Research Article

Research Article

Determine Significant Factors Related to Malaria among Pregnant Women in Nigeria by Logistic Regression Analysis

İlker Etikan*, Rukayya Alkassim, Özgür Tosun, Yavuz Sanisoğlu S and Meliz Yuvalı

Department of Biostatistics, Near East University, Cyprus

İlker Etikan, Department of Biostatistics, Near East University, Faculty of Medicine, Nicosia-TRNC, Cyprus.

Received Date: January 28, 2019 Published Date: February 15, 2019

Abstract

Objectives: Malaria during antenatal period was a major health problem that lead to both mother and child death. The aim of this study is to assess the predictors of malaria during pregnancy among six states of Nigeria based on anti-malarial pill prescribed to pregnant women by the health facility.

Methods: The analysis involves chi-square test for independent association between the predictors and risk of malaria diagnosis among the qualitative variables, Mann Whitney u test for quantitative variables and binary logistic regression for the multivariate analysis.

Results: The analysis shows that the risk of malaria during pregnancy was significantly associated with Age, IPTp-up take, ITN use, source of energy for lightening, main material use for room’s rooftop and livestock keeping. This shows that, appropriate use of insecticide treated bed nets, optimal IPTp uptake against malaria and other protective measures, teamed with some elements such as sources of energy for lightening and main material for room’s rooftop decreased the incidence of malaria infectious disease among antenatal women.

Conclusion: The research suggested that the illiterates and poor women are less probable of using these preventive measures in other to reduce the spread of malaria disease among pregnant women and entire population as whole.

Keywords:Malaria; Pregnancy; Chi square test; Mann whitney - U test; Logistic regression

Introduction

A life hostile parasitic infectious disease conveyed by female anopheles mosquitoes is called malaria [1]. In human body, malaria is caused by a protozoan of the Plasmodium type of the four subspecies, which include P.falciparum, P.vivax, P.malariae and P.ovale. The subspecie that causes greatest sickness and death in African countries was P. falciparum. This parasitic disease is transmitted by the bites of female anopheles mosquitoes of the genus Anopheles which is the most efficient and responsible for disease transmission in Africa [2]. Initially the parasite starts by infecting the liver where it begins to build up. After some days, the developing parasites are discharged into the blood stream to infect the red blood cells, where they continue to increase, ultimately bursting the red blood cells and infecting others in advance. If they reach high numbers, they may cause severe disease or even death as well [3].

One of the major health problems that cause both maternal and neonatal mortality is malaria during pregnancy. Low birth weight is one of the major factors that cause child mortality, where malaria during pregnancy reduces the birth weight. In Africa, maternal and neonatal mortality were associated with up to 300,000 death estimate in each year as indicated by statistics [4]. Luxemburger [5] make an estimate among Koran population living in Thailand, malaria during antenatal period have an effect on child mortality during the first month of child’s life [6]. Examined the Status of Pregnant Women having in Lagos State, Nigeria [7]. Examined the Inferiority of Single-Dose Sulfadoxine-Pyrimethamine Intermittent Preventive Remedy for Malaria during the pregnancy of women with HIV-Positive Zambia [8].

Determined the Prevalence of Malaria Parasite Infection among Pregnant Women in Osogbo, Southwest of Nigeria [9]. Examined the prevalence of malaria parasite infection among pregnant women living in a suburb of Lagos, Nigeria [10]. studied the Effects of Malaria and Intermittent Preventive (IPTp) Treatment during Pregnancy on Fetal Anemia in Malawi with Unconditional linear and logistic regressions [11]. studied the Impact of malaria during pregnancy on pregnancy outcomes in Ugandan potential cohort with intensive malaria screening and prompt treatment using Multivariate analysis [12]. Made an assessment of the spatial pattern of malaria infection in Nigeria. The pattern of spatial variation in the rate of malaria infection was analyzed using principal component analysis (PCA) [13].

Measured the level and predictors of optimal IPTp-SP doses in six districts of Tanzania using Chi-Square to test the independent association between IPTp uptake and risk factors of malaria during antenatal period, and multinomial logistic regression for multivariate analysis [14]. Studied the Epidemiology of Malaria Infection in Pregnant Women in Some selected areas of Nassarawa State, Nigeria [15]. investigated the prevalence and risk factors of malaria based on the rapid diagnosis test (RDT) in Ethiopia.

