Research Article

Research Article

Maternal Diabetes Mellitus and Risk of Stillbirth: A Nested Case-Control Study in a Nigerian Tertiary Hospital

Jerome U Ebubechukwu1, Ifeoma B Udigwe2, George U Eleje1,3*, Ekene A Emeka4 and Osita S Umeononihu1

1Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Nnamdi Azikiwe University Teaching Hospital, Nnewi,, Nigeria

2Department of Community Medicine, Faculty of Medicine, Nnamdi Azikiwe University, Nnewi Campus, Nigeria

3Department of Community Medicine, Faculty of Medicine, Nnamdi Azikiwe University, Nnewi Campus, Nigeria

2Department of Family Medicine, Faculty of Medicine, Nnamdi Azikiwe University, Nnewi Campus, Nigeria

George U Eleje, Effective Care Research Unit, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Nnamdi Azikiwe University, Awka (Nnewi Campus), Anambra State, Nigeria.

Received Date: December 05, 2019; Published Date: December 12, 2019

Abstract

Background: Stillbirths have always been a contributor to psychological morbidity amongst women. Diabetes mellitus remains a significant risk factor for its occurrence. Knowledge of the causes and risk factors of this unfortunate problem will help in designing preventive measures to reduce its incidence.

Objective: To determine the relationship between maternal diabetes mellitus and the risk of stillbirths.

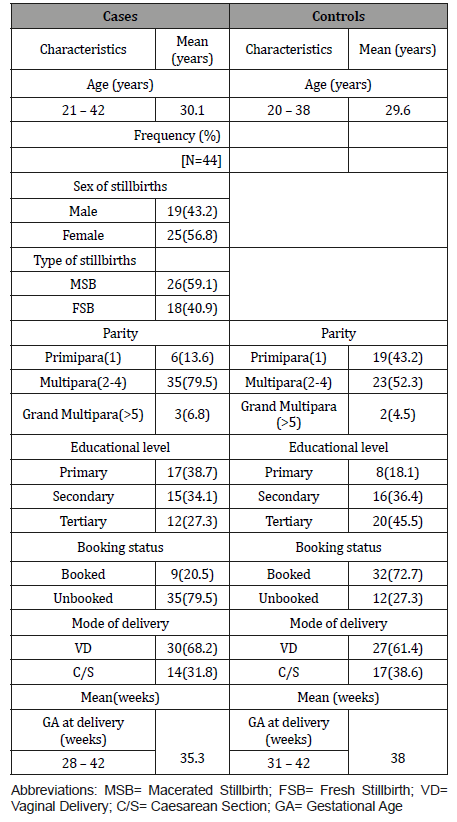

Methods: This is a nested case control study conducted in the Obstetrics unit of the Nnamdi Azikiwe University Teaching Hospital, Nnewi, Nigeria from 1st September 2014 to 31st August 2017. Forty-four women who had stillbirth were regarded as the cases and 44 women who had livebirths were regarded as the control group were retrieved from their case files. Information obtained included; type and sex of the stillborn, maternal age, type of stillbirth, parity, educational status, booking status, gestational age, and mode of delivery. Odds ratio (OR) with 95% confidence interval was calculated to determine the relationship between maternal diabetes and the risk of stillbirth.

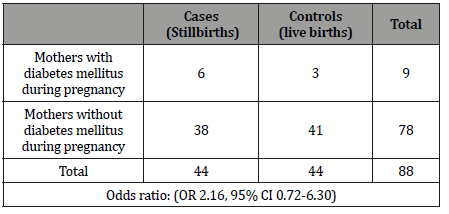

Results: The risk of stillbirth in diabetic pregnancies irrespective of the type was found to be two times higher than in non-diabetic pregnancies (OR 2.16, 95% CI 0.72-6.30). The mean age of the women was found to be approximately 30 years in both cases and controls. The ratio of macerated stillbirth to fresh stillbirth was 1.4:1 and females were affected more than males in a ratio of 1.3:1. The mean gestational age at delivery was 35 weeks for the cases and 38 weeks for the control group. Majority of the women included in the cases had only a primary level of education (34.1%) and never accessed antenatal care services (79.5%) as against the majority of the women in the control group who had a tertiary level of education (45.5%) and were booked for antenatal care (72.7%).

