Case Report

Case Report

Child with Sporadic Hemiplegic Migraine: Case Report

Giovanna Ferreira Gomes¹*, Danielle Silva Borges¹*, Amanda Vieira Sacardo¹*, Bianca Azevedo Santos¹*, Gustavo Mota Faria¹*, Caio Hespanhol Ferreira¹*, Andrey Mirando Tiveron¹*, Nícolas da Cunha Leite Borges¹*, Douglas Reis Abdalla1,3 and Josephine Marie Da Cunha Fish Cardoso1,2

1Medicine Course, University of Uberaba, Brazil

2Children’s Hospital, Uberaba, Minas Gerais, Brazil

3Health Courses, Faculty of Human Talents, Brazil

Douglas Reis Abdalla, Av. Tonico dos Santos, 333 – Jardim Induberaba Uberaba, Minas Gerais, Brazil. (Authors contributed equally to the development of this work)

Received Date: December 08, 2020; Published Date: December 23, 2020

Hemiplegic migraine is a rare condition, which consists of a migraine with an aura, this being a unilateral motor weakness. It can be divided into familial or sporadic, according to whether or not similar cases are present in first-degree families. Its pathophysiology includes endogenous and exogenous factors. A case report was made of a 9-year-old female patient who presented four episodes with symptoms such as syncope, left hemiplegia, dizziness, visual blurring, among others. After ruling out other causes of hemiplegia, the diagnosis of sporadic hemiplegic migraine was closed. The patient presented with an atypical presentation of hemiplegic migraine, since she did not present with headache, which can occur in 1 to 5% of patients. However, symptoms such as unilateral paresthesia of limbs with a reversible pattern made it possible to classify her in this diagnosis. The treatment recommended for crisis prevention includes Sodium Valproate, which was recommended to her. Thus, the importance of performing a thorough clinical examination associated with imaging examinations for diagnoses of cases that are not normal is evident.

Keywords:Migraine with aura; Headache; Hemiplegic migrain

Introduction

Hemioplegic migraine (HM) is a rare variant, characterized by a migraine accompanied by aura, which consists of a totally reversible unilateral motor weakness and the presence of at least one other sign of aura which is also reversible, the most common being sensory, visual and speech problems (dysphasia), there are also socalled “ basilar “ symptoms which may be present such as dizziness, instability and tinnitus [1]. The aura symptoms last for more than 5 minutes and less than 24 hours, and the other associated symptoms can occur concomitantly or successively with the aura episode [2]. It is possible to differentiate it in Family Hemioplegic Migraine, in which the presence of at least one first or second degree relative with the same conditions is necessary, that is, with aura including muscle weakness, and in Sporadic Hemioplegic Migraine which occurs in an individual sporadically with no family history of HM [3]. The prevalence of hemiplegic migraine is 1 in 10,000, with family hemiplegic migraine (FHM) and sporadic hemiplegic migraine (SHM) being equally frequent [4].

Typical episodes of hemiplegic migraine are characterized by motor weakness, which is always associated with other symptoms of aura, with the most frequent changes being sensory, visual and speech. Additionally, basilar type symptoms - vertigo, visual field changes such as diplopia, and even partial loss of vision, numbness and paresthesias, speech difficulties (dysarthria), loss of coordination (ataxia), vomiting - occur in up to 70% of patients. Severe attacks can occur in both FHM and SHM with prolonged hemiplegia, confusion, coma, fever and seizures. The clinical spectrum also includes permanent cerebellar signs (nystagmus, ataxia, dysarthria) and less frequently several types of seizures and mental retardation [5]. Familial hemiplegic migraine is caused by typical migraine stimuli, such as food, odors, stress, minor cranialtrauma and cerebral angiography. Neurological symptoms of the aura are clearly localized in the cerebral cortex or the brainstem and include visual disturbances (most common, such as scotomas, photopsies, fortification spectra and diplopia), sensory loss (numbness or paresthesias of the face or one end) and dysphasia (difficulty with speech, which usually occurs when the hemiplegia is on the right side), and to be FHM must include motor involvement (hemiparesis) [6]. Hemiparesis occurs with at least one other symptom during the aura of FHM [7].

