Research Article

Research Article

Using Cellphone While Driving Among Saudi Drivers in Saudi Arabia, Cross Section Study 2018

Fahad I Alamri1, Maria Alamr2, Afra Bukhari2, Randah Al alweet2, Alanoud Nugali2 and Samar A Amer3*

1Department of Family Medicine, Dg of Health Promotion and Health Education, Ministry of Health, Saudi Arabia.

2Department of epidemiology, Health and Rehabilitation College, Princess Noura Bint Abdulrahman University, Saudi Arabia.

3Department of public health and community medicine and fellowship of Royal college at family medicine, Saudi Arabia.

Samar A Amer, Department of public health and community medicine and fellowship of Royal college at family medicine, Saudi Arabia.

Received Date: June 09, 2020; Published Date: July 14, 2020

Abstract

Background: Recently, the use of cell phone has increased among people nevertheless use it while driving lead to driver distraction which increases the risk of accidents and it is considered as a main cause of deaths in Kingdom of Saudi Arabia (KSA).

The aim: To measure the level of knowledge, the practice and the risk of using cell phone while driving and its’ related hazards in KSA, in order to decrease the prevalence of its use while driving.

Method: A cross-sectional study targeting 1320 randomly selected Saudi drivers, stratified to present the main 5 different regions (404 center, 386 west, 212 east, 232 souths, and 86 north), during October 2017-Jan year 2018. The data collected through online well-structured questionnaire and analyzed using the suitable tests.

Results: 1003(75.9%) of participants using cellphone recurrent while driving, 1076(81.5%) for calling, because 44.3% addicted to its use,85.1% by hands,90% when alone. 59.1% of drivers don’t use the Cellphone Holder or Bluetooth due to unavailability.82.8% had an accident, and 86% exposed to danger .97.9% had good knowledge only 12.1% had good practice, there was a significant association between using cell phone while driving and risk of accidents (p<0.05).

Conclusion: The central region had a highest prevalence of using cell phone while driving, most of the drivers have a good knowledge but they still using cell phone while driving in a bad practice.

Keywords: Cell phone use; Driving; Accident, KSA

Introduction

Road Injuries are the main cause of deaths in Kingdom of Saudi Arabia (KSA) [1]. However, driving cars is the most important transportation in developed countries, but most of the drivers are not fully aware of the driving rules that probability of occurrence hazards [2]. In recent years the importance of mobile phones has increased among people and they can use it in both positive and negative way [3], such as in Jeddah they estimated the number of using the cell phone while driving by 98.2% of them [4].

Moreover, the prevalence of using cell phone while driving was different between countries such as United States (US) 69% [5] and United Arab Emirates (UAE) 80% [6] are showed higher prevalence than the United Kingdom (UK) 21% [5] and Australia 39% [7]. In fact, using cell phone while driving lead to driver distraction which defined as ‘’the diversion of attention from activities critical for safe driving towards a competing activity, it is a behavior that jeopardizes the safety of drivers, passengers, and non-occupants alike’’ [8]. The distraction of using cell phone while driving can distract drivers’ eyes (visually) and minds to be attention to the road (cognitively) and their hands on the steering wheel (physically) [9]. Distraction crashes killed 3,092 people, 408 (13%) of them at least one driver was using cell phone when the crashes occurred [8] As well as 78% of the accidents in KSA related to using cell phone while driving [10]. A study showed, the risk of accident dramatically increasing with using cell phone while driving, (72%) of drivers believe that very likely to have a crash caused by texting/browsing cell phone, while (41%) very unlikely of a voice call (handheld) [7]. Moreover, Study show that uses cell phone while driving is similar dangerous with driving in the drunk situation at the legal limit [11].

Most governments develop their laws of using cell phone while driving, for instance in KSA, Ministry of Interior apply fines not less than 150 Saudi Riyal(S.R.) and not more than 300S.R. for using cell phone while driving [12] and in the UK the penalty of using handheld phone is 200£ while driving car and 2,500£ while driving lorry or bus [13]. As a global rank road traffic accident become the 11th leading cause of death [14]. Moreover, road traffic accident gave a higher rate of mortality in all Gulf countries [15,16]. While in KSA road injuries are the main cause leading to death [1]. Lately using cell phone while driving has become more common among drivers and it caused to injuries, disability, and accident.

Using cell phone while driving

Due to technological changes, the importance of cell phones services become more and more significant throughout the world. The reasons of that are what these devices have to software and features such as (social media, GPS, games, radio, internet and downloading, et al) that makes the daily life easier [17].

According to Sanbonmatsu D, Strayer D, et al. (2015) [18], the study conducted in Salt Lake City, Utah with 77 undergraduate participants to examine the impact of multitasking on performance monitoring and assessment showed there is a significant association between using cell phone while driving and the more serious errors of driving (p = .008). Also, people who use cell phone while driving is less aware than people who did not use it. These results indicate weak awareness among drivers about traffic safety [18].

A cross-sectional survey of 695 respondents was aimed to determine the prevalence of seat belt use and distracted driving behaviors among health-care providers in Saudi Arabia and its comparison with non-health-care providers in 2017. According to Jawadi H., et al Study showed most of the drivers using cell phone while driving but the highest rate was among who answer the cell phone while driving (98.5%).

Also, most of the drivers texting a message while driving (74.3%) but the accident that caused by text a messaging was only (28.7%) [19]. Open-ended interviews study with 228 sample conducted in U.S by Bergmark R, Gliklich E, Guo R, Gliklich R. [20] to describes the development and preliminary evaluation of the Distracted Driving Survey (DDS) and score in 2016. As we mentioned before, most of the drivers prefer to use cell phone to text a message while driving and study showed only 12.7% read the message while driving with any speed, 15.6% lowering them speed and 10.1% when stopped [2].

Recently, cell phone has become a necessity of life and has spread among the world as much as there are advantages and disadvantages to using cell phone according to Billieux J, Maurage P, Lopez Fernandez O, Kuss D, Griffiths M [21] study conducted in 2015 show Enhancement of health education in terms of physical fitness, healthy food, and improved behavior was from advantage of using cell phone but using phone while driving, addiction to using cell phone and health damages were disadvantages of using phone [22]. In 2015 a qualitative study was done in Pennsylvania by McDonald C, and Sommers M, to describe teen drivers’ perceptions of cell phone use while driving in order to inform future interventions to reduce risky driving among 30 drivers, Study showed most adolescents know the risk and distracting of using mobile phone while driving but there still using for text message, calling and social applications while driving [23].

