Case Report

Case Report

Secondary Repair of Upper Lid Laceration with Canalicular Laceration, Right A case report

Alexander Gerard Niño L Gungab*, Reynaldo M Javate and Ann Carmeline S Beronilla

Department of Ophthalmology, University of Santo Tomas Hospital Eye Institute,University of Santo Tomas, España, Manila, Philippines

Alexander Gerard Niño L Gungab, Department of Ophthalmology, University of Santo Tomas Hospital Eye Institute, University of Santo Tomas, España, Manila, Philippines.

Received Date: July 20, 2021; Published Date: September 17, 2021

Abstract

Objective: To demonstrate the ease, efficacy and safety of using a monocanalicular stent in repair of a transected canaliculus.

Methods: A case report of an 11-year old male who had an upper lid laceration with canalicular laceration. A Masterka monocanalicular stent was used for repair of the canaliculus.

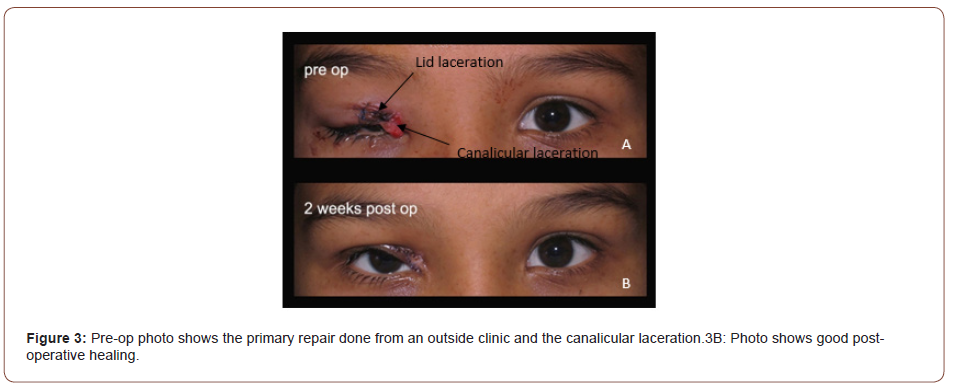

Results:This is a case of an 11-year old male who sustained trauma to the right eye after accidentally hitting a metal clothes hanger while playing at a store which resulted to an upper lid laceration with canalicular laceration. Primary repair was done in a local clinic and was then seen at our institution 5 days post injury. A secondary repair was done using the “one stitch technique” by doing a single pericanalicular horizontal mattress suture which was described by Dr. Kersten and gives an anatomical success rate of 100% (Alam, 2017). A Masterka monocanalicular stent was used to bridge the transected canaliculus. The Masterka silicone tube with punctal fixation, pre-mounted on an introducer to facilitate insertion is placed within the lumens of the canaliculi to bridge the lacerated areas. Monocanalicular stents minimize the risk of injury to the intact canaliculus, compared to bicanalicular silicone stent. The Masterka needs no nasal recovery thus, making it a less traumatic procedure.

Conclusion: Intubation of lacerated canaliculi with a Masterka monocanalicular stent for canalicular repair was safe, effective and simple with minimal complications.

Introduction

The lacrimal canaliculi are widely known to be vulnerable to trauma. This is due to the lack of tarsal support in the medial portion of the eyelids. Canalicular laceration can either come from direct or indirect trauma whether penetrating or non-penetrating injuries. It is also frequently accompanied with other globe or periocular injuries such as eyelid lacerations. [1]. According to a study by Murchinson et al, Canalicular lacerations accompany eyelid lacerations 16% of the time. Children and young adults are commonly affected primarily by their activities. Unrepaired canalicular lacerations may lead to various complications such as inflammation, scarring, canalicular obstruction which would then result to epiphora [1].

