Review Article

Review Article

Uganda Agriculture Human Capacity Development: Organic 3.0 Agriculture Gap and Need Analysis

Ayodele A Otaiku*

Ph.D. Scholar Faculty of Social science, Department of Geography and Environmental Management, University of Port Harcourt, Choba, Port Harcourt, Rivers states, Nigeria.

Michalczyk. Department of Plant Physiology, Genetics and Biotechnology. University of Warmia and Mazury in Olsztyn, Poland.

Received Date: November 03, 2020; Published Date: July 28, 2021

Abstract

Uganda agriculture is endowed with fertile soils and agro-ecology climate for agricultural potentials development. The agriculture sector remains the backbone of Uganda’s economy and it is a source of livelihood for most of the population. It contributes to 72% of the total labour force, 25.3% of the country’s gross domestic product (GDP), and it accounts for 54% of total export earnings and 66% of the country’s working population is engaged in agriculture where 83% are women. Organic 3.0 agriculture practice will enable development of sustainable farming systems and markets based on organic principles driven by innovation, best practice, integrity, collaboration, holistic systems, and value driven pricing to increase overall productivity and quality for sustainable development. The farming systems are: Intensive banana-coffee lakeshore system, medium altitude intensive banana-coffee system, western banana-coffee-cattle system, banana-millet cotton system, annual cropping and cattle Teso system, annual cropping and cattle West Nile system, annual cropping and cattle Northern system, pastoral and some annual crops system, and montane systems. Savannah Shea tree has great potentials for shea butter industry and the shea cake waste converted to biofertilizer and biopesticides production for re-generative agriculture development in Uganda.

Keywords: Biofertilizer; Biopesticide; Cattle; Cash Crops; Gap and Need Analysis; Organic 3.0 agriculture; Shea value chain development; Uganda Agriculture

Abbreviations and Acronyms:

ASSP - Agriculture Sector Strategic Plan.

CAADP - Comprehensive Africa Agriculture Development Program.

DSIP - Development Strategy and Investment Plan.

EAC - East African Community.

GDP - Gross Domestic Product.

SGD - Sustainable Development.

MAAIF-Ministry of Agriculture, Animal

Industry and Fisheries.

NDP - National Development Plan.

NEPAD - New Partnership for Africa’s Development.

Organic 3.0 - Enable a widespread uptake of truly sustainable farming systems and markets based on organic principles and imbued with a culture of innovation, of progressive improvement towards best practice, of transparent integrity, of inclusive collaboration, of holistic systems, and of true value pricing.

UGX - Ugandan shilling.

UNAP - Uganda Nutrition Action Plan.

UBOS - Uganda Bureau of Statistics.

Introduction

The need for the agriculture sector, through its lead ministry, to actively participate in actions aimed at reducing malnutrition is premised on global, regional and national frameworks, notable among them, the Sustainable Development Goals (SDG), the 2001 New Partnership for Africa’s Development (NEPAD), the 2002 Comprehensive Africa Agriculture Development Programme (CAADP), the 2015/16 - 2020 Agriculture Sector Strategy Plan (ASSP), and the 2011–2016 Uganda Nutrition Action Plan (UNAP). The agriculture sector remains the backbone of Uganda’s economy and it is a source of livelihood for most of the population. It contributes to 72% of the total labour force and 25.3% of the country’s gross domestic product (GDP), and it accounts for 54% of total export earnings1. In addition, about 66% of the country’s working population is engaged in agriculture3. The proportion of women engaged in agriculture is 83%2. Women are thus significant contributors to household food security and nutrition, and they are also particularly adversely affected by food insecurity and malnutrition. Agricultural growth leads to economic growth and poverty reduction, manifested as higher per capita GDP4. Higher per capita GDP is associated with increased expenditure on food and nutrition5, which may help reduce malnutrition6. The agricultural trading is focused on organic 3.0 enable a widespread uptake of truly sustainable farming systems and markets based on organic principles and imbued with a culture of innovation, of progressive improvement towards best practice, of transparent integrity, of inclusive collaboration, of holistic systems, and of true value pricing. A culture of innovation, to attract greater farmer conversion, adoption of best practices and to increase overall productivity and quality for sustainable development.

Gap and need analysis

A training needs assessment identifies individuals’ skill based on Uganda agricultural resources potentials. The difference between the current and required competencies can help determine training needs. Rather, than assume that all employees /agriculture sector need training or even the same training, management can make informed decisions about the best ways to address competency gaps among individuals in a sector, specific job categories or groups / teams. The objective of the paper is the Uganda agriculture human capital development position paper relative to its agriculture potentials using the ‘gap and need analysis.’ The training need

FOOT NOTES

1National Planning Authority (2015) Second National Development Plan 2015/16–2019/20. Kampala: National Planning Authority of Uganda.

2Uganda Bureau of Statistics (2012) 2012 Statistical Abstract. Kampala: Uganda Bureau of Statistics.

3Ibid.

4Grehal, Bahjan et al., (2012) The Contribution of Agricultural Growth to Poverty Reduction: ACIAR Impact Assessment Series Report No. 76. Canberra: Australian Centre for International Agricultural Research.

5Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO), World Food Programme (WFP) and the International Fund for Agricultural Development (IFAD) (2012) The State of Food Insecurity in the World 2012. Economic growth is necessary but not sufficient to accelerate reduction of hunger and malnutrition. Rome: FAO.

6Ministry of Agriculture, Animal Industry and Fisheries (MAAIF) (2013) National Agriculture Policy. Kampala: MAAIF.

assessments can be conducted by agriculture risk performance review using the agriculture development plans and SDG. Performing a gap analysis involves assessing the current state of agriculture development performance or skills and comparing this to the desired level of SDG. The difference between the existing state and the desired state is the gap analysis. The results of a agriculture training needs analysis (TNA) is a plan to encapsulated targeted, effective activities that can improves live hoods and the focus are:

• Work out the areas of greatest need.

• Optimize agriculture potentials.

• Training on ecological agriculture.

Uganda vision 2040

The Ugandan National Planning Authority’s Vision 2040 recognizes the need to promote good health and nutrition, especially for young children and women of reproductive age. The projects outcomes for those two groups can reduce the number of maternal and child deaths by over 6,000 and 16,000 per year, respectively, as well as increase national economic productivity, both physical and intellectual, by an estimated UGX 130 billion per year.

The millennium development goals and sustainable development goals

Goal 1 of the United Nations Millennium Development Goal (1990 -2015) was to reduce extreme hunger and poverty. With reference to hunger, the target was to halve the proportion of people who suffered from hunger, which would ultimately result in a reduction in underweight among children under 5 years of age, as well as a reduction in the proportion of the population consuming insufficient dietary energy. The need to reduce hunger has been reechoed in the Sustainable Development Goals (SDG).

In particular, Goal 2 aims to end hunger, achieve food security, improve nutrition and promote sustainable agriculture of Africans - get better access to markets, finance and technical support in order to improve their incomes and get out of poverty. Agricultural development on the continent is driven through New Partnership for Africa’s Development (NEPAD) and Comprehensive Africa Agriculture Development Programme (CAADP) the objective of which is to raise agricultural productivity in Africa to at least 6% annually, to contribute to poverty alleviation and the elimination of hunger and food and nutrition insecurity.

The National Agriculture Policy Food and nutrition security are emphasized in the National Agriculture Policy9, whose strategic policy actions are:

• Promoting agricultural enterprises that enable households to earn daily, periodic and long-term incomes to support food purchases.

• Promoting and facilitating the construction of appropriate agro-processing and storage infrastructure at appropriate levels to improve post-harvest management, add value and enhance marketing.