Prevalence of using cellphone while driving among drivers

The prevalence of using a cellphone while driving is different between countries [5]. However, most countries around the world their prevalence is above 50% while there are countries with lower prevalence but not one of the Gulf countries [4,6,20,24]. A crosssectional study conducted by Jawadi, A. et al. in 2017 [19]. The title of the study was (Seat belt usage and distracted driving behaviors in Saudi Arabia: Health-care providers versus Nonhealth-care providers). The sample size of the study was 695 Saudi respondents who live in Saudi Arabia, aged 18 years and above, 51.2% of them were health-care providers and the rest were Nonhealth-care providers. Data were collecting out of online questionnaire and distributed through the emails of Saudi health-care providers in Saudi Arabia and social media using a snowball. One of the results showed the prevalence of using a cell phone while driving and it was 99.1% health-care providers and 89.8% of Nonhealthcare providers (total prevalence =95.9%) [20]. In another hand Trespalacios, O. King, M. Haque, M. and Washington, s. conducted a cross-sectional study in Queensland (2017). The study aimed to investigates characteristics of usage, risk factors, compensatory strategies in use and characteristics of high-frequency offenders of mobile phone use while driving. The study conducted an anonymous online questionnaire distributed across social media, local press releases, and electronic mail through Queensland University of Technology mailing lists.

Not only-but also public face-to-face dissemination. The sample size was 484 drivers 49.8% were aged 17-25 years and 50.2% were aged 26–65 years, 65.1%of them were women. The results showed that 49% used a cell phone while driving [7]. Moreover, at 2016 a cross-sectional study was done by Ahamed H, and Hafian, M in Saudi Arabia, Jeddah with 882 sample size. The aim of the study was to investigate the effects of using a cell phone while driving. The sample included men drivers aged above 17 participants. The instrument of this study developed a 34-item closed-format questionnaire. As a result, the prevalence of the study was 98.2% of drivers use their cell phones while driving [4]. At 2015 Rasool, F. et al. [24] conducted a cross-sectional study aimed to raise awareness about road traffic accidents and their causes and consequences among medical students in Arabian Gulf University (AGU) in Bahrain.

The sample size was 200 students with Bahraini or non- Bahraini, aged between 20-24 years. Data instrument was a structured questionnaire and designed to be self-filled by the participants. The prevalence of using a cell phone while driving (49%) showed in a part of the results [25].

An observational study conducted in Texas, US (2015) by Wilkinson, M. Brown, A. Moussa, A. Day, R. the study aimed to assess the 3-year prevalence of cell phone use (CPU) of drivers and characteristics associated with its use in six cities across Texas, from 2011–2013. CPU and driver characteristics of 1280 motor vehicles observed at major intersections in Dallas, Austin, San Antonio, El Paso, and Brownsville at respective University of Texas medical and academic campuses. The main result showed an overall prevalence of CPU, which was 18.7% [26].

Another study evaluates relevant factors related to causes of Road Traffic Accidents, RTAs among drivers in Abu Dhabi, UAE, 2014. Quantitative data method used through questionnaire survey as it is developed and piloted in the UK and UAE with 600 drivers as a sample size, aged between 18 and less to 65 years, 49% of the questionnaires returned. The prevalence of using a cell phone while driving was 80% in both male and female [6]. In addition, Al-Rees, H. et al. have done a cross-sectional study conducted in Oman, 2013. The study aimed to investigate driving behavior as indexed in the Driving Behavior Questionnaire (DBQ). A sample of 1003 participants was token from Omani university, 632 of them were students and 371 were staffs aged with a range of 17-58 years. The instrument of this study is a standard questionnaire that called DBQ questionnaire. The results showed that 92% of the drivers are using a cell phone while driving [24].

Demographic factors associated with using cell phone while driving

A study was done in Kingdom of Saudi Arabia in 2017 by Ahamed and Hafian to investigate the effects of mobile phone usage while driving. The sample size was 882 drivers aged over 17 years, they surveyed by a 34 -item closed-format questionnaire to gather information on their mobile phone use while driving as well as their risk perception. The survey covers eight variables representing demographic characteristics of the participants; nationality of the participant, marital status, education, work status, age, driving experience, the time participant got a smart mobile phone and conversation with passengers. A part of result in this study show there was statistically significant differences in the use of mobile phone while driving according to their nationality (P=0.03). The frequency of using mobile phone while driving is higher for Saudi- driver than non- Saudi- driver. Also, there were statistically significant differences according to marital status (P=0.04) and work status (P = 0.04). However, there were no statistically significant differences in the use mobile phone while driving according to their age, education level and driving experience [4].

Moreover, a study has done by Rudisill and Zhu in 2017, examined whether universal hand-held calling while driving bans were associated with lower road-side observed hand-held cell phone conversations across drivers of different ages (16≥60 years), sexes, races, ruralities, and regions conducted in US. The main data source was the 2008–2013 National Occupant Protection Use Survey (NOPUS). In this analysis, 263,673 drivers are included. The result shows that drivers aged between 16–24 years are talked on hand-held devices more than other age groups regardless of handheld ban existence and sub-group differences were seen in regards to drivers’ sex females talked on hand-held phones more than males irrespective of whether a hand-held ban was in existence. In case of drivers’ race, no sub-group differences were noted (p = 0.30) [27].

A cross-sectional study was conducted by V Kumar, Dewan and D Kumar [27] among 848 school going adolescents (15-19 years) over one year from 2014 to 2015 in India with an aim to assess the health risk behavior of rural and urban male adolescents concerning injuries, violence and sexuality. The participants were selected from government and private schools by using multistage simple random sampling technique. Data were collected by using self-administered 2011 youth risk behaviour survey (YRBS). In the results, almost quarter of both rural and urban adolescents were report using mobile phone while driving in at least up to 10 days during the past 30 days 22%. (statically significant (p<0.05). The study concluded that adolescents frequently reported high risk behaviour regardless of place of residence and type of school [28].

In addition, Hammoudi, Karani and Littlewood conducted study in 2014 aimed to evaluate relevant factors related to causes of Road Traffic Accidents, RTAs, among drivers in Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates, UAE. The participant in this steady was 600 drivers in Abu Dhabi aged between 18 and less to 65 years and the received a questionnaire survey that designed to obtain information regarding their behaviors and attitudes and it was piloted in the UK and UAE. The study shows the using mobile phone while driving is statistically significant related with nationalities (p=0.04). However, there was no statistically significant relationship between using mobile phone while driving and other demographic factors like: gender, age, monthly income or education [6].

