Research Article

Research Article

Date Palm Scales and Their Management

Richard Edward Turner1*, Bobby Golden2, Trent Irby3, Jeff Gore4, and Jason Bond5

11Department of Plant and Soil Sciences, University of Missouri, USA

22Department of Agronomy, Simplot, USA

3Department of Plant and Soil Sciences, Mississippi State University, USA

4Department of Agriculture and Plant Protection, Mississippi State University, USA

5Department of Plant and Soil Sciences, Mississippi State University, USA

Corresponding AuthorRichard Edward Turner, Department of Plant and Soil Sciences, University of Missouri, 147 State Hwy T Portageville, MO 63873, USA

Received Date:December 04, 2025; Published Date:December 22, 2025

Abstract

Rice (Oryza sativa L.) is predominantly grown in the U.S. Mid-South. Current Mississippi State recommendations for N fertilization of rice suggests a single application of 150 kg of N ha-1 on soils with sandier texture and 202 kg N ha-1 on clay texture soils. Our primary objective was to identify alternative N management strategies that may potentially be used to reduce cost associated with aerial application expense. Most fertilizers are applied via aircraft, a common practice in delayed-flood rice production. Research was established at the Delta Research and Extension Center, at Stoneville, MS on two soil textures during 2015 and 2016. At each location treatments were arranged in a randomized complete block design. Four nitrogen sources were evaluated and include Environmentally Smart Nitrogen (ESN), Ammonium sulfate (AMS), Diammonium Phosphate (DAP), and urea + [N-(n-butyl) thiophosphoric triamide] NBPT. Four application timings were established: at planting, 2-leaf, 7 days before flood (DBF), and midseason (MS) plus an untreated check. Data from all siteyears were pooled together for analysis to evaluate differences among N management strategy. Urea + NBPT applied in a single application 7DBF, 2-way split application, and ESN-2LF produced statistically similar and greatest mean rice grain yield. The importance of this data suggests that N fertilizer could be applied early from a ground rig prior to the levee construction; however proper timing of poly-coated urea was not established for greatest yields or economic benefit.

Introduction

A proper supply of N is required for vigorous vegetative growth, and high photosynthesis rates. The single optimum preflood nitrogen application can be described as a fertilization practice where nitrogen is applied prior to flooding to a dry soil surface with no plan for a midseason application. This method requires the yearly sum of N to be applied all at one time and immediate establish ment of the permanent flood is crucial to avoid N losses. Griggs et al., [1] reported a 31 kg N ha-1 difference in N recovery when urea is applied 14 DBF vs 1 DBF, which was likely due to ammonia volatilization. A single application of N may save expense associated with additional applications, but often additional N is required and multiple applications are needed.

The single greatest expense for rice production is nitrogen fertilizer ($308.00 ha-1) applications followed closely by herbicide ($239.00 ha-1) [2]. Urea fertilizer is the most commonly used nitrogen source in the Mid-South due to its relatively low price and its great (46%) N content; therefore, efforts should be optimized to avoid losses. Blended fertilizers are occasionally utilized such as, AMS and DAP in combination with urea. These products all contain elemental N of lower analysis than urea and are also slightly more expensive but are typically added for their nutrient analysis other than N.

The use of control release fertilizers (CRF) has grown in popularity for use in row crop agriculture since its initial use for use in vegetable production and turf industry. Due to the numerous N loss mechanisms to both the air and groundwater interest in enhanced efficiency fertilizers has increased in the row crop industry. The two most popular CRF’s are polymer coated urea (PCU) and sulfur coated urea (SCU). Polymer coated urea is manufactured by forming an insoluble polymer time release coating around each granule of urea [3]. Cost of CRF has historically been the greatest hinderance from wide scale usage in the row crop agriculture.

This research was established to determine if polymer coated urea can be utilized in delayed flood rice culture as an alternative N source for post crop emergence application. Our objective was to compare alternative N management strategies containing PCU to the standard practice of applying soluble urea with the single optimum or two-way split N management strategies. The main goal was to determine viable alternative N management practices that could extend the current N management window for rice produced with a delayed flood.

