Research Article

Research Article

The Relationship Between Healthy Lifestyle and Menstrual Symptoms: A Study on University Students

Vasviye EROĞLU1*, Ayşe ÇATALOLUK2 and Dilara ARSLAN3

1Assistant Professor, Tokat Gaziosmanpasa University Faculty of Health Sciences, Department of Midwifery, Tokat, Turkey

2Assistant Professor, Assistant Professor, Tokat Gaziosmanpasa, University Faculty of Health Sciences, Department of Midwifery, Tokat, Turkey

3Midwife, Bachelor’s Degree, Tokat Gaziosmanpasa University Faculty of Health Sciences Midwifery Department, Turkey

Vasviye EROĞLU, Assistant Professor, Tokat Gaziosmanpasa University Faculty of Health Sciences, Department of Midwifery, Tokat, Turkey.

Received Date:July 13, 2025; Published Date:August 06, 2025

Abstract

Objectives: This study evaluated the relationship between university students’ healthy lifestyle beliefs and menstrual symptoms.

Methods: This cross-sectional, descriptive study was conducted between 05.03.2025 and 05.04.2025 with 231 female students studying at a

public university who agreed to participate in the study. Data were obtained through the “Personal Information Form”, “Healthy Lifestyle Belief Scale for Adolescents” and “Menstruation Symptom Scale”.

Results: 64.4% of the students, whose average age is 21.67±2.83, live in dormitories and 73.6% of their income is equal to their expenses. The mean age of first menarche was 13.11±1.23, 74.5% of the students reported that their menstruation was regular, 53.2% experienced pain every

month, and 51.1% reported that at least one of their family members had menstrual complaints. In the study, the mean score of the students on

the Healthy Lifestyle Belief Scale for Adolescents was determined as 64.96±10.02, and the total mean score of the Menstrual Symptom Scale was

determined as 73.03±18.59. A significant relationship was found between experiencing pain during menstruation, its severity, receiving treatment

for pain, and the Menstrual Symptom Scale scores. There was a weak negative significant relationship between the total score of the Healthy Lifestyle Belief Scale for Adolescents and the total score of the Menstrual Symptoms Scale. As the healthy lifestyle of the students increases, menstrual symptoms decrease. It was determined that experiencing pain during menstruation and its severity had a positive effect on the students’ menstrual symptoms, while a healthy lifestyle had a negative effect.

Conclusion: Menstrual symptoms are experienced less in young people who develop a healthy lifestyle. In this context, it is important for

midwives, who are advocates of women’s health, to provide consultancy services in developing healthy lifestyle behaviors.

Keywords: Healthy lifestyle; Menstrual symptoms; Menstruation

Introduction

Women’s health is a holistic health field influenced not only by biological factors but also by numerous psychological and social factors. Approximately half of women’s lives are spent with menstruation and its associated symptoms. Although menstruation is a physiological event, the physical and emotional symptoms experienced during this period can negatively impact individuals’ daily activities and increase their rate of seeking healthcare services [1]. The frequency and severity of menstrual symptoms, especially in young women, are closely related to the individual’s lifestyle habits [2]. Furthermore, the prevalence of menstrual symptoms varies according to age, social status, comorbidities, and medical history [3,4]. Menstrual symptoms; It manifests itself with various physical and psychological symptoms such as abdominal pain, headache, nausea, insomnia, fatigue, anxiety, depression, weakness, and diarrhea [5,6]. Symptoms experienced during the menstrual period can negatively affect women’s physical and psychological health [7]. In addition to physical and psychological health, it disrupts women’s quality of life, productivity, and sleep patterns, causing high rates of school and work absenteeism, limitations in activities, and a decrease in academic achievement [8,9]. Considering its prevalence and its effects on women’s daily activities, it is an extremely important problem for public health [10]. During their reproductive years, 80% of women experience at least one menstrual symptom, and 5% require symptom management, primarily pharmacological treatment, for pain control [11,12]. However, considering the side effects of pharmacological treatments and the long-term benefits of adopting healthy lifestyle behaviors, it has been reported that adopting a healthy lifestyle is more effective in managing menstrual symptoms and reducing their severity [13].

