Research Article

Research Article

A Preliminary Survey Regarding Suicidal Conduct among Iranian Juvenile Psychiatric Inpatients

Saeed Shoja Shafti*1, Alireza Memarie2, Masomeh Rezaie2 and Masomeh Hamidi2

1Professor of Psychiatry, University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences (USWR), Iran

2Razi Psychiatric Hospital, Iran

Saeed Shoja Shafti, Professor of Psychiatry, University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences (USWR), Razi Psychiatric Hospital, Tehran, Iran.

Received Date: May 27, 2019; Published Date: May 29, 2019

Abstract

Introduction: Suicidal behavior is seen in the context of a variety of mental disorders and while many believe that, in general, first episode psychosis is a particularly high-risk period for suicide, no general agreement regarding higher prevalence of suicide in first episode psychosis is achievable. In the present study, suicides and suicide attempts among child and adolescent psychiatric in-patients has been evaluated to assess the general profile of suicidal behavior among native psychiatric inpatients.

Methods: All child and adolescent psychiatric inpatients with suicidal behavior (successful suicide and attempted suicide, in total), during the last five years (2013-2018), had been included in the present investigation.

Result: Among 748 child and adolescent psychiatric patients hospitalized in razi psychiatric hospital during a sixty months’ period, 14 suicide attempts, without any successful suicide, had been recorded by the safety board of hospital. The most frequent mental illness was bipolar I disorder (50%), followed by conduct disorder (42.85%), and substance abuse disorder (7.14%), with no significant difference among them. Self-mutilation, self-poisoning and hanging were the preferred methods of suicide among 60%, 20% and 20% of cases, respectively. In addition, no significant difference was evident between the first admission and recurrent admission inpatients, totally and separately

Conclusion: While in the present study the suicidal behavior was non-significantly more evident in bipolar disorder in comparison with other psychiatric disorders, no significant difference was evident between first admission and recurrent admission child and adolescent psychiatric inpatients.

Keywords: Child and adolescent; Psychiatric disorders; Suicide; Suicide attempt; First admission; Recurrent admission; Bipolar disorder; Conduct disorder; Substance Abuse disorder

