Research Article

Research Article

Potentials of Commercialization of Smallholder Farming in Kigoma Region, Tanzania: Gross Profit Margin Analysis of selected Crops in Selected Districts, Kigoma Region

Chami Avit A*

Department of Economic Studies, The Mwalimu Nyerere Memorial Academy- Karume Campus, Zanzibar, Tanzania

Chami Avit A, Department of Economic Studies, The Mwalimu Nyerere Memorial Academy- Karume Campus, Zanzibar, P.O Box 307, Zanzibar, Tanzania.

Received Date: August 10, 2020; Published Date: September 03, 2020

Abstract

Commercialization of smallholder farming (SF) is of paramount importance for African rural economic transformation. This study was undertaken to reveal the less known potentials of commercialization of SF in Kigoma Region. The Gross Profit Margin Analysis of beans, maize and cassava in Kasulu, Kakonko and Kibondo districts from Kigoma Region was performed. Descriptive cross-sectional research design was employed and both primary and secondary data were utilized. The target population of 10,708 smallholder farmers (SFs) resulted to the sample size of 400 SFs (at 95% confidence level and 5% confidence interval (0.05 sampling error)). The study revealed majority of households were male-headed households, 57% of the households had the household size ranging from 6 to 10 members while 96.5% of all respondent’s own land. Through the overall mean yields, the study also revealed Kibondo and Kasulu as capable districts of producing both maize and beans while cassava was highly produced in Kakonko district. The study further revealed majority of SFs were non-users of improved seeds, fertilizers and pesticides. The Gross Profit Margin Analyses of all three crops revealed high profitability under ideal farming conditions compared the prevailing farmers’ traditional practices. The study concludes all opportunities in the ideal farming conditions as the major potentials for commercialization of SF. The study urges SFs, business community and the government to put deliberate efforts towards investing on the agriculture sector to enable ideal farming conditions to majority of farmers, hence enhancing agricultural productivity and profitability among SFs in Kigoma region.

Keywords: Commercialization; Smallholder Farming and Gross-Profit-Margin-Analysis

Introduction

Smallholder agriculture continues to play a key role in African agriculture. According to FAO [1] smallholder farming is the type of farming with limited resource endowments, relative to other types of farming in the agriculture sector. Approximately 80% of agriculture in sub-Saharan Africa is managed by families cultivating less than 10 hectares of land, which makes smallholder production the backbone of agriculture sector in sub-Saharan Africa [1-3]. Food supply and the livelihood of billions of people depend largely on the productivity of these systems [4]. Although smallholder farming systems have proven to be resilient and viable in risk-prone environments, climate change is likely to outpace their current coping capabilities; with less commercial opportunities in majority of areas in the world [5].

Smallholder farmers in sub-Saharan Africa have historically been confronted with numerous bottlenecks including high climate variability, low levels of income and technology, coupled with isolation from markets and lack of institutional support [1,2]. Among the widely envisaged common characteristics of smallholder farming systems include the vulnerability to changes in external conditions which result to low income producers often who do not have the means to invest in adaptive technologies and strategies under increasing climatic risks [3]. However, confronted with unprecedented risks and uncertainties, the need to incorporate new information and technologies into the traditional farming systems becomes imperative (Steenwerth et al., 2014). Taking no action towards availing commercial opportunities to the entire smallholder farming practices means jeopardizing the efforts of the past decades to improve livelihoods and reduce the number of undernourished people while enhancing farmers’ standard of living [1,6,7].

According to FAO [1], commercialization is defined as production for the market with profit objectives. Commercialization further refers to the process by which products, services, and technologies are introduced to the market for purchase (USAID, 2017). From an international development perspective, agricultural commercialization is an important pathway to providing smallholder farmers access to transformational innovations in the entire farming practice (USAID, 2017). A commercial approach to various food crops farming contrasts with subsistence farming in majority of rural areas in sub-Saharan Africa. Marketing process plays a pivotal role in the commercialization pathway. Marketing involves finding out what customers want and supplying it to them at a profit [8,9]. The fact that smallholder farmers’ empowerment decisions are based on the principles of commercialization, the need of efficient agricultural marketing systems can efficiently save the cost of exchange of agro-produce. In the agri-food systems, an efficient marketing assures adequacy and stability of food supply in ways that reward farmers, agro-traders and consumers. The major challenges underlying agricultural markets that would hamper commercialization of subsistence agriculture include poor infrastructure, inadequate support services and weak institutions, increasing transaction costs and the volatility of prices [1,10].

In Tanzania, the agriculture sector contributes 50% of the country’s GDP. The sector accounts for over 50% of the country’s exports [11-13]. Majority of Tanzanian agriculture like any other African agriculture is predominantly carried out on small-scale family farms. The big question about such family farms which are subsistence in nature is whether they can be successfully commercialized within their current structures, or whether they should give way to commercial medium and large-scale farm enterprises. In more detail, the following questions arise about the experience of commercialization of small farming in Tanzania and Africa at large and their prospects, various initiatives have been in place [14]. In all facets, commercialization of smallholder farming seems as a main vehicle in any national economic strategy to combat poverty and enhanced agricultural productivity.

Kigoma region; the region found in the North-Western Tanzania which has a rich base of land and water resources, with high crop diversity including maize, beans, cassava, rice etc [15-17]. Agriculture is mainly an economic mainstay of the Kigoma Region, with over 85% of the total population of the region depending on agriculture for its livelihood [18]. Despite the fact that maize, beans and cassava stand as the major staple crops grown by the majority of smallholder farmers in the Kigoma region, other food crops are highly grown in the region including rice, sorghum, banana, sweet potatoes, groundnut, oil palm and various fruits and vegetables. The main export crops include tobacco, coffee and cotton. Livestock kept in the target area including cattle, goats and poultry (mainly local chicken). The rationale of significant policy commitments to commercialize Tanzanian agriculture are clearly made in KILIMO KWANZA declaration [19]. Some commercialization initiatives related action points in this declaration include agricultural commoditization, implementation of incentives to ensure competitiveness and address market barriers, price stabilization mechanisms, industrialization and infrastructure development which have been advocated in the earlier times [16].

