Research Article

Research Article

Incidence of Post-Partum Depression among Female Patients Presenting in the Outpatient Clinic of Obstetrics & Gynecology Department in ACTH At Khartoum State, September - November 2017

Aiya A Siddig1, Ibrahim A Ali2*, Wala M Elfatih Mahgoub3 , Mohamed R Mohamed1 and Ahmed M Eltohami4

1Faculty of Medicine, University of Medical Science and Technology, Sudan

2Department of Physiology, Faculty of Medicine, The National Ribat University, Sudan

3Department of Anatomy, Faculty of Medicine, The National Ribat University, Sudan

4Department of Medicine, Faculty of Medicine, University of Khartoum, Sudan

Ibrahim Abdelrhim Ali, Assistant Professor of Medical Physiology, Department of Physiology, Faculty of Medicine, The National Ribat University, Sudan

Received Date: June 26, 2020; Published Date: July 10, 2020

Abstract

Purpose: To determine the incidence of post-partum depression among female patients as this form of mental illness is much more serious than the “baby blues” (relatively mild depressive and anxiety symptoms that typically clear within two weeks after delivery) that many women experience after giving birth. Women with PPD may experience full-blown major depression during pregnancy or after delivery. The feelings of extreme sadness, anxiety, and exhaustion that accompany PPD may make it difficult for these new mothers to complete daily care activities for themselves and/or for their newborns. Early diagnosis and management are essential for the prevention of serious complications.

Materials and methods: This is a descriptive analytical hospital-based prospective study. Study included a total coverage of all women attending the outpatient clinic of Obstetrics and gynecology 4-6 weeks post-partum, which was a total of 40 women. Each woman answered the questionnaire in an interview method and the score of the Edinburgh Post Natal Depression Scale (EPDS) was recorded along with the factors included in the “added” questionnaire; marital status, partner support, employment and socioeconomic status. As for the EPDS scoring, any score of 10 or higher is considered suggestive of PPD.