A healthy lifestyle is defined as a lifestyle that aims to prevent disease and improve health [14]. It encompasses multidimensional behaviors such as adequate and balanced nutrition, regular physical activity, stress management, sleep patterns, and avoiding harmful habits. These behaviors contribute to an individual’s physiological well-being and play an important role in regulating hormonal cycles and alleviating menstrual symptoms [15]. During the university years, which mark the transition from adolescence to adulthood, self-care behaviors develop. Developing healthy lifestyle behaviors during this period will contribute to a reduction in disease burden and an improved quality of life during adulthood. Adopting a healthy lifestyle alleviates menstrual symptoms and minimizes discomfort [16]. No studies demonstrating the relationship between healthy lifestyle behaviors and menstrual symptoms were found in the literature to determine the training and counseling programs to be provided in this direction. Therefore, this study aimed to determine the relationship between healthy lifestyle behaviors and menstrual symptoms in university students.

Materials and Methods

Research design and sampling

This descriptive, cross-sectional, and correlational study was conducted at a public university between March 5 and April 5, 2025. The study population consisted of students between the ages of 17 and 24 studying at the university. The study sample consisted of 231 women between the ages of 17 and 24 who volunteered to participate in the study and completed the data collection forms completely.

Data collection tools

Data were collected using a Personal Information Form, the Healthy Lifestyle Beliefs Scale for Adolescents, and the Menstrual Symptom Questionnaire (MSQ).

Personal information form: This form was developed by the researchers based on a literature review. It included 13 questions regarding the students’ age, education, income, and menstrual characteristics [17,18].

Healthy lifestyle beliefs scale for adolescents: The scale was developed by Kudubes and Bektas in 2020 and is a five-point Likert-type scale (1= strongly disagree, 2= disagree, 3= undecided, 4= agree, 5= strongly agree). The minimum score possible from the scale is 16 and the maximum is 80. An increase in the score indicates an individual’s healthy lifestyle beliefs. The scale consists of 16 items and three sub-dimensions. Items 4, 5, 6, 11, 12, 13, and 16 of the scale constitute the health belief sub-dimension, items 2, 7, 9, 14, and 15 constitute the physical activity sub-dimension, and items 1, 3, 8, and 10 constitute the nutrition sub-dimension. The Cronbach’s alpha coefficient for the scale is 0.90, and the Cronbach’s alpha values for the subscales are 0.79, 0.84, and 0.81 [19]. In our study, the Cronbach’s alpha values for the scale were calculated as 0.88, and the Cronbach’s alpha values for the subscales were 0.87, 0.87, and 0.81.

MSQ: The MSQ was developed by Chesney and Tasto in 1975 to assess menstrual pain and symptoms. The Turkish validity and reliability of the scale was conducted by Güvenç et al. in 2014. The score of the 22-item, five-point Likert-type scale is calculated by assigning a score between 1 (never) and 5 (always) to menstruationrelated symptoms. Items 1-13 belong to the “Negative affect/ somatic complaints” subscale, items 14-19 belong to the “Menstrual pain symptoms” subscale, and items 20-22 belong to the “Coping methods” subscale. The subscale score is calculated by averaging the total scores of the items in the subscales. Higher subscale scores indicate greater severity of menstrual symptoms related to that subscale. The scale’s Cronbach’s alpha is 0.92 [20]. In our study, the scale’s Cronbach’s alpha was calculated as 0.94.

Data collection and analysis

Data were collected using QR codes and Google Forms after the study was explained to university students at their convenience during the study period, and their verbal consent was obtained. Participants were asked to scan the QR code on the scale forms on their phones, read and complete the informed consent forms, and then complete the Personal Information Form, the Healthy Lifestyle Beliefs Scale for Adolescents, and the MSQ forms. This method was used in person to avoid paper waste. Data obtained from the study were analyzed using the IBM SPSS 22.0 software package. Data were analyzed using descriptive statistics such as number, percentage, mean±standard deviation, minimum and maximum values, t-test, One-Way ANOVA (Tukey’s test for posthoc analysis), Kruskal-Wallis H test, and Mann-Whitney U test, correlation and regression analysis.

