Research Article

Research Article

Visual Outcomes and Subjective Satisfaction After Intracorneal Ring Segment Implantation in Patients with Keratoconus

Seyed Mohammad Ghoreishi1†, MD, Sana Niazi2,3†, MD, MPH, PhD, Maedeh Mazloomi2,3, MD and Farideh Doroodgar2,3*, MD, MPH, FICO

1Ophthalmology Department, Isfahan University of Medical Sciences, Isfahan, Iran

2Translational Ophthalmology Research Center, Tehran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran

3Negah Aref Ophthalmic Research Center, Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran

Farideh Doroodgar, MD, MPH, FICO Farabi Eye Hospital, Qazvin Square, Tehran 1336616351, Iran

Received Date:May 01, 2025; Published Date:June 02, 2025

Abstract

Background and Objectives: The treatment of keratoconus (KCN) remains challenging, and research continues to explore alternative therapies

with minimal risk. Intra-corneal ring segment (ICRS) implantation has been proposed as a rapid intervention with low complication rates. This

cohort study aims to report the 5-year outcomes of Corneal ring implantation according to an elevation map in patients with KCN.

Materials and Methods: Adult patients diagnosed with KCN based on physical examination, presenting with decreased visual acuity and no

systemic or ocular complications, were selected for Corneal ring implantation. Indications for implantation included intolerance to contact lenses,

inadequate response to spectacles or phakic intraocular lenses, and inability to tolerate the complications of corneal transplantation. Femtosecond

laser was used for channel dissection. Demographic data, including age, sex, medical history, chief complaints, and intra- and postoperative

complications, were recorded. Additionally, patients’ quality of life (QOL) was assessed using the National Eye Institute Refractive Error Quality of Life (NEI-RQL) questionnaire.

Results: No complications were reported in any of the patients. Visual acuity improved in all cases, with most achieving a best corrected visual acuity (BCVA) of 10/10 and only a few required corrections. Moreover, patients’ QOL showed significant improvement postoperatively.

Conclusion: Corneal ring implantation in adult patients with KCN not only led to improved visual outcomes but also resulted in favorable

subjective outcomes, as indicated by the significant enhancement in patients’ quality of life. These findings support the corneal ring implantation

according to elevation as a viable treatment option for KCN.

Keywords: Keratoconus; Intra-corneal Ring Implantation; Quality of Life; Visual Acuity; Intra-corneal Ring Segment; Refractive Surgery

Abbreviations:BCVA: Best-Corrected Visual Acuity; CDVA: Corrected Distance Visual Acuity; cpd: Cycles Per Degree; D: Diopters; FDA: Food and Drug Administration; FSL: Femtosecond Laser; ICRS: Intracorneal Ring Segments; KCN: Keratoconus; logMAR: Logarithm of the Minimum Angle of Resolution; NEI-RQL: National Eye Institute Refractive Error Quality of Life; NEI-VFQ: National Eye Institute Visual Function Questionnaire; QOL:Quality of Life; RMS: Root Mean Square; UCVA: Uncorrected Visual Acuity.

Introduction

Overview of Keratoconus (KCN) and Intracorneal Ring Segments (ICRS) Keratoconus (KCN) is a non-inflammatory corneal ectatic disorder characterized by progressive, bilateral, and typically asymmetric thinning and protrusion of the corneal stroma. These structural changes result in irregular astigmatism, higher-order aberrations, and reduced visual acuity due to distorted corneal shape and light refraction [1]. While keratoplasty is frequently performed in severe KCN cases, it represents just one of several treatment options [2]. Other management strategies include contact lens wear, thermokeratoplasty, corneal collagen crosslinking, and intracorneal ring segment (ICRS) implantation (synthetic and allogenic), each designed to the stage and severity of the disease [3].

