Research Article

Research Article

Diagnose and Management of Molar Pregnancy at N’Djamena Chadian and Chinese Friendship University Hospital

Mahamat AC1, Gabkika BM1,2*, Aché H1, Mihimit A3, Nemian M1, Brahim D4, Zeinab D4 and Foumsou L1,2

1University of N’Djamena, Faculty of Human Health Sciences, Chad

2University Hospital Center for Mother and Child, Chad

3Adam Barka University of Abéché, Faculty of Human Health Sciences, Chad

4N’Djamena Chadian and Chinese friendship university hospital, Chad

Gabkika Bray Madoué, Department of Gynecology and Obstetrics, N‘Djamena Mother and Child University Hospital, Chad.

Received Date:March 03, 2025; Published Date:June 09, 2025

Abstract

Introduction: Hydatidiform mole or molar pregnancy is a cystic degeneration of the chorionic villi associated with tumor proliferation of the trophoblast.

Objective: Contribute to the management of hydatidiform mole pregnancy.

Patients and Methods: This was a descriptive study with prospective data performed in the obstetrics and gynecology department of

gynecology and obstetrics of N’Djamena Chadian and Chinese Friendship University Hospital.

Studied population consisted of all patients admitted to the gynecological-obstetric emergency department for first-trimester hemorrhage. All

patients admitted for a molar pregnancy and consenting patients were included in the study.

Data were collected using a pre-established data sheet containing all the variables. Patients were retained and followed throughout the study

period.

Studied variables were clinical, paraclinical and prognostic. Data were entered using Excel and analyzed using SPSS version 26.

Results: The frequency of molar pregnancies was 0.85%. The most common age group was 15 to 20. The mean age was 25.15 years, with

extremes of 15 and 40 years. The main reason for consultation was metrorrhagia in 57.5% of cases, with a uterus larger than the gestational age on

examination (80%). Beta HCG was performed prior to aspiration in 87% of patients.

All patients (100%) had had a shape describe as honeycomb during the ultrasound, luteal cysts were detected in 78% of cases. The histological

examination was performed in 100% of cases aiming to confirm the diagnosis. Management consisted of manual intrauterine aspiration in most

cases (75%).

Post-molar surveillance was carried out over a 2-year period, with 80% of cases lost to follow-up at 12 months and 86.3% at 24 months.

The prognosis was marked by the occurrence of 5% choriocarcinoma and 1.2% maternal death.

Conclusion: Hydatidiform mole is a relatively common condition. Post-molar surveillance is hampered by several factors in our context.

Keywords:Molar pregnancy; Monitoring; Prognosis; CHU-ATC; N’Djamena

Introduction

Hydatidiform mole (HM) is defined as partial or total hydropic degeneration of the chorionic villi with more or less marked proliferation of trophoblastic cells. It is characterized by excessive secretion of chorionic gonadotropic hormone, the β-subunit of which is an important diagnostic and post-treatment monitoring method [1]. These moles appear as a result of the abnormal development of trophoblastic tissue.

The incidence of gestational trophoblastic disease (GTD) is influenced by ethnic origin and risk factors include age, family history, parity, personal history of hydatidiform mole and history of miscarriage [2].

Molar pregnancy is the most common trophoblastic disease. It has an incidence of 1-2/1000 in Europe and Asia [3]. Recent reports from the Republic of Korea and Japan show that the incidence of hydatidiform mole has become as low as in Europe or the United States [4] in Marrakech University Hospital, the reported was 4.34% of all pregnancies covering a period of five years [5].

It represents a public health problem in developing countries because of its high frequency. The existence of a specific biological marker, gonadotropic chorionic hormone (HCG), in addition to ultrasound imaging and histological examination, enables molar pregnancy to be diagnosed, monitored and an effective and appropriate treatment protocol to be established [6].

Once the diagnosis of complete or partial mole has been made by the triad (clinical, ultrasound and biological), and after assessment of the patient’s general and hemodynamic condition by the pretreatment preparation, uterine evacuation by aspiration can be perform [7]. If treated early, molar pregnancy progresses favorably, with 90% of moles recovering after uterine evacuation. However, complications are possible. These include molar abortion, which is always patchy and sometimes leads to severe anemia requiring blood transfusion in some cases, and malignant degeneration, which is responsible for maternal death in 6.25% of cases [8].