Despite the widely known challenges, roles, merits and usefulness of smallholder farming in the entire spectrum of climate change, food security and the livelihoods of smallholder farmers [1,4,20] less remains to be known on the existing potentials of commercialization of smallholder farming in Kigoma Region. This study performed Gross Profit Margin Analysis of selected three crops namely beans, maize and cassava in selected three districts namely Kasulu, Kakonko and Kibondo in Kigoma Region. The fact that, the agricultural sector in Kigoma region is dominated by smallholder farming systems which accounts for the 75% of national food production, the majority of smallholder farmers lack access to inputs, knowledge on sustainable technologies, finance, commercial markets, as well as business and market orientation [14,21]. For the sake of revealing the actual growth or decline in performance of smallholder farming particularly beans, maize and cassava in Kigoma region compared to the previous period or the industry, the Gross Profit Margin Analysis will be undertaken. The study envisaged to avail significant findings which will be useful inputs to the agricultural market actors and institutions which are at the core of agrarian revolutions which have been pursued ever since [22]. This was attributed by the three objectives; firstly to assess the average annual yield for the three crops among smallholder farmers in the study area, secondly to examine the level of adoption of modern farming methods among smallholder farmers in the study area and thirdly was to assess profitability of maize, beans, and cassava per acre in the study area.

Methodology

Description of the study location

The study was conducted in three districts of Kigoma Region, the North-Eastern located region in Tanzania East Africa namely, Kasulu, Kakonko, and Kibondo. The selected three districts are generally from the North-Eastern part of the Kigoma region. For the sake of revealing the actual growth or decline in performance of smallholder farming in the region, three staple crops were selected namely beans, maize and cassava. Data on the said crop production were collected from three districts in Kigoma region. The Gross Profit Margin Analysis of the three selected crops of the annual production was undertaken.

Research Design

Descriptive cross-sectional research design was employed in the course of undertaking this study. The design is preferred because due to the fact that data on the variables of interest were collected and examined only once and the relationship between variables determined [23]. The design was further preferred because, it concerns with answering questions such as who, how, what, which, when and how much respondents (smallholder farmers) had accrued in the previous farming season [24]. The selected study design was found useful due to the fact that, apart from managing the data collection process to clearly avail quantitative information, the selected research design ensures minimum bias in data collection that was helpful in reducing errors in data collection process and henceforth its interpretation [25].

Types of data and collection techniques

The study gathered both primary and secondary data. Primary data were collected using a questionnaire which was selfadministered through enumerators who were deployed to gather data from the smallholder farmers in the designated study area. Other sources of primary data were value chain players including agro-dealers, operators of aggregation centers, processors and various financial service providers. These stakeholders were consulted through scheduled interviews which were guided by checklists of issues related to their thematic areas of operations. Secondary data were collected through desk review of different reports including various agriculture project documents, progress reports; government documents and several other reports from district extension officers and relevant literature from regional and district levels. Data was largely collected through close ended questionnaire which was self-administered through enumerators. Nine enumerators were deployed into collecting data across the three target districts. The data were then imported to Excel and SPSS software for cleaning analysis.

Sampling technique

This study employed random sampling technique. A multistage cluster sampling technique was applied where the population of target farmers was first clustered into three target districts, then into wards according to the proportion of farmers in each district and ward. The individual farmers, organized in groups at ward level, were then randomly selected from villages to ensure that each had equal chance of being selected.

Sample size and distribution of farmers

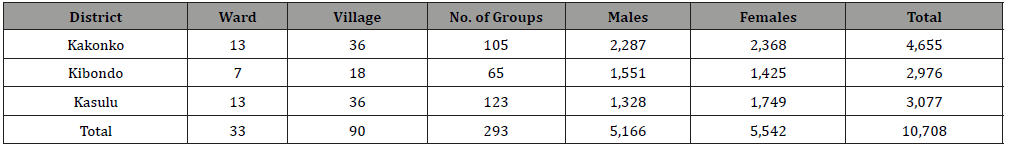

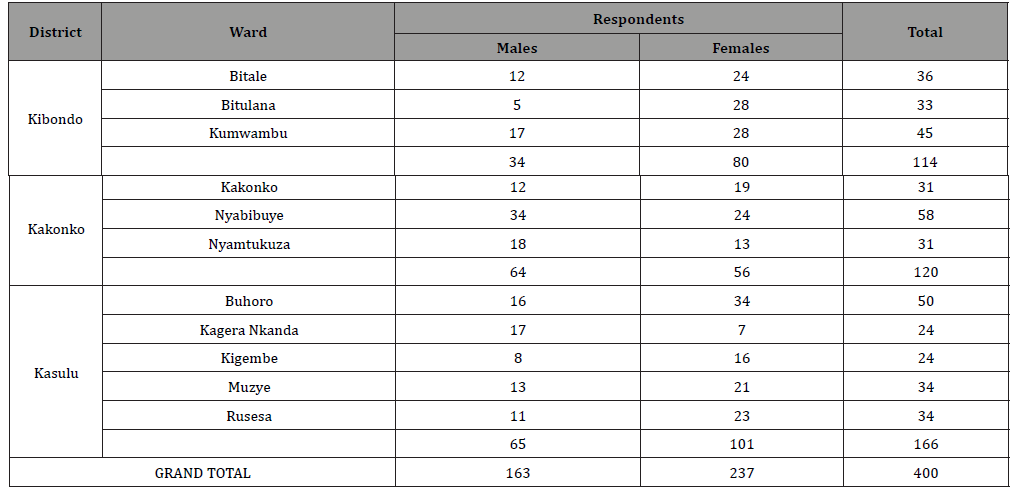

The sampling frame of the study was the list of all smallholder farmers in the three districts namely Kibondo, Kakonko and Kasulu. From the target population of 10,708 smallholder farmers (listed in groups by various intervention projects had been carried out in the selected districts), the sample size was determined to be 371 individual farmers (at 95% confidence level and 5% confidence interval (0.05 sampling error)). The sample was weighted, and farmers apportioned to districts according to their numbers per district (Table 1). Working out the calculation (last column), the proportions of farmers allocated to Kakonko, Kibondo and Kasulu were 43%, 28% and 29% respectively, which is similar to 161 framers in Kakonko, 103 in Kibondo and 107 in Kasulu.