There are multiple approaches in repairing a transected canaliculus. One can do repair of the lid laceration without stent intubation, other surgeons prefer intubation of the canaliculus using a monocanalicular or bicanaliclar stent [1]. There is no strict guideline on what surgical technique is used to repair canalicular lacerations but majority agree that it is necessary to use a lacrimal stent in the reconstruction [1]. In terms of canalicular injury repair, the following principles involve: 1. The torn medial end of the canaliculus must be identified, 2. Use high magnification in suturing the cut ends and in intubating the canaliculus in order to prevent fibrosis that would lead to stenosis and thus maintaining the patency of the lumen [2]. The goal of surgical repair is proper surgical approximation of the laceration with restoration of anatomical function.

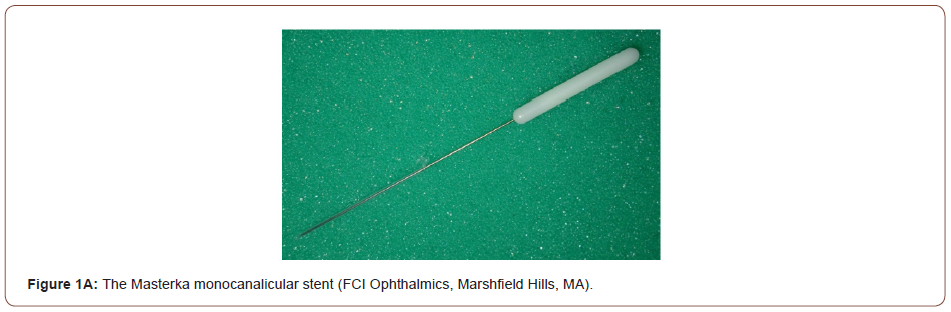

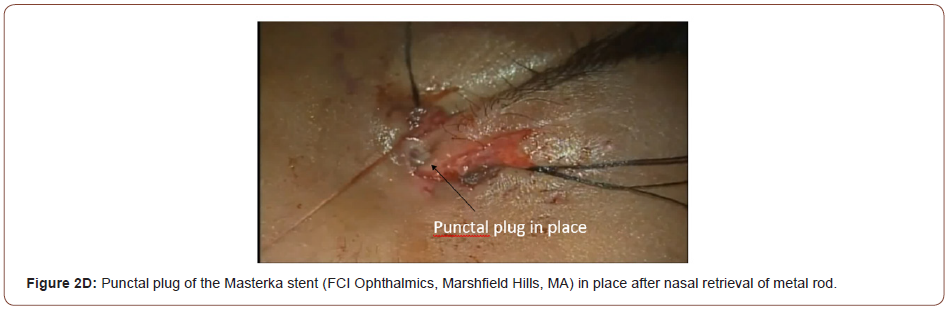

Most conventional method is doing bicanalicular intubation which also involves manipulation of the uninvolved canaliculus. However, there is a need for nasal cavity retrieval of the tube. Thorough experience is required to prevent injury to the nasal mucosa. On the contrary, Monoka and Mini-Monoka (FCI Ophthalmics, Marshfield Hills, MA) monocanalicular tubes, have been reported to be safe and efficacious [1]. One of the later stents called the Masterka monocanalicular stent is a new silicon stent that is primarily used for congenital nasolacrimal duct obstruction cases. This stent is composed of 2 parts: 1st part is fixed at the proximal end of the punctum by means of a punctal plug. 2nd part is a metal probe within the lumen of the stent that serves as a guide that help facilitate the stent insertion. After the intubation, the metal probe is withdrawn from the punctum and the silicone stent is placed in the canaliculus [1]. The Masterka monocanalicular stent can also be safely used for trauma cases.

