Research Article

Research Article

Yoga and Its Effect on Glycemic Control and Oxidative Stress in People with Type 2 Diabetes in A Randomized Trial: Systematic Review and Meta- Analysis

Rashmi Shiju1*, Monira Al Arouj1, Jaakko Tuomilehto2,3,4 and Abdullah Bennakhi1

1Dasman Diabetes Institute, Kuwait

2Finnish Institute for Health and Welfare, Helsinki, Finland

3Department of Public Health, University of Helsinki, Helsinki, Finland

4Diabetes Research Group, King Abdulaziz University, Jeddah, Saudi Arabia

Rashmi Shiju, M Pharm, Msc, office of regulatory affairs, Dasman Diabetes Institute, Kuwait.

Received Date: February 09, 2020; Published Date: February 19, 2020

Abstract

Background:b> Yoga is being evaluated for its potential beneficial effect on people with type 2 diabetes(T2DM) as an adjuvant therapy by researchers around the globe. Few systematic reviews and meta-analyses previously performed have indicated mixed effect of yoga. In this review we aimed to evaluate further whether yoga has an impact on metabolic parameters in people with T2DM.

Methods: Systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials (RCTs) comparing the practice of any type of yoga, asanas or pranayamas vs. standard care in adults with T2DM. The primary outcome was change in fasting plasma glucose and glycated haemoglobin (HbA1c). The secondary outcome was serum lipid profile and oxidative stress. The electronic databases such as, Cochrane CENTRAL, Scopus, Medline, Embase and CINAHL were searched from the year 1990 to August 2015 to find out the studies done on yoga as per the eligibility criteria. Meta-analysis was conducted using the inverse variance method of analysis with random-effect models with checks of heterogeneity using the I2 test.

Results:b> From a total of 788 articles screened, nine RCTs were included involving 788 participants. In five trials yoga group had a significant reduction in HbA1c ( mean difference(MD) -0.51% , 95%CI -0.57 to -0.44, P =0.006, fasting plasma glucose (mean difference(MD) as -25.2 ,95 % CI -25.31 to -25.2mg/dl, P <0.00001, and serum LDL (mean difference(MD) -26.8mg/dl , 95% CI -42.1 to -11.5 mg/dl, p =0.0006), HDL (mean difference(MD) 6.8 mg/dl (95% CI 4.8 to 8.7, p <0.00001), total cholesterol (mean difference(MD) -33.3 mg/dl (95% CI -35.8 to -30.8, p <0.00001), triglycerides (mean difference(MD) 39.4 mg/dl( 95% CI -50.0 to -28.8, p <0.00001), cortisol (mean difference(MD) -5.5 μg /l ( 95% CI -7.1 to -4.0, p <0.00001), malondialdehyde (mean difference(MD) 16.6 nanomol/dl (95%CI -22.0 to -11.2, p<0.00001).

Conclusion:The results from the available trials indicate that yoga may be a potentially beneficial intervention for improving glycemic control, lipid profile and indicators of oxidative stress in people with T2DM. Further studies are required to corroborate yoga’s effect on other outcomes such as psychosocial profiles.

Keywords: Yoga; Systematic review; Meta-analysis; T2DM; Stress

Abbreviations: BMI: Body Mass Index; CAM: Complementary and Alternative Medicine; FBG: Fasting Blood Glucose; HDL: High Density Lipoprotein; LDL: Low Density Lipoprotein; MENA: Middle East and North Africa; MDA: Malondialdehyde; RCT: Randomized Controlled Trials; T2DM: Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus

Introduction

Diabetes mellitus is a progressive disease affecting large numbers of the people globally. According to the International Diabetes Federation (IDF) Atlas 9th edition, globally 463 million adults are affected with diabetes, and is estimated to rise to 700 million by 2045 without intervention [1]. Managing diabetes can be challenging and requires a multifaceted approach involving lifestyle changes and pharmacological intervention. People with diabetes do not infrequently use complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) with estimates ranging from 17% and 73% and involved lifestyle modification, yoga, qi gong, massage and herbs [2]. Yoga is the most common alternative holistic approach adopted by adults in many countries. According to national survey in the US, yoga use increased from 9.5% to 14.3% between 2012 and 2017 [3]. Yoga originated from India has been a traditional contemplative practice since time immemorial for the therapeutic intervention and health maintenance [4]. Yoga may be beneficial in almost all the ailments. [5-11]. It may have positive impact on endocrine system, nervous system, circulatory system, metabolism, psychology and cognition [12]. Yoga has also been shown to influence hormone regulation and studies suggest that regular practice of yoga can reduce cortisol and sympathetic activation while increasing serotonin, gaba aminobutyric acid (GABA) and oxytocin levels. [5,7,13,14]. This may in turn reduce anxiety, depression, perceived stress and improving sleep quality and male sexual functioning [15]. Yoga may have beneficial effect in people with T2DM, in terms of modifiable risk factors and metabolic syndrome [16-24]. The systematic review by Innes et al. [25] measured the influence of yoga-based programs on risk profiles in adults with type 2 diabetes. The review indicated that yoga may help in reducing the risk in adults with T2DM. The author also indicated that there are limited reviews to show the promising effect of yoga on psychological profiles in adults with diabetes. The systematic analysis by AlJasir et al. [26] showed that short-term benefit can be achieved by T2DM patient with the practice of yoga were however inconclusive and non-significant for the long-term outcomes of yoga practice. A systematic review and meta-analysis by Harpreet et al. [27] indicated that yoga participants successfully improved their glycated haemoglobin (HbA1c) as compared with the control people. Yoga also had significant improvements in lipid profiles, blood pressure, body mass index (BMI), waist/hip ratio and cortisol levels. A systematic review by Divya et al. [28] on effects of yoga on physical health and health related quality of life concluded that there were significant improvements in physical health and quality of life. In another systematic review and meta-analysis by Ramamoorthi et al. [29] reported significant improvements of yoga on glycaemic control, serum lipid profiles and other parameters in prediabetic populations. The present systematic review and meta-analysis will focus on patients with T2DM conducted through randomized controlled trials (RCTs) with yoga intervention such as Sudarshan kriya yoga, asanas, pranayamas and hatha yoga with duration at least four weeks. This review will give more focus to specific type of yoga intervention and its effect on glycaemic control, serum lipids and stress biomarkers. To our knowledge, this will be the first meta-analysis on oxidative stress markers.

