Research Article

Research Article

Physiotherapy Students Perceptions and Experiences

Regarding the Psychological Content of ACL

Rehabilitation.

Jo Ann Kaye1*, Emma Duffy2 and Jenny Alexanders3

1School of Health and Social Care, Campus Heart, Teesside University, Middlesborough, UK

2School of Health and Social Care, Campus Heart, Teesside University, Middlesborough, UK

3School of Health and Social Care, Campus Heart, Teesside University, Middlesborough, UK

Jo Ann Kaye1*, Emma Duffy2 and Jenny Alexanders3

1School of Health and Social Care, Campus Heart, Teesside University, Middlesborough, UK

2School of Health and Social Care, Campus Heart, Teesside University, Middlesborough, UK

3School of Health and Social Care, Campus Heart, Teesside University, Middlesborough, UK

Jo Ann Kaye, School of Health and Social Care, Campus Heart, Teesside University, Middlesborough, UK.

Received Date: February 10, 2023; Published Date:March 03, 2023

Abstract

Purpose: Addressing the psychological needs of the patient during Anterior Cruciate Ligament (ACL) rehabilitation is of paramount importance to enhance recovery. Despite this, research investigating the psychological education of physiotherapy students continues to be under analysed. Therefore, the aim of this study was to explore physiotherapy student’s perceptions and experiences regarding the psychological content of ACL rehabilitation.

Method: An inductive approach through purposive sampling was used. Semi-structured interviews were conducted investigating student physiotherapists understanding and experience in addressing psychological aspects/needs within ACL rehabilitation. Data analysis included thematic analysis.

Results: Participants demonstrated some understanding of psychological interventions however it was evident that the application of these approaches were lacking. Four main themes were identified in the current study: Understanding, Experiences, Training and Training needs.

Discussion: The application of psychological approaches was clearly minimal from not only students formal training at University but also during their clinical placements. This is in line with the literature showing an insufficient amount of psychology training in UK physiotherapy degrees.

Conclusion: Psychology education within UK physiotherapy programmes needs to be given a stronger platform to better equip students preparing for practice. Future research determining whether physiotherapy curriculums include psychology modules and to what those modules contain may provide valuable insight.

Introduction

More recently, sport participation including people of all ages has increased as well as higher intensity and physical demands of sport [1]. From a physiotherapy perspective, the process of rehabilitation has historically been perceived as merely physical in nature [2]. The Chartered Society of Physiotherapy (CSP) stating; “Physiotherapy is a science-based profession and takes a ‘whole person’ approach to health and wellbeing, which includes the patient’s general lifestyle” [3]. Despite the CSP and the Health and Care Professions Council (HCPC) identifying the significance of psychological interventions within physiotherapy, information surrounding the current psychology content within UK universities remains under analysed. Evidence from Baez, et al. [4] and Cheney, et al. [5] both alluded that the psychological factors, specifically affecting rehabilitation outcomes following anterior cruciate ligament surgery, have been underestimated from the orthopaedic literature. Similarly, Forsdyke, et al. [6] concluded that the primary focus of recent research has been on the physical impact of ACL surgery and in absence of any psychosocial factors associated with this procedure. Corroborated with Burland, et al. [7], athletes return to sport criteria is based primarily on functional outcomes despite evidence suggesting it is multifactorial and largely influenced by psychological factors. Burland [7] advocates that clinician’s must combine physical and psychological interventions as part of an ACL rehabilitation programme to optimize recovery.

Within the past 30 years, there has been a significant growth in the number of rating systems and scales used as patient-reported outcome measures following ACL reconstruction and other specific knee conditions. Wang, et al. [8], identified 24 instruments used and examined their reliability and validity. Such measures include; Cincinnati Knee Rating System, The Lysholm Knee Score, the Knee Injury and Osteoarthritis outcome score (KOOS) and the International Knee Documentation Committee (IKDC). However, Wang et al suggests that none of these instruments are universally friendly and clinicians that want patient-based measurement scores will have to consider the population in which they are working with. Furthermore, Almangoush and Herrington [9] indicated that patient-reported outcomes measures in ACL rehabilitation are increasingly being used within the two decades and continues to gain traction. Correspondingly, functional performance tests such as the one-leg hop test and leg symmetry index (LSI) are two of the main parameters and good indicators of rehabilitation outcomes.