Materials and Methods

Description of Sites

Five field experiments, two in 2015 and three in 2016 were conducted to determine the influence of nitrogen management strategy on rice performance. Experiments were established in three fields at the Mississippi State University Delta Research and Extension Center near Stoneville, MS each year the experiment was conducted the experimental fields represented a silt-loam or courser textured soil and a clay soil that are commonly cropped to rice within Mississippi. In 2015, experiments were established on a Commerce very fine sandy loam, and a Tunica clay. In 2016 experiments were established on a Commerce very fine sandy loam; Bosket very fine sandy loam; and a Tunica clay.

For experiments conducted in 2015, at the Commerce very fine sandy loam site and Tunica clay site soybean [Glycine max (L.)] was the previous crop grown. For experiments conducted in 2016 rice (Oryza sativa (L.) was the previous crop grown for all sites (Commerce, Bosket, and Tunica). Eight composite soil samples (two per replicate) were collected from the 0-to 15-cm depth at each experimental site before planting. Each composite sample consisted of eight, 2.5 cm diameter cores. Soil samples were oven-dried, crushed to pass through a 2-mm sieve, and extracted with Mehlich- 3 (Mehlich, 1984). Mehlich-3 extracts were analyzed using inductively coupled atomic plasma spectroscopy (ICPS). Soil water pH was determined in a 1:2 soil weight: water volume ratio using a glass electrode.

The rice variety ‘CL 163’ was drilled into plots measuring 1.62 × 4.57-m at 18.5 kg seed ha-1. Rice variety was selected based on physical features along with disease package (CL 163; Horizon Ag, 8275 Tournament Dr Ste 255, Memphis TN 38125). Each plot consisted of eight drills of rice spaced 20-cm apart separated by a perpendicular alley 1.5-m across. To ensure no nutrients were not limiting phosphorus was applied as triple superphosphate at a rate of 45 kg ha-1 of product, potassium applied as potash at a rate of 90 kg ha-1 of product, and zinc as zinc phosphate at a rate of 6 kg ha-1 of product.

Each year, weeds were controlled with a mixture of clomazone at 0.34 kg ai ha-1 (2-(2-chlorophenyl)methyl-4,4-dimethyl-1-1,2-oxazolidin- 3-one), plus saflufenacil at 0.04 kg ai ha-1 (N’-[2-chloro- 4-fluoro-5-(3-methyl-2,6-dioxo-4-(trifluromethyl)-3,6-dihydro- 1(2H)-pyrimidinyl)benzoyl]-N-isopropyl-N-methylsulfamide), plus 0.05 kg ai ha-1 halosulfuron (methyl 3-chloro-5-[(4,6-dimethoxy- 2-pryimidinyl)amino]sulfonyl]-1-methyl-1H-pyrazole-4-carboxylate) applied to the soil surface prior to rice emergence. This was followed by a 3-5 leaf growth stage rice application mixture of imazethapyr at 0.08 kg ai ha-1 (2-[4,5-dihydro-4-methyl-4-(1-methylethyl)- 5-oxo-1H-imidazol-2-yl]-5-ethyl-3-pyridinecarboxylic acid) plus quinclorac at 1.54 kg ae ha-1 (3,7-dichloro-8-quinolinecarboxylic acid). Rice management closely followed the Mississippi State University Extension Service recommendations for stand establishment, pest management, and irrigation management.

Treatments

Nitrogen sources included ammonium sulfate (AMS; 21-0-0- 24S), polymer coated urea (PCU; 44-0-0) diammonium phosphate (DAP; 18-46-0), and urea + NBPT (46-0-0). Sources were chosen for their availability and common use in Mississippi and the Mid- South. The PCU product utilized was Environmentally Smart Nitrogen (ESN; Agrium Inc. 13131 Lake Fraser Drive S.E. Calgary, Alberta). Environmentally Smart Nitrogen is characterized by Agrium as having 80% N release at a minimum of 30 d and a maximum of 60 d (23°C) [3]. The NBPT product Agrotain Ultra (Koch Agronomic Services, 4111 East 37th St N Wichita, KS) was utilized to coat dry urea fertilizer and limit N loss from urea.

