Review Article

Review Article

Black Maternal Mortality-The Elephant in the Room

Rolanda L Lister1*, Wonder Drake1, Scott Baldwin H1 and Cornelia Graves2

1Vanderbilt University Medical Center, USA

2Saint Thomas Midtown Hospital, USA

Rolanda L Lister, Assistant Professor, Obstetrics and Gynecology, Vanderbilt University Medical Center, 1161 21st Avenue South B-1118 Medical Center North, USA.

Received Date: November 15, 2019; Published Date: November 22, 2019

Abstract

Maternal mortality is on the rise in the United States and it disproportionately affects black women. The reasons for this staggering discrepancy hinge on three central issues: First, black women are more likely to have pre-existing cardiovascular morbidity that increase the risk of maternal mortality. Second, black women are more likely to experience adverse pregnancy outcomes which puts them at risk for developing long-term cardiovascular disease. Third, racial bias of providers and perceived racial discrimination from patients (the elephant in the room) impacts black patients’ trust in their providers and the medical community at large. Reducing black maternal mortality involves a multi-tiered approach involving the patient, provider and public health policy.

Keywords:Maternal mortality; Blacks; Whites

The Problem

Black maternal mortality is on the rise in the United States and cannot be fully explained by socioeconomic factors and limited access to care.

Solutions

Obstetric providers will encourage more African American women to engage the health care system if they treat black women with respect and compassion while delivering continuity of care. Other interventions aimed at reducing maternal mortality at large will also reduce black maternal mortality. Preconception, maternal comorbidities that lead to peripartum and cardiovascular complications (obesity, chronic hypertension, Type 2 diabetes) should be medically optimized. During pregnancy, women who have heart disease should be cared for via a team-based approach using “cardio-obstetrics” [1]. Additionally, it is incumbent on obstetricians who are often the primary care providers for reproductive aged women to highlight to the broader medical community of primary physicians that pregnancy essentially is a “stress test” and a window into the future health of those women. Black women who experience pregnancy complications (GDM, Preeclampsia, SGA, preterm birth) are at greatest risk for cardiovascular disease and should be linked with primary providers in the immediate postpartum period while in the hospital. Patients that have state and federally sponsored health care benefits beyond the immediate post-partum period should have extended benefits for their entire lives. Hospitals that serve black women should have expansion of resources to improve their quality of care to this population.

Presentation

Entry into motherhood is one of the most basic natural processes that is the foundation of humankind existence. The Millennium Development aspired a 75% reduction in maternal mortality worldwide [2,3]. This led to an international effort in both developing and developed countries to concentrate efforts on the reduction of maternal mortality [2,4].

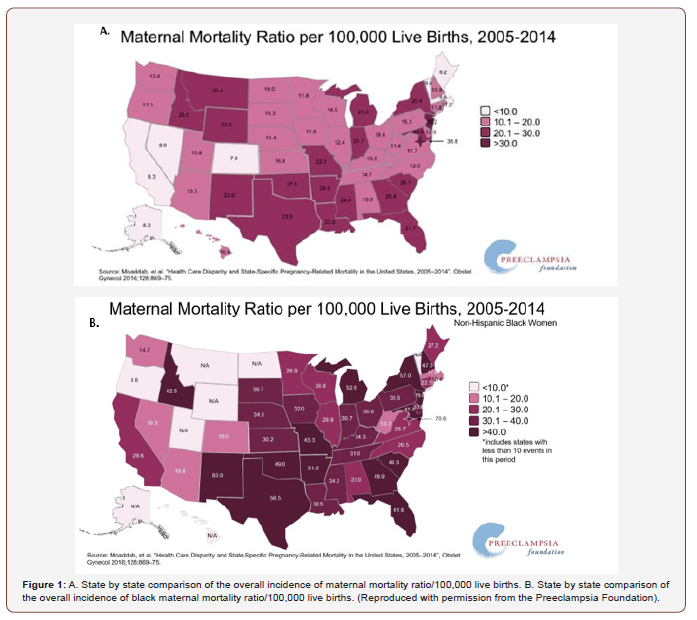

Contrary to other wealthy nations countries, the United States has a disturbing trend upward, with a staggering incidence of 26.4/100,000 compared to other first world countries such as Italy (4.2/100,000), Denmark (4.2/100,000) and Finland (3.2/100,000) who have the lowest maternal mortality rates [5]. Moreover, when assessing the national black maternal mortality rate, it is quadruple [6] that of non-Hispanic white women5. Even in states such as California that appeared to buck the national trend (8.3/100,000), Black women still died at triple the rate (26.6/100,000) in that state (Figure 1) [6].

