Mini Review

Mini Review

The Resurgence of Mucormycosis in the Covid-19 Era – A Review

Amit Bhardwaj1, Kratika Mishra2*, Shivani Bhardwaj3, Anuj Bhardwaj4

1Department of Orthodontics and Dentofacial Orthopaedics, Modern Dental College and Research Centre, Indore, India

2Department of Orthodontics and Dentofacial Orthopaedics, Index Institute of Dental Sciences, Indore, Madhya Pradesh, India

3Department of Prosthodontics, College of Dental Sciences, Rau, Madhya Pradesh, India

4Department of Conservative Dentistry and Endodontics, College of Dental Sciences, India

Kratika Mishra, Department of Orthodontics and Dentofacial Orthopaedics, Index Institute of Dental Sciences, Indore, Madhya Pradesh, India.

Received Date: June 7, 2021; Published Date:June 25, 2021

Abstract

Mucormycosis (MCM) is a life-threatening infection that carries high mortality rates with devastating disease symptoms and diverse clinical manifestations. This article briefly explains clinical manifestations and risk factors and focuses on putative virulence traits associated with mucormycosis, mainly in the group of diabetic ketoacidotic patients, immunocompromised patients. The diagnosis requires the combination of various clinical data and the isolation in culture of the fungus from clinical samples. Treatment of mucormycosis requires a rapid diagnosis, correction of predisposing factors, surgical resection, debridement and appropriate antifungal therapy. The overall rate of mortality of mucormycosis is approximately 40%.

Keywords:Amphotericin B, emerging, Mucorales, mucormycosis, zygomycetes

Introduction

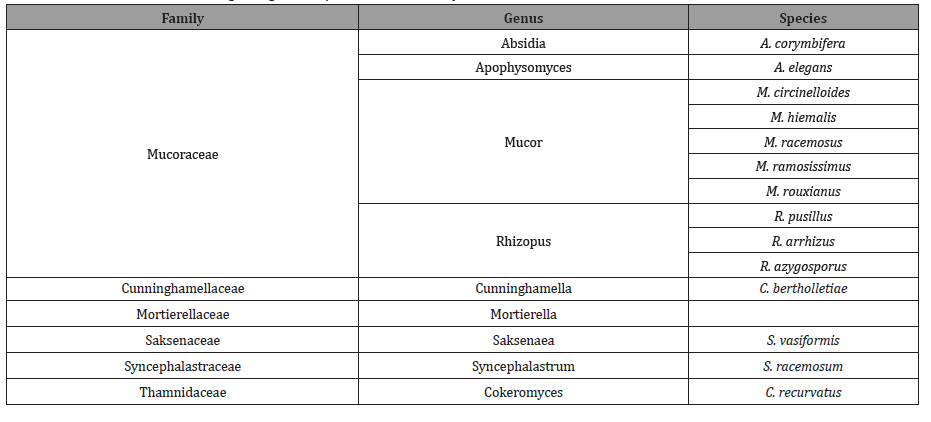

Mucormycosis is defined as an opportunistic infection, affecting patients with diabetes mellitus (DM), neutropenia, malignancy, chronic renal failure, and acquired immunodeficiency syndrome and those who have received organ or hematopoietic stem cell transplants, it can affect immunocompetent hosts as well (such as trauma patients) [1,2]. It is third invasive mycosis after candidiasis and aspergillosis which is caused by several species of different genera [3] (Table 1).

Table 1: Classification of the aetiological agents responsible for mucormycosis.

This mucormycosis infection is caused by Mucorales. Zygomycetes is the class that is divided into two orders i.e., mucorales and entomophthorales. Mucormycosis is a fulminant disease with high rates of mortality and morbidity that mainly affects the immunocompromised patients.

This disease is characterised by host tissue infarction and necrosis. Tissue necrosis due to blood vessels invasion and subsequent thrombosis are the hallmarks of invasive mucormycosis. In a French study, mucormycosis incidence increased by 7.3% per year in neutopenic patients [4].

Routes of Transmission

The most common route of transmission is inhalation of spongiosprores. Other routes are direct implantation into injured skin like burns, intra-venous drugs administration, exposure or trauma with contaminated soil. It is rapid progressive disease extending into neighbouring tissues, including orbit and brain involvement in more severe cases.