Central to dynamic joint stability of the knee is the anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) which operates as a ligamentous restraint to anterior translation of the tibia [10]. The ACL is the most commonly injured structure of the knee sustained on account of sports participation that primarily involves movements such as pivoting, jumping and/or a sudden deceleration [11]. In a recent study 88% of ACL injuries occurred without any impact where it was identified that non-contact injuries were as frequent as indirect contact injuries, in fact the most common cause was the action of kicking (Della Villa, et al.). It is important to consider multidimensional and multifactorial factors for ACL mechanism of injury occurrence in non-contact sports [12]. Walden has highlighted that the most common mechanism includes:deceleration with high knee internal extension torque collective with dynamic valgus rotation with the body weight shifted over the injured leg and the plantar surface of the foot fixed flat on the surface. As well as external non-contact risk factors can consist of: dry weather, artificial or uneven surface and common intrinsic risk factors include: knee joint laxity, small and narrow intercondylar notch width (ratio of notch width to the diameter and cross-sectional area of the ACL), hamstring strength recruitment, muscle fatigue, reduced core strength and proprioception, reduced knee hip and trunk flexion angles and increased dorsiflexion of the ankle whilst playing [12]. For ACL injuries, the mechanism of injury does not appear to be an isolated risk factor presenting in all cases of non-contact ACL injuries [12].

In light of the above, considerations of the psychological factors that may inhibit optimal return to sport of an athlete post ACL repair are important [13,14]. Ellman, et al. [15] indicated that although advances have been made regarding surgical techniques for ACL reconstruction, return to sport outcomes are influenced by both physical and psychological factors. Due to a lack of literature surrounding the importance of psychological interventions following ACL reconstruction, clinicians are largely guided by evidence with a prime focus on physical rehabilitation. Therefore, Ellman, et al. [15] concluded that there is a lack of criteria and guidelines directly related to the psychological state of an athlete that will subsequently guide their decision to return to sport.

It has been substantiated by numerous studies that psychological factors play a crucial role in post-operative ACL reconstruction return to play (King Chung Chan, 2017). Few studies however have focused on identifying the psychological aspects. Following ACL surgery, athletes have previously reported symptoms such as depression, lack of confidence, anxiety and fear of re-injury [16,17]. It has been proven that athletes struggle emotionally and psychologically following ACL reconstruction [18]. Albers further demonstrated the lack of current literature surround the psychosocial approach to rehabilitation following ACL reconstruction. As a result, clinicians have limited knowledge of psychology and therefore are unable to provide a multifactorial approach to rehabilitation [19]. An understanding surrounding the field of psychology may therefore be a fundamental component of physiotherapy practice which is reflected through current literature identifying its importance [20,16]. Areas of psychology including pain education, cognitive behavioral therapies (CBT), motivational interviewing and goal setting has been acknowledged in this domain since 2007, and received significant attention leading to a greater recognition of the biopsychosocial model rather than the biomedical model in physiotherapy [2].

Whilst recognition of these interventions has grown, physiotherapists have not fully accepted psychology resources in ACL rehabilitation [21]. Heaney, et al. [22] suggests this is due to lack of confidence or understanding to implement such interventions within their practice. Heaney, et al. [22] demonstrated that the use of psychological strategies in rehabilitation requires a diverse skillset and level of knowledge of which the majority of physiotherapists are not accustomed to. Findings correspond to a systematic review conducted by Alexanders, et al. [23] concluding that, although physiotherapists may be aware of the benefits of psychological interventions, musculoskeletal physiotherapists do not feel adequately trained to implement them into practice. In light of this, evidence has reported that physiotherapists are aware of the advantages of including psychological interventions within the rehabilitation process, yet physiotherapists do not feel adequately trained in the implementation of psychological interventions to enhance treatment outcomes [24,25,23].

In more recent years, Higgins and Gray [26] explored student physiotherapist’s attitudes towards the use of psychological interventions in general physiotherapy practice. The findings revealed that physiotherapy perceived barriers were the actual implementation of such strategies. Higgins and Gray [26], concluded there has been a lack of encouragement provided by practice educators around psychological interventions. This has also been substantiated across the globe with Ballengee, et al. [27] indicating the importance of psychology modules in physical therapy education and practice are somewhat minimal. Furthermore, evidence is lacking in relation to guiding universities on the best course of action to take when imbedding psychology education into the curriculum. Ballengee, et al. [27], argues that this could be due to psychological interventions being historically overlooked and undervalued by physical therapists in the US. Historical data from the Australian Journal of Science and Medicine in sport also indicates an ever-increasing implication to change the physiotherapy curriculum design with the addition of modules to improve psychological skills [28]. Therefore, it is clear, through recent and past historical evidence, that the global perspective surrounding the need for psychology modules within physiotherapy curriculums is crucial yet under-utilized.

