Research Article

Research Article

Combination Local Therapy of Genitourinary Menopausal Syndrome Symptoms

Orazov МR1*, Radzinsky VE1, Balan VE2, Khamoshina МВ1, Toktar LR1 and Smetnik AA3

1People’s Friendship University of Russia, Russia

2Moscow Regional Research Institute of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Russia

3National medical research centre for obstetrics, Gynecology and perinatology named after academician VI Kulakov, Russia

Orazov MR, Professor of the Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology with a Course of Perinatology, Medical Institute, People’s Friendship University of Russia, Russia.

Received Date: April 14, 2020; Published Date: May 13, 2020

Abstract

Introduction: Genitourinary syndrome of menopause (GSM) is a pressing gynecological problem since the condition leads to the deterioration in the quality of life of postmenopausal women.

Objective: compare the efficacy of relief of GSM with intravaginal use of estriol monoproduct and a combination product containing estriol, micronized progesterone and Lactobacillus casei rhamnosus Doderleini.

Materials and Methods: the study enrolled 69 postmenopausal women aged 53.6±2.1 diagnosed with postmenopausal atrophic vaginitis. After screening, the patients were randomized into 2 groups: Group 1 (n=34) used 0.5 mg/day of estriol monoproduct intravaginal for 14 days, followed by a gradual dose reduction based on symptom relief until a maintenance dose was reached (i.e. 1 suppository 2 times a week), Group 2 (n=35) used intravaginal combination product in the form of capsules containing 0.2 mg of estriol, 2.0 mg of micronized progesterone and lyophilized culture of L. casei rhamnosus Doderleini – 341mg (2*107 CFU) (Trioginal, Besins Healthcare SA, Belgium). The product was prescribed to be taken at a dose of 2 capsules intravaginal 1 time/day for 20 days, then 1 capsule/day. Total duration of therapy in both groups was 12 weeks. After the end of therapy, patients were monitored for 12 weeks. To determine the efficacy of the treatment, subjective and objective clinical symptoms of GSM were evaluated using the adapted Nappi RE scale at the study visits. 5-point D. Barlow scale, vaginal pH, Bachmann’s Vaginal Health Index was additionally used. The main software for statistical analysis was the IBM SPSS 22 statistical package.

