Research Article

Research Article

COVID-19 Pandemic; Impact on the Colposcopy Service

Aisha Bojang1, Lina Antoun1, Orestis Tsonis2 and Fani Gkrozou1*

11Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, University Hospitals of Birmingham, NHS Foundation Trust, UK

22Department of Reproductive Medicine, St. Bartholomew’s Hospital, Barts Health NHS, UK

Fani Gkrozou, Consultant in Obstetrics and Gynaecology, University Hospitals of Birmingham, NHS Foundation Trust, Bordesley Green E, Birmingham B9 5SS, UK.

Received Date:September 02, 2021; Published Date: September 22, 2021

Summary

Objectives: The COVID-19 pandemic caused by SARS-CoV-2 has radically changed global healthcare and colposcopy services are no exception. The aim of this study was to review the effect of COVID-19 pandemic on colposcopy services in a tertiary center.

Study design: A retrospective observational study was conducted in a tertiary center between March to August 2020. We included all women referred to our colposcopy services. The practice has been reviewed according to guidance from BSCCP.

Results: For high grade dyskaryosis referral, 64% of patients were offered an appointment within the target 2 week-wait time frame. For low grade dyskaryosis referral, 47% of patients were seen within the target 12-week timeframe.

Conclusions: The COVID-19 pandemic has resulted in longer waiting times for both high- and low-grade colposcopy referrals. This highlights the need for better preparation for potential future disruption of services and improvement of the existing service provided in order to support a faster and more efficient recovery from the pandemic.

Keywords: Colposcopy service; Covid 19 pandemic; Service provision

Introduction

In March 2020, the World Health Organization (WHO) declared the novel coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) as a pandemic [1]. In the space of a few months after the start of the pandemic crisis, profound organizational changes have been adopted worldwide to optimize the healthcare facilities resources utilization.

Cervical cancer is the only one of the five gynaecological cancers to have an effective screening programme, however, during the COVID-19 pandemic, some of the 2 weeks wait cancer referrals were delayed or avoided when hospital’s capacity was particularly constrained, which affected cervical cancer prevention and management, including Human Papilloma Virus (HPV) vaccination, screening programme, colposcopy, and outpatient surgery.

A guidance by British Society for Colposcopy and Cervical Pathology [2] was put in place to triage patients who needed prompt evaluation in a colposcopy clinic including patients who had a high-grade smear, borderline nuclear change in endocervical cells, glandular neoplasia or suspicion of invasive disease [2]. Virtual consultations were advised for low grade referrals and for these patients to only be seen if resources permitted and to be deferred if colposcopy clinic capacity were reduced [2].

The aim of this study is to review the effect of the COVID-19 pandemic on colposcopy services in a tertiary center. We evaluated the process of patient selection in this tertiary unit’s colposcopy services during the pandemic benchmarked with Trust’s policy during the first wave of the pandemic and BSCCP guidelines. Our study will help understand the effect of such pandemic on our cervical cancer referral pathways to help plan our services in the future, especially should this pandemic result in a third wave of cases [3].

Materials and Methods

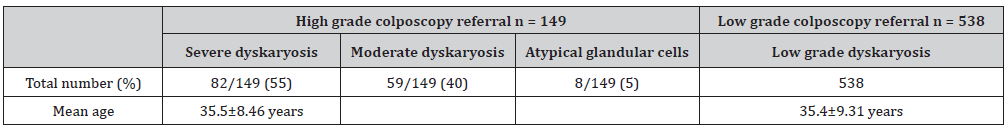

The colposcopy cases were undertaken at a United Kingdom (UK) teaching hospital trust, University Hospitals Birmingham NHS Foundation Trust, where colposcopy service runs at three hospital sites (Heartlands, Good Hope and Solihull Hospitals) from March 2020 to August 2020, during the first wave of the pandemic. That period, it was decided by Trust to offer appointments only to women with high grade cytology after smear test and with urgent referral from General Practitioner (GP). Results are presented for 151 patients referred with high grade dyskaryosis (group A) and 538 women with low grade cytology results (group B), from March 2020 to August 2020. Mean patient age at referral was 35.5±8.46 years, ranged (25-71) for group A and 35.4±9.31 years, ranged 24 to 66 years for group B.