Methods

Study selection criteria and PICOS

Cochrane review guidance was followed in conducting the systematic review [30].

Population for this systematic review was defined as:b> Adult patients aged 18 years or greater having T2DM for more than one year confirmed by a physician based on the guidelines for diagnosis of T2DM. Exclusion criteria included ;studies on infants and children, gestational diabetes, pregnant women, non-diabetic patients, type 1 diabetic patients, complication of diabetes and studies with herbal drug intervention.

The intervention included:b> any type of yoga (hatha, bikram, iyengar, sudarshan kriya yoga, pranayama, astanga, asanas), and minimum four week of duration of yoga. Comparison was control groups receiving standard treatment of care.

Outcomes:b> The primary outcomes were changes in fasting plasma glucose (FPG) and HbA1c. Secondary outcomes included changes in serum high density lipoprotein (HDl), low density lipoprotein (LDL) and total cholesterol, BMI, stress biomarkers and quality of life.

Study design: Only randomized clinical trial was selected for inclusion.

Database search strategy

The search strategy was implemented in ; Pubmed, Embase, Scopus, Cochrane, Medline, CINAHL Plus were searched using the key words “Yoga OR asana* OR Bikram OR Iyengar OR pranayama OR hatha OR ashtanga OR Sudarshan Kriya Yoga AND diabetes OR diabet* OR non-insulin dependent OR diabetes mellitus OR T2 DM OR Type II diabetes mellitus”. Apart from the database, the bibliography of the articles selected were also searched. Limits applied were for age greater than 18, articles published from 1990 to 2015, English language. Moreover, an internet searching was done through Google Scholar and also clinical trial.gov website for randomized controlled trials. Literature on systematic reviews and metaanalysis of yoga and diabetes published until 2019 were included.

The results obtained from searching each electronic database using the above-mentioned key words were saved in the computer and online End Note in order to keep a track of all searches which included number of hits, database name, time period searched, limitations applied. The results of search from each database also exported to Excel to sort out duplication and based on the eligibility criteria of systematic review.

Data extraction and screening

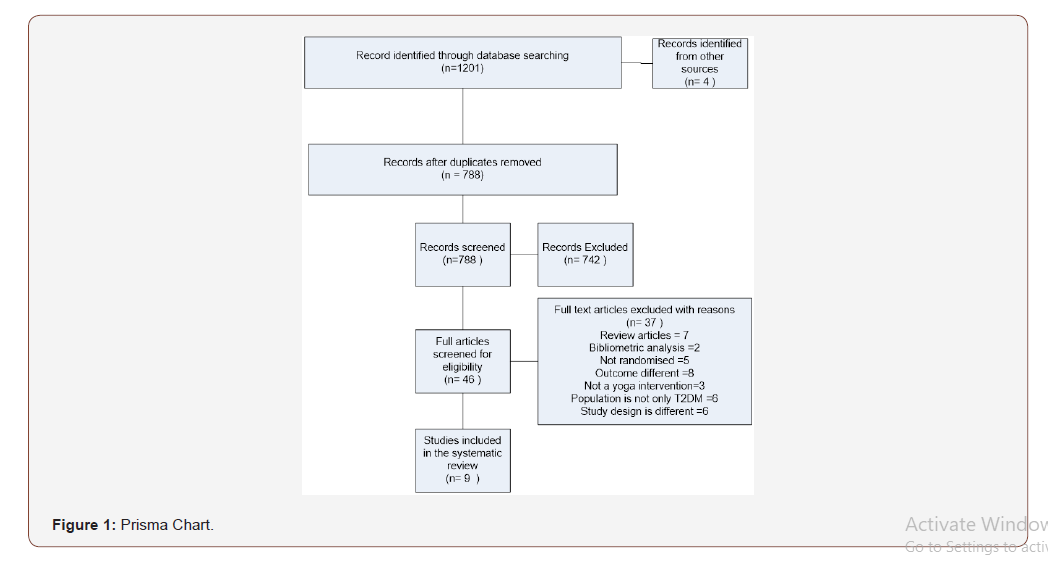

All the six databases were searched with key words mentioned and then screened for duplicates. The title and the abstract were screened for relevance. Full text articles were then scanned according to the eligibility criteria. The details of the number of articles excluded with reason are depicted in the flow chart (Figure 1). The results obtained from the database were extracted using the extraction form (Appendix I).

Quality assessment

A short scale of seven criteria customized to yoga studies were used to assess the quality of the included studies established by the Cochrane collaboration [30].

Following questions were included in the quality checklist:

• Whether participants were randomized to groups randomly or through software or independantly.

• Were the baseline characteristics of the study groups properly assessed or there was any correction done to balance.

• Whether the study has calculated sample size through power analysis.

• Whether the study has considered loss of follow up, attrition.

• Whether the study had properly handled the missing data by using intention-to-treat analysis,

• Study integrity; was the study followed as planned.

• Whether the study was conducted with certified progessional yoga instructor or not. Each criterion was rated as 0(study does not meet criteria) or 1 (study met criteria).

When a criterion meets six or seven points then the study is assessed as high quality and when four or five criteria were mint then assessed as low and very low when zero or one criteria were met. Data collected were assessed for the quality of studies based on the quality criteria. If a trial meets first three criteria, then it is categorized as low risk of bias. (Table 1).

Table 1:Characteristics of the final included studies.

Data Analysis

Meta-analysis of the eligible studies was conducted using statistical RevMan software measuring the mean differences using the generic inverse variance method of analysis. Meta-analysis was performed for HbA1c reported as a percentage and FPG reported as mg/dl. When the units for reported values of FPG in the articles differed, the units were Mmol/L they were converted into mg/ dl by multiplying the mmol/L value by 18. The generic inversevariance method of analysis was used to pool all mean differences for continuous data and for combining intervention effect estimates reporting results from fixed-effect and random-effects models. Statistical heterogeneity was assessed using the I-squared statistic. Mean difference was calculated for the yoga group and the control group. Standard deviation was also extracted from the reviewed articles. Standard errors were converted to standard deviation were appropriate.