The respective number of farmers per district was changed from the original plan to that indicated in Table 2: 114 farmers in Kibondo, 120 in Kakonko and 166 in Kasulu. The sample was increased by almost 8% to 400 farmers above the planned 371 farmers to take care of potential missing data. The distribution of farmers who were interviewed in three districts is presented in the Table 2.

Table 1: Distribution of smallholder farmers’ population and their groups in three districts.

Table 2: Distribution of farmers interviewed in three districts.

Data analysis

Data analysis for each perspective was aided by the application of Microsoft Excel and Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS 22.0) computer programs. Analysis entailed descriptive statistics which generated frequencies/percentage and means for the required information. Qualitative data were mainly used to triangulate quantitative information. In particular Gross Profit Margin Analysis (GMA per acre) was undertaken. The fact that gross profit can be used as a proxy for assessing land productivity, the test assumes all (100%) of the harvested crop was sold at the market. The revealed findings on profitability of maize, beans, and cassava respectively per acre were calculated by consultations with field extension staff, taking practical data from smallholder farmers themselves. Gross Profit Margin Analysis considered two sides; namely ideal farming conditions (demo plots) and farming practice in the study area.

Results and Discussion

The results and discussion section entails basing findings regarding the potential and useful demographic attributes of the study respondents as well as the designated three study objectives. The findings on the first objective which was meant to assess the average annual yield for the three crops among smallholder farmers in the study area were presented in line with other findings for second and third objective; to examine the level of adoption of modern farming methods among smallholder farmers in the study area and to assess profitability of maize, beans, and cassava per acre in the study area respectively.

Characteristics of respondents

The useful socio-economic characteristics of the 400 respondents who were involved in this study namely sex, household size and Ownership and access to land among smallholder farmers in the study area. The respondents’ relevant characteristics were sought important in providing a snapshot on the background of the respondents and their suitability for this inquiry. The characteristics are summarized, presented in percent using bar charts and possible implications to the populations discussed in the following subsections.

Sex of respondents: Most of the households were male headed. Overall, 82.5% of households were headed by men and 17.5% by women. The female household heads indicated either that they were divorced, widowed, unmarried or married to polygamous husbands. Variation in three districts surveyed was visible. For example, there were more female-headed households in Kibondo (28.5%), followed by Kakonko (19.7%) and Kasulu (10.8%). Traditionally, households in the three districts are headed by males. Female-headed households are fewer and considered abnormal in this community.

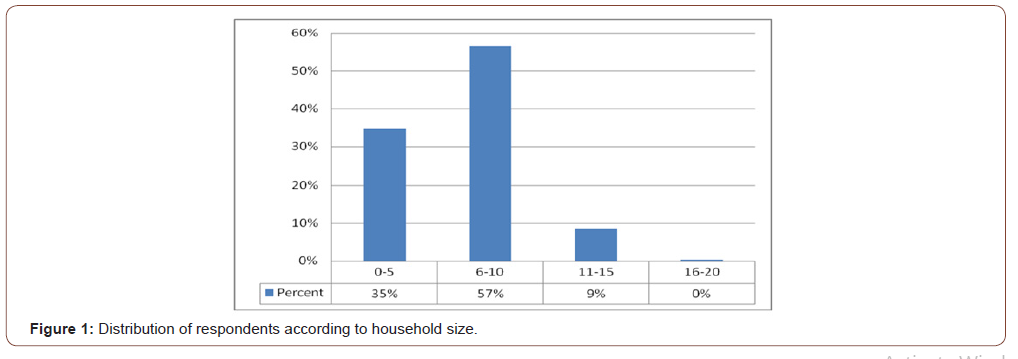

Household size: It was found, among interviewed households that, household size ranged from 1 to 16 members, with an average of 7 persons per household. Most of the households (57%) had members ranging from 6 to 10 and 0 to 5 members (35%). Only a few households (about 9%) had over 10 members. Figure 2 depicts the general picture of household size in the three districts (Figure 1).

The household sizes differences among districts can be drawn from the study findings as follows: Kasulu had more households with family size ranging from 0 to 5 years (7.3%); while Kakonko had the largest number of households with 6 to 10 members (12.6%). The same district also had a relatively large number of household sizes above 10.

Ownership and access to land among smallholder farmers: In terms of land ownership, about 96.5% of the interviewed respondents indicated that they own land; 1.2% reported that they both owned and hired land and the remaining 2.3% indicated that they don’t own land but share the land with others such as their parents, other relatives, and friends. In terms of access, all interviewed respondents indicated that they have access to agricultural land. No farmers failed to grow crops because of the lack of access to land. The size varied widely as some farmers owned small areas such as 1 acre (0.4 hectares) while only 2 farmers mentioned to having above 60 acres. However, the mean was 5.3 acres (2.12 hectares). The ownership among districts did not differ much from general ownership; only 3.6% and 2.4% of farmers in Kibondo and Kasulu respectively said that they share ownership with others. There was no big difference in land ownership by sex; about 98.8% of males owned land while 96.6% of females indicated that they own land.

Average annual yield for the three crops among smallholder farmers

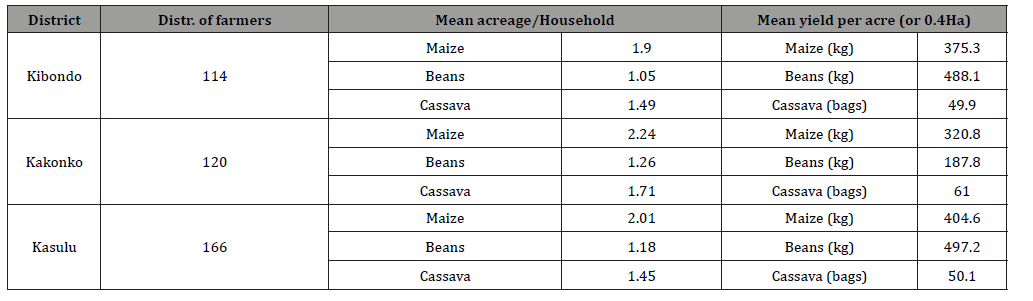

In the course of underscoring the effective participation of smallholder farmers in agricultural activities in the study area, the average annual yield for the three selected crops namely maize, cassava and beans in three districts were revealed. Crop yield per unit area is key productivity index. The average yield values for the three crops are indicated in Table 3. The presented data in the Table has disaggregated yields of the three crops per district. However, the overall mean yields of maize, beans and cassava for the three districts are 371 kg, 400 kg, and 53 kg per acre respectively.

