Research Article

Research Article

Risk Factors of Strabismus in Children in a Southern Nigerian Tertiary Hospital

H Nwachukwu1, AA Onua2* and AO Adio2

1Department of Ophthalmology, University of Port Harcourt Teaching Hospital, Nigeria

2Department of Ophthalmology, University of Port Harcourt, Nigeria

AA Onua, Department of ophthalmology, University of Port Harcourt, Nigeria.

Received Date: August 13, 2019; Published Date: August 22, 2019

Abstract

Background: Strabismus is a misalignment of the eyes affecting one or both eyes. The deviation of the eyes could be esodeviation, exodeviation, hyperdeviation or hypodeviation. Its prevalence is low globally and varies in different regions of the world. In our local environment esotropia is the commonest form of presentation. The possible risk factors that predispose a child to developing strabismus is necessary for early mitigation.

Objective: The aim of this study is to determine the possible risk factors of strabismus among children attending the Paediatric Ophthalmology Clinic in the university of Port Harcourt Teaching Hospital ( a tertiary hospital) in the Niger Delta Region, Nigeria.

Method: One hundred and twenty-five (125) consecutive children with manifest strabismus attending the Pediatric Ophthalmology Clinic of the University of Port Harcourt Teaching Hospital from October 2016 to March 20 18 were recruited for the study.

Results: The prevalence of manifest strabismus was 6.6%. Refractive error (hypermetropia and astigmatism) was the most prevalent ocular risk factor seen among these children. Other risk factors were amblyopia, prematurity, low birth weight, family history of strabismus and female sex. Conclusion: Adequate cycloplegic refraction should form a baseline clinical procedure for children presenting with strabismus.

Keywords: Children; Risk factor; Strabismus

Introduction

Normal binocular single vision is the ability of the visual cortex to fuse and integrate the image from each eye into a single perception which develops after birth from early infancy and is completed with fusion and stereopsis by age 8-10years [1]. Strabismus is a misalignment of the eyes such that the visual axes of both eyes are not simultaneously directed at the object of regard [2]. Ocular misalignment is common in newborns because humans are often born with a slight exodeviation thought to represent the anatomic position of the divergent orbit [3]. A study done in university of Liverpool found the prevalence of strabismus to be about 73.1% in one-month old babies, reducing to 49% in two months old and virtually disappearing in normal four-month-old babies [4]. In cases where the patient tends to consistently fixate with one eye and squint with the other, amblyopia is bound to set in especially in young children due to the continuous abnormal visual stimulation from the weaker eye during early visual development with subsequent disruption of neurodevelopment of the visual centers in the brain [5,6].

Strabismus is a relatively common condition worldwide especially among newborns with a prevalence of 1.3% -5.7% in all children with an increased prevalence associated with assisted delivery, low birth weight, prematurity and associated neurodevelopmental disorders [7,8].

In America, a population-based study of strabismus among Native American children showed a prevalence of 3.8% [9]. Asian population reveal a lower prevalence of 0.7-1.9% [10,11]. About 3-4% of Caucasian children have also been reported to be affected with strabismus [12]. The prevalence in Africa is generally low compared to Caucasians and Asians as seen in various studies [13,14]. In Nigeria the prevalence of strabismus is between 0.01- 2.4% in different populations [15-22]. In a retrospective study conducted in the university of Port Harcourt Teaching Hospital the prevalence of strabismus was 0.6% and majority was found between the age group of 0-10 years (75.7%) [16].

Risk factors of strabismus in children include refractive error, positive family history, history of maternal cigarette smoking during pregnancy, low birth weight, prematurity, developmental ocular abnormalities such as craniofacial abnormalities (e.g. Crouzon Syndrome), cataract, retinoblastoma and retinopathy of prematurity [23-31]. Hypermetropia was most commonly found among children with esotropia and myopia among children with exotropia [23,32]. Other risk factors of strabismus include systemic disorders such as meningitis, encephalitis, neonatal jaundice, cerebral palsy, Down’s syndrome and fetal alcohol syndrome [33- 41].

Strabismus affects a child’s psychology and social interaction, and this cannot be neglected. Patients with strabismus are said to have lower levels of psychological well-being, are less accepted by their peers and the society at large [42,43]. This underscores the importance of this study- to identify the risk factors associated with strabismus in our locality and hence improve in the management of our patients.

