Research Article

Research Article

Pattern of Inheritance and Career Choices of Secondary School Students Screened for Color Vision Disorders

Ibifubara N Aprioku1 and Elizabeth A Awoyesuku2*

1Department of Ophthalmology, Rivers State University Teaching Hospital, Nigeria

2Department of Ophthalmology, University of Port Harcourt Teaching Hospital, Nigeria

Elizabeth A Awoyesuku, Department of Ophthalmology, University of Port Harcourt Teaching Hospital, Nigeria.

Received Date: August 24, 2019; Published Date: September 03, 2019

Abstract

To ascertain the pattern of inheritance and career choices of secondary school students screened for color vision disorder.

Methodology: The study is a community- based descriptive cross-sectional study involving public secondary school students from randomly selected schools. The participants had a comprehensive ophthalmological eye examination after which a structured questionnaire was administered to ascertain their future career choices. All data generated were entered into a personal computer and then analyzed with the help of a statistician using commercially available Statistical Package for Social Sciences Package version 21 (SPSS-21). Mean and standard deviations were determined for age.

Results: One thousand secondary school students showing a 100% response rate were interviewed. 73.9% of those with CVD reported a positive family history of CVD (p-value 0.0220). Majority of the color-blind students indicated preference for the medical and engineering occupations.

Conclusion: Most of the color-blind students indicated a preference for careers where color vision will be essential. Measures should be put in place to set up school eye screening programs to educate and ensure that students are screened for CVD at least once during secondary education to ensure proper vocational counseling and choice.

Keywords: Career choices; Color vision disorders; Secondary school

Introduction

Color vision disorders (CVD) also known as color blindness or color vision defects are one of the commonest genetic and inherited disorders observed in the human population [1,2,3,4]. Color vision results from stimulation of the cones in the retina in different combinations. [5] Color vision disorders can either be congenital or acquired. [6] With the inheritance patterns, being sex or X linked recessive and is said to be commoner in males than females.

In a study by Al Aqtum et al. on-University students in Jordan, the allelic frequencies of the color vision gene was found to 0.087 in males and 0.003 in females. [7] The congenital type is mainly of the red green pattern, symmetrical and bilateral and ranges in severity from mild to severe with a prevalence of 8% in males and 0.5% in females. On the other hand, the acquired type usually has no inheritance pattern, most commonly of the yellow blue variety, unilateral and asymmetrical in the two eyes. [8-9] Color vision is important in many activities of daily living. There are four major tasks under which the importance of color falls and they include: [10].

1. Connotative color tasks: Here colors are assigned to or have acquired specific meanings for instance the colors of signal lights, warning lights or color codes on electrical equipment, in chemical tests or colors of fruits signifying degree of ripeness, or body color in identifying progression of illness.

2. Denotative color tasks: here color is used to mark out objects such as the identification of one’s car, organizing complex visual display units, facilitating a visual search or to attract attention.

3. Comparative color tasks: color here is used in discrimination of objects and to discern small color differences.

4. Aesthetic color tasks: color is used to create an emotional response or convey a mood. This is of importance in graphic and decorative arts, clothing design, interior décor and building.

Mild cases of color vision disorder are compatible with everyday activity and most vocations, [11] moderate and severe ones are however associated with difficulty in day to day activity [11,12]. Barry Cole, [10] in his review article on the handicap of color vision stated that almost all those with color vision disorders reported having problems with everyday activities such as reading color printed material and computer displays.

The importance of good color vision was further emphasized by Birch et al. [13] in Northern Ireland. They reported that more than 65% of serving police officers considered good color vision important for effective policing with only 2% considering it unimportant. In a study by Cole et al. [14] it was also reported that color blind individuals had a slower response time and higher error rates than normal individuals when using video terminals or computer display units. Protanopes were said to be particularly disadvantaged in responding to a “fail” message. Campbell et al. [15] in a study of doctors and their assessment of clinical photographs discovered that, doctors with CVD differed from controls in respect of their ability to detect, and in their confidence in the assessment of abnormalities presented in clinical photographs.

The choice of a career is most times made during secondary education; hence the rationale for testing for color vision at the secondary school level before a definitive career choice is made.

Materials and Methods

The study is a community- based descriptive cross-sectional study involving public secondary school students from randomly selected schools in Rivers State. Ethical clearance for the study was obtained from the Ethical committee of the hospital. The participants who met the inclusion criteria were selected using a multistage random sampling technique. The participants had a comprehensive ophthalmological eye examination and Ishihara color vision testing was carried out in a room with sufficient indirect daylight illumination or outdoors using the 24 plate 2009 edition. Subjects who were able to identify 13 or more plates were adjudged to have normal color vision while those that identified only nine plates or less were judged to have failed the screening test. Such subjects were then shown diagnostic plates 16 and 17 to determine if colour vision defect was protan or deutan. The prevalence of CVD was determined by the number of students who failed the Ishihara test.