• Developing and improving food handling, marketing and distribution systems, and linkages to domestic, regional and international markets.

• Supporting the establishment of a national strategic food reserve system.

• Supporting the development of a well-coordinated system for collecting, collating and disseminating information on agricultural production, food and nutrition security across households, communities and agricultural zones.

• Encouraging and supporting local governments to enact and enforce bylaws and ordinances that promote household food security through appropriate food production and storage practices.

• Promoting the production of nutritious foods, including indigenous foods, to meet household needs and for sale.

• Promoting the consumption of diverse nutritious foods, including indigenous foods, at the household and community levels.

• Promoting appropriate technologies and practices to minimize post-harvest losses along the entire commodity value chain.

Gap Analysis

Regular incomes flows

The explicit focus of the agriculture policy on increasing household incomes and trade suggests that income growth is already an implied core responsibility of all extension agents in enterprise promotion of agriculture. Thus, as we integrate human capacity development, nutrition sensitivity into enterprise mix design, income gains should remain a prominent issue [1].

Impoverished households face difficult decisions on how to allocate their spending, and evidence shows that the poor purchase and consume greater amounts of cheap, energy dense foods that are filling, but have lower nutritional quality, as compared to higher income households7. In addition, in agricultural systems, high levels of income may have relatively little impact on nutrition if income

FOOT NOTES

7Food Research and Action Centre (2016) ‘Fighting Hunger and Obesity’. Available at: http://frac.org/initiatives/hunger-and-obesity.

8Kikafunda JK, Agaba E, Bambona A (2014) ‘Malnutrition amidst Plenty: An Assessment of Factors Responsible for Persistent High Levels of Childhood Stunting in Food Secure Western Uganda’. African Journal of Food, Agriculture, Nutrition and Development 14: 5.

9Choudhary, Vikas Engelen, Anton Van, Sebadduka Sam, Valdivia Pablo (2011) Uganda dairy supply chain risk assessment. Washington D C: World Bank. Fish, poultry, rabbits, pigs and goats have higher feed conversion rates, shorter production cycles, and are easy to rear and sell than cattle.

flows are not well planned throughout the year. Research has shown that regular income flows (e.g., weekly or monthly) lead to improved household welfare, including better nutrition outcomes, especially when controlled by women8. Therefore, it is important to promote livestock and crop enterprises that favor women, which will ensure that they control the income. However, regardless of who controls the income, it is always important to ensure that it is invested in household.

Livestock production

One advantage for households with dairy cows is that milk is available throughout the year for household consumption and goat, sheep (small animals) for the market. In addition, milk sales can provide a continuous source of income. It is estimated that about 70% of milk in Uganda is sold commercially, compared to about 30% consumed on the farm. About 90% of raw milk sales occur though informal channels in local markets and little of this milk is processed, although a small and growing cottage industry of household processors is producing yoghurt, cheese and other products [2]. A small number of commercial processors produce pasteurized milk, Ultra High Temperature milk, cheeses, milk powder, yoghurt, etc. Cross-bred cows can be managed under zerograzing for small landholdings, and with relatively reduced animal healthcare input costs. However, exotic pure - or cross-bred cows require a relatively large investment as well as proper animal husbandry practices, access to veterinary and other extension services, and feed. Resource-poor farmers may not be able to afford exotic breeds of cattle and thus, may need to select other affordable livestock, such as poultry, rabbits, goats and/or pigs.

Crop enterprises with regular cash flows

Most crop enterprises are seasonal. Very few allow regular income flows, unless their planting is staggered and/or households have access to irrigation technologies for off-season production.

A few examples of crop enterprises with regular income flows include horticulture, banana production, mushroom growing, and irrigated vegetable production. Alternatively, a mix of livestock and crops enterprises often brings more income than one or the other alone, because there are close links between crop and livestock production that provide flexibility in matters such as choice of tilling and manure application times, 9 as well as crop residues for animal feed10. Most exotic breeds of livestock are reared in commercial integrated systems. The most significant risk is disease, particularly New Castle disease in poultry, which requires that smallholders have access to veterinary services and/or medicines, or they risk losing most or all of their flock11.

Promotion of access to off-farm income: The role of food processing and preservation

FOOT NOTES

10Most exotic breeds of livestock are reared in commercial integrated systems. The most significant risk is disease, particularly New Castle disease in poultry, which requires that smallholders have access to veterinary services and/or medicines, or they risk losing most or all of their flock.

11Njuki, Jeminah, Sanginga, Pascal (2014) Gender and Livestock: Key Issues, Challenges and Opportunities. Brief. Nairobi: International Livestock Research Institute.

The promotion of off-farm income-generating activities is another way to promote regular income flows for farming households, as insurance against food price hikes, hiccups in weather patterns and poor yields, all of which can lead to food and nutrition insecurity. Food processing, especially if rurally based, is very important for ensuring off-farm income. While crop enterprises are seasonal, food processing and preservation can allow almost continuous marketing of products, provide associated income flows throughout the year, and increase total household earnings. Other interventions in the community that allow for regular, off-farm income also have potential positive food security effects [3]. These include training farmers in skills such as carpentry and bricklaying, among others. In communities where agriculture is a dominant activity, these skills can be useful in servicing the agriculture system; for instance, to repair agriculture machinery and equipment, or build water harvesting infrastructure (Figure 1).

Household - or cottage-level food processing increases participation in the food value chain and can have a mobilizing and empowering effect on the community. Farmers’ groups, for example, can be organized to process and market products such as fruit juices, jam, dried fruit chips, and vegetable and animal products. These practices also help to ensure that processed foods meet standards for commercial sale, in the event that the cottagelevel industries continue to grow. Extension workers need to train and sensitize farmers and cottage level food processors about good manufacturing practices and good hygiene practices during processing. Promoting food quality and safety along the agriculture value is essential for:

• Maintaining the wholesomeness of food products, both physically and nutritionally Eliminating spoilage by microorganisms and prolonging the shelf life of the food products

• Eliminating pathogenic micro-organisms such as salmonella, E.coli, and aflatoxin-producing mould, which would otherwise contaminate food products.

• Eliminating spoilage by micro-organisms and prolonging the shelf life of the food products.

Protection of the environment and ensuring household resilience

Climate change is already affecting food security in Uganda through reduced production of major food crops as a result of increased occurrences of droughts, floods and soil erosion through landslides (NEMA,2008). Prolonged dry spells and high temperatures reduce productivity, particularly for rain-fed production, and can lead to new crop pests and animal diseases. Floods pose immediate danger to people, livelihoods property and can cause crop damage (Figure 1).

Households with limited savings and other assets are especially vulnerable to external shocks, such as climate change and fluctuations in crop prices, as well as internal shocks, such as a death in the family, prolonged sickness, or loss of remittance support. For the poorest households, even small shocks can push them over the edge, requiring them to sell productive assets, forego health care, or reduce food consumption (see Appendix 1) below (Biofertilizer manufacturing). This into extension activities will enhance smallholder capacity to deal with sudden changes in the agricultural environment on which they depend. Men and women use natural resources in different ways and employ different allocation and conservation measures12. Understanding the different roles and responsibilities of men and women in environmental management is critical to understanding how these will affect productivity, sustainability, and inevitably, food security and nutrition (Figure 2). However, it should be appreciated that women are the ones mostly involved in subsistence farming activities, where they inevitably interact with the environment, which they depend on. Therefore, extension workers need to understand gender-specific knowledge and practices in environmental management. Some of the required actions are only possible at the (national) policy level, while others can be undertaken at the extension (community) level [4,5].