Classification of Mucormycosis is based on the involvement of anatomic sites of infection reflecting in part the portals of their entrance in the humans. The spores enter through different routes of transmission the disease may present as rhino-orbitalcerebral, pulmonary, cutaneous, subcutaneous, gastrointestinal and disseminated form [5,6].

Discussion

The mortality rate of mucormycosis is approximately 40%, but this rate depends on the clinical presentation of the disease, the underlying disease, surgery, and the extent of the infection [7,8,9,10].

Mucormycosis occurs in patients with diabetes mellitus and ketoacidosis, haematological malignancies [11,12,13,14] like neutropenia [12,15] or graft vs. host disease, in solid-organ transplant patients [11,19,20,18–33] and in patients receiving high doses of corticosteroids [34].It is infrequent in immunocompetent patients like those patients that are without any risk factors,HIVinfected patients and patients with solid organ tumors [35,36].

Mucormycosis most commonly occurs in the sinuses (39%), lungs (24%), skin (19%), brain (9%), and gastrointestinal tract (7%), in the form of disseminated disease (6%), and in other sites (6%) [37]. With the exception of rhino-cerebral and cutaneous mucormycosis, the clinical diagnosis of mucormycosis is difficult, and is often made at a late stage of the disease or post-mortem [38].

Diagnosis includes tests using cultures of clinical samples, sputum analysis, histopathological testing and it requires the combination of various clinical data and the isolation in culture of the fungus from clinical samples. Other techniques involve computed tomography scans, magnetic resonance imaging. Magnetic resonance imaging is technique of choice when intracranial structures are affected. Molecular biology advances would greatly improve diagnosis in such deadly disease.

Treatment depends on early diagnosis, correction of predisposing factors, anti fungal therapy, surgical debridement and resection. Patients with diabetic ketoacidosis should be addressed and suppression of corticosteroids should be done. The best treatment of mucormycosis is rapid and complete surgery. Surgery combined with use of antifungal therapy is best choice of treatment [39,40,41]. Current studies suggest that point to high dose liposomal amphotericin B has shown variable activity in vitro against agents responsible for mucormycosis. Other drugs of choice includes itraconazole, voriconazole, posaconaazole, ravuconazole [42]. Other therapeutic alternatives include cytokines such as gamma interferons or granulocyte-macrophage colony stimulating factors for treatment of mucormycosis [43,44].

Conclusion

This life-threatening fungal infection is characterised by host tissue infarction and necrosis that occurs in immunocompromised patients with high rates of mortality. Further studies are required to analyse and better optimise induction and consolidation treatment. The clinical outcomes of patients with mucormycosis are poor especially in patients with uncontrolled diabetes and age is negative prognostic factors.

Acknowledgement

None.

Conflicts of Interest

No Conflicts of Interest.

References

- B Spellberg, TJ Walsh, DP Kontoyiannis, JJ Edwards Jr, AS Ibrahim (2009) Recent advances in the management of mucormycosis: from bench to bedside. Clin Infect Dis 48(12): 1743-1751.

- SR Sridhara, G Paragache, NK Panda, A Chakrabarti (2005) Mucormycosis in immunocompetent individuals: an increasing trend. J Otolaryngol 34(6): 402-406.

- Bouza E, Munoz P, Guinea J (2006) Mucormycosis: an emerging disease? Clinical Microbiology and Infection 12(7): 7-23.

- Guinea J, Escribano P, Vena A, Patricia Muñoz, María Del Carmen Martínez-Jiménez, et al. (2017) Increasing incidence of mucormycosis in a large Spanish hospital from 2007 to 2015: Epidemiology and microbiological characterization of the isolates. PLoS One 12(6): e0179136.

- Sun HY, Singh N (2011) Mucormycosis: its contemporary face and management strategies. Lancet Infect Dis 11(4): 301-311.

- Spellberg B, Edwards J Jr, Ibrahim A (2005) Novel perspectives on mucormycosis: pathophysiology, presentation, and management. Clin Microbiol Rev 18(3): 556-569.

- Petrikkos G, Skiada A, Sambatakou H, A Toskas, G Vaiopoulos, et al. (2003) Mucormycosis: ten-year experience at a tertiary-care center in Greece. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis 22(12): 753-756.