Retrospective observational study on data from a populationbased cervical cancer screening database. This is the national database which is used to each colposcopy department in the UK and is provided by NHS England. For each patient information gathered regarding age, reason of referral/ smear result, histology result and treatment, when necessary, based on the information from colposcopy database. Steps in the screening process being disrupted (primary screening, surveillance, colposcopy, excisional treatment) were documented.

Baseline histology testing and delay in diagnosis were reported in patients referred for colposcopy. Categorical variables were presented as frequencies and percentages. It has to be mentioned that before the pandemic, our service was able to follow the national guidelines and keep the targets recommended by NHS England without any delays.

Precautions undertaken during COVID-19

Precautions undertaken for diagnostic and operative colposcopy were reviewed in line with Trust’s guidance and BSCCP guidelines including appropriate personal protective equipment (gloves, apron and appropriate mask) and minimum staff presence during procedures (BSCCP, 2020). BSCCP advised the avoidance of laser ablation and excision as well as use of coagulation procedures with diathermy due to vaporization [2]. For any large loop excision of transformation zone (LLETZ) procedure, the use of a serviced smoke extractor was advised [2]. For patients with symptoms suggestive of COVID-19 infection, colposcopy assessment was delayed until symptoms resolved, or patient tested negative. In accordance with our Trust’s policy, the number of women seen in colposcopy clinic had to be reduced by 5 for each clinic, to avoid unnecessary contact in waiting area. In addition, waiting area had to be reformed, to keep the rules for distance of two meters.

Results

High grade dyskaryosis colposcopy referrals

In total we had 151 patients referred with high grade dyskaryosis during this time period, out of which 149/151 (99%) attended. The commonest index cytology for referral was severe dyskaryosis 82/149 patients (55%) followed by moderate dyskaryosis 59/149 patients (40%). Three patients were referred directly due to suspected malignancy from cytology. Eight more patients were referred urgently with glandular cytology or post coital bleeding with known previous borderline cytology (Table 1).

Table 1: Referrals according to cytology results.

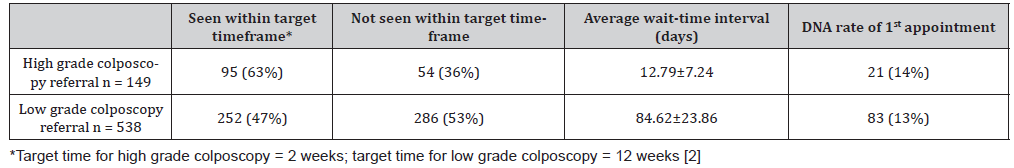

Of the total high-grade patients that were referred to colposcopy services, 95/149 patients (64%) were offered an appointment within the two weeks wait timeframe, and 54/149 patients (36%) were offered an appointment outside the two weeks’ timeframe. The average time from referral to 1st appointment being offered was 12.79±7.24 days (Table 2). This wait-time interval ranged from 1 to 35 days. All first-time appointments offered were face-to-face appointments.

Table 2: Wait time intervals.

Furthermore, we had 128/149 (86%) patients attending their first appointment compared to 21/149 (14%) of patients failing to attend. All patients that failed to attend their initial appointment were re-offered a second appointment date. Out of the 21 patients who did not attend their initial appointment date, 9/21 patients (43%) attended the second appointment date offered. 8/21 patients (38%) attended on their third appointment date offer. 4/21 patients (19%) were discharged back to their GP after failing to attend their second appointment date that was offered. On colposcopy database the reason of patient’s nonattendance was not documented.

Overall, 4/149 patients (3%) did not attend at all and were discharged back to their GP. All 149 patients who attended their appointments had a biopsy taken. The commonest histological finding was CIN 3 which was 67/149 patients (45%) followed by CIN 2, 29/149 patients (20%). Furthermore, we had 12/149 (8%) reported as CIN 1, and 41/149 (28%) were reported as cervicitis due to HPV changes or normal.

