Research Article

Research Article

Rate and Risk Profile of Deep Venous Thrombosis in Pregnancy and Postpartum Period Among Sudanese Women

Awadalla Mohammed Abdelwahid1, Samia Elhaj Elawad Abd Alla2, Hajar Suliman Ibrahim Ahmed3, Omer Mohamed Ali Mandar4 and Siddig Omer M Handady5*

1Assistant professor of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Faculty of Medicine, Al Neelain University, Sudan

2Specialist of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Shendi Teaching Hospital, Sudan

3Faculty of Medicine, Al Neelain University, Sudan

4Faculty of Medicine, Al Gadrif Maternity Hospital, Sudan

5Faculty of Medicine, Al Nahda University, Sudan

Siddig Omer M Handady, Associate Professor of Obstetrical & Gynecology, Faculty of Medicine - Al Nahda University, Ibrahim Malik teaching Hospital, Sudan.

Received Date: September 03, 2019 Published Date: September 13, 2019

Abstract

Background: Deep venous thrombosis (DVT) during pregnancy is associated with high mortality, morbidity, and costs. DVT can also result in long-term complications that include post thrombotic syndrome (PTS) adding to its morbidity.

Objective: To determine rate, timing and risk profile of deep venous thrombosis during pregnancy and puerperium among Sudanese women.

Methodology: It was prospective case control and hospital-based study carried out at Shendi Teaching and Elmec-Nimir University Hospitals -Sudan from March 2017 to March 2018. Seventy-eight pregnant women or in puerperium with Doppler confirmed deep venous thrombosis were enrolled in the study, representing the main study group, while another 156 pregnant women without DVT were selected as the control group.

Results: The current study showed the frequency of DVT was (0.622%), 78 out of 12,542 deliveries during the whole study period, with (0.176%) and (0.446%) occurring antenatal and postnatal respectively. The rate was 622 DVT per 100,000 births. This study revealed that women who are primigravida, had positive family history of VTE, had past history of DVT, had Anti phospholipids, anemia and delivered by C/S showed statistically significant association with DVT.

Conclusions: The prevalence of DVT in our study was 622 per 100 000 births per year in pregnant and postpartum women. There is an urgent need for prophylaxis measures against DVT for pregnant women who found at higher risk for DVT.

Keywords: Deep Venous thrombosis; Pregnancy; Postpartum; Rate; Risk profile; Sudanese women

Introduction

Venous thromboembolism is a leading cause of maternal death in developed and developing world. Venous thromboembolism can occur throughout pregnancy with an estimated antenatal and postnatal incidence of 6-12 and 3-7 per10, 000 maternities respectively. Over 40% of antenatal venous thromboembolism occurs in the first trimester of pregnancy [1].

The daily risk of venous thromboembolism is four-fold higher in post-natal period compared with antenatal period [2]. The factors which increase the risk of venous thromboembolism in pregnant and postnatal women are age more than 35, prime party, pre-eclampsia, varicose veins, obesity, cesarean section, previous VTE, family history of VTE , patients with inherited thrombophilias, excessive blood loss, long haul travel, prolonged labor, instrumental delivery and immobility after delivery [3].

Clinical diagnosis of deep venous thrombosis by, leg pain, swelling, tenderness, high temperature, oedema, lower abdominal pain and high total white blood cell count. It may also present with features of pulmonary embolism; dyspnea, chest pain, collapse, haemoptesis, fainting and increased jugular venous pressure [4].

Compression duplex ultrasound of the entire proximal venous system is considered the optimal first-line diagnostic test for DVT in pregnancy [5,6]. An apparently normal ultrasound examination in a patient with significant symptoms and signs or risk factors for VTE does not exclude a calf DVT, so serial ultrasound examinations should be repeated [7,8]. When iliac vein thrombosis is suspected because the woman reports back pain and swelling of the entire limb, pulsed Doppler, magnetic resonance venography, or conventional contrast venography should be considered [9,10]. This study attempts to determine rate, timing and risk profile of deep venous thrombosis during pregnancy and puerperium. among Sudanese women.