Introduction

The WHO report “Preventing suicide: a global imperative” published in 2014 estimates that over 800,000 people die by suicide, and more than 20 million attempt suicide each year. This implies that every 40 seconds, a person dies by suicide somewhere on the globe, and every 1.5 seconds, someone will attempt to take his/ her own life. However, those numbers are underreported, as not all countries in the world report suicide mortality to the WHO Globally, suicides account for 52 percent of all violent deaths in men and 71 percent of all violent deaths in women. In high-income countries, 79 percent of violent deaths in both males and females are caused by suicide. Suicide occurs in all regions of the world and throughout the life span, and it accounts for 1.4 percent of all deaths worldwide, by that, ranking as the 15th leading cause of death [1]. Suicide is rare in childhood and early adolescence and becomes more frequent with increasing age. The latest mean worldwide annual rates of suicide per 100 000 were 0.5 for females and 0.9 for males among 5-14-year-olds, and 12.0 for females and 14.2 for males among 15-24-year-olds, respectively. In most countries, males outnumber females in youth suicide statistics. Although the rates vary between countries, suicide is one of the commonest causes of death among young people. Due to the growing risk for suicide with increasing age, adolescents are the main target of suicide prevention. Reportedly, less than half of young people who have committed suicide had received psychiatric care, and thus broad prevention strategies are needed in healthcare and social services. Primary care clinicians are key professionals in recognizing youth at risk for suicide [2]. In ten years follow up of eighty-eight subjects with adolescent-onset psychotic disorders, mainly schizophrenia and affective disorders, 4.5% of subjects had died from suicide while another 25% of the subjects had attempted suicide [3]. In the context of suicide, there is a growing body of evidence showing that exposure to earlylife maltreatment can affect molecular mechanisms involved in the regulation of behavior through methylation and histone modification, supposed to induce behavioral deviations during the early development, and possibly later in life, affect genes involved in crucial neural processes. This mechanism is called epigenetics. Childhood abuse and other detrimental environmental factors seem to target the epigenetic regulation of genes involved in the synthesis of neurotrophic factors and neurotransmission [4]. On the other hand, some scholars believe that People with first episode psychosis (FEP) are at increased risk of premature death, in particular suicide [5]. According to the findings of a study, the rate of attempted suicide among young people undergoing treatment for first episode psychosis was around 12%. Of these 72.6% attempted suicide on one occasion. 85.3% of attempts occurred when patients were treated as outpatients and were in regular contact with the service.77.6%of suicide attempts tended to be impulsive triggered by interpersonal conflict or distress due to psychotic symptoms. Two thirds involved self-poisoning, usually by overdose of prescribed medications. All inpatient suicide attempts were by hanging or strangulation [6]. So, Individuals with a first episode of psychotic illness are known to be at high risk of suicide, yet little is understood about the timing of risk in this critical period. Suicide risk was highest in the first month of treatment, decreasing rapidly over the next 6 months and declining slightly thereafter [7]. In this regard, longer duration of untreated psychosis, greater symptoms of depression, and positive symptoms of psychosis were found to increase the odds of experiencing suicidal ideation in first episode psychosis [8]. While according to some studies depressive symptoms during the index psychotic episode and comorbidity with stimulant abuse at baseline were relevant predictive factors for suicidal behavior during the first years of first affective and nonaffective psychotic episodes [9], more depressive symptoms, higher insight, and negative beliefs about psychosis increase the risk for suicidality in FEP [10]. Impulsive behavior such as self-harm, as well as having a family history of severe mental disorder or substance use, have been stated asimportant risk factors for suicide in FEP [11,12]. Furthermore, low levels of cholesterol have been described in suicide behavior including among those individuals who have an increased tendency for impulsivity [13,14]. While, as a kind of psychological explanation, some scholars believe that young men in the early stages of their treatment are seeking to find meaning for frightening, intrusive experiences with origins which often precede psychosis, and these experiences invade personal identity, interactions and recovery [15], some suggests that personality characters, specifically, passive-dependent traits can be a predictor of first suicide attempts FEP [16]. On the other hand, no general agreement regarding higher prevalence of suicide in FEP is so far achievable. For example, while researchers like Nordentoft et al. [17], Bornheimer LA [8], Fedyszyn et al. [7], and Cohen et al. [18] have stated that FEP is a particularly high-risk period for suicide, with a risk as high as 10-60% during the first year of treatment, other scholars like Preti et al. [19], Pompili et al. [20], Crumlish et al. [21], and Addington et al. [22] have expected a lower risk or stated that suicide rates are difficult to measure in FEP patients, even in carefully defined samples. In the present study, suicides and suicide attempts among child and adolescent psychiatric in-patients, during the last five years, in Razi psychiatric hospital, as the largest national psychiatric hospital in Iran and region, has been evaluated to assess the general profile of suicidal behavior among native child and adolescent psychiatric inpatients, and comparing first admission with recurrent admission patients.

Methods

Child and adolescent section of the Razi psychiatric hospital was the filed of the present assessment. For valuation, all inpatients with suicidal behavior (successful suicide and attempted suicide, in total), during the last sixty months, had been included in the current retrospective study. Besides, clinical diagnosis was based on Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th edition (DSM-5) [23].

Statistical Analyses

Difference of suicidal behavior between first admission and recurrent admission patients, had been analyzed by ‘comparison of proportions. Statistical significance as well, had been defined as p value ≤0.05. MedCalc Statistical Software version 15.2 was used as statistical software tool for analysis.