Ethical aspects of the study

Before beginning the study, ethics committee approval was obtained from the University’s Social and Human Sciences Ethics Committee (Date: 05/03/2025, No: 04.15), and informed consent was obtained from the students before the forms were administered. The Declaration of Helsinki Principles was adhered to at all stages of the research.

Results

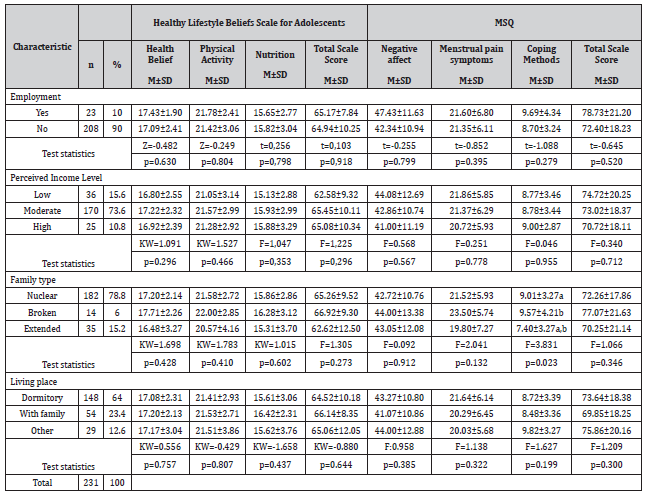

Of the students whose mean age was 21.67±2.83 (17-24), 64.4% lived in dormitories, and 73.6% had income equal to their expenses. Among young women whose mean age at menarche was 13.11±1.23, 74.5% reported regular menstruation, 53.2% experienced monthly pain, and 54.1% reported unbearable menstrual pain. When the distribution of mean scores on the Healthy Lifestyle Beliefs Scale for Adolescents and the MSQ was examined according to the participants’ sociodemographic characteristics, a significant difference was found between the MSQ Coping Methods subscale for family structure (p<0.05), and no significant difference was found between the other variables and the scores on either scale (p>0.05) (Table 1).

Table 1: Comparison of Adolescents’ Healthy Lifestyle Beliefs Scale for Adolescents and MSQ Total and Subscale Scores by Sociodemographic Characteristics (N=231).

M: Mean, SD: Standard Deviation, t: Independent sample t test, F: One Way ANOVA (Tukey test in posthoc analysis), KW: Kruskal Wallis H test, Z: Mann Whitney U test, a, b, c: there is a significant difference between groups with the same letter.