The weakened consciousness (from drowsiness, confusion and even coma) is well described at FHM, even without the presence of dysphasia [8,9]. Neurological deficits with HM attacks can be prolonged for hours to days and can last longer than the associated migraine. Persistent attention and memory loss can last for weeks to months 10. Permanent motor, sensory, linguistic or visual symptoms are extremely rare [7]. Brain infarction and death have rarely been associated with HM and the possibility of other disorders associated with migraine and stroke should instead be raised [5]. Sporadic hemiplegic migraine refers to simple cases, i.e. individuals affected but without relatives with hemiplegic migraine, and these individuals may or may not have other family members with typical migraine [5]. The pathophysiology of migraine includes both endogenous and exogenous (environmental) factors that may act as triggers of the crisis. The physiopathology of migraine is discussed according to various theories [11].

One of the theories discussed is that of the spreading depression of Lion, in which there is a depolarization of the electrical activity propagated by the cortex, due to its abnormal excitation, and this can be the cause for triggering a crisis [12]. There is also the theory that addresses the relationship of serotonin with migraine, by identifying the metabolite of 5-HT acid in the urine of patients with migraine. Furthermore, it is discussed about the genetic issue influencing the appearance of the disease, due to the fact that chromosomal mutations have been observed in genes that encode proteins involved with calcium channels, P/Q type dependent voltage specific to the brain, which make the transport of ions [12].

Finally there is the vascular theory in which a vasoconstriction was observed, with a consequent vasodilation that would cause the pain. Given the above, it can be seen that various theories are analysed and discussed to explain the physiopathology of migraine, and it is a fact that migraine is a multifactorial disease, with numerous crisis triggers [11].

The report will be conducted with the aim of presenting the particularities involved in the clinical case in order to improve and expand knowledge about hemiplegic migraine in order to provide better care and improve the health conditions of the population.

Case Report

Patient V.O.A, female, nine years and ten months, faioderma, natural and from Uberaba, Minas Gerais, daughter of healthy parents. The patient was admitted to the Emergency Room of the Children’s Hospital in May 2020, accompanied by her mother, who reported a syncope picture accompanied by loss of consciousness. At the same time, she reported confusion and visual blurring. He denied sphincter release, headache, cranial trauma, fasting, fever, cough, and palpitations preceding the picture. In view of this, laboratory tests were performed which showed an anemic picture. The child was only under observation and was discharged later. On August 11, 2020, the mother reported a global loss of strength, in upper and lower limbs, which resulted in a fall to the ground from her own height. At the same time, she reported feeling dizziness, sweating, abdominal pain and asthenia. After 4 hours, there was full recovery of strength. After 6 days, the same picture was repeated. On August 17, 2020, the mother reported left hemiplegia in the upper and lower limbs while walking. Concomitant to the loss of strength of the limbs, the child presented dizziness, sweating, abdominal pain, nausea, skin pallor and change in sensitivity of the face. After the episode, he reported dizziness and persistence of hemiplegia. After 40 minutes, he sought the emergency room of the Children’s Hospital.

On general physical examination, the child showed abdominal pain on superficial and deep palpation in the right flanks and hypochondrium. Regarding the neurological examination, dysmetria, dysdiadokinesia, lentification of movements, altered coordination (negative index-nariz test) and fall of the left upper limb after placing both limbs extended. On examination of the locomotor apparatus, Mingazzini was positive in the left lower limb, loss of strength of the left limbs and Babinski was negative. In view of the alterations presented, she was referred to hospital for complementary examinations, having as diagnostic hypothesis a Deficitary Motor Syndrome, having as possible etiologies Hemiplgic Migraine and Temporal Wolf Epilepsy. In addition, Depakene 250 mg/5ml was prescribed and hemogram, ionic evaluation and electrocardiogram were requested, whose results showed no alterations. With one day of hospitalization, the patient underwent an evaluation with the neuropediatrician showing discrete balance in orthostatic position, Romberg positive, negative Rechaço maneuver, without changes in the cranial nerves, discrete fractionation of the movement of the left upper limb, deep reflexes with discrete reduction and positive Mingazzini in the left lower limb. A reduction of the left hemicorp muscle strength was identified, being this grade 1 or 2 predominant in the lower limb. On the right side the strength was grade 5. The resting electroencephalogram was performed, with the result evidencing disorganization of the basic activity. From that, a Computed Tomography of the Skull was requested to confirm or rule out the hypotheses of Hemioplegic Migraine and Temporal Wolf Epilepsy. In addition, Sodium Valproate 250 mg, twice a day, was prescribed in conjunction with the medication in use.