Results

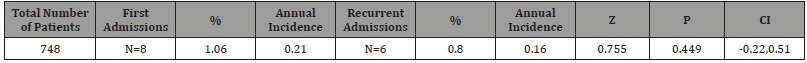

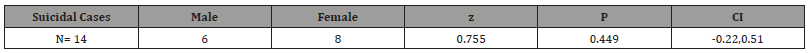

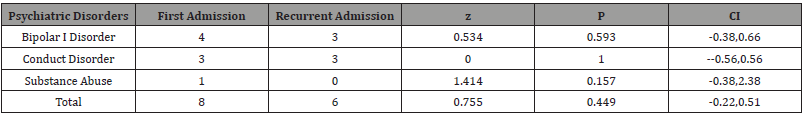

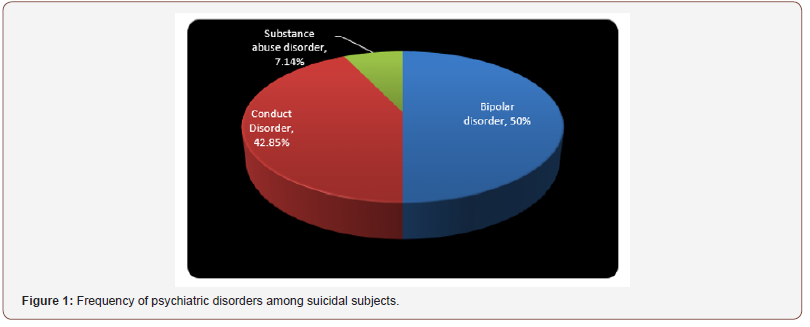

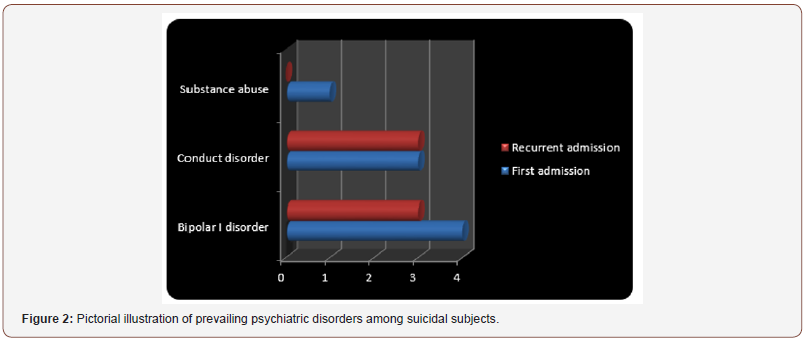

As said by the results, among 748 child and adolescent psychiatric patients hospitalized in razi psychiatric hospital, during a sixty months period (2013-2018), 14 suicide attempts, without any successful one, had been recorded by the security board of hospital (Table 1). Six of suicide subjects were male and 8 of them were female, with no significant difference with regard to quantity (Table 2). The most frequent mental illness was bipolar I disorder (50%), which was significantly more prevalent among female patients (z=2.72, p<0.007, CI 95%:0.19, 1.23), followed by conduct disorder (42.85%), and substance abuse disorder (7.14%) (Figure1). In this regard, no significant difference was evident between the first two primary psychiatric disorders (Table 3). Moreover, no significant difference was evident between the first admission and recurrent admission child and adolescent inpatients, totally (p<0.44) and separately (Table 3 & Figure 2). The annual incidences of suicidal behavior in both groups were comparable, and they were around 0.21% and 0.16%, in first admission and recurrent admission psychiatric inpatients, respectively (Table 1). While self-mutilation, self-poisoning and hanging were the preferred methods of suicide among 60%, 20% and 20% of cases, respectively, with no quantitatively significant difference among them, the first style was significantly more prevalent among female subjects in comparison with male subjects (Z= 1.96 , P< 0.02, CI: -1.23,-0.10) (Table 1 to 3 and Figure 1 & 2).

Table 1: Comparing suicidal behavior between first admission and recurrent admission child and adolescents psychiatric patients in Razi psychiatric hospital thru 2013-2018.

Table 2: Gender difference in child and adolescent suicidal behavior.

Table 3: Frequency of psychiatric disorders among child and adolescent suicidal patients.