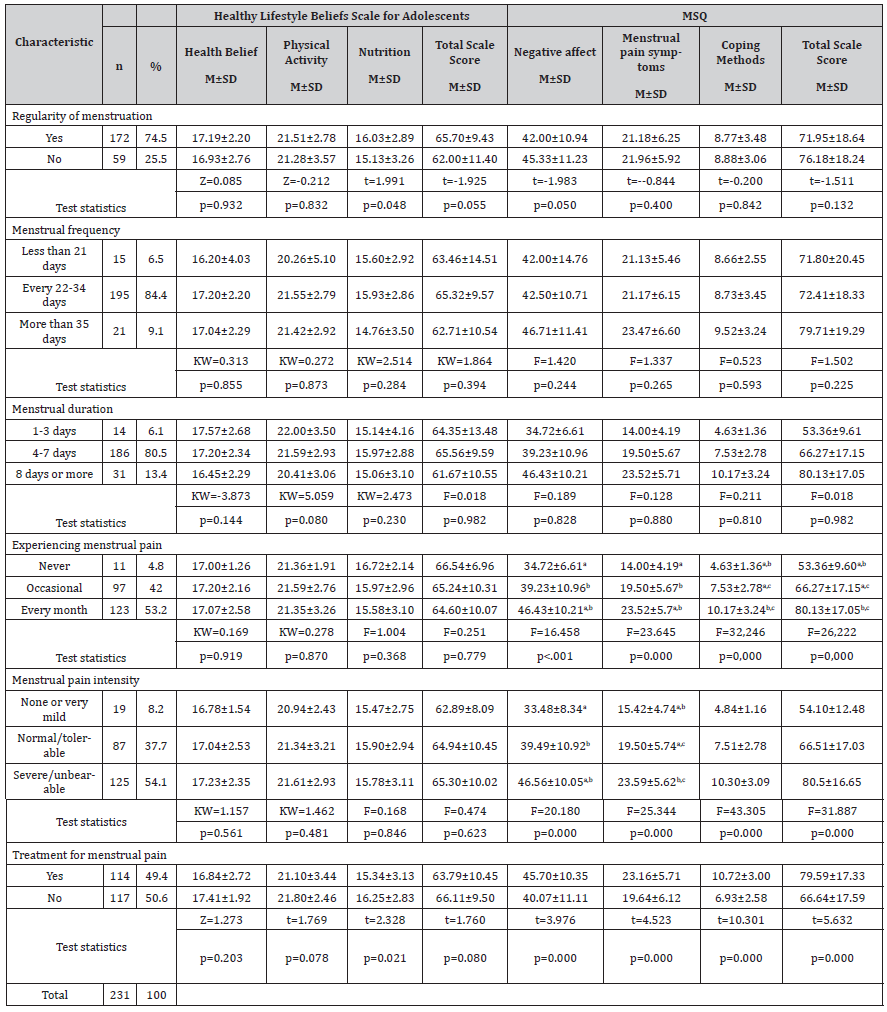

Of the students, 74.5% reported regular menstruation, 84.4% reported menstruation every 22-34 days, 80.5% reported menstruation lasting 4-7 days, 53.2% experienced pain every month, 54.1% reported severe/unbearable menstrual pain, and 50.6% reported receiving treatment for menstrual pain. When the distribution of mean scores on the Healthy Lifestyle Beliefs Scale for Adolescents and MSQ was examined according to participants’ menstrual characteristics, it was found that there were significant differences between menstrual regularity and treatment for menstrual pain and the Nutrition subscale of the Healthy Lifestyle Beliefs Scale for Adolescents; between experiencing pain during the menstrual period, pain severity, and treatment for pain, and the MSQ total and all subscales; but there were no significant differences between other variables and both scale scores (Table 2).

Table 2: Comparison of participants’ menstrual characteristics with the total and sub-dimension scores of the Healthy Lifestyle Beliefs Scale for Adolescents and MSQ (N=231).

M: Mean, SD: Standard Deviation, t: Independent sample t test, F: One Way ANOVA (Tukey test in posthoc analysis), KW: Kruskal Wallis H test, Z: Mann Whitney U test, a, b, c: there is a significant difference between groups with the same letter.

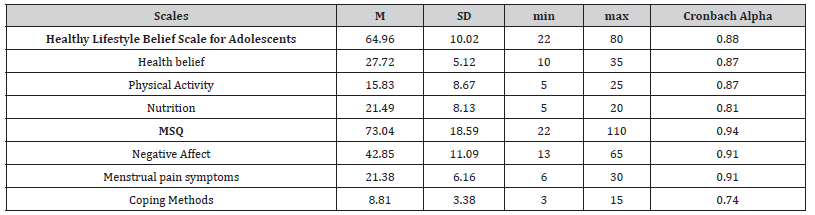

Cronbach’s Alpha reliability coefficients for the Healthy Lifestyle Beliefs Scale for Adolescents and MSQ are shown in Table 3. When the total and sub-dimension mean scores of the Healthy Lifestyle Beliefs Scale for Adolescents were evaluated, it was found that the total mean score was 64.69±10.02; the “Health Belief” sub-dimension mean score was 22.72±5.12; the “Physical Activity” sub-dimension mean score was 15.83±8.67 and the “Nutrition” sub-dimension mean score was 21.49±8.13. When the total and sub-dimension mean scores of the MSQ were evaluated, the total mean score was 73.04±18.59; the “Negative affect” sub-dimension mean score was 42.85±11.09; the “menstrual pain symptoms” sub-dimension mean score was 21.38±6.16; The mean score of the “Coping Methods” sub-dimension was found to be 8.81±3.38 (Table 3).