Conclusion: This study established that there is a significant association between maternal diabetes mellitus and stillbirth. The increased occurrence in the cases could be due to ignorance, lack of antenatal care, low socioenomic class and poor control of glycemic levels found among the women. Hence, the need for effective preventive/control programmes for these group of women.

Keywords:Stillbirths, Diabetes mellitus, Pregnancy

Introduction

The World Health Organization (WHO) defined stillbirth as the death of a fetus with a birth weight of at least 500g or if birth weight is unavailable [1,2], a gestational age beyond the age of viability. The stillbirth rate, as the perinatal mortality rate, is an important indicator of the quality of antenatal care and obstetric care during labor and delivery [3]. Knowledge of the causes and risk factors of this unfortunate problem will help in designing preventive measures to reduce its incidence [4]. Stillbirths are common and devastating, and in developed countries, about one-third has been shown to be of unknown or unexplained origin [5]. Some factors have been identified of which few of them have a direct causal relationship such as abruptio placentae, cord accidents, etc., while others may be indirectly related such as preeclampsia, maternal diabetes, maternal smoking, obstructed labor, maternal infections during pregnancy, etc. (all of which are modifiable factors). Stillbirth is classified as fresh stillbirth when the baby is born with an intact skin suggesting that the death occurs during labor (less than 12 hours before delivery), and macerated stillbirth, when there are signs of degeneration (pealing of skin, red serous effusions in the chest and abdomen due to Haemoglobin staining) suggesting that the death occurred more than 12-24 hours before labor [5]. Macerated stillbirths are often associated with insults that occur in utero during the antenatal period.

Diabetes concurrent with pregnancy is a high-risk condition and is associated with an increased risk of perinatal mortality [6-8] especially if poorly controlled. Other complications in the newborn include hypoglycemia, macrosomia, polycythemia, hyperbilirubinemia, respiratory distress syndrome, prematurity, shoulder dystocia, congenital anomalies, etc. [9-12].

Historically, diabetic pregnancies often ended in unexplained stillbirths [7]. Several researches and attempts have been made to identify the exact cause but has not yielded much results [9-12].

Globally, about 4% of all stillbirths remain attributable to diabetes and diabetic pregnancies continue to increase the risk for perinatal mortality [13]. Before the discovery of insulin, a woman with type 1 diabetes had almost no chance of successful delivery of a healthy baby [9]. With the advent of insulin treatment, pregnancy losses continued to be high, predominantly through stillbirths [9]. According to the WHO update, there were 2.6 million stillbirths in 2015 [10,11] accounting for over 7,178 deaths per day [11]. It has been noted that 98% of these deaths occur in the low- and middleincome populations [10]. About 66% of the worldwide stillbirths is contributed by the developing nations like India, Pakistan, Nigeria, China, Democratic Republic of Congo, Ethiopia, Bangladesh, Indonesia, Tanzania, and Afghanistan[1,2].

In this study, the authors hypothesized that there was no relationship between maternal diabetes and stillbirths (if odds ratio is <1). However, there has been extensive research into the effects of diabetes mellitus on pregnancy outcomes, and in particular on the risk of stillbirths [12,14-27] though not much work has been done in Africa and relatively none in Nigeria. This study was aimed at determining the relationship between maternal diabetes mellitus and the risk of stillbirths.

Methods

This research was carried out at the Nnamdi Azikiwe University Teaching Hospital (NAUTH) Nnewi. A nested case-control design was used to determine the relationship between maternal diabetes and the risk of stillbirth. The study population included the cases (all pregnant women who were admitted and delivered stillbirths whether fresh or macerated) and controls (pregnant women who delivered live babies during the same period in the same hospital) of stillbirths that occurred from 1st September, 2014 to 31st August, 2017. Case files of women who carried their pregnancy beyond the age of viability (28 weeks) and delivered were included while case files of women who could not carry their pregnancy up to the age of viability were excluded. The data was gotten from the medical records department. Controls were randomly chosen in a ratio of 1:1 to the cases. Data extracted included the sex of the stillborn, maternal age, type of stillbirth, parity, educational status, booking status, gestational age (GA), glycemic levels. Maternal age and comorbidities were controlled to remove potential confounders. Data was analyzed and the odds ratio (OR) and 95% Confidence interval (95%CI) calculated to check for the statistical significance. This study was approved by the Ethics committee, NAUTH and permission obtained from the Head of Department, Medical Records, NAUTH, Nnewi before the patients’ case files were retrieved. Information obtained were treated with utmost confidentiality.

