Research Article

Research Article

Effects of PGP Bacteria on Holding Water at Pot Scale

Mustafa Elfahl1, Sara Borin3, Francesca Mapelli3, Valentina Riva3, and Giovanna Dragonetti2*

1Department of Water Relations and Field Irrigation, Institute of Agricultural and Biological, National Research Centre, Giza, Egypt

2Mediterranean Agronomic Institute of Bari, IAMB, Bari, Italy

3Department of Agricultural and Environmental Sciences – Production, Landscape, Agroenergy, Università degli Studi di Milano, Milan, Italy

Corresponding AuthorGiovanna Dragonetti, Mediterranean Agronomic Institute of Bari, IAMB, Bari, Italy.

Received Date:September 05, 2024; Published Date:March 17, 2025

Abstract

Inoculating plants with selected beneficial bacteria can significantly enhance agricultural sustainability, providing vital solutions for regions facing drought conditions. In this study, a greenhouse experiment was conducted; wherein thirty potted tomato plantlets were inoculated with five Plant Growth-Promoting Bacteria (PGPB) strains: Micrococcus yunnanensis M1, Bacillus simplex RP26, Pseudomonas stutzeri SR7-77, Arthrobacter nitroguajacolicus 2-50, and Arthrobacter aurescens 2-T30, —previously isolated from the endosphere or rhizosphere of drought-adapted plants. Ten plants per strain were subjected to three different watering regimes: full irrigation (100%) matching the plant’s water requirement (PWR), moderate (75% PWR) and severe (50% PWR) irrigation. Soil moisture content was monitored using Time Domain Reflectometry (TDR) to assess the impact of bacterial inoculation on soil water storage and its influence on plant growth, as adequate moisture is necessary for nutrient uptake and photosynthesis. Results indicated that all inoculated strains improved plant performance, particularly under water stress conditions induced by reduced irrigation. Among the strains, Pseudomonas stutzeri SR7-77 demonstrated a significantly positive impact on soil water holding at pot scale, even under full irrigation, largely observed during the active growth stage. These results suggest that selected PGPB strains can enhance soil water availability and plant resilience, providing a viable strategy for improving tomato production in drought-affected regions.

Keywords:Plant Growth Promoting Bacteria (PGPB); Soil water fluxes; Time Domain Reflectometry (TDR); Greenhouse experiment; Air temperature

A Perspective

Water resources management is one of the most pressing environmental issues where water supply is limited worldwide [1]. Due to the water scarcity problems, water resources management in many arid and semiarid regions is facing a big challenge [2], especially because of the competition between industry, agriculture, municipal and energy utilization of water resources. In essence, at the global scale level, 80% - 90% of all the water is consumed in agriculture, which will increase by 60% during the first half of this century in order to meet the increasing demand for food [3]. Yet, considering the expected exacerbation of water scarcity due to climate change, Mediterranean African Countries (MACs) will face particularly severe challenges. This situation is further compounded by the projection that water demand will increase by 47% from 2015 to 2035 [4].

With projections indicating the need to increase agricultural production and water use, it is advocated to focus efforts on ensuring water productivity in irrigated agriculture [5]. Thus, it becomes urgent to identify and adopt effective irrigation management strategies that can save significant quantities of water in the agricultural sector, compared to other sectors.

Traditionally, agricultural research has focused primarily on maximizing total production. However, in recent years, attention has shifted to the limiting factors in production systems, notably the decreasing availability of water resources [6], yet the portion of fresh water currently available for agriculture (72%) is decreasing [7]. Hence, sustainable methods to increase crop water productivity are gaining importance in arid and semiarid regions [8]. To achieve the highest benefits from gradually decreasing irrigation water resources, it is crucial to maximize yield per unit of water.

In times of severe water shortages or drought conditions, therefore, irrigation scheduling should be meticulously designed to meet crop needs precisely and prevent water loss to percolation below the root zone. This implies defining irrigation plans based on physical processes that account for water dynamics. Alternatively, selecting irrigation schedules that prioritize water productivity, incorporate soil water measurements, or utilize various combinations of these methods is essential for optimizing water use.

Methods using soil water content measurements, such as simple water balance approaches that estimate evapotranspiration [9-13] and root water uptake [14-16] by calculating the difference in soil water storage between two different observation times, can result in increased water use efficiency, significant water conservation, and minimized deep percolation fluxes. Thus, soil plays a very important role in irrigation water management. In this regard, when water is applied to the soil surface, either as irrigation or as rainfall, a part or all of this water enters into the soil matrix. While the eventual remaining water flows over the soil surface as runoff, it can also contribute to infiltration through the soil at a later stage.

Additionally, largely used innovative method to save agricultural water is conventional Deficit Irrigation (DI). It is a water-saving strategy under which crops are exposed to a certain level of water stress either during a particular developmental stage or throughout the whole growing season [17]. But, under drought conditions, relying solely on these techniques that compensate for evapotranspiration losses might not suffice to overcome agricultural water shortages. On the other hand, an additional alternative to cope with water scarcity is to integrate a proper irrigation schedule with these strategies as well. Within this context, effective irrigation water management could be enhanced by combining “beneficial bacteria”, which have the potential to mitigate drought stress conditions, improving crop resilience and productivity with a soil water content monitoring, ensuring sustainable water usage and healthier crops.