Organic 3.0

The organic timeline can be measured in approximately 100 years: from the early days of imagining organic by those who saw the connections between how we live, eat, and farm, our health and the health of the planet (what we call ‘Organic 1.0’) ; to the forming of the movement and the codification of standards and enforced rules that have established organic in 82 countries with a market value of over $72 billion per year economy today (what is termed ‘Organic 2.0’). ‘Organic 3.0’ is agriculture sustainable innovation. Agriculture is one of the leading factors in global issues of hunger, inequity, energy consumption, and pollution, and climate change, loss of biodiversity and depletion of natural resources. And yet, the positive, multi-faceted environmental, social and economic benefits of a truly sustainable agriculture can contribute solutions to most of our world’s major problems. If mainstream agriculture were to adopt more organic practices and principles, the need for Organic 2.0 would cease to exist. Until now, though, organic has not been included - or inclusive - enough to contribute these solutions on a global scale.

The Organic 3.0 concept seeks to change this, by positioning organic as a modern, innovative system which puts the results and impacts of farming in the foreground*.

The overall goal of Organic 3.0 is to enable a widespread uptake of truly sustainable farming systems and markets based on organic principles and imbued with a culture of innovation, of progressive improvement towards best practice, of transparent integrity, of inclusive collaboration, of holistic systems, and of true value pricing. Six (6) components of Organic 3.0 includes:

• A culture of innovation, to attract greater farmer conversion, adoption of best practices and to increase overall productivity and quality;

• Continuous improvement toward best practices, at a localized and regionalized level;

• Diverse ways to ensure transparent integrity, to broaden the uptake of organic agriculture beyond third-party assurance and certification;

• Inclusiveness of wider sustainability interests, through alliances with the many movements and organizations that have complementary and fair approaches to truly sustainable food and farming;

• Holistic empowerment from the farm to the final product, to acknowledge the interdependence and real partnerships along value chains and also at the territorial level; and

• True value and fair pricing, to internalize costs, encourage transparency for consumers and policymakers and to empower farmers as full partners.

Uganda Agriculture

The agricultural sector is still the mainstay for a large part of the Ugandan population. But while the contribution to GDP (22.5% in 2013/14), exports (54% in 2014) and employment (70%) is still high, the growth rate of the sector is way below average GDP growth. The low growth rate can be attributed to weather hazards, economic downturns, limited availability of improved inputs, diversion of investment into the industrial sector, and/or insurgencies in neighboring countries. Uganda is gifted with fertile soils and a favourable climate having one of the best environments for agricultural production in Africa. The agricultural sector in

FOOT NOTES

12International Fund for Agricultural Development (IFAD), Rural Poverty Report 2001: The Challenge of Ending Rural Poverty. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

*https://www.academia.edu/42632817/Gateway_Organic_

Fertilizer_Biofertilizer_Gateway_Biofertilizer_Organic_3_0

https://www.academia.edu/41445902/ARATI_Biopesticide_Microbial_Granular_and_Liquid

https://www.academia.edu/41445611/ARATI_Yaranta_Bioherbicide_

Gateway Organic Fertilizer | Biofertilizer Gateway Biofertilizer Organic 3.0 and Appendix 1 below.

Uganda includes food crops, cash crops, floriculture, livestock, forestry and fishery, and employs more than 70% of the working population [6].

Despite the importance of agriculture to the economy, the growth of the agricultural sector (at 1.5% in FY 2013/14) is still much below the National Development Program (NDP) annual growth target of 5.6% and the 5.9 % growth rate that is required for effective poverty reduction. It is also below the 6% annual growth target of the African Union’s Comprehensive Africa Agriculture Development Program (CAADP). Agricultural products make up nearly all of Uganda’s foreign exchange earnings and continue to contribute more than half of Uganda’s formal export earnings, although the percentage has gone down from 61% in 2005 to 54% in 2014. However, exports of non-traditional products, such as vegetables, maize, cocoa beans, soybeans and oilseeds are growing, while traditional exports such as coffee, cotton, tea, and tobacco remain strong.

Due to the significant increase in the coffee earnings in 2013 the overall formal export earnings increased from 25.1% in 2012 to 27.5% - in 2013. Overall, coffee remained the main foreign exchange earner for the last five years; followed closely by tobacco, tea and cotton (UBOS,2014) [7,8].

The share of the Non-Traditional Exports (NTEs) to total formal export earnings slightly dropped from 74.9% in 2012 to 72.5% in 2013. However, total non-traditional earnings steadily increased over the same period due mainly to increased contributions from fish and fish products and animal, vegetable fats and oils. Despite its diversity of agricultural products, Uganda imports many agricultural products including vegetable fats and oils, sugars and sugar preparation, honey, organic chemicals, Oilseeds, oleaginous fruits and animal feeds.

Land use

Uganda has an area of 241,550.7 square kilometers of which 18.2% is open water and swamps, and 81.8% is land. The altitude above sea level ranges from 620 meters (Albert Nile) to 5,111 meters (Mt. Rwenzori peak). A total of 42% of the available land is arable land although only 21% is currently utilized, mostly in the southern parts of the country. Land is fairly evenly distributed throughout the country with the average land holding being about 1.6 to 2.8 hectares in the south and 3.2 hectares in the north (where the climate tends to be drier and larger landholdings are required for sustainable management of farms). The vegetation is mainly composed of shrubs, savannah, grassland, woodland, bush land and tropical high forest [9].

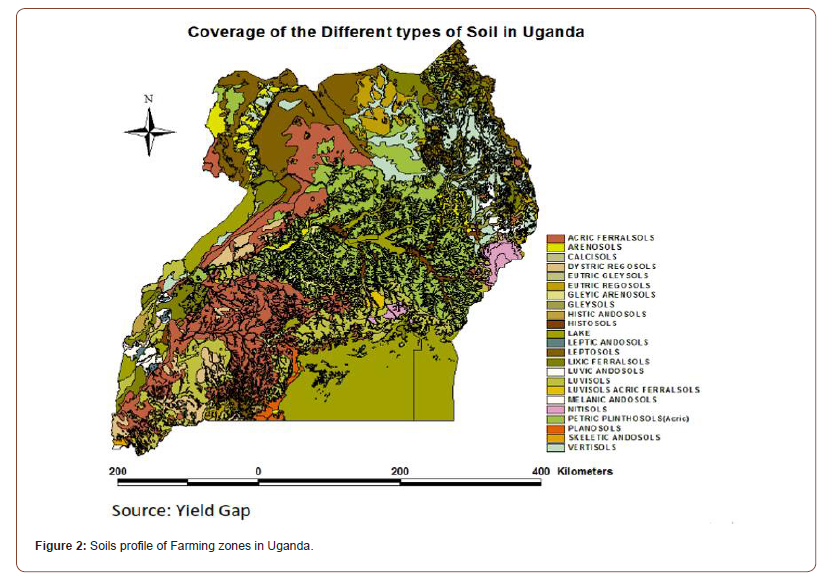

Soils

According to Parsons (1970), the soils of Uganda have been classified according to levels of productivity. Of the land area 8% have high productivity soils, 14% medium productivity soils, 43% fair productivity soils, 30% low productivity soils, and 5% negligible productivity soils. The main soil types in Uganda are 18 divided into 7 groups based on their occurrence and agricultural productivity:

• The Uganda surfaces cover most areas south of Lake Yoga. This group embraces five types of deep, sandy clay loams with medium to high productivity.

• The Tanganyika surfaces cover most areas north of Lake Kyoga, West Nile and some parts of the South Western tip of Uganda, embracing five types of sandy clay loam with low to medium productivity.

• The Karamoja surfaces cover the North Eastern part of the country and embrace two soil types of sandy clay loams and black clays with very low productivity.