- Nithyanandam S, Jacob MS, Battu RR, Thomas RK, Correa MA, et al. (2003) A retrospective analysis of clinical features and treatment outcomes. Indian J Ophthalmol 51: 231-236.

- Parfrey NA (1986) Improved diagnosis and prognosis of mucormycosis. A clinicopathologic study of 33 cases. Medicine (Baltimore) 65(2): 113-123.

- Bullock JD, Jampol LM, Fezza AJ (1974) Two cases of orbital phycomycosis with recovery. Am J Ophthalmol 78(5): 811-815.

- Maertens J, Demuynck H, Verbeken EK, P Zachée, G E Verhoef, et al. (1999) Mucormycosis in allogeneic bone marrow transplant recipients: report of five cases and review of the role of iron overload in the pathogenesis. Bone Marrow Transplant 24(3): 307-312

- Kontoyiannis DP, Wessel VC, Bodey GP, Rolston KV (2000) Zygomycosis in the 1990s in a tertiary-care cancer center. Clin Infect Dis 30(6): 851-856.

- Ingram CW, Sennesh J, Cooper JN, Perfect JR (1989) Disseminated zygomycosis: report of four cases and review. Rev Infect Dis 11: 741-754.

- Morrison VA, McGlave PB (1993) Mucormycosis in the BMT population. Bone Marrow Transplant 11(5): 383-388.

- Nosari A, Oreste P, Montillo M, G Carrafiello, M Draisci, et al. (2000) Mucormycosis in hematologic malignancies: an emerging fungal infection. Haematologica 85(10): 1068-1071.

- Baraia J, Munoz P, Bernaldo de Quiros JC, Bouza E (1995) Cutaneous mucormycosis in a heart transplant patient associated with a peripheral catheter. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis 14(9): 813-815.

- Marr KA, Carter RA, Crippa F, Wald A, Corey L (2002) Epidemiology and outcome of mould infections in hematopoietic stem cell transplant recipients. Clin Infect Dis 34(7): 909-917.

- Jimenez C, Lumbreras C, Aguado JM, Carmelo Loinaz, Gloria Paseiro, et al. (2002) Successful treatment of mucor infection after liver or pancreas–kidney transplantation. Transplantation 73(3): 476-480.

- Nampoory MR, Khan ZU, Johny KV (1996) Invasive fungal infections in renal transplant recipients. J Infect 33: 95-101.

- Morduchowicz G, Shmueli D, Shapira Z, S L Cohen, A Yussim, et al. (1986) Rhinocerebral mucormycosis in renal transplant recipients: report of three cases and review of the literature. Rev Infect Dis 8(3): 441-446.

- Sehgal A, Raghavendran M, Kumar D, Srivastava A, Dubey D, et al. (2004) Rhinocerebral mucormycosis causing basilar artery aneurysm with concomitant fungal colonic perforation in renal allograft recipient: a case report. Transplantation 78(6): 949-950.

- Quinio D, Karam A, Leroy JP, MC Moal, B Bourbigot, et al. (2004) Zygomycosis caused by Cunninghamella bertholletiae in a kidney transplant recipient. Med Mycol 42(2): 177-180.

- Mattner F, Weissbrodt H, Strueber M (2004) Two case reports: fatal Absidia corymbifera pulmonary tract infection in the first postoperative phase of a lung transplant patient receiving voriconazole prophylaxis, and transient bronchial Absidia corymbifera colonization in a lung transplant patient. Scand J Infect Dis 36(4): 312-314.

- Kerbaul F, Guidon C, Collart F, Hubert Lépidi, Bruno Cayatte, et al. (2004) Abdominal wall mucormycosis after heart transplantation. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth 18(6): 822-823.

- Tobon AM, Arango M, Fernandez D, Restrepo A (2003) Mucormycosis (zygomycosis) in a heart-kidney transplant recipient: recovery after posaconazole therapy. Clin Infect Dis 36(11): 1488-1491.

- Minz M, Sharma A, Kashyap R, Naval Udgiri, Munish Heer, et al. (2003) Isolated renal allograft arterial mucormycosis: an extremely rare complication. Nephrol Dial Transplant 18(5): 1034-1035.

- Ladurner R, Brandacher G, Steurer W, Stefan Schneeberger, Claudia Bösmüller, et al. (2003) Lessons to be learned from a complicated case of rhino-cerebral mucormycosis in a renal allograft recipient. Transpl Int 16(12): 885-889.

