Research Article

Research Article

Distribution of Hematological Parameters Counts for Children with Leukemia in Children’s Cancer Units at Al-Kuwait Hospital, Sana’a City: A Cross-Sectional Study

Lutfi AS Al-Maktari1, Mohamed AK Al-Nuzaili1, Hassan A Al-Shamahy2*, Abdulrahman A Al-Hadi3,Abdulrahman A Ishak3 and Saleh A Bamashmoos1

1Department of Hematology, Faculty of Medicine and Health Sciences, Sana’a University, Republic of Yemen

2Department of Medical Microbiology and Clinical Immunology Department, Faculty of Medicine and Health Sciences, Sana’a University, Republic of Yemen

3Department of Pediatric, Faculty of Medicine and Health Sciences, Sana’a University, Republic of Yemen

Hassan A Al-Shamahy, Faculty of Medicine and Heath Sciences, Sana’a University, P.O. Box 775 Sana’a, Yemen.

Received Date:June 14, 2021; Published Date: June 30, 2021

Abstract

Introduction and aims: Leukemia is a heterogeneous group of hematological disorders that is made up of several diverse and biologically distinct subgroups. Leukemia is the eleventh and tenth most common cause of cancer morbidity and mortality worldwide, respectively. There are insufficient data on the hematological parameters counts of leukemia in Yemen. This cross-sectional study aims to determine the hematological parameters counts for children with leukemia.

Materials and methods:A cross-sectional study was conducted on children with leukemia who were treated selectively in the pediatric leukemia units of Kuwait University Hospital in Sana’a. Group diagnostics and histopathological diagnoses were formed in line with the French, American and British classifications of leukemia in children in the pediatric leukemia units, over a period of 5 years from January 1, 2014 to December 31, 2018. Hematological Parameters between Types of Leukemia. The distribution of some hematological parameters with respect to leukemia types with reference values of WBC count (3.31-11.62×109/L), platelet counts (145.5-444.5×109/L), neutrophil count (1.01-7.22×109/L), eosinophil count (0.05-1.21×109/L), and basophil count (0.01–0.05 ×109/L) was analyzed and compared with results of non-malignant diseases.

Results: 241 leukemia patients were diagnosed, treated and followed up; there was association of leukemia with younger age group; 50% were in the age group 1-5 years and with mean ± SD age= 6.44 ± 3.7 years. There was significant association with male (66.7%). In Acute leukemia, neutropenia (59.1%) and thrombocytopenia (75.7%) were found, while in chronic leukemia, neutrophilia (0%), basophilia (38.3%), and eosinophilia (5.7%) were recorded. Leukocytosis was observed in all types of leukemia. In other non-malignant diseases: leukopenia 12.2%, leukocytosis 53%, thrombocytopenia (50%), thrombocytosis (9.9%), neutropenia (28%), and neutrophilia (29.3%), basopenia (28.6%), Basophilia (27.9%) and eosinopenia in 39.6% of the patients.

Conclusion: There is significant differences between acute, chronic leukemia and with non-malignant patients. Thus, laboratory professionals, the first who encounter the patients’ results, should perform more laboratory investigation as ,immunophenotyping , cytogenetic and molecular diagnostic for peripheral and bone marrow morphology assessment as a reflex test for those who have abnormal hematological parameters.