Materials and Method

The study design is a hospital based descriptive crosssectional study conducted over a period of twenty-four months. The sampling technique used was a consecutive sampling method in which all children with manifest squint attending the Pediatric Ophthalmology Clinic, university of Port Harcourt Teaching Hospital from October 2016 to March 2018 were recruited consecutively into this study. The university of Port Harcourt Teaching hospital serves as a catchment as well as a referral Centre for inhabitants of Rivers State and neighboring Bayelsa, Imo and Abia states.

An interviewer-administered questionnaire was administered in the clinic to the assenting patients whose parent/guardian has given consent. Relevant information on socio-demography such as birth history, age at onset of squint, history of previous trauma, previous eye surgery and family history of squint were obtained from either parent/guardian via interviews. Visual acuity (VA) was tested in preverbal children (0-2yrs) using preferential looking, Central, Steady and Maintained fixation, fixating and following of bright light or bright colored toy. While in verbal children (>2yrs), visual acuity was done with a picture optotype test e.g. Kay’s pictures test; which uses pictures of objects like cars, trains houses, bikes, animals. Snellen acuity chart or illiterate E-chart asking the child to point his/her finger to the direction of the E. Pin-hole testing was done for subjects with VA of 6/12 and worse.

Corneal light reflex (Hirschberg’s test) was carried out for near and target object. The position of the light reflection on each cornea with reference to the pupil was noted. Bruckner test was performed using the direct ophthalmoscope in a dark room to obtain a red reflex simultaneously in both eyes at arm’s length. Cover and uncover test was also done monocularly at both near and distance. It was done to detect presence of manifest squint and to differentiate between phoria and tropia. Alternate prism cover test was done to measure the total deviation which is the degree of deviation. The degree of deviation was assessed with modified Krimsky’s test which is similar to Hirschberg’s test except that the prism was placed in front of the fixating eye with the apex facing the direction of deviation to center the corneal reflection in the deviated eye.

Anterior segment examination was done with a pen torch and slit lamp looking out for the eyelids, size of the globe and extraocular muscles motility, conjunctiva and pupils. A dilated fundoscopy was done for all children using a binocular indirect ophthalmoscope to assess the macula, optic disc, and peripheral retina for any pathology such as retinoblastoma, glaucoma, optic disc coloboma, toxoplasmosis etc. All data generated was entered into a proforma and were analyzed using commercially available statistical data management software- Statistical Package for Social Sciences (IBM-SPSS) version 23.

Consent and Ethical Clearance

Ethical clearance was obtained from the Ethical Committee of University of Port Harcourt Teaching Hospital. Informed written consent and assent were obtained from each patient’s parent before enrolment into the study in accordance with Helsinki Declaration involving human subjects [44].

Results

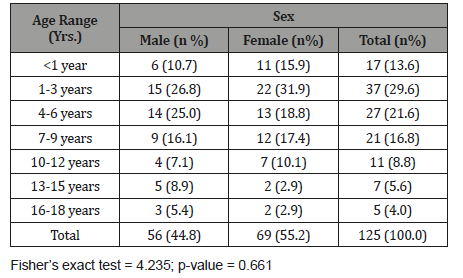

(Table1)

Table 1: Age and sex distribution of study population.

Sixty-nine were females (55.2%) while 56 were males (44.8%). Male to female ratio was 1:1.2. Mean age was 5.53±4.42years. Age range of 1-3years had the highest proportion 37 (29.6%) while those 16-18 years had the least representation 5(4.0%). The differences in the proportion of age categories between the males and females were not statistically significant (p =0.661).

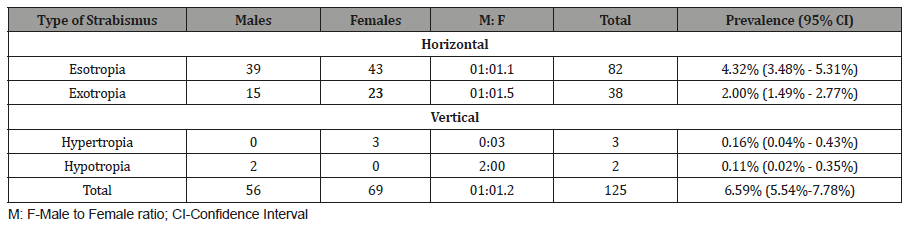

(Table 2)

Esotropia has a prevalence of 4.3%, 38 (2.0%) subjects had exotropia out of which 15 were male and 23 were female while that for vertical deviation was 0.27% (hypertropia 0.16%, hypotropia 0.11%). The overall prevalence for heterotropia was 6.6%.