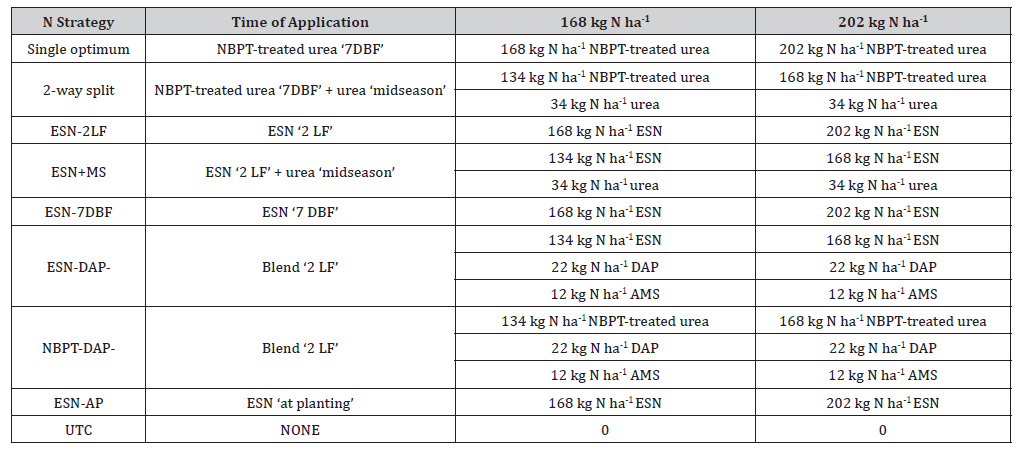

All N sources were broadcast by hand to randomly assigned plots at total-N rates of 0, 168, and 202 kg N ha-1. Applications for N sources were applied at planting, 2 leaf, 7 DBF, and at Panicle Differentiation (PD) growth stage (Table 1).

Single optimum N management strategy (single application of urea + NBPT) and 2-way split (application of urea + NBPT applied at 7DBF plus a midseason urea application) are university recommendations fertilizer N management strategies. Rate of N ha-1 being applied per strategy is represented.

Measurements

Aboveground rice biomass was collected in a 1 m length of the second or seventh drill path row. Plant samples were harvested by hand cutting the total aboveground biomass slightly above the soil surface at panicle differentiation and heading for determination of total N uptake. Plant samples were dried at 60oC, weighed, and ground. Total N concentration was determined on a subsample of plant tissue by dry combustion (Elementar Vario Mx CN, Mount Laurel, NJ: Campbell, 1992). Total N uptake was calculated using plant N concentration (%) x total dry matter accumulation (weight kg/ha-1) = N uptake ha-1.

Table 1:Nitrogen management strategy with respect to time of application and amount of N applied for each soil type during the 2015 and 2016 at the Delta Research and Extension Center.

After collection, aboveground portions of rice plants were oven- dried and mass for each sample was determined using a calibrated Denver Instrument Company XE series model 400 balance (Denver Instrument Company, 5 Orville Dr.; Bohemia, NY). From the HDG aboveground biomass sample, number of tillers per 1 m sample were collected. Harvest samples were collected at the time of harvest and from this sample a sub-sample was collected to determine milling quality of each treatment. The samples were hulled in a huller, milled in a McGill miller, and broken kernels were removed in order to determine milling yield [4]. Milled Rice Yield = (Milled Rice/Rough Rice)*100; Head Rice Yield = (Head Rice/ Rough Rice)*100.

After collection, aboveground portions of rice plants were oven- dried and mass for each sample was determined using a calibrated Denver Instrument Company XE series model 400 balance (Denver Instrument Company, 5 Orville Dr.; Bohemia, NY). From the HDG aboveground biomass sample, number of tillers per 1 m sample were collected. Harvest samples were collected at the time of harvest and from this sample a sub-sample was collected to determine milling quality of each treatment. The samples were hulled in a huller, milled in a McGill miller, and broken kernels were removed in order to determine milling yield [4]. Milled Rice Yield = (Milled Rice/Rough Rice)*100; Head Rice Yield = (Head Rice/ Rough Rice)*100.