Materials and Methods

It was prospective case control and hospital-based study carried out at Shendi Teaching and Elmec-Nimir University Hospitals -Sudan from March 2017 to March 2018. Seventy eight pregnant women or in puerperium who presented with symptoms suggestive of DVT and Doppler confirmed deep venous thrombosis were enrolled in the study, representing the main study group, while another 156 pregnant women from the population of patients presenting to the same hospitals without symptoms of VTE were selected as the control group. Participants completed a questionnaire on personal data and clinical history. Questions regarding known risk factors for DVT such as age, parity, mode of delivery, family history or past history of VTE, medical disease history, personal history of antiphospholipid, sickle disease and thrombophilia. BMI was calculated which defined as the weight in kilograms divided by the square of the height in meters (kg/m2). The BMI was determined by using World Health Organization (WHO) classification for obesity.

Statistical analysis was performed via SPSS software (SPSS, Chicago, IL, USA). Continuous variables were compared using student’s t test (for paired data) or Mann–Whitney U test for nonparametric data. For categorical data, comparison was done using Chi-square test (χ²) or Fisher’s Exact test when appropriate. A P value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Ethical clearance and approval for conducting this research was obtained from the general manager of the hospitals and informed written consent was obtained from every respondent who agreed to participate in the study. The respondents informed that the study is not associated with experimental or therapeutic intervention while information was collected from them.

Results

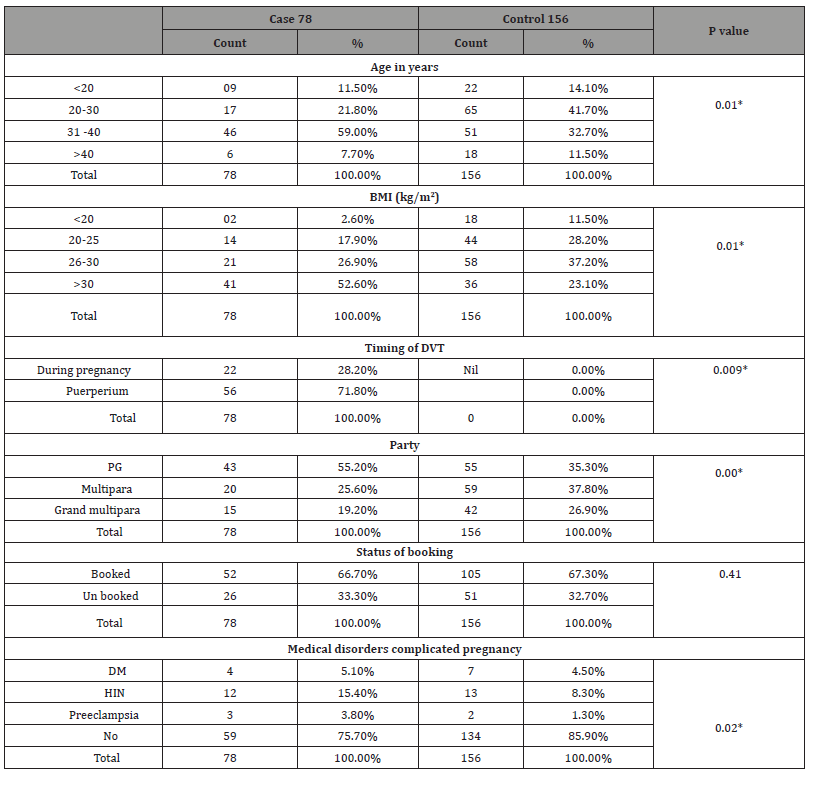

During the study period 12,542 deliveries occurred at Shendi Teaching and Elmec-Nimir University Hospitals, Sudan. The current study showed the rate of DVT was (0.622%) 78 out of 12,542 deliveries during the whole study period, with (0.176%) and (0.446%) DVT occurring antenatal and postnatal respectively. The rate was 622 DVT per 100,000 births (Table 1).