Table 2: Prevalence and gender distribution of types of strabismus.

Discussion

This was a cross sectional study conducted among 125 children with strabismus attending the pediatric eye clinic of the University of Port Harcourt Teaching Hospital. The aim of the study was to unravel the risk factors associated with strabismus among children in our locality.

The prevalence of strabismus in this study was 6.6% which was similar to the hospital-based study carried out in Tanzania (5.9%) [45] and Australia (7.3%) [46]. It was slightly higher than the global prevalence of 3–5% [47] and those reported in different parts of Nigeria [12-14,17-22]. Most of the studies done in Nigeria were primarily to assess ocular diseases in children, therefore standardized methods of examining strabismus may not have been applied which could have led to cases of missed strabismus [15,16,48]. However, the high prevalence obtained in this study is similar also to the findings of a population-based study in China [49]. In developed countries like China, there are better awareness to ocular health, improved health care facility, maternal nutrition and perinatal child health care; these factors probably account for the low prevalence of strabismus. The relative high prevalence of strabismus in our study, could be attributed to the fact that all children presenting with strabismus were included in this study (not just healthy children) and the prevalence was calculated in relation to the total number of children presenting within the study period. In addition, this study was hospital-based and more yield of patients with strabismus was expected.

In the course of this study different ocular and systemic morbidities were found to be implicating risk factors in manifest strabismus. These risk factors include refractive error, prematurity, family history and female sex. Refractive error was noticed in 64.6%. Hypermetropia was the commonest type seen amongst the subjects; this finding was similar to findings in a clinic- based study by Al- Tamini [32], Zhu [49], Baiyeroju [20], Bodunde [17] and Azonobi, et al. [15]. Hypermetropia was found to be more common in subjects with esotropia in this study, which is similar to studies done in other parts of the world such as United States 47 China 50 and Australia 51. This was followed by astigmatism (22%). The multiethnic pediatric eye disease study/Baltimore pediatric eye disease study observed that astigmatism was implicated in exotropia26 but in this study astigmatism was implicated in esotropia. Also, in this study, 16% of the subjects were myopic and was found to be more prevalent among subjects with esotropia. In contrast to the findings of Zhu, et al. [49], Azonobi, et al. [23] who observed that myopia was predominant among subjects with exotropia. In our study, maternal smoking in pregnancy was not considered a risk factor because smoking among females is rare in our locality.

Amblyopia is a cause of visual impairment in children especially those with strabismus. The prevalence of amblyopia in this study was 16.0%. It is the second most implicating risk factor seen in this study. It is more prevalent among the esotropic subjects. Systemic co-morbidities found among the subjects in this study included cerebral palsy /birth asphyxia, neonatal jaundice, oculocutaneous albinism, low birth weight, meningitis, and sickle cell disease. These are similar to the findings in Tanzania [50]. Cerebral palsy is almost equally found among subjects with esotropia and exotropia. Prematurity/ low birth weight was also seen among subjects with esotropia in this study.

Acknowledgment

None.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors hereby declare that there is no conflict of interest.

References

- Bilson F (2003) Fundamentals of Clinical Ophthalmology series, Strabismus. 1st (edn), BMJ Publishing Group, UK.

- Taylor D, Creigs S Hoyt (2005) Paediatric Ophthalmology and Strabismus. 3rd (edn), Optometrists Association Australia, Australia, pp.1-1170.

- Mohney BG, Greenberg AE, Diehl NN (2007) Age at strabismus diagnosis in an incidence cohort of children. Am J Ophthalmol 144(3): 467-469.

- Horwood A (2003) Neonatal ocular misalignments reflect vergence development but rarely become esotropia. Br J Ophthalmol 87(9): 1146-1150.

- Alex V, Lewin TW (2007) Atlas of Pediatric Ophthalmology and Strabismus Surgery. 1st(edn), Canada.

- (2012) Basic & Clinical Science Course. Pediatric Ophthalmology and Strabismus, American Academy of Ophthalmology, USA, pp. 94120-7424.