Knowledge, practice and attitude toward using cell phone while driving

Trespalacios, O King, M Haque, M and Washington s conducted a cross-sectional study in Queensland (2017). The study aimed to self-reported behaviour and attitudinal characteristics of mobile phone distracted driver. The study conducted an anonymous online questionnaire distributed by social media and electronic mail through Queensland University of technology students. also, public face-to-face dissemination. the sample size was 484 drivers 49.8% were aged 17–25 years and 50.2% were aged 26–65 years, 65.1%of them were women. The result shows that 45% of the participants answering a ringing phone compared to 28% of participants who use the handheld phone. The correlation between answering a ringing phone and using handheld was statistically significant (p < 0.05, n = 117). On other hands, 34% of participant texted or browsed than 39% looked at the phone more than 2 seconds. The association between these two activities were significant (p <0.001, n = 109). However, 12% of participants need more conviction to believe talking is dangerous compared to 4% of the participants need a lot of persuasive to believe the danger of texting and browsing. With observance to the differences in driving behavior, 79% of the participant is likely to lower their driving speed, 70% increase the distance from the car in front and 44% scan the check the road while texting or browsing. Furthermore, 33% were peripheral to increase their control over the steering wheel while talking. Although regarding self-regulatory behavior, 9% of respondents mentioned that they reminded the caller that they were driving or shortened the conversation [7].

A cross-sectional study conducted in the United States (2017) by Rudisill TM, and Zhu M [26] the study aimed to investigate the association between hand-held CPWD laws and roadside observed hand-held cell phone conversations across driver sub-groups and regions. the percentage of drivers who were talking on a hand-held phone was 5.1%. therefore, over 72% of the drivers the hand-held was not present. Also, 85% of respondents were wearing seat belts. The younger drivers, female, African American, and from Southern states compared to those not engaging in cell phone conversations [27].

Moreover, at 2016 a cohort study was done by Bergmark RW, Gliklich E, Guo R and Gliklich RE [20] in Boston with 228 sample sizes. The aim of the study was to develop a reliable self-reported survey for assessing levels of cell phone related distracted driving associated with viewing and typing activities and to validate it in a higher risk population of drivers age 24 years or younger. As a result, most of the respondents wrote text messages never or rarely, while 16 % said they write text messages some of the times they drive and 7.4 % said they write text messages most or every time they drive. Although they were asked about their speed when they write text message, 9.7 said they write text messages at any speed in addition 24.1% said that they write text messages in low speed or in stop and go traffic. Furthermore, reading text messages was more common, 71.5% of respondents said they read text messages while driving (29% rarely, 27.2% sometimes, 13.2 most of the time, and 2.2 % every time they drove. Compared to writing texts, 12.7 % read text messages at any speed, 15.6 % at low speeds and 10.1% in stop and go traffic. Reading and writing an email and browsing social media were less common. 74.6 % of respondents have used maps on a phone. About their knowledge or thinking, 36%.4 of participants think that texting while driving is never safe, 27.6% said rarely, 20.2% said sometimes, 8.8% said most of the time and 7.0% said it always safe [21].

Another study conducted by Zhou, R., Yu, M. and Wang, X. in China (2016). The study aimed to assess drivers’ compensatory beliefs and address the frequency of engagement of different selfregulatory actions for mobile calls or messaging and to examine the effects of basic demographic measures on drivers. Also, to address whether mobile phone usage while driving can be predicted by driver’s compensatory beliefs. The result shows that 17.14% of participants sending text messages, 23.57% making calls, 29.29% reading text messages and 40% answering calls (p < 0.05). however, 90% of respondents who answering call while drive said they reminded the caller that they were driving or shortened the conversation. With regard to driving behaviors, the percent of drivers who slow down or increase the distance when the use cell phone was more than 80%, drivers reported less frequency in changing lanes was 77% and who pulled over more frequently was 60% with p-value (p < 0.05) [29].

According to Adolescent Cellphone Use While Driving: An Overview of the Literature and Promising Future Directions for Prevention study was done by Delgado M, Wanner K and McDonald C (2016) [29]. The study aimed to provide an overview of the incidence, crash risk, risk factors for engagement, and the effectiveness of current mitigation strategies. The results show that 97% of adolescents know texting and driving are dangerous. however, they still use cell phone in talking, texting and social media app while driving [30]. In another hand Parr M, Ross L, McManus B, Bishop H et. [30] Conducted self-reported personality factors and the Questionnaire Assessing Distracted Driving in the United States (2013-2014). The study aimed to determine the impact of personality on distracted driving behaviors. Teens reported significantly more instances of interacting with the phone (t (50.61) = 4.25, p < .0001) and more instances of texting while driving compared to older adults (t (46.175) =3.87, p = .0003). No significant differences were found between teens and older adults on the number of instances of talking on the phone while driving [31].

Risk of using cell phone while driving

Risk of an accident

An observational study aimed to examine in a naturalistic driving setting the dose-response relationship between cell phone usage while driving and risk of a crash or near crash. One hundred and five (105) participants in UK were observed every day for one year, each month 4 trips were chosen as a random sample to classify driver behavior and every 3 months they work to find out the relationship of using phone while driving and overall crash and near-crash rates for each period. this survey published at 2015 with a result of the risk of a near-crash/crash was 17% higher when the drivers use cell phone this proportion was more likely due to the use of the phone in answering and calling, which nearly triples risk (relative risk = 2.84) [32].

Oviedo-Trespalacios, O., King, M., Haque, M. and Washington, S. at 2017 conducted a cross-sectional study with the title (Risk factors of mobile phone use while driving in Queensland: Prevalence, attitudes, crash risk perception, and task-management strategies). The sample size was 484 drivers aged 17 – 65 years, 34.9% were males and 65.1% females. Data instrument used in this study was an online questionnaire disseminated by using social media (Twitter, Facebook, and blogs), local press releases, and electronic mail through Queensland University of Technology mailing lists and public face-to-face dissemination. The results showed that around 72% of the participants reported high-perceived crash risk for mobile phone usage for browsing/texting with a significance of p-value < 0.001 [7].