With respect to innovative technology, the use of various bacterial species in irrigated agriculture has been confirmed [18,19]. Mostly are associated with the plant rhizosphere and are routinely referred to as Plant Growth Promoting Bacteria (PGPB). PGPB are originally defined as root-colonizing bacteria that cause either plant growth promotion or biological control of plant diseases. PGPB can be applied in agricultural production because can stimulate plant growth, increase yield, reduce pathogen infection, as well as reduce biotic or abiotic plant stress, without conferring pathogenicity [20-22]. With the inoculation of plant growth-promoting (PGP) bacteria, plants experience significantly enhanced growth and yield, along with increased resistance to water stress and salinity. When combined notably with non-conventional resources like treated wastewater, their synergy boosts overall productivity. Therefore, integrating this practice with a proper irrigation plan not only improves water efficiency but also enables the cultivation of crops in drought-prone areas.

Commonly, bacterial strains with PGP activity are isolated, characterized, and tested with specific aims to: (i) increase plant growth under conditions of water stress, sustaining plant productivity even with limited irrigation, and (ii) increase tolerance to the high salinity levels, which is one of the features characterizing treated wastewater. Moreover, PGPB inoculation is a promising practice to ameliorate the soil properties and soil water holding capacity, having observed that the bacteria make available water at severe water stress conditions facilitating root water uptake even though prolonged drought conditions. To this regard, Dragonetti, et al. [23] observed that inoculating bacteria stimulated root development, making water available even at extremely waterlimiting conditions, due to the PGPBs’ potential to modify pore size distribution under water deficit conditions.

In consideration of the increasing prevalence of water scarcity, tomato (Lycopersicon esculentum Mill) is considered one of the crops that are generally known to be moderately sensitive to water deficit. Moreover, no horticultural crop has been instrumental as tomatoes in numerous breakthroughs. Their rich potential for exploration has led to advancements in disease resistance, extended shelf life enhanced nutritional content and improved flavor, contributing pivotally to advancements in agricultural science. Tomatoes are indeed versatile horticultural plants, enjoyed as both vegetables and fruits [25], commercially grown in 159 countries. In the Mediterranean, the leading producers are Turkey, Egypt, Italy, Spain, Tunisia, Portugal, and Morocco [26].

Based on these premises, the effects of inoculating beneficial bacteria on potted tomato plants under different watering regimes were tested by evaluating their influence on soil water storage and water fluxes. Specifically, the study assessed the effects of five bacterial strains (Micrococcus yunnanensis M1, Bacillus simplex RP26, Pseudomonas stutzeri SR7-77, Arthrobacter nitroguajacolicus 2-50, and Arthrobacter aurescens 2-T30) on plants after (100% of plant water requirement- PWR ), and two deficit irrigation levels (75% and 50% PWR). Yet, to evaluate the impact of bacterial inoculation on soil water content, measurements are taken and compared to un-inoculated control plants to determine how bacterial inoculation affects water availability and usage within the soil, ultimately enhancing plant growth and water efficiency.

Materials and Methods

Experimental design

The experiment was conducted at the Mediterranean Agronomic Institute of Bari (IAMB) located in Apulia region with latitude of 41°03’ N, longitude of 16°51’ E and altitude of 72 m above sea level. The trial was carried out from 24 January to 19 July 2017 in a semicontrolled greenhouse equipped with fiberglass walls and a lateral and top system of automatic aeration.