• Rift valley soils in the Western and Northern parts of the country, bordering on the Western Rift Valley, embracing two types of mainly sandy clay loams with alluvial parent rock of medium to high productivity, Figure 1.

• Volcanic soils are dominant in Mt. Elgon, Northern Karamoja, and the extreme South Western tip of Uganda (Kabale and Kisoro) with medium to high productivity except in N. Karamoja where their productivity is low.

• Alluvial soils are found outside the Rift Valley, mainly in Central Northern Uganda (Lango and Acholi) as well as West of Lake Victoria. The productivity of these sandy soils is very low

• The last group of soil types is in Northern Uganda and their productivity is low.

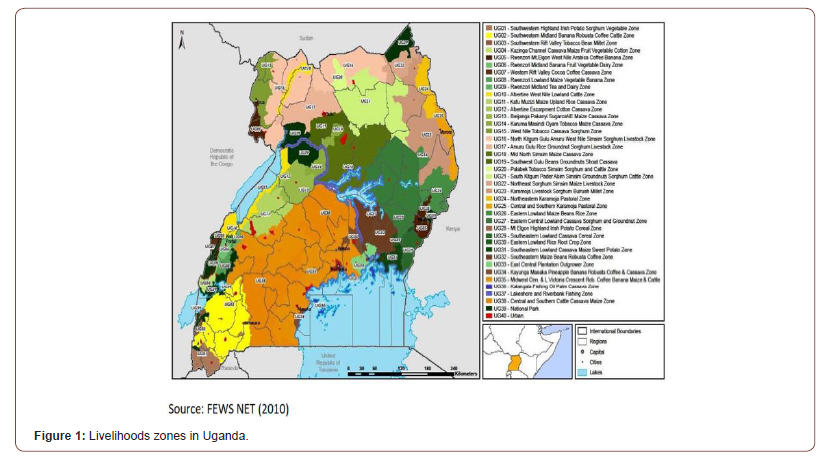

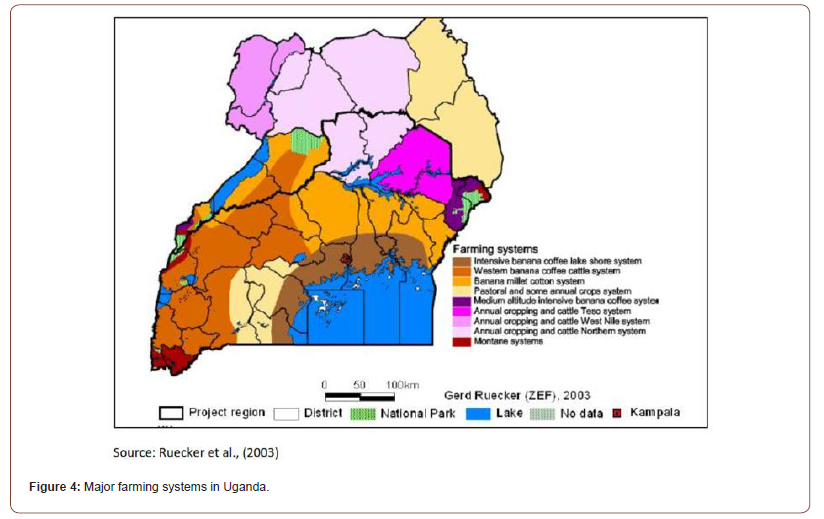

Farming systems

The farming systems vary across Uganda based on climatic and soil conditions, cultural practices, etc. The nine major farming systems are: 1) Intensive banana-coffee lakeshore system, 2) Medium altitude intensive banana-coffee system, 3) Western banana-coffee-cattle system, 4) Banana-millet cotton system, 5) Annual cropping and cattle Teso system, 6) Annual cropping and cattle West Nile system, 7) Annual cropping and cattle Northern system, 8) Pastoral and some annual crops system, and 9) Montane systems. Within these major farming zones, a multitude of agricultural practices are applied. Even within one major farming system, farmers are affected differently by agricultural risk as the combination of crops grown varies. Therefore, a more detailed breakdown of sources of income can be found in the livelihood zoning map hereafter (Figure 1).

Livelihood zoning is the first step taken in the process towards the creation of livelihood profiles or baselines for a specific geographic area [10-13]. The objective is to group together people who share similar options for producing food and cash‐crops and livestock, securing cash income and using the market, how they are affected by hazards such as rain failure or crop disease, which is related to geographical location. For example, pastoralists and cultivators have different measures of what constitutes poor rains and/or drought, and they have different responses to these threats. Comparative livelihoods information provides a solid base for monitoring food security amongst a population, thereby helping governments and international agencies to prevent humanitarian disasters. In most developing countries, such as Uganda, livelihoods are based significantly on the production of food crops, cash crops, and livestock, which play an important role even outside pastoral and agro‐pastoral areas making agro‐ecological mapping play a dominate role in livelihood zoning. Other elements also play a role in livelihood zoning such as accessibility to roads and markets, or proximity to large cities, irrigated plantations, local culture and government policy decisions.

Focus on smallholders. The current production structure of agriculture in Uganda is dominated by small-scale farmers comprising of an estimated 2.5 million households (90% of the farming community), the majority of who own less than 2 acres of land each. Despite good agro-climatic conditions with two rainy seasons in most parts of the country, yields of smallholder farmers remain low [14]. Limited access to quality inputs, low adoption of modern technology, and lack of storage and market infrastructure are constraints to the sector.

Commodities

Cash crops

Uganda the major cash crops are coffee, tea, cotton, tobacco, cocoa, sugar cane and exported flowers, fruits and vegetables (Figure 4). There are two types of coffee grown in Uganda.

Robusta coffee and Arabica coffee with Robusta being produced more than Arabica. The majority of cash crops, including tobacco, tea, cocoa and coffee. Post-harvest management of cash crops (see Appendix 2).

Food crops

Uganda grows about sixteen major food crops namely; Cereals (maize, millet, sorghum, rice); Root crops (cassava, sweet potatoes, Irish potatoes); Pulses (beans, cowpeas, field peas, pigeon peas); and Oil crops (groundnuts, soya beans, sesame), bananas, and plantains. Additionally, wheat is increasingly become a major food crop in Uganda and should be included in the major food crops. The Eastern region leads in the production of cereals and root crops followed by the western and northern region. The northern region leads in the producer of oil crops, followed by the eastern region [15]. The western region led in the production of all types of banana and plantains, followed by the central region. The national estimates of food crops in Uganda show that the majority of food crops such as bananas, cassava, sorghum, millet, beans, ground nuts, soya beans, sesame, sweet and Irish potatoes registered increments in production (see Appendix 2).

Livestock’s

Diseases are a major factor for the livestock sector. The economic impact of diseases on farming households is diverse: farmers incur cost for disease control, treatment, and vaccination. Direct losses are associated with animal mortality, reduced milk production, and use of animal for traction. A recent study in the three agro-pastoral systems of Uganda [16] revealed that farmer’s annual average economic cost due to diseases per head of cattle was: USD$ 14.27 for farmers in semi-humid agro-pastoral land; USD$ 5.31 in humid mixed crop-livestock systems; and USD$ 7.62 in semiarid pastoral systems (Figure 3).

