khoshnur Jannat1 and Mohammed Rahmatullah1*

1Department of Biotechnology & Genetic Engineering, University of Development Alternative, Bangladesh

2Department of Pharmacy, University of Development Alternative, Bangladesh

Mohammed Rahmatullah Dean, Faculty of Life Sciences, University of Development Alternative, Lalmatia, Dhaka-1207, Bangladesh.

Received Date:September 03, 2019; Published Date: September 09, 2019

Abstract

Folk medicine is generally considered as phytotherapy practiced by an individual or a group of individuals, who do not need to obtain any institutional training or approval to practice, and who can practice on a regular basis or as a hobby. In Bangladesh, folk medicinal practitioners (FMPs) are a varied lot using a bewildering variety of plants to treat almost every ailment suffered by human beings. It is the general opinion of allopathic doctors and the affluent section of the Bangladeshi population that FMPs practice nothing but quackery and their main objective is to deceive people. It was the objective of the present study to document the phytotherapeutic practices of a village FMP of Bangladesh and to search through the scientific literature to determine whether the plants used by the FMP had any scientific validation behind their uses. Our Results and Discussions clearly demonstrate that folk medicinal plants have substantial scientific validations, which possibly has come through practice of folk medicine and honing of such practices over thousands of years and transmission of acquired knowledge to successive generations initially orally and then through written methods.

Keywords: Folk medicine; Scientific validation; Phytotherapy; Kushtia; Bangladesh

Introduction

Folk medicine (FM) is practiced by part-time or full-time folk medicinal practitioners (FMPs) in Bangladesh, utilizing for the most part plant-based remedies as their modus operandi for treatment of practically all ailments suffered by the Bangladesh people. FM is not unique to Bangladesh; it is present in practically every country of the world under different names or guises like home remedies, herbal remedies, etc. With time, FM can even take on a more formal form in which cases they are known as Ayurveda and Siddha (in India), Unani (in Greece) or Kampo (in Japan). People of Thailand are said to use herbal remedies since the Sukothai period (1238- 1377) [1]. However, the use of plants as medicines dates back to much earlier times. Radiocarbon dating shows that plants were cultivated in ancient Babylon (present Iraq) more than 60,000 years ago [2]. It is possibly safe to say that human beings have suffered from ailments since their very advent and have tried to cure such ailments possibly from the earliest human ancestors about 6-7 million years ago – the Australopithecines [3]. It is to be taken into account that the great apes and other animal species instinctively partake of some plants for medicinal purposes [4], and the earliest hominids could have easily caught onto this ‘cure’ system.

Ethnomedicine is still somewhat a new concept in Bangladesh even though the country possibly has more than a hundred tribes and over 5500 plant species. With the emergence of new diseases, drug-resistant vectors, and adverse effects of allopathic medicines, even modern doctors and scientists are giving FM a second look. There is a desperate need for new drugs to treat diseases like malaria and antibiotic-resistant microorganisms; plant kingdom, which has always been a source for new drugs [5], can also be the sources for novel drugs at present and in the future. In this instance, FMs can play a key role in guiding scientists to plants with strong potential as sources of novel and efficacious drugs, for from constant practice they can be the most knowledgeable persons on therapeutic properties of plants. Another possible advantage of FMs and tribal medicinal practitioners (TMPs, really tribal FMs) is that due to regional diversity or simply knowledge-based diversity, there can be huge variations between the selections of plants to treat the same disease from one FM to another, even though both FMs may be practicing quite close to one another [6-35]. This opens up alternate sources of discovering possible new drugs with less or no adverse effects. FM is generally dismissed by the allopathic doctors and the affluent section of the population as ‘quackery’. Our objective was to select at random a FMP, and see whether the FMP’s therapeutic uses of plants are supported by available scientific reports on the pharmacological activities of the plant and reported phytochemicals in the plant with appropriate therapeutic benefits. As such we chose a rural FMP for such FMPs, if any, may be more prone to such ‘quackery’.