Statistics

Individual experiments were designed as a randomized complete block with a 10-treatment arrangement. Each treatment was replicated four times. Means for rice grain yield, total aboveground biomass, and yield component data were calculated across replicates for each site year. Type III statistics were used to test treatment effects, and least square means were separated at the P < 0.05 significance level.

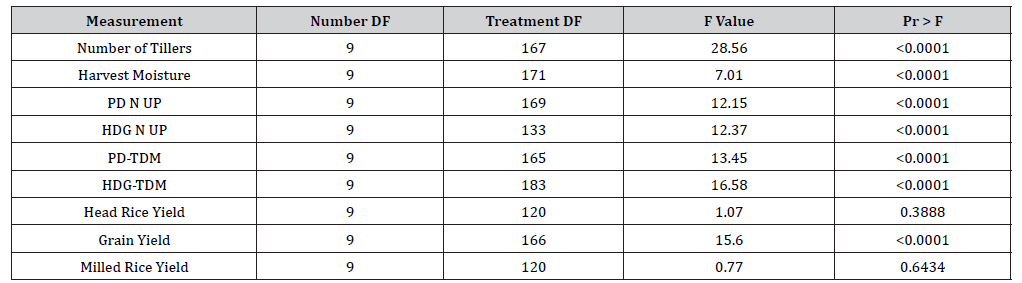

Classified by site year, data was subjected to ANOVA using the PROC MIXED procedure in SAS v. 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc. 100 SAS Campus Drive Cary, NC 27513-2414, USA). Least square means were calculated, and mean separation (p < 0.05) was produced using PDMIX800 in SAS (Table 2), a macro for converting mean separation output to letter groupings [5].

Results and Discussion

Total Aboveground Biomass and N Uptake

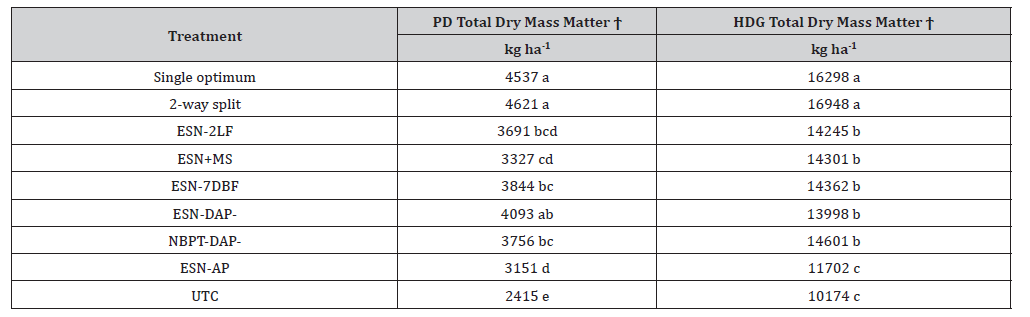

Panicle Differentiation: Aboveground rice biomass differed among N application strategies (Table 2). Averaged across all siteyears total above ground biomass was greatest with the 2-way split (NBPT+MS) (4621 kg ha-1), but similar to the single optimum (NBPT-7DBF) (4537 kg ha-1) and ESN-DAP applied at the 2-LF growth stage (4093 kg ha-1) (Table 3). However, the similar results between the 2-LF ESN-DAP applications suggest that based on biomass alone, the window for N fertilization may widen with the use of a PCU in combination with a small amount of readily available nitrogen (i.e. 34 kg N ha-1 supplied as DAP and AMS). Previous research suggests the majority of N applied prior to flooding is recovered by PD [6-8]. ESN-AP produced significantly greater total dry matter (TDM) than the untreated check but yielded similar biomass to rice that received the ESN-2lf and ESN+MS application management strategy (Table 3).