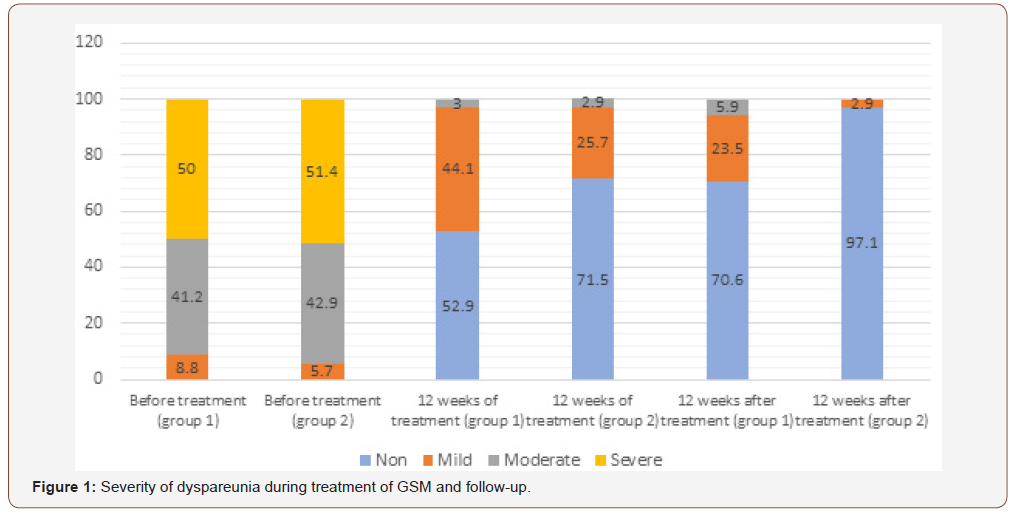

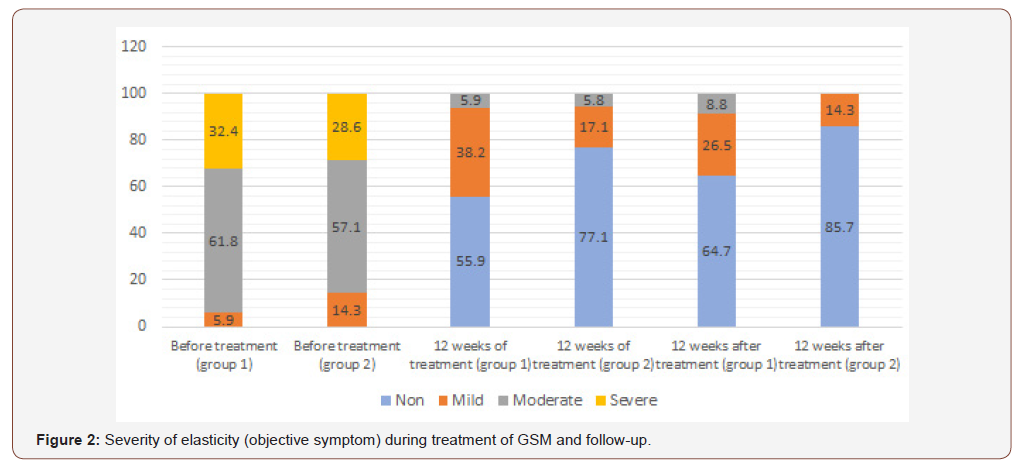

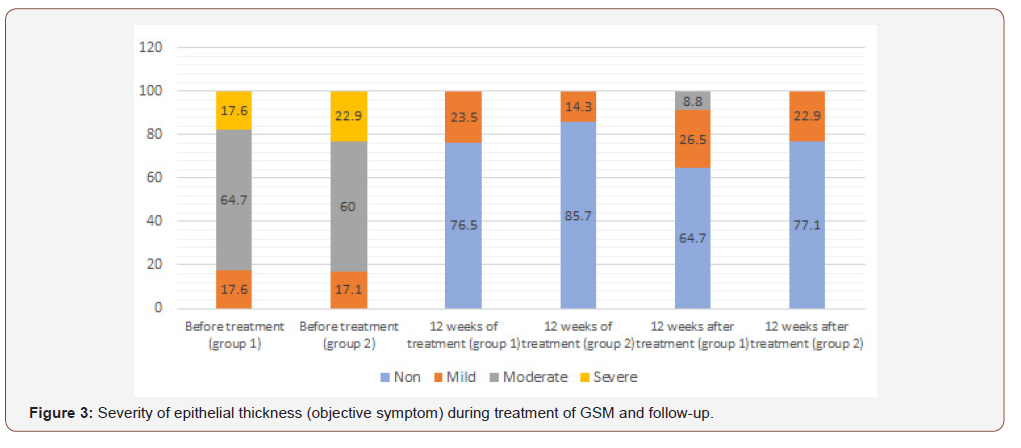

Results: After 12 weeks of treatment, complaints of dyspareunia resolved completely in 18 (52.9%) patients in Group 1 and 25 (71.5%) in Group 2, p<0.05; 12 weeks after the end of therapy: in 24 (70.6%) patients in Group 1 and in 34 (97.1%) patients in Group 2, p<0.05. Improvement in elasticity after 12 weeks of therapy was observed in 19 (55.9%) and 27 (77.1%) patients of Group 1 and Group 2, respectively (p<0.05); normal epithelial thickness was observed in 26 (76.5%) and 30 (85.7%) patients, respectively (p<0.05). 12 weeks after the end of treatment in Group 1 and Group 2, improvement in elasticity was observed in 22 (64.7%) and 30 (85.7%) patients; normal epithelial thickness was observed in 22 (64.7%) and 27 (77.1%) patients, respectively (p<0.05). For the rest of analysed parameters (D. Barlow scale, pH, Bachmann’s Vaginal Health Index) statistical analysis did not reveal any statistically significant differences between the groups in the dynamics of treatment and follow-up.

Conclusion: Thus, local combination hormone therapy with probiotic support can be an effective treatment option for genitourinary syndrome of menopause since it helps to enhance proliferative processes, improve blood circulation, restore biocenosis and relieve symptoms of coital pain. Compared with local estriol monotherapy, having a comparable effect on the condition of vaginal epithelium, it is significantly more effective for eliminating the symptoms of sexual dysfunction.