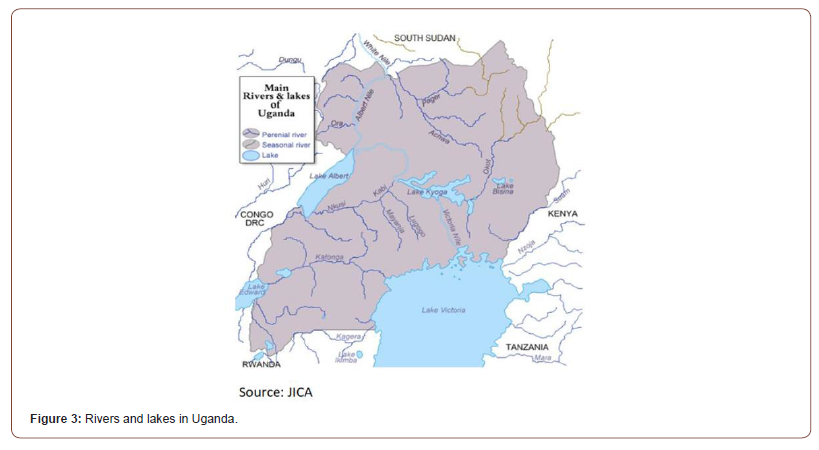

Fisheries

The Fisheries sector is comprised of both capture and culture (aquaculture) fisheries with the former contributing most of total production. The capture fishery is basically artisanal while aquaculture is increasingly becoming commercialized because of the increased demand for fish and noticeably reduction in catches from capture fisheries .The water bodies of Uganda comprises of five major lakes (Victoria, Albert, Kyoga, Edward and George and about 160 minor lakes, rivers and wetlands), and have an estimated production potential of over 800,000 tons of fish although the current catch was estimated at 419,000 MT in 2014 [17].

Lake Victoria continues to be the most important water body in Uganda both in size and contribution to the total fish catch. It is important to note that over 90% of the fish catch is harvested from Lakes: Victoria, Albert and Kyoga (Figure 3).

Forestry

Forests in Uganda are defined to include all alpine, tropical high-and medium-altitude forests, woodlands, wetland and riparian forests, plantations and trees, whether on public or private land (Ministry of Water, Lands and Environment, 2001). In 1990s, forest cover was estimated at 4.9 million hectares (24% of the land area), of which 81% (3,974,000 ha) was woodland, 19% (924,000) was tropical high forest and <1% (35,000 ha) was forest plantations (National Environment Management Authority NEMA 2002). However, growth in human population and corresponding increase in demand for forest products for domestic and industrial use, expansion of agricultural land, illegal settlements and weak forest management capacity have adversely affected the status of natural forests in Uganda, reducing it to 17% (3,556,000 ha) of total land area of the country [18-21].

Structure of the agricultural sector

The majority (96%) of the agricultural households still rely on the hand hoe as the source of farm power and still depend on local seed (92%) as the main planting material; only 31% use improved seeds and/ or tractors (0.8%). Food shortages were experienced by 51% of the agricultural households with crop loss as the main reason for the food shortage, mainly attributed to drought and to pests and diseases. Irrigation is rarely practiced (0.9 %) and flooding and swamp drainage are most common in the Eastern region, which accounts for more than half (52%) of the drained area in Uganda (Figure 2-4).

The most important source of agricultural information for farmers was from radio and farmer to farmer communication. Radio was the main source of information on weather (85 %), farm machinery (44%) and credit (50%), whereas farmer to farmer communication was the major source of information on crop varieties (43%), new farming methods (40%), diseases and pests (45%) and agricultural market information (51%). Bicycles are the most common means of transport and are owned by 51% of the agricultural households. Low numbers (9.1%) of the agricultural households had accessed credit and only 51% had storage facilities. The most important source of agricultural information for farmers was from radio and farmer to farmer communication. Radio was the main source of information on weather (85%), farm machinery (44%) and credit (50%), whereas farmer to farmer communication was the major source of information on crop varieties (43%), new farming methods (40%), diseases and pests (45%) and agricultural market information (51 %). Bicycles are the most common means of transport and are owned by 51% of the agricultural households. Low numbers (9.1%) of the agricultural households had accessed credit and only 51% had storage facilities. The Ugandan government has initiated infrastructure development programs geared towards improving marketing efficiency; however, a lot still needs to be done to improve marketing of agricultural commodities, lack of proper infrastructure which is an essential ingredient for efficient marketing of finished goods and services. Improving agricultural marketing requires improved marketing infrastructures such as roads, railways, water transport, and telecommunications [22-25].

One of the greatest hindrances to efficient agricultural marketing in Uganda is the high transport cost associated with moving products from remote rural areas to urban markets. High transport cost may be due to the high cost of fuel, poor roads, lack of competition or a combination of all these and other factors. High transport costs translate into high retail prices for urban consumers. Road transport is the major means of transporting agricultural products in Uganda (Figure 5) (Plate 1) (Table 1).

Table 1: Threats to local conservation of mature Shea trees and seedlings (Buyinza and Lamoris,2015).

FOOT NOTES

*Shea Technology and Shea Biofertilizer Application: Cassava cultivation

https://www.academia.edu/41484486/SHEA_PADDIS_Three_Dimension_Architectural_Design

https://www.academia.edu/41335213/Biofertilizer_Impacts_on_Cassava_Manihot_Esculenta_Crantz_Cultivation_Improved_Soil_Health_and_ Quality_Igbariam_Nigeria

The railway network is underdeveloped and poorly maintained. Transport services across rivers and lakes are limited. Future expansion and increase in productivity in agriculture depends to a great extent on the sector’s ability to produce cheaply and be able to compete in regional and international markets. There is a general belief that Uganda can be the hub of the Great Lakes region in term of food supply. However, Uganda is a high cost producer and it is not clear how many of the country’s main agricultural products can effectively compete within the regional markets (Figure 2).

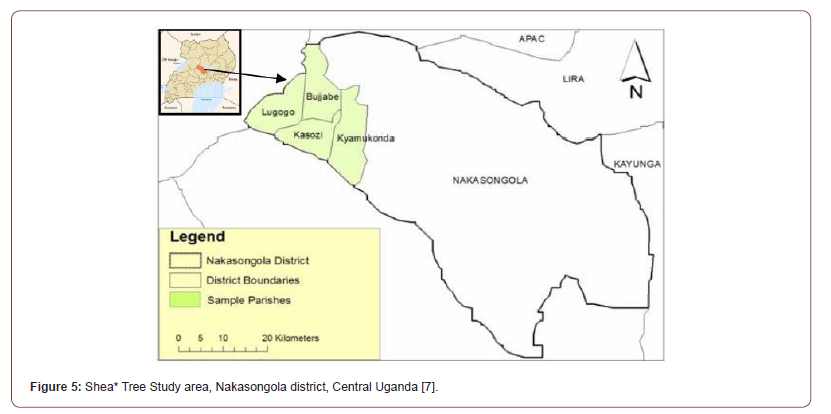

Shea Butter Production

Location | Nakasongola district, Central Uganda

The shea butter tree (Vitellaria paradoxa C.F. Gaertn. subsp. nilotica (Kotschy)) is an indigenous woody plant of savannah parklands13 and plays an important role in improving household incomes for rural people14 Local communities rely on it mainly for fruits, nuts, oil or fats for domestic consumption and cash sales15-17 The tree remains virtually a wild species with very little agronomic research on shortening its juvenile period before fruiting. Unsustainable exploitation of shea parklands has placed additional pressure on the natural regeneration of the tree18 Although Uganda signed the Convention to Combat Desertification (CCD) in 1994 and ratified it in 1997, there is still massive destruction of indigenous tree species especially for fuel in form of charcoal. Masters and Puga19 report that in some areas of Uganda, the Vitellaria tree is cut for charcoal making in spite of its economic importance as a source of cooking oil [26].

According to Maxted et al,. (1997)20 on-farm conservation is the sustainable management of genetic diversity of locally developed traditional crop varieties, with associated wild and weedy species of all forms, by farmers within traditional agricultural, horticultural or agri-silvicultural cultivation systems.