Discussion

Suicidal behavior is the most common reason for an emergency evaluation in adolescents. Despite the minimal risk for a complete suicide in a child less than 12 years of age, suicidal ideation or behavior in a child of any age must be carefully evaluated, with particular attention to the psychiatric status of the child and the ability of the family or the guardians to provide the appropriate supervision. The assessment must determine the circumstances of the suicidal ideation or behavior, its lethality, and the persistence of the suicidal intention. An evaluation of the family’s sensitivity supportiveness, and competence must be done to assess their ability to monitor the child’s suicidal potential [24]. Also, the most important risk factors for late school-age children and adolescents, as established by scientific research in this domain were: mental disorders, previous suicide attempts, specific personality characteristics, genetic loading and family processes in combination with triggering psychosocial stressors, exposure to inspiring models and availability of means of committing suicide [25]. In addition, violent method and mental disorder increase the 1-year suicide risk in young male self-harm patients. Further, violent method increases suicide risk within 1 year in all age and gender groups except the youngest females. Repeated self-harm may increase the long-term risk more in young patients. These aspects should be accounted for in clinical suicide risk assessment [26]. So, clinicians should consider the substantially increased risk of suicide among self-harm patients with psychotic disorders [27].

As suicide is a relatively rare event in psychotic disorders, general population-based prevention strategies may have more impact in this vulnerable group as well as the wider population [28, 29]. While the immediate post-discharge period is a time of marked risk, rates of suicide remain high for many years after discharge and patients admitted because of suicidal ideas or behaviors and those in the first months after discharge should be a particular focus of concern [30]. Back to our discussion and according to the findings of the present study, the most common principal diagnoses among the suicide subjects were bipolar disorder and conduct disorder, which was somewhat similar to the findings of Pelkonen et al. [2], since there was no subject with diagnosis of schizophrenia and a remarkable number with diagnosis of conduct disorder in our study, which was not evident in the above survey. Also our results were in harmony with the conclusions of Berkol et al. with respect to higher prevalence of female gender in bipolar patients with suicide attempts [31]. Also, in keeping with the results, while the annual incidences of suicidal behavior in both groups were comparable, they were lower than assessments of Jarbin et al. [3]and Fedyszyn et al.[6], and higher than approximations of Li et al. [32], which could be stemmed from cultural, instrumental, diagnostic and methodical differences. Also, in accordance with the outcomes of the present assessment, no significant difference was evident between the first admission and recurrent admission inpatients, totally and separately, particularly with respect to psychotic disorders. Such an outcome is clearly incongruous with the findings of Nordentoft et al. [17], Bornheimer LA [8], Fedyszyn et al. [7], and Cohenet al. [18] who have stated that first episode psychosis is a particularly high-risk period for suicide and first-episode psychotic disorder , in general, has seemed to be a high-risk population for suicidal behavior during the first year of treatment. On the other hand, our findings are compatible with the stances of Preti et al. [19], Pompili et al. [20], Crumlish et al. [21], and Addington et al. [22], who have estimated a lower risk or indicated that suicide rates are difficult to measure in FEP patients, and there is relatively little specific information about the risk of suicide at illness onset or retrospectively concerning the untreated psychotic period. Anyhow, disregard to outcomes of the present study and its similarities or differences with comparable studies, elements of an inclusive prevention policy can be grouped under five items: securing the hospital environment, optimization of the care of the patients at suicidal risk, training of the medical teams in the detection of the risk and in the care of the suicidal subjects, involvement of the families in the care and implementation of postevent procedures following a completed suicide or an attempt [33]. Also, to reduce the number of suicide attempts among individuals treated for FEP, psychiatric services could consider: restricting the amount of medication prescribed per purchase; individualized suicide risk management plans for all newly admitted patients, including those who do not appear to be at risk; stringent reviews of inpatient psychiatric units for potential ligature points; providing information and psycho-education for significant others in recognition and response to suicide risk; fostering patients’ problem solving and conflict resolution skills; and regular risk assessment and close monitoring of patients, particularly during the high risk period of 3 months after a suicide attempt [17]. Also, along with enhancement of insight, coping strategies should be boosted with a goal of minimizing depression and preventing suicidality [34]. Absence of post- discharge following program, deficiency of documented data regarding the suicidal behavior or its idea before admission, were among the weaknesses of the present assessment. In spite of remarkable findings of the current study, more methodical and comprehensive investigations in future, with taking into account the above shortages, can improve the quality and amendment of mental health services for proper response to patients’ unavoidable problems.

Conclusion

While in the present study the suicidal behavior was nonsignificantly more evident in bipolar disorder in comparison with other psychiatric disorders, no significant difference was evident between first admission and recurrent admission child and adolescent psychiatric inpatients.