Table 2:Analysis of variance p-values table for each measure taken during the 2015 and 2016 at the Delta Research and Extension Center.

Table 3:The main effect of total dry mass matter at two timings (panicle differentiation and heading) influenced by treatment for research pooled across all site years during the 2015 and 2016 at the Delta Research and Extension Center.

Ϯ (Means within a column followed by the same letter are not significantly different at P ≤ 0.05)

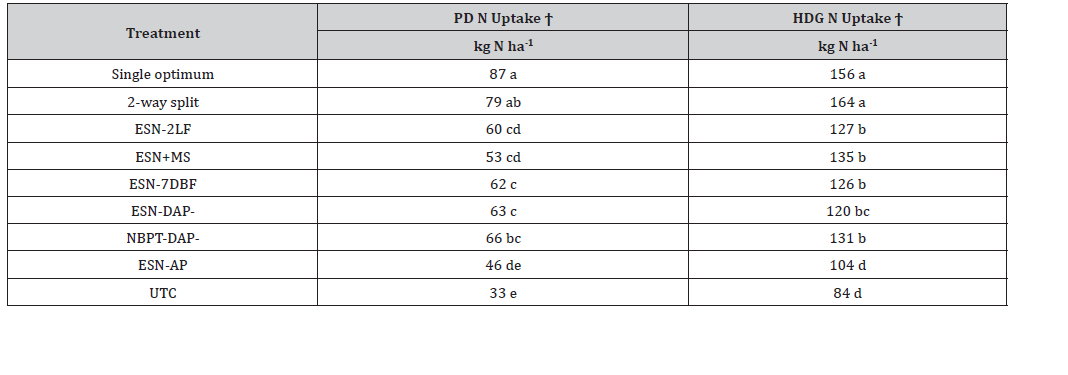

The single optimum (87 kg N ha-1) and 2-way split application (79 kg N ha-1) produced the greatest N uptake which differed from all other N application management strategies (Table 2). Nitrogen uptake was similar among NBPT-DAP (66 kg N ha-1), ESN-2lf, ESN+MS, ESN-DAP, and ESN-7DBF, and greater than the untreated control and ESN-AP (Table 4). Carreres et al., [9] noted that N recovery from preflood applied PCU ranged from 45-62 kg N ha-1 depending on percent of PCU being utilized. Nitrogen uptake at PD from rice receiving ESN-AP (46 kg N ha-1) and the untreated check (33 kg N ha-1) was similar. Golden et al., [10] reported that N uptake at PD differed among siteyears, N sources, and sample times; similarly, this data also revealed a difference in sources and application timing. All N management strategies that contained PCU (2-LF and 7DBF) produced significantly lower N uptakes than either N management strategies containing urea N applied 7DBF.

Heading: Nitrogen uptake at HDG is crucial because N has reached the maximum accumulation in the plant [8]. Nitrogen application via 2-way split was similar to rice receiving N with the single optimum preflood strategy (Table 4). The trend for TDM parallels to that of N uptake at both PD and HDG. Similarly, Wilson et al., [11] showed the importance of preflood N, and its relationship with TDM accumulation and N uptake.

Table 4:The main effect of N uptake at two timings (panicle differentiation and heading) influenced by treatment for research pooled across all site years during the 2015 and 2016 at the Delta Research and Extension Center.

Ϯ (Means within a column followed by the same letter are not significantly different at P ≤ 0.05)

All N applied at 2-LF as well as the ESN-7DBF produced similar N uptake. All N management strategies produced greater N uptake when compared to rice that received N with the ESN-AP method. N uptake, at both PD and HDG from rice receiving N at planting as ESN was inferior to all other management strategies. (Table 4). Heading N uptake was 33% less for ESN applied at planting compared to single optimum and 46% less when UTC was compared to single optimum. Golden et al., [10] reported similar results with UTC performing 73% less and ESN at planting 46% less than urea. Nitrogen uptake was significantly greatest when the 2-way split and/or single optimum preflood N management strategies was utilized (164 kg N ha-1), Norman et al., (2009) reported similar results from rice receiving preflood NBPT treated urea applied 10 DBF. Differences in N recovery occurred due to the extended days before flooding so N losses likely occurred. This shows the importance of a timely flood; minimum losses occur within 7 d which is why PCU could be utilized if delayed flood occurred.