Table 3: Distribution of participants’ mean total and sub-dimension scores of the Healthy Lifestyle Beliefs Scale for Adolescents and MSQ (N=231).

M: Mean, SD: Standard Deviation

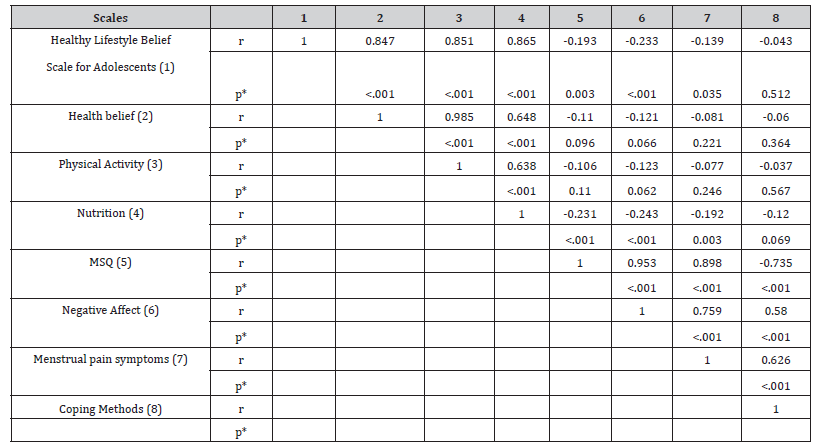

When the relationship between the Healthy Lifestyle Beliefs Scale for Adolescents and the MSQ total and subscales was evaluated, a negative, statistically significant, but small-scale relationship was determined between the Healthy Lifestyle Beliefs Scale for Adolescents and the MSQ (r=0.193; p=0.003). It was found that as the healthy lifestyle of young women increased, menstrual symptoms decreased (Table 4).

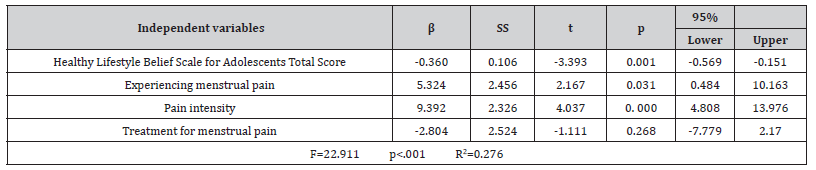

According to the multiple linear regression analysis conducted in the study, some variables were determined to have significant effects on young women’s menstrual symptoms. The model was found to be statistically significant (p<0.001) and the explanatory power was 27.6% (R²=0.276). This indicates that the independent variables included in the model (healthy lifestyle score, experiencing pain during menstruation, and pain intensity) explained approximately one-third of the variance in menstrual symptom levels. Accordingly, experiencing pain during menstruation and pain intensity positively and significantly affect menstrual symptoms. In other words, increases in these variables lead to increases in MSQ scores. This finding suggests that individuals experiencing pain during menstruation experience more physical and emotional symptoms. Conversely, an increase in the Healthy Lifestyle Beliefs Scale for Adolescents score is associated with a significant and negative change in menstrual symptom scores. This finding indicates that individuals who adopt healthy lifestyle behaviors experience menstruation-related symptoms less severely (Table 5).

Table 4:The relationship between the Healthy Lifestyle Belief Scale for Adolescents and the MSQ total and subscales.

*Pearson correlation analysis

Table 5:Regression analysis of variables thought to be effective on menstrual symptoms.

Discussion

The findings of this study reveal that students’ beliefs about a healthy lifestyle and the severity of their menstrual symptoms were generally moderate to high. The students’ total mean score on the Healthy Lifestyle Belief Scale for Adolescents was 64.69±10.02, indicating that young women have a certain awareness of implementing healthy lifestyle behaviors. In a similar study using the same measurement tool, the mean score on the Healthy Lifestyle Belief Scale for Adolescents was reported as 59.13 [21]. According to the Healthy Lifestyle Behaviors Model developed by Walker, et al. (1987), as reported by Korkut Owen F, et al. [22] individuals’ health beliefs significantly influence the level of implementation of these behaviors. In addition, the significant correlation between the nutrition subscale and menstrual cycle and pain medication intake suggests that healthy nutrition may have positive effects on menstrual cycle and pain management. These findings support studies showing that eating habits are related to the level of dysmenorrhea [23,24].