Methods

Data and area

The information use in this research was a documented data obtained from National Bureau of Statistics Nigeria, it was health results based on financing Nigeria in the year 2013, and the survey was conducted by Federal ministry of Health in collaboration with National Bureau of statistics and World Bank. It was an exit interview for antenatal care visit in six states of Nigeria namely Adamawa, Benue, Nassarawa, Ogun, Ondo and Taraba State which represent the six geopolitical zones of Nigeria. The data was analyzed both descriptively and inferentially using standard methods of applied statistics in health sciences.

Variables

The dependent or outcome of interest is prescription or given Quinine or Fansidar antimalarial pills by the health worker at ANC unit. Many drugs such as Arthimeter, chloroquine and pyrimethamine/sulfadoxine (Fansidar) are the most common drugs used for curing malaria in Nigeria and Africa as whole, such drugs assist in malaria treatment during pregnancy [16]. Thus, the dependent variable is binary, signifying whether or not a person was positive for malaria according to these antimalarial pills prescription, and it was derived from the question: “During this visit, has a health worker given or prescribed you any antimalarial pills?” The response was categorized in two categories such that:

Given or prescribed antimalarial pills = Independent variables include Age, Highest level of Education, marital status, spouse education level, pregnancy weeks, IPTp uptake, primigravidae status, use of insecticide treated net, health insurance scheme, land asset, total family, main source of water, main source of energy for cooking and lightening, main material use for house wall, roof and floor, number of nets/person and livestock keeping.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis play an important role in medical research area and the estimates and predicted values obtained provides change in the dynamic of epidemiology of malaria among antenatal women in a valuable vision. Therefore this study employs the application of logistic modeling to analyze factors associated with malaria during pregnancy, and the model obtained was purely based on statistical result. The analysis was done using univariate, bivariate and Multivariate statistical method. In the univariate analysis, frequency distribution and percentages for each qualitative variable while median and interquartile range (IQR) of the each quantitative variable were stated. Secondly, bivariate analysis was conducted, in which the outcome variable, presence or absent of malaria was cross tabulated against each and every independent variable. The statistical significant relationship between each pair of variables was tested using Pearson’s Chi-Square (χ2) test, for the categorical variables, while for the continuous variables, due to violation of normality assumption which is one of the main parametric assumptions, a non-parametric version of independent sample t- test was used, hence Mann Whitney U test was considered to test the difference between each predictor with the response variable. Where p-value less than 5% (p-value ≤ 0.05) of the outcome and each of the independent variables reject the hypothesis of no significant association between the variables, and hence concluded that they were significantly associated, else, no association was deduced.

An interaction between the significant variables in the multivariate analysis was also done to see the significant association for interaction between variables. The category “present of malaria” of the outcome variable was made a baseline/ reference outcome hence assessing what predicts absence of malaria. For multivariate analysis, selection of predictor variables for building model depends on each one’s to become statistically significant in the overall model. Also the model was assessed using Hosmer and Lemeshow’s test from the measures of model fit.

Results and Discussions

A total of 1,676 antenatal women aged from 9 to 48 responded to malaria related questions fromsix states of Nigeria, of which 39.7% were from Adamawa state, 6.1% from Benue state, 16.6% from Nassarawa state, 5.0% from Ogun state, 22.3% from Ondo state and 10.3% were from Taraba state, all missing values were excluded. The majority of women (97%) were married, and about 32.2% have secondary education level. Occupationally, majority of the pregnant women were livestock keepers. From the descriptive statistics result, it was observed that 49.5% of the women were prescribed or given an antimalarial pill by the health facility, while 50.5% of the pregnant women were not prescribed. Furthermore, 60.1% of the women were multigravidae, 44.3% take partial intermitted preventive treatment against malaria, while 20.3% took optimal IPTp-doses. Also 51.7% were using insecticide treated net, while only 9.6% of the women were covered under health insurance scheme.