- Zhang R, Zhang JW, Szerlip HM (2002) Endocarditis and hemorrhagic stroke caused by Cunninghamella bertholletiae infection after kidney transplantation. Am J Kidney Dis 40(4): 842-846.

- Vera A, Hubscher SG, McMaster P, Buckels JA (2000) Invasive gastrointestinal zygomycosis in a liver transplant recipient: case report. Transplantation 73(1): 145-147.

- Warnock DW (1995) Fungal complications of transplantation: diagnosis, treatment and prevention. J Antimicrob Chemother 36: 73-90.

- Bertocchi M, Thevenet F, Bastien O (1995) Fungal infections in lung transplant recipients. Transplant Proc 27: 1695.

- Carbone KM, Pennington LR, Gimenez LF, Burrow CR, Watson AJ (1985) Mucormycosis in renal transplant patients-a report of two cases and review of the literature. Q J Med 57: 825-831.

- Haim S, Better OS, Lichtig C, Erlik D, Barzilai A (1970) Rhinocerebral mucormycosis following kidney transplantation. Isr J Med Sci 6(5): 646-649.

- Baddley JW, Stroud TP, Salzman D, Pappas PG (2001) Invasive mold infections in allogeneic bone marrow transplant recipients. Clin Infect Dis 32: 1319-1324.

- Waldorf AR, Ruderman N, Diamond RD (1984) Specific susceptibility to mucormycosis in murine diabetes and bronchoalveolar macrophage defense against Rhizopus. J Clin Invest 74(1): 150-160.

- Boelaert JR, de Locht M, Van Cutsem J, V Kerrels, B Cantinieaux, et al. (1993) Mucormycosis during deferoxamine therapy is a siderophoremediated infection. In vitro and in vivo animal studies. J Clin Inves 91(5): 1979-1986.

- MM, Zaoutis TE, Buchanan WL, Tena A Knudsen, Tatyana A Sarkisova, et al. (2005) Epidemiology and outcome of zygomycosis: a review of 929 reported cases. Clin Infect Dis 41(5): 634-653.

- Chakrabarti A, Das A, Sharma A, N Panda, S Das, et al. (2001) Ten years’ experience in zygomycosis at a tertiary care centre in India. J Infect 42(4): 261-266.

- Reid VJ, Solnik DL, Daskalakis T, Sheka KP (2004) Management of bronchovascular mucormycosis in a diabetic: a surgical success. Ann Thorac Surg 78(4): 1449-1451.

- Pavie J, Lafaurie M, Lacroix C, Anne Marie Zagdanski, Denis Debrosse, et al. (2004) Successful treatment of pulmonary mucormycosis in an allogenic bone-marrow transplant recipient with combined medical and surgical therapy. Scand J Infect Dis 36(10): 767–769.

- Asai K, Suzuki K, Takahashi T, Ito Y, Kazui T, et al. (2003) Pulmonary resection with chest wall removal and reconstruction for invasive pulmonary mucormycosis during antileukemia chemotherapy. Jpn J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 51(4): 163-166.

- Sun QN, Fothergill AW, McCarthy DI, Rinaldi MG, Graybill JR (2002) In vitro activities of posaconazole, itraconazole, voriconazole, amphotericin B, and fluconazole against 37 clinical isolates of zygomycetes. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 46(5): 1581-1582.

- Abzug MJ, Walsh TJ (2004) Interferon-gamma and colony-stimulating factors as adjuvant therapy for refractory fungal infections in children. Pediatr Infect Dis J 23(8): 769-773.

- Gil-Lamaignere C, Simitsopoulou M, Roilides E, Maloukou A, Winn RM, et al. (2005) Interferon-gamma and granulocyte–macrophage colony-stimulating factor augment the activity of polymorphonuclear leukocytes against medically important Zygomycetes. J Infect Dis 191(7): 1180-1187.

-

Amit Bhardwaj, Kratika Mishra, Shivani Bhardwaj, Anuj Bhardwaj. The Resurgence of Mucormycosis in the Covid-19 Era – A Review. 3(1): 2021. ACCS.MS.ID.000551.

-

Clinical; Detention; Electrotherapy

-

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.