Research incorporating psychological interventions as a preventative approach has started to gain some momentum. King- Chung Chang and Hagger [29] substantiated the importance of theoretical integration with particular focus on sports medicine, psychology and physiotherapy approaches combined. They suggest that using this approach using psychological theories to ultimately achieve a goal provides an increase in positive outcomes and can advance a clinicians’ understanding of effective rehabilitation. Furthermore, Dijkstra, et al. (2014) proposed a new Integrated Performance Health and Coaching model in sports medicine. This model encompasses theoretical integration and encourages a multidisciplinary team approach suggesting sports physicians should work closely with physiotherapists to ensure decisions are not made in isolation and medical evidence is utilized. Dijkstra et al (2014) advocated that without this approach “performance and psychological consequences” can arise. This infers that the integration of sports medicine, injury prevention, injury rehabilitation and psychological interventions are crucial when working with an athlete. This approach has been more recently evidenced by Gokeler et al [30] with direct reference to ACL rehabilitation. Their approach focused on motor learning and neuroplasticity in ACL rehabilitation and thus concluding how the integration of different approaches can lead to a more successful rehabilitation outcome.

As to date, there is no empirical evidence to give reason to the lack of psychological training within physiotherapy. There is a plethora of evidence highlighting the inconsistencies regarding the psychological content of physiotherapy programmes [31]. It is evident that physiotherapists do not feel confident implementing psychological interventions in rehabilitation due to a lack of training in university and clinical guidelines outlining criteria relevant to a psychosocial approach to rehabilitation (Riika et al. 2020). Therefore, the principle aim of this study was to explore physiotherapy student’s perceptions and experiences regarding the psychological content of ACL rehabilitation offered in their physiotherapy programme.

Methods

Before commencement of the interviews, this study received full ethical approval from Teesside University Ethics Committee on the 10th of October 2018 (See ethics approval letter in appendix).

Design

Data for this study was collected using semi-structured interviews. This form of data collection is instrumental in exploring the multidimensional nature of an individuals’ own perceptions and opinions (Parker, 2015). Thematic analysis was used to analyse the data from where an inductive approach was adopted. Through its theoretical stance, thematic analysis provides a flexible and insightful approach to qualitative data analysis (Braun & Clarke, 2006). Each interview ranged between thirty to forty-five minutes.

Participants

Participants for this research study were recruited from cohorts studying physiotherapy at Teesside University. A total of ten participants were selected to partake in the study in order to reach saturation levels [32]. This consisted of ten BSc and MSc physiotherapy students in Teesside University. Having a minimum of eight to ten participants reaches saturation, as proposed by Francis et al. (2010). Participants were eligible if they were over the age of 18, studying MSc or BSc physiotherapy in Teesside University and had experience regarding ACL rehabilitation (students must have conducted an musculoskeletal placement during the degree). Without relevant knowledge and experience such as MSK placements and previous experiences surrounding rehabilitation following ACL reconstruction, potential candidates would be excluded from the study. The table below shows the characteristics of the participants included in this study (Table 1).

Table 1:

Procedure

The invitations inviting participants to take part in the study were sent electronically via email to all MSc and BSc physiotherapy students in Teesside University. A participant information sheet comprising of the aims, methods, risks and benefits of the study was provided for the purpose of allowing the potential participants to make an informed decision on whether to take part in this study. A consent form and the details of the researcher and the supervisor of the research study was also provided if students had any concerns or questions regarding the study. Initially, the interview was piloted to a student selected at random for the purpose of allowing changes and rephrasing to be made.

Interviews were conducted face to face at an agreeable time and location within Teesside University. All interviews were undertaken during a three-week period. Each participant was given a number to ensure anonymity and confidentiality which in turn governed the order of the interviews. On commencing each interview, the participant was asked by the researcher to sign a written consent form and to verbally confirm their consent. A Dictaphone was used to record each interview with verbal and written consent gained from the participant.

Analysis

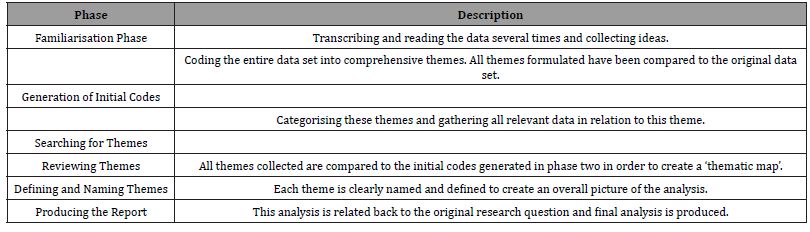

Using an inductive approach allows for themes to emerge through interpretation of the data (Thomas, 2006). An inductive approach was used in this study as it is a predominantly datadriven approach to qualitative research (Braun and Clarke, 2006). All interviews were transcribed verbatim. Transcripts were sent to each participant to confirm articulations. Data obtained throughout the entirety of the study was stored on a Teesside University password encrypted computer in accordance with the data protection act (Data Protection Act 1998). The processes performed in analysing the study followed Braun and Clarke’s (2006) method as seen in the 2 table below. The main researcher ED lead the main steps following Braun and Clarkes (2006) method which was then double checked by corresponding researchers JK and JA.