Bivariate analysis

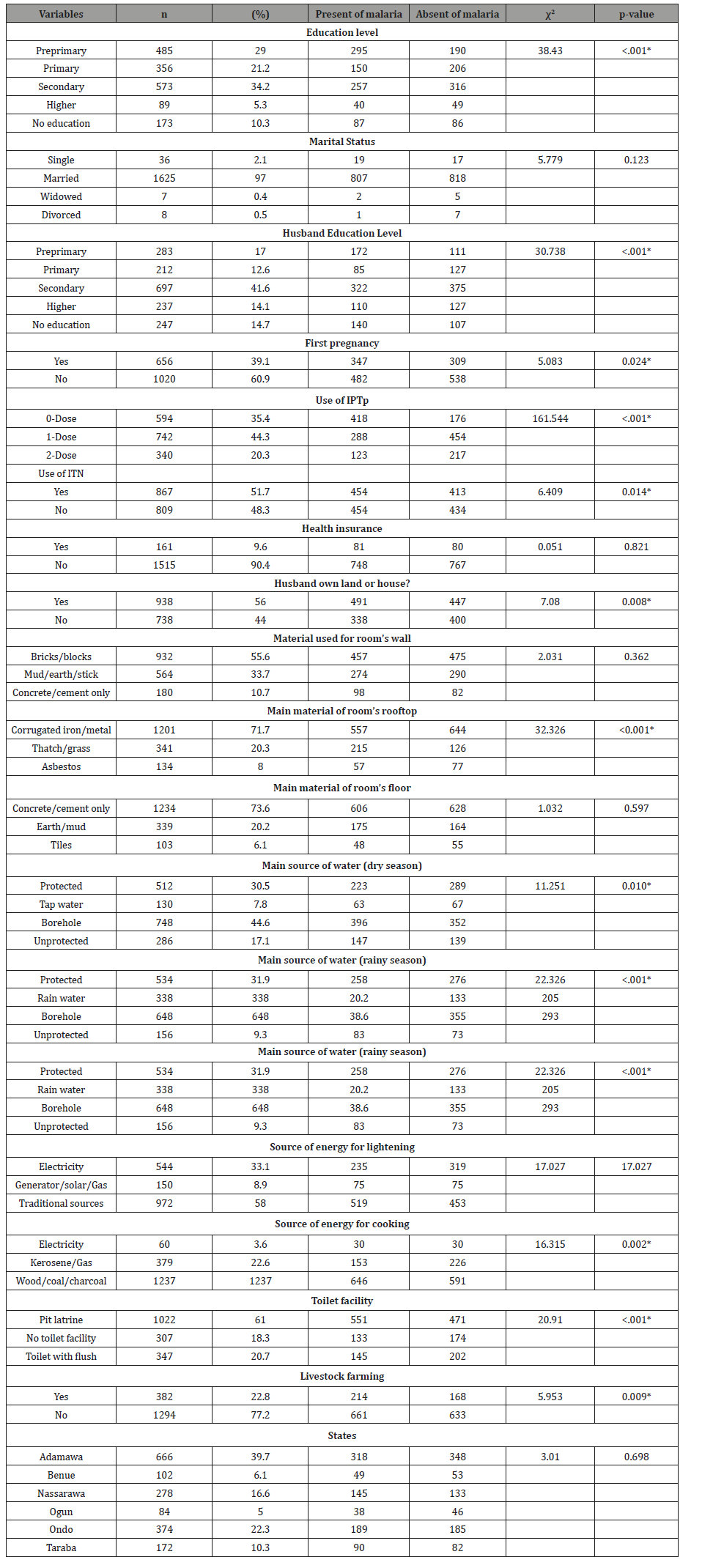

In the Bivariate analysis, chi-square test was employed for the categorical variables, educationlevel of the pregnant women was found to have a significant association with malaria diagnosis (p < 0.001), majority of preprimary educated women were malaria positive, while majority of women with secondary education level were malaria free. Marital status was insignificant, whereas husband education level have a significant relationship with malaria diagnosis (p < 0.001). From the chi square test result, it was observed that spouses with secondary education level, their wives were most likely malaria free. Primigravidae has a significant relationship with malaria diagnosis (p = 0.024). Such that malaria positive was highest among primigravidae compared to multigravidae. Furthermore, use of intermitted preventive treatment against malaria was found to have a significant association with malaria risk (p < 0.001), were majority of women with positive malaria did not received either partial or optimal IPTp- doses. While most of them with partial IPTp were malarial free. Use of ITN was found to have a statistical significant relationship with malarial diagnosis (p = 0.014). Health insurance scheme was found to have insignificant relationship with malaria risk, as well as material used for room’s wall and floor. But material used for room’s rooftop was found to have a significant relationship with malaria risk (p < 0.001), were majority of women with corrugated iron/metal were found to be malaria positive. Main sources of water for drinking during both dry and rainy season were found to be significant (p = 0.010 and p <0.001). Women drinking borehole water, were found have malaria risk diagnosis in both seasons (Table 1).