Methods

The FMP was named Shahidul Islam, male, middle-aged, that is around 45 years of age. He practiced in the villages of Daulatpur Upazila (sub-district) in Kushtia district, Bangladesh. The subdistrict had a total number of 246 villages with an area of 468.76 square kilometer and a population density of 946 per square kilometer. Kushtia district is located in between 23°42’ and 24°12’ north latitudes and in between 88°42’ and 89°22’ east longitudes with an area of 1621.15 sq km. The practice of the FMP was to travel in the various villages searching for prospective patients and also practicing from home at Gobrapara village, Kushtia district. Prior informed consent was initially obtained from the FMP. The FMP was informed the reason for our visit and consent obtained to disseminate any information provided including his name both nationally and internationally. Actual interviews were conducted in the Bengali language, which was spoken fluently by the FMP as well as the interviewers, the language being the mother tongue of FMP, villagers and the interviewers. The interviews were conducted with the help of a semi-structured questionnaire and the guided field-walk method of Martin [36] and Maundu [37]. In this method the FMP took the interviewers to spots from where he collected medicinal plants for therapeutic purposes. (In Bangladesh every village will have fallow land, secluded spots, small water bodies, or a strip of forest from where FMPs and folk herbalists collect their medicinal plants.) The FMP showed the interviewers a number of plants and described their therapeutic uses. All plant specimens shown by him were collected on the spot, pressed, dried and brought back to Dhaka for identification by a competent botanist. Voucher specimens were deposited with the Medicinal Plant Collection Wing of the University of Development Alternative. Secondary information on the pharmacological properties and phytochemicals of the plants used by the FMP were obtained from papers in PubMed, SCOPUS and Google Scholar abstracted journals.