The mean total MSQ score in the study was 73.04±18.59, and the highest subscale was Negative Effects (42.85±11.09), indicating that menstrual symptoms have negative effects on young women’s quality of life. These data support the conclusion in the study conducted by Aksoy Derya, et al. [25] that quality of life decreases as the severity of menstrual symptoms increases. On the other hand, the finding of a significant relationship between family structure and the “Coping Methods” subscale suggests the impact of social support and lifestyle on symptom management. The greater prominence of individual coping strategies, especially in nuclear families, suggests that social support is effective in coping methods. These data support studies reporting that premenstrual syndrome is associated with family relationships and social support [26,27]. In the study, more than half of the young women reported experiencing pain during menstruation, that this pain was unbearable, and that they sought treatment. Similarly, Bilgin Z [18] found that more than half of the young women experienced these conditions. Furthermore, the strong correlations between menstrual pain intensity, pain experience, and treatment seeking in the total and subscales of the MSQ indicate that the physical and psychological effects of dysmenorrhea should be evaluated holistically. Significant differences were observed between the rates of medication use among individuals experiencing pain, indicating that treatment seeking parallels symptom intensity. This study demonstrates that healthy lifestyle beliefs and coping strategies for menstrual symptoms are influenced by individual, social, and physiological variables.

The current study found that menstrual symptoms decreased as students’ healthy lifestyles increased. This relationship is strongly supported in the literature. A study conducted in Iran found that the severity of dysmenorrhea was significantly lower in young women with high scores on health-supportive nutrition and regular physical activity. The same research shows that healthy lifestyle habits reduce the duration and severity of symptoms [28]. Furthermore, a study conducted in Spain found that both the prevalence of dysmenorrhea and the severity of symptoms were significantly lower in women who followed healthy eating habits, such as the Mediterranean diet [29]. Furthermore, a meta-analysis reported that low- or moderate-intensity exercise three times a week reduced the intensity of menstrual pain. Exercise-induced endorphin release, increased pelvic circulation, and reduced stress have been implicated as the primary mechanisms of this effect [30].

Regression analysis showed a significant relationship between menstrual symptom severity, menstrual pain frequency and intensity, and healthy lifestyle beliefs (Total score of the Healthy Lifestyle Belief Scale for Adolescents). This model explained 27.6% of the variance in symptom levels (p<0.05). Similarly, in regression analyses conducted on young women in Mexico, variables such as pain duration and intensity were identified as strong predictors that could significantly predict menstrual symptom scores (R²≈0.45) [31]. In an analysis conducted on adolescent female students in Iran, healthy lifestyle dimensions such as nutrition (β= –0.18, p<0.001) and exercise (β = –0.17, p<0.001) were found to significantly reduce dysmenorrhea pain severity [28]. Additionally, in Spain, low adherence to the Mediterranean diet was positively associated with increased menstrual symptoms (OR≈1.47), and physical inactivity was positively associated with premenstrual symptom scores [32]. The explanatory power of the model in this study was found to be 27.6%. This study model explained R² = 27.6% of the variance, while the Iranian study showed higher R² levels of ~0.08–0.10 and the Mexican study showed higher R²˃0.45. These differences are thought to be due to the scale used, sample size, and the number of variables included in the model. However, an explanatory power level of ≥20% is generally considered a strong model with clinical significance.

Conclusion

The findings of this study revealed significant relationships between subcomponents of students’ healthy lifestyle beliefs, particularly nutrition, physical activity, and health beliefs, and menstrual symptom management. These findings demonstrate that young students’ lifestyle choices can directly impact their menstrual health. It is understood that coping strategies for menstrual pain and symptoms are shaped by an individual’s social environment and living conditions. Therefore, it is recommended that health education and counseling programs for young university students focus on both supporting healthy lifestyle behaviors and developing effective coping skills for menstrual symptoms. Furthermore, expanding awareness of menstrual health and facilitating access to treatment can significantly contribute to improving individual wellbeing.