History and development of ICRS

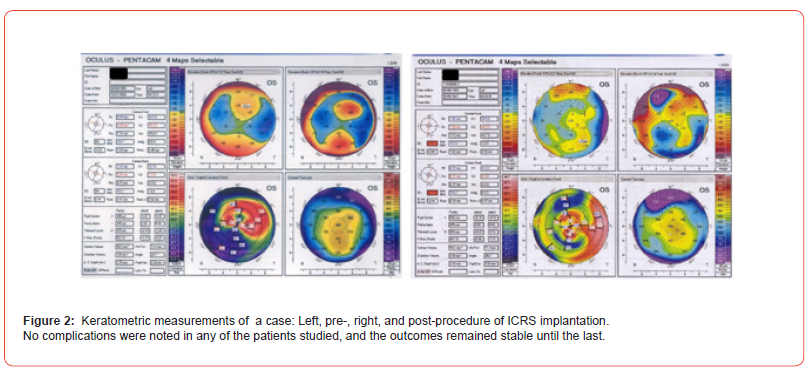

Implanting ICRS within the corneal stroma is a minimally invasive procedure with several advantages [4]. It allows for quick recovery, can be performed under local anesthesia, avoids incisionrelated complications, and may delay or even prevent the need for keratoplasty. These small synthetic devices work by spacing the corneal collagen fibers, flattening the central cornea through an arc-shortening effect, and adjusting the cornea’s refractive power to improve vision. The concept of using ICRS to flatten the central cornea and correct asymmetry was first proposed in 1966 [5]. It was introduced into clinical practice in 2000 [6], and subsequent research confirmed its effectiveness in reducing keratometric values (Figure 2), improving refraction, and enhancing visual acuity. ICRS was FDA-approved in 2004, and several variations and modifications have been introduced since then. Currently, five types of ICRS are commonly used: Keraring, Keraring AS, Intacs (intrastromal corneal implants), Myo ring, and Ferrara. Each type offers distinct advantages and limitations. For example, the triangular design of the Ferrara ring helps reduce glare but provides less flexibility than other rings [7].

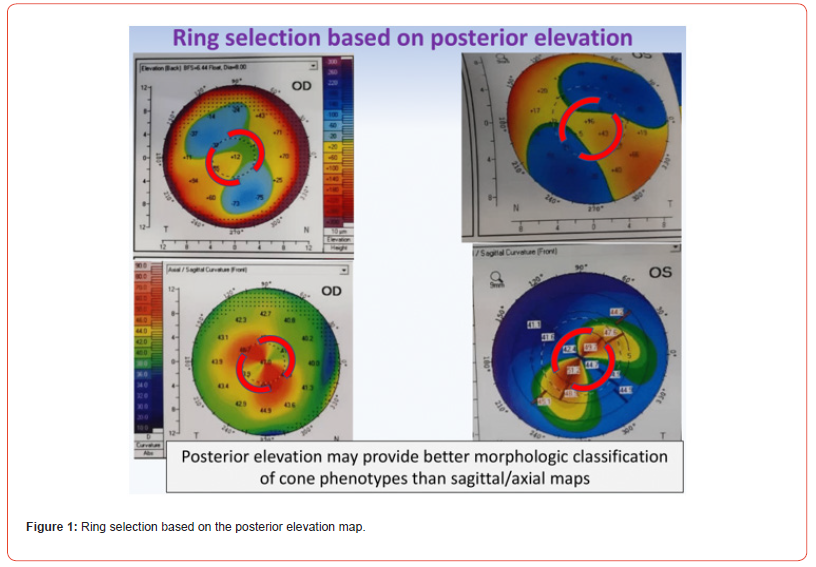

The need for long-term outcomes

Most studies report only short-term results [8, 9]. As such, further research is needed to assess this ring’s long-term safety and effectiveness according to the elevation map (Figure 1). To address this, our case series aimed to evaluate both objective and subjective outcomes 5 years after ring implantation in patients with keratoconus (KCN). We investigated visual, refractive, corneal topographic, aberrometric, and pachymetric changes, as well as patient satisfaction, using a validated questionnaire [10, 11].