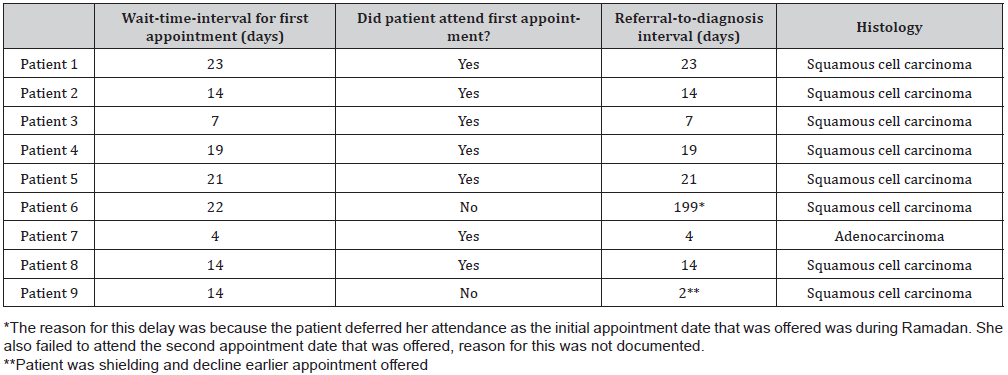

Out of the 149 patients with high grade cytology referrals, 9/149 patients (6%) were diagnosed with cancer. Five of these were offered an initial appointment within 2 weeks of referral and 4 patients had their first appointment date after 2 weeks of referral. Two patients failed to attend the first initial appointment that was offered. The average time from referral to patient being seen for these 9 patients was 35.8 days (Table 3).

Table 3: Patients diagnosed with cervical cancer and wait time intervals.

Low grade dyskaryosis colposcopy referrals

There were 539 referrals with low grade dyskaryosis during this time. One patient was excluded as the patient opted to be seen privately before appointment.

Out of the total patients who were referred due to low grade dyskaryosis, 252/538 of patients (47%) were offered an appointment within 12 weeks, as per BSCCP recommendation for management of low grade dyskaryosis during COVID-19 pandemic first wave (2), whilst 286/538 patients (53%) were offered an appointment after 12 weeks of referral in view of the prioritization of referrals during the COVID-19 pandemic depending on the smear result. The average wait-time interval for low grade patients was 84.62±23.86 days and ranged from 3 to 224 days (Table 2). In our study, 447/538 patients (83%) attended their initial appointments, whilst 83/538 patients (15%) did not attend this appointment. Information on appointment date could not be found for 8 patients due to incomplete data input.

Out of the 447 patients seen, 145/447 (32%) had a biopsy for further analysis, whilst 302/447 (68%) were discharged. The most common histological finding was CIN 1 in 40/145 patients (28%), followed by viral changes due to HPV effect in 36/145 patients (25%). Furthermore, 69/447 (15%) had normal biopsy result. No patients in this referral group had cancer and all firsttime appointments offered were face-to-face appointments for colposcopy.

From the retrospective analysis of this sample, we were in the position to identify that all the necessary precautions were taken according to the BSCCP recommendations at the time that the guidance was published. The time for each appointment increased from 20 to 40 minutes, to provide extra time for the relevant PPE and at the same time to prevent women being in contact in the waiting area.

Discussion

This study shows a delay in offering an appointment in time for low- and high-grade cytology referrals. Nine patients had a diagnosis of cancer and 5 of these patients had a delay in diagnosis (i.e., referral-to-diagnosis interval of > 2 weeks). This delay in diagnosis would inevitably lead to a delay in treatment and subsequently impact on morbidity and mortality, but it is necessary to mention that data is not enough to support this assumption. Studies from Australia reported disruptions to routine screening in 2020 resulting in a 1.1-3.6% increase in cervical cancer diagnoses, in addition to increase in cervical cancer mortality, and morbidity or both over the long term (~6–20 deaths) [3]. In this study, we are not in the position to declare something similar, since there were only nine patients diagnosed with cervical cancer and they all had treatment between 2-4 weeks later, after the diagnosis. It is important to note that with regards to our unit’s colposcopy service, there was a gap of two weeks, where all clinics had been cancelled with some doctors and nursing staff being redeployed to other medical areas. This would have unsurprisingly impacted on the wait-time-referral which has been reflected in the results of our study. Even after clinics started running, according to Trust’s guidelines, the number of face-to-face clinics had to be reduced, such as the slots available for each clinic, to reduce the exposure of staff and patients. This has caused problems with capacity and was addressed by increasing the number of clinics.

