Research Article

Research Article

A comparative analysis of digital screen type preference and accommodation parameters in Gen z and Millennials

Saleha Zubair1, Rubina Shah OD FAAO2*

1BSc. (Hons) Vision Sciences (Optometry)

2National Eye Center Lahore

Rubina Shah OD FAAO, National Eye Center Lahore, Pakistan.

Received Date:July 15, 2025; Published Date:July 24, 2025

Abstract

Purpose: To compare the population of Generation Z and Millennials to assess screen type preferences, screen type in use, near working

distance used, and digital eye strain, along with the evaluation of near point of convergence and accommodation parameters.

Method: A comparative cross-sectional study was conducted in the National Eye Center, Lahore, from April 2024 to August 2024 with a sample

size of 260 (130 Generation Z and 130 Millennials). The sample size was calculated using a formula whose significance level (α) is 5%, precision level (d) is 0.1, and level of confidence is 95%. Digital screen users, aged 12-43 years, with a minimum of 6 hours of screen time, no history of ocular surgery, and a BCVA of 6/6 were included in this study. The data on digital screen type preference and eye strain were collected through a questionnaire after obtaining informed consent. All the accommodative parameters were collected subjectively by using the RAF ruler, trial box (lenses and eye frame), near reading target, and ±2 flippers. Data were entered and analyzed using SPSS software, version 26. Qualitative variables: age group, gender, device type, usage purpose, headache, blurring, eyestrain, preferred screen, working distance, eye pain, tracking issues; quantitative variables: screen time, NPA, AA, AF, PRA, NRA, NPC. The data was recorded on the proforma attached to the questionnaire. The data were analyzed using SPSS software, version 26. P value ≤ 0.05 was considered significant.

Results: In comparative analysis, there were significant results for near point of convergence (p=0.019), near point of accommodation (NPA,

p=0.000), amplitude of accommodation (AA, p=0.000) accommodation facility (AF, p=0.000), positive relative accommodation (PRA, p=0.000),

negative relative accommodation (NRA, p=0.0476), screen type preferences (p=0.007), headache (p=0.003), blurry vision (p=0.003), eyestrain

(p=0.013), screen viewing distance (p=0.003), eye pain (p=0.005), and far-tracking issues (p=0.032).

Conclusion: Both generations preferred smartphones as their choice of digital screen and their near point of convergence, with some

accommodation parameters, i.e., NRA and PRA values slightly higher than normal. In contrast, AF was lower than normal, and the amplitude of

accommodation was lower for the older individuals in both groups.

Keywords:Generation Z; Millennials; Digital Screen; Digital Eye Strain; Near Point Convergence; Near Point Accommodation; Amplitude of Accommodation; Accommodation Facility; Negative Relative Accommodation; Positive Relative Accommodation

Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic has skyrocketed screen time for essential life tools like work, education, and entertainment, creating a digitally dominated world [1]. The chores like shopping and banking became easier with the rise of digital electronic devices [2]. These advantages have increased the ownership of digital devices at an exponential rate, with the ownership of digital devices, especially smartphones, having increased from 12.7 million to over 5.4 billion people in the past 20 years [3].

In the world of artificial intelligence, competition among different organizations for digital inventions has also increased to meet consumers’ demands in the global market. Generation Z is the generation born between 1997 and 2012. They are the digital natives born with the internet. Generation Y, also known as Millennials, refers to individuals born between 1981 and 1996. This is the first generation to grow up with digital media [4]. A survey conducted at the State University of New York showed that 50 percent of the surveyed population of Gen Z had screen time for more than 9 hours a day, and almost all had ownership of smartphones [5].

The outstanding impact of various features of these devices, combined with digital media, has increased the duration of screen time for screen users [6]. Since the 2019 COVID lockdown, the screen time in China and Poland has also increased significantly [7]. The screens for performing near tasks vary in their sizes, from smartphones with an average size of 7 inches to desktops as big as 32 inches or larger [8].

The excessive use of digital screens has resulted in visual discomfort, known as “digital eye strain,” also referred to as “Computer Vision Syndrome,” abbreviated as CVS [9]. There are different approaches to reduce asthenopic symptoms, e.g., behavioral modifications, protecting eyes from blue rays, taking breaks while using digital screens, blinking periodically, and following the 20-20-20 rule [10].