.Keywords: Childhood leukemia; Hematological parameters; Yemen

Introduction

Leukemias are a heterogeneous group of hematological malignancies consisting of several diverse and biological types distinct subgroups. It is a clonal tumor of hematopoietic cells caused by arrays of somatic factors mutations in pluripotent stem cells and progenitor cells. The mutated neoplastic cells behave like hematopoietic stem cells in that they can self-replicate, differentiate, and feed the progenitor cells of the different hematopoietic lineages. These unipotently leukemic stem cells can undergo varying degrees of maturation to phenotypic transcription of mature blood cells [1,2]. The precise cause of leukemia is not so far clear. Nevertheless, several factors, mostly heredity, genetic mutations, epigenetic lesions, ionic radiation, other chemical and occupational exposures, therapeutic drugs, smoking, and some viral agents, have been concerned in the development of leukemia [3- 10]. Two types of classification systems for leukemia are commonly used: the French American British (FAB) classification system that relies on morphology and cytochemical staining to identify specific types of leukemia and the World Health Organization (WHO) which reviews classification information, cytomorphology, cytochemistry, and immunophenotyping, cytogenetics, and clinical features for the identification and classification of clinically significant disease entities [11,12]. The French, American, and British leukemia experts separated myeloid leukemia into acute myeloid leukemia (AML-with subtypes, M0 through M7), Chronic Myeloid leukemia (CML), and myelodysplastic syndromes (MDS) based on the type of cell, leukemia develops from and how mature the cells are. This was based mainly on how the leukemia cells looked under the microscope after routine staining and some cytochemical characteristics [11,13,14]. Lymphoid malignancies represent a heterogeneous group of disorders divided into four categories based on the maturity of the neoplastic cells and the distribution of disease as acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL), chronic lymphoblastic leukemia (CLL), malignant lymphoma and plasma cell neoplasms, and hairy cell leukemia [15].

Leukemia is the 8th to 12th most common cancer disease in the globe. It affects all nations and peoples of the world without discrimination based on their sociodemographic background, even though it has a greater risk in urbanized populations [4,16]. Recently in 2021, a hospital-based registry data analysis and estimation is done in Yemen revealed that about 988 childhood leukemia cases had been diagnosed; Acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) was the most common (78.6%), followed by acute myelogenous leukemia (AML) (15.6%), while chronic myelogenous leukemia (CML) (4.5%) and Juvenile myelomonocytic leukemia (JML) (1.2%) were rare. There was association of leukemia with younger age group; 50% were in the age group 1-5 years, and male children; 66.7% [3,4]. The impact of leukemia in developing countries is enormous due to premature death of children, loss of parents, loss of productivity due to a disability, and high medical cost that affects the socioeconomic and health welfare of the population [17-19]. While leukemia is dealt with very well in the developed world, there is little evidence on the current status of the disease in Yemen in general and in the study area in particular. Also, there are insufficient data on the hematological parameters counts of leukemia in Yemen, so this cross-sectional study aims to determine the hematological parameters counts for children with leukemia in the pediatric cancer units of Al-Kuwait Hospital, Sana’a City.

Materials and Methods

A cross-sectional study was conducted on children with leukemia who were treated selectively in the pediatric leukemia units of Al-Kuwait University Hospital in Sana’a. Group diagnostics and histopathological diagnoses were formed in line with the French, American and British classifications of leukemia in children in the pediatric leukemia units, over a period of 5 years from January 1, 2014 to December 31, 2018. Hematological Parameters between Types of Leukemia. The distribution of some hematological parameters with respect to leukemia types with reference values of WBC count (3.31-11.62×109/L), platelet counts (145.5-444.5×109/L), neutrophil count (1.01-7.22 ×109/L), eosinophil count (0.05-1.21×109/L), and basophil count (0.01- 0.05 ×109/L) was analyzed and their proportions were calculated. Sociodemographic information was collected using a pre-tested structured questionnaire. A 4 ml venous blood sample was obtained from each patient for complete blood count (CBC) analysis, peripheral morphology assessment and cytochemical study. Laboratory diagnostic procedures were performed according to standard operating procedures (SOPs) for each test listed (complete blood count - CBC, peripheral morphology examination, and bone marrow aspiration) according to the diagnostic material provider. CBC automation was performed on a Cell-Dyn 3500 hematology analyzer (Abbott Corporation, USA). For patients with lower or higher than the reference interval for RBC count, hemoglobin concentration, WBC count, and platelet count [20], peripheral morphology was examined with Wright’s stain and Sudan Black B (SBB) stain. After peripheral morphology examination, for those patients with suspected leukemia (patients with peripheral blood morphology images showing WBC abnormalities including immature cells, morphological defects, and/or an abnormal reaction to the SBB with erythrocyte abnormalities (abnormal concentration, volume and/or shape of hemoglobin and platelet morphology) a bone marrow aspiration examination using Wright’s stain and Sudan black B stain was performed to confirm and classify the specific leukemia group. Sudan Black B stain was used to distinguish myeloid from lymphoid cell lineages in acute leukemia patients by examining the presence of black granular staining granules in the myeloid cell lineage while lymphocytes do not pigment. Data outputs are shown with tables.