There are several monitoring schedules. The French College of Gynecology recommends weekly monitoring after aspiration [9]. However, for financial reasons, there is no protocol adapted to the disadvantaged mode. In the literature, it is recommended that gonadotropic chorionic hormone (GCH) levels should be measured on a weekly basis.

(HCG) every 15 days, after uterine evacuation and until negativation, then every month for 6 months and every 3 months for a year [10]. This monitoring is certainly necessary, but it has no direct influence on the natural course of the disease.

Patients and Method

This was a descriptive study with prospective data collection covering a period of 24-month period from 1st January 2022 to 30th December 2024, performed in the gynecology-obstetrics department of the N’Djamena Chadian and Chinese Friendship University Hospital.

Study population consisted of all patients admitted to the gynecological-obstetric emergency department for first-trimester hemorrhage during the study period.

All pregnant women admitted for a molar pregnancy, patients with a histologically confirmed diagnosis of molar pregnancy and consenting patients were included in the study.

Data were collected using a pre-established survey form containing all the variables. The data collection technique was direct interview with the patients. Some additional information was obtained by telephone. They were hiked one week after manual intrauterine aspiration, at 3 weeks, at 45 days, at 6 months until negativation. Then they were returned at 12 and 24 months [11]. At each visit, the patients were assessed for complications.

Studied variables were clinical, in particular gynecologyobstetric history (gesity, parity) and medical history, reason for consultation or referral (metrorrhagia, cough, vomiting....), macroscopic examination of the mole (vesicle or trophoblastic remaining)), state of the uterus, etc., and treatment (intra uterine aspiration). We used Word and EXCEL 2013 software for data entry and analyzed the data using SPSS version 26 software.

Results

Epidemiological characteristics

We recorded 80 cases of molar pregnancies among 9408 pregnancies, giving a frequency of 0.85%. The most common age group was 15 to 20, with 35% of cases. The average age was 23.5 years +/- 2.5 years, ranging from 15 to 40 years.

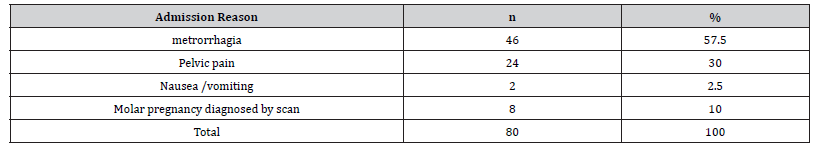

Reason for consultation

In 57.5% of cases, metrorrhagia was reason for admission (Table 1).

Table 1:Reason for admission.

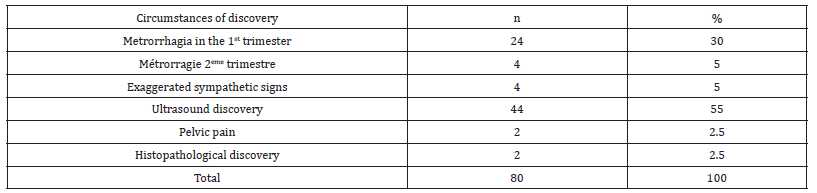

Circumstances of discovery.

All patients had claimed for amenorrhea.

Seventy-seven percent of patients had sought medical advice prior to the abortion.

Ultrasound was the most common reason for discovery (55%) (Table 2).

Table 2:Distribution of patients according to the reason for discovery.

Seventy-seven percent of patients had sought medical advice prior to the abortion. Ultrasound was the most common reason for discovery (55%).

Ultrasound findings

The uterus was larger than the gestational age in 80% of cases. Macroscopically, a vesicular appearance was found in almost three quarters of patients (72.5%). All patients had had a shape described as honeycomb during the ultrasound and a luteal cyst was accounted for 78%.

Management

Intra uterine manual aspiration was performed in most cases (75%). Most patients were transfused (60%). All patients (100%) had undergone histology to confirm the diagnosis. The majority of patients were hospitalized for less than 7 days (92%).