After two days of hospitalization, the child presented a significant improvement of the hemiplegic picture with absence of other neuro-motor alterations. On the same day, a Computed Tomography of the Skull was performed, which showed no alterations. The patient was discharged from hospital with suspension of medications in use and was referred for outpatient follow-up with the neuropediatrician in September. On September 8, 2020 the child attended the neuropediatric outpatient clinic for outpatient follow-up. He denied new episodes and subsequent symptoms. She reported as pre-existing diseases Ceratocone and Epilepsy and as drugs in continuous use Patanol S colirio and Depakene in a dosage of 5 ml every 12 hours. Denied urinary and intestinal alterations. As personal antecedents mother reported uneventful vaginal delivery in pregnancy and delivery, and a previous pathological history of an episode of brain trauma (TBI) when the child was still infant. As family history the mother reported that she does not have comorbidities, the father is a user of illicit drugs, the maternal grandmother is hypertensive and diabetic and maternal grandfather hypertensive. In addition, she denied history of epilepsy in the family. The child was eutrophic, with neuropsychomotor development appropriate for the age and without changes in physical examination. As the skull tomography already performed showed no changes and the Electroencephalogram showed a discrete disorganization of the tracing and slow waves in medial regions was taken as conduct the repetition of the Electroencephalogram in 6 months and return after it was performed. Finally, as diagnostic hypotheses the presence of Epilepsy or Hemioplegic Headache were questioned. Thus, due to the absence of EEG alterations, the diagnosis of Hemioplegic Migraine was closed, by diagnosis of exclusion.

Finally, the child returned to the neuropediatric clinic on November 10, 2020 reporting a new episode of lethargy, paresis, visualization of floaters and intense sweating for 9 days lasting 20 minutes. He denied the presence of loss of consciousness and amnesia. She was admitted to the Children’s Hospital of Uberaba and the hypothesis of urinary tract infection was raised due to a finding of leukocyturia, thus antibiotic therapy was initiated, however uroculture brought as a result the absence of bacterial growth being suspended the medication. On October 7, 2020 the child presented again the picture described above with a duration of 20 minutes, as in the previous one, and referred visualization of floaters for 12 hours before the crisis. The mother reported that the patient presented at least seven similar episodes since June and after the beginning of Depakene medication, at a dosage of 5 ml every 12 hours, the child has been showing mania for cleaning and signs of hyperactivity. During the consultation, neurological alterations were found that in previous episodes were not found. A decrease in the visual field on the right side was seen and the balance was altered. The coordination and deep reflexes were preserved. Hemiplgic migraine was again mentioned as a diagnostic hypothesis, and along with these a picture of anxiety disorder and obsessive compulsive disorder was added. As a conduct the dose of Depakene was increased to 7.5 ml every 12 hours and a herbal medicine was prescribed. The child will return for follow-up 2 weeks after the start of the new treatment.

Discussion

Although the term “plégic”, contained in the word hemiplegic, means paralysis in most languages, when used to characterize hemiplegic migraine (HM), in most cases the crises are actually accompanied by a picture of motor weakness (paresis)³. Thus, the main presentation of the patient in question is a left hemiparesis. The typical clinical picture of a patient with HM with aura contemplates visual disorders, unilateral and reversible limb paresthesia, convulsions, fever, lethargy, speech impairment, aphasia and numbness. In addition, patients have a basilar type aura that includes vertigo, diplopia, mental confusion and loss of consciousness. It is worth noting that symptomatic seizures are intermittent and may have a variable frequency of hours to weeks13. In relation to the case of the patient in question, her episodes also occur unexpectedly and with a diversified clinical picture, and she cannot be able to define any trigger triggering the crises. In addition, the child presents some of the typical symptoms of patients with this disease, such as temporary paresthesia, blurred vision, unconsciousness and balance disorders. However, headache accompanied by nausea/ vomiting and convulsive episodes that correspond to the most typical clinical manifestations of the patient with Hemioplegic Migraine, the child in question did not report any of the three events that occurred. Nevertheless, it is found that some patients never present headache among the clinical manifestations of HM, as it occurs in 1 to 5% of people [14,15,3].