The parameters, such as the accommodation facility (AF), are also affected by excessive screen time [11]. The changes in accommodative parameters can be the result of extended screen time. With technological advancements and progress in the digital media industry, smartphone adoption has become widespread, offering mobile digital screens with various features and applications [12, 13].

Method

The research was approved by Ethical Review Board of College of Ophthalmology and Allied Vision Sciences, Mayo Hospital. A comparative cross-sectional study was conducted that took place in National Eye Centre Lahore, Pakistan from April 2024 to August 2024. Sample size was calculated using a formula whose significance level (α) is 5%, precision level (d) is 0.1 and level of confidence is 95% [14]. The sample size was 260 (130 Generation Z individuals and 130 Millennials). Non-probability convenient sampling was applied. Subjects having any history of ocular surgery, screen hours < 6 hours and age not ranging from 12- 43 years were excluded from the study. The included subjects had BCVA of 6/6 (on snellen chart) and near visual acuity of N-6 on Jaeger chart were included. Patients fulfilling the inclusion criteria were enrolled after informed consent. All the demographic data, digital eye strain symptoms and values of near point of convergence and accommodative parameters were recorded. The subjects were given brief about impact of screen time and its impact on eye strain and accommodative parameters. All the accommodative parameters were collected subjectively by using RAF ruler, trial box (lenses and eye frame), near reading target and ±2 flippers. All the findings were written on a proforma for research purpose. Data was entered and analyzed using SPSS software 26. Qualitative variables like gender, age, device type, usage purpose, headache, blurring, eyestrain, preferred screen, working distance, eye pain, tracking issues are presented as frequency and percentages. Quantitative variables like screen time, NPA, AA, AF, PRA, NRA, NPC are presented as means ± standard deviation. Chi- Square test and Mann-Whitney test were applied for spss analysis. P value ≤0.05 was considered significant.

Results

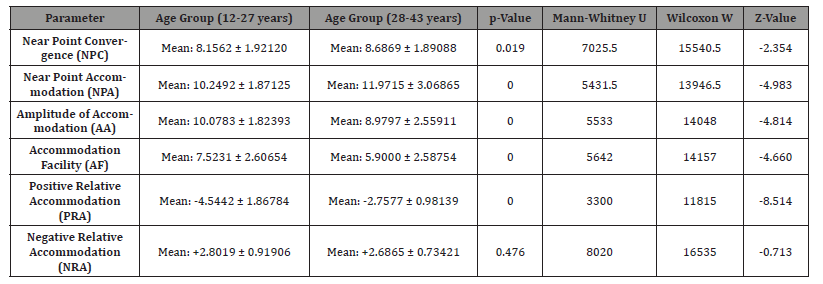

In comparative analysis Millennials had higher NPC (p=0.019) and NPA (p=0.000) values than Generation Z, both within normal ranges. The Generation Z showed greater AA (p=0.000), AF (p=0.000), PRA (p=0.000), and NRA (p=0.0476). AF was slightly below normal for both groups, and PRA and NRA were slightly above normal. Both generations preferred smartphones and questions such as screen type preference (p=0.007), headache (p=0.003), blurring (p=0.003), eyestrain (p=0.013), near viewing distance (p=0.003), eye pain (p=0.005), and far tracking issues (p=0.032) showed significant differences.

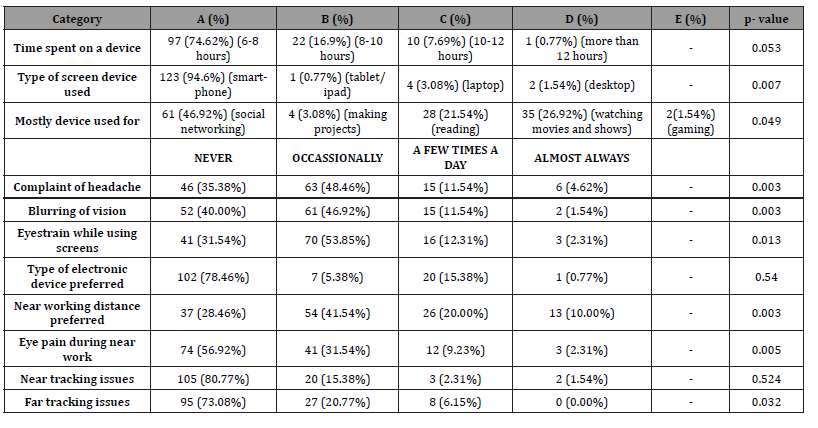

Table 1:Statistical Analysis of Questions for Generation Z.