- Ferreira R da C, Oelrich F, Bateman B (2002) Genetic aspects of strabismus. Arq Bras Oftalmol 65: 171-175.

- Taylor R (2012) The Royal College of Ophthalmologists Guidelines for the Management of Strabismus in Childhood. London, UK.

- Garvey KA, Dobson V, Messer DH, Miller JM, Harvey EM (2010) Prevalence of strabismus among preschool, kindergarten, and first-grade Tohono O’odham children. Optometry 81(4): 194-199.

- Dandona R, Dandona L, Srinivas M, Sahare P, Narsaiah S, et al. (2002) Refractive error in children in a rural population in India.Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 43(3): 615-622.

- Goh PP, Abqariyah Y, Pokharel GP, Ellwein LB (2005) Refractive error and visual impairment in school-age children in Gombak District, Malaysia. Ophthalmology 112(4): 678-685.

- Mohney BG (2007) Common forms of childhood strabismus in an incidence cohort. Am J Ophthalmol 144(3): 465-467.

- Azonobi I, Olatunji F, Adido J, Osayande O (2008) Vision of Strabismic Children in Ilorin, Nigeria. Niger J Ophthalmol 16: 12-15.

- Wedner SH, Ross DA, Balira R, Kaji L, Foster A (2000) Prevalence of eye diseases in primary school children in a rural area of Tanzania. Br J Ophthalmol 84(11): 1291-1297.

- Azonobi IR, Olatunji FO, Addo J (2009) Prevalence and pattern of strabismus in Ilorin. West Afr J Med 28(4): 253-256.

- Awoyesuku E, Fiebai B, Onua A (2016) Pattern of strabismus in a tertiary hospital in Nigeria: a six-year review. Port Harcourt Medical Journal 10(1): 14.

- Bodunde, OT, Onabolu, OO, F akolujo VO (2014) Pattern of squint presentations in children in a tertiary institution in Western Nigeria. IOSR J Den Med Sci 13(5): 29-31.

- Ajaiyeoba AI, Isawumi MA, Adeoye AO, Oluleye TS (2006) Prevalence and causes of eye diseases amongst students in south-western Nigeria. Annals of African medicine 5(4): 197-203.

- Abah ER, Oladigbolu KK, Samaila E, Gani Ikilama A (2011) Ocular disorders in children in Zaria children’s school. Niger J Clin Pr 14(4): 473-476.

- Baiyeroju Agbeja AM OJ (1998) Strabismus in children in Ibadan. Niger J Ophthamol 6: 31-33.

- Akpe BA, Dawodu OA AE (2014) Prevalence and pattern of strabismus in primary school pupils in Benin City, Nigeria. Nigerian Journal of Ophthalmology 22(1): 38-43.

- Osahon AI, Dawodu OA (2002) Pattern of eye disease in children in Benin City, Nigeria. Trop Doc 32(3): 158-159.

- Azonobi R, Olatunji F, Adido J (2009) Refractive Error Among Strabismic Children in Ilorin. Afr J Opthalmol 21(1-4)

- Maconachie GDE, Gottlob I, McLean RJ (2013) Risk factors and genetics in common comitant strabismus: a systematic review of the literature. JAMA Ophthal 131(9): 1179-86.

- Parikh V, Shugart YY, Doheny KF, Zhang J, Li L, et al. (2003) A strabismus susceptibility locus on chromosome 7p. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA,100(21): 12283-12288.

- Cotter SA, Varma R, Tarczy-Hornoch K, McKean-Cowdin R, Lin J, et al. (2011) Risk factors associated with childhood strabismus: the multi-ethnic pediatric eye disease and Baltimore pediatric eye disease studies. Ophthalmology 118(11): 2251-2261.

- Torp Pedersen T, Boyd HA, Poulsen G, Haargaard B, Wohlfahrt J, et al (2010) Perinatal risk factors for strabismus. Int J Epidemiol 39(5): 1229-139.

- Weiss AH, Phillips J, Kelly JP (2014) Crouzon syndrome: relationship of rectus muscle pulley location to pattern strabismus. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 55(1): 310-317.

- Guha S, Ravishankar K, Surendran TS (2008) Performing combined strabismus and cataract surgery: an effective approach in selected cases. Strabismus 16(1): 5-9.

