Research Article

Research Article

Outpatient Hysteroscopy for the Management of Intrauterine Disorders: Feasibility, Effectiveness and Safety For 3000 Cases

Marta Bailón Queiruga MD1, Laura Blanch Fons MD1, Josep Estadella Tarrie MD1,3*, Cristina Vanrell Barbat MD1,3, PhD, Oriol Porta Roda MD, PhD 1,3, Ignasi Gich Saladich MD, PhD 2,3 and Marta Simó González MD, PhD1

1Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Hospital de la Santa Creu i Sant Pau, Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona, Spain

2CIBER Epidemiology and Public Health (CIBERESP), Spain. Department of Clinical Epidemiology and Public Health, Hospital de la Santa Creu i Sant Pau, Universidad Autonoma de Barcelona, Spain

3Biomedical Research Institute Sant Pau (IIB Sant Pau), Spain

Josep Estadella Tarriel MD, Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Hospital de la Santa Creu i Sant Pau, Mas Casanovas 90, 08025 Barcelona, Spain.

Received Date:July 21, 2021; Published Date: August 09, 2021

Summary

Study objective: To assess the feasibility, effectiveness and safety of outpatient hysteroscopies performed in an Office Hysteroscopy Unit.

Design: Retrospective observational study of prospectively collected data in an office hysteroscopy unit database (Canadian Task Force II-2). The study was approved by our hospital’s ethical committee.

Setting: Tertiary care university hospital.

Patients: Included consecutively were 3000 patients who underwent outpatient hysteroscopy between May 2008 and October 2019.

Interventions: Outpatient hysteroscopy was performed using a rigid 5-6 mm diameter device when indicated for diagnostic or therapeutic purposes.

Measurements and Main Results: Feasibility, effectiveness and safety results were evaluated. Outpatient hysteroscopies were successfully performed in 94.5% of cases, with failed hysteroscopies amounting to just 5.5% of cases. Effectiveness was 87.4%, with just 12.6% of women rescheduled for hysteroscopy in a surgical setting. There were no complications in 99% of patients; the main complications otherwise were vasovagal response and uterine perforation (28 and 2 cases, respectively), neither of which required further intervention other than antibiotic treatment and clinical observation.

Conclusion: The results for 3000 outpatient hysteroscopies indicate that office hysteroscopy is a feasible, effective and safe approach to managing most cases of common benign intrauterine disorders. These encouraging results would suggest that outpatient hysteroscopy should be a first line approach to the management of intrauterine conditions.

Keywords: Effectiveness; Feasibility; First line treatment; Office hysteroscopy; Outpatient hysteroscopy; Safety

Introduction

Benign intracavitary intrauterine disorders are common gynaecological conditions. Technical improvements in hysteroscopy instruments, increasingly narrow devices and new kinds of equipment mean that most such disorders can be dealt with using a see-and-treat minimally invasive outpatient approach [1].

The main indications for office hysteroscopy include diagnosis and management of most benign intrauterine disorders, such as abnormal bleeding in premenopausal and postmenopausal women [2,3] focal intrauterine lesions (endometrial polyps or fibroids) [3,4] intrauterine adhesions [5,6] uterine malformations [7,8] retained products of conception [3,9,10] retained intrauterine devices3 and subfertility studies [3].

Outpatient management minimizes patient risk associated with surgery, general anaesthesia and hospitalization [11] especially in women with significant medical comorbidities, while also allowing them to rapidly return to their daily routines [12]. The burden for the healthcare system is also less, bearing in mind costs associated with surgery and hospitalization [13]. Current guidelines recommend that at least 80% and a targeted 90% of diagnostic hysteroscopies should be performed on an outpatient basis [3] suggesting that hysteroscopy in a surgical setting should be reserved only for cases that cannot be successfully managed in an outpatient setting.

Reliable results for outpatient hysteroscopy may help consolidate it as a first line approach to managing most intrauterine disorders [4,11]. The aim of this study was to assess feasibility, effectiveness and safety for 3000 outpatient hysteroscopies performed in our hospital over an 11-year period.

Methodology

Design and sample

This retrospective observational study was based on a prospectively collected database of 3000 consecutive hysteroscopies performed in the 11 years between May 2008 and October 2019 in our Office Hysteroscopy Unit. The study was approved by our hospital’s ethics committee (IIBSP-FES-2019-96) and is registered at Clinical Trials.gov with accession number NCT04462835.

Data for all included patients were prospectively collected in a computerized database. There were no exclusion criteria. The primary endpoint was to measure results in terms of feasibility, effectiveness and safety. Feasibility was defined as the proportion of successfully completed explorations, effectiveness was defined as the percentage of cases that that did not require diagnosis or treatment to be completed in a surgical setting , and safety was defined as the percentage of complications recorded.

We also recorded pain intensity, as perceived by the patient during and 10 minutes after the intervention, using a Verbal Numerical Rating Scale (VNRS), where 0 is no pain and 10 is the worst pain imaginable.

Intervention

Hysteroscopies were performed in the outpatient hysteroscopy box by an experienced gynaecologist assisted by a nurse (Figure 1).

