Case Report

Case Report

High Intensity Strengthening Following Total Knee

Arthroplasty Enabling Patient to Rapidly Exceed Age-

Related Functional Norms: A Case Report

Kyle R Adams1*, Jessica T Feda2 and Regine S Rossi3

1Department of Physical Therapy, Baylor University, Waco, TX, USA

2Department of Physical Therapy, Baylor University, Waco, TX, USA

3Department of Kinesiology, University of Connecticut, Storrs, CT, USA

Kyle R Adams1*, Jessica T Feda2 and Regine S Rossi3

1Department of Physical Therapy, Baylor University, Waco, TX, USA

2Department of Physical Therapy, Baylor University, Waco, TX, USA

3Department of Kinesiology, University of Connecticut, Storrs, CT, USA

Kyle R Adams, Department of Physical Therapy, Baylor University, Waco, TX, USA.

Received Date: December 12, 2022; Published Date:December 22, 2022

Abstract

Background and purpose

Total knee arthroplasty (TKA) is a commonly performed surgical procedure intended to decrease knee pain and improve function in individuals with knee osteoarthritis. Numerous studies highlight the benefit of high intensity strengthening on functional abilities following TKA. High intensity strengthening has the potential to provide a multitude of physiologic benefits, allowing for efficient and expedient return to function. Physical therapists commonly focus early post-operative TKA rehabilitation efforts on reducing pain and increasing range of motion (ROM) without enough emphasis on strengthening. This case report describes the use of high intensity strengthening to enable a rapid return to full function in a patient following total knee arthroplasty.

Case presentation

A previously sedentary 61-year-old male attended physical therapy two to three times a week for six weeks following TKA. The primary focus of treatment was high intensity strengthening and conditioning.

Outcomes

Following six weeks of physical therapy, functional outcome measures surpassed age-related norms. The patient’s lower extremity strength was symmetric bilaterally within six weeks of focused, progressive, high intensity strengthening.

Conclusion

High intensity strengthening and conditioning is a safe and effective means of returning patients to high levels of physical function following TKA. Clinical practice guidelines highlight the importance of high intensity strengthening status-post TKA; treatments should be regularly modified and progressed to return patients efficiently to age-related functional norms.

Keywords: Total knee arthroplasty; High intensity strengthening; Physical therapy; Post-operative rehabilitation; Progressive exercise

class="colorb">Abbreviation:TKA, Total knee arthroplasty; ROM, Range of motion; ADL, Activities of daily living; NPRS, Numerical pain rating scale; RPE, Rating of perceived exertion; RM, Repetition maximum; LEFS, Lower Extremity Functional Scale; KOS-ADLS, Knee Outcome Survey - Activities of Daily Living Scale; SF-36 PCS, Short Form 36-item Physical Component Summary; y/o, year old.

Introduction

Total knee arthroplasty (TKA) is a frequently performed surgical procedure intended to decrease knee pain and improve function in individuals with knee osteoarthritis [1]. However, six months after surgery, patients often continue to demonstrate significant strength and functional deficits compared to their peers [2-4]. Long-term deficits include an average of a 40% residual quadriceps strength impairment, a 30% decrease in six-minute walk test capacity, and a 110% increase in time to completion on the stair climbing test [5, 6]. Implementation of high intensity resistance training early after total knee arthroplasty is frequently discouraged due to concerns for increased joint effusion, pain, and delayed range of motion recovery [6-9]. Conversely, many studies support the benefit of high intensity strengthening on functional abilities following TKA [5, 6, 8,10-14], due to improvements in neuromuscular activation, [12, 15] and reduction in muscle atrophy [2, 13, 15-17]. A lack of awareness may contribute to the aforementioned sustained impairments and these deficits may result from the common belief that high intensity strengthening should wait until joint effusion, pain, and range of motion have improved.

Recent clinical practice guidelines further support high intensity strengthening status-post TKA [7, 16]. Physical therapists frequently focus early post-operative TKA rehabilitation efforts on reducing pain and increasing range of motion (ROM), de-emphasizing progressive, high intensity strengthening. This case report describes the use of strengthening activities to enable the return to optimal function following TKA in an overweight male avoidant of self-directed exercise and non-participatory in his home exercise program. High intensity strengthening provided an opportunity to return to prior activities and catapult him onto a functional path to recovery.