It is an approach to in-situ conservation of genetic resources, focusing on conserving cultivated plant species in farmers’ fields21.

FOOT NOTES

*https://www.academia.edu/41445902/ARATI_Biopesticide_Microbial_Granular_and_Liquid

www.globalshea.com/.../aratishea_shea_cake_waste_conversion_to_biopesticide_779. http://aratibiotech.com/pc3r-technology/13World Bank, Integrating gender into development projects: Gender and natural resource management (http://info.worldbank.org/ etools/docs/library

14Hall JB, Aebischer DP, Tomlison HF, Cosei-Amaning E, Hindle JR (1996) Vitellaria paradoxa, a monograph, School of Agriculture and Food Sciences, Bangor 8: 105.

15Okullo JBL, Hall JB, Obua J (2004) Leafing, flowering and fruiting of Vitellaria paradoxa subsp. nilotica in savannah parklands in Uganda, kluwer Academic Publishers, Netherlands, 14.

16Gwali S, Okullo JBL, Eilu G, Nakabonge G, Nyeko P, Vuzi P (2011) Folk classification of Shea butter tree (Vitellaria paradoxa subsp. nilotica) ethno-varieties in Uganda. Ethnobot. Res Appl 9: 243-256.

17Byakagaba P, Eilu G, Okullo JBL, Tumwebaze SB., Mwavu EN, (2011) Population structure and regeneration status of Vitellaria paradoxa (C.F.Gaertn.) under different land management regimes in Uganda, Agric J 6(1): 14-22.

18Okiror P, Agea JG, Okia CA, Okullo JBL (2012) On-Farm Management of Vitellaria paradoxa C. F. Gaertn. In: Amuria District, Eastern Uganda, Int J For Res. doi:10.1155/2012/768946

19Obua J (2002) Conservation of Shea parklands through Local Resource Management, International Workshop on Processing and Marketing of Shea products in Africa, proceedings, CFC Technical paper No. 21.

20Masters ET, Puga A (1994) The Shea Project for Local Conservation and Development, Otuke County, Lira District, Northern Uganda.

21Maxted NJG, Hawkes BV, Ford-Lloyed, Williams JT (1997) A Practical Model for In situ Genetic Conservation. The Insitu Approach, London.

It is a form of management from which tangible benefits can be accrued. Though not normally planted by farmers given its long juvenile period, regeneration of Vitellaria paradox species can be facilitated by human management such as covering germinated seeds with mulch and through protection of the shea seedling when clearing land for cultivation22.

However, due to the high costs of planting trees, conservation interest should shift to protection and stimulation of natural tree regeneration especially where mother trees are available23. The expose document the major threats to conservation of the shea butter tree and the socio demographic factors influencing people’s willingness to plant the tree. Extensive degradation of parklands occurs along livestock routes, watering points, hill tops and areas where charcoal burning is mainly practiced24,25. The combination of human population growth, traditional nomadic sentiments of overstocking and invasion by agricultural and ranching settlers has resulted into over utilization and irreversible damage of Nakasongola parklands. The area under grassland in Nakasongola has declined from 78,100 ha to just 40,182 ha due to overstocking of livestock, regular bush fires and burning of charcoal26. Charcoal burning is the biggest threat to shea conservation in Nakasongola District (Table 1).

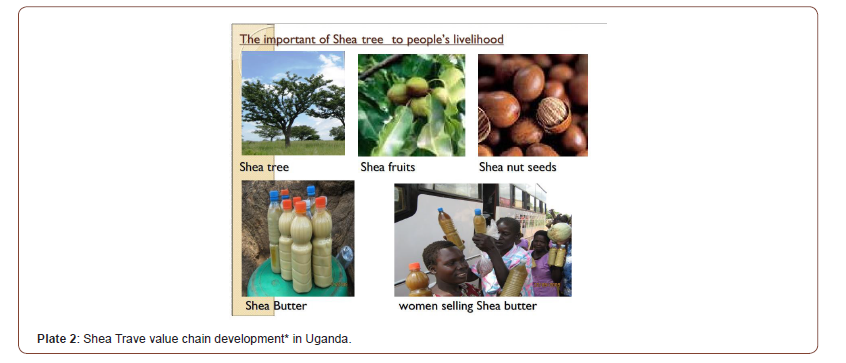

Solution - proposed

Shea nut tree* is a slow-growing savannah hardwood fruits trees indigenous to Northern Uganda and is controlled by women. It produces fruits which is widely eaten. Inside the nutritious fruit is a large hard seed which yields Shea-butter, locally known as Moo Yaa in Acholi. It is used as an essential food-oil, cosmetic, sacred substance and to raise income. Historically, these trees have been protected because of value. However, increasing population pressure and need for fuel wood has led to greater destruction of the Shea trees. Shea trees produce a very high quality charcoal that produces much heat energy. Shea tree is of great value to the local people in Uganda. In 1992, Cooperation Office for Voluntary Organisation (COVOL) started a Shea conservation project in Lira. The project received funding in 1995 from USAID and further expanded to Katakwir, Pader, Gulu, Amuria, Amuru, Abim and Kitgum. The project became short off when insecurity in the region deteriorated in 2006 .

The situation is also expected to worsen further in the course of former internally displaced persons returning to their homes. Beekeeping had been identified by KITWOBEE as a sustainable approach that can be used to inspire the local communities to conserve Shea nut trees in Uganda, Plate 2.

Constrain to conservation of Shea tree: Poor implementation of policy on conservation of national resources. Inadequate knowledge on value of Shea trees to honey production and quality has created ignorance on the protection of Shea trees in Uganda. These includes:

• Poverty and Population increase.

• Local traditional practices of bush burning.

• Limited resources for conserving Shea trees (Plate 1). Way forward:

• Integrating Shea tree conservation and development with beekeeping.

• Paying premium prices for honey produced from Shea nectar.

• Rewarding individual farmers who had managed to protect Shea trees on their farm.

• Implementing the COVOL Project.

• Educating the local population on the value of Shea tree (Plate 2).

• Planting fast maturing agro forestry trees.

• Research and development in Shea technology, see Appendix 3.

FOOT NOTES

*://www.academia.edu/41484398/Shea_Plant_Protection_Science_Specialist

22Jarvis DI, Ribeiro S, Silva ML Ventura D, Ibeiro SA (2000) Training Guide for In Situ Conservation On-farm, IPGRI, Kampala.

23Masters ET (2002) The Shea resource: Overview of research and development across Africa. In: international workshop on processing and marketing of Shea products in Africa-proceedings, Dakar, Senegal, 13-19.

24Boffa JM (1999) Agroforestry Parklands in Sub-Saharan Africa. Forest Conservation Guide no.34. Rome, Food and Agriculture Organisation, 230.

25Green WH (1995) LIMDEP Users’ Manual, Version 7.0, Econometric Software, Inc. Plainview, New York.

26Okullo JBL, Waithum G (2007) Diversity and conservation of on-farm woody plants by field types in Paromo Subcounty, Nebbi District, north-western Uganda, Afr J of Ecology 45(3): 59–66.

27NEMA (2002) (National Environmental Management Authority). State of Environment Report for Uganda, portal Avenue, Kampala, 290.

Recommendation

Beekeeping provides a good opportunity for environmental conservation through local pollination and increases crop yields (Plate 2). Conservation of Shea trees can work well by combining it with beekeeping. Empowering local and forest authorities to arrest individuals who fell down Shea trees. Shea tree can be preserve using biopesticides and the shea cakes can be used for biofertilizer* production [27-29].