Table 1: Independent test for malaria status versus all the qualitative predictor variables.

Main source of energy for lightening was found to have a statistical significant relationship with malaria risk (p < 0.001), where majority of pregnant women using traditional source of lightening were found to be malaria positive. Also main source of energy for cooking was found to have a statistical significant relationship with malaria diagnosis (p = 0.002), in which majority of women using wood/coal/charcoal were found to be malaria positive. Toilet facility was a significant factor of malaria (p < 0.001), in which majority of women using pit latrine were found to be malaria positive. Occupationally, livestock keepers have a significant relationship with malaria diagnosis (p = 0.009), such that majority of livestock keepers women were found to be malaria positive, whereas relationship with malaria risk and states was in significant (Table 2).

Table 2: Independent test for malaria versus all qualitative predictors.

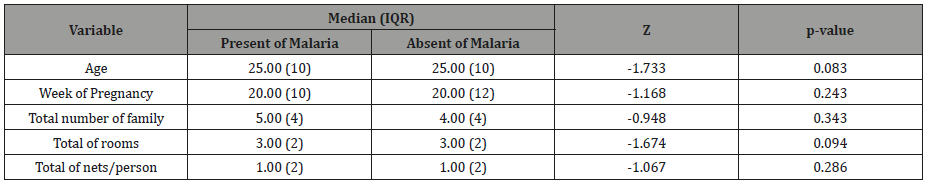

For continuous variables, Mann Whitney U-test was used to test the difference between the response and the predictors, due to violation of one of the main parametric assumption which is normality. Based on the result obtained, median age of positive and negative malaria was 25years with interquartile range (10), median weeks of pregnancy was 20weeks with interquartile range for positive and negative malaria (10 and 12) respectively, median total number of family was 4 and 5 with interquartile range (4), median number of rooms was 3 with IQR (2) and median number of nets per person is 1 with IQR (2). All the qualitative variables were found to be insignificant at 0.05 level of significant (Table 3).