Case Presentation

The patient was a 61-year-old male with a history of osteoarthritis involving the left knee after a partial meniscectomy of his medial meniscus 30 years prior. He was six feet tall and weighed 220 pounds with a body mass index of 29.8. His past medical history was significant for hypertension and hypercholesterolemia, both well-controlled with medication. Prior to his TKA, he was limited in activities of daily living (ADL) due to significant knee pain and limited knee flexion range of motion (90 degrees). His significant range of motion loss, combined with self-reported nagging pain and weakness limited his ability to perform many of his cherished activities of daily living, such as working a full day, riding his motorcycle, and high-level jet skiing. Specific details regarding his pre-operative impairments were not available as he did not receive physical therapy prior to surgery. His goals for post-operative physical therapy encompassed a return to all activities without difficulty or pain.

The patient reported having a highly active lifestyle until six years prior to surgery. He conveyed he did not plan on exercising beyond physical therapy sessions and did not intend to continue exercising after his rehabilitation course. Although he was a previously active individual, he was not an active exerciser. We modified his rehabilitation protocol to help maximize in-session gains while consistently educating on the importance of regaining lower extremity strength to return to his desired activities, hopefully leaving a lasting impression on this patient regarding the value of high intensity strengthening and maintaining gains by staying active after his completion of supervised therapy.

After his total knee arthroplasty, the patient remained in the hospital for four days, followed by 14 days in a skilled nursing facility. Treatments consisted of ROM activities, low-level exercise, and ice, one to two times daily. Upon discharge from the skilled nursing facility, he waited two weeks before initiating outpatient physical therapy.

Treatment

He initiated outpatient physical therapy five weeks after his left TKA. At this time there were significant noted deficits in ROM, strength and function, therefore we initiated a plan of care encompassing physical therapy two to three times a week for six weeks. Each session lasted approximately 75 minutes in duration. During outpatient therapy, he was advised to perform a home exercise program consisting of aerobic exercise three times a week (walking or stationary cycling for 30-40 minutes), stretches once/day, and ROM activities one to two times a day; however, he did not comply with the home program.

Treatment sessions included interventions to progress range of motion (range of motion progression from passive to active) with a primary focus on high intensity strength training. His vital signs (blood pressure, pulse rate) were monitored before, during, and after treatments, pain levels were monitored using the numerical pain rating scale (NPRS), and the Borg rating of perceived exertion (RPE) scale was used during exercises to monitor his perceived level of activity [10, 18]. His vitals were consistently within safe ranges, and his Borg rating of perceived exertion (RPE) varied from 12-16 during strengthening [19, 20].

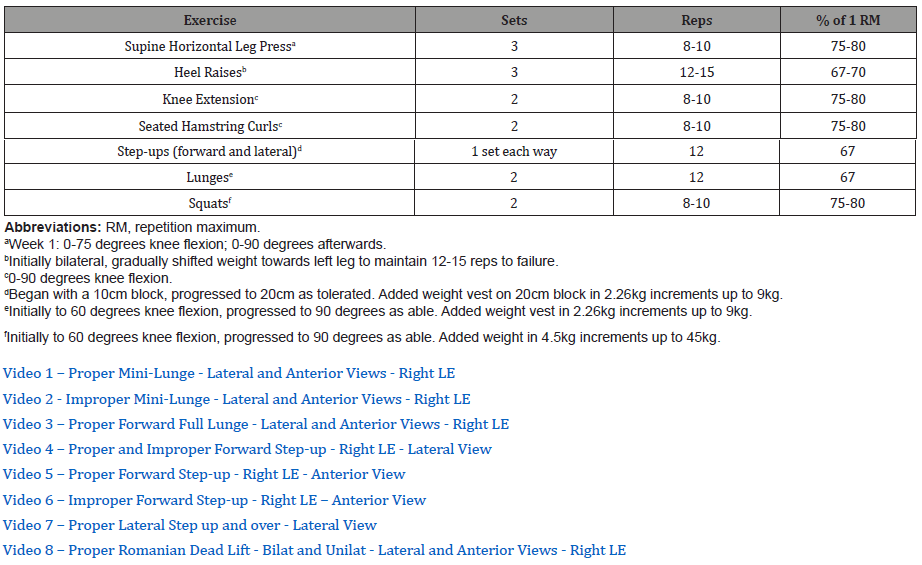

Importantly, the program was designed to fit specific performance- focused strength training principles. Strengthening exercises included supine horizontal leg press, standing heel raises, seated knee extension, seated hamstring curls, forward and lateral stepups, lunges, Romanian deadlifts, and squats (see Table 1).