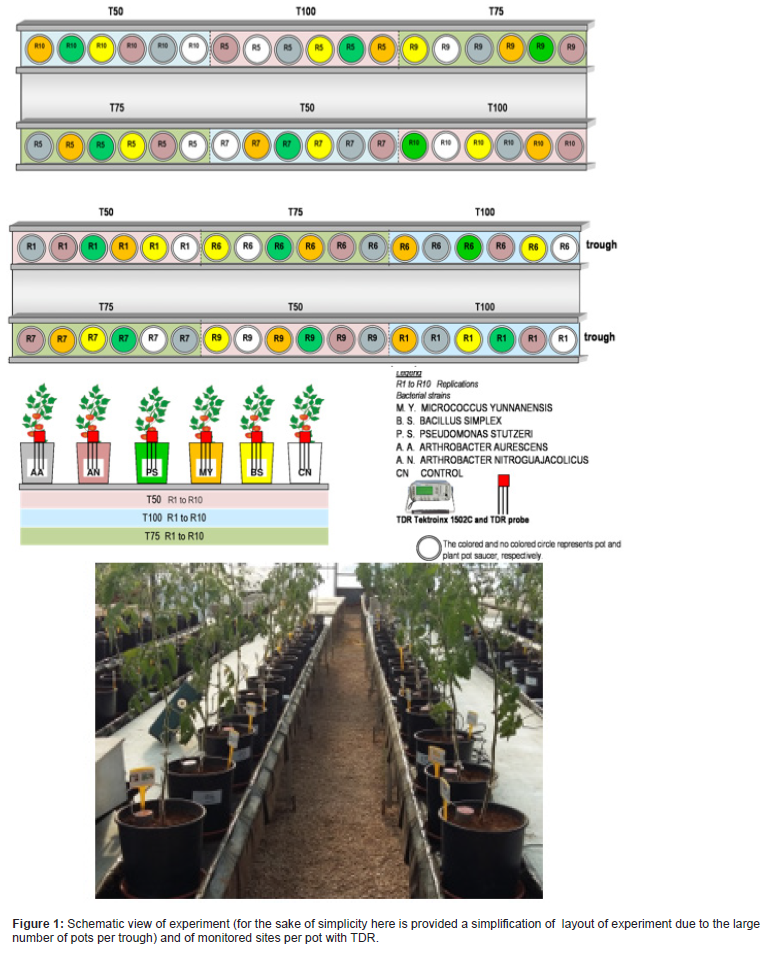

The experiment was laid out as split-pots based on randomized design (Figure 1). Three levels of water were induced: full irrigation and two deficit irrigation, applied based on plant water requirement, so named: T50 (50%); T75 (75%); T100 (100%), respectively; and five types of bacteria species, and a control (without bacterial). Overall, 180 tomato pots were performed for three water regimes with six treatments and ten replications.

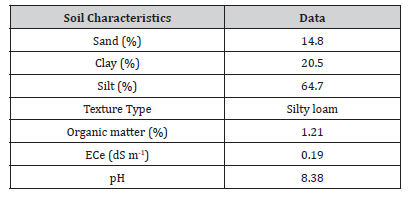

Preliminary soil and water characteristics were determined before setting up the experiment, establishing a baseline condition to assess the effects of bacterial inoculation at varying irrigation levels on soil water storage and water fluxes in potted tomato plants. The soil textural class was obtained according to the USDA classification (USDA, Soil Taxonomy). The electrical conductivity of the extract soil solution (ECe) was lower than 1 dSm-1 and the pH was under 8.5, as shown in (Table 1).

Table 1:Soil characteristics.

The tomato test was performed in PVC pots, type “BAMAPLAST” with a diameter of 24 cm and height of 24 cm and soil volume of roughly 9.5 L and spit on 10 benches. The benches were made from a galvanized metal in order to prevent corrosion and fungal growth. They were 0.55 m height from the ground and each one had 11 m length and 1.4 m width. They were arranged in a way to ensure a slope of 1 %, thus allowing and collecting the drainage fluxes. The benches served as support for the pots, and separated 0.6 m apart, which support two troughs, allowing a good access to do different plant management practices (tutoring, harvesting, etc.). The troughs are aluminum canals with a rectangular section, 9 m length, 29 cm width and 6 cm depth, and covered with a 0.15 mm thick black plastic film. Each bench is made up of two troughs. Each trough was equipped with 18 pots. Pots are distinguished per six treatment (M.Y., B.S., P.S., A.N., A.A., and CN) and three water regimes (T100, T75 and T50). Soil parameters were monitored for 90 pots during the experimental trial.

Irrigation scheduling

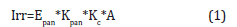

Irrigation was managed by watering the pots every two days, and the soil water balance method was used to compensate for the water lost through evapotranspiration. While, Evapotraspiration fluxes were monitored using both evaporation pan Class A, and soil water balance method. In detail, irrigation water potential was calculated based on Class A pan evaporation as follows [27]:

where A is pot area (m2), Epan cumulative evaporation, Kpan and Kc are pan and crop coefficients, respectively. In this study, Kc coefficients were set for different stages. Kc =0.40 (transplanting), 0.75 (beginning flowering), 1.06 (flowering – beginning harvesting), 1.25 (harvesting) and 1.0 (late season) (Valdés-Gómez et al. 2009), while Kpan coefficient was setting [26].

The purpose of the irrigation scheduling was to supply water accounting for only losses due to evapotranspiration, as no drainage occurred. Additionally, since the Evaporimeter Class A estimates water losses primarily based on surrounding climatic conditions without considering soils interactions, this computation was also compared using a water balance approach. This accounts more accurately for the water exchanges among soil pot, plant and greenhouse environmental.

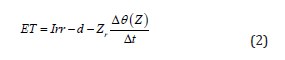

Weekly, the water balance was thus used to estimate actual evapotranspiration [10-13] and root water uptake [14-16] by calculating the difference in soil water storage between two observation times. Using Naranjo et al. [11] single-layer method to derive evapotranspiration, water fluxes were obtained by analyzing time series of irrigation and changes in soil water content before and after irrigation, where water contents were estimated using TDR measurements at soil depth.

The equation is:

where zr is the active rooting depth and is taken equal to the measurement depth of volumetric soil water content, θ, and Δt indicates the length between two irrigation events, Irr is the irrigation volume, d is the flux out of the soil layer during the same time step and ET is evapotranspiration.

When irrigation occurs, both infiltration and soil water fluxes take place. By controlling and observing that percolation fluxes (d) were negligible [16], Eq. 2 simplifies to Eq. 3:

where is soil water storage estimated according to TDR readings.