Results

Characteristics of the studies

1201 titles and abstract were identified and, nine trials met the eligibility criteria that included 788 participants. Characteristics of included trials depicted in Table 2. Four trials (44.4%) reported HbA1C as primary outcome. Seven trials reported FPG an outcome but only one trial (11.1%) reported serum cholesterol, LDL, HDL triglycerides as an outcome. Two trials (22.2%) reported quality of life as an outcome. Most trials (55.6%) practiced three months of yoga as an intervention whilst this ranged from eight weeks to nine months in the remaining trials. The duration of each yoga class also varied between the trials from one and two hours.

Table 2:Risk bias of Included Studies.

Eight trials (88.9%) compared yoga to standard care while one trial used an educational intervention as a control group. The yoga type consisted asanas, pranayamas and meditation. One trial each used Sudarshan Kriya yoga, hatha yoga and vinayasa style yoga. The mean age of the participants was 55.0 years in yoga group and 53 years in the control group, 45.7 % of the participants were women in the yoga group and 51.5 % in the control group. All the nine trials were conducted under a certified yoga teacher.

Meta-analysis of the selected studies

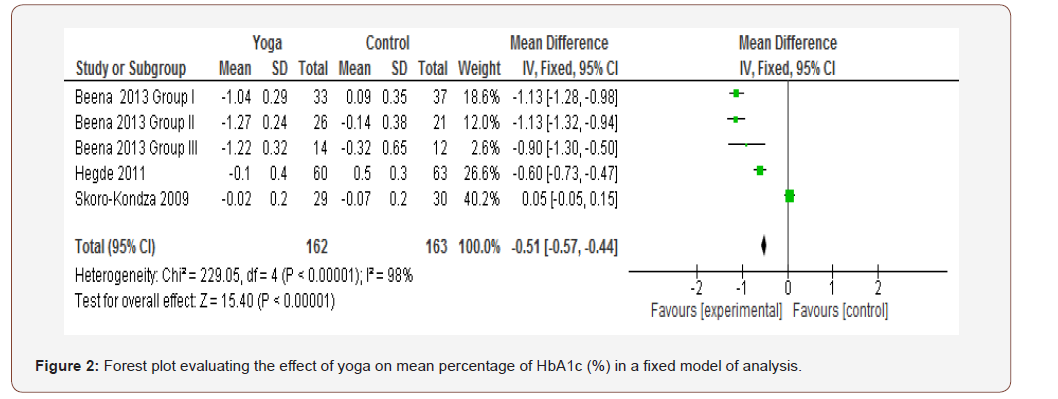

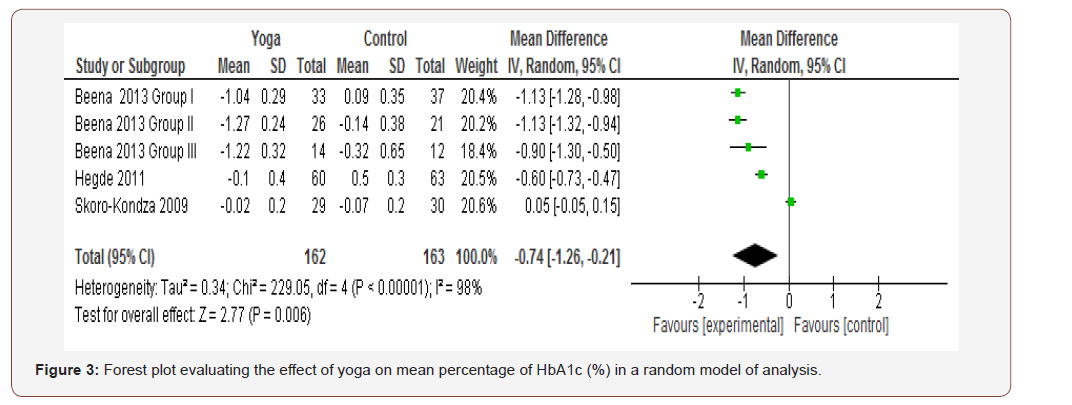

HbA1C: Out of the nine trials included for review, data from five trials could be included in the meta-analysis for HbA1c as the outcome with a continuous measure. Wen analysed using fixed model the mean change HbA1c with yoga compared with the control group was -0.51% (95% CI -0.57 to-0.44; p<0.00001) (Figure 2). Using random model, the mean difference in HbA1c was -0.74% (95 % CI -1.26 to -0.21; P = 0.006) with 162 participants in the yoga group vs 163 in the control group; heterogeneity chi2 =229.05, df =4 (P<0.00001), I2 = 98 %. (Figure 3).

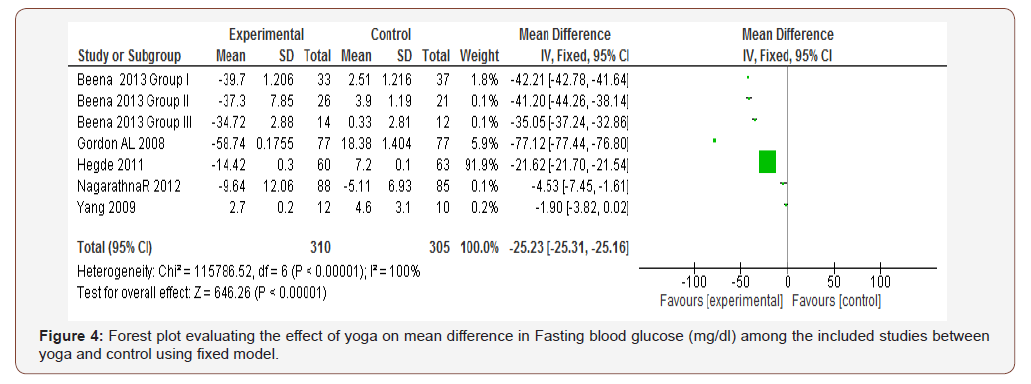

Fasting Plasma glucose: Out of the nine trials included in the review, data from three trials were included in the meta-analysis for FPG as the outcome with a continuous measure. Using fixed model, the mean difference in FPG with yoga was -25.2 (95% CI -25.3to -25.2, p<0.00001) mg/dl (Figure 4).