Table 1: Shows the nonparametric correlation between the two groups regarding demographic data and clinical characteristics.

*Statistically significant at 0.05 level

The mean of age was 36.31±2.88 among the case group, and it was 27.03±3.83 among the control group with significant differences. The mean BMI was 32±2 among the case group, and it was 24±2 among the control group with significant differences. Of the total 78 DVT patients, 43 (i.e., one-half) were primigravidae which showed statistically significant association with the disease and majority of women 157 (67.1%) were booking.

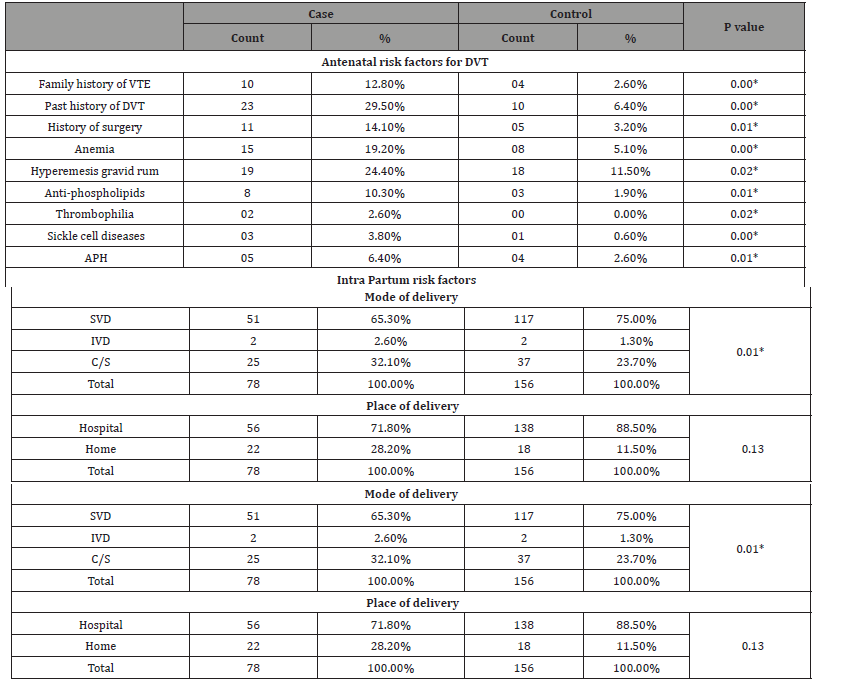

Regarding risk factors for DVT , Table 2 shows that , of the total 78 DVT patients, , 10 (12.85%) showed positive family history of VTE , 23(i.e., one-third ) showed past history of DVT and 11 (14.1%) showed history of surgery compared with 4 (2.6%) , 10 (6.4%) and 5 (3.2%) showed positive family history of VTE , past history of DVT and history of surgery among control group. Positive family history of VTE, past history of DVT and history of surgery showed statistically significant association with DVT (p value <0.05). Other risk factors such as ante partum hemorrhage, anemia, hyperemesis gravid rum, anti-phospholipids, Thrombophilia and Sickle cell diseases were higher in cases compared with control and showed significant differences between the two groups (p value <0.05). The percentage of women who underwent caesarian section were higher in the DVT group (32.1% vs. 23.7%; p value =0.00) compared with control group. PPH was higher in DVT patients compared to control group (5.1.% vs. 1.9%; p value =0.00). During the postpartum period, women with DVT had an increased percentage of postpartum infection (9.0% vs. 1.9%; p=0.00), postpartum anemia (17.9% vs. 5.8%; p=0.00) and prolong hospitalization (3.8% vs. 1.3%; p=0.03) compared with control group.

Table 2: Shows the nonparametric correlation between the two group regarding antenatal, intra partum and post-partum risk factors for DVT.