The impact of COVID-19 pandemic led the BSCCP, to introduce risk-based prioritization guideline to deliver the best and safest experience to patients. In the UK, however, there was a delay of two to three weeks before these guidance documents reached different Trusts. During this period of March to June 2020, primary screening programs in most areas of the country were on hold [2]. Similarly, other countries have noted that less women had cervical screening and received treatment after high grade cytology referral [4-6]. The cervical screening and colposcopy service have been globally affected by the pandemic. Plan for recovery have been implemented, where high grade cases have been prioritized and seen in colposcopy service before the low-grade cytology referrals [6].

The delay concerned not only the first assessment of patients but also the treatment, creating an extra stress for medical staff regarding the safety of the service provided. During this past year, many studies have been published focused on the impact of this pandemic on safety and quality of healthcare service provided by healthcare professionals [7,8]. It has been recognized that the pandemic caused a mental and physical burnout to health care professionals [9,10]. Awareness of mental and physical status of the staff is very important. In a recently published systematic review [11], it has been found that by providing clear guidelines and strategies, paying attention to the mental health issues, reducing the workload of health care professionals through adjusting their work shifts, reducing job-related stressors, and creating a healthy work environment may prevent or reduce burnout.

The COVID-19 pandemic is rapidly transforming the medical care system, with telemedicine or virtual meeting software platforms being one of the crucial drivers of change [12,13]. As the health sector continues to be on the front lines, medical centers can leverage on telemedicine to support their patients, protect their staffs, and conserve scarce medical resources [14]. But still key organizational, technological, and social factors require to improve adoption of telemedicine by patients and medical practitioners [15]. Since the start of the pandemic, telemedicine is becoming a more widely acceptable part of healthcare. Telemedicine is a term coined to the various entities of remote patient contact [16]. Traditional colposcopy though doesn’t allow telemedicine. Screening centers and colposcopy clinics should implement virtual consultations and dedicated helplines. The primary aims are to answer questions and alleviate fears of women for whom the scheduled contact (e.g., colposcopy/follow-up) has been postponed [2]. Tele colposcopy or digital colposcopy represents the merging between traditional colposcopy and new digital imaging technologies and allows the collection and transmission of digital colposcopy images and videos [17]. Digital colposcopy can be performed in real-time with communication between the colposcopist and the telecolposcopist. Implementation of virtual clinics may represent the colposcopy of the future. Studies have shown telemedicine being efficacious and largely accepted by patients for post-operative follow up [18,19]. However, further studies are needed to evaluate the efficacy and safety of virtual clinics for initial patient contact.

The main limitation of our study is the fact that it is retrospective and covers a very small period of time. Our data have been collected during the first wave of the pandemic. Departments, such as ours, had the time later on to audit the service and adjust the clinical practice according to the demand, but respecting the rules of “keeping distance” to stay safe during the period of this pandemic.

The unprecedented emergency precipitated by the COVID-19 pandemic has highlighted the strengths and weaknesses of our organizations and of our health-care policies. During an emergency, priorities, necessarily, change. Preparation is required to avoid the negative health and economic implications arising from COVID-19 and potential future emergencies. It is important to educate our patients, increase awareness of all relevant stakeholders (policymakers, hospital managers) about the potential impact of a pandemic to healthcare services. Colposcopy departments will need to add new technology and techniques, to be able to provide safe service in the right time.

Conclusion

Although it is early to accurately measure the impact of the COVID-19-related service reductions on cervical cancer outcomes including morbidity and mortality, we are presenting our study reporting a delay in colposcopy which will subsequently impact on the model and time of treatment proposed following colposcopy due to the disruption of histology and the cervical cancer services across the country due to COVID-19.

Acknowledgement

None.

Conflict of Interest

Authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- WHO (2020) Director-General’s opening remarks at the media briefing on COVID-19.

- Bouwer NI, Jager A, Liesting C, Koffland MJM, Brugts JJ, et al. (2020) Cardiac monitoring in HER2-positive patients on trastuzumab treatment: A review and implications for clinical practice. Breast 52: 33-44.

- Smith M, Hall M, Simms K, Killen J, Sherrah M, et al. (2020) Modelled Analysis of Hypothetical Impacts of COVID-19 Related distruptions on the National Cervical Screening Program. Report to the Department of Health. New South Wales: Cancer Research Division, Cancer Council NSW.