With exception of beans, the yields in Table 3 are below the average figures cited in literature and those recommended by local extension staff. An average yield of maize in Kigoma ranges from 1200 to 1600 kg per ha (480 to 640 kg per acre) [5]. However, discussions with local extension staff in the three target districts indicated that the average yield of maize ranges between 2,000 and 2,500 kg per acre depending on the variety planted.

Table 3: Acreage and yield of maize, beans and cassava for target districts.

In beans, FAOSTAT (2006) showed the average yield for Tanzania is 741 kg/ha which is a little bit below Africa’s average (799 kg/ha). This national average is equivalent to 296.4kg/acre, which is less than the average yield of beans reported in Table 3. With exception of Kakonko, the average yield of beans in the target districts seems to be higher than the National average. The widely planted Kigoma yellow variety produces an average of 715 Kg/Ha, while the highest producing variety, Lyamungu 90, produces 1,430 Kg/Ha under the same conditions [18].

In cassava, it is estimated that, under ideal conditions, cassava varieties yield up to 7 MT per ha or 2.8 MT/acre [5]. Discussion with local extension staff indicated that under ideal field conditions as per demo plots, cassava gives yield of up to 300 bags (of 90 kg each) per acre. The yield figures are below this average regional figure.

Level of adoption of modern farming methods among smallholder farmers

The fact that more than 80% of Tanzania’s population depends on climate sensitive rain-fed agriculture as a source of livelihood, these smallholder farmers who control a large part of the country’s agricultural production are currently experiencing adverse climate change impacts due to traditional methods in their farming practices [15]. The understanding of the level of adoption of modern farming methods among smallholder farmers in the study area can help in reducing vulnerability of the agriculture sector hence envisaged to significantly contribute to socio-economic development and ensure food security among the farming communities. In the course of shedding light on the level of adoption of modern farming methods among smallholder farmers in the study area three parameters were put forward mainly; the application of primary farm inputs including improved seeds, fertilizers and pesticides.

The fact that demonstration of modern farming methods implies mostly the application of farm inputs in the farming practice stands as one of the key factors for increasing farm productivity (yield). According to agro-dealers in three districts, inputs required by most farmers in the project area include seed, fertilizers and pesticides. Most farmers use traditional seed, there is limited tendency to buy improved seeds. The role of input suppliers in production is mainly limited to agro-chemicals. Farmers use seeds kept from the previous harvest or buy from fellow farmers who could store enough to sell, or from food kiosks. There are no improved, certified, beans seed sold by any of the village input suppliers interviewed. Farm inputs may also refer to tools, equipment and technologies which are used to enhance the effectiveness of farm operations. The study found out that most farmers across the three target districts practice low-input agriculture which is characterized by no or inadequate use of recommended inputs. Based on the study findings; three parameters were put forward; the use of the primary farm inputs including improved seeds, fertilizers and pesticides.

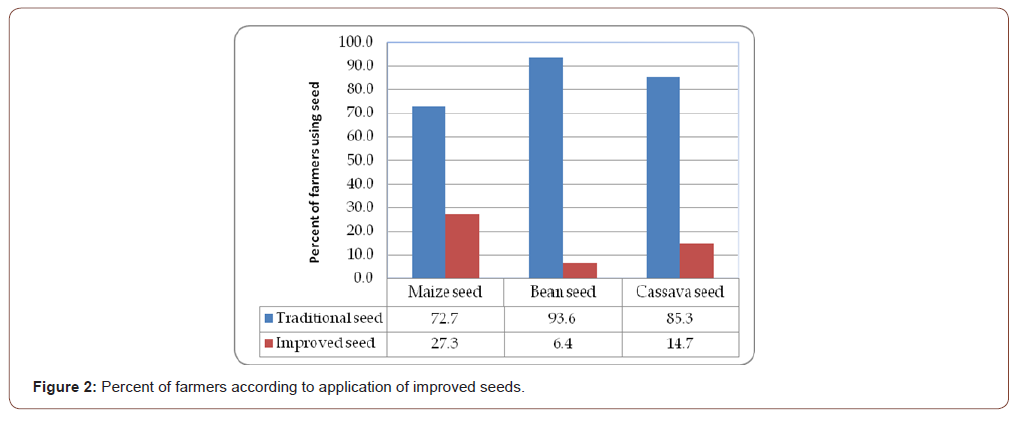

Prevalence of application of improved seed against traditional seeds: Figure 2 shows that about 72.7% of maize farmers used traditional maize seeds, 93.6% and 85.3% of bean and cassava farmers respectively use traditional seeds. This means that the majority of maize farmers use traditional seeds.

Traditional (indigenous) low-yielding verities generally have inferior genetic potential in terms of yield, time to maturity and susceptibility to diseases and pests. In this era of climate adversity which is associated with short rains, high prevalence of plant pests and diseases and degrading soil, farmers need to use improved seed varieties because most of them are adaptive or resilient to these adverse effects of climate change (Figure 2).

• Maize: USAID (2014) saw that although improved maize hybrids have diffused rapidly in high potential areas of Tanzania, a large proportion of resource-poor farmers in marginal areas still use local varieties and prefer improved open-pollinated varieties (OPVs) over hybrids. Recent reports estimate the area under improved OPVs to be 9% (USAID, 2014).