Surveillance

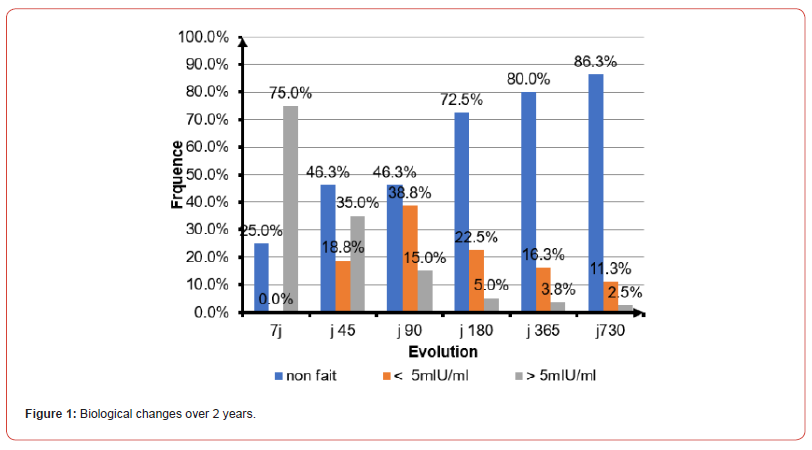

During surveillance, 80% of patients were lost to follow-up at 12 months and 86.3% at 24 months.

The course was marked by the occurrence of 4 cases of choriocarcinoma, i.e. 5%, of which 3 patients were undergoing polychemotherapy with a favorable outcome. We recorded 1.2% maternal deaths (Figure 1).

Discussion

We recorded a frequency of 0.85% of molar pregnancies during this study. This frequency is comparable to Mbala report in Kinshasa in 2017, which noted a frequency 0.13% (1 mole for 743 pregnancies) [11]. This higher frequency can be explained by the fact that the incidence of pregnancy varies from one region to another and from one era to another. Nevertheless, there is a predominance of mole in developing countries, linked for most authors to nutritional factors and poor socio-economic conditions [12]. For some of these authors, the nutritional factors that explain the occurrence of a mole pregnancy are linked to a deficiency in vitamin A (which plays an important role in the correct development of meiosis) and/or folates (vitamin B9), which are necessary for protein and DNA synthesis [12]. These deleterious factors are thought to come into play at the time of conception [12].

With regard to risk factors, in this series the patients were aged between 15 and 40 years, the most common age group was 15 to 20, with 35% of cases. Our results are comparable to those of Mahaman in Morocco in 2016, who found in his study a high frequency between for the age group of 21 and 25 years of age [13]. This result is inferior to Guido findings in Mali, who, reported a mean age of 32.4+/-10.6 years (extremes of 16 and 48 years). With the group of 15-20 and 45-50 age groups accounting for 18% [14].

The clinical aspects in this study was dominated by metrorrhagia in 87% , exacerbation of sympathetic signs of pregnancy (5%) and uterine height, which was greater than the presumed age of pregnancy in 80% of cases. Laaouini, et al. in Morocco in their study found a clinical presentation which is usually that of a threatened abortion or spontaneous miscarriage in the first trimester with metrorrhagia in more than 90% [15]. Sako in Mali in 2010 reported a uterine height greater than the presumed age of pregnancy in 73.9% of cases [16].The notion of amenorrhea was found in all patients (100%).According to the literature [17], the physical signs suggestive of molar pregnancy are metrorrhagia in the 1st trimester associated with a uterus too large for term.

If molar pregnancy is suspected, two additional tests should be carried out to confirm the diagnosis: pelvic ultrasound and plasma βHCG. In any case, ultrasound is the most important imaging tool for diagnosis [18]. The most frequently described ultrasound shape in this series was the honeycomb aspect found in 100% of cases. This rate is higher than that of Kouamé, et al. [17] in Côte d’Ivoire in 2019 who reported a multivesicular appearance in 68% and 8% of cysts. Boufettal, et al. in Morocco in 2011 [18], noted 87.5% of ‘snowstorm’ and ‘honeycomb’ images and 30.7% of cysts [18]. This difference in rates can be explained by the fact that the incidence of molar pregnancy varies from one region to another and from one period to another. Living conditions are often cited as risk factors in the medical literature, which explains the difference in the frequency of molar pregnancy in industrialized and developing countries [19]. In addition to ultrasound, plasma beta HCG measurement is the only test that can confirm the diagnosis. However, a positive result is not synonymous with a molar pregnancy. Rather, it is the fact that it is higher than the term of the pregnancy that is important. We found that plasma beta HCG was requested in all patients (100%). This rate is higher than that reported by Sacko K [16] and Guindo B in Mali in 2021, who respectively reported 84% and 86.4% of HCG tests [14].