Confidentially will be maintained through anonymization to meet GPDR (2018). All participants were allocated a pseudonym (fictitious name) that used throughout the research in place of their correct name. Records connecting pseudonyms to participants was stored separately from the data itself. Once the interview had been transcribed, the audio files of the interviews were destroyed. Any additional identifying information contained within the interview transcripts (e.g.reference to places, employment etc.) was either removed or altered to protect participants identity. All interview transcripts and consent forms were stored securely as digital files on a personal University OneDrive account. This is a secure account on the University network, which only the research team (along with the University IT services in the case of an emergency) was able to access (Table 2).

Table 2:

Results

Four main themes were identified: Understanding, Experiences, Training and Training needs. The table below presents these themes in a structured framework that divides each theme into sub-themes with the purpose of giving meaning to the data that has emerged from this study (Figure 1). When asked about their level of understanding regarding psychological symptoms all students displayed an efficient awareness of the symptoms following ACL surgery and recognition of the importance of identifying these symptoms throughout recovery with one such candidate stating “I think one of the main symptoms I’ve noticed is low mood and fear of returning to their chosen sport. You can also notice when an athlete feels their identity has changed and they are no longer part of a team”.

When asked about their awareness surrounding psychological interventions that can be implemented into practice, it became evident that there was a lack of knowledge around these interventions which can be acknowledged in appendix 1.2. “Of the top of my head I don’t think I could tell you any interventions as would be able to use, from a psychological point of view of course”.

The results revealed that although students showed a broad understanding surrounding psychological symptoms following ACL surgery, very little knowledge was displayed on the potential psychological interventions that can be used throughout treatment. In relation to a physiotherapists’ scope of practice, it was demonstrated, throughout these discussions, that it is of popular believe that it is within a physiotherapists role to treat the psychological effects alongside the physical effects of ACL surgery. Christino, et al. [32] study postulated that understanding an athlete’s response to ACL injury is imperative for the purpose of improving recovery outcomes. Similarly, the findings from these studies were reflected within the current study were all students displayed an efficient understanding of the psychological symptoms following ACL surgery and an awareness of the importance of recognising these symptoms throughout recovery. Psychological symptoms are prominent throughout ACL recovery and therefore have an effect on the overall progression and outcome of treatment [33].

The current results indicate that, despite understanding psychological symptoms, the majority of students possess limited knowledge surrounding the psychological interventions that can be implemented throughout ACL rehabilitation. It been acknowledged there should be cognitive training before initiating with movement retraining [34] which highlights the significance of incorporating cognitive training and using psychological modalities. In light of this, some students discussed goal setting being used as a psychological intervention. These students appeared unable to discuss further alternative interventions. It has been empirically proven in a review by Reese et al [16] that goal setting alone is not a sufficient psychological intervention and must be used in conjunction with other approaches such as motivational interviewing and imagery. In addition, this review indicated that the implementation of these psychological interventions reduces negative psychological responses to injury. This evidence substantiates the importance of sport psychology following ACL surgery. The result of the present study suggests an inadequacy of knowledge around the psychological interventions used in ACL rehabilitation, therefore underpinning a need for an increased awareness and knowledge base for students. Which is in-line with literature suggests that UK Chartered physiotherapists also believe it is within their scope of practice to implement psychological interventions into treatment [36].

Experiences (main theme)

All participants were asked about their ACL placement experiences and what form of rehabilitation they observed. Some participants commented on group ACL classes with little no psychological interventions included (appendix 2.1). One student indicated the use of goal setting throughout their placement experiences “During my MSK placement, I remember my educator using goal settings with his patients particularly for the people who had just underwent ACL reconstruction, it was very interesting”. This intervention was not used in conjunction with alternative approaches which can be seen in appendix 2.2. Two other students discussed general empathy being used throughout treatment whilst indicating the absence of a specific framework to follow in relation to psychological interventions “I had an educator on placement who was very good at showing empathy and understanding and I could see the difference that made for the athlete and how this in itself could change the entire course of their rehab, just through understanding them and their journey”(Table 3,4,5).