Results and Discussion

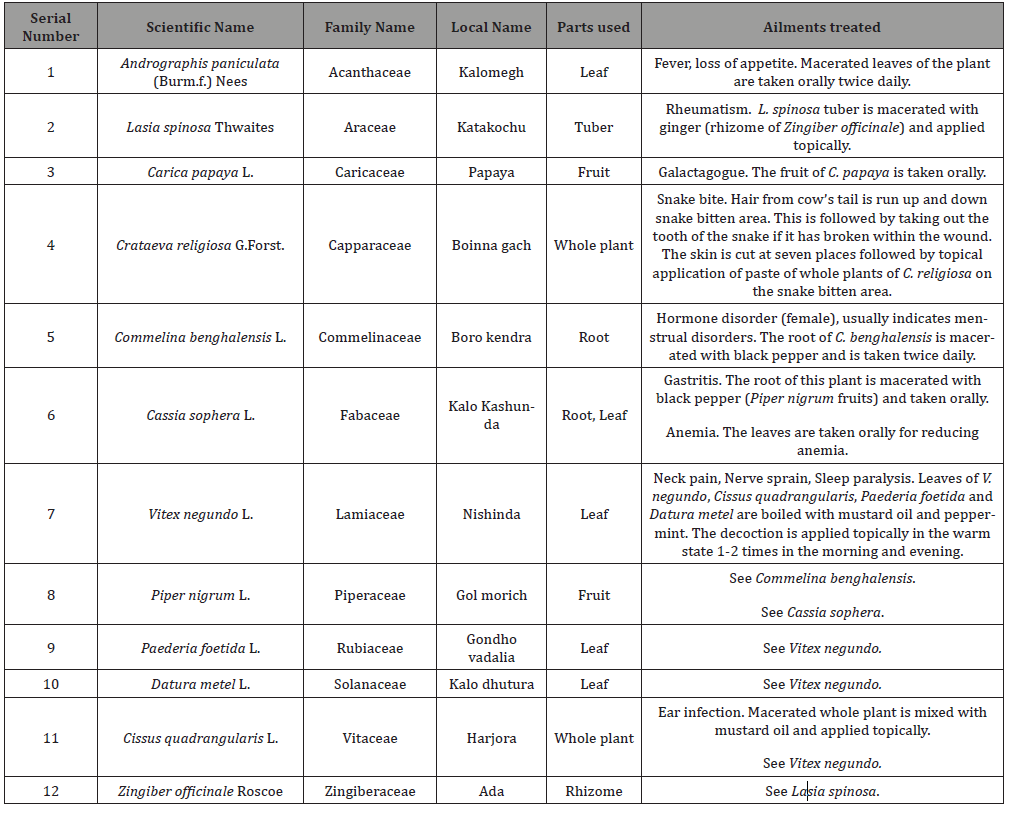

The FMP used a total of twelve plants in monoherbal and polyherbal formulations to treat fever, loss of appetite, rheumatism, snake bite, female hormonal disorders, gastritis, anemia, neck pain, nerve sprain, sleep paralysis, ear infection and as a galactagogue. The results are shown in Table 1. Female hormonal disorders are taken in rural Bangladesh to mean either infertility or menstrual problems. Nerve sprain is pain in any portion of the body due to sudden twisting of that body part; in most cases, it indicates neck pain caused from not using proper support for the head and neck during sleeping. Sleep paralysis is inability to speak or move after waking up or while falling asleep; it can be temporary or last longer if it happens from extreme fear, which in rural areas happens when a person imagines to have seen something evil from the spirit world in dream or while waking up suddenly during sleeping. Andrographis paniculata was used by the FMP to treat fever and loss of appetite. The latter can be an individual problem or arising out from fever. The plant contains the anti-pyretic compound, andrographolide, which has been shown to reduce fever in Brewer’s yeast induced pyrexia in rats [38]. Improvement of appetite has been seen with infective hepatitis patients following treatment with the plant [39]. Lasia spinosa and Zingiber officinale have been reported to possess analgesic and anti-inflammatory properties [40,41]; the reports validate the use of the FMP of these two plants to treat rheumatism. The leaves of Carica papaya have lactagogue effect [42]; the FMP used the fruits of the plant (Table 1).

Table 1: Medicinal plants and formulations of the FMP from Kushtia district, Bangladesh.

Crataeva religiosa has medicinal uses in traditional medicinal system of India to treat snake bite [43]. Commelina benghalensis is used to treat infertility in women in many parts of tropical Asia [44]. The fruits of black pepper can be beneficial during gastritis; the fruits also stimulate digestive enzymes, which in turn can lead to amelioration of anemia by stimulating more food consumption; the active ingredient is known to be piperine [45]. Mature fresh leaves of Vitex negundo have analgesic and anti-inflammatory properties [46], so the leaves can be used for neck pain or sprain. The same applies to Cissus quadrangularis, Paederia foetida and Datura metel [47-49]. Thus the three plants in combination can be useful against neck pain and nerve sprain. However, their effectiveness against sleep paralysis needs to be scientifically determined. The analgesic and anti-inflammatory properties of C. quadrangularis can also make it an effective plant to be used against any pain and inflammation associated with ear infection. Overall, it can be seen from published scientific reports that the various plants used by the FMP are more or less scientifically validated in their therapeutic uses based on their reported pharmacological activities and phytochemical contents. FMPs and FM cannot then be describes as mere ‘quackery’, although there may be isolated cases of fraudulent practices.

Conclusion

Our findings suggest that the phytotherapeutic methods of the present FMP were quite consistent with available scientific reports on the pharmacological properties and phytochemical contents of the plants used by the FMP. As such, folk medicine can form the basis for herbal cures and the plants used in folk medicine can prove to be valuable sources of new drugs.

Acknowledgement

The authors are grateful to the FMP for providing information on his phytotherapeutic practices.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

References

- Traditional Medicine in Kingdom of Thailand (2019) The Integration of Thai Traditional Medicine in the National Health Care System of Thailand pp. 97-120.

- Majaz AQ, Khurshid IM (2016) Herbal medicine: A comprehensive review. Int J Pharm Res 8(2): 1-5.

- Kaszycka KA (2017) The Australopithecines: An extinct group of human ancestors: My scientific interest in South Africa. Werkwinkel 12(1): 7-17.