Results

A total of 88 case files were analyzed during the study. The women (cases and controls) had their ages ranging from 21-42 years, with a mean age of 30.1years and 20-38 age groups with a mean age of 29.6 years respectively. Up to 56.8% of the cases of stillbirths were females, while 43.2% were males giving a ratio of 1.3:1.

A total of 88 case files were analyzed during the study. The women (cases and controls) had their ages ranging from 21-42 years, with a mean age of 30.1years and 20-38 age groups with a mean age of 29.6 years respectively. Up to 56.8% of the cases of stillbirths were females, while 43.2% were males giving a ratio of 1.3:1.

The parity of the women included in the controls were analyzed, with 52.3% being multiparous, 43.2% primiparous and 4.5% grand multiparous. Up to 36.4% of the women had a secondary level of education, 45.5% tertiary level while 18.1% stopped at primary level. A majority of the women were booked (72.7%). Considering the mode of delivery, 61.4% of the women had vaginal delivery while the remainder delivered via caesarean section (38.6%). The mean gestational age at delivery for the controls was 38.0 weeks.

Using a 1:1 matching criterion, 44 of them were the cases and 44 were the controls. The 44 cases were those that met the inclusion criteria and were included in the study. The odds ratio revealed a statistically significant association between diabetes mellitus and the occurrence of stillbirths (OR 2.16, 95% CI 0.72-6.30) (Tables 1&2).

Table 1:Socio-demographic characteristics of the study population.

Table 2:Maternal diabetes mellitus and the risk of stillbirth.

Discussion

This study confirmed a statistically significant relationship between maternal diabetes mellitus and the risk of stillbirths (OR 2.16, 95% CI 0.72-6.30). This means that women with diabetes mellitus during pregnancy were two times more likely to have a stillbirth when compared to the general population which agreed with a similar study done in different parts of the world by Tennant, et al., Stringer, et al., Hogue et al., and Schmidt, et al. [18,20,24,26].

This study confirmed a statistically significant relationship between maternal diabetes mellitus and the risk of stillbirths (OR 2.16, 95% CI 0.72-6.30). This means that women with diabetes mellitus during pregnancy were two times more likely to have a stillbirth when compared to the general population which agreed with a similar study done in different parts of the world by Tennant, et al., Stringer, et al., Hogue et al., and Schmidt, et al. [18,20,24,26].

This study reported a ratio of 1.4:1 between MSB and FSB. There was a slight increased rate of affectation of the females when compared to the males in a ratio of 1.3:1 which disagreed with a similar study conducted by Petridon, et al. and Alrahmman and Alaf who found higher mortality rate among male fetuses [28,30]. On comparison of the booking status of the cases (booked 20.5%, unbooked 79.5%) and controls (booked 72.7%, unbooked 27.3%), it was found that women who booked for antenatal care during pregnancy had a significantly decreased risk of having stillbirths due to proper monitoring of the progress of pregnancy during the antenatal period which included good glycemic control in those of them who had diabetes mellitus. This correlated with a similar study done by Alrahmman and Alaf, Agudelo, et al. and Feresus, et al. [28-31].

Majority of the women who had stillbirths had vaginal delivery, 65.9%, while the rest delivered via caesarean section, 31.8%. This agreed with a similar study done in Erbil Teaching Hospital, Kurdistan region, Iraq [28]. On analysis of the mean gestational age in both cases (35.3weeks) and controls (38.0weeks), it was also found that mothers included in the cases delivered pre-term (<37 completed weeks). Also, noted in the pregnancy outcomes in women who had diabetes mellitus included omphalocoele, fetal macrosomia, congenital hip dislocation in some of the babies delivered and polyhydramions in their mothers during pregnancy.