• Beans: In terms of variety preference, farmers in Kigoma seem to prefer Lyamungo 90 and Jesca beans. The reasons given by farmers are high yielding and short cooking time. These traits need to be incorporated into the breeding processes. A study by Bucheyeki & Mmbaga [18] indicated that Kigoma yellow rank last in terms of yield. The common bean varieties available include Lyamungo 90, Jesca, Uyole 94, Kablanketi and Kigoma yellow. Despite lowest yield, farmers seem to prefer Kigoma yellow because it suits Kigoma agro-climatic conditions long and short cropping seasons. It can be planted in both seasons. Under traditional planting practice, bean farmers’ plant in lines or broadcast. They sow 3-4 debe1 per acre (each debe weighs 20-21 kg). Unlike in past years, currently, farmers have started planting using fertilizers.

1Swahili word for a metallic (tin) container, usually measuring 20 liters

• Cassava: Despite the release of several new cassava varieties, cassava landraces remain predominant in Kigoma. Most farmers still grow traditional varieties and practice recycling. It is estimated that only 2% of cassava is planted with improved planting materials while 98% is planted with recycled or shared cuttings. This practice has led to severe yield decline due to the spread of diseases, especially Cassava Brown Streak Disease (CBSD) and Cassava Mosaic Disease (CMD) which are common in most of the cassava growing ecologies.

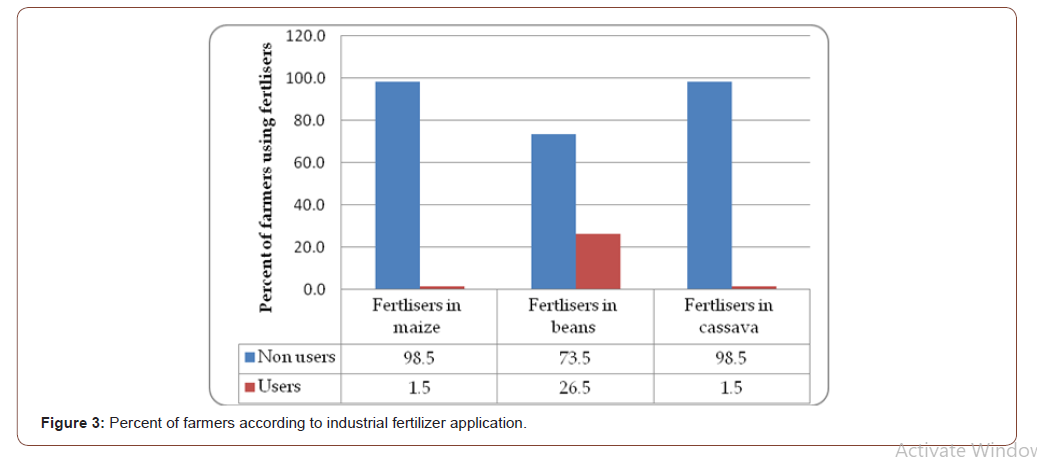

Fertilizer: Results indicate that the majority of farmers are non-users. From Figure 3, only 1.5% of farmers indicated that they use fertilizers, while 26.5% and 1.5% of bean and cassava farmers respectively indicated that they use fertilizers. As majority of target community does not keep livestock; use of organic fertilizers is also uncommon. The fewer farmers who apply fertilizers don’t use the recommended rates resulting into low crop productivity

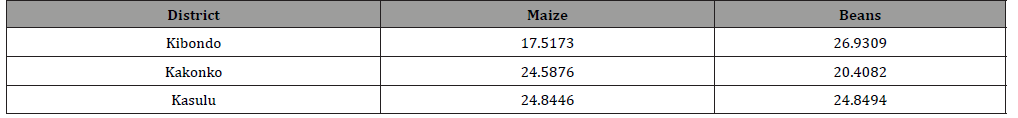

In terms of amount of fertilizers applied, maize farmers used an average of 22 kg/ha (range 0 to 250 kg per hectare); bean farmers used and average of 24 kg/ha (range 0 to 500 kg/ha). These are lower application rates. According to local extension staff, the recommended application rate in both maize and bean crop is 125 kg/ha for both planting and topdressing. This rate is applicable for both phosphate (planting) and nitrogenous (top-dressing) fertilizers. Generally, farmers don’t use fertilizers in cassava farms. Table 4 shows use of fertilizers disaggregated per district.

Pesticide application: Similarly, the study identified that most farmers don’t use pesticides. Low or non-use of pesticides results into crop loss due to the vulnerability of crop plants to pest attacks. Farmers indicated that there were pests and diseases that attack their crops; however, there were no documented records for the last few years even from the government officials. Most of the farmers indicated that they don’t use pesticides, mainly because they are high prices of chemical pesticides; only few farmers could buy the chemical pesticides. For example, 84.8% of farmers indicated that they didn’t apply pesticides in their farm in the last farming season. At the district level, about 88.1% of farmers in Kasulu did not apply pesticides; 84.4% and 80.0% of farmers in Kakonko and Kibondo respectively indicated that they did not apply pesticides in bean and maize farms in last farming season. Some farmers indicated that they combat the challenge of pests using traditional pesticides extracted from plants such as the locally known ntibuhunwa (Tephrosia vogelii) and vitembwatembwa which may be with pepper leaves. Some farmers reported that they use same pesticides in both crops (beans and maize). The study findings indicated in Table 4 apply to only few farmers who could afford chemical fertilizers.

Table 4: Mean fertilizer use per acre in maize and beans.

In line with the study findings, the presence of agro-dealers in the study envisages the access to farm inputs among farmers. Basing on the study findings, among the three districts studied, most agrodealers are found in Kasulu. The consulted 8 agrodealers in Kasulu town were selling several agro-inputs, mainly fertilizers pesticides and herbicides. The team found only 3 agrodealers in Kakonko and 3 in Kibondo. The common characteristics of these agrodealers are the fact that they usually stock a variety of fertilizers, pesticides, and veterinary drugs. Pesticides are widely used, to control farm insects or during post-harvest handling (storage) to control insects such as Stophilus trancatus.

The primary farm inputs, in essence, include improved seeds, fertilizers and pesticides. Farm inputs may also refer to tools, equipment and technologies which are used to enhance the effectiveness of farm operations. The study found out that most farmers across the three target districts practice low-input agriculture which is characterized by no or inadequate use of recommended inputs. In line with the findings from Rwehumbiza [21] that in order to improve the productivity of smallholder farming there is need for government to subsidize and enhance the availability of inputs mainly farm inputs. However, it is impetus to train, equip and deploy adequate numbers of extension officers and land use planners at grass root level to reduce unplanned land management improper farming practices.