- Balmer A, Munier F (2007) Differential diagnosis of leukocoria and strabismus, first presenting signs of retinoblastoma. Clin Ophthalmol 1(4): 431-439.

- Dogra MR, Narang S, Biswas C, Gupta A, Narang A (2001) Threshold retinopathy of prematurity: ocular changes and sequelae following cryotherapy. Indian J Ophthalmol 49(2): 97-101.

- Al Tamimi ER, Shakeel A, Yassin SA, Ali SI, Khan UA (2015) A clinic-based study of refractive errors, strabismus, and amblyopia in pediatric age-group. J Family Community Med 22(3): 158-162.

- Lamba PA, Bhalla JS, Mullick DN (1986) Ocular manifestations of tubercular meningitis: a clinico-biochemical study. J Pediatr Ophthalmol Strabismus 23(3): 123-125.

- Jain S, Patel B, Bhatt GC (2014) Enteroviral encephalitis in children: clinical features, pathophysiology, and treatment advances. Pathog Glob Health 108(5): 216-222.

- Rose J, Vassar R (2015) Movement disorders due to bilirubin toxicity. Semin Fetal Neonatal Med 20(1): 20-25.

- Hunter DG, Ellis FJ (1999) Prevalence of systemic and ocular disease in infantile exotropia: comparison with infantile esotropia. Ophthalmology 106(10): 1951-1956.

- Lagunju IA, Oluleye TS (2007) Ocular abnormalities in children with cerebral palsy. Afri J Med Med Sci 36(1): 71-75.

- Kim U, Hwang JM (2009) Refractive errors and strabismus in Asian patients with Down syndrome. Eye 23(7): 1560-1564.

- Abdelrahman A, Conn R (2009) Eye abnormalities in fetal alcohol syndrome. Ulster Med J 78(3): 164-165.

- Strömland K, Hellström A (1996) Fetal alcohol syndrome--an ophthalmological and socioeducational prospective study. Pediatrics 97: 845-850.

- Torp Pedersen T, Boyd HA, Poulsen G, Haargaard B, Wohlfahrt J, et al. (2010) Perinatal risk factors for strabismus. Int J Epidemiol 39(5): 1229-1239.

- Tukkers van Aalst FS, Rensen CS, De Graaf ME, van Nieuwenhuizen O, Wittebol Post D (2007) Assessment of psychomotor development before and after strabismus surgery for infantile esotropia. J Paed Ophth Strab 44(6): 350-355.

- (2013) World Medical Association. World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki. JAMA 2191: 2194

- Williams C, Northstone K, Howard M, Harvey I, Harrad RA, et al. (2008) Prevalence and risk factors for common vision problems in children: data from the ALSPAC study. Br J Ophthalmol 92(7): 959-964.

- Ip JM, Robaei D, Rochtchina E, Mitchell P (2006) Prevalence of Eye Disorders in Young Children with Eyestrain Complaints. Am J Ophthalmol 142(3): 495-497.

- Adelstein AM, Scully J (1967) Epidemiological aspects of squint. Br Med J 3(5561): 334-338.

- Sharbini SH (2015) Prevalence of Strabismus &Amp; Associated Risk Factors: The Sydney Childhood Eye studies. The University of Sydney, Australia, pp. 1-291.

- Zhu H, Yu JJ, Yu RB, Ding H, Bai J, et al. (2015) Association between Childhood Strabismus and Refractive Error in Chinese Preschool Children. PLoS One 10(6): e0130914.

- Njambi L (2017) Prevalence and pattern of manifest strabismus in paediatric patients at CCBRT, Dar es Salaam, Tanzania. London, UK. Tanzania J Ophthalmol East Cent South Africa 13: 23-30.

- Schaal LF, Schellini SA, Pesci LT, Galindo A, Padovani CR, et al. (2018) The Prevalence of Strabismus and Associated Risk Factors in a Southeastern Region of Brazil. Semin Ophthalmol 33(3): 357-360.

-

H Nwachukwu, AA Onua, AO Adio. Risk Factors of Strabismus in Children in a Southern Nigerian Tertiary Hospital. W J Opthalmol & Vision Res. 2(4): 2019. WJOVR.MS.ID.000541.

-

Strabismus, Esodeviation, Exodeviation, Hyper-deviation, Hypo-deviation, Environment, Esotropia, Children, Risk factor, Ocular misalignment, Visual stimulation.

-

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.