Age Group: 12–27 Years

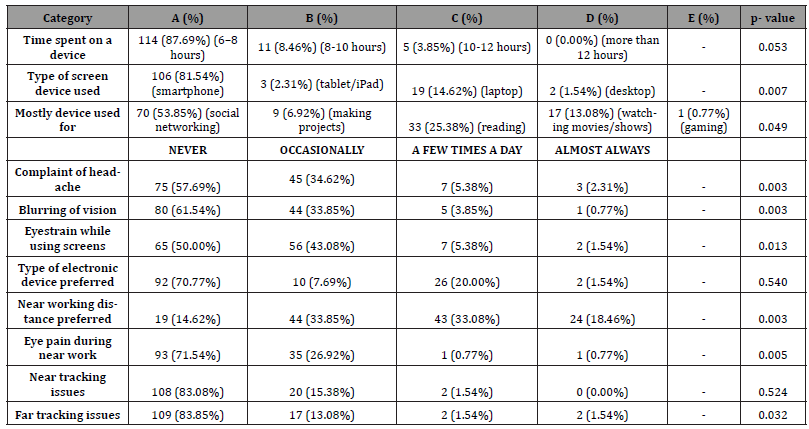

Table 2:Statistical Analysis of Questions for Millineals.

Age Group: 28-43 Years

Table 3:Discriptive Data for Accommodative Parameters.

Age Group: 28-43 Years

Discussion

This study was comparative cross-sectional type and a comparative analysis was done between two generational cohort groups: Gen-Z and Millenials to compare digital screen type preference and accommodation parameters..

In this study, Millennials (33.85%) and Gen Z (41.54%) most frequently favored a working distance of 30-35 cm (p = 0.003). Similarly, Jennifer Long and co. found that average viewing distance in 18 young adults after using smartphones for 1 hour was 29.2 ± 7.3cm [15]. Both studies found that longer screen times were associated with greater digital eye strain at closer viewing distances.

In my study involving 260 participants, 53.8% of Gen Z and 43.1% of Millennials reported eye strain (p=0.013) and all of them had screen time of ≥ 6 hours a day. A study among Hong Kong children and adolescents occurred in 2023 found that out of 1508 students 53.3% reported eye strain and 38.9% experienced blurred vision while using smartphones [16]. They had screen time of ≥4 hours. The younger individuals in the 2023 study were in the same age range as the Gen Z people in my study.

Majority of Generation Z participants (74.62% of 130 participants) reported spending 6-8 hours daily as screen users. Most of the Millenials (87.69%) also used screen in between 6-8 hours. There was no significant difference for the comparison of screen time. However, a survey conducted for US students [17]. specifically for digital screen users for individuals ranging from 14-17 years showed that 43.57% of 25,720 participants had screen time of ≥ 4 hours a day. Their p-value= 0.0012 showed rise in screen time contrary to my comparison of two cohort (p= 0.053) However their average screen time was lesser than the individuals of same age from generation z.

Most of the participants focused screen use for social networking (46.92% Gen Z (n=130), 53.85% Millennials (n=130)) just as a survey [18]. stated that 842 university students with a mean age of 23.26 ± 4.1 years primarily used screen for social networking (80%). The gaming was less popular in my cohort (1.54% Gen Z, 0.77% Millennials). In contrast <50% of individuals from the previous study used digital devices for gaming.

64.62% of Gen Z and 42.31% of Millennials reported experiencing headaches during screen use (p = 0.003). Reem A and co. also found association of headache with screen time (p= 0.036) [19]. However, Ilaria Montagni and co [20]. found that migraine headaches were more common among both generations due to excessive screen usage.

In my study, blurred vision during screen use was significantly more common in Generation Z (60%) than Millennials (38.46%), with a p-value of 0.003. This study aligns with Usgaonkar and co [21]. who found strong association (p < 0.001) between screen use and blurred vision in 240 individuals (15-30 years). Their study aligns with mine as both highlighted that prolonged screen exposure can lead to or worsen blurring symptoms.