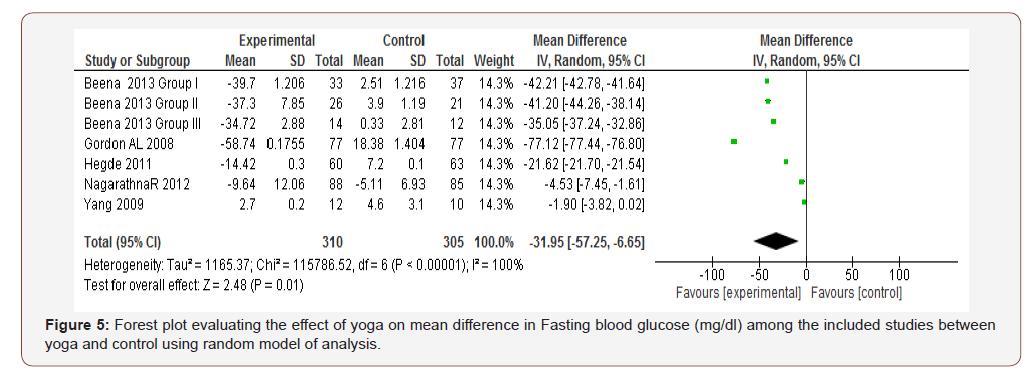

Using random model, the mean difference in FPG was -32.0 mg/ dl (95% CI -57.3 to -6.7, p =0.01) with 310 participants in the yoga group vs 305 in the control group. (Figure 5).

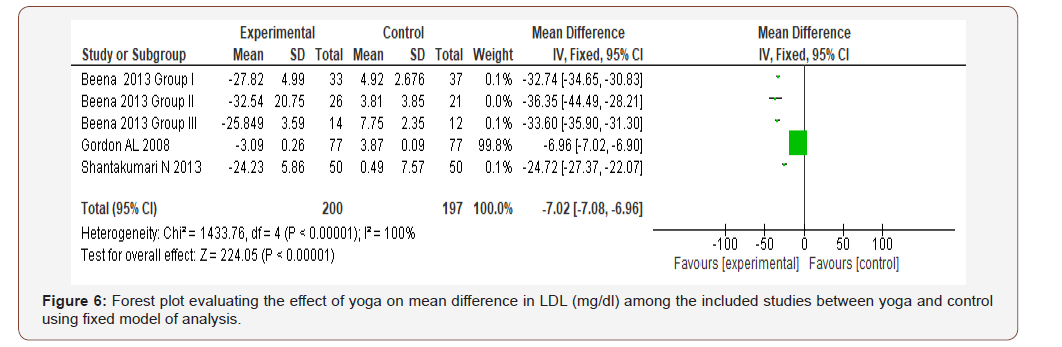

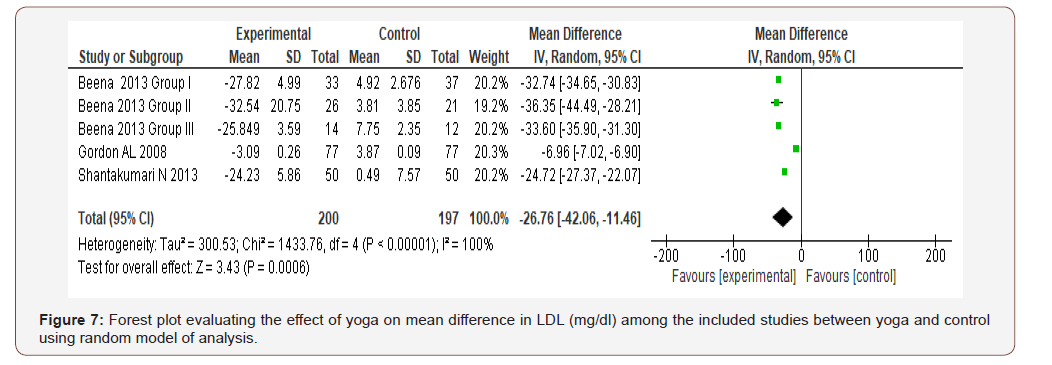

Serum low density lipoprotein (LDL): Out of the nine trials included for review, data from the three trials were included in the meta-analysis for LDL as the outcome with a continuous measure. Using fixed model, the mean difference in LDL in the yoga group as compared with the control group was -7.0(95% CI -7.1 to -7.0, p<0.00001) mg/dl (Figure 6). Using random model, the mean difference in LDL was -26.8 mg/dl (95% CI -42.1 to -11.5, p =0.0006) in the yoga group compared with the control group (Figure 7).

Serum high density lipoprotein (HDL)

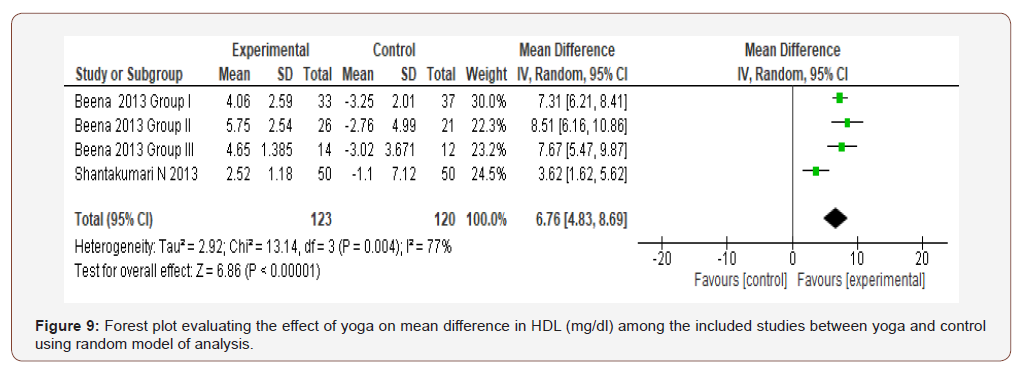

Two trials were included for the meta-analysis of HDL: Using fixed model the mean difference in HDL was 6.9 mg/dl (95% CI 6.1 to 7.7, p <0.00001) in the yoga group compared with the control group (Figure 8). Using random model, the mean difference in HDL was 6.8 mg/dl (95% CI 4.8 to 8.7, p <0.00001) in the yoga group compared with the control group (Figure 9).