Methods:

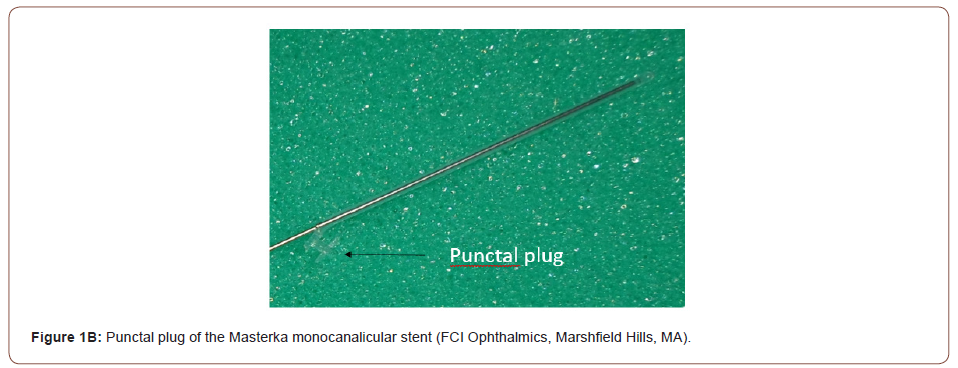

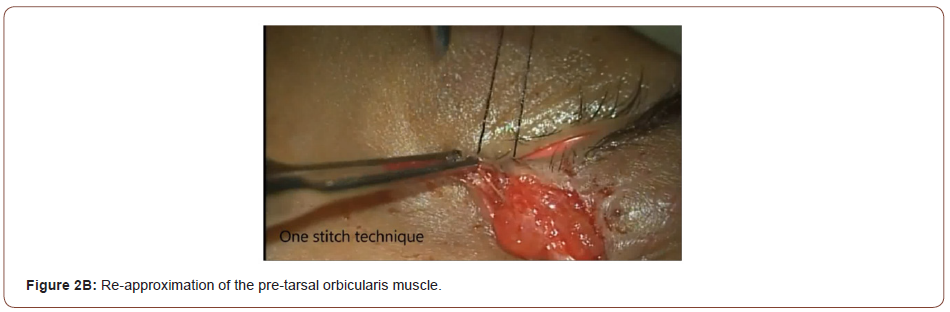

This is a case of an 11-year-old male who sustained an upper lid and canalicular laceration while playing at a local department store. Primary repair was initially done at a local clinic but was advised to be seen by an Oculoplastic specialist. The patient was brought to our institution 5 days post injury and was subsequently scheduled for a secondary repair. Since this was a case of secondary repair, we analyzed how to re-approximate the cut edges of the eyelid and transected canaliculus. Probing of the transected canaliculus was done in order to identify the extent of the cut segments. Reapproximation of the overlying orbicularis muscle was done by using the “One-stitch technique” as described by Dr. Kersten using a 7-0 vicryl suture. Repair of canalicular laceration is simplified by eliminating direct microsurgical anastomosis of the cut mucosa. This in turn would improve success rate, because multiple fine sutures placed through the canalicular epithelium can potentially damage this delicate tissue [1].