These same subjects who failed the Ishihara test were then administered the Farnsworth Munsell D15 test to further classify and grade the pattern and severity of color blindness. At the end of the tests a structured questionnaire was administered to ascertain their future career choices.

All data generated were entered into a personal computer and then analyzed with the help of a statistician using commercially available Statistical Package for Social Sciences Package version 21 (SPSS-21). Mean and standard deviations were determined for age.

Results and Discussion

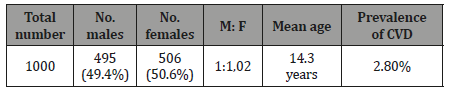

One thousand secondary school students showing a 100% response rate were interviewed. There were 495 males (49.4%) and 506 (50.6%) females with a male female ratio of 1:1.02. Mean age of students was 14.3 years. The prevalence of color vision disorders was 2.8 % (p-value 0.000).

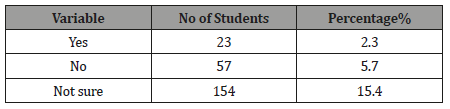

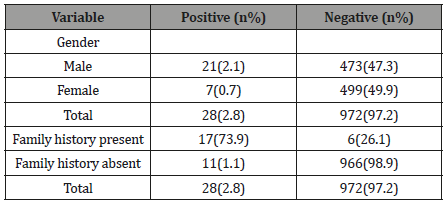

73.9% of those with CVD reported a positive family history of CVD (p-value 0.0220) (Table 1).

Table 1: Demographics of study population.

Three-quarters of students with positive family history of color vision disorder were color blind 17 (73.9%) and this proportion was also statistically significant (X2 = 5.261, df=1 p-value = 0.022). Over 70% (n=17; 73.9%) of the students with CVD in this study had a positive family history of color vision disorder and this association was statistically significant (p-value 0.022).

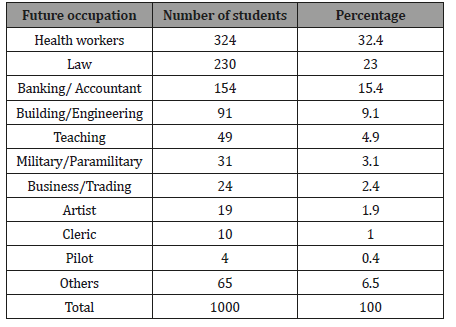

Table 2 showed the desired future occupation of the study subjects. Majority of the students desired to be health workers (n=324; 32.4%) (Table 2).

Table 2: Future occupation desired by the Study Subjects.

Others include mass communication, sportsmen, and language analysts

Health workers include doctors, nurses, and medical laboratory scientists (Table 3 & 4).

Table 3: Family history of Color Vision Disorder.

Table 4: Color vision disorder in students with positive family history.

Table 4 Three-quarters of students with positive family history of color vision disorder were color blind 17 (73.9%) and this proportion was also statistically significant (X2 = 5.261, df=1 p-value = 0.022)

Over 70% (n=17; 73.9%) of the students with CVD in this study had a positive family history of color vision disorder and this association was statistically significant (p-value 0.022). The CVD was of the congenital variety. A similar trend was noticed by Dahlan et al. [16] where he reported a higher prevalence of CVD (35.5%) amongst those with a positive family history in comparison to those without a positive history (20.5%). The higher values noted in this study may not have been unrelated to the poor understanding of the leading question by the respondents. This differed from a study carried out by Dargahi et al. [17] who noted in his study that all the color-blind individuals had a positive family history of the defect, although the correlation was not statistically significant.

More than half of the respondents with CVD desired to become doctors, engineers and military personnel. These findings were similar to that carried out by Dahlan and colleagues, [16] where a higher percentage of those with CVD either wanted to study in medical or engineering colleges. Patients with CVD do badly at sciences in secondary schools as a result of most of the color associated learning materials like graphs, maps etc, in sports they may also be unable to differentiate opponents because of poor color discrimination [18].

Certain occupations are not suitable for people with color vision deficiency and people with CVD may even be barred from working in some environments [19], Occupations such as medicine and paramedical specialties, engineering , air pilot require good color vision to function well [20,21,22,23]. Although CVD does not strictly qualify as a disability there is increased advocacy for early screening and environmental adjustments to allow those with CVD function optimally without posing a danger to themselves or others.

There is the need to incorporate color vision screening into the school curriculum as this may result in timely intervention in career choices in certain individuals [24, 25].

Conclusion

CVD people face a lot of difficulties in everyday life. Over 70% of color-blind students in this study had a positive family history while more than 50% of students indicated they wanted to be health workers, lawyers and engineers. Lifelong decisions / vocational choices are made in secondary school. Screening for CVD should be done early in life so affected individuals can take appropriate measures and guard against lifelong difficulties,

FOSMN is a rare and slowly progressive motor neuron disorders.