Materials and Methods

Study setting and subjects

Based on comprehensive physical examination, adult patients referred to our clinic with decreased visual acuity and a diagnosis of KCN were considered for corneal ring implantation under specific conditions. Eligible patients were required to have no systemic diseases and normal results from other ocular examinations, including fundoscopy and intraocular pressure measurements. Implantation was considered for individuals who were intolerant to contact lenses, unresponsive to corrective spectacles, and unable to manage the complications associated with corneal transplantation or accept new methods [12].

We included patients who met the following inclusion criteria: age over 21 years, a clear central cornea, corneal thickness of at least 450 μm at the incision site, and absence of corneal scarring, edema, or hydrops. Additional eligibility criteria require a keratometry value of less than 65 diopters (D) and a pupil diameter of 7.0 mm or less in dim lighting conditions. Exclusion criteria included any history of collagen vascular disease, autoimmune disorders, immunodeficiencies, severe atopy, recurrent corneal erosions, habitual eye rubbing, or pregnancy. Prior to surgery, patients were thoroughly informed to ensure that they had realistic expectations regarding the potential outcomes of the procedure.

Surgical technique

Surgery was performed by a single expert surgeon (M.GH). Patients were positioned supine and received topical anesthesia (proparacaine eye drops) in the affected eye. After a 10-minute waiting period to confirm the effectiveness of the anesthesia, an incision was made based on the topographic map of the cornea. Using the Intralase FS 60 FSL system (Johnson & Johnson Vision), the surgeon created stromal tunnels by first marking the center of the pupil on the slit lamp. The vacuum suction ring was applied to the eye to secure it, followed by FS photo disruption to form a continuous circular tunnel approximately 80% of the way through the corneal depth. Subsequently, the ring segments were inserted into the tunnels and centered using a hook. Postoperatively, patients were prescribed tobramycin-dexamethasone eye drops, to be used every 6 hours for 1 week, along with polyethylene glycol 0.4% and propylene glycol 0.3% drops, to be used every 6 hours for 1 month.

Outcome measures

The patient’s demographics, including age, sex, history, and chief complaint, were recorded. Intra- and postoperative complications were recorded, which included overcorrection and difficulty in near vision. Keratometric, refractive, and aberration values were measured using Pentacam. Patients’ QOL was evaluated using the National Eye Institute Refractive Error Quality of Life (NEI-RQL) questionnaire. This instrument comprises 25 core items, along with additional optional questions. All items were explained to the patients by the study staff, and for those with impaired vision, the questions were read aloud as needed. The questionnaire subscales were scored on a scale from 0 to 100, with higher scores indicating better function. Scoring was performed according to the guidelines outlined by the original authors. The Persian version of the questionnaire used in this study had been previously validated [13].