Health problems

A systematic review study of 29 papers in 2014 done by Cazzulino, Burke, Muller, Arbogast, & Upperman [32] aimed to determine factors that influence young drivers to engage in (CPWD; defined here as talking on the phone only) and texting while driving (TextWD) suggest a basis for prevention campaigns and strategies that can effectively prevent current and future generations from using cell phones while driving. The result showed there is a relationship between using cell phone while driving and psychological factors in young drivers [33].

In 2017 a qualitative study with 123 injured drivers by Brubacher J, Chan H, Purssell E, Tuyp B, Ting D, Mehrnoush V, to determine the prevalence of driver-related risk factors and subsequent outcome in drivers involved in minor crashes. The result showed, most of the drivers during 6 months they still suffer from health problems, were 53.3% did not recover completely from their health and 46.7% had not returned to their previous activities. On the other hand, were 16.7% using a cell phone while driving and unfortunately, drivers still continue on risk after being injured [34]. According to Martin J, Kauer SD, Sanci L, in 2016 a cross-sectional study in Australia aimed to examine the type of road risks and associated behaviors in young people attending general practice among 901 patients showed, most of the young engaging at least in one road risks or more. Moreover, there is no significant assocciation between road risks and people with the risk of mental health p-value (0.260) [35].

Strategies and policies of using phone while driving

Traffic violation of using cell phone while driving have a different laws and regulations between countries, which is study shows the strict laws can affect to reduce the rate of using phone while driving. There are some drivers still using phone despite governments efforts to limit of using phone while driving [36]. In KSA Fines not less than (S.R.150) and not more than (S.R.300) for who using cell phone while driving (11). While in the United Arab Emirate Using phones while driving or any other distractions will be attracted AED 400 fine and four black points [37]. In Bahrain, a driver pays a fine of 50 BD when making or receiving a phone call by hand held [38]. Also, in Jordan, use phone in handheld while driving is a traffic violation (15 JOD) [39]. In United Kingdom it’s illegal to using phone while driving, you will breaking the low if you use it when you are stopped at traffic lights, when you are queuing in traffic, to make or receive calls, to send or receive picture and text messages and to access the internet.

If you are caught using a hand-held mobile phone or similar device while

1) Driving or riding, you’ll get an automatic fixed penalty notice - three penalty points and a fine of £60.

2) If your case goes to court, you may face disqualification on top of a maximum fine of £1,000. Drivers of buses and goods vehicles face a maximum fine of £2,500.

3) If you reach six or more points within two years of passing your test, your licence will be taken off you. You’ll need to re-sit your driving test to get your licence back [13].

Rational

In KSA road injuries are the first cause of death with 9% [1]. Drivers using cell phones are approximately 4 times more likely to be in accidents than drivers that are not using cell phone, [39] is considered on an issue because of 78% of accidents caused by using phone while driving [11]. Moreover, accidents cost 3% in most countries of their gross domestic product. As well as it can affect the personal level, for instance in health it can lead to back neck or brain injuries or/and disability [39]. Measure the knowledge, attitude, and practice among drivers can help us to find out the solution to decrease the prevalence of using cell phone while driving.

Aim

To decrease the prevalence of using cell phone while driving and its’ related hazards in KSA through the following objectives among Saudi male drivers:

I. Determine the prevalence of using cell phone while driving.

II. Assessing the knowledge, attitude and practice when using cell phone while driving among Saudi.

III. Identify the relationship between using cell phone while driving and demographic variable among Saudis.

IV. Identify the relationship between using cell phone while driving and risk of accident among Saudi.

Methodology

A cross-sectional study targeting all Saudi male drivers, which conducted during Oct-Jan year 2017 in KSA. Study includes all Saudi men drivers aged between 17-60 years and excludes non-Saudi drivers, more than 60 years old and driver with mental disease.

Sampling Methods

A cluster sampling method used. The sample distributed into 5 different regions in KSA: South- East- West- North and the center, then take the big city of each region Riyadh city from the Center, Mecca from the West, Tabuk from the North, Aseer from the South and East region. After that, purposive sampling was used because the access to the participant it was difficult. The sample was conducted from hospitals, universities, crowded streets and companies.

Sample size

The sample size was 660 participants, calculated using Open Epi website, with a population of 6,026,479 Saudi men aged between 17-59 in KSA, with 95% confidence interval, and using a prevalence 78% of accidents caused by using a cell phone while driving [11]. The 660 participants doubled to be 1,320 participants in case to increase the power of the study, increase sample size and to achieve the roles of the cluster method. then proportionally divided into 5 different regions, 404 participants in the center, 386 in the west, 212 in the east, 232 in the south, while 86 in the north.

Data collection instrument

Collected the data was by using online survey questionnaire in the Arabic language by Google Forms website and the participants were received the link by the data collector. The questionnaire was constructed with a total number of 16 question and classified into 4 parts. The first part includes questions on demographic information, the second part contains questions measure the knowledge of using cell phone while driving, third part contains questions to measure the practice of using cell phone while driving, and the last part includes questions for risk of using cell phone while driving the study. Before the data collected, a pilot study among 10 drivers at Ministry of Health (MOH) conducted to apply the validation of the questioner.

Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed by using SPSS (version 20) and presented in the suitable method, P-value ≤ .05 considered as significant and 95% of Confidence Interval which 80% the power of the study.

Ethical considerations procedure

Participants got informed consent before answering the questionnaire. In the questionnaire, there are no sensitive and private questions and their identity was anonymous. In addition, an approval was taken from the ethical committee of the research center at King Fahad Medical City.