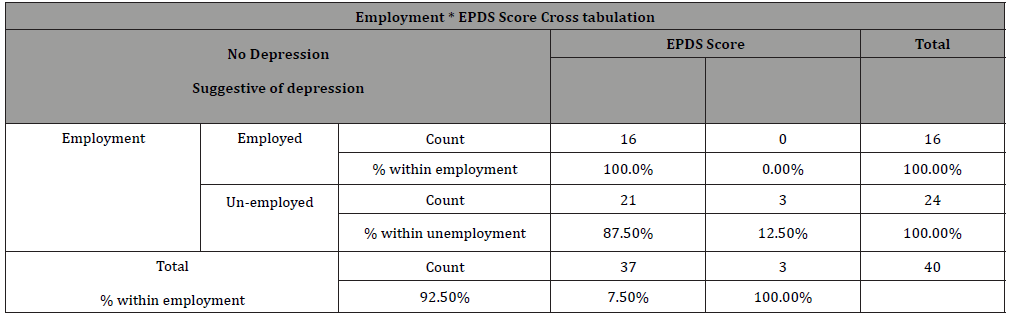

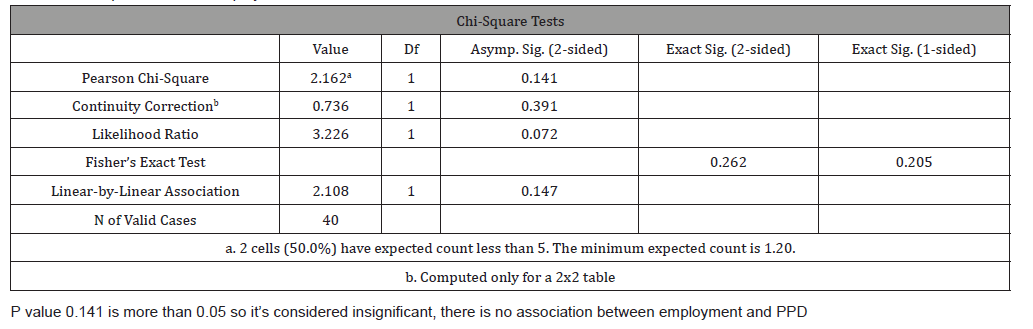

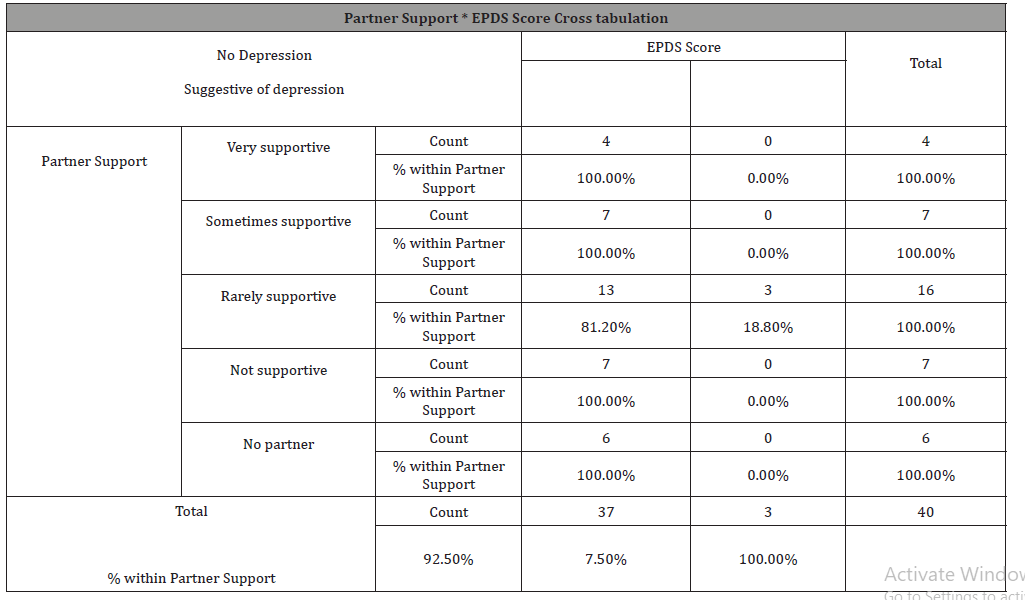

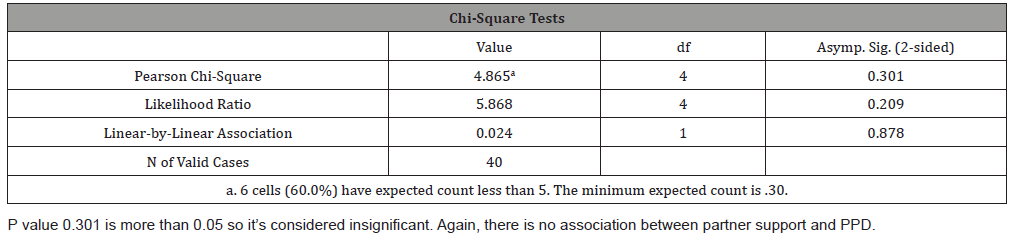

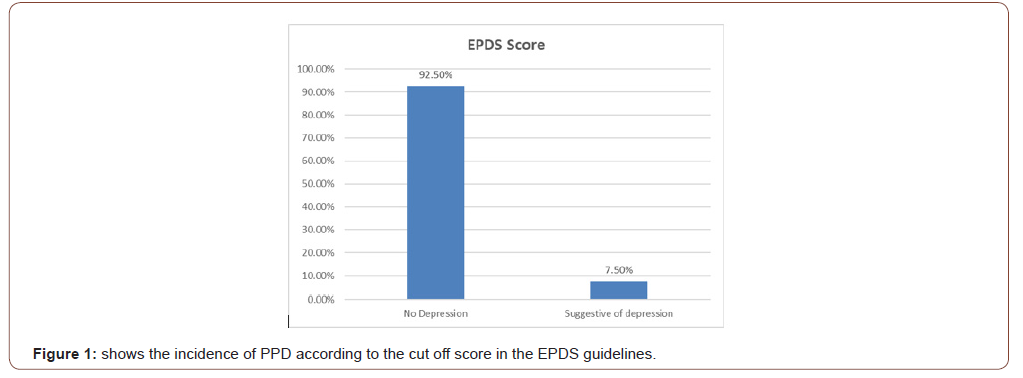

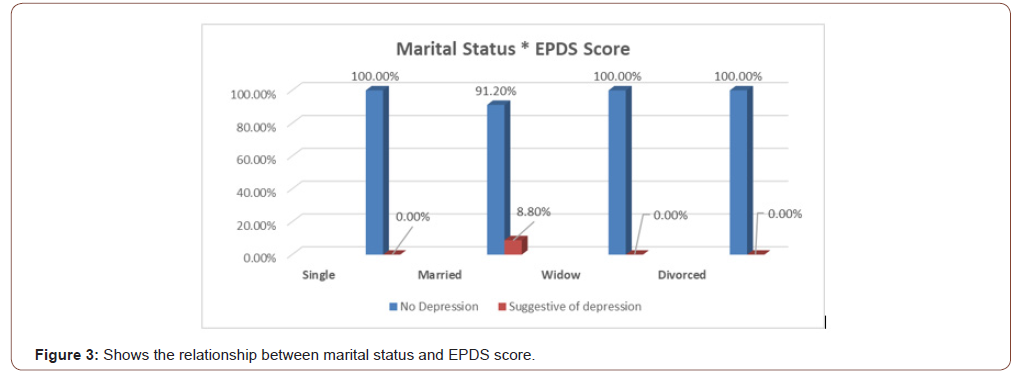

Results: The incidence of PPD among the taken sample was found to be was found to be 7.5% - only three women presented with a score of equal/more than 10. With regards to marital status; single, widowed and divorced women all had EPDS scores less than 10; so, no depression. Of married women, 8.8% had EPDS scores of equal to or greater than 10 suggesting PPD. However, the p value for the association between marital status and PPD was (0.903) which is considered insignificant. Significant EPDS scores for depression were also shown to present with women complaining of “rarely supportive” partners, as all three women presenting with PPD were in that category. The p value for this association was found to be (0.301), also insignificant. When it comes to socioeconomic status, all three women with PPD were of low socioeconomic status, that is 8.6% of all those with low socioeconomic status presented with EPDS scores of 10 or higher. The p value for this association was found to be (0.496), insignificant. 12.5% of women who are unemployed presented with PPD while all those employed had no significant EPDS scores. The p value for this association was (0.141) which is, once again, insignificant.

Conclusion: According to the results obtained, the incidence of PPD is 7.5% and it appears that there is no significant association between PPD and any of the factors mentioned; marital status, employment, partner support and socioeconomic status. All P values were greater than 0.05.

Keywords: Post-partum depression; Edinburgh postnatal depression scale