- Newton P (1991) The use of medicinal plants by primates: A missing link? Trends Ecol Evol 6(9): 297-299.

- Shakya AK (2016) Medicinal plants: Future source of new drugs. Int J Herb Med 4(4): 59-64.

- Rahmatullah M, Ferdausi D, Mollik MAH, Jahan R, Chowdhury MH, et al. (2010) A Survey of Medicinal Plants used by Kavirajes of Chalna area, Khulna District, Bangladesh. Afr J Tradit Complement Alternat Med 7(2): 91-97.

- Rahmatullah M, Khatun MA, Morshed N, Neogi PK, Khan SUA, et al. (2010) A randomized survey of medicinal plants used by folk medicinal healers of Sylhet Division, Bangladesh. Adv Nat Appl Sci 4(1): 52-62.

- Rahmatullah M, Kabir AABT, Rahman MM, Hossan MS, Khatun Z, et al. 2010 Ethnomedicinal practices among a minority group of Christians residing in Mirzapur village of Dinajpur District, Bangladesh. Adv Nat Appl Sci 4(1): 45-51.

- Rahmatullah M, Momen MA, Rahman MM, Nasrin D, Hossain MS, et al. (2010) A randomized survey of medicinal plants used by folk medicinal practitioners in Daudkandi sub-district of Comilla district, Bangladesh. Adv Nat Appl Sci 4(2): 99-104.

- Rahmatullah M, Mollik MAH, Ahmed MN, Bhuiyan MZA, Hossain MM, et al. (2010) A survey of medicinal plants used by folk medicinal practitioners in two villages of Tangail district, Bangladesh. Am-Eur J Sustain Agric 4(3): 357-362.

- Rahmatullah M, Mollik MAH, Islam MK, Islam MR, Jahan FI, et al. (2010) A survey of medicinal and functional food plants used by the folk medicinal practitioners of three villages in Sreepur Upazilla, Magura district, Bangladesh. Am-Eur J Sustain Agric 4(3): 363-373.

- Rahmatullah M, Jahan R, Khatun MA, Jahan FI, Azad AK, et al. (2010) A pharmacological evaluation of medicinal plants used by folk medicinal practitioners of Station Purbo Para Village of Jamalpur Sadar Upazila in Jamalpur district, Bangladesh. Am-Eur J Sustain Agric 4(2): 170-195.

- Rahmatullah M, Ishika T, Rahman M, Swarna A, Khan T, et al. (2011) Plants prescribed for both preventive and therapeutic purposes by the traditional healers of the Bede community residing by the Turag River, Dhaka district. Am-Eur J Sustain Agric 5(3): 325-331.

- Rahmatullah M, Azam MNK, Rahman MM, Seraj S, Mahal MJ, et al. (2011) A survey of medicinal plants used by Garo and non-Garo traditional medicinal practitioners in two villages of Tangail district, Bangladesh. Am-Eur J Sustain Agric 5(3): 350-357.

- Rahmatullah M, Biswas KR (2012) Traditional medicinal practices of a Sardar healer of the Sardar (Dhangor) community of Bangladesh. J Altern Complement Med 18(1): 10-19.

- Rahmatullah M, Hasan A, Parvin W, Moniruzzaman M, Khatun A, et al. (2012) Medicinal plants and formulations used by the Soren clan of the Santal tribe in Rajshahi district, Bangladesh for treatment of various ailments. Afr J Tradit Complement Alternat Med 9(3): 350-359.

- Rahmatullah M, Khatun Z, Hasan A, Parvin W, Moniruzzaman M, et al. (2012) Survey and scientific evaluation of medicinal plants used by the Pahan and Teli tribal communities of Natore district, Bangladesh. Afr J Tradit Complement Alternat Med 9(3): 366-373.

- Rahmatullah M, Azam MNK, Khatun Z, Seraj S, Islam F, et al. (2012) Medicinal plants used for treatment of diabetes by the Marakh sect of the Garo tribe living in Mymensingh district, Bangladesh. Afr J Tradit Complement Alternat Med 9(3): 380-385.