Profitability of maize, beans, and cassava per acre

Gross profit can be used as a proxy for assessing land productivity. This assumes all (100%) of the harvested crop was sold at the market. This can give a smallholder farmer deeper insight into farming practice management efficiency. In the course of revealing gross margin profit, the ideal conditions were calculated with the aid of field extension staff as well as taking practical data from demo plots. The study findings presented in Tables 5, 6 and 7 show profitability of maize, beans, and cassava respectively per acre under ideal (demo plots) and farmer conditions (as recorded during the undertaking of study) [26]. Basing on the study context, the ideal conditions refer to the plots which accessed all necessary farm inputs during the whole season while farmer condition data where the collected information from the common farming practice from the study area.

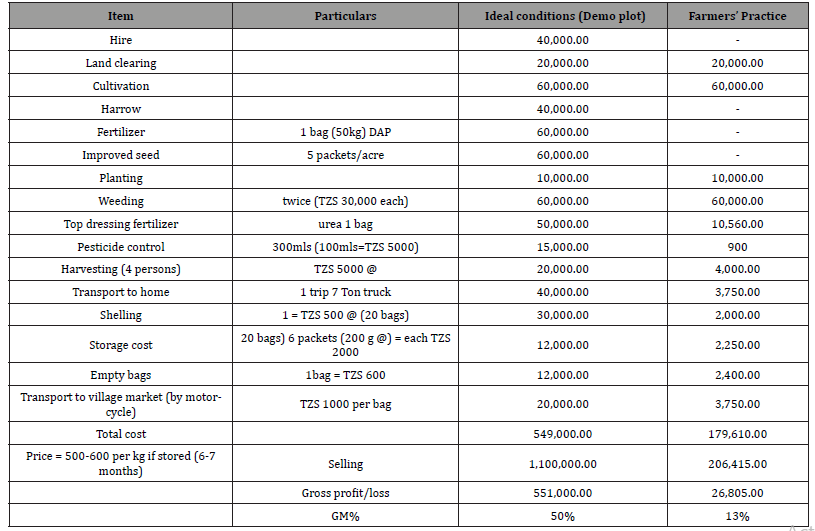

Table 5: Gross Profit Margin Analysis for Maize.

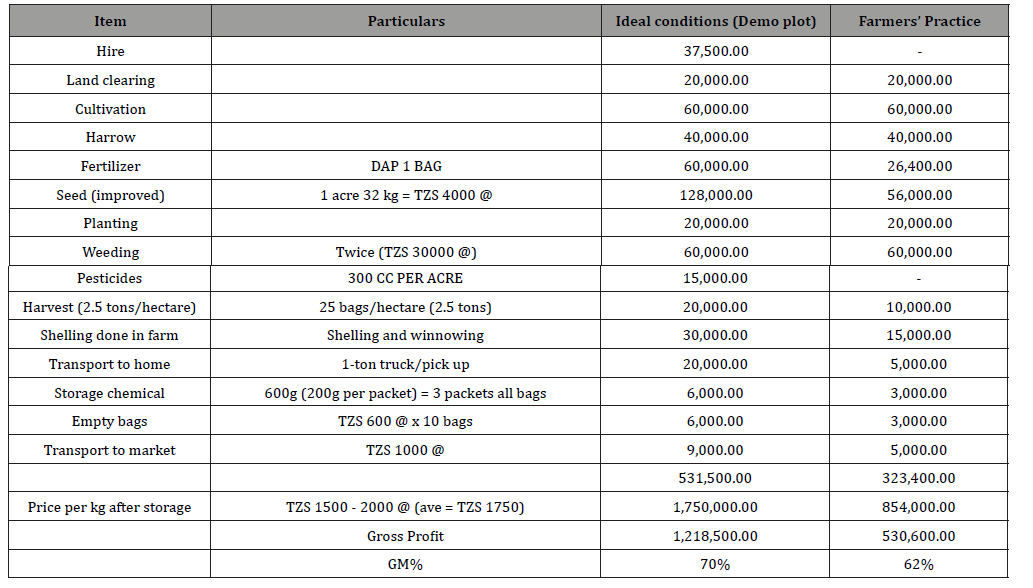

Table 6: Gross Profit Margin Analysis per acre – Beans.

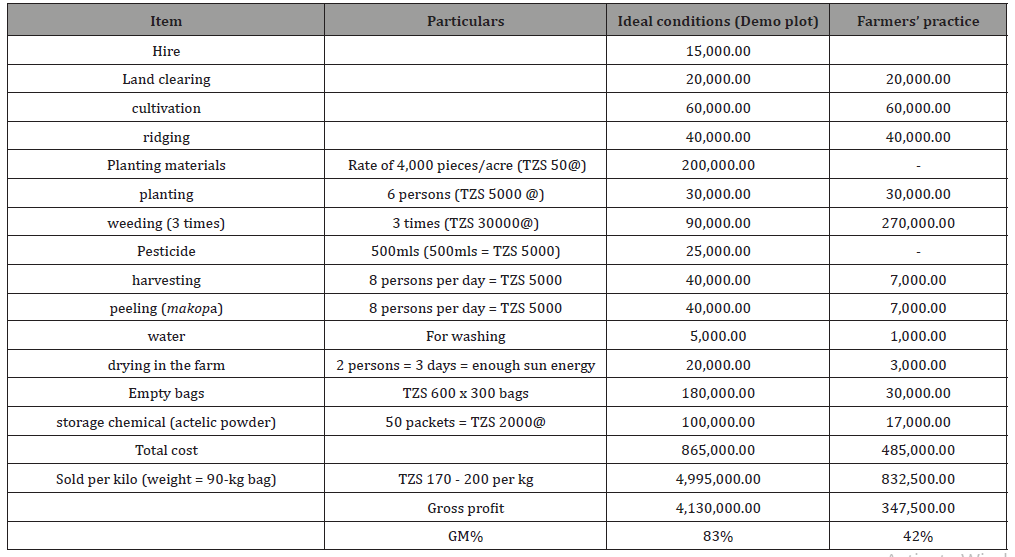

Table 7: Gross Profit Margin Analysis per acre - Cassava.