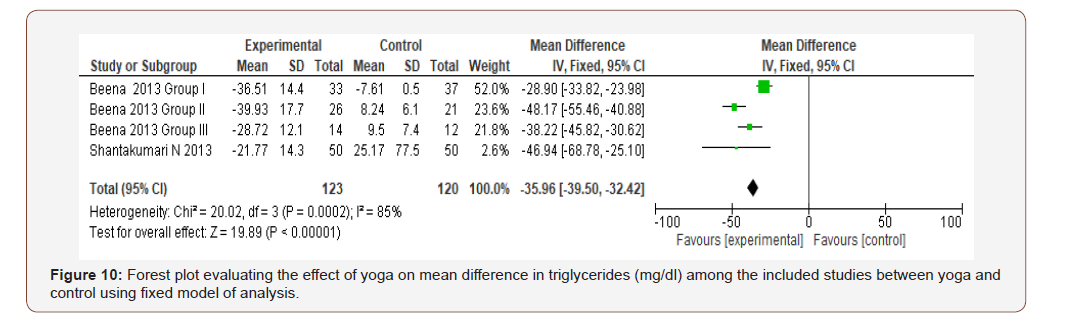

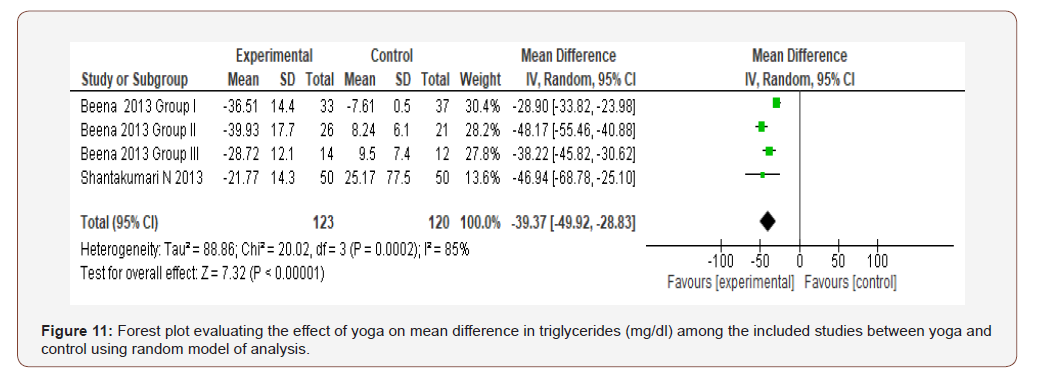

Serum triglycerides: Meta-analysis was conducted by measuring triglycerides from two trials and subgroup analysis. Using fixed model, the mean difference in triglycerides was –36.0 mg/dl (95% CI -40.0 to -32.4, p <0.00001) in the yoga group compared with the control group (Figure 10). Using random model, the mean difference in triglycerides was -39.4 mg/dl (95% CI -50.0 to -28.8, p <0.00001) in the yoga group compared with the control group (Figure 11).

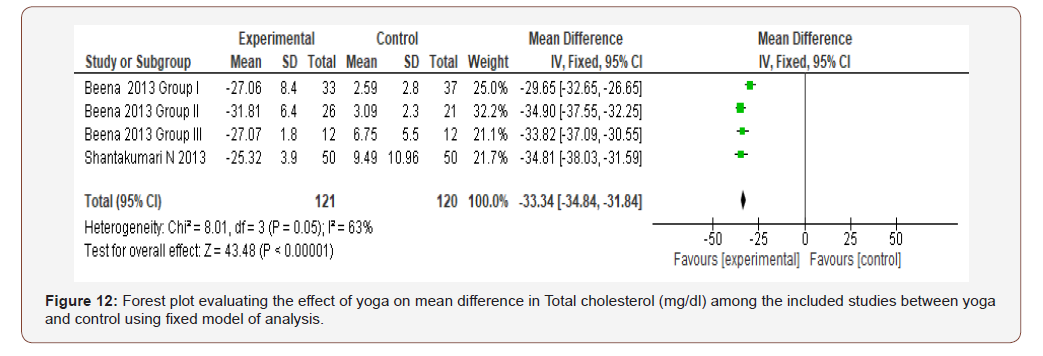

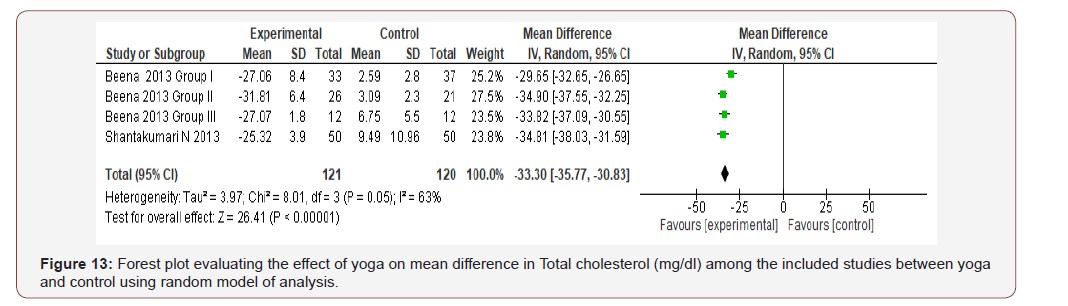

Serum total cholesterol: Two trials were included for the meta-analysis of total cholesterol. Using fixed model, the mean difference in total cholesterol was -33.3 mg/dl (95% CI -35.0 to -32.0, p <0.00001) in the yoga group compared with the control group (Figure 12). Using random model, the mean difference in total cholesterol was -33.3 mg/dl (95% CI -35.8 to -30.8, p <0.00001) in the yoga group compared with the control group (Figure 13).