Keywords: Genitourinary syndrome of menopause; Vulvo-vaginal atrophy; Local hormone therapy

Introduction

Due to increasingly aging of the population the problem of relieving symptoms caused by age-related changes in the female uro genital tract during menopause remains one of the most pressing problems of the world gynaecology. The widely used terms “uro genital syndrome”, “atrophic vulvovaginitis”, including the diagnosis “postmenopausal atrophic vaginitis” in ICD-X (N95.2) and similar definitions do not reflect the entire scope of modern ideas about the cause, pathogenesis and clinical presentation of the syndrome.

In 2014, the new term “genitourinary syndrome of menopause” (GSM) was introduced into clinical practice to replace the term “vulvovaginal atrophy”, which was commonly accepted earlier and did not fully reflect the essence of the problem. The term GSM emphasizes the many genital, sexual and urinary symptoms associated with the anatomical and functional changes in the vulvovaginal tissues that occur during aging [1].

According to the modern integrative definition, GSM is a complex of symptoms that includes physiological and anatomical changes that occur secondary not only to estrogen deficiency but also other sex steroids in women in the external genitalia, perineum, vagina, urethra and bladder. The use of the new term by all related specialists who deal with the problem of urogenital disorders in women is of high clinical significance since it allows us to consider the complex effect of all sex steroid hormones on the urogenital region [2-4].

According to modern recommendations for menopausal hormone therapy and maintaining the health of older women, local estrogen therapy is the “gold” standard for the treatment of vulvovaginal atrophy. Moreover, local estrogen therapy in low doses is preferable for women with complaints of vaginal dryness or associated discomfort during sexual activity. Vaginal oestrogens are generally more effective for alleviating urogenital symptoms than oral products due to no liver metabolism and a quick vaginal response [5,6]. The modern polyhormonal concept of the pathogenesis of GSM opens up new potential opportunities for studying ways to optimize its traditional local estrogen therapy by additionally prescribing topical forms of products of other sex hormones, for example, a combination of estriol with progesterone, androgens (DHEA), thus turning the hormonal local monotherapy of GSM into hormonal combination local therapy. As is shown in clinical practice, complex hormonal impact gives better results in a shorter time. After local saturation with estriol and progesterone, vaginal colonization with the necessary lactobacilli becomes more favourable, which is necessary to restore normal vaginal micro flora [7,8].

In Russia, in addition to estriol monoproduct, another product is used for intravaginal use in GSM, which is a combination of estriol with micronized progesterone and lactobacillus casei rhamnosus Doderleini (LCR) in vaginal capsules (Trioginal, Besins Healthcare SA, Belgium). The main advantage of the complex product is micronized progesterone in its content with its effects that are not related to the classical role of sexual reproduction. Oestrogens promote the growth and maturation of the vaginal epithelium, as well as the synthesis and accumulation of glycogen, which is a key substrate for the activity of lactobacilli, which must be in the lumen of the vagina in order to be utilized by lactobacilli. The process of release of glycogen from the vaginal epithelium requires participation of progesterone, which contributes to the formation of intermediate layers of vaginal epithelium and its natural desquamation. A similar situation takes place in the hormone-dependent tract of the lower urinary tract, where oestrogens perform the same critical physiological functions for urothelium, ensuring its growth and maturation, synthesis and accumulation of glycogen, as well as synthesis of local immunity factors (immunoglobulin’s) and protective mucopolysaccharides – glycosaminoglycan’s (hyaluronic acid and its sodium and zinc salts, chondroitin sulphate, glycoproteins, mucin) that make up the surface glycocalyx of the bladder mucosa – a powerful natural system of antibacterial and anti-inflammatory protection of the lower urinary tract [9-11]. However, complete natural antibacterial protection of the urothelium of the urethra and bladder in women is impossible without progesterone, which is related to the fact that oestrogens affect the synthesis of glycosaminoglycan’s in urothelium of the bladder, and progesterone affects their release by urothelium out into the lumen of the bladder [12-13]. Moreover, it is important to emphasize non-reproductive effects of micronized progesterone: analgesic – due to suppression of the synthesis of prostaglandins; neuroprotective and neuroreparative – due to selective effect on the receptors of neurotransmitters; regulatory – due to increased synthesis of muscle protein [14].