Results

Demographic and baseline characteristics and visual outcomes

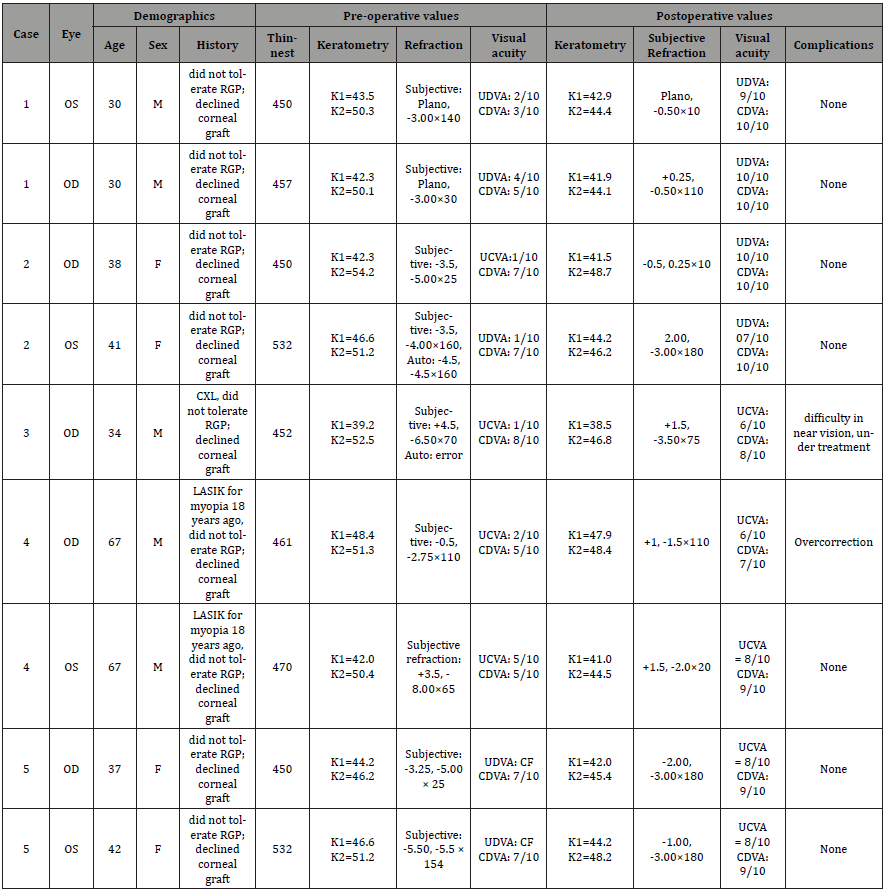

The demographic characteristics of the studied patients are summarized in Table 1.

The keratometric measurements of one case (pre- and postprocedure) are presented in Figure 2.

Table 1:Pre-and postoperative characteristics of the studied patients.

OS: oculus sinister (left eye); UDVA: uncorrected distance visual acuity; CDVA: corrected distance visual acuity; OD: oculus dexter (right eye); KCN: keratoconus; CXL: crosslinking; ICRS: intracorneal ring segments; PRK: photorefractive keratectomy; IOL; intraocular lens; BCDVA: best corrected distant visual acuity; RGP: rigid gas permeable lens; BCSVA: best spectacle-corrected visual acuity; LASIK: laser-assisted in situ keratomileusis; OU: oculus uterque (both eyes).

Discussion

Visual and refractive outcomes compared to literature

Decreased visual acuity is the chief complaint among patients with KCN, and improving visual acuity remains the primary goal of treatment. Our study observed favorable visual outcomes, with most patients achieving a best-corrected visual acuity (BCVA) of 10/10. However, one patient experienced overcorrection, and another reported difficulty with near vision, which was addressed with corrective spectacles. A well-documented challenge with ICRS implantation is the unpredictability of visual and refractive outcomes, such as residual myopia or astigmatism. This may result from insufficient reduction of corneal steepness [14, 15]. KCN progression following ICRS implantation can also lead to suboptimal visual results [16, 17]. In such cases, further interventions may be necessary, including the removal of a segment, replacement with a different segment, repositioning, or laser photoablation [18-21], as well as the addition of other intrastromal rings (a segment or an entire ring) [22, 23].

Due to the limitations and potential complications associated with ICRS, multiple ring types have been developed to address various indications and patient characteristics. In our study, we used a posterior elevation map (Figure 1), and our 5- year follow-up showed that favorable outcomes remained stable over this period. A multicenter study across four Spanish ophthalmic centers involving 31 eyes of 25 patients demonstrated that implantation of AJL Pro+ rings, with varying thicknesses and base diameters, resulted in significant improvements in uncorrected visual acuity (UCVA), corrected distance visual acuity (CDVA), and spherical equivalent, with positive results sustained at 3 months postoperatively [9]. A pilot study confirmed the efficacy of AJL Pro+ in controlling primary coma aberration in mild to moderate KCN, particularly in cases where there was a discrepancy in topographic and comatic axes between 30° and 105° [9]. Another study involving 35 eyes of 27 KCN patients reported significant improvements in manifest sphere and cylinder, spherical equivalent, overall blur strength, and CDVA, which persisted up to 3 months after surgery [8]. Another study indicated that CDVA improved significantly from 0.32 ± 0.19 to 0.12 ± 0.12 logMAR and UCVA from 0.75 ± 0.38 to 0.37 ± 0.24 logMAR at six months post-AJL Pro+ implantation, with 87% of eyes gaining at least one line of CDVA [24].