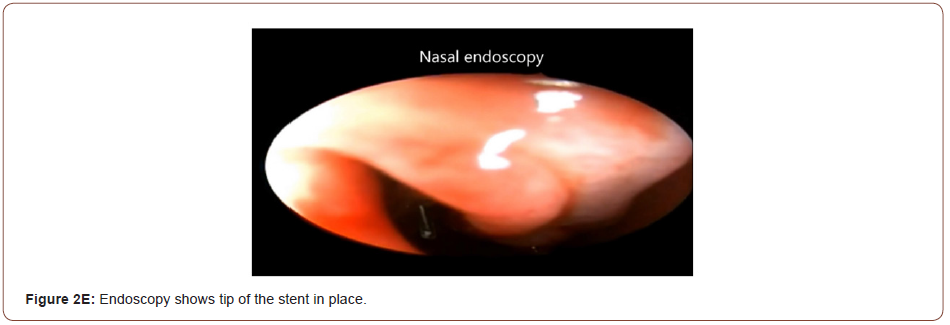

Identifying and locating the distal cut end of the canaliculus is the most challenging part of the repair was especially since this is a case of secondary repair. Topical phenylephrine was applied to the area of injury and this will give vasoconstriction to the vascular and muscular structures surrounding the canaliculus. The proximal end of the transected canaliculus will appear with rolled white edges and a shiny epithelial lining. After identifying both the proximal and distal ends, the Masterka monocanalicular stent was inserted. After successful intubation, the metal probe was withdrawn from the upper punctum. Orbicularis muscle and skin were both closed using absorbable sutures. Nasal endoscopy was done in order to check that the tip of the stent is in place inside the nasal cavity (Figure 1A, 1B, 2A,2B, 2C,2D, 2E).

Results

There were no intraoperative complications encountered during the surgery. The patient was closely monitored on follow ups. No complications were noted such as tube loss, canalicular migration, granuloma tissue formation and chronic irritation all throughout the consultations. The patient did not have any complaints of tearing on the affected eye either (Figure 3-5).

Discussion

Lacrimal canaliculi lacerations usually often accompany eyelid lacerations. Herzum et al. reported that 16% of lacrimal drainage system involvement in 180 patients with eyelid injuries. Naik et al. reported a 36% rate of lacrimal drainge system involvement in 66 patients with eyelid injuries [3]. Canalicular lacerations are not considered an ophthalmic emergency, however, if not managed properly, it can lead to lifelong epiphora. The laceration is preferably repaired within 72 hours of the injury before scarring and epithelization of the cut edges set in. Once inflammatory edema of the pericanalicular tissue set in, identifying the distal cut edges and repair becomes burdensome [2]. The standard of care of canalicular lacerations mandates placing a stent in order to maintain proper alignment of the anastomosis and to prevent stricture after canalicular repair. An indwelling canalicular stent serves to align the cut ends and maintain the lumen during the healing phase [2]. The aim is to achieve an anastomosis within the lacerated canaliculus, and intubation of the canalicular system until re-epithelization of the canalicula has ensued. Re-anastomosis of the canalicular epithelium whether by direct microsurgical or indirect anastomosis is recommended for the satisfactory repair of canalicular lacerations [3].

Traditionally, the standard approach to canalicular repair has been bicanalicular stenting. It has been established that doing bicanalicular intubation yields high success rates of repair. When doing bicanalicular intubation for monocanalicular laceration, it is critical that the utmost care must be taken to avoid iatrogenic injury to the normal, intact canaliculus or damaging further the lacerated one [4]. Bicanalicular stenting approach commonly entails nasal fixation. However, this creates the difficulty of nasal retrieval of the stent beneath the inferior meatus thus the chance for trauma to the nasal mucosa, or worse, creating a slit canaliculus coming from excessive tension brought about by tight nasal fixation [4]. Bicanalicular stents need nasal packing, endoscopic guidance, and intranasal manipulation, all of which may require intravenous sedation or general anesthesia. These stents may produce potential complications, such as false passages, ‘‘cheese wiring’’ or punctal erosion, granuloma formation, anterior loop dislocation, corneal abrasion and infection [2]. These tubes require a “pulled mechanism” and advertently cause bleeding. In contrast, the Masterka stent has a “pushed mechanism” when being placed inside the canaliculus [1].

Two potential complications of Masterka tube might be inadvertent lacrimal system injury and creation of a false passage upon insertion by the metal rod. In order to prevent these, careful and meticulous identification of the distal segment of the lacerated canaliculus must be done and push the stent very gently. Minimal resistance is appreciated once it is inserted in the “true” passage [1]. Monocanalicular stents offers the ease of removal in out-patient setting by holding the phalange at the punctum with forceps under topical anesthesia even in children [2].

Conclusion

The Masterka tube is a safe and effective stent that can be used

in repairing canalicular lacerations. The metal guide serves as an

aid to facilitate tube insertion. The following advantages are:

1. Ease of insertion,

2. No need for nasal cavity retrieval,

3. A self-retaining punctal plug,

4. Shortens duration of the operation,

5. Less traumatizing and minimizes the risk of further

canalicular injury.