Identification Of Agricultural Risks

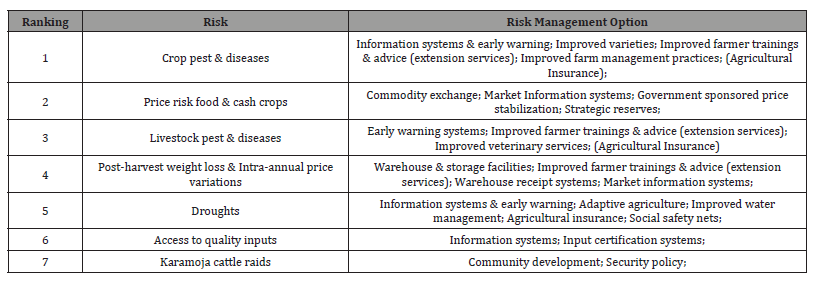

Range of risks for farmers are faced by a plethora of risk The majority of risks are linked to specific stages in the agricultural value chain (e.g. the input risk during the planting and growth stage of the crops). Policy risk, safety risk, and health risk, on the other hand, may occur during any stage of the agricultural production cycle (Table 2). The major risks are:

Table 2: Risk scoring for Uganda.

• Input risk: The problem is a consequence of a poorly developed seed sector where the informal seed system accounts for an estimated 87% of planted seed). The total demand for grain crop seeds is estimated at approximately 110,580 MT, while total sales from the formal seed market account for only 12,000 MT. The supply shortages create incentives for substandard and/or counterfeit seed; studies suggest counterfeiting affects 30-40% of purchased seed.

• Price fluctuations: Inter-annual price variability is a major concern for all major food crops and cash crops. For example, coffee has experienced shocks of up to 49% every 3 years. Matooke /banana are similarly affected while cassava, maize, and potatoes have seen smaller shocks in recent years. On average, losses for farmers due to price risk are estimated at USD$ 262.22 million per annum.

• Crop pests and diseases: Average crops losses in Uganda due to pests, diseases, and weeds are estimated at 10-20% during the pre-harvest period and 20-30% during the post-harvest period. The annual losses for major crops are in the range of USD 113 million to USD 298 million (mainly banana, cassava, coffee, and cotton).

• Post-harvest losses: The weight loss resulting from attacks of pests and animals to major cereals (mostly for maize, but also barley, millet, rice, sorghum, and wheat) cause losses of USD$ 97.17 million p.a. This figure does not yet include opportunity cost for farmers that were forced to sell at low market prices directly after harvesting due to lack of proper storage facilities.

• Livestock pests and diseases: The economic impact of diseases on farming households are diverse: farmers incur cost for disease control, treatment, and vaccination. Direct losses are associated with animal mortality, reduced milk production, and use of animal for traction. The total economic cost for diseases in cattle alone is estimated at USD$ 76.5 million p.a.

• Droughts: Uganda has been hit severely by droughts in recent years (2002, 2005 to 2008, and 2010/11). The return period of large-scale droughts that affected 25,000 people or more is 5.3 years. The average annualized losses amount to USD$ 44.4 million. But drought has the highest probable loss of all risks in Uganda.

• Low quality inputs: Yields for maize, millet, rice, and sorghum are only 20% to 33% of the potential yield for rainfed agriculture and even less for irrigated agriculture. A major

FOOT NOTES

*Liquid Biofertilizer

https://www.academia.edu/43310069/ARATI_BAJA_Liquid_Biofertilizer_Integrated_soil_fertility_management_ISFM

https://www.academia.edu/42632817/Gateway_Organic_Fertilizer_Biofertilizer_Gateway_Biofertilizer_Organic_3.0.

See Appendix 1- Bisofertilizer Technology.

factor is the lack of good-quality, higher-yielding, more vigorous, drought-resistant, and disease-free seeds and planting material. A pronounced problem is the issue of counterfeit inputs that lead to losses to farmers of USD $10.7 to 22.4 million p.a. Impact. Poorer farmers (smallholders) are affected stronger by risk than commercial agriculture (Figure 6).

Ranking of most severe risks (Figure 6). An evaluation of all risks was carried out based on average frequency and severity, and the impact of the worst-case scenario. The following table provides an overview on the scoring. Beekeeping provides a good opportunity for environmental conservation through local pollination and increases crop yields. Conservation of Shea trees can work well by combining it with beekeeping. Empowering local and forest authorities to arrest individuals who fell down Shea trees. Shea tree can be preserve using biopesticides and the shea cakes can be used for shea biofertilizer production* (Appendix 1) (Tables 2&3) (Plate 2).

FOOT NOTES

*https://www.academia.edu/41484418/Shea_Based_Organic_Fertilizers_Impact_on_Crop_Cultivation

*USAID funded Project,1995 (Katakwir,Pader, Gulu, Amuria, Amuru, Abim and Kitgum).

Anchored by Simon Peter Ochola and Margaret Rose Ogaba (kitwobee Beekeeping).

Risk reduction

The critical to raise awareness of farmers on their individual risk exposure and on the best way to protect their livelihoods (Figure 4). This requires well trained and informed extension officers that can provide practical advice to farmers (Table 3). Integrating risk management into the core extension messages is important to help farmers understand how they can reduce, transfer, or cope with risks. Improving the value chain for inputs and developing lowcost storage options for farmers are two other important areas that require further attention. Livestock deaths in Uganda in the recent past. On the crop side, Cassava Brown Streak Virus African, Cassava Mosaic Virus, Banana Bacterial Wilt (BBW), Maize Streak Virus (MSV), Maize Lethal Necrosis Disease (MLND), and groundnut rosette are severely affecting food crops and threatening food security in Uganda. For cash crops diseases such as Coffee wilt and Coffee rust are still not properly managed. On the livestock side, the endemic Newcastle disease in poultry and the sporadic and cyclic outbreaks of African swine fever in pigs wipe out stocks of poultry and pigs in the country every year. Other diseases such as foot and mouth disease, Bovine East Coast fever, and Black quarter although largely managed by routine vaccination still occur in livestock [30].

Table 3: Risk management tools for Uganda.

Conclusions and Recommendations

Human capacity development

The farming systems vary across Uganda based on climatic and soil conditions, cultural practices, etc. (Figures 1 & 4). The nine major farming systems are: 1) Intensive banana-coffee lakeshore system, 2) medium altitude intensive banana-coffee system, 3) western banana-coffee-cattle system, 4) banana-millet cotton system, 5) annual cropping and cattle Teso system, 6) annual cropping and cattle West Nile system, 7) annual cropping and cattle Northern system, 8) pastoral and some annual crops system, and 9) montane systems. Improved data collection and analysis.

Improving data collection and analysis of risk related information is one important strategy to reduce the key risks (pests and diseases for both crops and livestock, and intra-annual price fluctuations). This assessment report has suffered from the lack of information on risks at farm or district level, including information on production, yields and losses. A key issue for improving information systems and early warning is the dissemination of information to smallholder farmers which is currently often lacking. The agricultural training will focus on ecological agriculture called Organic 3.0..The overall goal of Organic3.0 is to enable a widespread uptake of truly sustainable farming systems and markets based on organic principles and imbued with a culture of innovation, of progressive improvement towards best practice, of transparent integrity, of inclusive collaboration, of holistic systems, and of true value pricing and see Appendix 1 below (manufacturing of biofertilizer) [31].