Abbreviations: ACTH: Academy Charity Teaching Hospital; EPDS: Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale; PPD: Post-Partum Depression

Introduction

Post-Partum Depression (PPD), also known as Post Natal Depression is a form of depression and/or anxiety that presents after childbirth. It usually presents about 4-6 weeks after delivery and may last up to a few years if left untreated. Patients with this mood disorder can present with low mood, irritability, feelings of anxiousness, low levels of energy, changes in sleeping and eating patterns, feelings of guilt and crying episodes. Patients may even present with suicidal thoughts. As with Major Depressive Disorder (MDD), these symptoms must be present for two consecutive weeks to confirm the diagnosis of PPD. This condition can affect both sexes, the father of the newborn may experience these symptoms too, but in this research, I will be focusing on the new mothers rather than their partners. In the past, many risk factors for PPD have been studied. The emphasis has historically been on psychosocial aspects, such as a personal history of psychiatric illness (previous PPD being a highly significant risk factor) [1] low socioeconomic status, low level of education, alcohol and drug abuse, and low levels of social or partner support [2,3].

After pregnancy, hormonal changes in a woman’s body may trigger symptoms of depression. During pregnancy, the amount of two female hormones, estrogen and progesterone, in a woman’s body increases greatly. In the first 24 hours after childbirth, the amount of these hormones rapidly drops back down to their normal non-pregnant levels. Researchers think the fast change in hormone levels may lead to depression, just as smaller changes in hormones can affect a woman’s moods before she gets her menstrual period.