Thus, at each irrigation event, the evpotranspiration estimated by the Class A Pan was compared with that obtained using water balance to assess the irrigation scheduling performance. As a ratio between evapotraspiration estimated by Class A Pan and water balance, a correction factor was calculated to determine the percentage difference between the two methods. However, it was observed that the evapotraspiration based on the water balance, which mainly accounted for water storage in its calculation, was more accurate and resulted in 8% water saving.

Soil water content monitoring

The evolution of soil water content in space and time was monitored during the whole tomato growth season. The measurements were recorded by using two methods: Time Domain Reflectometry (TDR) and thermo-gravimetric technique.

Since TDR probes were only installed for three replications (Figure 1), while gravimetric water content was available for all pots, measured weekly before and after irrigation, consequently at the end of the experiment, disturbed soil samples were collected from those pots with TDR probes installed. This enabled the determination of the relationship between gravimetric water content—converted to volumetric via bulk density—and volumetric water content estimated by TDR, then used to retrieve the volumetric water content for the remaining pots where TDR readings not available.

Time Domain Reflectometer (TDR) technique

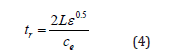

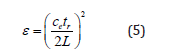

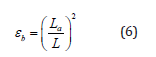

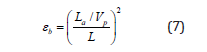

TDR is an indirect method to determine the volumetric soil water content. It measures the relative dielectric constant of a soil sample from which the soil water content can be inferred. The relative dielectric permittivity (ε) is determined by a TDR reflectometer. The travel time (t) of the wave, from the beginning to the end of the probe, is measured using a sampling oscilloscope and calculated as:

where tr is the round-trip time (s); L is the TDR probe length (m); ε is the dielectric constant being the material a composite mixture such a soil, it refers it as bulk dielectric permittivity (εb). and ce is the velocity of electromagnetic waves in free space (m s-1) (3*108). Rearranging Eq. (4) with respect to ε gives:

In a commercial TDR cable tester, the term (ce tr /2) in Eq. (5) is reduced to an apparent probe length (La) displayed on the cable tester (Baker and Allmaras, 1990).

where La is determined as a distance between reflections at the beginning and the end of the probe. The ratio of the velocity of propagation (Vp) in a coaxial cable to that in free space should be selected for measurement. For any selected Vp values, La should be corrected as in free space because a probe in soil has a different Vp from the coaxial cable. Thus, Eq. (6) is rewritten as:

The apparent distance La between the initial and final reflections can be determined from waves reflected back from a probe. The reflection coefficient (ρ) is defined as a ratio of the reflected amplitude of the signal from a cable to the signal amplitude applied to the cable. If there is an open circuit in the cable, nearly all the energy will be reflected back. The reflected amplitude will be equal to the incident amplitude and ρ = +1. If there is a short circuit, nearly all the energy will be delivered back to the cable tester through the ground. The polarity of the reflected pulse will be opposite of the incident pulse and ρ = -1. Therefore, the reflection coefficient for soil and weakly conducting solutions is usually between -1 and +1.

Equation (7) gives an apparent dielectric constant of soil using waves collected with a TDR cable tester. Because the dielectric constant of water is much larger than other soil constituents, determining water content by measuring a bulk dielectric constant of moist soil is quite reasonable.

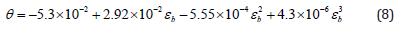

Volumetric water content θV (cm3 cm-3) is then calculated using a calibration curve empirically determined by Topp (1980) as:

where εb is the apparent dielectric permittivity measured by TDR.

Results and Discussion

Comparison TDR and thermo-gravimetric method to estimate soil volumetric water content

The gravimetric soil water content (θg) was determined by weight as the ratio of the weight of water to the dry weight of the soil pot, this latter obtained by drying the potted soil to constant weight and obtained at last campaign (19 July 2017). The gravimetric water content θg was converted into volumetric through bulk density, ρb, which is 1gcm-3.

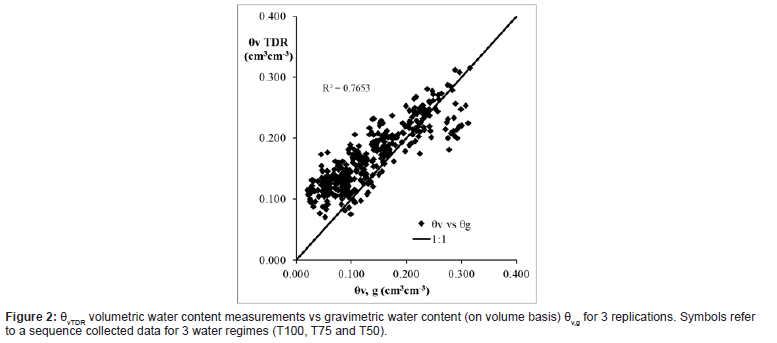

The calculated gravimetric moisture content converted in volumetric were compared against the volumetric soil water content acquired by TDR [28], as shown in the Figure 2.

For 3 replications and 3 water regimes, a relation between volumetric θv and gravimetric θv g soil water content data (on volume basis) was obtained through a linear regression.

Figure 2 illustrates a correspondence between gravimetric and TDR measurements, aligning along the 1:1 line. The correlation coefficient of 0.765 demonstrates that the TDR readings are accurate and consistent with those measured through the direct method.