Ethical Approval

Ethical approval was obtained from the Medical Research & Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Medicine and Health Sciences, Sana’a University. All data, including patient identification were kept confidential.

Results

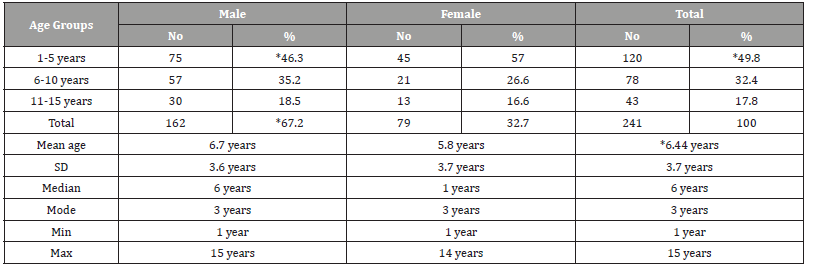

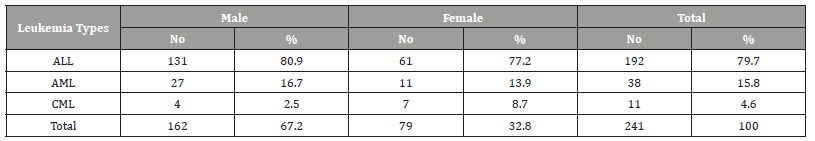

(Table 1) Table 1 shows the age and gender distribution of children with childhood leukemia. The mean ± SD age of all cases was 6.44±3.7 years. Most of the cases were in the age group 1-5 years (49.8%), followed by the age group 6-10 years (32.4%), while only 17.8% of the cases were in the age group 11-15 years (disease decreases with increasing age). As for gender, most of the cases were males (67.2%), while the percentage of females was 32.7% (male to female ratio=2-1). Acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) was the most common (79.7%), followed by acute myelogenous leukemia (AML) (15.8%), while chronic myelogenous leukemia (CML) were (4.6%) (Table 2).

Table 1:Age and gender distribution of children with childhood leukemia in Sana’a, Yemen.

Table 2:Distribution of leukemia types among children suffering from childhood leukemia in Sana’a, Yemen.

ALL = Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia, AML= Acute Myelogenous Leukemia, CML= Chronic Myelogenous Leukemia/