Table 3:

Table 4:

Table 5:

Current literature has identified several important psychological interventions used by physiotherapists in practice such as mental imagery, goal setting, cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), motivational interviewing and positive self-talk [23]. A systematic review, conducted by Driver, et al. [37], demonstrated the importance of psychological interventions particularly for the treatment of chronic pain and ACL rehabilitation. Goal setting and motivational interviewing appeared to be the most common interventions used within physiotherapy practice. This review reported limited use of further interventions such as mental imagery and CBT. Hamson-Utley, et al. [38] speculates that these techniques are under-utilized in practice due to a lack of understanding and knowledge. This suggests a disparity regarding the use of psychological interventions within physiotherapy practice. All students in this study discussed completing a musculoskeletal placement where they had treated patients following ACL surgery. Despite similar experiences iterated, the overall discussions were troubling. The majority of students indicated that they had not observed any psychological interventions being implemented into practice by qualified physiotherapists when treating post-operative ACL patients. Moreover, it has been taken into consideration that all physiotherapists will vary throughout practice and different interventions will be employed. Despite this, contemporary literature emphasises the discussions undertaken within the present study and gives reason as to why student physiotherapists have observed limited psychological interventions during their clinical placements.

Training (main theme)

Most participants of this study felt their training in sport psychology and psychological interventions was minimal (appendix 3.3). One such student stated, “I’m in my final year of physiotherapy and I don’t remember one class or lecturer teaching us about psychological interventions in physio. It has definitely been mentioned, but nobody has ever delved into it in Uni”. Another candidate reported, “Psychological interventions have been spoken about really intermittently in class but none of our lecturers have ever thought us how to bring this into practice with us, I feel I’m going in blind as far as a psychological approach goes”.

The amount of psychological training received in both MSc and BSc physiotherapy programmes appeared inadequate. The majority of students felt their training in sport psychology and the implementation of psychological interventions was minimal and throughout the present study, it appears that psychological training has yet to evolve in physiotherapy programmes across UK universities [39]. Correspondingly, there is limited empirical evidence investigating the psychology content of these programmes. Although literature substantiating the importance of psychology in physiotherapy can be traced back as far as the late 1980’s, the physiotherapy profession continued to use the medical model of healthcare [40]. More contemporary research, carried out by Heaney et al [22], investigated the psychology content of UK universities and alluded that there is an inconsistency between physiotherapy programmes across the UK [43-48]. Despite all institutions included in this study stating they incorporated an element of psychology within physiotherapy, only 23.5% of universities dedicated a module directly to sport psychology. The remaining percentage of universities integrated sport psychology and overall psychological training within other modules [49-52]. This study also highlighted the need for further research to be conducted to establish whether or not the psychology content with physiotherapy curriculums has changed since. There is a lack of evidence to illustrate how these curriculums are delivered in university [53-59].

Training needs (main theme)

Participants of this study discussed the potential training needs for both qualified and student physiotherapists some of which indicated the need for a module directly focusing on psychological interventions and how to implement them (appedix 4.1). One student stated, “I think we need a full module on psychology to be honest, otherwise how are we ever really going to implement a psychological approach once we qualify”. Another student reported, “I think the lecturers themselves need to learn more on the topic. They don’t teach us psychological interventions because maybe they just don’t know how to”. This is significant to note, if lecturers are not implemented these strategies in their university teaching, although the evidence is suggesting integrating psychological interventions enhances rehabilitation, students are not learning how to efficiently and effectively implement these strategies for when they qualify.

Student physiotherapists discussed the potential training needs for both qualified and student physiotherapists. Despite reporting a module focusing on healthcare models including the biopsychosocial model, the majority of students again highlighted that there was no module dedicated to sport psychology within the physiotherapy curriculum. Therefore, these students indicated the need for a module directly focusing on the training of psychological interventions. Scott (2016) proposed that assessment and feedback can improve overall outcomes and also boost a student’s confidence. Research by Cormier and Zizzi (2015) identified athletic trainers had a strong understanding and felt competent in applying a biopsychosocial model, yet unfelt underprepared when implementing to practice [60-62]. A number of students identified the need for qualified physiotherapists to receive ongoing continued professional development (CPD) in sport psychology. Two students suggested a psychological framework to help physiotherapists in the implementation of psychological interventions in practice. When considering this research alongside the evidence above it is clear there is a disconnect between what physiotherapist students should be taught based on the evidence base and what is actually being taught in universities.