Acknowledgement

None.

Conflict of Interest

No conflict of interest.

References

- Fleischmann A, Bertolote JM, Belfer M, Beautrais A (2005) Completed suicide and psychiatric diagnoses in young people: a critical examination of the evidence. Am J Orthopsychiatry 75(4): 676-683.

- Pelkonen M, Marttunen M (2003) Child and adolescent suicide: epidemiology, risk factors, and approaches to prevention. Paediatr Drugs 5(4): 243-265.

- Jarbin H, Von Knorring AL (2004) Suicide and suicide attempts in adolescent-onset psychotic disorders. Nord J Psychiatry 58(2):115-123.

- Apter A, Gvion Y (2016) Adolescent suicide and attempted suicide. In: Wasserman D, ed. Suicide: An Unnecessary Death. (2nd edn) Oxford University Press, London, UK.

- Robinson J, Harris M, Cotton S, Hughes A, Conus P, et al. (2010) Sudden death among young people with first-episode psychosis: An 8-10-year follow-up study. Psychiatry Res 177(3): 305-308.

- Fedyszyn IE, Harris MG, Robinson J, Edwards J, Paxton SJ (2011) Characteristics of suicide attempts in young people undergoing treatment for first episode psychosis. Aust N Z J Psychiatry 45(10): 838- 845.

- Fedyszyn IE, Robinson J, Matyas T, Harris MG, Paxton SJ (2010) Temporal pattern of suicide risk in young individuals with early psychosis. Psychiatry Res 175(1-2): 98-103.

- Bornheimer LA (2018) Suicidal Ideation in First-Episode Psychosis (FEP): Examination of Symptoms of Depression and Psychosis Among Individuals in an Early Phase of Treatment. Suicide Life Threat Behav 49(2): 423-431.

- González-Pinto A, Aldama A, González C, Mosquera F, Arrasate M, et al. (2007) Predictors of suicide in first-episode affective and nonaffective psychotic inpatients: five-year follow-up of patients from a catchment area in Vitoria, Spain. J Clin Psychiatry 68(2): 242-247.

- Barrett EA, Sundet K, Faerden A, Agartz I, Bratlien U, et al. (2010) Suicidality in first episode psychosis is associated with insight and negative beliefs about psychosis. Schizophr Res 123(2-3): 257-262.

- Björkenstam C, Björkenstam E, Hjern A, Bodén R, Reutfors J (2014) Suicide in first episode psychosis: a nationwide cohort study. Schizophr Res 157(1-3): 1-7.

- Beckman K, Mittendorfer-Rutz E, Lichtenstein P, Larsson H, Almqvist C, et al. (2016) Runeson B, Dahlin M. Mental illness and suicide after selfharm among young adults: long-term follow-up of self-harm patients, admitted to hospital care, in a national cohort. Psychol Med 46(16): 3397-3405.

- Shrivastava A, Johnston M, Campbell R, De Sousa A, Shah N (2017) Serum cholesterol and Suicide in first episode psychosis: A preliminary study. Indian J Psychiatry 59(4): 478-482

- Ayesa-Arriola R, Canal Rivero M, Delgado-Alvarado M, Setién-Suero E, González-Gómez J, et al. (2018) Low-density lipoprotein cholesterol and suicidal behaviour in a large sample of first-episode psychosis patients. World J Biol Psychiatry 19(sup3): 158-161.

- Gajwani R, Larkin M, Jackson C(2018) “What is the point of life?”: An interpretative phenomenological analysis of suicide in young men with first-episode psychosis. Early Interv Psychiatry 12(6): 1120-1127.

- Canal-Rivero M, Barrigón ML, Perona-Garcelán S, Rodriguez-Testal JF, Giner L, et al. (2016) One-year follow-up study of first suicide attempts in first episode psychosis: Personality traits and temporal pattern. Compr Psychiatry 71: 121-129.

- Nordentoft M, Madsen T, Fedyszyn I(2015) Suicidal behavior and mortality in first-episode psychosis. J Nerv Ment Dis 203(5): 387-392.