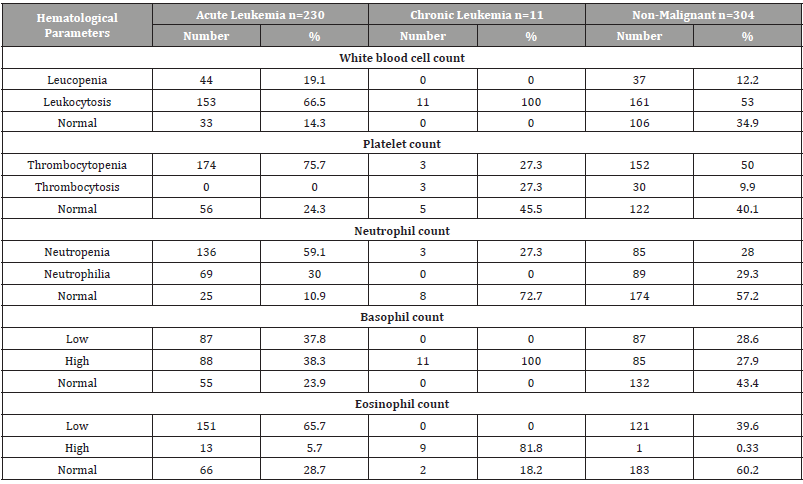

Hematological parameters between leukemia types and other non-malignant diseases were analyzed and their proportions were calculated. In acute leukemia: leukopenia 19.1%, leukocytosis 66.5% while 14.3% were normal for white blood counts in patients with acute leukemia. For platelet counts, 75.7% had thrombocytopenia, thrombocytosis was zero, while 24.3% had a normal platelet count. Also, neutropenia occurred in 59.1%, and neutrophilia in 30%. Basopenia (or basocytopenia) occurred in 37.8% of patients and Basophilia in 38.3%. Eosinopenia in 65.7% and Eosinophilia in 5.7%. In chronic leukemia: leukopenia was 0%, and all patients were leukocytosis (100% ). For platelet counts, 27.3% had thrombocytopenia, and thrombocytosis was 27.3%, while 45.5% had a normal platelet count. Also, neutropenia occurred in 27.3%, and neutrophilia in 0%. Basopenia was 0% and all patient showed Basophilia. Also 81.8% of chronic leukemia had Eosinophilia. In other non-malignant diseases: leukopenia 12.2%, leukocytosis 53% while 34.9% were normal for white blood counts in patients with other non-malignant diseases. For platelet counts, 50% had thrombocytopenia, thrombocytosis was 9.9%, while 40.1% had a normal platelet count. Also, neutropenia occurred in 28%, and neutrophilia in 29.3%. Basopenia (or basocytopenia) occurred in 28.6% of patients and Basophilia in 27.9%. Eosinopenia in 39.6% and Eosinophilia only in 0.33% (Table 3).

Table 3:Distribution of hematological parameter counts for children with childhood leukemia in Sana’a, Yemen.

ALL = Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia, AML= Acute Myelogenous Leukemia, CML= Chronic Myelogenous Leukemia

Discussion

Regarding the distribution of some hematological variables with types of leukemia. In acute leukemia, neutropenia (59.1%) and thrombocytopenia (75.7%) were found, while in chronic leukemia, neutropenia (0%), basophilia (100.0%), and eosinophilia (81.8%) were observed. This finding is supporting the biological process that in acute leukemia, due to infiltration of immature malignant cells in the bone marrow and arrest of maturation, there will be neutropenia, anemia and thrombocytopenia in the peripheral circulation [21,22]. On the other hand, chronic leukemia is characterized by significantly increased bone marrow activity, which leads to an increase in the number of white blood cells in the bone marrow as well as in the circulatory system, as well as in chronic lymphocytic leukemia in the lymph nodes. In chronic myeloid leukemia, morphologically and functionally normal granules are present, consisting predominantly of neutrophils and myeloid cells. Basophil leukocytosis is a hallmark of chronic myeloid leukemia, although eosinophilia is usually present [23]. Leukopenia in the current study occurred in acute leukemia (19.1%) and in non-malignant patients (12.2%). In patients without leukemia in the current study, leukopenia may be due to a viral infection, such as a common cold, influenza, HIV or dengue viruses, or bacterial infections as a typhoid, malaria, tuberculosis, and rickettsial infections [24]. It has also been associated with chemotherapy, radiotherapy, myelofibrosis, aplastic anemia, stem cell transplantation, bone marrow transplantation, and steroid use [25]. It has also been proven that it is caused by a deficiency in certain minerals, such as copper and zinc [26].