The major strength of this study is the nested case-control of its design. It appears to be the first case-control study in the study center on the potential relationships between diabetes mellitus and still birth rates. The major limitations were that some data were missed due to the fact that data were retrospectively extracted in the case files. Further study will require a prospective design.

Conclusion

This study established that there is a significant association between maternal diabetes mellitus and stillbirth. The increased occurrence in the cases could be due to ignorance, lack of antenatal care, low socioenomic class and poor control of glycemic levels found among the women. Hence, the need for effective preventive/ control programmes for these group of women. There is also the need for adequate and close monitoring of the glycemic levels of those diabetic prior to conception or at risk of developing diabetes mellitus during pregnancy. Also, monitoring of the fetal kick counts and symphysio-fundal height measurement are very essential and would help detect the early signs of hypoxia in the fetus.

Authors Contribution

JUE and IBU contributed to the study conceptualization and methodology; JUE conducted the clinic study, ensured completion of the participants data and extracted the required data; JUE and GUE analysed the data and drafted the original manuscript; EAE and OSU worked with JUE on formal analysis; IBU, GUE, EOU, EAE and OSU contributed to the project administration, writing (review and editing), data visualization, and supervision. All authors have seen and approved their contributions and the final version of the manuscript.

Acknowledgement

The authors wished to thank the staff in the hospital that participated in the management of the women who had participated in this study.

Conflict of Interest

Authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Joseph KS, Basso M, Davies C, Lee L, Ellwood D, et al. Rationale and recommendations for improving definitions, registration requirements and procedures related to fetal death and stillbirth. BJOG 124(8): 1153-1157.

- Froen JF, Gordigin, SJ, Abdel-Aleem H, Bergsjo P, Betran A, et al. (2009) Making stillbirths count, making numbers talk – issues in data collection for stillbirths. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 9: 58.

- Kambarani RA (2002) Levels and risk factors for mortality in infants with birth weights between 500grams and 1,800grams in a developing country: a hospital based study. Cent Afr J Med 48(11-12): 133-136.

- Kuti O, Owolabi AT, Orji EO, Ogunloba IO (2003) Antepartum fetal death in a Nigerian Teaching Hospital: Etiology and risk factors. Trop J Obstet Gynaecol 20(2): 134-136.

- (2006) Neonatal and Perinatal Mortality: Country, Regional, and Global Estimates. World Health Organization; Geneva, Switzerland.

- Feresus SA, Harlow SD, Welch K, Gillespie BW (2005) Incidence of stillbirth and perinatal mortality and their associated factors among women delivering at Harare maternity hospital, Zimbabwe: a cross-sectional retrospective analysis. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 5(1): 9.

- Saxena P, Gaur J (2017) Unravelling the Mystery of Perinatal Deaths in Diabetic Pregnancy. Curre Res Diabetes & Obes J 4(2): 555633.

- Chakrabarti S, Chowdhury S, Ghosh S, Guha M, Ghosh S, et al. (2015) Stillbirth and Miscarriage Associated with Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus. Int J Res Dev PharmLSci 4: 1732-1736.

- (2016) World Health Organization. Fact Sheet: Still Births.

- Lakshmi ST, Thankam U, Jagadhamma P, Ushakumari A, Chellamma N, et al. (2017) Risk factors for stillbirth: a hospital based case-control study. Int J Reprod Contracept Obstet Gynecol 6(3):970-974.

- Rezai S, Cokes CW, Gottimukkala S, Penas RP, Chadee A, et al. (2016) Review of Stillbirths among Antepartum Women with Gestational and Pre- Gestational Diabetes. Obstet Gynecol Int J 4(4): 00118.

- Stankov R, Dudley D, Reddy UM (2015) Stillbirths in pregnancy complicated by diabetes. Curr Diab Rep 15(3): 11.