Acknowledgement

None.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Öztürk R, Güneri SE (2021) Symptoms experiences and attitudes towards menstruation among adolescent girls. J Obstet Gynaecol 41(3): 471-476.

- Sharma P, Patro A, Ibrahim ST, SKR Jain N, Mallya SD (2018) Premenstrual symptoms and lifestyle factors associated with it among medical students. Indian Journal of Public Health Research and Development 9(10): 39-45.

- Mitsuhashi R, Sawai A, Kiyohara K, Shiraki H, Nakata Y (2023) Factors Associated with the Prevalence and Severity of Menstrual Related Symptoms: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Int J Environ Res Public Health 20(1): 569.

- Shimamoto K, Hirano M, Wada Hiraike O, Goto R, Osuga Y (2021) Examining the association between menstrual symptoms and health related quality of life among working women in Japan using the EQ 5D. BMC Women’s Health 21(1): 325.

- Naraoka Y, Hosokawa M, Minato Inokawa S, Sato Y (2023) Severity of Menstrual Pain Is Associated with Nutritional Intake and Lifestyle Habits. Healthcare (Switzerland) 11(9): 1289.

- Yoshino O, Takahashi N, Suzukamo Y (2022) Menstrual Symptoms, Health Related Quality of Life, and Work Productivity in Japanese Women with Dysmenorrhea Receiving Different Treatments: Prospective Observational Study. Adv Ther 39(6): 2562-2577.

- Dhar S, Mondal KK, Bhattacharjee P (2023) Influence of lifestyle factors with the outcome of menstrual disorders among adolescents and young women in West Bengal, India. Sci Rep 13(1): 12476.

- Saji A, Sunil KA, John AM, B, AK, Thomas AA (2021) Prevelance of symptoms during menstruation and its management among adolescent girls. International Journal of Community Medicine And Public Health 8(9): 4325.

- Tassyabela FM, Sunarto S, Sulikah S, Surtinah N (2024) Coping Mechanisms among Women Who Experience Dysmenorrhea in Baleasri Village, Magetan, Indonesia. Health Dynamics 1(10): 353-360.

- Tahir A, Naseer B, Shafaq F (2025) Perception of university students about the use of painkillers, other remedies and lifestyle modifications for primary dysmenorrhea; a cross sectional study at KEMU. BMC Women’s Health 25(1): 4-11.

- Akkuş Uçar M (2024) Düzenli egzersizin menstrüasyon semptomları üzerine etkisinin araştırılması. Gümüşhane Üniversitesi Sağlık Bilimleri Dergisi 13(1): 392-399.

- Aziato L, Dedey F, Clegg Lamptey JNA (2015) Dysmenorrhea management and coping among students in Ghana: A qualitative exploration. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol 28(3): 163-169.

- Itani R, Soubra L, Karout S, Rahme D, Karout L, et al. (2022) Primary Dysmenorrhea: Pathophysiology, Diagnosis, and Treatment Updates. Korean J Fam Med 43(2): 101-108.

- Mamurov B, Mamanazarov A, Abdullaev K, Davronov I, Davronov N, Kobiljonov K (2020) Acmeological Approach to the Formation of Healthy Lifestyle Among University Students 129: 347-353.

- Öztürk S, Karaca A (2019) Premenstruel sendrom ve sağlıklı yaşam biçimi davranışlarına ilişkin ebe ve hemşirenin rolü. Balıkesir Sağlık Bilimleri Dergisi 8(2): 105-110.

- Ridzuan AR bin, Karim RA, Marmaya NH, Razak NA, Khalid NKN, et al. (2018) Public Awareness towards Healthy Lifestyle. International Journal of Academic Research in Business and Social Sciences 8(10).