Neutropenia in the current study occurred more frequently in patients with acute leukemia (59.1%) and less frequently in chronic leukemia (27.3%) and the non-malignant group (28%). Neutrophils constitute the majority of circulating white blood cells and serve as a primary defense against infection by destroying bacteria, bacterial fragments, and immunoglobulin-bound viruses in the blood [27]. People with neutropenia are more susceptible to bacterial infections, and without immediate medical care, the condition may become life-threatening (neutropenic sepsis). It is also known that mortality increases during leukemia treatment if neutropenia is also present [28]. Therefore, when combined with profound neutropenia (febrile neutropenia), it is considered a medical emergency and requires broad-spectrum antibiotics. An absolute neutrophil count of less than 200 is considered a medical emergency and almost always requires hospitalization and initiation of extensive antibiotics with selection of specific antibiotics based on local resistance patterns [25]. Precautions to avoid opportunistic infections in people with chronic neutropenia include maintaining hand hygiene with soap and water, good dental hygiene and avoiding highly contaminated sources that may contain large fungal reservoirs such as mulches, construction sites, and bird or other animal waste [25] on the other hand, the effectiveness of blood transfusions has not been proven [29]. Neutrophilia in the current study occurred equally in patients with acute leukemia (30%) and the non-malignant group (29.3%), while no case of chronic leukemia was found. Neutrophils are the primary white blood cells that respond to a bacterial infection, so the most common cause of neutrophilia is bacterial infection, especially pyogenic infection [30]. Neutrophils are also increased in any acute inflammation, so they will rise after an infarction heart attack or burns [30]. Neutrophilia may also be the result of metastasis. Despite the fact that CML (chronic myeloid leukemia) is a disease in which blood cells multiply out of control, no cases of neutrophilia were found among 11 patients with CML in the current study. Neutrophilia can also be caused by appendicitis and splenectomy; and can be a consequence of leukocyte adhesion deficiency [31,32].

Leukocytosis in the current study occurred in 66.5% of patients with acute leukemia and 100% in patients with chronic leukemia and the non-malignant group was 53%, leukocytosis often a sign of an inflammatory response mostly as a result of infection, but it may occur also after some parasitic infections or bone tumors as well as leukemia. It may also occur after strenuous exercise, convulsions such as epilepsy, emotional stress, pregnancy and childbirth, anesthesia, as a side effect of medications (eg lithium), and administration of epinephrine [33]. This increase in the number of leukocytes (primarily neutrophils) is regularly accompanied by a ‘ left upper shift’ in the ratio of immature to mature neutrophils and macrophages. The proportion of immature leukocytes increases due to the proliferation and inhibition of monocyte and granulocyte precursors in the bone marrow that are stimulated by several products of inflammation including C3a and G-CSF. Although it may indicate disease, leukocytosis is considered a laboratory finding rather than a separate disease. This classification is similar to that of a fever, which is also a test result rather than a disease. A ‘Right shift’ in the ratio of immature to mature neutrophils is considered with a decrease or deficiency of ‘young neutrophils’ (metamyelocytes, band neutrophils) in the blood smear, associated with the presence of ‘giant neutrophils’. This fact shows suppression of bone marrow activity, as a hematological marker specific for pernicious anemia and radiation sickness [34]. A white blood cell count higher than 25 to 30 x 109/L is called a leukemoid reaction, which is the reaction of healthy bone marrow to severe stress, trauma, or infection. It differs from leukemia and from leukoerythroblastosis, in which immature white blood cells (acute leukemia) or mature, but nonfunctional white blood cells (chronic leukemia) are found in the peripheral blood [34].

Basophilia in the current study occurred in 38.3% of acute leukemic patients and 100% in chronic leukemia patients and in the non-malignant group it was 27.9%. Basophilia is the condition of more than 200 basophils/μl in the venous blood. Basophils are the least numerous of the myelogenous cell, and it is rare for their numbers to be abnormally high without a change in other components of the blood. Alternatively, basophilia is often associated with other white blood cell conditions such as eosinophilia. Basophils are easily identifiable by blue staining of the granules within each cell, marked as granules, as well as segmented nuclei [35,36]. Basophilia can be attributed to many causes and is usually not sufficient evidence alone to indicate a specific condition when isolated as a finding under microscopy. In combination with other findings, such as abnormal levels of neutrophils, it may indicate the need for further work. For example, additional evidence of left-shifted neutrophilia combined with basophilia points to a possible possibility primarily for chronic myeloid leukemia (CML), or an alternative myeloproliferative neoplasm. In addition, the basophilia in the presence of numerous circulating blasts indicates the possibility of acute myeloid leukemia. Elevated basophils may also be representative of many other primary neoplasms such as polycythemia vera (PV), myelofibrosis, thrombocythemia or, in rare cases, solid tumors. Alternative root causes other than these neoplastic complications are most commonly allergic reactions or chronic inflammation associated with infections such as tuberculosis, influenza, inflammatory bowel disorder or inflammatory autoimmune disease [35]. Chronic hemolytic anemia and infectious diseases such as smallpox also show elevated levels of basophils [37]. Use of certain medications and food intake can also be associated with basophilia symptoms [38].