Conclusion

An important consideration by participants of this study was the need for students to have a psychology module that is assessed in order to optimize learning outcomes. In order to attain CSP accreditation, physiotherapy programmes must provide psychological training (CSP, 2002). Despite this, the most recent investigation of the psychology content in UK physiotherapy degrees postulated that whilst these degrees provide psychological training there remains a lack of knowledge on its present status suggesting a discrepancy surrounding the amount of training provided to students (Heaney, 2012). Student physiotherapists that participated in this study highlighted the lack of training, understanding and skill when treating an individual with psychological tools during ACL rehabilitation. Moreover, student physiotherapists demonstrated a good understanding of the importance of psychological interventions but a poor level of understanding regarding the implementation of any psychological interventions as a direct result from an insufficient amount of training. In order to determine the level of psychological training received within UK universities to qualified physiotherapists on this topic, a comprehensive review and analysis of the psychological content incorporated into physiotherapy programmes is required. Despite this study’s inability to shed light on the amount of psychological training in physiotherapy available across all universities in the UK, it can potentially raise awareness of this inadequacy as the results from this current study highlighted the lack of psychological training in one said University [62-64]. Furthermore, the numerous of evidence presented in this study surrounding physiotherapist’s lack of knowledge on psychological approaches to ACL rehabilitation across the UK suggests a need for a more in-depth module be provided at undergraduate and postgraduate level. Future research may benefit from interviewing clinical supervisors on the quality of the education in physiotherapy.

Acknowledgment

None.

Conflict of Interest

No conflict of interest.

References

- Deshmukh VY (2019) Injuries in Sport. Inernaional Interdisciplinary Research Journal.

- Beneka A (2007) Appropriate counselling techniques for specific components of the rehabilitation plan: a review of literature. Department of Physical Education & Sport Science.

- CSP (2019) What is physiotherapy?

- Baez SE, Hoch MC, Hoch JM (2019) Psychological factors are associated with return to pre-injury levels of sport and physical activity after ACL reconstruction. Knee Surgery, Sports Traumatology, Arthroscopy.

- Cheney S, Chiaia TA, De Mille P, Boyle C, Ling D (2020) Readiness to Return to Sport After ACL Reconstruction. Sports Medicine and Arthroscopy Review 28(2): 66-70.

- Forsdyke D, Smith A, Jones M, Adam Gledhill (2016) Psychosocial factors associated with outcomes of sports injury rehabilitation in competitive athletes: a mixed studies systematic review. British Journal of Sports Medicine 50(9): 537-544.

- Burland JP, Julie P Burland, Jenny Toonstra, Jennifer L Werner, Carl G Mattacola, et al. (2018) Decision to return to sport after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction, Part I: A Qualitative Investigation of Psychosocial Factors. J Athl Train 53(5): 452-463.

- Wang Dean, Morgan H Jones, Mahmoud M Khair, Anthony Miniaci (2010) Patient-reported outcome measures for the Knee. J Knee Surg 23(3): 137-152.

- Almangoush, Herrington (2014) Functional Performance Testing and Patient Reported Outcomes following ACL Reconstruction: A Systematic Scoping Review. Int Sch Res Notice Article. ID 613034.

- Hewett TE, Stephanie L Di Stasi, Gregory D Myer (2013) Current concepts for injury prevention in athletes after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Am J Sports Med 41(1): 216-24.

- Imran A (2020) Analysis of Anterior Cruciate Ligament of the Human Knee Using a Mathematical Model. Advances in Lightweight Materials and Structures pp 801-806.

- Walden M, Tron Krosshaug, John Bjørneboe, Thor Einar Andersen, Oliver Faul, et al. (2015) Three distinct mechanisms predominate in noncontact anterior cruciate ligament injuries in male professional football players: A systematic video analysis of 39 cases. British Journal of Sports Medicine 49(22): 1452-1460.

- Hart HF, Culvenor AG, Guermazi A, Crossley KM (2019) Worse knee confidence, fear of movement, psychological readiness to return-to-sport and pain are associated with worse function after ACL reconstruction. Physical Therapy in Sport 41: 1-8.

- Kitaguchi T, Takuya Kitaguchi, Yoshinari Tanaka, Shinya Takeshita, Nozomi Tsujimoto, Keisuke Kita, et al. (2020) Importance of functional performance and psychological readiness for return to preinjury level of sports 1 year after ACL reconstruction in competitive athletes. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 28(7): 2203-2212.

- Michael B Ellman, Seth L Sherman, Brian Forsythe, Robert F LaPrade, Brian J Cole, et al. (2015) Return to play following anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Journal of the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons 23(5): 283-296.