All treatments produced greater N uptake at heading compared to the untreated check except ESN-AP (Table 4). Golden et al., (2009) showed similar results comparing ESN-AP and untreated check, his observations were ESN-AP (100 kg N ha-1) and UTC (50 kg N ha-1). This data suggests that the ESN applied at planting is too early of an application in delay-flooded rice production and N losses occurred post flood via denitrification. Rice receiving ESN fertilization at either 2-LF or 7DBF produced similar N uptake. The ESN-7DBF likely was applied too late, the slow-release nature of the product would not have allowed the bulk of N to become available till after PD.

Table 5:The main effect of harvest moisture, number of tillers, and grain yield influenced by treatment for research pooled across all site years during the 2015 and 2016 at the Delta Research and Extension Center.

Ϯ (Means within a column followed by the same letter are not significantly different at P ≤ 0.05)

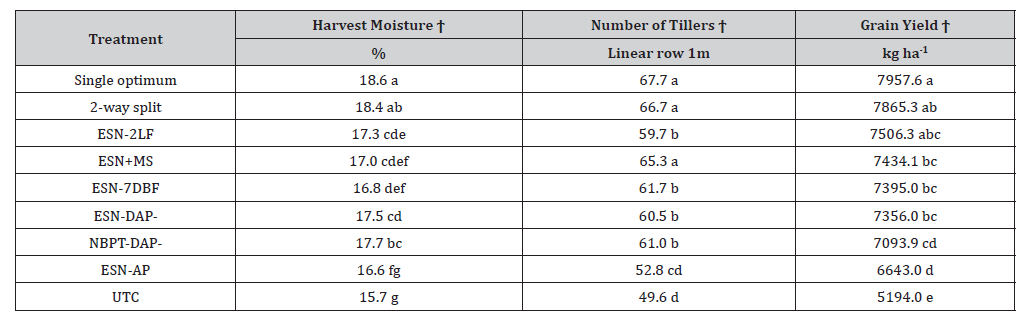

Tillers: Number of tillers (Table 2) was significantly influenced by N when compared to the untreated check (50) except ESN-AP (53). Single optimum (68), 2-way split (67), and ESN+MS (65) application produced significantly the most tillers (Table 5). Nitrogen source may have influenced number of tillers because three of four treatments receiving urea + NBPT produced significantly the greatest. Nitrogen fertilization that occurs at or near panicle formation has been reported to increase number of spikelet’s [12,13]. A strong linear relationship between number of tillers and grain yield occurred; therefore, number of tillers was correlated to yield potential. If number of tillers is statistically similar among strategy but different among grain yield, then the N management strategy must have had an effect on filled grains per panicle or grain weight. Number of panicle-2, grain weight, and filled grains per panicle decreased with the use of ammonium sulfate [9].

Overall, this data suggests that in order to maximize number of tillers then a readily available N source should be applied at or near PI. From this data, urea as a source of N produced greater number of tillers when applied at 7DBF compared to PCU regardless of when PCU management strategy occurred.

Grain Yield: All management strategies receiving N fertilization produced significantly greater grain yield than the untreated check (5194 kg ha-1) (Table 2). Single optimum (7958 kg ha-1), 2-way split (7865 kg ha-1), and ESN-2lf (7506 kg ha-1) produced the greatest grain yield (Table 5). Nitrogen recovery was not significant between single optimum and 2-way split; therefore, the midseason urea application was not economically advantageous due to a lack in grain increase but increased cost. Slaton et al., [14] showed urea applied pre-flood yielded approximately 7535 kg ha-1, which was similar results to single optimum; however, PCU applied at 2lf growth stage produced significantly greater yields (at 38% PCU-N). 2-way split midseason urea application only beneficial aspect although not significant was HDG total dry matter (Table 3). Similar results were observed by Reddy and Patrick [15] when they noted a relationship between N uptake and grain yield.