In my comparative analysis, 68.5% of Gen Z and 50% of Millennials reported DES (p = 0.013). Similar results were found by Pratyusha Ganne and her colleagues who conducted an online survey in 944 participants during COVID-19 pandemic [22]. They reported that 50.6% of students enrolled in online classes reported digital eye strain (DES), compared to 33.2% in the general population (p < 0.0001. Both studies show prolonged screen use significantly contributes to DES. According to my research, 28.46% of Millennials and 43.08% of Generation Z reported having eye pain, with Gen Z reporting complain for eye pain (p = 0.005). In comparison, a study occurred in Nepal [23]. among 206 individuals showed that eye pain symptoms were not associated with screen use (p= 0.28). Particularly among Generation Z, my research shows a higher correlation between screen time and eye pain.

The individuals of Generation Z had lower Near Point of Accommodation (NPA) compared to Millennials, but within normal ranges (p=0.000). the comparison of both groups showed significant values for NPA and AA (p<0.001 for both). In my study, the parameter accommodation facility was most disturbed in both the groups(p=0.000). These findings align with a cross-sectional study [24]. among 82 young adults, aged between 19-26 years, linking screen use to accommodation changes. They found significant differences in Amplitude of Accommodation and Accommodation Facility between groups with varying visual fatigue levels (p < 0.05).

In my study, NRA values for Generation Z (2.80 ± 0.92) and Millennials (2.69 ± 0.73) showed no significant differences, suggesting this parameter was less impacted by screen exposure in both groups (p=0.476). Studies on smartphone and laptop use [25]. reported significant changes in Near Point of Accommodation (NPA) and Negative Relative Accommodation (NRA) after short screen exposure (p<0.05). Smartphone use notably increased NRA values. Similarly, a study [26] in The Korean Journal of Vision Science found significant changes in visual functions like amplitude, NRA, and binocular accommodative facility (p < 0.05) after adults viewed videos or read e-books on smartphones for a set period. Similarly, my research also highlights that extended screen use leads to noticeable shifts in accommodative performance.

Conclusion

This study with comparative analysis in Generation Z and Millenials showed that most of the members of these groups prefer smartphone as their electronic device of choice. There were no significant changes in values for NRA, screen type used mostly, device used mostly, digital device preferred and for complain of near tracking issues. However there were significant changes in NPC, NPA, AA, AF, PRA, screen time, mostly used screen type, headache, blurring, eyestrain, screen viewing distance, pain in eyes and far tracking issues.

Acknowledgement

None.

Conflict of Interest

None.

References

- Yates A, Starkey L, Egerton B, Flueggen F (2021) High school students’ experience of online learning during Covid-19: the influence of technology and pedagogy. Technol. Pedagog. Educ 30(1): 59-73.

- Liao S, Yu L, Kruger JL, Reichle ED (2024) Dynamic reading in a digital age: new insights on cognition. Trends Cogn Sci 28(1): 43-55.

- Mushroor S, Haque S, Riyadh AA (2020) The impact of smart phones and mobile devices on human health and life. Int J Community Med Public Health 1: 9-15.

- Soroya SH, Ameen K (2020) Millennials’ Reading behavior in the digital age: A case study of Pakistani university students. J Libr Admin 60(5): 559-577.

- Ahmed N Generation (2019) Z’s smartphone and social media usage: A survey. J Mass Commun 9(3): 101-22.

- Granic I, Morita H, Scholten H (2020) Beyond screen time: Identity development in the digital age. Psychol Inq 31(3): 195-223.

- Sultana A, Tasnim S, Hossain MM, Bhattacharya S, Purohit N (2021) Digital screen time during the COVID-19 pandemic: a public health concern. F1000Res: 10: 81.

- Kang JW, Chun YS, Moon NJ (2021) A comparison of accommodation and ocular discomfort change according to display size of smart devices. BMC Ophthalmol 21: 1-9.

- Gupta R, Chauhan L, Varshney A (2021) Impact of e-schooling on digital eye strain in coronavirus disease era: a survey of 654 students. J Curr Ophthalmol 33(2): 158-64.

- Tangmonkongvoragul C, Chokesuwattanaskul S, Khankaeo C, Punyasevee R, Nakkara L, (2022). Prevalence of symptomatic dry eye disease with associated risk factors among medical students at Chiang Mai University due to increased screen time and stress during COVID-19 pandemic. PLoS One 17(3): e0265733.