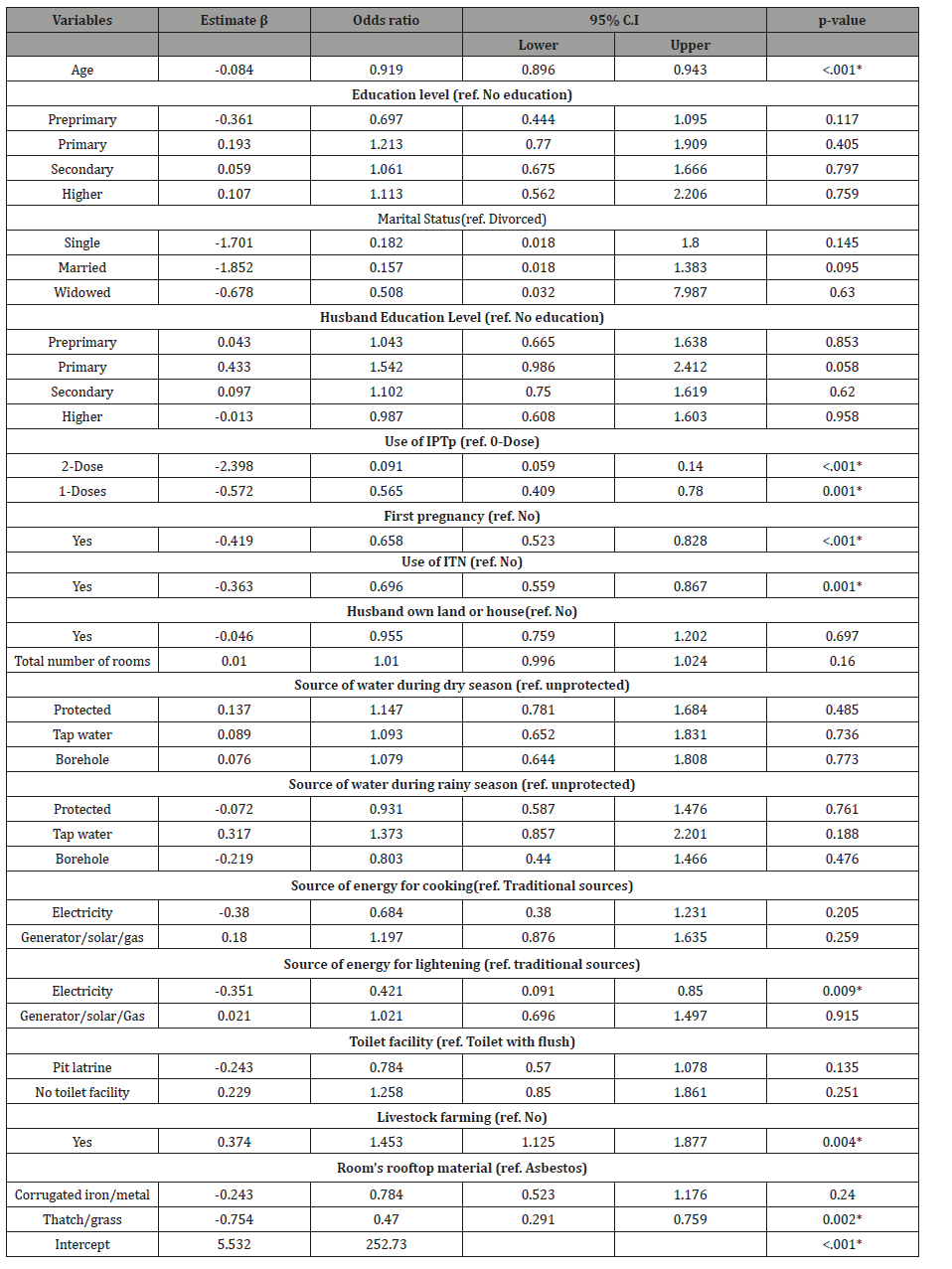

Table 3: Logistic regression with multiple variables.

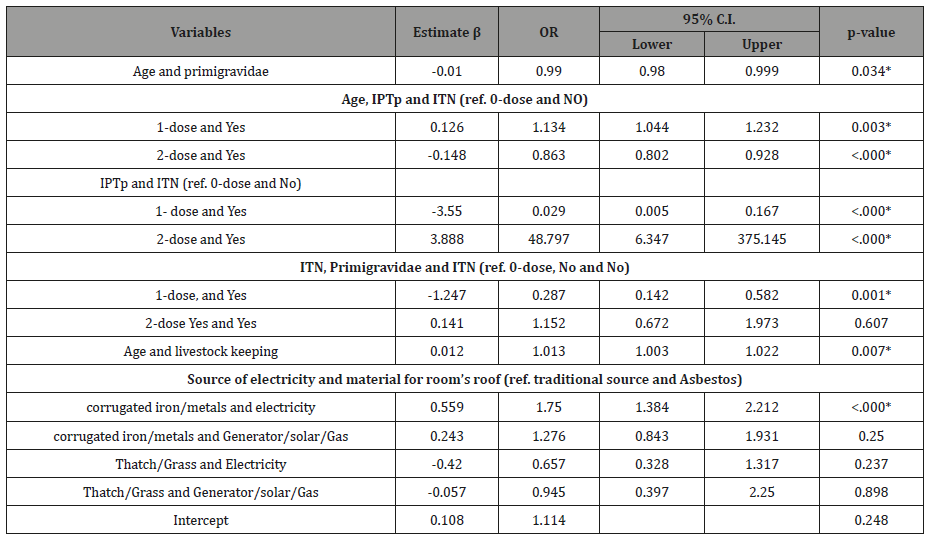

Table 4: Logistic regression for multiple variables with interaction.