- Reese LMS (2012) Effectiveness of psychological intervention following sport injury. (1): 71-79.

- Arden CL, et al. (2015) Psychological Aspects of Anterior Cruciate Ligament Injuries. 24(1): 77-83.

- Alber S (2020) Psychological consequences of athletic injury and the necessity of psychological support during rehabilitation and return to sport transition: An examination from a self-determination perspective.

- Zarsycki R, Arden C (2020) Psychological aspects in return to sport following ACL reconstruction. Basketball Sports Medicine and Science pp 1005-1013.

- Christino MA, Braden C Fleming, Jason T Machan, Robert M Shalvoy (2016) Psychological factors associated with anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction recovery. Orthop J Sports Med 4(3): 2325967116638341.

- D, Michael Callaghan, Carianne Hunt, Michelle Briggs, Jane Griffiths (2019) Psychologically informed approaches to chronic low back pain: Exploring musculoskeletal physiotherapists' attitudes and beliefs. Musculoskeletal care 17(2): 272-276.

- Heaney C (2012) A Qualitative and Quantitative Investigation of the Psychology Content of UK Physiotherapy Education Programs. Vol 26, Issue 3.

- Alexanders J, Anna Anderson, Sarah Henderson (2015) Musculoskeletal physiotherapist’s use of psychological interventions: a systematic review of therapist’s perceptions and practice. Physiotherapy 101(2): 95-102.

- Ninedek A, Kolt GS (2000) Sport Physiotherapists' Perceptions of Psychological Strategies in Sport Injury Rehabilitation. 9: 191-206.

- B Hemmings, L Povey (2002) Content of their practice: a preliminary study in the United Kingdom. Br J Sport Med 36(1): 61-64.

- Higgins R, Gray H (2020) Barriers and facilitators to student physiotherapists’ use of psychological interventions in physiotherapy practice.

- Ballengee LA, Covington JK, George SZ (2020) Introduction of a psychologically informed educational intervention for pre-licensure physical therapists in a classroom setting. BMC Med Educ 20(1): 382.

- Ford IW, Gordon S (1997) Perspectives of sport physiotherapists on the frequency and significance of psychological factors in professional practice: implications for curriculum design in professional training. Australian Journal of Science and Medicine in Sport 29(2): 34-40.

- Chan DKC, Hagger MS (2012) Theoretical Integration and the Psychology of Sport Injury Prevention. Sports Med 42(9): 725-732.

- Alli Gokeler, Dorothee Neuhaus, Anne Benjaminse, Dustin R Grooms, Jochen Baumeister (2019) Principles of Motor Learning to Support Neuroplasticity After ACL Injury: Implications for Optimizing Performance and Reducing Risk of Second ACL Injury. Sports Med 49(6): 853-865.

- Annear A, Sole G, Devan H (2019) What are the current practices of sports physiotherapists in integrating psychological strategies during athletes’ return-to-play rehabilitation? Mixed methods systematic review. Physical Therapy in Sport 38: 96-105.

- Latham JR (2013) A framework for leading the transformation to performance excellence part I: CEO perspectives on forces, facilitators, and strategic leadership systems. Quality Management Journal 20(2): 22.

- Christino MA, Braden C Fleming, Jason T Machan, Robert M Shalvoy (2016) Psychological factors associated with anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction recovery. Orthop J Sports Med 4(3): 2325967116638341.

- Brewer BW (2010) The role of psychological factors in sport injury rehabilitation outcomes. 3(1): 40-61.

- Noehren B, Kline P, Ireland ML, Johnson DL (2017) ‘Kinesiophobia is strongly associated with altered loading after an ACL reconstruction: implications for re-injury risk’. Orthopaedic Journal of Sports Medicine. 5(7) (suppl 6).

- Arvinen-Barrow M, et al. (2009) UK chartered physiotherapists’ personal experiences in using psychological interventions with injured athletes: An Interpretative Phenomenological Analysis. (11): 58-66.

- Driver C, Bridie Kean, Florin Oprescu, Geoff P Lovell (2017) Knowledge, behaviors, attitudes and beliefs of physiotherapists towards the use of psychological interventions in physiotherapy practice: a systematic review. 39(22): 2237-2249.

- Hamson-Utley JJ, Scott Martin, Jason Walters (2008) Athletic trainers' and physical therapists' perceptions of the effectiveness of psychological skills within sport injury rehabilitation programs. J Athl Train 43(3):258-64.

- Driver C, Lovell GP, Oprescu F (2021) Psychosocial strategies for physiotherapy: A qualitative examination of physiotherapist’s reported training preferences. Nursing & Health Sciences. 23(1): 136-147.