*Statistically significant at 0.05 level

Discussion

Many changes occur in pregnancy and contribute to hypercoagulability, Pregnancy can be considered a form of disseminated intravascular coagulation due to reduced fibrinolytic activity and increased platelet aggregation [3].

DVT during pregnancy and postnatal are increasing in prevalence and are associated with significant long-term psychological and physical maternal morbidity. It has significant problems that require skill and knowledge to limit potential adverse events.

The current study showed the rate of DVT was (0.622%) with (0.176%) and (0.446%) occurring antenatal and postnatal, respectively. The rate was 622 DVT per 100,000 births which is very high compared with two studies conducted in Sudan which , reported that , the prevalence of DVT in pregnant and postpartum women varied between 448 per 100 000 births per year [11] and 380 per 100 000 births per year [12]. Out of a total of 78 women had DVT, 28.2% occurred during pregnancy and this is due to changes exclusive of pregnancy, whereas in other 71.8% women they were occurred during puerperium. Our finding agrees with Yoo HHB, who reported that, the daily risk of venous thromboembolism is fourfold higher in post-natal period compared with antenatal period [2]. Also, our study was supported by Gader AA, who obtained same finding [11].

In this case-control study, the mean of age was 36.31±2.88 among the case group, and it was 27.03±3.83 among the control group. Association between advanced age as risk factor for DVT was statistically significant. Similarly, studies by James AH and Simpson EL showed significant association between age as risk factor for DVT [13,14].

In our study, high BMI was a significant risk factor associated with DVT. Similar observations were showed in previous studies by Simpson EL, et al. and Ohira T, et al. [14,15].

The current study revealed that, there was high significant association between positive past history of DVT and development of the disease, which was comparable to different studies done by Gader AA and Haggaz AA [11,12].

The intra partum parameters such as prolonged labor, operative vaginal delivery, caesarian section and PPH were significantly high in DVT patients as compared to control group and were considered as the risk factors for DVT. Various studies reported that, prolong labor, operative vaginal delivery, caesarian section is more prone for the risk of DVT [11,12,16].

This study revealed that women who are primigravida, had positive family history of VTE, had past history of DVT and with history of surgery showed statistically significant association with DVT. This is consistent with study done in 11 Norwegian counties [17], who reported that, antenatal risk factors were, age older than 35 years, prime parity. Postnatal risk factors were cesarean section, preeclampsia, assisted reproduction, abruption placenta, and placenta previa.

Deep vein thrombosis was found in women delivered by VD 67.9 % compared with 32.1% that delivered by CS which is comparable to Jacobsen AF [17] who revealed that, incidence of venous thromboembolism is probably two to four times higher after cesarean sections when compared to normal and forceps deliveries [17,18]. On the same point of view, our finding was supported by Gader AA, who reported that cesarean delivery was a predictor for DVT (OR = 2.21; 95% CI = 1-4.40, P = 0.02. Cesarean section is a known risk factor for DVT [11].

Conclusion

The prevalence of DVT in our study was 622 per 100 000 births per year in pregnant and postpartum women. We found different ante- and postnatal risk profile. Positive family history of VTE, past history of DVT and history of surgery were significant antenatal risk factors; whereas prolong labor, cesarean section, PPH, postpartum infection and postpartum anemia were strong postnatal risk factors. There is an urgent need for prophylaxis measures against DVT for pregnant women who found at higher risk for DVT.

Acknowledgement

None.

Conflict of Interest

No conflict of interest.

References

- Silveira PR (2012) Deep vein thrombosis and pregnancy: etiopathogenic and therapeutic aspects. J Vasc Bras 1: 65-70.

- Yoo HH (2007) Investigating pulmonary thromboembolism in pregnancy. Pneumol Paulista 20: 6-7.

- (2004) Thromboprophylaxis during pregnancy, labor and after vaginal delivery. London (UK): Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (RCOG): 37: 1-13.