Binary logistic regression analysis was done between the variables without interaction between them, to see their effect in the model. Table 3 gives the estimates of significant geographic, socio-economic and demographic factors on malaria during pregnancy. Based on the outcome obtained, malaria risk increases by 8.1% among pregnant women with unit increase in age (OR=0.919, 95% CI=0.896 – 0.943). furthermore women who took optimal IPTp doses, were 90.9% less likely diagnosed as malaria positive compared to those who did not received the treatment at all (OR=0.091, 95% CI=0.059 – 0.140) as well as those that received partial IPTp dose, the risk of positive malaria decreased by 43.5% (OR=0.565 95% CI=0.409 – 0.780) compared to those with none or 0-IPTp dose. First pregnancy was a statistical significant predictor of malaria diagnosis (p < 0.001), such that the odds of positive malaria among premigravidae was found to be 34.2% compared with multigravidae (OR=0.658, 95% CI=0.523 – 0.828). Furthermore, insecticide treated net was found to be a significant predictor of malaria during pregnancy (p = 0.001). Pregnant women using ITN were 30.4% less likely than those who were not using ITN (OR=0.696, 95% CI=0.559 – 0.876). Source of energy for cooking was found to be a significant predictor of malaria during pregnancy, such that women using electricity for cooking were 57.9% less probable to have positive malaria (OR=0.421, 95% CI=0.091 –0.850) compared with traditional sources users. Livestock keeping was also a significant predictor of malaria risk. The relative risk of Livestock keepers among pregnant women was significantly 1.453 higher compared to those who were not livestock keepers (OR=1.453, 95% CI=1.125 – 1.877). Main material for room’s rooftop was also a significant predictor of malaria risk. Women with thatch/grass were found to be less likely compared to those with asbestos (OR=0.470, 95% CI=0.291 – 0.759) (Table 4).

An interaction between age and first pregnancy was significant predictor of malaria diagnosis (p = 0.034), malaria risk decreases among women with first pregnancy with unit increase in age (OR=0.034, 95% CI=0.980 – 0.999). Furthermore, malaria risk increases with 1.135times among pregnant women using ITN and partial IPTp uptake with unit increase in age (OR = 1.134, 95% CI = 1.044 – 1.232). With reference to those who did not take IPTp dose and were not using ITN, malaria risk decreases with 13.7% among women with first pregnancy with unit increase in age (OR = 0.863, 95% CI = 0.802 – 0.928). Furthermore, with reference to 0-IPTp dose and ITN free, positive malaria risk was significantly less probable among antenatal women with partial IPTp-uptake and ITN use (OR = 48.797, 95% CI = 6.347 – 375.145).

The two models were assessed using Hosmer lemeshow’s test which suggested sufficient evidence that the data fits in the postulated Model set used in predicting malaria among Nigerian pregnant women. Hence, this indicates that the risk factors are not significantly different from those foretold by the model and the overall model fit is clear.

Conclusion

This study assessed some factors associated with malaria among pregnant women in Adamawa, Benue, Nassarawa, Ogun, Ondo and Taraba States of Nigeria. Overall 20.3% took optimal IPTp-doses, which was much lower than 43.6% in Tanzania [12] and 31.6% in Malawi [9]. Also 44.3% take partial IPTp-doses, and this was much higher than 28.5 in Tanzania. About 32.2% have secondary education level. This inprove the result obtained from Ibadan by [15] the poor IPTp uptake was affected by lack of awareness of the course of action, illiteracy and the ANC site problem. The findings of the association between some risk factors are equivalent to some results obtained from previous studies [12-14]. In addition to this in 2007 and 2012, study was conducted by Adefioye et al and Rogawski et al. [1, 9] in Nigeria and Malawi, respectively. The study reveals that appropriate use of insecticide treated bed nets, IPTp and other measures such as sources of energy for lightening and main material for room’s rooftop will decreased in incidence of malaria among antenatal women. However, the research suggested that the illiterates and poor women are less probable of using these protective measures in other to reduce the spread of malaria disease among pregnant women and entire population as whole.