Management consisted of uterine evacuation. The method of choice is ultrasound-guided endo-uterine aspiration with prevention of uterine hemorrhage by concomitant administration of utero-tonics [20,21]. In this series, 75% of patients underwent manual intrauterine aspiration.

These proportions corroborate those of Achille et al in Benin in 2019 [22] who reported 76.9% of treatment by manual intrauterine aspiration. However, it is lower than that reported by Tripti, et al. in India in 2024, who reported a rate of 93.5% of evacuation by aspiration [23].

Histologically, macroscopic examination of the moles revealed vesicles in 72.5% of cases and trophoblastic debris in 22.5%. This result is slightly lower than that of Sacko [16] in Mali in 2010, who reported 76.1% vesicles.

With regard to the evolution of the disease, we instituted surveillance based essentially on clinical and biological signs. In order to avoid any new pregnancies, we instituted contraception during monitoring. The frequency of monitoring was during the 1st week following treatment. At one week of monitoring, the βHCG level was greater than 5mlIU/l in 75% of cases; there were no cases of negativation and 25% of patients were lost to follow-up. This result is superior to that of Achille et al in Benin in 2019 [22] in 91 cases of hydatidiform mole, where only 9.9% of patients were able to comply with the plasma β-hCG assay until it became negative.

After 12 months, 90.1% of patients in this study had been lost to follow-up and 9.9% had been declared cured. After 24 months of monitoring, 13.7% of patients had tested negative for beta hcg, 11.2 of them; 1.25% had an elevated β-hCG value and 1.25% had died of choriocarcinoma.

In his study, Sacko [16] in Mali found a cure rate of 9%. The same observation was made by Dénakpo, et al. [24] in Benin in 2011 who found that out of 73 patients presenting with hydatidiform mole, the number of patients who had complied with biological monitoring by measuring plasma beta- hCG decreased from 10 to 1, one year after the mole; whereas only 4 patients had complied with the measurement of plasma β-hCG until they were negative.

These results show that post-mole monitoring poses a real problem in our context. This could be explained by the low socioeconomic status of most patients, their lack of information about the disease, and the socio-cultural constraints that are at the root of this situation.

Conclusion

The management of molar pregnancy is a routine activity at the Chad-China Friendship University Hospital. The main reason for consultation is metrorrhagia. Ultrasound and hCG assay are helpful in the diagnosis, indicating uterine evacuation, and histological study is essential.

The majority of cases have a favorable outcome, provided that regular monitoring is carried out and appropriate treatment is given to detect any abnormal resumption of trophoblastic activity.

Acknowledgement

None.

Conflict of Interest

Authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Galiou MR (2019) Molar pregnancy: management at the Orange Maternity Hospital. Rabat: Université Mohamed V.

- Horowitz NS, Eskander RN, Adelman MR, Burke W (2021) Epidemiology, diagnosis, and treatment of gestational trophoblastic disease: an evidence-based review and recommendation from the Society of Gynecologic Oncology. Gynecol Oncol 163(3): 605-613.

- Sophie Schoenen , Katty Delbecque, Anne-Sophie Van Rompuy, Etienne Marbaix, Jean-Christophe Noel, et al. (2022) Importance of pathological review of gestational trophoblastic diseases: results of the Belgian Gestational Trophoblastic Diseases Registry. Int J Gynecol Cancer 32(6): 740-745.

- Hexatan YS Ngan, Michael J, Seckl, Ross S, Berkowitz, et al. (2021) diagnosis and management of gestational trophoblastic diseases:update 2021; International Journal of Gynecology and Obstetrics 155: 86-90.

- K Laaouini, M Bendahhou Idrissi, K Saoud, N Mamouni, S Errarhay, et al. (2023) Recurrent hydatidiform mole. Journal of Medical and Dental Science Research 10(4): 49-52.

- Chelli D, Dimassik, Bouazizm, Ghaffaric, Zaouaouib, Sfare (2008) Imaging of gestational trophoblastic diseases .J Gynecol Obstet Biol Reprod 37: 559-567.

- Lenhart Megan MD (2007) Diagnosis and Treatment of Molar Pregnancy’, Postgraduate Obstetrics & Gynecology 27(17): 01-04.

- Koné KN (2019) Molar pregnancy in the gynecology and obstetrics department of the Gabriel Touré University Hospital: about 16 cases. [Thesis :medicine]. Bamako; University of Bamako.