ESN+MS, ESN-7DBF, ESN-DAP at two leaf growth stage all produced similar yields as the 2-way split and ESN-2lf. Previous research has shown that yield potential is determined by the preflood N application [11,16,17] and maximum yields are obtained when N is applied to dry soil and flooded immediately [17-19]. Both ESN-AP and NBPT-DAP produced similar grain yields (Table 5).

Clark et al., [20] showed that urea only outperformed AMS when the flood could be immediately applied; however, AMS could be a better source of N if flooding was delayed more than seven days due to a lack in volatilization losses. Bufogle et al., [21] also reported the similarity that urea and AMS are being equally efficient. Due to the low N analysis of AMS many more products would be needed to achieve < 168 kg N ha-1. Unless sulfur is needed urea should remain the N source of choice to achieve maximum grain yields.

Summary

The ultimate goal of this research was to evaluate alternative N management strategies that could extend the N management window on rice produced with a delayed flood in the Mississippi Delta. Research conducted compared the influence of N fertilizer additions on two commonly cropped soils in Mississippi. Nitrogen strategy significantly affected several potential yield indicator variables such as aboveground biomass, N uptake, and number of tillers.

Total aboveground biomass was influenced by N management strategy at both PD and HDG. All N management strategies that contained urea + NBPT produced significantly greater TDM regardless of application timing. Urea based management strategies outperformed ESN based management strategies in all yield indicator variables including number of viable tillers, TDM and N uptake.

A few authors have reported that ESN has promised rice production [10,14,22]. Our research suggests that PCU management strategies need to be altered to be effective in dry seeded, delayed flood culture. In this research we observed rice yields produced with PCU management strategies ranging from 6 to 17 % less than yields achieved with the standards of single optimum preflood and 2-way split application strategies. The slow-release nature of ESN did not perform as well as urea in the aquatic nature of rice production or proper timing of application for this product is yet to be determined. Reduced grain yield produced from PCU may contribute to offsite fertilizer granular movement, which was observed during permanent flood establishment [23-25].

Acknowledgement

None.

Conflict of Interest

No conflict of interest.

References

- Griggs BR, RJ Norman, CE Wilson Jr, NA Slaton (2007) Ammonia volatilization and nitrogen uptake for conventional and conservation tilled dry-seeded, delayed-flood rice. Soil Sci Soc Am J 71: 745-751.

- USDA (2014) Cost and Returns. June 24, 2015.

- Agrium US Inc (2004) ESN polymer coated urea. MSDS no. 14250. 21 Oct. 2004. Agrium U.S. Inc., Denver, CO.

- Bautista RC, TJ Siebenmorgen (2002) Evaluation of laboratory mills for milling small samples of rice. Appl Eng Agric 18: 577-583.

- Saxton AM (1998) A macro for converting mean separation output to letter grouping in ProcMixed. Pages 1243-1246 in: Proceedings of the 23rd SAS users Group International. Car, NC: SAS Institute.

- Brandon DM, BR Wells (1986) Improving nitrogen fertilization in mechanized rice culture, pp. 161-170. In: S.K. De Datta and W.H. Patrick, Jr. (eds.), Nitrogen Economy of Flooded Rice Soils. Martinus Nijhoff/Dr. W. Junk Publishers, Dordrecht, The Netherlands.

- Bufogle Jr A, PK Bollich, JL Kovar, CW Lindau, RE Macchiavelli (1997) Rice plant growth and nitrogen accumulation from a midseason application. J Plant Nutr 20: 1191-1201.

- Wilson CE Jr, RJ Norman, BR Wells (1989) Seasonal uptake patterns of fertilizer nitrogen applied in split applications to rice. Soil Sci Soc Am J 53: 1884-1887.

- Carreres R, J Sendra, R Ballesteros, EF Valiente, A Quesada, et al. (2003) Assessment of slow release fertilizers and nitrification inhibitors in flooded rice. Biol Fertil Soils 39: 80-87.