Commonly cited reasons for the disparity observed include lower socioeconomic status and lack of prenatal care [7]. While each of these factors do contribute to the increase in maternal mortality overall, the disparity between maternal mortality between blacks and white mothers cannot be fully explained by these factors alone.

Black women are more likely to have perinatal complications that confer a higher risk of cardiovascular disease despite similar socioeconomics. For example, in a cohort of 10,755 women all whom were on Medicaid insurance who gave birth during calendar years 1994-2004, compared to whites, Hispanic women had a lower odd for preterm birth. However, African-American women had a greater odd for preeclampsia, small for gestational age infants and preterm birth [8]. These women presumably had similar socioeconomic status but had differential perinatal outcomes. Furthermore, Berg et all evaluated 4,693 maternal deaths from 1998-2005 and determined that for whites, being married conferred protection against maternal mortality but was not protective for black women [9]. Early access to prenatal care is associated with reduced risk of maternal death and the lack thereof is associated with increased risk of maternal death [9]. However, even when black women have prenatal care and seek it early, the disparity of maternal death persists. In this same study that evaluated the risk of maternal deaths with the onset of prenatal care, blacks had four times the risk of maternal death even when presenting for prenatal care in all trimesters compared to whites.

Site of care has been evaluated as a potential culprit in the disparity of severe maternal mortality. The majority (75%) of black pregnant women are cared for by a (25%) minority of hospitals [10]. The hospitals that treated a high volume of black patients were also more likely to be urban in location and a teaching hospital. The patients were also more likely to have co-morbid conditions such as prior cesarean delivery blood disorders, hypertensive disorders of pregnancy, asthma, multiple gestations, placental disorders, gestational diabetes, obesity and cardiac disease. After correction of co-morbidities, the site of care seemed to translate to a higher rate of severe maternal morbidities in African American women. The authors concluded that improving the quality of care at these hospitals would reduce the racial disparity of severe maternal morbidity [10]. Hospitals should be given the requisite education and resources to address common causes of severe maternal morbidity and mortality or should have well-established pipelines for referral and transport to appropriate tertiary care settings.

Racial disparity exists in maternal mortality despite correcting for commonly cited reasons. Thus, it is imperative to explore other potential etiologies for the disparities including racial bias. Sentinel events including the Tuskegee Syphilis Trial have served as evidence too many to blacks that the medical community cannot be trusted. One must give weight to the perception that many black pregnant women believe that their lives are not valued to the degree of their white pregnant counterparts. Twenty-nine black women who underwent focus questionnaires describe differential treatment by staff based on their insurance status (public versus private) and describe a lower quality of prenatal care based on racism from providers. Furthermore, they describe their interactions with their doctors or supporting staff as prejudiced. Many experiences were placed in the context of life experiences of systematic racism [11]. On the contrary, physicians and other healthcare providers and workers would likely challenge the notion that they treat patients differently solely based on their race or socioeconomic class. While there may not be evidence that differential treatment of black pregnant patients leads to maternal death, literature does support that black patients do receive differential treatment. For example, black cancer patients needing chemotherapy were less likely to be counseled about fertility preservation [12]. Furthermore, in a pediatric cohort of patients with confirmed appendicitis, black patients were less likely to receive analgesia despite similar pain scores [13]. In the minds of many black women, the perception of racial bias is their reality and may impact their willingness to engage with OB providers. In order to eliminate this disparity, courageous self-reflection about racial bias can be the first step in tackling this systemic and pervasive problem [14].

It is Time to Act

Maternal mortality has both acute and long-term consequences on the mother’s family, leaving her relatives to grow up in a singleparent home or orphaned which leads to cyclical poverty [15,16]. Each maternal death leads to the psychological and economical burdens for the remaining family which affect her local community. The crisis of black maternal mortality and the persistent disparities threatens to widen the perception of racism between people of color and the medical community. The international implications are such that as global positions shift, our relatively high maternal mortality rate challenges the dogma that the United States as a country is the champion of human rights. The consequences of maternal death are illustrated in Figure 2.

Entry into motherhood is a human right and strategies to prevent maternal death must be tailored to the preventable underlying causes. Implementing strategies to reduce maternal death will also affect the reduction of death in black women. In addition to focusing on optimizing pre-existing medical conditions, reducing obesity, identification of at women with cardiovascular risks after pregnancy complications have occurred (preeclampsia, GDM, SGA), we must address racial bias in the delivery of obstetric care.