Thus, modern literature indicates that in order to ensure normal anatomical and functional state of the lower urinary and genital tracts in women, a sufficient level of both estrogen and progesterone is necessary [15-17]. Disorder of the synthesis and release of glycogen secondary to deficiency of sex hormones leads to rapid alkalization of the vagina and the development of dysbiotic processes – a decrease in the number of lactobacilli and an excessive growth of pathogenic and conditionally pathogenic microorganisms [18]. According to the data of Hillier SL, et al. in a detailed analysis of vaginal micro flora of 73 postmenopausal women who did not receive hormonal therapy, 49% had no lactobacilli at all, while in those who had the concentration was 10-100 times lower than in premenopausal women. According to other studies, lactobacilli predominate in the vaginal microflora only in 13% of postmenopausal women not taking hormonal therapy. In postmenopausal women, the most common microorganisms are anaerobic gram-negative bacilli and gram-positive cocci [19]. Thus, the normalization of vaginal microflora is one of the goals of treatment of GSM. Moreover, recently there has been evidence that normalization of vaginal microflora not only reduces the frequency of relapse of urinary tract infections in women in peri- and postmenopausal women, but also contributes to a more rapid relief of GSM symptoms [20-21]. The goal of lactobacilli in products for the treatment of GSM symptoms is to reduce pH and maintain normal biocenosis, preventing colonization of the vagina by pathogenic bacteria.

The goal of this study was to compare the efficacy of the relief of symptoms of genitourinary syndrome of menopause with intravaginal use of estriol monoproduct and a combination product containing estriol, micronized progesterone and Lactobacillus casei rhamnosus Doderleini.

Materials and Methods

During the study, the following criteria for the inclusion/exclusion of patients were observed:

Inclusion criteria: Women in the early post menopause (duration of post menopause from 1 year to 3 years) in accordance with the STRAW+10 criteria; the diagnosis of “Postmenopausal atrophic vaginitis” (ICD No. 95.2) (GSM), confirmed by investigations; sexual life (vaginal sex at least 2 times a month); negative PAP test; informed consent of patients to participate in the study.

Exclusion criteria: Reproductive age; previous local or systemic menopausal hormone therapy; lack of signs of vaginal atrophy; hormone-dependent tumours; vaginal bleeding of unknown cause; malignant tumours of the reproductive system, as well as diseases of the vulva, neck and vagina associated with HPV infection (intraepithelial neoplasia).

In accordance with inclusion/exclusion criteria, 69 women who turned to the clinic for conservative treatment of GSM were enrolled in the study. All patients were randomized into 2 groups and received only local hormonal therapy. Patients of Group 1 (n=34) used intravaginal suppositories with estriol at a dose of 0.5 mg/day for 14 days, followed by a gradual dose reduction as symptoms improved until a maintenance dose of 1 suppository 2 times a week. Patients of Group 2 (n=35) used intravaginal combination product in the form of capsules (Trioginal, Besins Healthcare SA, Belgium) containing estriol (0.2 mg), micronized progesterone (2.0 mg) and a lyophilized culture of Lactobacillus casei rhamnosus Doderlein (341mg (2x107 CFU)). The product was prescribed at a dose of 2 capsules 1 time/day for 20 days, then 1 capsule/day. Total duration of therapy in both groups was 12 weeks.

The study consisted of two stages (treatment phase of 12 weeks and follow-up phase of 12 weeks) and three patient visits (Visit 0 – at the phase of inclusion in the study, Visit 1 – 12 weeks after the start of therapy and Visit 2 – 12 weeks after the end of therapy).