[1-10]. However, there are no studies yet to compare the

different success rates of the various monocanalicular stents.

Further investigation is suggested.

Privacy and Confidentiality

All patient data will be anonymized to maintain strict privacy and confidentiality in accordance with the Data Privacy Act. Only the primary investigator and the co-author will have access to the pertinent data. For verification purposes, the IRB will also have access to the data gathered for this study. The data will be stored in the primary investigator’s database which is password-protected and will be stored for the duration of three years and after which all data will be deleted. The identity of the patient will remain confidential even in the event of any publication.

Acknowledgement

We have no financial disclosures in this study.

Conflict of Interest

The primary investigator and the co-author have no financial disclosure nor conflict of interest and has no special funding required for the entirety of the study.

References

- Tavakoli MD, Karimi S, Behdad B, Dizani S, Salour H (2016) Traumatic Canalicular Laceration Repair with a New Monocanalicular Silicone Tube. Journal of Ophthalmic Plastic Reconstructive Surgery 33(1): 27-30.

- Shahid Alam MD, Shrirao Mehta N, Mukherjee B (2017) Anatomical and Functional Outcomes of Canalicular Laceration Repair with self-retaining mini-MONOKA stent Saudi. Journal of Ophthalmology 31: 135-139.

- Selam Yekta Sendul, Halil Huseyin Cagatay, Burcu Dirim, Mehmet Demir, Sönmez Cinar, et al. (2014) Reconstructions of Traumatic Canalicular Lacerations: A 5 Year Experience Open access journal of Science and Technology.

- Clara J Men, Audrey C Ko, Lilangi S Ediriwickrema, Catherine Y Liu, Don O Kikkawa, et al. (2020) Canalicular laceration repair using a self-retaining, bicanalicular, hydrophilic nasolacrimal stent. UCSD Shiley Eye Institiute La Jolla San Diego USA Orbit The International journal on Orbital Disorders Oculoplastic and Lacrimal Surgery 40(3): 239-242.

- Kersten MD, Kulwin MD (1996) “One-stitch'' Canalicular Repair: A Simplified Approach for Repair of Canalicular Laceration Ophthalmology 103(5):785-789.

- Reynaldo M, Javate MD (1998) One stitch Canalicular Repair: Two variations in technique Guest Editor: FIC Operative Techniques in Oculoplastic and Reconstructive Surgery.

- Hwa Lee, Mijung Chi, Minsoo Park, Sehyun Baek (2009) Effectiveness of canalicular laceration repair using monocanalicular intubation with Monoka tubes. Acta ophthalmologica 87(7): 793-796.

- Chowdhury HR, Rose GE, Ezra DG (2014) Long term Outcomes of Monocanalicular Repair of Canalicular Lacerations. Ophthalmology 121(8):1665-1666.

- David A Della Rocca MD, Syed M Ahmad MD, Robert C Della Rocca MD (2007) Direct Repair of Canalicular Lacerations 23(3): 149-155.

- Anastas CN, Potts MJ, Raiter J (2001) Mini Monoka silicone monocanalicular lacrimal stents: Subjective and objective outcomes. MBBS FRACO Cambridge Eye Clinic West Leederville and Bristol Eye Hospital 20(3): 189-200.

-

Alexander Gerard Niño L Gungab, Reynaldo M Javate, Ann Carmeline S Beronilla. Secondary Repair of Upper Lid Laceration with Canalicular Laceration, Right A case report. W J Opthalmol & Vision Res. 3(5): 2021. WJOVR.MS.ID.000573. DOI: 10.33552/WJOVR.2021.03.000573.

-

Canalicular Laceration, Inflammation, Scarring, Oculoplastic Specialist, Tube Loss, Canalicular Migration, Granuloma Tissue Formation, Chronic Irritation

-

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.