Not surprisingly, women with fewer resources indicate a higher level of postpartum depression and stress than those women with more resources, such as financial. Rates of PPD have been shown to decrease as income increases [4]. Women with fewer resources may be more likely to have an unintended or unwanted pregnancy; increasing risk of PPD. Women with fewer resources may also include single mothers of low income. Single mothers of low income may have more limited access to resources while transitioning into motherhood.

Occasionally, levels of thyroid hormones may also drop after giving birth. Low thyroid levels can cause symptoms of depression including depressed mood, decreased interest in things, irritability, fatigue, difficulty concentrating, sleep problems, and weight gain. A simple blood test can tell if this condition is causing a woman’s depression. If so, thyroid medicine can be prescribed.

Once diagnosed, PPD is treated just like any other MDD through “Biopsychosocial” care which consists of anti-depressants/ hormone replacement if needed, appropriate psychotherapy and social support. However, making the diagnosis is not easy as most mothers do not seek help or pay attention to their symptoms; it’s usually ignored and assumed to just be a phase that will go away on its own. That is why the EPDS is a very important screening tool that helps many women face their problems and seek the appropriate care that they need for themselves and subsequently for their children.

A 2013 Cochrane review found evidence that psychosocial or psychological intervention after childbirth helped reduce the risk of postnatal depression [5,6]. These interventions included home visits, telephone-based peer support, and interpersonal psychotherapy [5] Support is an important aspect of prevention, as depressed mothers commonly state that their feelings of depression were brought on by “lack of support” and “feeling isolated” [7].

In couples, according to a systematic review and meta-analysis of 2015, emotional closeness and global support by the partner protect against both perinatal depression and anxiety. Further factors such as communication between the couple and relationship satisfaction have a protective effect against anxiety alone [8].

A major part of prevention is being informed about the risk factors. The medical community can play a key role in identifying and treating postpartum depression. Women should be screened by their physician to determine their risk for acquiring postpartum depression. Also, proper exercise and nutrition appear to play a role in preventing postpartum depression and depressed mood in general.

Materials and Methods

Descriptive Analytical hospital-based prospective study was conducted in Academy Charity Teaching Hospital (ACTH). The sample obtained was representative of the total coverage during September- November 2017, which equated to 40 cases. Data was collected through an interview-based questionnaire (an Arabic translated version of Edinburgh Post Natal Depression Scale).

Data analysis

Data was processed and analyzed using the Statistical Package of Social Sciences (SPSS version 20). Chi square test and independent T test were used to study the significance and associations of variables in the study. Data will be presented in forms of tables and charts for this study.

Ethical approval

Ethical clearance was obtained from the research technical and ethical committee at the faculty of Medicine in UMST and ACTH administration.

Verbal consent was taken from all patients participating in the study. The process was clearly explained to each patient. They were assured about their safety and confidentiality and that there was no harm in responding.

Results

EPDS considered those who score equal to or more than 10 are positive for symptoms of PPD, and regarding this study 40 of women who interviewed only 3 had scored 10 or higher, making the incidence of PPD among the study group equaling approximately 7.5% (Figure 1).

Table 1: Shows the relationship between employment and EPDS scores suggestive of PPD.

Table 2: Chi square Tests for employment status vs. PPD.

Table 3: Chi square tests for socioeconomic status vs. EPDS score indicating PPD.

Table 4: Chi Square Tests of Marital Status vs. EPDS score indicating PPD.

Table 5: Shows association between Partner Support and EPDS score indicating PPD.

Table 6: Chi square tests for partner support vs PPD

Out of 24 unemployed women, 3 had positive symptoms of PPD (12.5%) while out of 16 employed women, none had positive symptoms (0%) (Table 1), but despite this fact which comprehended in this study the chi- square test showed there is no significant association between employment and PPD as p-value was greater than 0.05 (Table 2). Those of low socioeconomic status appear to have a higher incidence of depressive symptoms (8.6%) as oppose to those of moderate socioeconomic class who have no significant symptoms (Figure 2), and also there is no association between socioeconomic status and PPD ( Table 3). Women showing signs of depression(8.8%) were all married, with 0% depressed among single, widowed and divorced women (Figure 3), and there is no association between marital status and PPD (Table 4). In terms of ‘’partner support’’ the study showed that 3 women with “rarely supportive partners” have shown signs of depression (18.8%), while those with ‘’supportive, sometimes supportive, not supportive partners and those with no partners at all’’ show 0% of PPD (Table 5), and again there is no association between ‘’partner support’’ and PPD (Table 6).