Response to beneficial bacteria under optimal and limited irrigation

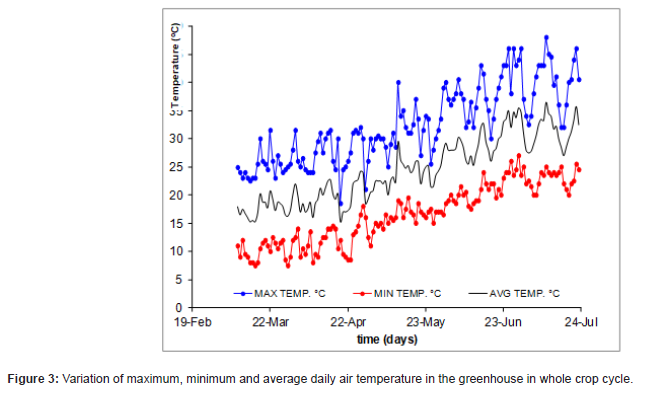

Before exploring the effects of PGPB on the soil water content distribution, it is paramount to assess the temperature behavior recorded in the greenhouse during the trial.

The evolution of the minimum, maximum and mean greenhouse temperature during the crop cycle (9 of March to 15 of July) is shown in Figure 3. Here is pretty evident that the internal mean temperature increased progressively with crop cycle from a value of 16 °C in the first week to a value of 31 °C in the week of 20 May, the mean temperature during the whole cycle was 24 °C. Concerning the maximum temperature, it was fluctuation between 25 °C during the first week and 44 °C on the last week of the crop cycle. The minimum temperature ranged between 8 °C on the first week and 20 °C on the last week. General optimal temperatures for tomato range between 21-28°C in daytime and 15 to 20°C at night [29]. Here, the recorded temperature’s values were relatively higher than the plant optimal range, especially during the middle of season until the end of the cycle, conferring an additional environmental stress to the plants beyond deficit irrigation, where on the contrary the PGPBs have allowed to cope this condition and allowing even to increase the water hold in the soil capacity making more water available to the tomato plant.

The effect of the three irrigation regimes (T100, T75 and T50) combined with five stains of beneficial bacteria on the tomato growth was investigated on soil parameters, especially regarding soil water fluxes from 22 March to 15 July. All soil water content data measured by TDR were averaged for three replications per irrigation regime.

All treatments are referred as follows: Micrococcus yunnanensis M1; Bacillus simplex RP26; Pseudomonas stutzeri SR7-77; Arthrobacter aurescens 2-T30; Arthrobacter nitroguajacolicus 2-50 and recalled as to: MY, BS, PS, AA and AN, respectively and not inoculated plants CN.

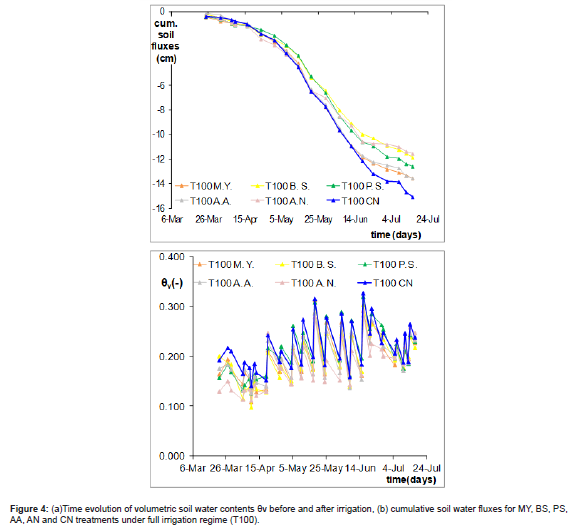

The time evolution of the volumetric soil water contents (θv) measured weekly by TDR in case of full irrigation (T100) from 22nd March to 15th July is depicted in Figure 4a. The variation is due to the water content changes before and after each irrigation. The changes of soil water content, Δθ, for each treatment (inoculated and non- inoculated test) were obtained as difference between before and after irrigation reading by TDR method (as mentioned in materials and methods) and integrated overtime as shown in the figure 4b. By controlling and observing that drainage fluxes did not occur during the experiment, it may be assumed that the estimated soil water fluxes accurately represent evapotranspiration rates.

It may be observed that the evolution of water contents tends to be similar after irrigation under all the five and not-inoculated treatments, while it decreases in the case of bacterized treatments before irrigation.It is worth noting two different behaviours (Figure 4b). One side, BS, PS and AN under full irrigation show a similar trend of soil water fluxes and always lower than control CN, another MY and AA demonstrated a similar behaviour to CN. Although irrigation volumes were delivered similarly to all pots of the same irrigation regime, the difference between each other can be due to different water uptake activity also induced by the action of PGP Bacteria. To this regard, Ren, et al. [30] observed that some PGP bacteria had promoted good growth having colonized the rape rhizosphere and endosphere.

Additionally, it was observed that PS and BS negatively influenced soil water content distribution under full irrigation (T100) from May 3 (indicated by the full black line) to the end of the season. This variation may be attributed to water stress conditions in the greenhouse during that period due to high temperatures, where PGPB played a relevant role in the other pots. In fact, AA and MY positively influenced tomato growth throughout the season compared to the other bacteria.