Using Social Determinants of Health to Individualize Health Care

The social determinants of health are the conditions in which we are born, live, learn, work, play, worship and age according to Healthy People 2020. Utilization of prenatal care in some blacks may be undermined by the social determinants of adverse maternal health. Black women are disproportionately subject to unsafe housing, lack of affordable transportation, lack of insurance, and lack of partner support as black men are more likely to be incarcerated. Addressing psychosocial factors are likely to improve utilization of pregnancy care. However, this alone is insufficient in addressing racial disparities. We must delve further into bias and discrimination as a factor in poor maternal outcomes.

Expand Inter-Conception Maternity Coverage

Expanding coverage outside of the immediate post-partum period to our most vulnerable population will ensure that patients who are at the highest risk of cardiovascular sequelae be plugged into the health care system immediately after the adverse perinatal event. Since most reproductive aged women have OBGYNS as their sole primary provider, obstetric providers are uniquely positioned to link women with risk factors for cardiovascular disease with physicians skilled in treatment of cardiovascular disease who prevent and manage complications long-term. Black women are least likely to follow up in the post-partum period [17]. Since post-partum follow-up at 6-8 weeks among recently delivered patients is inconsistent and ranges from 30-80%, the immediate post-partum period may be a more ideal time to influence longterm cardiovascular health of black patients who have had the complication of preterm birth, preeclampsia or gestational diabetes [1,18-20]. Since maternal health in linked to long-term cardiovascular health, it stands to reason that federally or state sponsored insurance should cover a mother during her entire life as opposed to truncating her insurance 6-12 weeks after the birth of her child. Obstetric providers connecting the pregnant patient to primary care providers to address cardiovascular issues.

Addressing Perceptions of Racial Prejudice

Whether it is due systemic issues such as racism, implicit bias in the medical community amongst its providers or suspicion of the medical establishment (which has not always been transparent to people of color) [21], we must acknowledge that the conversation must not be truncated at socioeconomic factors alone. If we intend to change the narrative that black pregnant patients are discriminated against, we must employ measures to ensure that black women are being listened to. For instance, Hwa et al. describe 204 African American pregnant patients and their 21 ethnically diverse providers demonstrated that patientprovider communication had a positive effect on trust in provider and on prenatal care satisfaction [22]. In a qualitative study of 22 African American Women, the qualities important to effective communication were (a) demonstrating quality patient-provider communication, (b) providing continuity of care, (c) treating the women with respect, and (d) delivering compassionate care [23]. Thus collectively, effective communication from the provider to the patient improves patient’s trust, engagement and adherence which may ultimately lead to improved perinatal outcomes and reduce maternal mortality.

Conclusion

Maternal mortality is a growing problem in the United States. Black maternal mortality is 4x higher and is a public health crisis. It is a problem for Black American women and cannot be explained by socioeconomic factors alone. Reducing black maternal mortality involves a multi-tiered approach involving the patient, provider and public health policy. Black pregnant patients should be educated about optimizing their comorbidities prior to pregnancy and understand that pregnancy complications can translate to future cardiovascular health risks. Obstetric providers should educate primary health providers that pregnancy complications, such as preeclampsia and gestational diabetes, are associated with cardiovascular complications such as Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus, chronic hypertension, metabolic syndrome and stroke [24]. Obstetric providers can engage black patients with respect, providing continuity of care and compassion while delivering care. Public policy can ensure that black patients who suffer pregnancy related complications that are linked to adverse long-term cardiovascular health receive life-long coverage.

Acknowledgement

None.

Conflict of Interest

Authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Davis MB, Walsh MN (2019) Cardio-Obstetrics. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes 12(2): e005417.

- Cha S (2017) The impact of the worldwide Millennium Development Goals campaign on maternal and under-five child mortality reduction: 'Where did the worldwide campaign work most effectively?’ Glob Health Action 10(1): 1267961.

- Cantwell R, Clutton-Brock T, Cooper G, Dawson A, Drife J, et al. (2011) Saving Mothers' Lives: Reviewing maternal deaths to make motherhood safer: 2006-2008. The Eighth Report of the Confidential Enquiries into Maternal Deaths in the United Kingdom. BJOG 118 Suppl 1: 1-203.

- Sachs JD (2012) From millennium development goals to sustainable development goals. Lancet 379: 2206-2211.