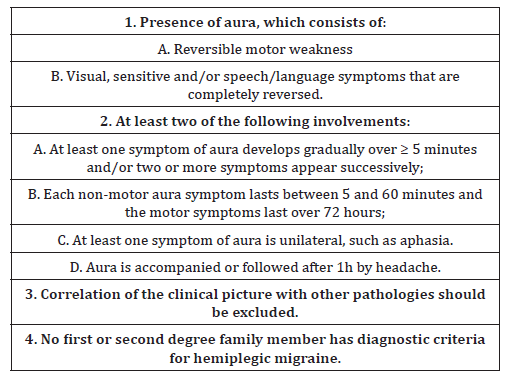

Table 1:Representation of diagnostic criteria for hemiplegic migraine.

There are two types of hemiplegic migraine. One is characterized by the presence of at least one first or second degree family member who has had attacks of HM, and is therefore called Family Hemiplegic Migraine (FHM). The other type is characterized by the absence of a family history of the disease and is called Sporadic Hemiplegic Migraine (SHM) [16,17]. According to the International Classification of Headaches (2014)3, the diagnosis of sporadic hemiplegic migraine requires at least two attacks meeting the criteria presented in chart 117 (Table 1).

In the clinical case mentioned above, the patient can be classified as SHM, since she presents in her clinical history more than two attacks, including criteria 1A, 1B, 2A, 3 and 4, which have already been described throughout the case. Mostly, the diagnosis of this pathology is clinical, being made from a detailed anamnesis and a physical examination, mainly neurological. However, in cases of diagnostic doubts, neuroimaging tests may be requested. Cerebral Magnetic Resonance is indicated for patients with hemiplegic migraine, in order to exclude other pathologies, especially in cases where the aura always occurs on the same side. The presence of permanent abnormalities in skull tomography and brain magnetic resonance imaging examinations in patients with HM is rare, and alterations can be found during or soon after the attacks, and these are related to vascular and neuronal mechanisms. The most frequently reported alteration in these exams is the presence of diffuse edema (cortical) of the hemisphere contralateral to the motor deficit, which is consistent with the clinic of loss of motor strength of the limbs18. In the case under study, brain magnetic resonance imaging was not performed, only skull tomography was performed, which did not show specific alterations. The electroencephalogram (EEG) is also used as a support to diagnose hemiplegic migraine. It is possible to observe alterations such as the presence of diffuse unilateral slow waves (theta and/or delta activity) in the contralateral hemisphere next to the motor symptoms during or soon after the crisis. An electroencephalogram was performed on the child, which demonstrated a discrete disorganization of the tracing and slow waves in medial regions that match alterations found in the presence of hemiplegic migraine. When hemiplegic migraine is associated with epileptic seizures it is possible to observe peak and wave EEG complexes, but this finding was not found in the case under discussion. Brain angiography done in a conventional way or by magnetic resonance also helps in the diagnosis of hemiplegic migraine. It is possible to observe narrowing or even obliteration of the coronary arteries in the acute phase, but it is not followed by signs of ischemia in any case. Finally, the presence of lymphocytosis and increased protein levels during the attack of HM can be found through the study of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), but this procedure was not done in the case described [17]. The genetic test, although not performed in the case in question, due to the fact that the care in the Unified Health System where the diagnostic resources are limited, is another form of diagnosis for HM. Genetic screening is more useful in sporadic cases of early onset, when accompanied by a neurological clinic, or when there are cases in which the symptoms differ in severity from the affected relatives. The identification of the genetic mutation can lead to a definitive diagnosis, avoiding the carrying out of numerous unnecessary tests, but it is worth pointing out that the family hemiplegic migraine proves to be a multifactorial disease and many genes may be involved [19]. The genes that cause migraine and the genes involved in the susceptibility of migraine cases can guide the general pathways involved in the pathological mechanisms that lead to the clinical phenotypes of each one of them. Family Hemioplegic Migraine can be caused by three mutations, in different genes: FHM type 1 is caused by mutations in the CACNA1A gene in a calcium channel, FHM type 2 by mutations in the ATP1A2 gene, in the Na + / K + glial pump and FHM type 3 by mutations in the SCN1A gene, in a voltage controlled sodium channel. Some patients do not present mutations in these genes, being other complex phenotypes involved in the mechanism of the disease20. In SHM, in some patients the same genes causing FHM1, FHM2 and FHM3 were identified. However, different factors, genetic and environmental, seem to play some role in SHM. Moreover, some cases may still result from incomplete penetrance, i.e., when there are family members who are asymptomatic carriers of the mutation [21,22].