Table 1:Strengthening Program.

The patient worked at intensities ranging from 67-80% of his one repetition maximum (RM) which has been shown to safely provide optimal strength gains in older adults [1, 12, 21, 22]. His 1RM was determined as a percentage of his demonstrated 10 RM which is shown to be reliable and valid [1, 12, 21, 22]. The progression strictly followed the 2-for-2 rule, with intensity increasing once the patient was able to perform two or more repetitions over his repetition goal in the last set of two consecutive workouts [23]. Finally, the patient was asked to adhere to prescriptions for tempo, with accelerated concentric movements to enhance power, [24, 25] as well as a pause at the end of the movement with subsequent controlled two-second eccentric movement to maximize strength improvements as suggested per age group [26].

Outcome and follow-up

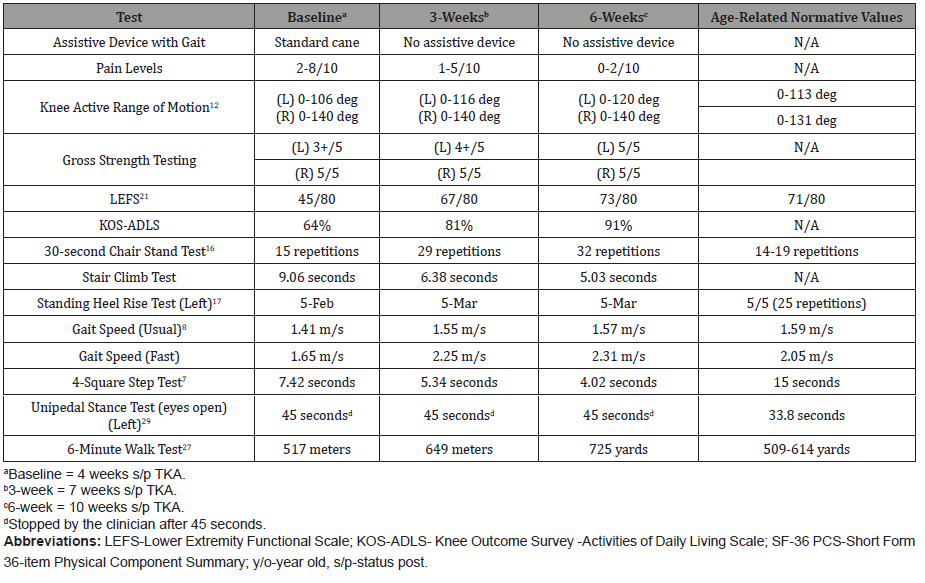

Outcome measures were repeated at three and six weeks. The patient’s strength and functional level demonstrated improvements following six weeks of physical therapy with an emphasis placed on high intensity strengthening. During the initial examination, his functional outcome scores (30-second Chair Stand Test, Gait Speed, six Minute Walk Test) were slightly below the normative values of age-related peers and his left lower extremity was significantly weaker during 10 RM testing (see Table 2). By the 3-week assessment his functional test scores were near or above age-related norms and by six weeks, functional measures were well above the normative values of his age-related peers, except for the standing heel rise assessment.

Table 2:Outcome Measurements and Scores.

Discussion

Outpatient physical therapy interventions focusing on high intensity strengthening following TKA in a patient who was admittedly unwilling to exercise outside of the clinic resulted in a rapid return to pain-free function. Within three weeks, the patient indicated his knee no longer felt stiff and he noticed he was able to walk efficiently without work or activity-related fatigue or pain. By the sixth week of high intensity strengthening, the patient reported that the strength in his left leg was no longer limiting him with daily activities and he had returned to his prior level of activity without pain, noting he had spent up to eight painless hours standing on multiple occasions without symptoms. Upon discharge, he noted, “I forgot that I had knee surgery until I returned home [from a long motorcycle ride]. My knee felt great!” During a follow-up phone call with his physical therapist two years after surgery, the patient reported that he was having no issues with his knee and had remained able to participate in all prior activities without limitation. He admitted he had not exercised since discontinuing physical therapy but believed the hard work during outpatient physical therapy was sufficient to enable him to return to all desired activities and an active daily lifestyle prevented regression.