- Meggetto O, Jembere N, Gao J, Walker MJ, Rey M, et al. (2021) The impact of the COVID‐19 pandemic on the Ontario Cervical Screening Program, colposcopy and treatment services in Ontario, Canada: a population‐based study. BJOG 128(9):1503-1510.

- Castanon A, Rebolj M, Pesola F, Sasieni P (2021) Recovery strategies following COVID-19 disruption to cervical cancer screening and their impact on excess diagnoses. Br J Cancer 124(8): 1361-1365.

- Campbell C, Sommerfield T, Clark GRC, Porteous L, Milne AM, et al. (2021) COVID-19 and cancer screening in Scotland: A national and coordinated approach to minimising harm. Prev Med 151: 106606.

- Tsonis O, Diakaki K, Gkrozou F, Papadaki A, Dimitriou E, et al. (2021) Psychological burden of covid-19 health crisis on health professionals and interventions to minimize the effect: what has history already taught us? Riv Psichiatr 56(2): 57-63.

- Iskanderian RR, Karmstaji A, Mohamed BK, Alahmed S, Masri MH, et al. (2020) Outcomes and Impact of a Universal COVID-19 screening protocol for Asymptomatic Oncology Patients. Gulf J Oncolog 1(34): 7-12.

- Hruza GJ (2020) COVID-19 Pandemic: Impact on Healthcare in Missouri. Mo Med 117(3): 168-169.

- Misra-Hebert AD, Jehi L, Ji X, Nowacki AS, Gordon S, et al. (2020) Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Healthcare Workers’ Risk of Infection and Outcomes in a Large, Integrated Health System. J Gen Intern Med 35(11): 3293-3301.

- Sharifi M, Asadi-Pooya AA, Mousavi-Roknabadi RS (2021) Burnout among Healthcare Providers of COVID-19; a systematic Review of Epidemiology and Recommendations. Arch Acad Emerg Med 9(1): e7.

- Doshi A, Platt Y, Dressen JR, Mathews BK, Siy JC (2020) Keep calm and log on: Telemedicine for COVID-19 Pandemic Response. J Hosp Med 15(5): 302-304.

- Keesara S, Jonas A, Schulman K (2020) Covid-19 and health care’s digital revolution. N Engl J Med 382(23): e82.

- Hollander JE, Carr BG (2020) Virtually perfect? Telemedicine for COVID-19. N Engl J Med 382(18): 1679-1681.

- Bokolo AJ (2021) Exploring the adoption of telemedicine and virtual software for care of outpatients during and after COVID-19 pandemic. Ir J Med Sci 190(1): 1-10.

- Kemp MK, Liesman DR, Williams AM, Brown CS, Iancu AM et al. (2021) Surgery Provider Perceptions on Telehealth Visits During the COVID-19 Pandemic: Room for Improvement. J Surg Res 260: 300-306.

- Louwers JA, Kocken M, Harmsel WA ter, Verheijen RHM (2009) Digital colposcopy: ready for use? An overview of literature. BJOG 116(2): 220-229.

- Mojdehbakhsh RP, Rose S, Peterson M, Rice L, Spencer R (2021) A quality Improvement pathway to rapidly increase telemedicine services in a gynaecologic oncology clinic during the COVID-19 pandemic with patient satisfaction scores and environmental impact. Gynecol Oncol Rep 36: 100708.

- Ciavattini A, Carpini GD, Giannella L, Arbyn M, Kyrgio M, et al. European Federation for Colposcopy (EFC) and European Society of Gynaecological Oncology (ESGO) joint considerations about human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccination, screening programs, colposcopy, and surgery during and after the COVID-19 pandemic. Int J Gynecol Cancer 30(8): 1097-1100.

-

Aisha Bojang, Lina Antoun, Orestis Tsonis, Fani Gkrozou. COVID-19 Pandemic; Impact on the Colposcopy Service. W J Gynecol Women’s Health. 5(3): 2021. WJGWH.MS.ID.000612.

Colposcopy service, Covid 19 pandemic, Service provision, Human Papilloma Virus (HPV), Cervicitis

-

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.