Quality of life outcomes

A distinctive feature of our study was the evaluation of patients’ QOL, offering insight into the subjective outcomes of ICRS implantation. Previous studies have assessed QOL for other ICRS types, notably the intrastromal Keraring [25-27]. Using the NEIRQL questionnaire, studies have demonstrated the positive effects of Keraring on QOL in KCN patients. For example, Paranhous et al. reported improvements in low-order root mean square (RMS) values and contrast sensitivity, especially at 6 cycles per degree (cpd), along with enhanced visual outcomes 4-8 months after surgery [26]. Another study reported significant improvements across all NEI-RQL scales and BCVA, spherical refraction, cylinder component, spherical equivalent, Kmax, and RMS low-order aberrations post-surgery. The authors noted that each 1D reduction in cylinder power corresponded to a 5-point improvement in general NEI-RQL scores, and normal contrast sensitivity at 3 and 6 cpd was associated with visual QOL [27]. Other QOL assessment tools, such as the NEI-VFQ 25, have also shown that improvements in BCVA and UCVA, as well as reductions in Kmax values following intrastromal ICRS implantation, correlate significantly with QOL scores [25]. These findings confirm the positive impact of ICRS, on the QOL of patients with KCN. Another study suggests that the VFQ- 25 composite score increased from 55.1 to 80.4 at one-year post- ICRS implantation, with a notable correlation between visual acuity and QOL [28].

Use of femtosecond laser

Our study’s use of FSL for tunnel creation likely contributed to the favorable results observed. As previously noted, FSL-based ICRS implantation offers several advantages over mechanical techniques and keratoplasty, including quicker recovery and fewer incision-related complications [29, 30]. A meta-analysis comparing mechanical and FSL-assisted ICRS implantation reported significant improvements in visual acuity and keratometry following both techniques but much lower complication rates in the FSL-assisted technique [31]. These benefits are likely due to the precise tunnel creation without direct eye manipulation. A study highlighted FSL’s precision in epithelial remodeling, with measurements such as +11.33 μm ± 12.95 [24]. The disposable device used with the FSL system creates a coupling interface across the cornea, enabling accurate focusing of the laser beam and dissection at the desired depth.

Strength, limitations and future directions

One of the key strengths of our study is the extended followup period of 5 years. Furthermore, our study reports on the QOL outcomes associated with ICRS implantation according to the elevation map. Despite these strengths, our study has some limitations, including the small sample size, which restricts the ability to conduct more detailed statistical analysis and limits the generalizability of the findings.

Conclusion

This study demonstrated significant improvements across all NEI-RQL scales and the overall score, 5-year postoperatively, along with recovery in BCVA, keratometric values, contrast sensitivity, and high and low-order aberrations following ICRS implantation.

Acknowledgement

None.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, or publication of this article. This work is entirely the authors’ own, reflecting their individual efforts and ideas.

References

- Santodomingo Rubido J, Carracedo G, Suzaki A, Villa Collar C, Vincent SJ, et al. (2022) Keratoconus: An updated review. Cont Lens Anterior Eye 45(3): 101559.

- Niazi S, Jiménez García M, Findl O, Gatzioufas Z, Doroodgar F, et al. (2023) Keratoconus Diagnosis: From Fundamentals to Artificial Intelligence: A Systematic Narrative Review. Diagnostics (Basel) 13(16): 2715.