Even being chronic pathologies that have distinct clinical manifestations, migraine and epilepsy have some overlapping symptoms and pathophysiology. Both are episodic disorders. Thus, sporadic attacks occur and, among them, the patients are asymptomatic, this being a variable period. These episodic disorders are of a paroxysmal nature, that is, when a triggering factor may induce to an aberrant stage, by a reduced barrier, generating a pathological phenotype. There is unproven evidence of comorbidity among some types of migraine and epilepsy, as can occur in FMH [20,21]. In the case reported, there were diagnostic doubts between the two clinical pictures because of the similarities of the pictures. The treatment of HM is based primarily on avoiding triggering factors such as stress, especially strong lights, sleep disorders, physical effort and certain beverages and foods [17]. In addition, there is the pharmacological treatment that can be divided into two stages: seizures and basic (daily). For seizures, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (Cetoprofen, Aspirin), antiemetic neuroleptics (Metoclopramide) can be used, while maintenance can be done with effective anti-epileptic agents to prevent migraine with aura (Topiramate, Sodium Valproate, Lamotrigine) and other anti-migraine treatments (Beta Blockers, Calcium Antagonists, Tricyclic Antidepressants) [1]. In the above case, after the last hospitalization, Sodium Valproate (Depakene) was prescribed as daily treatment for HM.

Conclusion

In this case, the importance of a good clinical examination associated with imaging exams and the electroencephalogram and the knowledge of the literature is evident, since the diagnosis as seen in the case described is not easy because it escapes from normality and does not include the main symptom. It has been demonstrated that the patient with Hemioplegic Migraine can have several particularities which can even cause the diagnosis to be confused with that of other diseases. Moreover, the main symptoms are not always present, making it even more difficult to identify the real disease. Therefore, a thorough clinical examination concatenated with imaging exams and electroencephalogram are of utmost importance to guide the investigation, exclude differential diagnoses and give a good treatment to the patient.

Acknowledgement

None.

Conflict of Interest

No conflict of interest.

References

- DUCROS Anne, COMTE Gaële, Hemiplegic migraine (2010) Orphanet Translation Portugal.

- DOMINGUES, João Roberto Sala, ROMERO, Daniela Fernanda Bonvino, ESPOSITO, Sandro Blasi (2005) Sporadic hemiplegic migraine. Journal of the Faculty of Medical Sciences of Sorocaba 7(1): 23-26.

- KOWACS Fernando, MACEDO Djacir Dantas Pereira de; SILVA-NÉTO (2019) Raimundo Pereira da. International Classification of Headaches. 3. Ed. São Paulo: Headache Classification Committee of the International Headache Society 118 p. Translation of the Brazilian Headache Society with authorization from the International Headache Society.

- DUCROS Anne (2008) Familial and sporadic hemiplegic migraine. Rev Neurol (Paris) 164(3): 216-224.

- Jen JC. Familial Hemiplegic Migraine. 2001 Jul 17 [Updated 2015 May 14]. In: Adam MP, Ardinger HH, Pagon RA, et al, editors. GeneReviews®️ [Internet]. Seattle (WA): University of Washington, Seattle; 1993-2020.

- THOMSEN L Lykke, ERIKSEN M Kirchmann, ROMER S Faerch, ANDERSEN I, OSTERGAARD E, et al. (2002) An Epidemiological Survey of Hemiplegic Migraine. Cephalalgia, [S.L.] 22(5): 361-375.

- DUCROS Anne, DENIER Christian, JOUTEL Anne, CECILLON Michaëlle, LESCOAT Christelle, et al. (2001) The Clinical Spectrum of Familial Hemiplegic Migraine Associated with Mutations in a Neuronal Calcium Channel. New England Journal of Medicine [S.L.] 345(1): 17-24.