Acknowledgment

We thank Dr. CN Pedro Egbe for proof reading the manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

No conflict of interest.

References

- (2014) Living with Color Blindness, what is Color Blindness, what causes colour blindness.

- Al Aqtum MT, Al Qawasmeh MH (2001) Prevalence of Colour Blindness in Young Jordanians. Ophthalmologica 215(1): 39-42.

- Simunovic MP (2010) Colour vision deficiency. Eye (Lond) 24(5): 747-755.

- Godar S, Kaini K, Khattri J (2014) Profile of Color Vision Defects in a Tertiary Care Hospital in Western Nepal. Nepal J Med Sci 3(1): 6-9.

- Tidy C (2011) Colour vision and its disorders. pp. 1-3.

- Natu M (1987) Colour blindness-A rural prevalence survey. Indian J Ophthalmol 35(2): 71-73.

- Al Aqtum MT, Al Qawasmeh MH (2001) Prevalence of Colour Blindness in Young Jordanians. Ophthalmologica 215(1): 39-42.

- Wong TY (2011) colour vision. In: Ophthalmology examinations review, singapore: world scientific publishing, Singapore, pp. 487-489.

- Crognale M, Duncan C (2013) The locus of color sensation: Cortical color loss and the chromatic visual evoked potential. J Vis 13(10): 1-11.

- Cole BL (2004) The handicap of abnormal colour vision. Clin Exp Optom 87(4-5): 258-275.

- Tabansi PN, Anochie IC, Nkanginieme KEO, Pedro-Egbe CN (2008) Screening for congenital color vision deficiency in primary children in Port Harcourt City; teachers’ knowledge and performance. Niger J Med 17(4): 428-432.

- Delpero W, O’Neill H (2005) Aviation-relevent epidemiology of color vision deficiency. Aviat space, Environ Med 76(2): 127-133.

- Birch J, Chisholm CM (2008) Occupational colour vision requirements for police officers. Ophthalmic Physiol Opt 28(6): 524-531.

- Cole BL, Macdonald WA (1988) Defective colour vision can impede information acquisition from redundantly colour-coded video displays. Ophthalmic Physiol Opt 8(2): 198-210.

- Campbell JL, Spalding AJ, Mir FA, Birch J (1999) Doctors and the assessment of clinical photographs--does colour blindness matter? Br J Gen Pract 49(443): 459-461.

- Dahlan H, Mostafa O (2013) Screening for Color Vision Defects among Male Saudi Secondary School Children in Jizan City, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. Med JCairo Univ 81: 513-517.

- Dargahi H, Einollahi N, Dashti N (2010) Color blindness defect and medical laboratory technologists: unnoticed problems and the care for screening. Acta Med Iran 48(3): 172-177.

- Xin Bei V. Chan,Shi Min S Goh, Ngiap Chuah Tai (2014) Subjects with colour vision deficiency in the community: what do primary care physicians need to know?Asia Pacific Medicine 13:10

- (2019) Color Blindness and Occupations available.

- Spalding JA (1999) Medical students and congenital colour vision deficiency: Unnoticed problems and the case for screening. Occup Med (Lond) 49(4): 247-252.

- Campbell JL, Spalding JA, Mir FA (2004) The description of physical signs of illness in photographs by physicians with abnormal colour vision. Clin Exp Optom 87(4-5): 334-338.

- Cumberland P, Rahi JS, Peckham CS (2005) Impact of congenital colour vision defects on occupation. Arch Dis Child 90(9): 906-908.

- Subho Chakrabarti (2018) Psychosocial aspects of colour vision deficiency: Implications for a career in medicine. Natl Med J India 31(2): 86-96.

- Ugalahi MO, Fasina O, Ogun OA (2016) Impact of congenitak color vision defect on color-related tasks among secondary school students in Ibadan, Southwest Nigeria. Nigerian Journal of Ophthalmology 24(1): 20-24.

- Sushil K, Mandira M, Binod R, Arun D, Rani G (2017) Prevalence of Congenital Colour Vision Deficiency (CVD)in School Children of Bhaktapur. International Journal of Medical Science and Clinical Inventions, Nepal 4(8): 3137-3139.

-

Elizabeth A Awoyesuku, Ibifubara N Aprioku. Pattern of Inheritance and Career Choices of Secondary School Students Screened for Color Vision Disorders. W J Opthalmol & Vision Res. 2(4): 2019. WJOVR.MS.ID.000544.

-

Color Vision Disorders, Pattern of Inheritance, career choices, color vision disorders, secondary school, human population, unilateral, asymmetrical.

-

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.