Gross profit margin analysis for maize: Maize (Zea mays, L.) is the main staple crop in Tanzania and Kigoma in particular. Food security information indicates that maize is the main staple and source of calories (carbohydrate) in the Kigoma region. Overall, 98.8% of farmers indicated that they grow maize in the last farming season. District data show that about 97.6% of farmers in Kasulu grew maize; 99.1% in Kibondo and all farmers (100%) in Kakonko grew maize in the last farming season. Majority of maize farmers were reported to sell maize as whole grains, packaged in bags, unpackaged flour or packaged flour.

The gross profit margin per acre of maize under ideal practices recommended by extension staff could be 50% per acre. However, under farmers’ condition, it is about 13% per acre. Farmers still have a long way to go to attain the ideal gross margin.

Gross profit margin analysis for beans: Bean (Phaseolus vulgaris, L.) is the main protein source in the three districts. The production of beans in the target districts is characteristically dominated by smallholder farmers. Beans in the target districts are a critical crop for two reasons: first, it is the main supplier of protein and second, it is a source of income. It is estimated that about 50% of small-scale farmers do intercrop beans with maize or cassava, usually in the first season and grow the crop in monoculture during the second season. In terms of yield, pure stands are better than the intercropped crop. Through Gross Profit Margin Analysis for beans could inform the potential area for investment. The two sides of the collected data including demo plots with ideal conditions compared to farmers traditional farming conditions. By undertaking the gross margin per acre is higher for ideal farming practices, as demonstrated in demo plots. The findings in the Table 6 entail Gross Profit Margin Analysis of beans under ideal conditions was about 70% as opposed to bean farming under farmers’ conditions. Similarly, the ideal production figures as demonstrated at demonstration plots showed a great difference from farmers’ real practice on the ground.

Like maize, the gross margin per acre is higher for ideal farming practices, as demonstrated in demo plots. Since beans production under ideal conditions was about 70% as opposed to bean farming under farmers’ conditions, investing in the ideal farming conditions is envisaged to be highly potential towards commercializing smallholder farming.

Gross profit margin analysis for cassava: Cassava (Manihot esculanta, L.) is the third crop, in terms of importance in Kigoma region. Cassava contributes significantly to household food security in Kigoma region. Compared to maize and beans farmers in the surveyed districts grow less cassava. Out of about 54.8% of the interviewed farmers indicated that they grow cassava. The crop seems to be grown much more in Kakonko district, where about 68.9% of farmers indicated to have planted the crop in their farm in the last farming season, compared to 53.6% and 40.9% in Kibondo and Kasulu respectively. In terms of acreage per household, the overall mean was 1.54 acres, which differed slightly from district mean acreage. For example, the largest acreage was in Kakonko where households grew an average of about 1.71 acres. Kasulu and Kibondo nearly had the same average land size; that is 1.49 acres and 1.45 acres per household respectively. Gross Profit Margin Analysis for Cassava was envisaged to be highly useful in unleashing the potential for commercialization among smallholder farmers. This could inform the ongoing initiatives towards enhancing the agriculture productivity and food security strategies in rural areas.

Similarly, GM analysis indicates that growing cassava under demo plot conditions a farmer get more profit than growing cassava under the current practice of most farmers. GM% for the ideal demo plot conditions and farmers practice on the ground was 83% and 42% - the difference is almost twice. Farmers practicing ideal farming are likely to get twice as much profit as what they get currently, hence calling for more investment in improving farming conditions.

Conclusions and Recommendations

Conclusion

Basing on the study findings, it was concluded that majority of households in the three districts are headed by males. Also, majority of the households (57%) had the household size ranging from 6 to 10 members. The study concludes that majority (96.5%) of the interviewed respondents own land. However, the concluded overall mean yields of maize, beans and cassava for the three districts are 371 kg, 400 kg, and 53 kg per acre respectively, Kibondo and Kasulu were capable of producing high quantity of maize and beans while cassava productivity was high in Kakonko district. On the other hand, the study concludes that majority of smallholder farmers were used to traditional seeds such that (72.7%) of maize farmers in the study area were reported using traditional maize seeds, 93.6% and 85.3% of bean and cassava farmers respectively use traditional seeds. This means that the majority of maize farmers use traditional seeds. Results further concluded that the majority of farmers are fertilizers non-users. Similarly, the study concluded that most farmers in the study area don’t use pesticides. Finally, the study concluded the results from the Gross Profit Margin Analyses of all three crops that; since the study findings revealed Gross Profit Margin for maize under ideal farming conditions being 50% compared to 13% that under farmers traditional practices, Gross Profit Margin for beans under ideal farming conditions being 70% compared to 62% that under farmers traditional practices while Gross Profit Margin for cassava under ideal farming conditions being 83% compared to 42% that under farmers traditional practices. Basing on the Gross Profit Margin analyses findings, the study concludes high Gross Profit Margin on all demo-plots/ideal farming conditions. High investment on farming practices including availing farming inputs on time to enable ideal farming conditions to majority of farmers was postulated as the major potential of commercialization of smallholder farming in Kigoma region.

Recommendations

Based on the study findings, the following recommendations have been put forward: -

To the smallholder farmers: They should embrace modern farming practices for enhanced agricultural productivity and profitability among smallholder farmers in Kigoma region.

• Basing on the study findings, smallholder farmers are urged to widely use improved seeds, modern fertilizers, and pesticides. This among other things could transform the current traditional farming practices into improved one with high agricultural production and productivity among smallholder farmers in Kigoma region, hence getting turned into a real commercial farming with absolute profitability.

Business community: They should enhance the availability of inputs for transforming traditional farming practices into more enhanced agricultural practices among smallholder farmers in Kigoma region.