- Diaouga HS, Yacouba MC, Garba RM, Oumara M, Lazare HL, et al. (2023) Invasive partial hydatidiform molar pregnancy with pulmonary and vaginal metastases: about a case. Ann Afr Med 16(4): e5402-e5408.

- Gerulath AH, Ehlen TG, Bessett P, Savoie R (2002) Gestational trophoblastic disease. J Obstet Gynecol Can 24(5): 434-446.

- Mbala NL, Menayamu ND, Mbanzulu PN (2017) Clinical and Paraclinical Aspects of Molar Pregnancy in Two Medical Formations of Kinshasa. Kis Med 7(2): 281-290.

- Candelier JJ (2015) The complete hydatidiform mole. Med Sci 31(10): 861-868.

- Mahaman MM (2016) Epidemiological study; Clinical and therapeutic treatment of molar pregnancy in the Department of Gynecology-Obstetrics 2 of the Hassane II University Hospital of FES in Morocco [Thesis: medicine]. FES: University of FES.

- Guindo B (2021) Epidemio-clinical study and prognosis of molar pregnancy in the obstetrics and gynecology department of the University Hospital Point G. [Thesis: medicine] Bamako: USTTB.

- Laaouini K, Bendahhou Idrissi M, Saoud K, Mamouni N, Errarhay S, et al. (2023) Recurrent hydatidiform mole. Journal of Medical and Dental Science Research 10(4): 46-52.

- Sacko K (2010) Molar pregnancy in the obstetric gynaecology department of the CHU-Gabriel Touré from 2003-2007. [Thesis of medicine] Bamako: Université de Bamako.

- Kouamé N'goran, Kouadio Kouamé Eric, Doukouré Brahima, Sétchéou Alihonou, Konan Anhum Nicaise, et al. (2019) Epidemiological-clinical and ultrasound profile of hydatidiform moles in Abidjan. Pan Afr Med J 33: 264-269.

- Boufettal H, Coullin P, Mahdaoui S, Noun M, Hermas S, et al. (2011) Complete hydatidiform moles in Morocco: epidemiological and clinical study. J Gynecol Obstet Biol Reprod 40(5): 419-429.

- TRAORE Ousmane, DIARRA Oumcoumba, KOUMA Alassane, KONADJI Labassou, DEMBELE Wappa, et al. (2022) Ultrasound aspects of the etiologies of hemorrhages in the first trimester of pregnancy in Bamako. African Journal of Medical Imaging 14(3): 231-237.

- JJC Rajaonarison, JM Rakotondraisoa, HA Andrianampy, JA Randriambelomanana, HR Andrianampanalinarivo (2015) Management of hydatidiform moles at the University Hospital of Gynecology and Obstetrics of Befelatanana, Antananarivo Rev med. Madag 5(1): 510-515.

- I Lazrak, H Ihssane, MA Babahabib, J Kouach, M Reda El Ochi, et al. (2014) Invasive and metastatic partial hydatidiform mole: about a case. Pan African Medical Journal 19: 175 -184

- Achille Awadé AO, Luc Brun, Vodouhe MV, Kabibou Salifou, Hounkponou Ahouingnan FMN, et al. (2019) Epidemiological, diagnostic, therapeutic and prognostic aspects of Hydatidiform Mole at CHUD/B Parakou-European Scientific Journal 15(12): 45-52.

- Tripti Singh, Richa Sharma , Aruna Patel , Kirti Singh (2024) To determine the incidence, risk factors, clinical presentations, diagnosis, treatment options and outcomes of molar pregnancy. Forum of obstetrics and gynecology 34: 2022-2026.

- Dénakpo JL, Aguèmon C, Lokossou A, Salifou K, Renin Perrin, Xavier (2011) Gestational trophoblastic disease in Benin: Results of the of 83 cases. Burkina Médical 15(2): 5-9.

-

Mahamat AC, Gabkika BM*, Aché H, Mihimit A, Nemian M,et.all. Diagnose and Management of Molar Pregnancy at N’Djamena Chadian and Chinese Friendship University Hospital. W J Gynecol Women’s Health. 6(4): 2025. WJGWH.MS.ID.000643.

Molar pregnancy, Monitoring, Prognosis, CHU-ATC, N’Djamena

-

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.