For pain and anxiety management, a painkiller (ibuprofen 600mg) and an anxiolytic (diazepam 5mg) were orally dispensed to patients 30 minutes before the intervention. Cervical preparation, using vaginal misoprostol (400mcg, 4-6 hours before), was performed only in cases of anticipated or previous failed cervical passage. Paracervical anaesthesia was administered in selected cases of severe pain during passage through the cervical canal. Premenopausal women were asked to take, as endometrial preparation, desogestrel 75mg from at least 30 days prior to the intervention. If the patient was unwilling to take desogestrel, the intervention was preferably performed in the early follicular phase.

All hysteroscopies were performed using the vaginoscopy approach. An 0.9% saline solution used as a distension medium was delivered using an automated pressure system (Hysteromat®). The hysteroscopies were performed with, one of the following 5-6mm diameter rigid devices depending on the clinical situation: Minihysteroscope (Olympus)®, scissors, forceps, bipolar electrode (Versapoint®), bipolar Gubbini resector (Colibrí®) or a mechanical morcellator (Myosure® or Truclear®).

Statistical analysis

Categorial variables were expressed as numbers (absolute frequency) and percentages (relative frequency). Quantitative variables were expressed as means ± standard deviation (SD). The chi-square test and the t-test were used to analyses proportions and compare means, respectively. A p-value of 0.05 was considered statistically significant. All descriptive and inferential analyses were performed using IBM-SPSS (V26.0).

Results

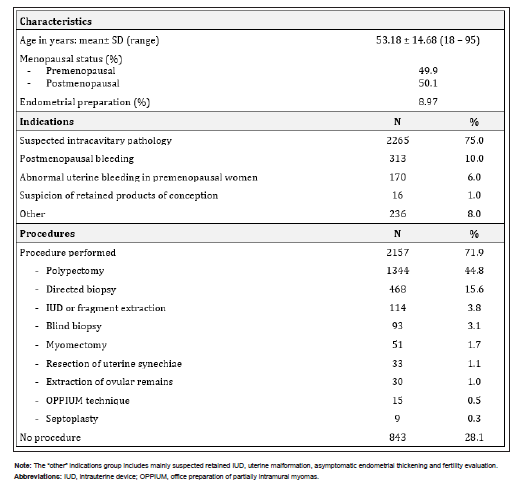

For the 3000 outpatient hysteroscopies performed in our hospital in the 11-year period of study, the main characteristics of the sample, indications and additional procedures are represented in Table 1.

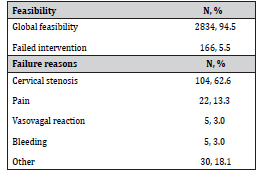

Table 2 shows feasibility rates and reasons for failures, with only 5.5% of procedures (166/3000) failing overall.

Table 1: Patient characteristics, indications and procedures during hysteroscopy.

Table 2: Feasibility and failures.

Regarding effectiveness, 87.4% (n=2621) of the patients required no further surgical intervention, while 12.6% (n=379) were scheduled for surgical hysteroscopy to complete diagnosis or treatment. Finally, regarding safety, complications were recorded in 1% of patients (n=30: 28 vasovagal responses and 2 uterine perforations). The 2 uterine perforation cases required oral antibiotic treatment and no further measures other than observation. No severe bleeding, infections or gas embolism were observed.

Cervical anaesthesia and cervical dilation were required in 5.1% (n=153) and 3.57% (n=107) of the patients, respectively. The mean pain scores during and 10 minutes after the intervention were 5.90 ± 2.67 and 1.38 ± 2.15, respectively (Figure 2).

Pain was greater during and after the intervention when a further procedure was performed (e.g., polypectomy or guided biopsy), for mean scores of 6.12 vs. 5.49 (p<.001) evaluated during the hysteroscopy and 1.59 vs. 0.97 (p<.001) 10 minutes after the procedure.

Discussion

Our findings would suggest that outpatient hysteroscopy is a feasible, effective and safe technique to manage with most benign intrauterine conditions.

Concerning feasibility, our 94.5% rate surpasses the 90% outpatient hysteroscopy recommended in the literature [3] while our failure rate of 5.5% is coherent with the 6%-9.5% rate reported in recent studies [11,14,15].

Our high effectiveness rate (87.4%) meant that just 12.6% of our patients required surgical hysteroscopy. This has benefits for the patient in terms of waiting lists, a simplified intervention, less risk (associated with surgery, general anaesthesia and hospitalization) [11] an early return to routine [12] and a shorter sick leave period. It also reduces the burden on the healthcare system, in terms of direct and indirect costs associated with hospital admission and surgery.

Our complications rate of 1% was similar to the 0.5% reported by Capmas, et al. [15] likewise for a large cohort of cases (n=2402).

One of the main problems of outpatient hysteroscopy may be the pain experienced by patients during the intervention. Most of our patients reported high VNRS scores (mean 5.90 of a maximum of 10) that dropped by 10 minutes after the hysteroscopy. Pain did not represent an impediment to performing most hysteroscopies, however, as only 22 interventions failed due to pain.