- Rahmatullah M, Khatun Z, Barua D, Alam MU, Jahan S, et al. (2013) Medicinal plants used by traditional practitioners of the Kole and Rai tribes of Bangladesh. J Altern Complement Med 19(6): 483-491.

- Rahmatullah M, Pk SR, Al-Imran M, Jahan R (2013) The Khasia tribe of Sylhet district, Bangladesh, and their fast-disappearing knowledge of medicinal plants. J Altern Complement Med 19(7): 599-606.

- Akter S, Nipu AH, Chyti HN, Das PR, Islam MT, et al. (2014) Ethnomedicinal plants of the Shing tribe of Moulvibazar district, Bangladesh. World J Pharm Pharmaceut Sci 3(10): 1529-1537.

- Azad AK, Mahmud MR, Parvin A, Chakrabortty A, Akter F, et al. (2014) Medicinal plants of a Santal tribal healer in Dinajpur district, Bangladesh. World J Pharm Pharmaceut Sci 3(10): 1597-1606.

- Azad AK, Mahmud MR, Parvin A, Chakrabortty A, Akter F, et al. (2014) Ethnomedicinal surveys in two Mouzas of Kurigram district, Bangladesh. World J Pharm Pharmaceut Sci 3(10): 1607-1620.

- Kamal Z, Bairage JJ, Moniruzzaman, Das PR, Islam MT, et al. (2014) Ethnomedicinal practices of a folk medicinal practitioner in Pabna district, Bangladesh. World J Pharm Pharmaceut Sci 3(12): 73-85.

- Anzumi H, Rahman S, Islam MA, Rahmatullah M (2014) Uncommon medicinal plant formulations used by a folk medicinal practitioner in Naogaon district, Bangladesh. World J Pharm Pharmaceut Sci 3(12): 176-188.

- Esha RT, Chowdhury MR, Adhikary S, Haque KMA, Acharjee M, et al. (2012) Medicinal plants used by tribal medicinal practitioners of three clans of the Chakma tribe residing in Rangamati district, Bangladesh. Am Eur J Sustain Agric 6(2): 74-84.

- Malek I, Miah MR, Khan MF, Awal RBF, Nahar N, et al. (2014) Medicinal plants of two practitioners in two Marma tribal communities of Khagrachhari district, Bangladesh. Am Eur J Sustain Agric 8(5): 78-85.

- Shakera J, Mandal R, Akter T, Nahar N, Rahmatullah M (2019) Folk medicine in Bangladesh: Healing with plants by a practitioner in Kushtia district. Arch Pharm Pharmacol Res 1(5).

- Rahmatullah M, Jannat K, Nahar N, Al-Mahamud R, Jahan R, et al. (2019) Tribal medicinal plants: documentation of medicinal plants used by a Mogh tribal healer in Bandarban district, Bangladesh. Arch Pharm Pharmacol Res 1(5).

- Shova NA, Islam M, Rahmatullah M (2019) Phytotherapeutic practices of a female folk medicinal practitioner in Cumilla district, Bangladesh. J Med Plants Stud 7(4): 1-5.

- Jannat K, Al Mahamud R, Jahan R, Hamid A, Rahmatullah M (2019) Phyto and zootherapeutic practices of a Marma tribal healer in Bandarban district, Bangladesh. Int J Appl Res Med Plants 2(1): 9.

- Shandhi MM, Khatun T, Mondol N, Patwary SA, Jannat K, et al. (2019) Tying or hanging of plants to body to cure diseases: an esoteric method of treatment. J Med Plants Stud 7(2): 131-133.

- Mondol N, Patwary SA, Shandhi MM, Khatun T, Jannat K, et al. (2019) A study of folk medicinal practices in Debashur village, Gopalganj district, Bangladesh. World J Pharm Res 8(5): 589-598.