Food crops

Uganda grows about sixteen major food crops namely; Cereals (maize, millet, sorghum, rice); Root crops (cassava, sweet potatoes, Irish potatoes); Pulses (beans, cowpeas, field peas, pigeon peas); and Oil crops (groundnuts, soya beans, sesame), bananas, and plantains. Additionally, wheat is increasingly become a major food crop in Uganda and should be included in the major food crops. The Eastern region leads in the production of cereals and root crops followed by the western and northern region. The northern region leads in the producer of oil crops, followed by the eastern region. The western region led in the production of all types of banana and plantains, followed by the central region. The national estimates of food crops in Uganda show that the majority of food crops such as bananas, cassava, sorghum, millet, beans, ground nuts, soya beans, sesame, sweet and Irish potatoes registered increments in production.

Acknowledgement

None.

Conflict of Interest

The author declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- AdeOluwa OO (2010) Organic Agriculture and Fair Trade in West Africa. Rome, Italy: FAO.

- Adesemoye AO, Kloepper JW (2009) Plant-microbe’s interactions in enhanced fertilizer-use efficiency. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 85 :1-12.

- Adesemoye AO, Torbert HA, Kloepper JW (2009) Plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria allow reduced application rates of chemical fertilizers. Micro Ecol 58: 921–929.

- Ané JM, Kiss GB, Riely BK, Penmetsa RV, Oldroyd GE, et al. (2004) Medicago truncatula DMI required for bacterial and fungal symbioses in legumes. Sci 03: 1364 -1367.

- Araujo ASF, Santos VB, Monteiro RTR (2008) Responses of soil microbial biomass and activity for practices of organic and conventional farming systems in Piauistate, Brazil. Eur J Soil Biol 44(2): 225-230.

- Bonfante P, Genre A (2010) Mechanisms underlying beneficial plant-fungus interactions in mycorrhizal symbiosis. Nat Commun 27: 1- 48.

- Buyinza, Joel, Okullo John Bosco Lamoris (2015) Threats to Conservation of Vitellaria paradoxa subsp. nilotica (Shea Butter) Tree in Nakasongola district, Central Uganda, Int Res J Environment Sci 4(1): 28-32.

- Caido M, Otim C, Kakaire D (2009) Impact of major diseases and vectors in smallholder cattle production systems in different agro-ecological zones and farming systems in Uganda. Livestock Research for Rural Development 21(9).

- Kosuta S (2003) Diffusible factor from arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi induces symbiosis-specific expression in roots of Medicago truncatula. Plant Physiol 131(3): 952–962.

- Manillet, F, Poinsot V, André O, Puech Pagès V, Haouy A, et al. (2011) Fungal lipochitooligosaccharide symbiotic signals in arbuscular mycorrhiza. Nature 469: 58–63.

- Megali L, Glauser G, Rasmann S (2013) Fertilization with beneficial micro-organisms decreases tomato defences against insect pests. Agron Sustain Dev 34: 649–656.

- Molina Favero C, Mónica Creus C, Luciana Lanteri M, Correa Aragunde N, Lombardo MC, et al. (2007) Nitric Oxide and Plant Growth Promoting Rhizobacteria: Common Features Influencing Root Growth and Development. Adv Bot Res 46: 1-33.

- Murphy JF, Zehnder GW, Schuster DJ, Sikora EJ, Polstan JE, et al. (2000) Plant growth promoting rhizobacteria mediated protection in tomato against tomato mottle virus. Plant Dis 84: 79–84.

- NEMA (2008) State of the Environment Report for Uganda. Kampala: National Environment Management Authority (NEMA).

- Ogbo FC (2010) Conversion of cassava wastes for biofertilizer production using phosphate solubilizing fungi. Bioresour Technol 101: 4120 -4124.

- Ocaido M, Otim CP, Kakaire D (2009) Impact of major diseases and vectors in smallholder cattle production systems in different agro-ecological zones and farming systems in Uganda. Livest Res Rural Dev 21(9).

- Pandey PK, Yadav SK, Singh A, Sarma BK, Mishra A, Singh HB (2012) Cross-Species Alleviation of Biotic and Abiotic Stresses by the Endophyte Pseudomonas aeruginosa PW09. J Phytopathol 160(10): 532–539.

- Paul D, Nair S (2008) Stress adaptations in a plant growth promoting Rhizobacterium (PGPR) with increasing salinity in the coastal agricultural soils. J Basic Microbiol 48(5): 1-7.

- Parrott N, Ssekyewa C, Makunike C, Ntambi S, Muwanga MK (2006) Organic Farming in Africa. In: H Willer, Y Minou (2006) The World of Organic Agriculture. Statistics and Emerging Trends. Bonn Germany, Frick Switzerland: IFOAM and Research Institute of Organic Agriculture FiBL, pp. 96-108.

- Roberts NJ, Morieri G, Kalsi G, Rose A, Stiller J, et al. (2013) Rhizobial and mycorrhizal symbioses in Lotus japonicus require lectin nucleotide phosphohydrolase, which acts upstream of calcium signalling. Plant Physiol 161: 556–567.

- Ruecker G, Park S, Ssali H, Pender J (2003) Strategic Targeting of Development Policies to a Complex Region: A GIS-Based Stratification Applied to Uganda. ZEF - Discussion Papers on Development Policy No. 69. Bonn: Centre for Development Research (ZEF).

- Sahoo RK, Ansari MW, Pradhan M, Dangar TK, Mohanty S, et al. (2014) Phenotypic and molecular characterization of efficient native Azospirillum strains from rice fields for crop improvement. Protoplasma 251(4): 943-53.

- Santos VB, Araujo SF, Leite LF, Nunes LA, Melo JW (2012) Soil microbial biomass and organic matter fractions during transition from conventional to organic farming systems. Geoderma 170: 227–231.

- Sieberer BJ, Chabaud M, Timmers AC, Monin A, Fournier J, et al. (2009) A nuclear-targeted cameleon demonstrates intranuclear Ca2+ spiking in Medicago truncatula root hairs in response to rhizobial nodulation factors. Plant Physiol 151(3): 1197-1206.

- Singh JS, Pandey VC, Singh DP (2011) Efficient soil microorganisms: a new dimension for sustainable agriculture and environmental development. Agric Ecosyst Environ 140(3-4): 339-353.

- Sinha RK, Valani D, Chauhan K, Agarwal S (2014) Embarking on a second green revolution for sustainable agriculture by vermiculture biotechnology using earthworms: reviving the dreams of Sir Charles Darwin. Int J Agric Health Saf 1: 50–64.

- Sudha M, Gowri RS, Prabhavati P, Astapriya P, Devi SY, Saranya A (2012) Production and optimization of indole-acetic-acid by indigenous micro flora using agro waste as substrate. Pakistan J Biological Sci 15: 39–43.

- Yao L, Wu Z, Zheng Y, Kaleem I, Li C (2010) Growth promotion and protection against salt stress by Pseudomonas putida Rs-198 on cotton. European J Soil Biol 46: 49–54.

- UNEP-UNCTAD (2008) Organic Agriculture and Food Security in Africa. United Nations New York and Geneva.

- UBOS, Uganda Bureau of Statistics (2014) Uganda National Household Survey 2012/13. Uganda Bureau of Statistics (Kampala, UBOS).

- Zingore SP, Mafongoya P, Myamagafota, Giller KF (2003) Nitrogen mineralization and maize yield following application of tree pruning to a sandy soil in Zimbabwe. Agroforestry Systems 57: 199-211.

-

Ayodele A Otaiku. Uganda Agriculture Human Capacity Development: Organic 3.0 Agriculture Gap and Need Analysis. World J Agri & Soil Sci. 7(3): 2021. WJASS.MS.ID.000661.

-

Biofertilizer, Biopesticide, Cattle, Cash Crops, Gap and Need Analysis, Organic 3.0 agriculture, Shea value chain development, Uganda Agriculture

-

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.