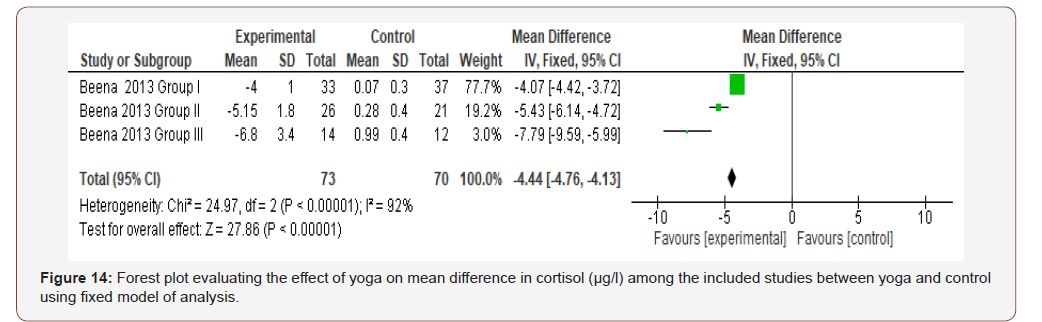

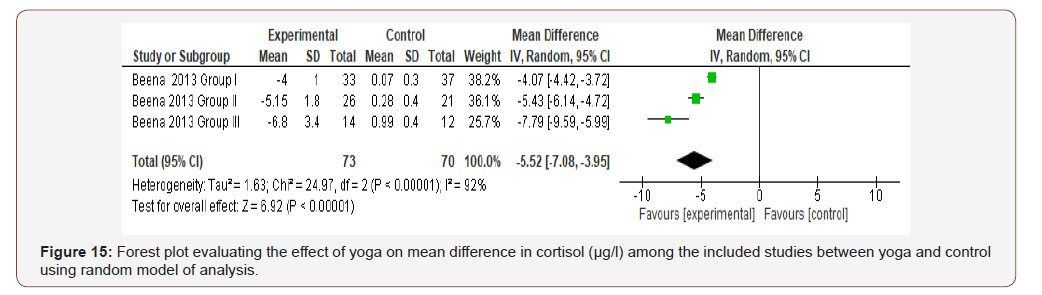

Cortisol: Two trials were included for the meta-analysis of cortisol measurement. Using fixed model, the mean difference in cortisol was -4.4 μg/L (95% CI -4.8 to -4.1, p <0.00001) in the yoga group compared with the control group (Figure 14). Using random model, the mean difference in cortisol was -5.5 μg/L (95% CI -7.1 to -4.0, p <0.00001) in the yoga group compared with the control group (Figure 15).

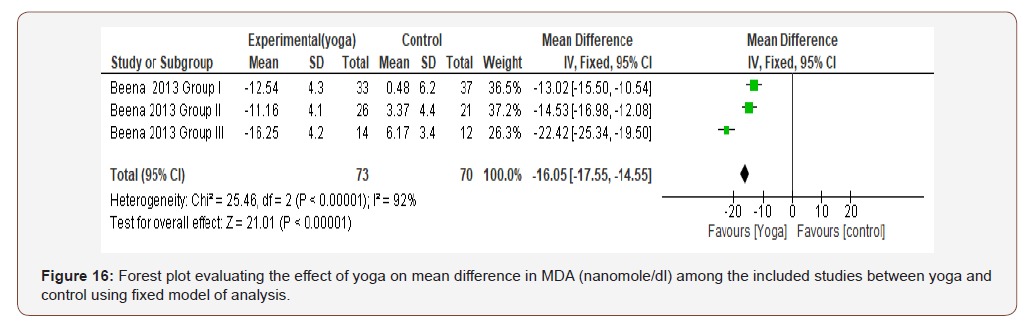

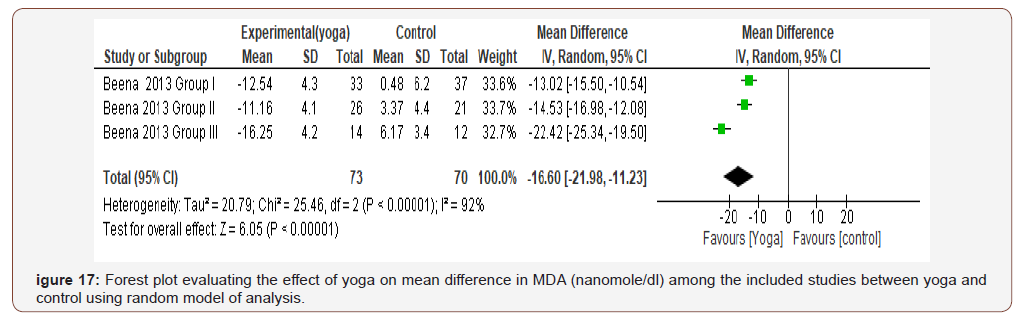

Malonaldehyde: One trial including three subgroups was included for the meta-analysis of malondialdehyde measurement. Using random model, the mean difference for malondialdehyde was 16.1 nanomol/dl (95%CI -17.6 to -14.6, p<0.00001) in the yoga participants compared with the control group. (Figure 16). Using random model, the mean difference for malondialdehyde was 16.6 nanomol/dl (95%CI -22.0 to -11.2, p<0.00001) in the yoga participants compared with the control group. (Figure 17).

Discussion

Effect of yoga on glycemic control

We identified nine trials and after undertaking meta-analysis we found that yoga was associated with a significant mean change in HbA1c and FPG, -0.74% and -32.0 mg/dl, respectively, using the random effect model in yoga participants compared with the controls. Five controlled trials Viveka [18], Mc Dermott [19], Yang [23], Gordan et al. [31], Nagarathna et al. [20] conducted to assess the effect of yoga on glycemic control reported a statistically significant effect of yoga on FPG. One of the trials reported FBG as an outcome but we did not include it in the meta-analysis due to the lack of the post- intervention measurement. Few of the trials reported the results of FBG in mmol/L and was converted to mg/ dl to have a uniform unit of measurement. The mean percentage difference in FBG between yoga group ranged from 3.0 to -22.1 %. The wide range may be attributed to trial populations which varied from population in Indi to the US, Cuba and London, UK. Moreover, the age of the research participants varied from 45 to 65 years; one of the trials was conducted on geriatric T2DM patients, age between 60-70 years [24]. Other RCTs [18,19,23] also reported a favourable effect of yoga on FBG but was not statistically significant, probably due to a small sample size.

In this review and meta-analysis on effect of yoga in the RCTs, a positive effect of yoga on FBG was found. The mean difference between yoga and control group for FBG was -25.2mg/dl (95% CI -25 to, -26) with fixed model. Due to heterogeneity of the results, random model was selected and the mean difference between yoga and control group for FBG was -32mg/dl (95% CI -57 to, -7). This is in concordance with the systematic review and meta-analysis by [32-34]. They reported a significant -26 mg/dl,95% CI,-41,-11), decrease in FBG in the yoga group as compared with the control group with a pooled weighted mean difference of -24 mg/dL (95% CI , 38 to 10), standardized mean difference (SMD), -1.4, (95%CI -2 to 1). Another, meta-analysis by Vizciano et al. [35] indicated a nonsignificant effect of yoga on FBG. Al Jasir [26] reviewed four studies for the effect of yoga on FBG and reported the mean difference between yoga and control group which ranging from -29 to -41 mg/ dl. Of the four trials, three trials showed a statistically significant effect of yoga on FBG. The variation in the result may be due to methodological factors, different way of measuring the outcome, selected population, age, concealment, blinding and intervention period of yoga.