- Cohen S, Lavelle J, Rich CL, Bromet E (1994) Rates and correlates of suicide attempts in first-admission psychotic patients. Acta Psychiatr Scand 90(3): 167-171.

- Preti A, Meneghelli A, Pisano A, Cocchi A, Programma 2000 Team (2009) Risk of suicide and suicidal ideation in psychosis: results from an Italian multi-modal pilot program on early intervention in psychosis. Schizophr Res 113(2-3): 145-150.

- Pompili M, Serafini G, Innamorati M, Lester D, Shrivastava A, et al. (2011) Suicide risk in first episode psychosis: a selective review of the current literature. Schizophr Res 129(1): 1-11.

- Crumlish N, Whitty P, Kamali M, Clarke M, Browne S, et al. (2005) Early insight predicts depression and attempted suicide after 4 years in firstepisodeschizophrenia and schizophreniform disorder. Acta Psychiatr Scand 112(6): 449-455.

- Addington J, Williams J, Young J, Addington D(2004) Suicidal behaviour in early psychosis. Acta Psychiatr Scand 109(2): 116-120.

- American Psychiatric Association (APA) (2013) Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (5th edn). Washington, DC, USA, pp.31-715.

- Nordentoft M, Mortensen PB, Pedersen CB (2011) Absolute risk of suicide after first hospital contact in mental disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry 68 (10): 1058-1064.

- Bilsen J (2018) Suicide and Youth: Risk Factors. Front Psychiatry 9: 540.

- Tidemalm D, Beckman K, Dahlin M, Vaez M, Lichtenstein P, et al. (2015) Age-specific suicide mortality following non-fatal self-harm: national cohort study in Sweden. Psychol Med 45(8): 1699-1707.

- Beckman K, Mittendorfer-Rutz E, Lichtenstein P, Larsson H, Almqvist C, et al. (2016) Mental illness and suicide after self-harm among young adults: long-term follow-up of self-harm patients, admitted to hospital care, in a national cohort. Psychol Med 46(16): 3397-3405.

- Dutta R, Murray RM, Allardyce J, Jones PB, Boydell J (2011) Early risk factors for suicide in an epidemiological first episode psychosis cohort. Schizophr Res 126(1-3): 11-19.

- Dutta R, Murray RM, Hotopf M, Allardyce J, Jones PB, et al. (2010) Reassessing the long-term risk of suicide after a first episode of psychosis. Arch Gen Psychiatry 67(12): 1230-1237.

- Chung DT, Ryan CJ, Hadzi-Pavlovic D, Singh SP, Stanton C, et al. (2017) Suicide Rates After Discharge from Psychiatric Facilities: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. JAMA Psychiatry 74(7): 694-702.

- Berkol TD, İslam S, Kırlı E, Pınarbaşı R, Özyıldırım İ (2016) Suicide attempts and clinical features of bipolar patients. Saudi Med J 37(6): 662-667.

- Li J, Ran MS, Hao Y, Zhao Z, Guo Y, et al. (2008) Inpatient suicide in a Chinese psychiatric hospital. Suicide Life Threat Behav 38(4): 449-455.

- Martelli C, Awad H, Hardy P(2010)[In-patients suicide: epidemiology and prevention]. Encephale 36(2): 83-91.

- Flanagan P, Compton MT (2012) A comparison of correlates of suicidal ideation prior to initial hospitalization for first-episode psychosis with prior research on correlates of suicide attempts prior to initial treatment seeking. Early Interv Psychiatry 6(2): 138-144.

-

Saeed Shoja Shafti, Alireza Memarie, Masomeh Rezaie, Masomeh Hamidi. A Preliminary Survey Regarding Suicidal Conduct among Iranian Juvenile Psychiatric Inpatients. Arch Neurol & Neurosci. 3(5): 2019. ANN.MS.ID.000571.

-

Suicidal Conduct, Psychiatric Inpatients, Suicidal behavior, Preliminary Survey, Psychosis, Adolescent psychiatric, Bipolarc, Psychiatric disorders, Child and adolescent; Psychiatric disorders; Suicide; Suicide attempt; First admission; Recurrent admission; Bipolar disorder; Conduct disorder; Substance Abuse disorder

-

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.