Eosinophilia in the current study occurred in only 5.7% of patients with acute leukemia, 81.8% in patients with chronic leukemia and in the non-malignant group it was only 0.33%. Eosinophilia is a condition in which the number of eosinophils in the peripheral blood exceeds 5x108/L (500/μL) [39]. Hypereosinophilia is an individual’s blood eosinophil count above 1.5 x 109/L (i.e. 1500/μL). Hypereosinophilic syndrome is a sustained elevation of this number above 1.5 x 109/l (i.e. 1500/μl) which is also associated with evidence of eosinophilbased tissue injury. Chronic eosinophilic leukemia not otherwise specified (eg CEL, NOS), is a leukemic disorder of the eosinophil cell lineage that causes eosinophil blood counts greater than 1500/ μL. The latest WHO criteria specifically exclude from this disorder the hypereosinophilia/eosinophilia associated with BCR-ABL1 fusion gene-positive chronic myeloid leukemia, polycythemia vera, essential thrombocytosis, primary myelofibrosis, chronic neutrophilic leukemia, chronic myelomonocytic leukemia, atypical chronic myelogenous leukemia, clonal eosinophilias involving gene rearrangements of PDGFRA, PDGFRB, or FGFR1, and chromosome translocations that form PCM1-JAK2, ETV6-JAK2, or BCR-JAK2 fusion genes. For this diagnosis, the immature (eg, myeloblastic) eosinophil cell counts in the bone marrow and peripheral blood must be less than 20% and the chromosomal changes (inv(16) (p. 13.1 q 22)) and t (16;16) (p 13;q22) ) in addition to other features of the diagnosis of acute myelogenous leukemia should be absent. Latter diagnostic features include clonal cytogenetic abnormalities and molecular genetic abnormalities diagnostic for other forms of leukemia or presence of greater numbers of myeloblasts of 55% in the bone marrow or 2% in the blood. Chronic eosinophilic leukemia may transform into acute eosinophilia or other acute myelogenous leukemia [40,41].

Conclusion

There is significant differences between acute, chronic leukemia and with non-malignant patients. Thus, laboratory professionals, the first who encounter the patients’ results, should perform more laboratory investigation as, immunophenotyping, cytogenetic and molecular diagnostic for peripheral and bone marrow morphology assessment as a reflex test for those who have abnormal hematological parameters. The prevalence of leukemia among patients who have abnormal hematological parameters in the pediatric cancer units of Al-Kuwait Hospital, Sana’a City is significant which needs further comprehensive investigations of the associated factors and predictors with more up to date diagnostic methods.

Author’s Contribution

The first author presented the data and the first, second and the third authors analyzed the data and wrote, revised and edited the paper.

Acknowledgment

Thanks to the Pediatric Leukemia Unit at Kuwait Hospital, specifically to Dr. Abdulrahman Al-Hadi, a human doctor who spends his life, knowledge and time for children who suffer from this malignant disease.

Conflict of Interest

No conflict of interest.

References

- Kulshrestha R, Sah SP (2009) Pattern of occurrence of leukemia at a teaching hospital in eastern region of Nepal: a six-year study. JNMA J Nepal Med Assoc 48(173): 35-40.

- Landau DA, Carter SL, Getz G, Wu CJ (2014) Clonal evolution in hematological malignancies and therapeutic implications. Leukemia 28(1): 34-43.