Of the nine eligible trials which assessed the effect of yoga on the glycemic control in the present analysis, only two individual trials [17,24] reported statistically significant effect of yoga on HbA1c. While RCTs [18-20,23,31] reported an improvement in HbA1c which was statistically non-significant. This may be due to a small sample size, variability in methods, compliance to yoga, and duration of yoga practice. In this systematic review and metaanalysis of five trials, the mean difference in HbA1c between the yoga and control groups was found to be -0.7%, (95 % CI -1.26 to-0.21.) and overall effect size of 2.77 ( P= 0.006) This is in concordance with a systematic review by Cui et al. [32] that included twelve studies and reported for HbA1C the mean difference between yoga and control was -0.47% (95 % CI 0.87 to -0.07).

Effect of yoga on lipid profiles

The meta-analysis of RCTs shows a significant effect of yoga on LDL, HDL, total cholesterol and triglycerides. Mean difference between the yoga and control groups in LDL was -26.8 mg/dl (95% CI -42.1 to,-11.5), change in total cholesterol was -33.3 mg/dl (95% CI -35.8 to -30.8, p <0.00001) , triglycerides was -39.4 mg/dl( 95% CI -50.0 to -28.8, p <0.00001) in the yoga group , HDL was 6.8 mg/ dl( 95% CI 4.8 to 8.7, p <0.00001in a random mode of analysis. Out of nine tirals, six studies measured serum lipid profiles. Only three studies reported a significant effect of yoga on lipids. [20,21,24].

Effect of yoga on oxidative stress

In this meta-analysis of subgroups of one trial, a significant decrease in cortisol and malondialdehyde was reported in yoga participants as compared with controls. The mean difference was -5.5 μg/L (95%CI -7.1 to -4.0, p<0.00001) for cortisol and -16.6 nanomol/dl (95%CI -22.0 to -11.2, p<0.00001) for malondialdehyde in a random effect analysis.

Limitation: Meta-analysis was not conducted on psychosocial measurements due to limited trials measuring effect of yoga on this parameter. The trials were of low to medium risk. The duration of session per day was not detailed in the trials. Compliance rate of yoga among participants was not measurement in most of the trials. Though search has been done thoroughly but there can be articles which were missed. Medium of language was only English for the search criteria which may have limited identification of potential articles on yoga.

Clinical implications: This meta-analysis indicate that yoga

may be a potential complementary therapy for the management

of diabetes by improving glycemic control, serum lipid profiles,

increasing quality of life, reducing oxidative stress. However,

future larger randomized controlled trial should be conducted

with customised yoga for diabetes, applying robust methodology

and measuring long-term effect of yoga. Since the beginning of 20th

century, yoga has gained popularity around the globe [36]. Though

originated from India, it is also widely accepted in the western

countries. During the course of time, yoga postures must have been

customized according to the need of practitioners. Thus, variety of

forms of yoga such as, hatha yoga, Iyengar yoga, Sudarshan kriya

yoga, vinyasa yoga, bikram yoga etc are available in yoga centers.

Thus, the studies are conducted using different style of yoga with

combination of pranayama and meditation. This gives rise to

heterogeneity and nonconclusive results among studies. Population,

style of yoga, duration of yoga differs from study to study. It is highly

recommended that future studies should be done with more focus

on the style of yoga, duration of yoga and population to which

it is applied. Sudarshan kriya yoga is a combination of asanas, pranayama and kriya involving cyclic repeating breathing pattern

with a few moments of holding the breath. This pattern is found to

be more beneficial in calming the mind thus reducing stress, anxiety

and depression.[5,37,38] while bikram yoga is a set of 26 asanas,

standing pranayama, floor asanas and savasanas performed in a

constant heat of 40° Celsius and 40% humidity [39], Iyengar yoga is

more focused on asanas and breathing with supporting equipments

of duration 90 min[40]. Majority of the studies are done on Indian

population and the similar effect on other population needs

evaluation. Ethnic disparities exist in diabetes either in biological

or non-biological factors. [41]. South Asians have a low prevelance

of overall obesity but yet increased abdominal adiposity, insulin

resistance and reduced insulin sensitivity is high as compared with

several other ethnic groups [41]. Future larger randomized trial

should consider all these pointers while designing the study with

Conclusion

Results from this meta-analysis indicate that yoga can be a potential adjuvant therapy for the management of T2DM. However, further larger randomized controlled trials are required to corrobate the effect of yoga on psychological aspects and other health parameters considering the limitations.

Authors Contribution

RS designed the protocol and wrote the manuscript. AB reviewed the protocol and manuscript critically. JT reviewed the manuscript critically. All authors have read and approved the manuscript.

Acknowledgment

We are grateful to Kuwait Foundation for the Advancement of Scienes (KFAS) for the financial support. Grant # RA 2014-028.

Conflict of Interest

No conflict of interest.

References

- International Diabetes Federation (2019) IDF Diabetes Atlas, (9th edn). Brussels, Belgium.

- Posadzki P, MS Lee, E Ernst (2012) Complementary and alternative medicine for diabetes mellitus: an overview of systematic reviews. Focus Altern and Compl Ther 17(3): 142-148

- Clarke TC (2018) Use of Yoga, Meditation, and Chiropractors Among U.S. Adults Aged 18 and Over. NCHS Data Brief 325:1-8.

- Mary TQuilty RB, Richard Goldstein, Sat Bir S Khalsa (2013) Yoga in the real world: perceptions, motivators, barriers and patterns of use. Glob Adv Health Med 2(1): 44-49.

- Brown RP, PL Gerbarg (2005) Sudarshan Kriya Yogic breathing in the treatment of stress, anxiety, and depression. Part II--clinical applications and guidelines. J Altern Complement Med 11(4): 711-717.

- Brown RP, PL Gerbarg (2005) Sudarshan Kriya yogic breathing in the treatment of stress, anxiety, and depression: part I-neurophysiologic model. J Altern Complement Med 11(1): 189-201.

- Dhikav V (2010) Yoga in male sexual functioning: a noncompararive pilot study. J Sex Med 7(10): 3460-3466.

- Kyizom T (2010) Effect of pranayama & yoga-asana on cognitive brain functions in type 2 diabetes-P3 event related evoked potential (ERP). Indian J Med Res 131: 636-640.