- MacDorman MF, Declercq E, Cabral H, Morton C (2016) Recent Increases in the U.S. Maternal Mortality Rate: Disentangling Trends from Measurement Issues. Obstet Gynecol 128(3): 447-455.

- (2018) Notice of Retraction and Replacement: "Health Care Disparity and State-Specific Pregnancy-Related Mortality in the United States, 2005-2014" (Moaddab A, Dildy GA, Brown HL, Bateni ZH, Belfort MA, Sangi-Haghpeykar H, Clark SL) Obstet Gynecol 131(4): 746.

- Drife J (2016) Risk factors for maternal death revisited. BJOG 123(10): 1663.

- Brown HL, Chireau MV, Jallah Y, Howard D (2007) The "Hispanic paradox": an investigation of racial disparity in pregnancy outcomes at a tertiary care medical center. Am J Obstet Gynecol 197(2): 197.

- Berg CJ, Callaghan WM, Syverson C, Henderson Z (2010) Pregnancy-related mortality in the United States, 1998 to 2005. Obstet Gynecol 116(6): 1302-1309.

- Howell EA, Egorova N, Balbierz A, Zeitlin J, Hebert PL (2016) Black-white differences in severe maternal morbidity and site of care. Am J Obstet Gynecol 214(1): 122.

- Salm Ward TC, Mazul M, Ngui EM, Bridgewater FD, Harley AE (2013) “You learn to go last": perceptions of prenatal care experiences among African-American women with limited incomes. Matern Child Health J 17(10): 1753-1759.

- (2008) Update on overall prevalence of major birth defects--Atlanta, Georgia, 1978-2005. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 57(1): 1-5.

- Goyal MK, Kuppermann N, Cleary SD, Teach SJ, Chamberlain JM (2015) Racial Disparities in Pain Management of Children with Appendicitis in Emergency Departments. JAMA pediatrics 169(11): 996-1002.

- Cohan D (2019) Racist Like Me - A Call to Self-Reflection and Action for White Physicians. N Engl J Med 380(9): 805-807.

- Miller S, Belizán JM (2015) The true cost of maternal death: individual tragedy impacts family, community and nations. Reprod Health 12: 56.

- Molla M, Mitiku I, Worku A, Yamin AE (2015) Impacts of maternal mortality on living children and families: A qualitative study from Butajira, Ethiopia. Reproductive health 12 (Suppl 1): S6.

- Jones EJ, Hernandez TL, Edmonds JK, Ferranti EP (2019) Continued Disparities in Postpartum Follow-Up and Screening Among Women with Gestational Diabetes and Hypertensive Disorders of Pregnancy: A Systematic Review. J Perinat Neonatal Nurs 33(2): 136-148.

- Stasenko M, Cheng YW, McLean T, Jelin AC, Rand L, et al. (2010) Postpartum follow-up for women with gestational diabetes mellitus. Am J Perinatol 27(9): 737-742.

- McCloskey L, Bernstein J, Winter M, Iverson R, Lee-Parritz A (2014) Follow-up of gestational diabetes mellitus in an urban safety net hospital: missed opportunities to launch preventive care for women. J Womens Health (Larchmt) 23(4): 327-334.

- Graves CR, Davis SF (2018) Cardiovascular Complications in Pregnancy: It Is Time for Action. Circulation 137(12): 1213-1215.

- Thomas SB, Quinn SC (1991) The Tuskegee Syphilis Study, 1932 to 1972: implications for HIV education and AIDS risk education programs in the black community. Am J Public Health 81(11): 1498-1505.

- Dahlem CH, Villarruel AM, Ronis DL (2015) African American women and prenatal care: perceptions of patient-provider interaction. West J Nurs Res 37(2): 217-235.

- Lori JR, Yi CH, Martyn KK (2011) Provider characteristics desired by African American women in prenatal care. J Transcult Nurs 22(1): 71-76.

- Mounier-Vehier C, Madika AL, Boudghene-Stambouli F, Ledieu G, Delsart P, et al. (2016) [Hypertension in pregnancy and future maternal health]. Presse Med 45 (7-8 Pt 1): 659-666.

-

Rolanda L Lister, Wonder Drake, Scott Baldwin H, Cornelia Graves. Black Maternal Mortality-The Elephant in the Room. W J Gynecol Women’s Health. 3(1): 2019. WJGWH.MS.ID.000555.

Maternal Mortality, Blacks, Whites, Preconception, Maternal comorbidities, Pregnancy, Cesarean delivery, Racism, Preeclampsia, Gestational diabetes

-

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.