Discussion

This study revealed some expected and some greatly unexpected points when it came to the results obtained. Firstly, the incidence of women suffering from postpartum depression wasn’t very high, only 7.5% (3 out of 40 women) had positive symptoms of Post- Partum Depression. This result is comparable to another study that conducted in Mexico by Lara M, et al. [9] which found the incidence of PPD at six weeks to be 10% and to another one that conducted in India by Chandran M, et al. [10] in which the incidence was 11%.

These three women were all unemployed, poor, married women with a “rarely supportive” husband. 12.5% of unemployed women (that is 3 out of 24 unemployed women), 18.8% of women with “rarely supportive” husbands, 8.8% of married women and 8.6% of women of low socioeconomic status presented with symptoms of Post-Partum Depression and scored 10 or more on the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS).

Using Chi square testing, P values of all these associations were greater than 0.05. So, as it appears there is no significant association between these factors and Post-Partum Depression although these factors were proven in other researches to be significant. Such as Qatar’s prospective cross-sectional study , done by Bener A, et al. [11] which concluded that financial difficulties and poor marital relationships were major risk factors for developing Post-Partum Depression.

Conclusion

The incidence of Post-Partum Depression, using EPDS was found to be 7.5% which is comparable to findings in other developing countries. However; marital status, employment, partner support and socioeconomic status not significant associations with the incidence of PPD.

Acknowledgement

None.

Conflict of Interest

Authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Josefsson A, Sydsjö G (2007) A follow-up study of Postpartum depressed women: recurrent maternal depressive symptoms and child behavior after four years. Arch Womens Ment Health 10(4): 141-145.

- Milgrom J, Gemmill AW, Bilszta JL, Hayes B, Barnett B, et al. (2008) Antenatal risk factors for Postnatal depression: a large prospective study. J Affect Disord 108(1-2): 147-157.

- O’Hara MW (2009) Postpartum depression: what we know. J Clin Psychol 65(12): 1258-1269.

- Segre LS.; O'Hara MW, Losch ME (2006) Race/ethnicity and perinatal depressed mood. Journal of Reproductive and Infant Psychology 24(2): 99-106.

- Dennis CL, Dowswell T (2013) Psychosocial and psychological interventions for preventing postpartum depression. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2: CD001134.

- (2013) PubMed Health Preventing postnatal depression. National Center for Biotechnology Information.

- Dennis CL, Hodnett E, Kenton L, Weston J, Zupancic J, et al. (2009) Effect of peer support on prevention of postnatal depression among high risk women: multisite randomised controlled trial. BMJ 338: a3064.

- Pilkington PD, Milne LC, Cairns KE, Lewis J, Whelan TA (2015) Modifiable partner factors associated with perinatal depression and anxiety: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Affect Disord 178: 165-180.

- Lara MA, Navarrete L, Nieto L, Barba Martín J, Navarro J, et al. (2015) Prevalence and incidence of perinatal depression and depressive symptoms among Mexican women. J Affect Disord 175: 18-24.

- Chandran M, Tharyan P, Muliyil J, Abraham S (2002) Post-partum depression in a cohort of women from a rural area of Tamil Nadu, India: Incidence and risk factors. Br J Psychiatry 181(6): 499-504.

- Bener A, Burgut FT, Ghuloum S, Sheikh J (2012) A Study of Postpartum Depression in a Fast Developing Country: Prevalence and Related Factors. Int J Psychiatry Med 43(4): 325-337.

-

Aiya A Siddig, Ibrahim A Ali, Wala M Elfatih Mahgoub. Incidence of Post-Partum Depression among Female Patients Presenting in the Outpatient Clinic of Obstetrics & Gynecology Department in ACTH At Khartoum State, September - November 2017. W J Gynecol Women’s Health. 4(2): 2020. WJGWH.MS.ID.000584.

Giant teratoma, Pelvic mass, Laparotomy, Computed tomography, Epithelial tumors, Ovarian tumors, Carcinoembryonic antigen

-

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.