- Andreanos KD, Hashemi K, Petrelli M, Droutsas K, Georgalas I, et al. (2017) Keratoconus treatment algorithm. Ophthalmol ther 6(2): 245-62.

- Niazi S, Gatzioufas Z, Doroodgar F, Findl O, Baradaran Rafii A, et al. (2024) Keratoconus: exploring fundamentals and future perspectives-a comprehensive systematic review. Ther Adv Ophthalmol 16:25158414241232258.

- Blavatskaya E (1968) Intralamellar homoplasty for the purpose of relaxation of refraction of the eye. Arch Soc Am Ophthalmol Optom 6: 311-325.

- Colin J, Cochener B, Savary G, Malet F (2000) Correcting keratoconus with intracorneal rings. J Cataract Refract Surg 26(8): 1117-1122.

- Siganos D, Ferrara P, Chatzinikolas K, Bessis N, Papastergiou G (2002) Ferrara intrastromal corneal rings for the correction of keratoconus. J Cataract Refract Surg 28(11): 1947-1951.

- Kammoun H, Piñero DP, Álvarez de Toledo J, Barraquer RI, García de Oteyza G (2021) Clinical Outcomes of Femtosecond Laser-Assisted Implantation of Asymmetric ICRS in Keratoconus with No Coincidence of Topographic and Comatic Axes. J Refr Surg 37(10): 693-699.

- Sardiña RC, Arango A, Alfonso JF, de Toledo JÁ, Piñero DP (2021) Clinical evaluation of the effectiveness of asymmetric intracorneal ring with variable thickness and width for the management of keratoconus. J Cataract Refract Surg 47(6): 722-730.

- Rabinowitz YS, Li X, Ignacio TS, Maguen E (2006) INTACS inserts using the femtosecond laser compared to the mechanical spreader in the treatment of keratoconus. J Refract Surg: 764-771.

- Ertan A (2006) Intacs for keratoconus comparison of mechanical versus femtolaser channel dissection. AAO, Las Vegas, NV, USA.

- Niazi S, Moshirfar M, Doroodgar F, Alió Del Barrio JL, Jafarinasab MR, et al. (2023) Cutting Edge: Corneal Stromal Lenticule Implantation (Corneal Stromal Augmentation) for Ectatic Disorders. Cornea 42(12): 1469-1475.

- Pakpour AH, Zeidi IM, Saffari M, Labiris G, Fridlund B (2013) Psychometric properties of the national eye institute refractive error correction quality-of-life questionnaire among Iranian patients. Oman j Ophthalmol 6(1): 37-43.

- Alió JL, Shabayek MH, Belda JI, Correas P, Feijoo ED (2006) Analysis of results related to good and bad outcomes of Intacs implantation for keratoconus correction. J Cataract Refract Surg 32(5): 756-761.

- Park J, Gritz DC (2013) Evolution in the use of intrastromal corneal ring segments for corneal ectasia. Curr Opin Ophthalmol 24(4): 296-301.

- Vega Estrada A, Alió JL, Plaza Puche AB (2015) Keratoconus progression after intrastromal corneal ring segment implantation in young patients: Five-year follow-up. J Cataract Refract Surg 41(6): 1145-1152.

- Al Bdour M, Abu Ameerh M, Gharaibeh A, AlQudah R, Hubaishy L, et al. (2024) Intrastromal corneal ring segments for keratoconus patients: up to 12 years follow up. Int Ophthalmol 44(1): 50.

- Alió JL, Piñero DP, Söğütlü E, Kubaloglu A (2010) Implantation of new intracorneal ring segments after segment explantation for unsuccessful outcomes in eyes with keratoconus. J Cataract Refract Surg 36(8): 1303-1310.

- Bali SJ, Chan C, Hodge C, Sutton G (2012) Intracorneal Ring Segment Reimplantation in Keratectasia. Asia Pac J Ophthalmol (Phila) 1(6): 327-330.