- El-Zine MAY, Alhadi AM, Ishak AA, Al-Shamahy HA (2021) Prevalence of Different Types of Leukemia and Associated Factors among Children with Leukemia in Children’s Cancer Units at Al-Kuwait Hospital, Sana’a City: A Cross- Sectional Study. Glob J Ped and Neonatol Car 3(4): 1-5.

- Alhadi AM, El-Zine M AY, Ishak AA, Al-Shamahy HA (2021) Childhood Leukemia in Yemen: The Main Types of Childhood Leukemia, its Signs and Clinical Outcomes. EC Pediatrics 10 (6): 75-82.

- Whitehead TP, Metayer C, Wiemels JL, Singer AW, Miller MD (2016) Childhood leukemia and primary prevention. Curr Probl Pediatr Adolesc Health Care 46(10): 317-352.

- Deschler B, Lubbert M (2006) Acute myeloid leukemia: epidemiology and etiology. Cancer 107(9): 2099-2107.

- Pyatt D, Hays S (2010) A review of the potential association between childhood leukemia and benzene. Chem Biol Interact 184(1-2): 151-164.

- Pyatt D (2004) Benzene and hematopoietic malignancies. Clin Occup Environ Med 4(3): 529-555.

- Sandler DP, Shore DL, Anderson JR, FR Davey, D Arthur, et al. (1993) Cigarette smoking and risk of acute leukemia: associations with morphology and cytogenetic abnormalities in bone marrow. J Natl Cancer Inst 85(24): 1994-2003.

- Belson M, Kingsley B, Holmes A (2007) Risk factors for acute leukemia in children: a review. Environ Health Perspect 115(1): 138-145.

- JM Bennett, D Catovsky, M T Daniel, G Flandrin, D A Galton, et al. (1976) Proposals for the classification of the acute leukaemias French American- British (FAB) co-operative group. Br J Haematol 33(4): 451-458.

- WHO (2018) The WHO Classification of Tumours series are authoritative and concise. In: Elder DE, Massi D, Scolyer RA, Willemze R (eds.) Formats: Print Book WHO.

- American Cancer Society (2018) Acute Myeloid Leukemia (AML) Subtypes and Prognostic Factors, American Cancer Society Inc, Atlanta, USA.

- Bloomfield CD, Brunning RD (1985) The revised French American-British classification of acute myeloid leukemia: is new better. Ann Intern Med 103(4): 614-620.

- J van Eys, J Pullen, D Head, J Boyett, W Crist, et al. (1986) The French American- British (FAB) classification of leukemia. The pediatric oncology group experience with lymphocytic leukemia. Cancer 57(5): 1046-1051.

- Adalberto MF, Marion P, Jacques F, Isabelle S, Alain E, et al. (2018) Epidemiological patterns of leukaemia in 184 countries: a population-based study. Lancet Haematol 5(1): e14-e24.

- Amer M Zeidan, Dalia Mahmoud, Izabela T Kucmin-Bemelmans, Cathelijne J M Alleman, Marja Hensen, et al. (2016) Economic burden associated with acute myeloid leukemia treatment. Expert Rev Hematol 9(1): 79-89.

- Mutuma J, Wakhungu J, Mutai C (2016) The socio-economic effect of cancer on patients’ livelihoods in Kenyan households. Bibechana 14: 37-41.

- American Cancer Society (2010) The Global Economic Cost of Cancer. American Cancer Society, Atlanta, USA.

- Lealem Gedefaw Bimerew, Tesfaye Demie, Kaleab Eskinder, Aklilu Getachew, Shiferaw Bekele, et al. (2018) Reference intervals for hematology test parameters from apparently healthy individuals in southwest Ethiopia. SAGE Open Med 6: 1-5.

- Dohner HD, Weisdorf DJ, Bloomfield CD (2015) Acute myeloid leukemia. New England Journal of Medicine 373(12): 1136-1152.

- Kouchkovsky ID, Abdul-Hay M (2016) Acute myeloid leukemia: a comprehensive review and 2016 update. Blood Cancer 6(7): e441-e446.