- Terwindt G, Ophoff R, Haan J, LA Sandkuijl, RR Frants, et al. (1998) Migraine, ataxia and epilepsy: a challenging spectrum of genetically determined calcium channelopathies. Eur J Hum Genet 6: 297-307.

- Vahedi K, Denier C, Ducros A, Bousson V, Levy C, et al. (2000) CACNA1A gene de novo mutation causing hemiplegic migraine, coma, and cerebellar atrophy. Neurology, [S.L.] 55(7): 1040-1042.

- KORS Esther, HAAN Joost, FERRARI Michel (2003) Migraine genetics. Current Pain and Headache Reports [S.L.] 7(3): 212-217.

- VINCENT MAURICE B (1998) Pathophysiology of migraine. Arq. Neuro-psiquiatr 56(4): 841-851.

- Speciali Jose Geraldo (2016) Fleming Norma Regina Pereira, Ida Fortini. Primary headache: dysfunctional pain. Rev pain 17(Suppl 1): 72-74.

- HIEKKALA, Marjo Eveliina, VUOLA Pietari, ARTTO Ville, HÄPPÖLÄ Paavo, et al. (2018) The contribution of CACNA1A, ATP1A2 and SCN1A mutations in hemiplegic migraine: a clinical and genetic study in finnish migraine families. Cephalalgia, [S.L.] 38(12): 1849-1863.

- WANNMACHER, Lenita, FERRERIA, Maria Beatriz Cardoso (2004) ., Brasília 1(8): 1-6.

- FIGUEIRA, Maria Maria Gomes da Silva Morais. Migraine-Epilepsy Relationships. 2009. 20 f. Thesis (Master) - Medical Course, Abel Salazar Institute of Biomedical Sciences, Porto, 2009.

- Pelzer N, Haan J, Stam AH, Vijfhuizen LS, Koelewijn SC, et al. (2018) Clinical spectrum of hemiplegic migraine and chances of finding a pathogenic mutation. Neurology 90(7): e575-e582.

- PELZER, Nadine, STAM, Anine H, HAAN, Joost. et al. (2013) Familial and Sporadic Hemiplegic Migraine: Diagnosis and Treatment. Curr Treat Options Neurol 15: 13-27.

- SUGRUE Gavin, BOLSTER Ferdia, CROSBIE Ian, KAVANAGH Eoin (2014) Hemiplegic Migraine: neuroimaging findings during a hemiplegic migraine attack. Headache: The Journal of Head and Face Pain, [S.L.] 54(4): 716-718.

- Russell MB, Ducros A (2011) Sporadic and familial hemiplegic migraine: Pathophysiological mechanisms, clinical characteristics, diagnosis, and management. Lancet Neurol.

- MANTEGAZZA Massimo, CESTÈLE Sandrine (2018) Pathophysiological mechanisms of migraine and epilepsy: similarities and differences. Neuroscience Letters, [S.L.] 667: 92-102.

- PEIXOTO, Maria João Canavez (2011) Migraine Genetics. 2011. 35 f. Thesis (Master) - Medical Course, University of Porto, Institute of Biomedical Sciences Abel Salazar, Porto.

- FERRARI Michel D, Roselin R Klever, Gisela M Terwindt, Cenk Ayata, Arn M J M van den Maagdenberg, et al. (2015) Migraine pathophysiology: lessons from mouse models and human genetics. The Lancet Neurology 14(1): 65-80.

- Irene de Boer, Arn MJM van den Maagdenberg, Gisela M Terwindt (2019) Advance in genetics of migraine. Current Opinion in Neurology 32(3): 413.

-

Giovanna Ferreira G, Danielle Silva B, Amanda Vieira S, Bianca Azevedo S, Gustavo Mota F, et al., Child with Sporadic Hemiplegic Migraine: Case Report. Arch Neurol & Neurosci. 9(3): 2020. ANN.MS.ID.000714.

-

Migraine with aura; Headache; Hemiplegic migraine, scotomas, photopsies, fortification spectra diplopia, migraine, Motor Syndrome, physiopathology of migraine.

-

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.