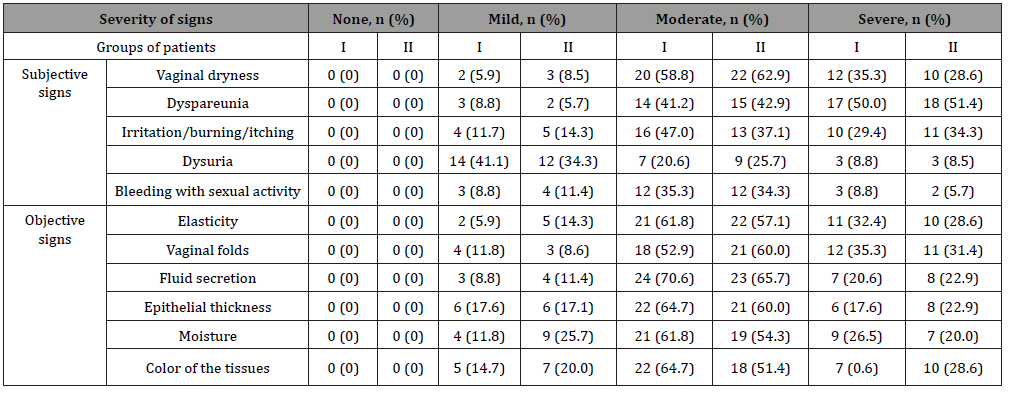

Subjective (vaginal dryness, dyspareunia, irritation/burning/ itching, dysuria, bleeding with sexual activity) and objective (elasticity, vaginal folds, fluid secretion, epithelial thickness, moisture) clinical symptoms of GSM were evaluated using the adapted Nappi RE scale, their severity was determined on the scale from 0 to 3 (0 – no symptoms, 1 – mild symptoms, 2 – moderate symptoms, 3 – severe symptoms) [4]. Subjective symptoms were evaluated by the patient, while objective symptoms were evaluated by the physician during the study visits.

All patients underwent gynecological examination, where special attention was paid to the condition of the vulva, vaginal mucosa and cervix. Dynamics of the severity of symptoms of atrophic vulvovaginitis (dryness, burning/itching, dyspareunia, bleeding from the vagina after intercourse, recurrent discharge from the genital tract) was evaluated using 5-point D. Barlow scale [22]. Vaginal pH value was additionally determined: litmus indicator was inserted into the vagina with an exposure of 30 seconds; the result was compared against a 3.0 – 7.0 pH color scale. Routine colpocytology allowed evaluating the karyopyknotic index (KPI) of the vaginal epithelium, defined as the percentage of surface cells with nuclear pycnosis to the total number of cells in a colpocytogram. Based on the gynecological examination, colposcopy pattern and measurement of vaginal pH, Bachmann’s Vaginal Health Index was determined in points. Colposcopy was performed to all patients in order to rule out pathological processes of the cervix and verify epithelial atrophy of the vaginal walls. Hyperplastic and tumour processes of the cervix, body, and uterine appendages were ruled out by sonographic, papel biopsy and PAP test.

The main software for statistical analysis was the IBM SPSS 22 statistical package. Statistical analysis consisted of research and descriptive methods, with the required power of the study of 80% (beta error of 20%) and the allowable alpha error of 5%. Demographic data of patients, baseline data were presented as rates or percentages, or using mean (standard deviation), median (interquartile range), minimum and maximum, depending on the type of variable. To test the hypothesis about homogeneity of the study groups at baseline, as well as after treatment, the null hypotheses (absence of differences between the groups) were tested using Student’s t-test (for interval indicators with normal distribution in the study population), Mann-Whitney test (for ordinal indicators or for interval indicators with a distribution other than normal) or χ2 test (for qualitative characteristics). In case of statistically significant differences between the groups, the magnitude of the differences between the groups was estimated.

Study Results

Table 1:

The age of all patients enrolled in the study did not exceed 60 years (mean age 53.6 ± 2.1 years). Duration of post menopause – from 1 to 3 years (2.04 ± 0.3 years on average), duration of symptoms of GSM – from 1 to 3 years (1.4 ± 0.96 years on average). At the time of their visit to the doctor, no patient had been receiving systemic or local hormonal therapy. At the time of enrolment in the study, all patients had subjective and objective symptoms of GSM according to the Nappi RE scale of varying severity, without statistically significant differences between the groups (p>0.05) (Table 1).

Gynecological examination showed atrophic changes in the labia major and labia minor and perineum region of varying severity. Vaginal mucosa in all patients was pale, thinned, smoothed, and inelastic, sometimes with petechial haemorrhages, without natural moisture. No signs of inflammation, pathological discharge were detected.

When evaluating the severity of symptoms of vaginal atrophy at the time of enrolment in the study on a 5-point D. Barlow scale, the values varied in the range from 3.2 to 4.1 points. Measurements of vaginal pH indicated alkalization of the vaginal discharge – average pH in all patients was 6.3±0.4. Calculation of karyopyknotic index during colpocytology showed low estrogen deprivation of the vaginal wall: from 28.2% to a maximum of 59.6%, while the average KPI in the investigated population was 38±3.44%. Bachmann’s Vaginal Health Index averaged 2.15±0.98 points. It is important to note that the vaginal mucosa was easily injured when touched with an instrument to collect material for cytological evaluation. Intergroup comparison of all the above initial patient data showed the absence of statistically significant differences, which indicates the homogeneity of analysed groups of patients according to the investigational characteristics (p>0.05).