Results

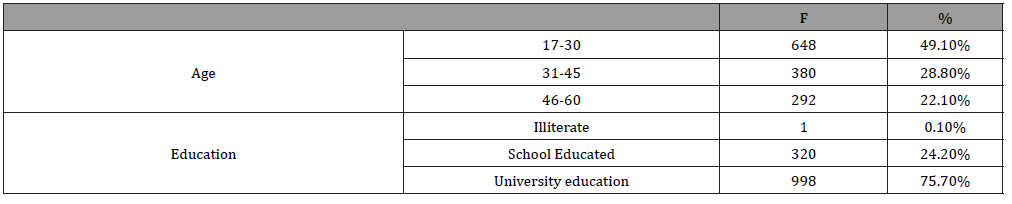

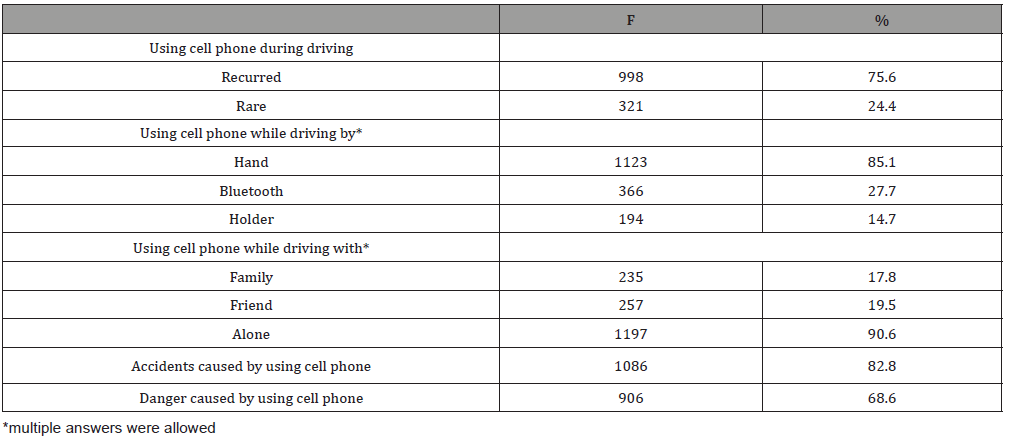

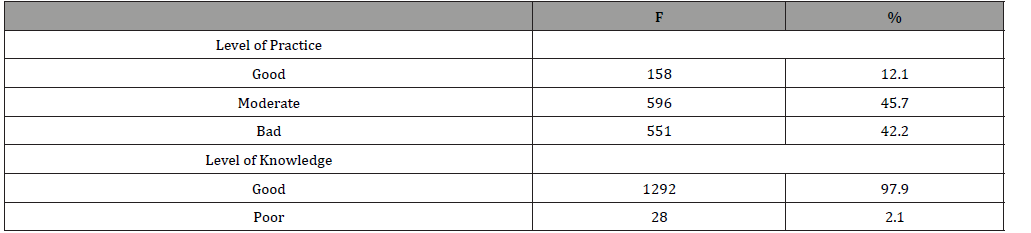

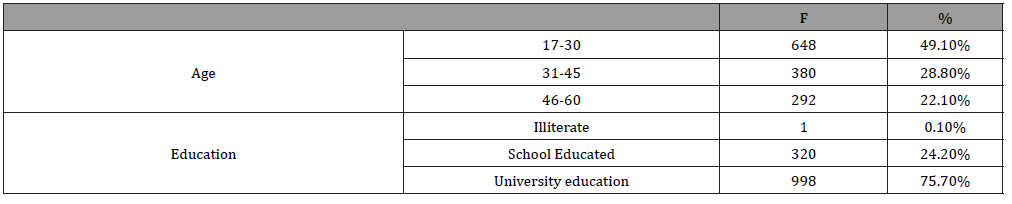

It shows that the drivers aged 17-30 had the highest rate (49.1%) while, most of the drivers on the Academic level (75.7%). Also, most of the drivers using phone by hand (85.1%) and only (14.7%) using holder furthermore, (90.8%) of them use cell phone alone. Moreover, the results of bad and moderate practice were close percentage. (42.2% -45.7 %).

Table 1: Shows the socio- demographic variables among the studied participant.

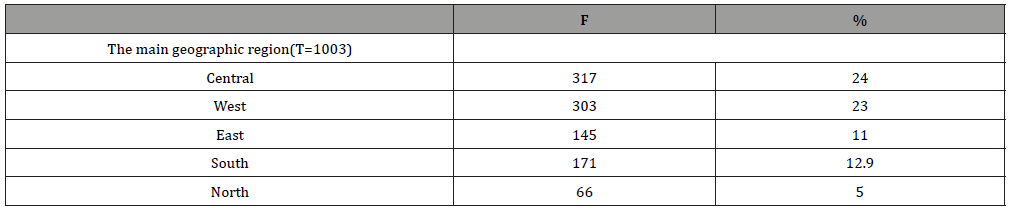

Table 2:Shows the prevalence of cell phone use according to geographic distribution.

Table 3: Shows the practice of cell phone use during driving.

Table 4: shows the level of knowledge and practice.

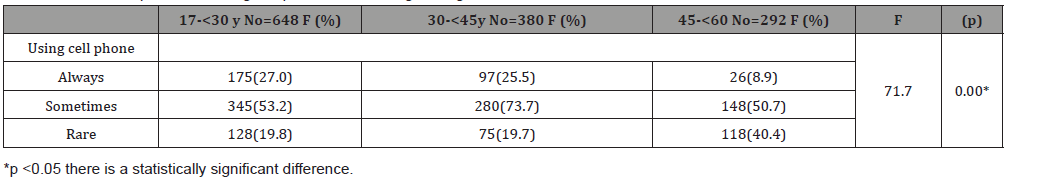

Table 5: Relationship between using cell phone while driving and age.

Table 6: Relationship between using cell phone while driving and age.

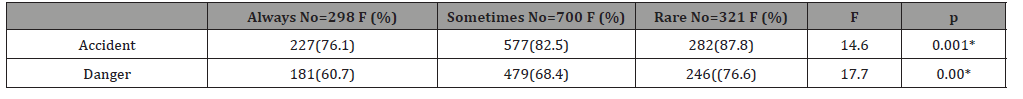

Table 7: shows the relationship between using cell phone while driving and risk of accidents.

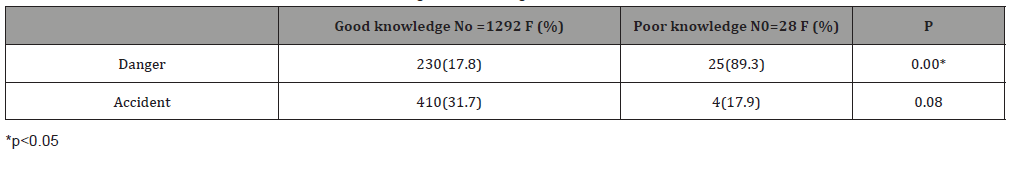

Table 8: shows the association between the level of knowledge and the danger and accident risk.

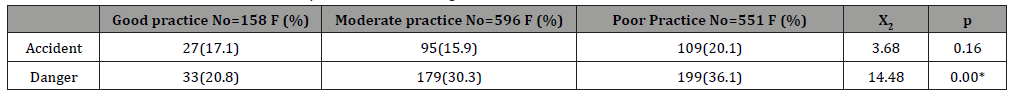

Table 9: shows the association between the practice and the danger and accident risk.