- Hach-Wunderle V (2013) Venous thrombosis in pregnancy. Vasa 32(2): 61-68.

- Andersen BS, Steffensen FH, Sørensen HT, Nielsen GL, Olsen J (2012) The cumulative incidence of venous thromboembolism during pregnancy and puerperium--an 11-year Danish population-based study of 63,300 pregnancies. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 77(2): 170-173.

- Gherman RB, Goodwin TM, Leung B, Byrne JD, Hethumumi R, et al. (2013) Incidence, clinical characteristics, and timing of objectively diagnosed venous thromboembolism during pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol 94(5 Pt 1): 730-734.

- Larsen TB, Sørensen HT, Gislum M, Johnsen SP (2012) Maternal smoking, obesity and risk of venous thromboembolism during pregnancy and the puerperium: a population-based nested case-control study. Thromb Res 120(4): 505-509.

- Bates SM, Jaeschke R, Stevens SM, Goodacre S, Wells PS, et al. (2012) Diagnosis of DVT: Antithrombotic Therapy and Prevention of Thrombosis, 9th ed: American College of Chest Physicians Evidence-Based Clinical Practice Guidelines. Chest 141(2 Suppl): e351S-e418S.

- Thomson AJ, Greer IA (2007) RCOG Green Top Guideline No. 29 Thromboembolic Disease in Pregnancy and the Puerperium: Acute Management. London, United Kingdom: RCOG.

- To MS, Hunt BJ, Nelson-Piercy C (2008) A negative D-dimer does not exclude venous thromboembolism (VTE) in pregnancy. J Obstet Gynaecol 28(2): 222-223.

- Gader AA, Haggaz AE, Adam I (2009) Epidemiology of deep venous thrombosis during pregnancy and puerperium in Sudanese women. Vasc Health Risk Manag 5(1): 85-87.

- Haggaz AA, Mirghani OA, Adam I (2003) Venous thromboembolism in pregnancy and the puerperium in Sudanese women. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 83(3): 309-810.

- James AH, Tapson VF, Goldhaber SZ (2005) Thrombosis during pregnancy and the postpartum period. Am J Obstet Gynecol 193(1): 216-219.

- Simpson EL, Lawrenson RA, Nightingale AL, Farmer RD (2001) Venous thromboembolism in pregnancy and the puerperium: incidence and additional risk factors from a London perinatal database. BJOG 108(1): 56-60.

- Ohira T, Cushman M, Tsai MY, Zhang Y, Heckbert SR, et al. (2007) Folsom ARABO blood group, other risk factors and incidence of venous thromboembolism: The Longitudinal Investigation of Thromboembolism Etiology (LITE). J Thromb Haemost 5(7): 1455-1456.

- Dargaud Y, Rugeri L, Fleury C, Battie C, Gaucherand P, et al. (2017) Personalized thromboprophylaxis using a risk score for the management of pregnancies with high risk of thrombosis: a prospective clinical study. J Thromb Haemost 15: 897-906.

- Jacobsen AF, Skjeldestad FE, Sandset PM (2008) Incidence and risk patterns of venous thromboembolism in pregnancy and Puerperium –a register-based case control study. Am J Obstet Gynaec 198(2): 233.

- Colman-Brochu S (2004) Deep vein thrombosis in pregnancy. MCN Am J Matern Child Nurs 29: 186-192.

-

Siddig Omer M Handady, Awadalla Mohammed Abdelwahid, Samia Elhaj Elawad Abd Alla, Hajar Suliman Ibrahim Ahmed, Omer Mohamed Ali Mandar. Rate and Risk Profile of Deep Venous Thrombosis in Pregnancy and Postpartum Period Among Sudanese Women. W J Gynecol Women’s Health. 2(5): 2019 WJGWH.MS.ID.000546.

Deep Venous thrombosis, Pregnancy, Postpartum, Rate, Risk profile, Maternal death, Thromboembolism, Post-natal, Postnatal, Cesarean section

-

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.