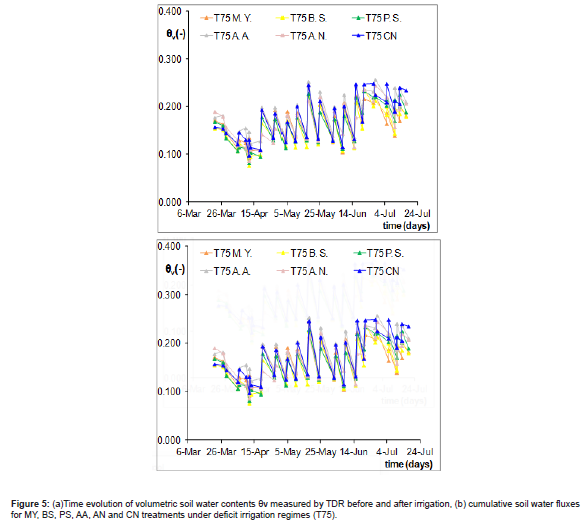

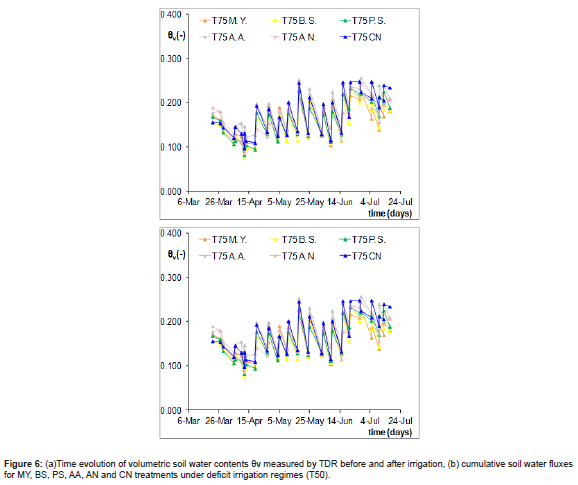

Figure 5a depicts the time evolution of volumetric soil water content θv refer to five and control treatments in whole tomato season under deficit irrigation (T75). The blue line which represents the soil water content trend refer to control (CN) has a similar variation than bacterized treatment both before and after irrigation. To the contrary, figure 5b shows that cumulative soil water fluxes and observed that in the case of MY and BS strains vary similar compared to control. While PS has shown a comparable behavior to CN, MY and BS strains; up to 21 May, then PS reduced his effect. This mechanism may be due to more sensitivity to stress conditions recorded after 21 May in the greenhouse.

While figure 6a represents the time variation of volumetric soil water contents observed at 50% irrigation. In this case, the variation of soil water content θv values for control was higher than bacterized tests. By looking at Figure 5b, it may observe that cumulative soil water fluxes estimated for all bacteria treatments were higher than CN. In detail, under severe stress the estimated soil water fluxes show high values for all strains up to 21 May, while PS has a positive effect in whole season condition compared to both control and other strains. With this regard, a study evaluated the ability of Variovorax paradoxus RAA3, Pseudomonas palleroniana DPB16, Pseudomonas sp. UW4 strains to overcome drought stress obtaining an improving of wheat yields in irrigated and rainfed field experiments [31].

In the same experiment, but focused on the tomato response, the results showed that under severe irrigation deficit, four of the tested strains—Micrococcus yunnanensis M1, Bacillus simplex RP-26, Pseudomonas stutzeri SR7-77, and Paenarthrobacter nitroguajacolicus 2-50—positively enhanced the number of productive plants compared to the non-bacterized control. In essence, for two of these strains, Bacillus simplex RP-26 and Arthrobacter nitroguajacolicus 2-50, a significant improvement in available soil water was observed even under full irrigation conditions when compared to non-inoculated tomato plants. These results were further confirmed by observing the evolution of soil water content throughout the tomato season, demonstrating how the actual plant growth-promoting (PGP) ability of a bacterial inoculant on plant production is influenced according to the adopted irrigation schedule [32].

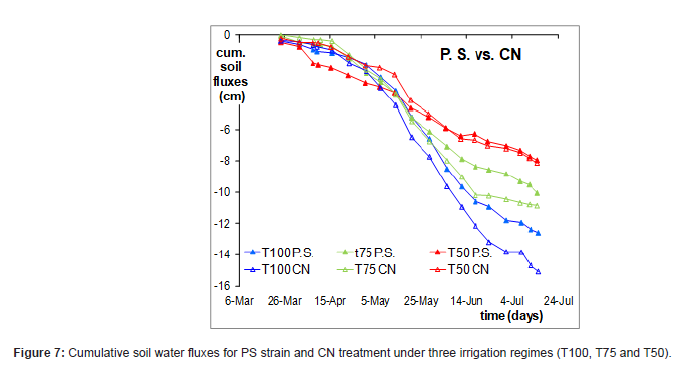

Regarding the behavior of all strains under full (T100) and limited irrigation (T75 and T50), it can be observed that PS was the only strain to show a significant effect compared to CN (Figure 7) in all water strategies. In detail, the red lines which represent the data refer to PS and CN under severe stress condition (T50) demonstrate a different response on soil water fluxes. Furthermore, an inverse behavior was observed for severe stress conditions (T50) compared to full and moderate stress up to the middle season. This effect can be explained by deeply investigating the mechanisms of bacteria in the root and plant area. In all likelihood the activity of PS under 50% of irrigation was full at beginning of the season period and up to 28 May, thus has improved the root uptake. After 28 May, the high temperature values have compromised the activity of the strain. While PS has not given a different response under full and moderate stress, T100 and T75 respectively.