- Kremer I, Aizenman I, Lichter H, Shayer S, Levinger S (2012) Simultaneous wavefront-guided photorefractive keratectomy and corneal collagen crosslinking after intrastromal corneal ring segment implantation for keratoconus. J Cataract Refract Surg 38(10): 1802-1807.

- Torquetti L, Ferrara G, Almeida F, Cunha L, Ferrara P, et al. (2013) Clinical outcomes after intrastromal corneal ring segments reoperation in keratoconus patients. Int J Ophthalmol 6(6): 796-800.

- Coskunseven E, Kymionis GD, Grentzelos MA, Karavitaki AE, Portaliou DM, et al. (2010) INTACS followed by KeraRing intrastromal corneal ring segment implantation for keratoconus. J Refract Surg 26(5): 371-374.

- Behrouz MJ, Hashemian H, Khodaparast M, Rad AS, Shadravan M (2013) Intacs Followed by MyoRing Implantation in Severe Keratoconus. J Refract Surg 29(5): 364-366.

- Benlarbi A, Kallel S, David C, Barugel R, Hays Q, et al. (2023) Asymmetric Intrastromal Corneal Ring Segments with Progressive Base Width and Thickness for Keratoconus: Evaluation of Efficacy and Analysis of Epithelial Remodeling. J Clinic Med12(4): 1673.

- Penbe A, Karagöz IK, Kubaloğlu A, Sarı ES (2018) Long-Term Quality of Life Results of Intrastromal Corneal Ring Segment Implantation in Keratoconus Patients Using the National Eye Institute Visual Function Questionnaire. South Clin Ist Euras 29(1).

- Paranhos JdFS, Ávila MP, Paranhos A, Schor P (2010) Evaluation of the impact of intracorneal ring segments implantation on the quality of life of patients with keratoconus using the NEI-RQL (National Eye Institute Refractive Error Quality of life) instrument. Br J Ophthalmol 94(1): 101-105.

- Paranhos JdFS, Paranhos Jr A, Ávila MP, Schor P (2011) Analysis of the correlation between ophthalmic examination and quality of life outcomes following intracorneal ring segment implantation for keratoconus. Arq Bras Oftalmol 74: 410-413.

- Rodrigues PF, Moscovici BK, Hirai F, Mannis MJ, de Freitas D, et al. (2024) Vision-Related Quality of Life in Patients with Keratoconus with Enantiomorphic Topography After Bilateral Intrastromal Corneal Ring Implantation. Cornea 43(2): 190-194.

- Jabbarvand M, SalamatRad A, Hashemian H, Mazloumi M, Khodaparast M (2013) Continuous intracorneal ring implantation for keratoconus using a femtosecond laser. J Cataract Refract Surg 39(7): 1081-1087.

- Callou TP, Garcia R, Mukai A, Giacomin NT, de Souza RG, et al. (2016) Advances in femtosecond laser technology. Clin ophthalmol 10: 697-703.

- Struckmeier AK, Hamon L, Flockerzi E, Munteanu C, Seitz B, et al. (2022) Femtosecond Laser and Mechanical Dissection for ICRS and MyoRing Implantation: A Meta-Analysis. Cornea 41(4): 518-537.

-

Seyed Mohammad Ghoreishi, MD, Sana Niazi, MD, MPH, PhD, Maedeh Mazloomi, MD and Farideh Doroodgar*, MD, MPH, FICO. Visual Outcomes and Subjective Satisfaction After Intracorneal Ring Segment Implantation in Patients with Keratoconus. W J Opthalmol & Vision Res. 5(2): 2025. WJOVR.MS.ID.000609.

-

Visual outcomes, Visual acuity, Eye institute, Keratoconus, Corneal stroma, Ocular examinations, Pupil diameter, Myopia, Cornea

-

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.