It is worth acknowledging that the patient’s strength measures continued to improve at the same rate across the treatment period, while functional outcome measures demonstrated early gains and stabilized, perhaps due to the ceiling effects of the selected functional outcome tools. No adverse events were noted during treatment and the patient consistently attended physical therapy, despite his poor motivation towards self-directed exercise.

An inherent limitation of this case report is that cause and effect cannot be established. We cannot demonstrate a cause-and-effect relationship between the prescribed treatment and resultant positive outcomes. While the primary focus of treatment was intensive strengthening, other aspects of the patient’s treatment and daily activities could have contributed to the improved outcomes. With that being said, the outcome of this case report aligns with the abundance of evidence demonstrating the benefit of high intensity strengthening following TKA, [5, 6, 8,11-13, 16, 17, 27, 32] and the risk of persistent weakness and disability when appropriate strengthening is not included within a rehabilitative program [2-6].

In conclusion, a focus on high intensity strength training during TKA rehabilitation may not only decrease persistent strength and functional deficits following surgery, but was also shown here to prevent functional decline for a patient resistant to self-directed exercise after therapy intervention.

Learning points

• High intensity strengthening is a safe and effective method of improving recovery for patients after TKA.

• Strength training intensities should be progressively increased during various time points in post-operative recovery to accommodate gains achieved by the patient.

• High intensity strengthening fosters significant improvements in functional outcome measures and demonstrates extended improvements in strength.

Acknowledgement

The authors would like to thank Dr. Dale Avers, Associate Professor and Director of the Post-professional DPT program in the Program of Physical Therapy Education at Upstate Medical University, for providing guidance on early drafts of this case report.

Conflict of Interest

The authors report there are no competing interests to declare.

References

- Silver J, Caleshu C, Casson Parkin S, Ormond K (2018) Mindfulness among genetic counselors is associated with increased empathy and work engagement and decreased burnout and compassion fatigue. Journal of Genetic Counseling 27(5): 1175-1186.

- Morgan BM (2017) Stress management for college students: An experiential multi-modal approach. Journal of Creativity in Mental Health 12(3): 276-288.

- Heinz AJ (2021) Rising from the ashes by expanding access to community care after disaster: An origin story of the Wildfire Mental Health Collaborative and preliminary findings. Psychological Services.

- Aideyan B, Martin GC, Beeson ET (2020) A practitioner’s guide to breathwork in clinical mental health counseling. Journal of Mental Health Counseling 42(1): 78-94.

- Pittoello SR (2016) Exploring the contributions of a yoga practice to counsellor education. Canadian Journal of Counselling and Psychotherapy 50(2): 91-107.

- Thompson IA (2018) Luna Yoga: A wellness program for female counselors and counselors-in-training to foster self-awareness and connection. Journal of Creativity in Mental Health 13(2): 169-184.

- Christopher JC, Christopher SE, Dunnagan T, Schure M (2006) Teaching Self-Care Through Mindfulness Practices: The Application of Yoga, Meditation, and Qigong to Counselor Training. Journal of Humanistic Psychology 46(4): 494-509.

- Schure MB, Christopher J, Christopher S (2008) Mind-body medicine and the art of self-care: Teaching mindfulness to counseling students through yoga, meditation, and Qigong. Journal of Counseling & Development 86(1): 47-56.

- Campbell JC, Christopher JC (2012) Teaching mindfulness to create effective counselors. Journal of Mental Health Counseling, 34(3): 213-226.

- Maris JA (2009) The impact of a mind/body medicine class on counselor training: A personal journey. Journal of Humanistic Psychology 49(2): 229-235.

-

Adams KR, Feda JT, Rossi RS. High Intensity Strengthening Following Total Knee Arthroplasty Enabling Patient to Rapidly Exceed Age-Related Functional Norms: A Case Report. W J Yoga Phys Ther & Rehabil 3(4): 2022. WJYPR.MS.ID.000567.

-

Total knee arthroplasty, Physical therapists, Knee arthroplasty, Osteoarthritis, Hypercholesterolemia, Low-level exercise, Standing heel raises, Knee surgery, Functional deficits, Self-directed exercise, High-intensity strengthening, Daily activities, Eccentric movement, Patient’s treatment.

-

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.