Gynecological examination, including with the use of a colposcopy, after 12 weeks of therapy, revealed that almost all the women of the study population had a significant improvement in the condition of the skin and mucous membrane of the vulva and vagina, which had pale pink color and had sufficient moisture. There was also a subjective decrease in complaints of itching, burning, dryness and dyspareunia in patients, increased epithelial elasticity, new normal epithelium, no more petechial haemorrhages on the vaginal mucosa.

Efficacy of therapy was analysed on the population of all patients enrolled in the study, 12 weeks after the start of treatment. Persistence of achieved therapeutic effects was evaluated 24 weeks after the start of therapy (12 weeks after the end of treatment), based on the severity of the objective and subjective symptoms of GSM according to the adapted Nappi RE scale.

Analysis of subjective symptoms showed that after 12 weeks of therapy (Visit 1), complaints of dyspareunia were resolved in 18 (52.9%) patients in Group 1 an in 25 (71.5%) in Group 2, p<0.05. An interesting fact was that 12 weeks after the end of therapy (Visit 2), further positive dynamics was observed in both groups with regard to relief of dyspareunia, which differed between the groups: in Group 1, the symptoms subsided completely in 24 (70.6%) patients, i.e. they persisted in 30% of cases, while in Group 2 the symptoms subsided completely in 34 (97.1%) patients, p<0.05, Figure 1. For the remaining subjective symptoms of GSM (vaginal dryness, irritation/ burning/itching, dysuria, bleeding with sexual activity), there were no statistically significant differences in the dynamics of treatment and follow-up (p>0.05) (Figure 1).

When evaluating the objective symptoms of GSM, a number of statistically significant differences were observed between the groups. Improvement in elasticity after 12 weeks of therapy (Visit 1) was observed in 19 (55.9%) and 27 (77.1%) patients of Group 1 and Group 2, respectively (p<0.05); normal epithelial thickness was observed in 26 (76.5%) and 30 (85.7%) patients, respectively (p<0.05). Moreover, 12 weeks after the end of treatment (Visit 2) in Group 1 and Group 2, improvement in elasticity was observed in 22 (64.7%) and 30 (85.7%) patients, Figure 2; normal epithelial thickness was observed in 22 (64.7%) and 27 (77.1%) patients, respectively (p<0.05), Figure 3. For the remaining analysed objective symptoms (vaginal folds, fluid secretion, moisture, color of the tissues), there were no statistically significant differences in the dynamics of treatment and follow-up (p>0.05), Appendix 1 & 2.

For the rest of analysed parameters (D. Barlow scale, pH, Bachmann’s Vaginal Health Index) statistical analysis did not reveal any statistically significant differences between the groups. When evaluating the severity of symptoms of vaginal atrophy on a 5-point D. Barlow scale after 1 and 3 months after therapy, the values varied in the range from 1.8 to 2.8 and from 1.8 to 2.4 points, respectively. 3 months after the start of therapy, pH values reached, on average, 4.1 ± 0.3. Bachmann’s Vaginal Health Index was on average 4.15 ± 0.46 and 4.65 ± 0.59 points, respectively, 1 and 3 months after the procedure. According to the results of colposcopy, the degree of epithelial atrophy corresponded to 1.25 ± 0.12 and 1.45 ± 0.16 points; no abnormal colposcopy symptoms (acetabular epithelium, puncture, mosaic) were observed after treatment.

Therefore, combined estrogen-progesterone local hormonal therapy with probiotic support compared with estriol monotherapy is a more effective method of treating genitourinary syndrome of menopause according to some subjective and objective signs (dyspareunia, elasticity and epithelial thickness). These differences are likely to be associated with increased proliferative processes, improved blood supply, restoration of microbiocenosis, and rapid relief of the symptoms of dyspareunia when using combination therapy of GSM.