- Nayak R, Sharma AK, Mishra SK, Bhattarai S, Sah NK, (2020). Smartphone induced eye strain in young and healthy individuals. J Kathmandu Med Coll 201-206.

- Mylona I, Glynatsis MN, Floros GD, Kandarakis S (2023) Spotlight on digital eye strain. Clin Optom 29-36.

- Bröhl C, Rasche P, Jablonski J, Theis S, Wille M, Mertens A, editors. Desktop PC, tablet PC, or smartphone? An analysis of use preferences in daily activities for different technology generations of a worldwide sample. Human Aspects of IT for the Aged Population Acceptance, Communication and Participation: 4th International Conference, ITAP 2018, Held as Part of HCI International 2018, Las Vegas, NV, USA, July 15–20, 2018, Proceedings, Part I 4; 2018: Springer.

- Yekta A, Hashemi H, Khabazkhoob M, Ostadimoghaddam H, Ghasemi Moghaddam S, et al. (2017) The distribution of negative and positive relative accommodation and their relationship with binocular and refractive indices in a young population. J Curr Ophthalmol 29(3): 204-209.

- Long J, Cheung R, Duong S, Paynter R, Asper L (2017) Viewing distance and eyestrain symptoms with prolonged viewing of smartphones. Clin Exp Optom 100(2): 133-137.

- Chu GC, Chan LY, Do Cw, Tse AC, Cheung T, et al. (2023) Association between time spent on smartphones and digital eye strain: A 1-year prospective observational study among Hong Kong children and adolescents. Environ Sci. Pollut Res 30(20): 58428-58435.

- Wu HT, Li J, Tsurumi A (2024) Change in screen time and overuse, and their association with psychological well-being among US-wide school-age children during the COVID-19 pandemic: analysis of the National Survey of Children’s Health (NSCH) years 2018-21. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry Ment Health 18(1):9.

- Atas AH, Çelik B (2019) Smartphone use of university students: Patterns, purposes, and situations. Malays. Online J Educ Technolo 7(2): 59-70.

- Alyoubi RA, Kobeisy SA, Souror HN, Alkhaldi FA, Aldajam MA, et al. (2020) Active screen time habits and headache features among adolescents and young adults in Saudi Arabia. Int J Pharm Res Allied Sci 81-86.

- Montagni I, Guichard E, Carpenet C, Tzourio C, Kurth T (2016) Screen time exposure and reporting of headaches in young adults: A cross-sectional study. Cephalalgia 36(11): 1020-1027.

- Usgaonkar U, Parkar SRS, Shetty A (2021) Impact of the use of digital devices on eyes during the lockdown period of COVID-19 pandemic. Indian J Ophthalmol 69(7): 1901-1906.

- Ganne P, Najeeb S, Chaitanya G, Sharma A, Krishnappa NC (2021) Digital Eye Strain Epidemic amid COVID-19 Pandemic-A Cross-sectional Survey. Ophthalmic Epidemiol 28(4): 285-292.

- Yaacob NSM, Abdullah AM, Azmi A (2022) Prevalence of Computer Vision Syndrome (CVS) Among Undergraduate Students of a Health-related Faculty in a Public University. MJMS 18.

- Sigamani S, Majumde r C, Sukumaran S (2022) Changes in accommodation with visual fatigue among digital device users. Med. hypothesis discov. innov Optom 3(2): 63-9.

- Pachiyappan T, Srambikkal SA (2023) Changes in Accommodation and Vergence Measurements After Smartphone Use in Healthy Young Adults. RGUHS J Allied Health Sci 3(2).

- Kang YJ, Leem HS (2015) Effects of smartphone usage with contents and smartphone addiction on accommodative function. Korean J Vis Sci 17(3): 289-297.

-

Saleha Zubair, Rubina Shah OD FAAO*. A comparative analysis of digital screen type preference and accommodation parameters in Gen z and Millennials. W J Opthalmol & Vision Res. 5(3): 2025. WJOVR.MS.ID.000611.

-

Computer Vision Syndrome, Vision Sciences, Eye pain, Visual fatigue levels, Headache, Blurring, Eyestrain, Visual functions, Binocular, Viewing distances

-

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.