• Basing on the study findings, inadequate agro-dealers in various areas of Kigoma including the study districts, Business community is urged to widely extend their services to a more accessible and affordable stage. This among other things could transform the current traditional farming practices into improved one with high application of improved inputs for improved agricultural production and productivity among smallholder farmers in Kigoma region, hence getting turned into a more commercial and profitable farming.

The government: Should avail political, institutional and infrastructural support to enhance the agricultural environment for transforming traditional farming practices into more profitable agricultural among smallholder farmers in Kigoma region.

• Basing on the study findings, inadequate political, institutional and infrastructural support in the area of agricultural development in particular in various areas of Kigoma including the study districts, the government through her instrumental actors including the Ministry of Agriculture is urged to enhance the agricultural environment through availing more political, institutional and infrastructural support including supporting policies, subsidies and other related interventions. This will be useful in the course of enhancing agricultural production and productivity among smallholder farmers in Tanzania.

Acknowledgement

This study has been accomplished by dedicated efforts of the smallholder farmers of Kigoma region in Tanzania. Their support, courage and cooperation rendered to me in the course of realizing this study were incredible. Smallholder farmers will always remain my teachers and distinguished experts in generating agriculture knowledge. Indeed, I appreciate every kind of support I got from all actors and leaders in the study area in the course undertaking this study.

Conflict of Interest

No conflict of interest.

References

- FAO (2015) The State of Food Insecurity in the World 2015. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. Rome.

- Dixon J, A Gulliver with D Gibbon (2003) Farming systems and poverty: improving farmers’ livelihoods in a changing world. Malcolm Hall, ed. Rome, FAO and Washington DC, World Bank.

- Vermeulen SJ, Aggarwal PK, Ainslie A, Angelone C, Campbell BM (2012) Options for support to agriculture and food security under climate change. Environ. Sci Policy 15:136–44.

- FAO (2014) Understanding smallholder farmer attitudes to commercialization – The case of maize in Kenya. Rome.

- World Vision (2013) Market assessment for wekeza project. A study report to assess opportunities to address the problem of child labour in Kigoma and Tanga regions.

- Niang I, OC Ruppel, MA Abdrabo, A Essel, C Lennard, J Padgham (2014) Climate change: impacts, adaptation, and vulnerability: Regional Aspects. Contribution of Working Group II to the 5th Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Cambridge Univ. Press, Cambridge, United Kingdom and New York, NY.

- Wheeler Tim, Joachim von Braun (2013) Climate Change Impacts on Global Food Security. Science 341(6145): 508–13.

- Lashgarara F, Hosseini JF, Mirdamadi M (2008) Information Technology and Rural Marketing. Case Study in Iran.

- Sharma VP (2006) Cyber Extension: Information and Communication Technology (ICT) Application for Effective Agricultural Extension Services– Challenges, Opportunities, Issues and Strategies. In: Enhancement of Extension Systems in Agriculture. Published by the Asian Productivity Organization, Tokyo.

- Dina U (2006) Linking Small Farmers to the Market. Agriculture Economist for the South Asia Region. World Bank.

- Rweyemamu D (2003) Reforms in the Agricultural Sector: The Tanzanian Experience. Global Development Network.

- United Republic of Tanzania (URT) (2010a) National Strategy for Growth and Reduction of Poverty (NSGRP) II.’ Ministry of Finance and Economic Affairs. Dar es Salaam.

- World Bank (2016) World Development Indicators.

- Mutabazi K, Wiggins S, Mdoe N (2010) Informal Institutions and Agriculture in Africa. Cell phones, Transaction Costs & Agricultural Supply Chains: The Case of Onions in central Tanzania. Manchester & Morogoro: IPPG Discussion Paper 49.

- Natai S (2016) National Climate Smart Agriculture Programme (2015-2025). Ministry of Agriculture Food Security and Cooperatives - Tanzania. GACSA National Policy dialogue, 29th March 2016, ESRF Conference Hall, Dar es Salaam, Tanzania.

- United Republic of Tanzania (URT) (2001) Agricultural Sector Development Strategy (ASDS). Ministry of Agriculture, Food Security and Cooperatives, Dar-es Salaam.

- World Bank (2009) Awakening Africa’s Sleeping Giant: Commercial Agriculture in the Guinea Savannah and Beyond, Washington DC.

- Bucheyeki TL, Mmbaga TE (2013) On-Farm Evaluation of Beans Varieties for Adaptation and Adoption in Kigoma Region in Tanzania. ISRN Agronomy; Volume 2013.

- United Republic of Tanzania URT (2010b) The Economic Survey 2009. Ministry of Finance and Economic Affairs. Dar es Salaam.

- Revolutionary Government of Zanzibar (RGoZ) (2010) The Zanzibar Strategy for Growth and Reduction of Poverty: 2010-2015 (ZSGRPII), MKUZA II, SMZ, Zanzibar. 197pp.

- Rwehumbiza FBR (2014) A Comprehensive Scoping and Assessment Study of Climate Smart Agriculture (CSA) Policies in Tanzania. The Food, Agriculture and Natural Resources Policy Analysis Network (FANRPAN).

- Lewis L, Onsongo M, Njapau H, Schurz-Rogers H, Luber G (2005) Aflatoxin contamination of commercial maize products during an outbreak of acute aflatoxicosis in Eastern and Central Kenya. Environ Health Perspect 113: 1763–67.

- Bryman A, Bell E (2011) Business Research Methods. (3rd ed.), Oxford University Press, New York, 765pp.

- Cooper D, Schindler P (2003) Business research methods, (8th ed.). New York: McGraw- Hill.

- Kothari CR (2004) Research Methodology (method and technique), (2nd ed,). New Delhi: K.K Gupta for New Age International (P) Ltd.

- Wilson G, Keam LM (2015) Gender and Social Inclusion in Climate-Smart Agriculture Programme (VUNA). UK Department for International Development (DFID).

-

Chami Avit A. Potentials of Commercialization of Smallholder Farming in Kigoma Region, Tanzania: Gross Profit Margin Analysis of selected Crops in Selected Districts, Kigoma Region. World J Agri & Soil Sci. 5(4): 2020. WJASS.MS.ID.000620.

-

Commercialization, Smallholder Farming, Gross-Profit-Margin-Analysis

-

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.