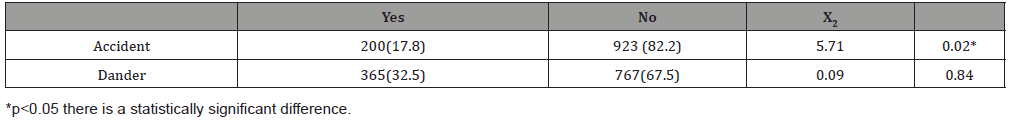

Table 10: shows the Association between accidents and dangers caused by using cell phone while driving by hand-held(T=1123).

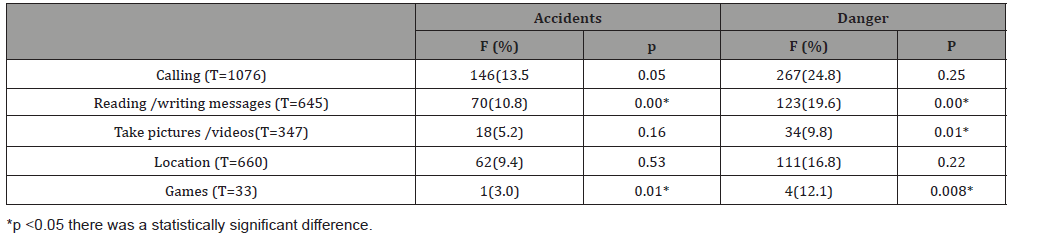

Table 11: The association between accidents and dangers caused by using cell phone with ‘what driver using cell phone for’.

The prevalence of using cellphone while driving and distribution of recurring use for each region. The prevalence was 76% classified as recurring use and 24% as rarely use. While the highest prevalence of recurring use was 24% at the Center and the lowest was 5% in the North. The percentage of using cell phone while driving associated with age and education level. In all age groups the highest percentages who used cell phone ‘’sometimes’’ was (53.2%) among aged 17-30y , (54.7%) among aged 30-<45y and (50.7%) among aged 45-60, while the highest rate of rarely used among aged 46-60 was (40.4%). Moreover, (24%) of academic drivers was higher than educated to using cell phone as always while in ‘’sometimes’’ was higher in educated level than academic with (54.4%). In addition, there is a significant association between using cell phone while driving and age/education level which is highly significant in education level (P-value=.000).

the relationship between using cell phone while driving and the risk of accidents. (82.5%) was answered “sometimes” and (76.1%) answered ‘’Always” accident caused by using cell phone so, there is a significant association between using cell phone while driving and accident p-value (.001). Also, there is a highly inverse significant association between using phone while driving and the danger with a p-value (.000), where drivers who use cell phone “Sometimes” caused by accident was (68.4%) and only (31.6%) who is not. Most of the drivers have a good knowledge which percentage was (97.9%) and only (17.8%) of accidents caused by using cell phone while driving that’s mean there is no significant association between accidents and using cell phone. While, (31.7%) of dangers caused by using cell phone with good knowledge and (14.8%) with poor knowledge also, there is no significant association between dangers and using cell phone.