Discussion

Published recommendations of The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) for the diagnosis and management of menopause (Menopause: diagnosis and management) in November 2015 confirmed that not all menopausal problems are related to vasomotor symptoms; the problem of vulvovaginal atrophy was highlighted. Even without the use of systemic MHT, local estrogen therapy by itself is quite effective for relieving symptoms and treating atrophic epithelial vaginal diseases [23,24].

The document states that local vaginal estrogen can be used as much as necessary. These recommendations also indicate that there is no risk of hyperplasia and, therefore, there is no need to control endometrium in and additional prescription of progesterone to protect the endometrium when using topical estrogen products. Other scientific documents, including a review of the Cochrane Database, made similar conclusions [25-28].

However, despite the logic of monohormonal estrogen concept for dealing with atrophy, one cannot but admit that this is a very one-sided view of the matter. It is abundantly obvious that the genitals, all structures of the lower urinary tract, as well as the musculo- fascial apparatus of the pelvic floor, the neurothelium and endothelium of the indicated anatomical regions have receptors for all sex steroids: oestrogens, progesterone and androgens [29-31].

Modern idea of GSM from the perspective of polyhormonal concept allows to deal with a variety of urogenital disorders, including chronic pelvic pain syndrome in women, more effectively or to be justified support in the surgical treatment of stress urinary incontinence.

Despite the fact that all modern guidelines state the lack of the need to include gestagens (natural progesterone or its analogs) in topical estriol therapy, the new definition of GSM and its polyhormonal concept allows to claim that progesterone is still very important for the treatment of urogenital disorders for the complete effect [20]. A decrease in the proportion of lactobacilli due to both a deficiency of oestrogens and a deficiency of progesterone and associated disruption of their synthesis and release of glycogen exacerbates the course of vaginal atrophy.

The use of combination estriol-progesterone therapy with a probiotic is not only justified but advisable since there are receptors for all sex steroids in the vagina, urethra, bladder and pelvic floor muscles. Progesterone effects on tissues are no less important to restore their physiological state.

Our study, even if on a small sample, showed significant and versatile positive and, importantly, long-term effects of combination local hormonal therapy with a product containing micro doses of estriol, micronized progesterone and lyophilized culture of L. casei rhamnosus Doderleini – 341mg (2x107 CFU) compared with estriol monotherapy.

Acknowledgement

None.

Conflict of Interest

Authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Portman DJ, Gass ML (2014) Vulvovaginal Atrophy Terminology Consensus Conference Panel. Genitourinary syndrome of menopause: new terminology for vulvovaginal atrophy from the International Society for the Study of Women's Sexual Health and the North American Menopause Society. Menopause 21(10): 1063-1068.

- Portman DJ, Gass ML (2014) Genitourinary syndrome of menopause: new terminology for vulvovaginal atrophy from the International Society for the Study of Woman’s Sexual Health and the North American Menopause Society. Maturitas 79(3): 349-354.

- Nappi RE, Palacios S, Panay N, Particco M, Krychman ML (2016) Vulvar and vaginal atrophy in four European countries: evidence from the European REVIVE Survey. Climacteric 19(2): 188-197.

- Nappi RE, Martini E, Cucinella L, Martella S, Tiranini L, et al. (2019) Addressing Vulvovaginal Atrophy (VVA)/Genitourinary Syndrome of Menopause (GSM) for Healthy Aging in Women. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 10: 561.

- Glaser RL, Zava DT, Wurtzbacher D (2008) Pilot study: absorption and efficacy of multiple hormones delivered in a single cream applied to the mucous membranes of the labia and vagina. Gynecol Obstet Invest 662: 111-118.

- Del Pup L, Di Francia R, Cavaliere C, Facchini G, Giorda G, et al. (2013) Promestriene, a specific topic estrogen. Review of 40 years of vaginal atrophy treatment: is it safe even in cancer patients? Anticancer Drugs 24(10): 989-998.

- Muhleisen AL, Herbst-Kralovetz MM (2016) Menopause and the vaginal microbiome. Maturitas 91: 42-50.

- Palacios S, Mejía A, Neyro JL (2015) Treatment of the genitourinary syndrome of menopause. Climacteric Suppl 1: 23-29.

- Tyuzikov IA, ZHilenko MI, Polikarpova SR (2018) Modern opportunities for optimizing local hormone therapy for urogenital disorders in women based on the combined use of vaginal forms of estriol and progesterone. Gynecology 20(1): 117-125.