According to this irrigation management, the soil water fluxes elicited varying responses in tomato growth, and it is likely that bacterial activity largely contributed to influencing water uptake. Overall, the effect of bacteria was confirmed by investigating the mechanisms of PGPB on tomato plants under different water regimes. Similarly, it was demonstrated that PGPB strains under different soil water contents—reproducing severe drought (30% of field capacity), moderate drought (50% of FC), and no drought (80% of FC) conditions—significantly promoted growth and root system development, but this effect was most notable in corn under moderate drought (50% of soil field capacity) [33], due to the different behavior of soil water fluxes.

Conclusion

The results of this study suggest that all bacterial species positively affected tomato plants, particularly under mild stress conditions, and have a great potential to increase soil water availability for tomato pots. The inoculated bacteria significantly influenced soil water fluxes, enabling the plants to better tolerate water stress conditions.

According to M. yunnanensis M1, this strain established a positive plant-bacteria relationship and improved water content at all irrigation regimes. Regarding Bacillus simplex (RP26), this strain established a positive plant-bacteria relationship and positively affected soil water fluxes under both drought and normal irrigation conditions. In contrast, Pseudomonas stutzeri (SR7-77) not only established a positive plant-bacteria relationship but also increased soil water storage during severe stress conditions. Yet, SR7-77 had a positive effect on soil water fluxes compared to the control under stress conditions. Arthrobacter Aurescens (2-T30) showed no significant effect on soil water storage, on the other hand Arthrobacter nitroguajacolicus (2-50) showed a positive effect on soil water fluxes under mild stress conditions.

These results indicate that selected PGP strains have the potential to significantly improve the response of tomato to drought. Specifically, Pseudomonas stutzeri SR7-77 was the only strain to positively affected tomato growth under limited irrigation when compared to non-inoculated treatments. This makes SR7-77 a particularly promising candidate for future research. Additionally, strains that potentially reduce drought-related fruit losses, such as Micrococcus yunnanensis M1 and Bacillus simplex RP26, also show considerable potential for further investigation.

Overall, all bacteria positively influence the water uptake by plants under severe stress conditions, though their activity is affected by both climate conditions and water strategies. Yet, the Time Domain Reflectometer (TDR) technique accurately monitors changes in soil water content in potting experiments and helps minimize downward water fluxes by considering soil characteristics in the irrigation plan.

Acknowledgement

The authors deeply appreciate the opportunity to contribute to the MADFORWATER project, which has given us the possibility to provide this research. MADFORWATER Project: Development and application of integrated technologies and management solutions for water treatment and efficient reuse in agriculture tailored to the needs of Mediterranean African Countries was supported by European Union’s Horizon 2020.

Conflict of Interest

No conflict of interest.

References

- Postel SL (1998) Water for food production: will there be enough in 2025?. BioScience 48(8): 629-637.

- Garcia X, Pargament D (2015) Reusing wastewater to cope with water scarcity: Economic, social and environmental considerations for decision-making. Resources, Conservation and Recycling 101: 154-166.

- Carmody E, Turral H (2023) Consumption-based water management. State of the art in Asia. Bangkok, FAO.

- Frascari D, Zanaroli G, Motaleb MA, Annen G, Belguith K, et al. (2018) Integrated technological and management solutions for wastewater treatment and efficient agricultural reuse in Egypt, Morocco, and Tunisia. Integrated environmental assessment and management 14(4): 447-462.

- Scheierling Susanne M Treguer, David O (2016) Enhancing Water Productivity in Irrigated Agriculture in the Face of Water Scarcity. Agricultural and Applied Economics Association (AAEA) 33(1): 1-10.

- Geerts S, Raes D (2009) Deficit irrigation as an on-farm strategy to maximize crop water productivity in dry areas. Agricultural Water Management 96(9): 1275-1284.

- Cai X, Rosegrant MW (2003) 10 World Water Productivity: Current Situation and Future Options. Water Productivity in Agriculture, 163.

- Debaeke P, Aboudrare A (2004) Adaptation of crop management to water-limited environments. European Journal of Agronomy 21(4): 433-446.

- Oweis T, Zhang H (1998) Water-use efficiency: index for optimising supplemental irrigation of wheat in water scarce areas. Zeitschrift f. Bewaesserungswirtschaft 33(2): 321-336.

- Kosugi Y, Katsuyama M (2007) Evapotranspiration over a Japanese cypress forest. II. Comparison of the eddy covariance and water budget methods. Journal of Hydrology 334(3): 305-311.

- Naranjo JB, Weiler M, Stahl K (2011) Sensitivity of a data-driven soil water balance model to estimate summer evapotranspiration along a forest chronosequence. Hydrology and Earth System Sciences 15(11): 3461.