- Kothari TO (2019) Prospective randomized trial of standard antiemetic therapy with yoga versus standard antiemetic therapy alone for highly emetogenic chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting in South Asian population. J Cancer Res Ther 15(5): 1120-1123.

- Yonglitthipagon P (2017) Effect of yoga on the menstrual pain, physical fitness, and quality of life of young women with primary dysmenorrhea. J Bodyw Mov Ther 21(4): 840-846.

- Neyaz O (2019) Effectiveness of Hatha Yoga Versus Conventional Therapeutic Exercises for Chronic Nonspecific Low-Back Pain. J Altern Complement Med 25(9): 938-945.

- McCall MC (2013) How might yoga work? An overview of potential underlying mechanisms. J yoga phys ther 3(1).

- Halpern J (2014) Yoga for improving sleep quality and quality of life for older adults. Altern Ther Health Med 20(3): 37-46.

- Vera FM (2009) Subjective Sleep Quality and hormonal modulation in long-term yoga practitioners. Biol Psychol 81(3): 164-168.

- Kosuri M, GR Sridhar (2009) Yoga practice in diabetes improves physical and psychological outcomes. Metab Syndr Relat Disord 7(6): 515-517.

- Hegde SV (2013) Effect of community-based yoga intervention on oxidative stress and glycemic parameters in prediabetes: a randomized controlled trial. Complement Ther Med 21(6): 571-576.

- Hegde SV (2011) Effect of 3-month yoga on oxidative stress in type 2 diabetes with or without complications: a controlled clinical trial. Diabetes Care 34(10): 2208-2210.

- Jyotsna VP (2014) Completion report: Effect of Comprehensive Yogic Breathing program on type 2 diabetes: A randomized control trial. Indian J Endocrinol Metab 18(4): 582-584.

- Mc Dermott KA (2014) A yoga intervention for type 2 diabetes risk reduction: a pilot randomized controlled trial. BMC Complement Altern Med 14: 212.

- Nagarathna R (2012) Efficacy of yoga-based lifestyle modification program on medication score and lipid profile in type 2 diabetes-a randomized control study. Int J Diabetes Dev Countries 32(3):122-130.

- Shantakumari N, S Sequeira, R El deeb (2013) Effects of a yoga intervention on lipid profiles of diabetes patients with dyslipidemia. Indian Heart J 65(2): 127-131.

- Singh S (2008) Influence of pranayamas and yoga-asanas on serum insulin, blood glucose and lipid profile in type 2 diabetes. Indian J Clin Biochem 23(4): 365-368.

- Yang K (2011) Utilization of 3-month yoga program for adults at high risk for type 2 diabetes: a pilot study. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med 2011: 257891.

- Beena RK, E Sreekumaran (2013) Yogic practice and diabetes mellitus in geriatric patients. Int J Yoga 6(1): 47-54.

- Innes KE, HK Vincent (2007) The influence of yoga-based programs on risk profiles in adults with type 2 diabetes mellitus: a systematic review. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med 4(4): 469-486.

- Aljasir B, M Bryson, B Al Shehri (2010) Yoga Practice for the Management of Type II Diabetes Mellitus in Adults: A systematic review. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med 7(4): 399-408.

- Herpreet Thinda, Ryan Lantinib, Brittany L Ballettob, Marissa L Donahueb, Elena Salmoirago Blotcherb, et al. (2017) The effects of yoga among adults with type 2 diabetes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Prev Med 105: 116-126.

- Divya Sivaramakrishnan, CF, Paul Kelly, Kim Ludwig, Nanette Mutrie (2019) The effects of yoga compared to active and inactive controls on physical function and health related quality of life in older adults systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Int J behav nutr Phys S Act 16(1): 33.

- Ramya Ramamoorthi, DG, Timothy Skinner, Simon Moss (2019) The effect of yoga practice on glycemic controland other health parameters in the prediabetic state: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One 14(10): e0221067.

- Higgins JPT (2011) SGe Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions version 5.1.0.

- Gordon LA (2008) Effect of exercise therapy on lipid profile and oxidative stress indicators in patients with type 2 diabetes. BMC Complement Altern Med 8: 21.

- Cui J (2017) Effects of yoga in adults with type 2 diabetes mellitus: A meta-analysis. J Diabetes Investig 8(2): 201-209.

- Kumar V (2016) Role of yoga for patients with type II diabetes mellitus: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Complement Ther Med 25: 104-112.

- Jayawardena R (2018) The benefits of yoga practice compared to physical exercise in the management of type 2 Diabetes Mellitus: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Diabetes Metab Syndr 12(5): 795-805.

- Vizcaino M, E Stover (2016) The effect of yoga practice on glycemic control and other health parameters in Type 2 diabetes mellitus patients: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Complement Ther Med 28: 57-66.

- Cramer H, LR Dobos G (2014) Characteristics of randomized controlled trials of yoga: a bibliometric analysis. BMC Complement Altern Med 14(3): 1-20.

- Zope SA, RA Zope (2013) Sudarshan kriya yoga: Breathing for health. Int J Yoga 6(1): 4-10.

- Shiju R (2019) Effect of Sudarshan Kriya Yoga on anxiety, depression, and quality of life in people with type 2 diabetes: A pilot study in Kuwait. Diabetes Metab Syndr 13(3): 1995-1999.

- Hewett ZL (2011) An Examination of the Effectiveness of an 8-week Bikram Yoga Program on Mindfulness, Perceived Stress, and Physical Fitness. Journal of Exercise Science & Fitness 9(2): 87-92.

- Streeter CC (2017) Treatment of Major Depressive Disorder with Iyengar Yoga and Coherent Breathing: A Randomized Controlled Dosing Study. Altern Complement Ther 23(6): 236-243.

- Spanakis EK, SH Golden (2013) Race/ethnic difference in diabetes and diabetic complications. Curr Diab Rep 13(6): 814-823.

-

Rashmi S, Monira Al A, Jaakko T, Abdullah B. Yoga and Its Effect on Glycemic Control and Oxidative Stress in People with Type 2 Diabetes in A Randomized Trial: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. W J Yoga Phys Ther & Rehabil 2(2): 2020. WJYPR.MS.ID.000531.

-

Yoga, Glycemic control, Stress, Metaanalysis, Complementary, Alternative medicine, Diabetes mellitus, Disease, Pharmacological

-

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.