- Parsons CL (2007) The role of the urinary epithelium in the pathogenesis of interstitial cystitis/prostatitis/urethritis. Urology 69 (4 Suppl): 9-16.

- Sivick KE, Schaller MA, Smith SN, Mobley HL (2010) The innate immune response to uropathogenic Escherichia coli involves IL-17A in a murine model of urinary tract infection. J Immunol 184(4): 2065-2075.

- Sufiiarov A.D. Menopausal cystitis. Clinical lectures and practical recommendations. Meddok, 2007.

- Tiuzikov IA, Kalinchenko S Iu (2010) Endocrinological aspects of chronic cystitis in women. Experimental and clinical urology 3: 120-126.

- Taraborrelli S (2015) Physiology, production and action of progesterone. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 94 Suppl 161: 8-16.

- Robinson D, Toozs-Hobson P, Cardozo L (2013) The effect of hormones on the lower urinary tract. Menopause Int 19 (4): 155-162.

- Hillard T (2010) The postmenopausal bladder. Menopause Int 16(2):74-80.

- Apetov SS, Kalinchenko S Iu, Vorslov LO (2013) The role of progestogens in hormone replacement therapy. Are gestagens needed for surgical menopause? Therapist 11: 46-50.

- Mehta A, Bachmann G (2008) Vulvovaginal complaints. Clin Obstet Gynecol 51(3): 549-555.

- Nyirjesy P (2007) Postmenopausal vaginitis. Curr Infect Dis Rep 9(6): 480-484.

- Pushkar D, Gvozdev M (2018) Dynamics of symptoms of genitourinary menopausal syndrome and the frequency of recurrence of lower urinary tract infection in women in peri-and postmenopausal patients with combined therapy with Trioginal. Gynecology 20(6): 67-72.

- Kuzmenko AV, Kuzmenko VV, Gyaurgiev TA (2019) Experience of application of hormonal and probiotic therapy in the complex treatment of women in peri- and postmenopausal with chronic recurrent bacterial cystitis in the background of vulvovaginal atrophy. Urologiia 3: 66-71.

- Barlow DH, Samsioe G, van Geelen IM (1997) A study of European women experience of the problems of urogenital aging and its management. Maturitas 27(3): 239-247.

- Yureneva SV, Glazunova AV, Eprikyan EG, Donnikov AE, Ezhova LS (2017) Clinical and pathogenetic aspects of the treatment of vulvovaginal atrophy in postmenopausal women. Obstetrics and gynecology 6: 143-50.

- Bachmann G (1995) Urogenital ageing: an old problem newly recognized. Maturitas 22 Suppl: S1-S5.

- Sturdee DW, Panay N (2010) Recommendations for the management of post-menopausal vaginal atrophy. Climacteric 13(6): 509-522.

- Lethaby A, Ayeleke RO, Roberts H (2006) Local oestrogen for vaginal atrophy in postmenopausal women. Cochrane Database Syst Rev (8): CD001500.

- Al-Baghdadi O, Ewies AA (2009) Topical estrogen therapy in the management of postmenopausal vaginal atrophy: an up-to-date overview. Climacteric 12(2): 91-105.

- Pitkin J (2018) BMS- Consensus statement. Post Reprod Health 24(3): 133-138.

- Manukhin IB, Tumilovich LG, Gevorkian MA, Manukhina EI (2017) Gynecological endocrinology. Clinical lectures M: GEOTAR Media.

- Tiuzikov IA, Kalinchenko S Iu, Apetov SS (2013) Male gender or unresolved issue of both sexes? Experimental and clinical urology 4: 40-48.

- Tiuzikov IA, Kalinchenko S Iu, Apetov SS (2014) Androgen deficiency in women in urogynecological practice: patophysiological mechanisms, clinical masks and pharmacotherapy with transdermal forms of testosterone. Russian Bulletin of obstetrician and gynecologist 1: 33-43.

-

Orazov МR. Combination Local Therapy of Genitourinary Menopausal Syndrome Symptoms. W J Gynecol Women’s Health. 3(5): 2020. WJGWH.MS.ID.000575.

Genitourinary syndrome of menopause, Vulvo-vaginal atrophy, Local hormone therapy, Urogenital syndrome, Atrophic vulvovaginitis

-

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.