- Golden BR, NA Slaton, RJ Norman, CE Wilson Jr, RE Delong (2009) Evaluation of polymer-coated urea for direct-seeded, delayed-flood rice production. Soil Sci Soc Am J 73: 375-383.

- Wilson CE, PK Bollich, RJ Norman (1998) Nitrogen application timing effects on nitrogen efficiency of dry-seeded rice. Soil Sci Soc Am J 62: 959-964.

- Hasegawa T, Y Koroda, NG Seligman, T Horie (1994) Response of spikelet number to plant nitrogen concentration and dry weight in paddy rice. Agron J 86: 673-676.

- Matsushima S (1976) High-yielding rice cultivation. Japan Scientific Societies Press, Tokyo.

- Slaton NA, BR Golden, RJ Norman (2009) Rice response to urea and two polymer-coated urea fertilizers. p.211-219. B.R. Wells rice research studies 2009. Ark. Agric. Exp. Stn. Res. Ser. 591. Fayetteville, AR.

- Reddy KR, WH Patrick Jr (1980) Uptake of fertilizer nitrogen and soil nitrogen by rice using 15N-labelled nitrogen fertilizer. Plant soil 57: 375-381.

- Brandon DM, DB Mengel, FE Wilson Jr, WJ Leonards Jr (1982) Improving nitrogen efficiency in rice. Louisiana Agric 26: 4-6.

- Mengel DB, FE Wilson Jr (1988) Timing of nitrogen fertilizer for rice in relation to paddy flooding. J Prod Agric 1: 90-92.

- Norman RJ, BR Wells, RS Helms (1988) Effect of nitrogen source, application time and dicyandiamide on rice yields. J Fert. Issues 5: 76-82.

- Norman RJ, BR Wells, KAK Moldenhauer (1989) Effect of application method and dicyandiamide on urea-nitrogen-15 recovery in rice. Soil Sci Soc Am J 53: 1269-1274.

- Clark SD, RJ Norman, NA Slaton, CF Wilson (2000) Influence of nitrogen fertilizer source, application timing and rate on grain yield of rice. In: Norman RJ, Meullenet JF (eds) AAES research series 485. AES, Fayetteville, Ark., pp. 352-357.

- Bufogle A Jr, PK Bollich, JL Kovar, CW Lindau, RE Macchiavelli (1998) Comparison of ammonium sulfate and urea as nitrogen sources in rice production. J Plant Nutr 21: 1601-1614.

- Bollich PK, RP Regan, GR Romero, DM Walker (1999) Potential use of slower-lease urea in water-seeded, stale seedbed rice. In P.K. Bollich (ed.) Proc. 23rd Ann. Southern Conservation Tillage conference for sustainable Agriculture. La Agri. Exp. Stn., LSU Agricultural Center Manuscript No. 00-86-0205.

- Norman RJ, CE Wilson Jr, NA Slaton, BR Griggs, JT Bushong, et al. (2009) Nitrogen fertilizer sources and timing before flooding dry-seeded, delayed-flood rice. Soil Sci Soc Am J 73: 2184-2190.

- Norman RJ, CE Wilson Jr, NA Slaton (2003) Soil fertilization and mineral nutrition in U.S. mechanized rice culture. C. Wayne Smith and Robert H. Dilday ed. Rice origin, history technology, and production. Hoboken, New Jersey.

- Peng X, B Maharjan, C Yu, A Su, V Jin, et al. (2015) A laboratory evaluation of ammonia volatilization and nitrate leaching following nitrogen fertilizer application on a coarse-textured soil Agron J 107: 871-879.

-

Richard Edward Turner*, Bobby Golden, Trent Irby, Jeff Gore, and Jason Bond. The Influence of Nitrogen Management Strategies on Rice Performance and Yield. World J Agri & Soil Sci. 10(1): 2025. WJASS.MS.ID.000726.

-

Parlatoria blanchardi, Date palm, Green scale, Red scale, Withe scale, Palm scale

-

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.