- Baddeley H, Bithell C (1989) Psychology in the physiotherapy curriculum: a survey. 75(1): 17-21.

- Arden CL, Kate E Webster, Nicholas F Taylor, Julian A Feller (2011) Return to sport following anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction surgery: a systematic review and meta-analysis of the state of play. Br J Sports Med 45(7): 596-606.

- Arden CL et al. (2011) Return to the preinjury level of competitive sport after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction surgery: two-thirds of patients have not returned by 12 months after surgery. 39(3): 538-43.

- Arden CL, Nicholas F Taylor, Julian A Feller, Timothy S Whitehead, Kate E Webster (2013) Psychological responses matter in returning to preinjury level of sport after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction surgery. Am J Sports Med 41(7):1549-58.

- Chin C, Osborne J (2008) Student's questions: a potential resource for teaching and learning science. Pages 1-39.

- Cormier ML, Zizzi SJ (2015) ‘Athletic Trainers’ Skills in Identifying and Managing Athletes Experiencing Psychological Distress’. Journal of Athletic Training 50(12): 1267-1276.

- CSP (2002) Curriculum Framework for Qualifying Programmes in Physiotherapy.

- CSP (2018) Musculoskeletal core capabilities framework for first point of contact practitioners.

- Driver C, Lovell GP, Oprescu F (2021) Psychosocial strategies for physiotherapy: A qualitative examination of physiotherapist’s reported training preferences. Nursing & Health Sciences. 23(1): 136-147.

- Engel GL (1977) The need for a new medical model: a challenge for biomedicine. Science 196(4286): 129-136.

- HCPC (2018) The standards of proficiency for physiotherapists.

- Hemmings B, Povey L (2002) Views of chartered physiotherapists on the psychological. Br J Sports Med 36(1): 61-64.

- Horibe S, Takuya Kitaguchi, Yoshinari Tanaka, Shinya Takeshita, Nozomi Tsujimoto, Keisuke Kita, et al. (2019) Importance of functional performance and psychological readiness for return to preinjury level of sports 1 year after ACL reconstruction in competitive athletes. Knee Surgery, Sports Traumatology, Arthroscopy 28(7): 2202-2212.

- Podlog L, Eklund RC (2005) Return to Sport after Serious Injury: A Retrospective Examination of Motivation and Psychological Outcomes. 14: 20-34.

- Scherzer CB, et al. (2001) Psychological Skills and Adherence to Rehabilitation after Reconstruction of the Anterior Cruciate Ligament. 10: 165-172.

- Scott GW (2016) Active engagement with assessment and feedback can improve group-work outcomes and boost student confidence. 2(1): 1-13.

- Smith F, E A Rosenlund, A K Aune, J A MacLean, S W Hillis (2004) Subjective functional assessments and the return to competitive sport after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Br J Sport Med 38(3): 279-284.

- Turk DC (2014) Psychological interventions. Practical management of pain. Fifth edition.

- Watson AWS (2013) Sports injuries: incidence, causes and prevention. 2(3): 135-151.

- Webb JM, I S Corry, A J Clingeleffer, L A Pinczewski (1998) Endoscopic reconstruction for isolated anterior cruciate ligament rupture. J Bone Joint Surg Br 80(2):288-94.

- Webster KE, Feller JA (2018) Return to Level I Sports After Anterior Cruciate Ligament Reconstruction: Evaluation of Age, Sex, and Readiness to Return Criteria. Orthop J Sports Med 6(8): 2325967118788045.

- Webster KE, jullian A Feller, christina Lambros (2007) Development and preliminary validation of a scale to measure the psychological impact of returning to sport following anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction surgery. Phys Ther Sport Pp: 9-15.

- WHO (2002) Towards a common language for functioning, disability and health.

- Zaffagnini S, Alberto Grassi, Margherita Serra, Maurilio Marcacci (2015) Return to sport after ACL reconstruction: how, when and why? A narrative review of current evidence. Joints 3(1): 25-30.

- Zielinksi J (2018) The impact of physical therapy on an athlete’s decision to return to sport.

-

Jo Ann Kaye*, Emma Duffy and Jenny Alexanders. Physiotherapy Students Perceptions and Experiences Regarding the Psychological Content of ACL Rehabilitation.. W J Yoga Phys Ther & Rehabil 3(4): 2023. WJYPR.MS.ID.000570.

-

Physiotherapy, ACL rehabilitation, Knee arthroplasty Psychological interventions, Chartered Society of Physiotherapy, Leg symmetry index, Musculoskeletal placement, Physiotherapists, Injury

-

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.