Note that a more recent indication for hysteroscopy, whose acceptability is growing, is the removal of retained products of conception. The incidence of intrauterine adherences is significantly reduced by hysteroscopic resection (13%) compared to dilation and curettage (30%) [16]. Hysteroscopy also has the advantage that full evacuation of the uterine cavity can be confirmed visually.

The main strength of this study is the large number of analyzed hysteroscopies, the use of a standard approach and intervention by a limited number of professionals. To our knowledge no such study based on our population has been reported in the literature.

A limitation of the study it that while the data was prospectively collected, the design has to be considered retrospective. Another limitation is that potentially useful information such as parity, previous vaginal delivery, ethnicity and patient satisfaction data were not collected in our database.

Conclusion

Our findings show that outpatient hysteroscopy is a feasible, effective and safe approach to managing the most common cases of benign intrauterine disorders, with clear benefits for both the patient and the healthcare system.

These encouraging results would suggest that outpatient hysteroscopy should be considered as a first line approach to the management of most cases of benign intrauterine disorders.

Acknowledgment

We acknowledge Biomedical Research Institute Sant Pau (IIB Sant Pau) for comments that greatly improved the manuscript.

Conflict of Interest

JET reports conflict of interests from Bayer and Gedeon Richter, outside the submitted work. MBQ, LBF, CVB, OPR, IGS and MSG declare that they have no conflicts of interest and report nothing to disclose.

References

- Kolhe S (2015) Setting up of ambulatory hysteroscopy service. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol 29(7): 966-981.

- (2011) Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (RCOG). Green-top Guideline No. 59: Best Practice in Outpatient Hysteroscopy.

- Cooper NAM, Clark TJ (2013) Ambulatory hysteroscopy. Obstet Gynaecol 15(3): 159-166.

- Bakour SH, Jones SE, O’Donovan P (2006) Ambulatory hysteroscopy: evidence-based guide to diagnosis and therapy. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol 20(6): 953-975.

- (2017) AAGL practice report: practice guidelines on intrauterine adhesions developed in collaboration with the European Society of Gynaecological Endoscopy (ESGE). Gynecol Surg 14(1): 1-11.

- Deans R, Abbott J (2010) Review of Intrauterine Adhesions. J Minim Invasive Gynecol 17(5): 555-569.

- Akhtar MA, Saravelos SH, Li TC, Jayaprakasan K (2020) Reproductive Implications and Management of Congenital Uterine Anomalies. BJOG An Int J Obstet Gynaecol 127(5): e1-e13.

- Grimbizis GF, Camus M, Tarlatzis BC, Bontis JN, Devroey P (2001) Clinical implications of uterine malformations and hysteroscopic treatment results. Hum Reprod Update 7(2): 161-174.

- Capmas P, Lobersztajn A, Duminil L, Barral T, Pourcelot AG, et al. (2019) Operative hysteroscopy for retained products of conception: Efficacy and subsequent fertility. J Gynecol Obstet Hum Reprod 48(3): 151-154.

- Smorgick N, Barel O, Fuchs N, Ben-Ami I, Pansky M, et al. (2014) Hysteroscopic management of retained products of conception: Meta-analysis and literature review. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 173(1): 19-22.

- Mairos J, Di Martino P (2016) Office Hysteroscopy. An operative gold standard technique and an important contribution to Patient Safety. Gynecol Surg 13(2): 111-114.

- Marsh F, Kremer C, Duffy S (2004) Delivering an effective outpatient service in gynaecology. A randomised controlled trial analysing the cost of outpatient versus daycase hysteroscopy. BJOG 111(3): 243-248.

- Bennett A, Lepage C, Thavorn K, Fergusson D, Murnaghan O, et al. (2019) Effectiveness of Outpatient Versus Operating Room Hysteroscopy for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Uterine Conditions: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J Obstet Gynaecol Can 41(7): 930-941.

- Ma T, Readman E, Hicks L, Porter J, Cameron M, et al. (2017) Is outpatient hysteroscopy the new gold standard? Results from an 11 year prospective observational study. Aust New Zeal J Obstet Gynaecol 57(1): 74-80.

- Capmas P, Pourcelot AG, Giral E, Fedida D, Fernandez H (2016) Office hysteroscopy: A report of 2402 cases. J Gynecol Obstet Biol Reprod 45(5): 445-450.

- Hooker AB, Aydin H, Brölmann HAM, Huirne JAF (2016) Long-term complications and reproductive outcome after the management of retained products of conception: A systematic review. Fertil Steril 105(1): 156-164.

-

Marta Bailón Queiruga, Laura Blanch Fons MD, Josep Estadella Tarriel MD, et al. Outpatient Hysteroscopy for the Management of Intrauterine Disorders: Feasibility, Effectiveness and Safety For 3000 Cases. 5(2): 2021. WJGWH.MS.ID.000608.

Effectiveness, Feasibility, First line treatment, Office hysteroscopy, Outpatient hysteroscopy, Safety

-

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.