- Schume H, Hager H, Jost G (2005) Water and energy exchange above a mixed European Beech–Norway Spruce forest canopy: a comparison of eddy covariance against soil water depletion measurement. Theoretical and applied climatology 81(1-2): 87-100.

- Wilson KB, Hanson PJ, Mulholland PJ, Baldocchi DD, Wullschleger SD (2001) A comparison of methods for determining forest evapotranspiration and its components: sap-flow, soil water budget, eddy covariance and catchment water balance. Agricultural and forest Meteorology 106(2): 153-168.

- Eugenio Coelho F, Or D (1996) A parametric model for two‐dimensional water uptake intensity by corn roots under drip irrigation. Soil Science Society of America Journal 60(4): 1039-1049.

- Green S, Clothier B (1995) Root water uptake by kiwifruit vines following partial wetting of the root zone. Plant and Soil 173(2): 317-328.

- Hupet F, Lambot S, Javaux M, Vanclooster M (2002) On the identification of macroscopic root water uptake parameters from soil water content observations. Water resources research 38(12).

- Pereira LS, Oweis T, Zairi A (2002) Irrigation management under water scarcity. Agricultural water management 57(3): 175-206.

- Babalola OO, Sanni AI, Odhiambo GD, Torto B (2007) Plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria do not pose any deleterious effect on cowpea and detectable amounts of ethylene are produced. World Journal of Microbiology and Biotechnology 23(6): 747-752.

- Zahir Z, Munir A, Asghar H, Shaharoona B, Arshad M (2008) Effectiveness of rhizobacteria containing ACC deaminase for growth promotion of peas (Pisum sativum) under drought conditions. J Microbiol Biotechnol 18(5): 958-963.

- Lugtenberg B, Kamilova F (2009) Plant-growth-promoting rhizobacteria. Annual review of microbiology 63: 541-556.

- Van Loon L, Bakker P (2005) Induced systemic resistance as a mechanism of disease suppression by rhizobacteria. In: (eds). PGPR: Biocontrol and biofertilization: Springer, pp. 39-66.

- Welbaum GE, Sturz AV, Dong Z, Nowak J (2004) Managing soil microorganisms to improve productivity of agro-ecosystems. Critical Reviews in Plant Sciences 23(2): 175-193.

- Dragonetti G, Cherradi S, Mapelli F, Riva V, Choukr-Allah R, et al. (2024) Inoculating plant growth-promoting bacteria-effects on soil hydraulic properties and tomato root development under water stress conditions. Agriculture and Food Sciences Research 11(1): 15-29.

- Dragonetti G, Khadra R (2023) Assessing Soil Dynamics and Improving Long-Standing Irrigation Management with Treated Wastewater: A Case Study on Citrus Trees in Palestine. Sustainability 15(18): 13518.

- Koesriharti, Ninuk H, Syamira (2012) Effect of Water Management on Yield of Tomato Plant(Lycpersicon esculentum Mill). J Agric Food Tech 2(1): 16-20

- FAOSTAT (2014) Global tomato production in 2012. Rome, FAO.

- Ertek A, Şensoy S, Gedik I, Küçükyumuk C (2006) Irrigation scheduling based on pan evaporation values for cucumber (Cucumissativus L.) grown under field conditions. Agricultural Water Management 81(1): 159-172.

- Topp GC, Davis JL, Annan AP (1980) Electromagnetic determination of soil water content: Measurements in coaxial transmission lines. Water resources research 16(3): 574-582.

- Reis Filgueira FA (2008) Novo manual de Olericultura: agrotecnologia moderna na produção e comercialização de hortaliças.

- Ren XM, Guo SJ, Tian W, Chen Y, Han H, et al. (2019) Effects of plant growth-promoting bacteria (PGPB) inoculation on the growth, antioxidant activity, Cu uptake, and bacterial community structure of rape (Brassica napus L.) grown in Cu-contaminated agricultural soil. Frontiers in microbiology 10: 1455.

- Chandra D, Srivastava R, Gupta VV, Franco CM, Paasricha N, et al. (2019) Field performance of bacterial inoculants to alleviate water stress effects in wheat (Triticum aestivum L.). Plant and soil 441: 261-281.

- Riva V, Mapelli F, Dragonetti G, Elfahl M, Vergani L, et al. (2021) Bacterial inoculants mitigating water scarcity in tomato: the importance of long-term in vivo experiments. Frontiers in Microbiology 12: 675552.

- Araújo VLVP, Fracetto GGM, Silva AMM, de Araujo Pereira AP, Freitas CCG, et al. (2023) Potential of growth-promoting bacteria in maize (Zea mays L.) varies according to soil moisture. Microbiological Research 271: 127352.

-

Mustafa Elfahl, Sara Borin, Francesca Mapelli, Valentina Riva, and Giovanna Dragonetti*. Effects of PGP Bacteria on Holding Water at Pot Scale. World J Agri & Soil Sci. 9(3): 2025. WJASS.MS.ID.000714.

-

Plant Growth Promoting Bacteria (PGPB), Soil water fluxes, Time Domain Reflectometry (TDR), Greenhouse experiment, Air temperature

-

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.