- Jannat K, Shova NA, Islam MMM, Jahan R, Rahmatullah M (2019) Herbal formulations for jaundice treatment in Jamalpur district, Bangladesh. J Med Plants Stud 7(2): 99-102.

- Hosen MS, Rahmatullah M (2019) Simple phytotherapeutic practices of a Tripura tribal medicinal practitioner in Bandarban district, Bangladesh. J Med Plants Stud 7(1): 93-95.

- Martin GJ (1995) In: Ethnobotany: a ‘People and Plants’ Conservation Manual, Chapman and Hall, London pp. 268.

- Maundu P (1995) Methodology for collecting and sharing indigenous knowledge: a case study. Indigenous Knowledge and Development Monitor 3(2): 3-5.

- Madav S, Tripathi HC, Tandon, Mishra SK (1995) Analgesic, antipyretic and antiulcerogenic effects of andrographolide. Ind J Pharm Sci 57(3): 121-125.

- Bharati BD, Sharma PK, Kumar N, Dudhe R, Bansal V (2011) Pharmacological activity of Andrographis paniculata: A brief review. Pharmacologyonline 2: 1-10.

- Goshwami D, Rahman MM, Muhit MA, Islam MS (2013) Antinociceptive, anti-inflammatory and antipyretic activities of methanolic extract of Lasia spinosa leaves. Int J Pharm Chem Sci 2(1): 118-122.

- Raji Y, Udoh US, Oluwadara OO, Akinsomisoye OS, Awobajo O, et al (2002) Anti-inflammatory and analgesic properties of the rhizome extract of Zingiber officinale. Afr J Biomed Res 5: 121-124.

- Pratiwi TE, Suwondo A, Mardiyono (2018) Exclusive breastfeeding improvement program using Carica papaya leaf extract on the levels of prolactin hormones. Int J Sci Res 7(9): 548-551.

- Patil UH, Gaikwad DK (2011) Medicinal profile of a sacred drug in Ayurveda: Crataeva religiosa A review. J Pharm Sci & Res 3(1): 923-929.

- Orni PR, Shetu HJ, Khan T, Rashed SSB, Dash PR (2018) A comprehensive review on Commelina benghalensis L. (Commelinaceae). Int J Pharmacogn 5(10): 637-645.

- Srinivasan K (2009) Black pepper (Piper nigrum) and its bioactive compound, piperine. Molecular Targets and Therapeutic Uses of Spices, pp. 25-64.

- Dharmasiri MG, Jayakody JRAC, Galhena G, Liyanage SSP, Ratnasooriya WD (2003) Anti-inflammatory and analgesic activities of mature fresh leaves of Vitex negundo. J Ethnopharmacol 87(2-3): 199-206.

- Vijay P, Vijayvergia R (2010) Analgesic, anti-inflammatory and antipyretic activity of Cissus quadrangularis. J Pharm Sci Technol 2(1): 111-118.

- Das S, Bordoloi PK, Saikia P, Kanodia L (2012) The analgesic and acute anti-inflammatory effect of the ethanolic extract of the leaves of Paederia foetida (EEPF) on experimental animal models. Bangladesh J Med Sci 11(3): 206-211.

- Wannang NN, Ndukwe HC, Nnabuife C (2009) Evaluation of the analgesic properties of the Datura metel seeds aqueous extract. J Med Plants Res 3(4): 192-195.

-

Mohammed Rahmatullah, Jakera Shakera, Rony Mandal, Nasrin Akter Shova, Nargis Ara, et al. Do Folk Medicinal Practices of Bangladesh Have any Scientific Value? an Appraisal of Phytotherapeutic Practices of a Rural Folk Medicinal Practitioner. Arch Phar & Pharmacol Res. 2(1): 2019. APPR.MS.ID.000529.

-

Folk medicine, Scientific validation, Phytotherapy, Kushtia, Bangladesh, Folk medicinal practitioners, Ailments, Radiocarbon, Babylon, Australopithecines, Ethnomedicine, Antibiotic-resistant, microorganisms, Quackery, Therapeutic.

-

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.