Acknowledgement

We would like to thank the Federal Ministry of Health Nigeria who volunteered for our surveys in this research.

Conflict of Interest

No conflict of interest.

References

- WHO (1999) New Perspectives: Malaria Diagnosis Report of a Joint WHO/USAID: Informal Consultation held on 25-27 October 1999? World Health Organization, Geneva, Switzerland 2000: 4-48.

- Nchinda TC (1998) Malaria: a reemerging disease in Africa. Emerging infectious diseases 4(3): 398-403.

- Miller LH, Good MF, Milon G (1994) Malaria pathogenesis. Science 264 (5167): 1878-1883.

- Yoriyo, Kennedy P, Hafsat B (2014) Prevalence of Malaria Infection among Pregnant Women Attending Antenatal Clinics in Gombe State. International journal of entrepreneurial development, education and science research 2(1): 214-220.

- Luxemburger C, McGready R, Kham A, Morison L, Cho T, et al. (2001) Effects of malaria during pregnancy on infant mortality in an area of low malaria transmission. Am J Epidemiol 154(5): 459-465.

- Okwa OO (2003) The status of malaria among pregnant women: a study in lagos, Nigeria. Afr J Reprod Health 77-83.

- Gill CJ, Macleod WB, Mwanakasale V, Chalwe V, Mwananyanda L, et al. (2007) Inferiority of single-dose sulfadoxine-pyrimethamine intermittent preventive therapy for malaria during pregnancy among HIV-positive Zambian women. Journal of Infectious Diseases 196(11): 1577-1584.

- Adefioye OA, Adeyeba OA, Hassan WO, Oyeniran OA (2007) Prevalence of malaria parasite infection among pregnant women in Osogbo, Southwest Nigeria. American-Eurasian Journal of Scientific Research 2(1): 43-45.

- Raimi OG, Kanu CP (2010) The prevalence of malaria infection in pregnant women living in a suburb of Lagos Nigeria. African Journal of Biochemistry Research 4(10): 243-245.

- Rogawski ET, Chaluluka E, Molyneux ME, Feng G, Rogerson SJ, et al. (2012) The effects of malaria and intermittent preventive treatment during pregnancy on fetal anemia in Malawi. Clin Infect Dis 55(8): 1096- 102.

- De Beaudrap P, Turyakira E, White LJ, Nabasumba C, Tumwebaze B, et al. (2013) Impact of malaria during pregnancy on pregnancy outcomes in a Ugandan prospective cohort with intensive malaria screening and prompt treatment. Malar j 12(1): 139.

- Andrew O (2014) An assesment of the spatial pattern of malaria infection in Nigeria. International Journal of Medicine and Medical Sciences 6(2): 80-86.

- Exavery A, Mbaruku G, Mbuyita S, Makemba A, Kinyonge IP, et al. (2014) Factors affecting uptake of optimal doses of sulphadoxinepyrimethamine for intermittent preventive treatment of malaria in pregnancy in six districts of Tanzania. Malaria journal 13(1): 22.

- Alaku IA, Abdullahi AG, Kana HA (2015) Epidemiology of Malaria Parasites Infection among pregnant women in some part of Nasarawa State, Nigeria. Epidemiology 5(2): 30-33.

- Ayele DG, Zewotir TT, Mwambi HG (2012) Prevalence and risk factors of malaria in Ethiopia. Malar J 11(1): 195.

- Unicef (2000) Malaria prevention and treatment, UNICEF’s Programme Division in cooperation with the World Health Organization: 1-16.

-

İlker Etikan, Rukayya Alkassim, Özgür Tosun, Yavuz Sanisoğlu S, Meliz Yuvalı. Determine Significant Factors Related to Malaria among Pregnant Women in Nigeria by Logistic Regression Analysis. Annal Biostat & Biomed Appli. 1(4): 2019. ABBA.MS.ID.000517.

Pregnant Women, Malaria, Logistic Regression Analysis, Biostatistics, Population, Parasitic infectious disease, Plasmodium type, Anopheles mosquitoes, Geopolitical zones,

-

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.