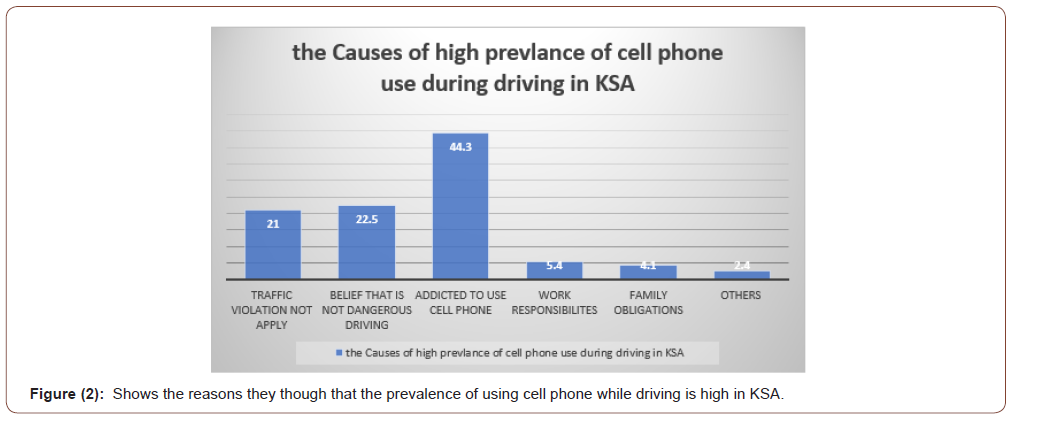

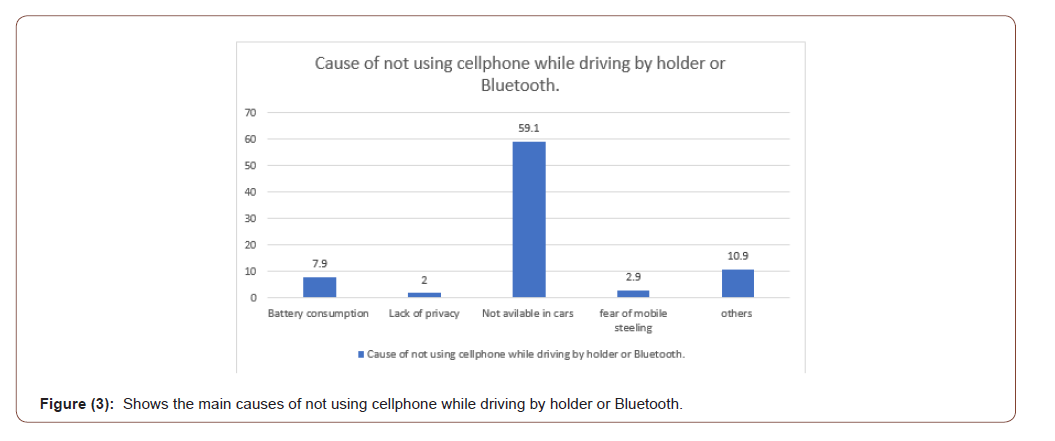

Participants who have bad practice shows to have a higher percentage in accidents and dangers compared to those who have good/moderate practice (20.3% vs. 16.5% / 16%) and (36.2% vs. 20.9%/30%). The chi-square test revealed that there is a significant difference in dangers between different level of practice (p=.001) however no significant difference in accidents. 200 (17.8 %) of those who use it by hand-held exposed to accident and there is a significant relationship with p=0.019. The highest percentage of using cell phone was (81.5%) for calling and the lowest for games (2.6%). The driver who uses calling are more susceptible to accidents caused by using cell phone with (13.5%) and (24.9%) are susceptible to dangers which there is a significant association of accidents caused by using cell phone for calling with p-value (0.05). Also, there is a highly significant association between accidents and dangers caused by using cell phone with reading/ writing messages. Furthermore, the percentages of drivers who use location while driving are (50.8%). The main six common expected causes of a high prevalence of using cellphone while driving. Cell Phone addiction has the highest Percentage (44.3%), while 21% and 22.5% believe that the traffic violation is not applied or it’s s not dangerous to use cellphone while driving. Family obligations are the lowest with 4.1% and 2.4% have different causes. 59.1% of drivers don’t use the Cellphone Holder or Bluetooth while driving because it’s not available in their cars which is the highest percentage and the lowest is the fear of cellphone steeling (2.9%), while 10.9% give a deferent answers of why not using Holders or Bluetooth while driving.

Discussion

In this study 80.2% of the drivers aged between 17-45 using cell phone while driving as recurring use while 40.4% among aged 46-60 of rarely use and there is a highly significant association between using cellphone while driving and age p-value (0.000). In a similar Study conducted in United State shows driver aged 16-24 talked in handheld device more than other age groups. Another study conducted in Saudi Arabia at 2017show there is no statistically significant differences in using mobile phone while driving according to age and education. The prevalence of using cellphone while driving showed 76% of drivers classified as recurring use and 24% as rarely use. In compared to study in Saudi Arabia was conducted in 2017 the prevalence of using cellphone while driving (95.9%) was higher than this study because there is different ranking in question that measures the prevalence, in this study ranked as (Always, sometimes and rarely) while (yes , no) was in the other study. On the other hand, there is a study has a lower prevalence than this study it was conducted in Texas and the main result showed an overall prevalence of using cellphone while driving which is 18.7%.

The drivers in a bad practice 42.2% of them stay on the same path and same speed when using phone and only 12.1% in good practice were their stop on the side road which is 45.7% lowering their speed, in this study there is a high percentage of bad and moderate practice that’s mean drivers need to improve their practice because there was significant association between dangers caused by using cell-phone with practice. While a study conducted in United State in 2016 showed 10.1% stopped when reading a message while driving and 12.7% with any speed. Another study conducted in Washington proved there is 79% of drivers lowering the speed when driving. There was highly significant association between using cell-phone while driving and risk of accident/ dangerous with (p-value 0.001/0.0000) it showed positive correlation between them, which is high percentage of using cellphone will dramatically increase in proportion of accident and dangerous, while 85.1% of drivers using phone by hand-held but there is no significant association between accidents/dangerous caused by using phone while driving and hand-held. In Queensland, 72% of drivers showed that there is a high perceived percentage of accident risk caused by using cellphone for browsing/texting with significant of p-value < 0.001.

In another hand the participants classified as a good or bad knowledge of using cell phone while driving, 97.7% had good knowledge but 76% of drivers still use it and there is no significant association between accidents/dangers caused by using cell phone and the knowledge. Likewise, a study conducted in 2016 showed that there is 97% of adolescent know texting and driving are dangers and they still use cell phone while driving. Approximately 81.5% of drivers are calling while driving which has a significant association with an accident caused by using cell-phone with p-value 0.05, while the second is the location with 50.8% of them and there is no significant association with accidents or dangerous because the location is less distracting. Then the third one is reading/writing message (48.5%) was a highly significant association with accidents and dangerously caused by using cellphone because the main focus will be on the phone and that makes distracting for the drives. Also, 26.3% of drivers taking pictures and only 2.6% of them using games while driving. A study conducted in China showed that’s 17.14% of participants sending text messages, 23.57% making calls, 29.29% reading text message and40% answering calls that’s mean calling is the highest kind of use while driving.

A high prevalence of using cell phone while driving in KSA could be caused by the driver’s addiction to using cell phone (44%). Therefore, 22.5% of respondents think that using cell phone while driving is not dangerous, this can be the reason why most drivers don’t use cell phone with holder or Bluetooth. However, drivers believe that using cell phone is not dangerous while driving is not the main reason but 59.1% use handheld rather than Holder or Bluetooth because it’s not available in their cars. A study conducted in United State shows drivers aged between 16-24 years are talked on the hand-held device more than other age groups.

Limitations

The questionnaire was face to face in the beginning of the study then turned to online questionnaire because the data collectors were distributed in a different region in Saudi Arabi, some of them deal to solve it in face to face and some not.

Conclusion

using cell phone while driving is a prevalent national problem with the highest prevalence in the central region, mainly for calling and reading/writing message, that significantly associated with increased risk of accidents. Its use prevalence varies in different regions in Saudi Arabia. Although the majority of drivers have a good knowledge while they still in a bad practice.

Recommendation

Includes

1) Ministry of Health cooperates with car companies to provide phone holder or Bluetooth in all cars.

2) Increase the amount of traffic violation and make it more effective among drivers.

3) Suggest further researches to study the factors associated with using cell phone while driving.

4)Improve their practice by educated people about the roles of using cell phone while driving.

5)Provide drive mood in all cell phone from technological solutions.

Acknowledgement

A special thanks to the Saudi Ministry of Health (MOH) for allowing us to conduct our research and providing any assistance requested. The authors thank lecturer Dr. Huny Bakry and T. Lama Albashir who were more than generous with their expertise and precious time. Finally, we would like to thank the participants from each region (Center, West, East, North, South), their excitement and willingness to participate made the data collection of this research possible.

Conflict of Interest

No conflict of interest.

References

- (2017) CDC Global Health - Saudi Arabia.

- Fazeen M, Gozick B, Dantu R, Bhukhiya M, González M (2012) Safe Driving Using Mobile Phones. IEEE Transactions on Intelligent Transportation Systems. 13(3): 1462-1468.

- (2017) The Use of Cell Phones While Driving is Dangerous Essay.

- Ahamed H, Hafian M (2016) An investigation of the mobile phone use while driving among drivers: Jeddah, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. International Journal of Applied Research and Studies 8(8).