- Şimşek D, Duman FN, Gölbaşı Z (2022) Sağlık bilimleri fakültesi öğrencilerinin premenstrual sendrom ile baş etmede kullandığı geleneksel ve tamamlayıcı tıp uygulamaları. Mersin Üniversitesi Tıp Fakültesi Lokman Hekim Tıp Tarihi ve Folklorik Tıp Dergisi 12(1): 116–125.

- Bilgin Z (2023) Dismenore durumuna göre genç kadınların menstrüel profilleri ve anksiyete düze Süleyman Demirel Üniversitesi Sağlık Bilimleri Dergisi 14(2): 111–121.

- Kudubeş AA, Bektas M (2020) Psychometric properties of the Turkish version of The Healthy Lifestyle Belief Scale for Adolescents. J Pediatr Nurs 53: e57 e63.

- Güvenç G, Seven M, Akyüz A (2014) Menstrüasyon Semptom Ölçeği’nin Türkçe'ye uyarlanması, TAF Preventive Medicine Bulletin 13(5): 367 374.

- Durak Y, Karayağız Muslu G (2023) Adölesanların sağlıklı yaşam tarzı inançları ile sürdürülebilir yaşama yönelik farkındalıkları Arasındaki İlişkinin İncelenmesi. UNIKA Journal of Health Sciences 3(3): 588-600.

- Korkut Owen F, Demirbaş Çelik N (2018) Yaşam Boyu Sağlıklı Yaşam ve İyilik Hali. Psikiyatride Güncel Yaklaşımlar 10(4): 440–453.

- Aktaş D, Külcü Polat D, Şahin E (2023) The relationships between primary dysmenorrhea with body mass index and nutritional habits in young women. Journal of Education and Research in Nursing 20(2): 143-149.

- Kartal YA, Akyuz EY (2018) The effect of diet on primary dysmenorrhea in university students: A randomized controlled clinical trial. Pak J Med Sci 34(6): 1478-1482.

- Aksoy Derya Y, Erdemoğlu Ç, Özşahin Z. (2019) Üniversite öğrencilerinde menstrual semptom yaşama durumu ve yaşam kalitesine etkisi. Acibadem Universitesi Saglik Bilimleri Dergisi 10(2): 176–181.

- Upadhya S (2025) Menstrual health: Family support and household practices among bachelor level female students. KMC Journal 7(1): 325–340.

- Tekbaş S, Sarpkaya Güder D (2024) Prevalence of premenstrual syndrome and methods of coping with the symptoms in nursing students. Journal of Academic Research in Nursing 10(2): 138-145.

- Cholbeigi E, Rezaienik S, Safari N, Lissack K, Griffiths MD, et al. (2022) Are health promoting lifestyles associated with pain intensity and menstrual distress among Iranian adolescent girls? BMC Pediatr 22(1): 574.

- Onieva Zafra MD, Fernández Martínez E, Abreu Sánchez A, Iglesias López MT, García Padilla FM, et al. (2020) Relationship between diet, menstrual pain and other menstrual characteristics among Spanish students. Nutrients 12(6): 1759.

- Cai J, Liu M, Jing Y, Yin Z, Kong N, et al. (2025) Aerobic exercise to alleviate primary dysmenorrhea in adolescents and young women: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 104(5): 815-828.

- Alatorre Cruz JM, Alatorre Cruz GC, Marín Cevada V, Carreño López R (2024) Dysmenorrhea and Premenstrual Syndrome in Association with Health Habits in the Mexican Population: A Cross Sectional Study. Healthcare (Basel) 12(21): 2174.

- Franco Antonio C, Santano Mogena E, Cordovilla Guardia S (2025) Dysmenorrhea, premenstrual syndrome, and lifestyle habits in young university students in Spain: A cross sectional study. J Nurs Res 33(1): e374.

-

Vasviye EROĞLU*, Ayşe ÇATALOLUK and Dilara ARSLAN. The Relationship Between Healthy Lifestyle and Menstrual Symptoms: A Study on University Students. W J Gynecol Women’s Health. 6(5): 2025. WJGWH.MS.ID.000646.

Healthy lifestyle, Menstrual symptoms, Menstruation

-

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.