- Atsushi Ogasawara, Hiromichi Matsushita, Yumiko Tanaka, Yukari Shirasugi, Kiyoshi Ando, et al. (2019) A simple screening method for the diagnosis of chronic myeloid leukemia using the parameters of a complete blood count and differentials. Clin Chim Acta 489: 249-253.

- Nicholson RJ, Kelly KP, Grant IS (1995) Leucopenia associated with lamotrigine. BMJ 310(6978): 504.

- Newburger PE, Dale DC (2013) Evaluation and management of patients with isolated neutropenia. Semin Hematol 50(3): 198-206.

- Kassahun W, Tesfaye G, Bimerew LG (2020) Prevalence of Leukemia and Associated Factors among Patients with Abnormal Hematological Parameters in Jimma Medical Center, Southwest Ethiopia: A Cross-Sectional Study. Advances in Hematology pp. 1-6.

- National Center for Biotechnology (2015) Neutrophils. National Library of Medicine.

- Fung M, Kim J, Marty FM, Schwarzinger M, Koo S (2015) Meta-Analysis and Cost Comparison of Empirical versus Pre-Emptive Antifungal Strategies in Hematologic Malignancy Patients with High-Risk Febrile Neutropenia. PLOS ONE 10(11): e0140930.

- Ohls, Robin (2021) Hematology, immunology and infectious disease neonatology questions and controversies. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier/Saunders, University of Pittsburgh, USA.

- Mitchell Richard Sheppard, Kumar Vinay, Abbas Abul K, Fausto Nelson (2012) Robbins Basic Pathology. Philadelphia: Saunders.

- (2013) Blood and cancer clinic.

- ISI Mohamed, RJ Wynn, K Cominsky, AM Reynolds, RM Ryan, et al (2006) White blood cell left shift in a neonate: a case of mistaken identity. J Perinatol 26(6): 378-380.

- Rogers, Kara (2011) Leukocytosis definition. Blood: Physiology and Circulation pp. 198.

- Zorc Joseph J (2009) Leukocytosis. Schwartz's Clinical Handbook of Pediatrics (4th), Philadelphia: Wolters Kluwer/Lippincott Williams & Wilkins p.559.

- Sticco Kristin, Lynch David (2019) Basophilia. National Center for Biotechnology Information, U.S. National Library of Medicine, Stat Pearls Publishing, USA.

- Boiten HJ, De Jongh E (2018) Atypical basophilia. Blood 132(5): 551.

- Dilts TJ, McPherson RA (2011) Optimizing Laboratory Workflow and Performance. Henry's Clinical Diagnosis and Management by Laboratory Methods. Elsevier pp. 13-23.

- Valent P, Sotlar K, Blatt K, Hartmann K, Reiter A, et al. (2017) Proposed diagnostic criteria and classification of basophilic leukemias and related disorders. Leukemia 31(4): 788-797.

- (2012) Eosinophilic Disorders. Merck & Co.

- Gotlib J (2017) World Health Organization-defined eosinophilic disorders: 2017 update on diagnosis, risk stratification, and management. Am J Hematol 92(11): 1243-1259.

- Helbig G, Soja A, Bartkowska Chrobok A, Kyrcz Krzemień S (2012) Chronic eosinophilic leukemia-not otherwise specified has a poor prognosis with unresponsiveness to conventional treatment and high risk of acute transformation. Am J Hematol 87(6): 643-645.

-

Lutfi AS Al-Maktari, Mohamed AK Al-Nuzaili, Hassan A Al-Shamahy, Abdulrahman A Al-Hadi, Abdulrahman A Ishak, et al., Distribution of Hematological Parameters Counts for Children with Leukemia in Children’s Cancer Units at Al-Kuwait Hospital, Sana’a City: A Cross-Sectional Study. Adv Can Res & Clinical Imag. 3(2): 2021. ACRCI.MS.ID.000560.

-

Childhood leukemia, Hematological parameters, Yemen, Tumor, Eosinopenia, Basopenia

-

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.