- NCD Risk Factor Collaboration (NCD-RisC) (2016) Worldwide trends in diabetes since 1980: a pooled analysis of 751 population-based studies with 4.4 million participants. Lancet 387(10027): 1513-1530.

- (2017) WHO| Stillbirths.

- (2013) Gestational diabetes mellitus Practice Bulletin No. 137. American College of Obstetrics and Gynecology. Obstet Gynaecol 122: 406-416.

- Walsh N (2017) Fetal Death Rates High in Diabetic Women. MedPage.

- dos Santos Silva I, Higgins C, Swerdlow AJ (2005) Birth weight and other pregnancy outcomes in a cohort of women with pregestational insulin treated diabetes mellitus, Scotland, 1979-95. Diabet Med 22(4): 440-447.

- Tennant PW, Glinianaia SV, Bilous RW, Rankin J, Bell R (2014) Pre-existing diabetes, maternal glycated Haemoglobin, and the risks of fetal and infant death: a population-based study. Diabetologia 57(2): 285-294.

- Casson IF, Clarke CA, Howard CV (1997) Outcomes in pregnancy in insulin dependent diabetic women: results of a five-year population cohort study. BMJ 315(7103): 275-278.

- Schmidt MI, Duncan BB, Reichelt AJ (2001) Gestational diabetes mellitus diagnosed with 2-hour 75gm oral glucose tolerance test and adverse pregnancy outcomes. Diabetes Care 24(7): 1151-1153.

- Mondestein MA, Ananth CV, Smulian JC (2002) Birth weight and fetal death in the United States: the effect of maternal diabetes during pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol 187(4): 922-926.

- Hutcheon JA, Kuret V, Joseph KS, Sabr Y, Lim K (2013) Immortal time bias in the study of stillbirth risk factors: the example of gestational diabetes. Epidemiology 24(6): 787-790.

- Ibiebele I, Coory M, Smith GC, Boyle FM, Vlack S, et al. (2016) Gestational age specific stillbirth risk among Indigenous and non-Indigenous women in Queensland, Australia: a population based study. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth 16: 159.

- Stringer EM, Vwalika B, Killiam WP, Giganti MJ, Mbewe R, et al. (2011) Determinants of stillbirths in Zambia. Obstet Gynaecol 117(5): 1151-1159.

- Tofelac NP, Tamambang RG, Egbe TO (2017) Ten years analysis of stillbirths in a tertiary hospital in sub-Saharan Africa: A case control study. BMC Res Notes 10(1): 447.

- Hogue JC, Parker CB, Willinger M, Temple JR, Bann CM, et al. (2013) A population-based case control study of stillbirth: The relationship of significant life events to the racial disparity for African Americans. Am J Epidemiol 177(8): 755-767.

- Di Mario S, Say L, Lincetto O (2007) Risk of stillbirth in developing countries: a systematic review. Sex Transm Dis 34(7 Suppl): S11-S21.

- Alrahmman SA, Alaf, SK (2015) Incidence and probable risk factors of stillbirth in Maternity Teaching Hospital in Erbil city. Zanco J Med Sci 19(3): 1057-1062.

- Agudelo AC, Belizán JM, Rossello JL (2000) Epidemiology of fetal death in Latin America. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 79(5): 371-378.

- Petridon E, Kotsifakis G, Revinthi K, Polychronopoulou A, Trichopoulos D (1996) Determinants of stillbirth mortality in Greece. Soz Praventivmed 41(2): 70-78.

- Lyon JL, Sara M, Alder SC, Varner MW (2005) Effects of grand multipara on intrapartum and newborn complications in young women. Obstet Gynecol 106(3): 454-460.

-

Jerome U Ebubechukwu, Ifeoma B Udigwe, George U Eleje, Ekene A Emeka, Osita S Umeononihu. Maternal Diabetes Mellitus and Risk of Stillbirth: A Nested Case-Control Study in a Nigerian Tertiary Hospital. W J Gynecol Women’s Health. 3(2): 2019. WJGWH.MS.ID.000556.

Stillbirths, Diabetes mellitus, Pregnancy, Glycemic levels, Placentae, Haemoglobin staining, Prematurity, Shoulder dystocia

-

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.