- (2013) Mobile Device Use While Driving-United States and Seven European Countries, 2011. CDC 62(10): 177-182.

- Hammoudi A, Karani G, Littlewood J (2014) Road Traffic Accidents Among Drivers in Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates. Journal of Traffic and Logistics Engineering 2(1): 7-12.

- Oviedo Trespalacios O, King M, Haque M, Washington S (2017) Risk factors of mobile phone use while driving in Queensland: Prevalence, attitudes, crash risk perception, and task-management strategies. PLoS One 12(9): e0183361.

- (2013) The impact of hand-held and hands-free cell phone use on driving performance and safety-critical event risk. National Highway Traffic Safety Administration, pp. 3, Washington DC, USA.

- Charlotte L Brace, Kristie L Young, Michael A Regan (2017) Analysis of the literature: The use of mobile phones while driving.

- (2017) Twitter. Available from: https://twitter.com/eMoroor/status/893411378890932224.

- Strayer D, Drews F, Crouch D (2006) A Comparison of the Cell Phone Driver and the Drunk Driver. Human Factors: The Journal of the Human Factors and Ergonomics Society 48(2): 381-391.

- (2017) Riyadh Traffic.

- (2017) Using mobile phones when driving - GOV.UK.

- S Ameratunga, M Hijar, R Norton (2006) Road-traffic injuries: Confronting disparities to address a global-health problem. Lancet 367 (9521): 1533-1540.

- AK Abbas, AF Hefny, FM Abu Zidan (2011) Seatbelt compliance and mortality in the gulf cooperation council countries in comparison with other high-income countries. Ann Saudi Med 31(4): 347-350.

- A Bener, T Özkan, T Lajunen (2008) The driver behaviour questionnaire in arab gulf countries: Qatar and United Arab Emirates. Accid Anal Prev 40(4): 1411-1417.

- Begum M, Maheswari R (2017) A Case Study on the Awareness and Usage of Mobile Phone in Coimbatore District. Asian Journal of Research in Marketing 6(5):1-23.

- Sanbonmatsu D, Strayer D, Biondi F, Behrends A, Moore S (2015) Cell-phone use diminishes self-awareness of impaired driving. Psychon Bull Rev 23(2): 617-623.

- Jawadi AH, Alolayan LI, Alsumai TS, Aljawadi MH, Philip W, et al. (2017) Seat belt usage and distracted driving behaviors in Saudi Arabia: Health-care providers versus nonhealth-care providers. J Musculoskelet Surg Res 17(1): 10-15.

- Bergmark R, Gliklich E, Guo R, Gliklich R (2016) Texting while driving: the development and validation of the distracted driving survey and risk score among young adults. Inj Epidemiol 3(1): 7.

- Billieux J, Maurage P, Lopez Fernandez O, Kuss D, Griffiths M (2015) Can Disordered Mobile Phone Use Be Considered a Behavioral Addiction? An Update on Current Evidence and a Comprehensive Model for Future Research. Curr Addict Rep 2(2): 156-162.

- McDonald C, Sommers M (2015) Teen Drivers’ Perceptions of Inattention and Cell Phone Use While Driving. Traffic Inj Prev 2(0): S52-S58.

- Al Reesi H, Al Maniri A, Plankermann K, Al Hinai M, Al Adawi S, et al. (2013) Risky driving behavior among university students and staff in the Sultanate of Oman. Accid Anal Prev 58: 1-9.

- Rasool F, Alekri F, Nabi H, Naiser M, Shamlooh N, et al. (2015) Prevalence and behavioral risk factors associated with road traffic accidents among medical students of Arabian Gulf University in Bahrain. International Journal of Medical Science and Public Health 4(7): 933.

- Wilkinson M, Brown A, Moussa I, Day R (2015) Prevalence and correlates of cell phone use among Texas drivers. Preventive Medicine Reports 2: 149-151.

- Rudisill T, Zhu M (2017) Hand-held cell phone use while driving legislation and observed driver behavior among population sub-groups in the United States. BMC Public Health 17(1): 437.

- Kumar V, Dewan D, Kumar D (2017) Injury and violence related behaviour among school-going adolescents in Jammu region. IJCMPH 4(9): 3155.

- Zhou R, Yu M, Wang X (2016) Why Do Drivers Use Mobile Phones While Driving? The Contribution of Compensatory Beliefs. PLoS One 11(8): p.e0160288.

- Delgado M, Wanner K, McDonald C (2016) Adolescent Cellphone Use While Driving: An Overview of the Literature and Promising Future Directions for Prevention. Media Commun 4(3): 79-89.

- Parr M, Ross L, McManus B, Bishop H, Shannon M O Wittig, et al. (2016) Differential impact of personality traits on distracted driving behaviors in teens and older adults. Accid Anal Prev 92: 107-112.

- Farmer C, Klauer S, McClafferty J, Guo F (2015) Relationship of Near-Crash/Crash Risk to Time Spent on a Cell Phone While Driving. Traffic Inj Prev 16(8): 792-800.

- Cazzulino F, Burke R, Muller V, Arbogast H, Upperman J (2013) Cell Phones and Young Drivers: A Systematic Review Regarding the Association Between Psychological Factors and Prevention. Traffic Inj Prev 15(3): 234-242.

- Brubacher J, Chan H, Purssell E, Tuyp B, Ting D, et al. (2017) Minor Injury Crashes: Prevalence of Driver-Related Risk Factors and Outcome. J Emerg Med 52(5): 632-638.

- Martin J, Kauer S, Sanci L (2018) Road safety risks in young people attending general practice: A cross-sectional study of road risks and associated health risks. Aust Fam Physician 45(9): 666-672.

- (2018) The United Arab Emirates Government Portal, UAE.

- (2018) Road safety Available from: https://government.ae/en/information-and-services/justice-safety-and-the-law/road-safety.

- (2018) [Internet]. Traffic.gov.bh. Available from: http://www.traffic.gov.bh/contravention/department-of-irregularities/department-of-irregularities.

- amman Jordan (2018)

- (2017) Road traffic injuries. World Health Organization.

-

Randah Al alweet, Alanoud Nugali, Samar A Amer. Using Cellphone While Driving Among Saudi Drivers in Saudi Arabia, Cross Section Study 2018. 1(2): 2020. APHE.MS.ID.000506.

-

Cell phone use, Driving, Accident, KSA, Behavior, Injuries, Violence, Sexuality, Danger, Crash risk.

-

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.