Research Article

Research Article

WTP for Luxury EVs and their Attributes: A BayesianApproach to Highlight the Ecology Effect on DM

Houssam Jedidi* and Oliver Heil

1Department of Marketing, Johannes Gutenberg University of Mainz, Germany

2Cahir of Marketing at Gutenberg University of Mainz, Germany

Houssam Jedidi, Johannes Gutenberg University ofMainz, Marketing Department (Prof. Dr. Oliver P. Heil (PhD.)), Jackob-WelderWeg. 9, Mainz, Rheinland-Pfalz, Germany.

Received Date: July 24, 2019; Published Date: August 05, 2019

Synopsis

Environmental friendliness, ecology and sustainability are all concepts challenging today’s’ industry, especially the luxury market. This paperinvestigates the WTP for luxury electric vehicles and their attributes within the favorite brand. We therefore highlight the ecology effect on Decisionmaking (loyalty vs. churning). The results show high preferences for ecology (reduction of Co2 emission) as well as a high loyalty level. Unlikeprevious investigations, we found out that prosperous clients are not accepting lower ranges and longer charging times, even if they possess multiplevehicles. Moreover, they are willing to pay up to 10% more for environmental friendly cars from favorite brand (assumption: quality doesn’t succumbstatus-quo). Serving these clients with the right product, allow luxury car manufacturers to charge significantly higher prices and therefore toincrease profit and market share. Ignoring Ecology in the luxury car market results in customers’ churn.

Introduction

Sustainable and environmental friendly goods are daily gainingimportance and responsiveness. This has pushed companiesto acclimate their strategies into “green” policy. Even luxurymanufacturers are concerned since this can wholly destroy thebusiness and lead to customer churning. The risk is particularlyhigh in this segment due to its sensitivity and to the intricatecustomer requirements. For instance, researchers like Bendell andKleanthous, Kapferer and, Kapferer and Michaut [1-3] discussedthe implications of ignoring these norms, even if clients do notacclaim them openly. Unlike regular merchandises, prosperousbuyers have a deep liaison to their favorite brands due to the social,individual and functional benefits offered by luxury products [4-7].This ‘loyalty’ suggests a forgiveness buffer when these companiespartially lose their appeal or are temporary inferior relative to thecompetition. In other words, people are more likely to disregardsome attributes to, further consume their desirable trademarks.For example, one would ignore a missing Navigation system in aFerrari, but not in a Volkswagen. However, many uncertaintiesshould be revealed: to which extent customers would forgive theirfavorable brands when ignoring some aspects such as sustainabilityand ecology? What are the car attributes that enhance the WTP andtherefore loyalty?

This work evaluates the key aspects and motivations forluxury electric car buyers. In addition, it models the tolerancelevel for manufacturers. Many arguments legitimize the choice ofthe automobile segment. First, the market share within luxuries isabout 40% (€489 billion out of €1,2 trillion) in 2017 and shows acontinuous growth of 8% compared to 2016 (Bain and company,2017). Second, due to a low purchase frequency and to a highinvestment rate, people are more rational in their decisions. Inaddition, unlike fashion or jewelry, there is no discriminationeffect since both genders appreciate cars and use them. Fourth, acar symbolizes the best way to project prosperity such as Statusand prestige because they can only be consumed publicly. Finally,product experience (previous/ current) with a vehicle havegenerally a long cycle and shapes therefore the foundation forfuture choices [8,9]. For example, for someone who likes a specificcar and had a pleasing experience with it, the next purchase is morelikely to occur within the same brand. Even if the acquired productis the poorest in their evoked sets, it is expected that clients wouldignore some features and needs toward savor the brand. Typically,this is what all brands implicitly strive for because it strengthensthe true brand value through a forgiveness level.

This work evaluates the key aspects and motivations forluxury electric car buyers. In addition, it models the tolerancelevel for manufacturers. Many arguments legitimize the choice ofthe automobile segment. First, the market share within luxuries isabout 40% (€489 billion out of €1,2 trillion) in 2017 and shows acontinuous growth of 8% compared to 2016 (Bain and company,2017). Second, due to a low purchase frequency and to a highinvestment rate, people are more rational in their decisions. Inaddition, unlike fashion or jewelry, there is no discriminationeffect since both genders appreciate cars and use them. Fourth, acar symbolizes the best way to project prosperity such as Statusand prestige because they can only be consumed publicly. Finally,product experience (previous/ current) with a vehicle havegenerally a long cycle and shapes therefore the foundation forfuture choices [8,9]. For example, for someone who likes a specificcar and had a pleasing experience with it, the next purchase is morelikely to occur within the same brand. Even if the acquired productis the poorest in their evoked sets, it is expected that clients wouldignore some features and needs toward savor the brand. Typically,this is what all brands implicitly strive for because it strengthensthe true brand value through a forgiveness level.

The Effect of Brand and Customer Specificities on Loyalty

The academic literature on brand experience [10], brandattitude [11], brand involvement [12], brand attachment [13],brand personality [14] and brand image [15], Martínez Salinas& Pina Pérez, [16] studied the impact of firms’ dimensions onconsumers’ loyalty in different ways. They acknowledged theseassets as key aspects for a firm’s success. Furthermore, Aaker [17]and Grohmann [18] empathized the importance of self-congruencein affecting customer response to the brand. Generally, shoppersseek products that better symbolize them with particular traits toexpress their self-concept. Thomson et al. define it “as the cognitiveand affective understanding of who and what we are.” Besides, theconcept contains two different facets: the ‘actual-self’ (based onperceived reality of the self) and the ideal-self (based on dreams,goals and the striking self). According to Aaker [17] both wayscan lead to self-congruence through a brand that match one of thetwo traits. Once people find the variety that fulfil this necessity,they become more attached to it and, therefore loyal. However,most of the theories mentioned above flow in one direction (B2C).Consequently, it is necessary to reveal the darkness on consumer’sability, involvement and motivation to process information, andhis/her perception of the brand. Duesenberry [19] was the firstto introduce the idea of “habit formation” where he showed thatcurrent behavior is partially affected by past consumptions. Thiswas affirmed by Pollak [20]. Similarly, Lancaster [21] pointed outthat people consume a specific product because of its inherentvalues and surplus. Hawkins and Hoch [22] for example, observedsubjects’ judgement under different involvement levels. The findingssuggest that familiarity is a mediator for the truth effect. Meaning,when exposed to a familiar product, a so-called “ring the bell”reaction occurs and people are more likely to trust the information.Consequently, luxury car producers should make use of thisfinding (familiarity & market share) to introduce sustainable andenvironmental friendly goods. In the same context, Malär, Krohmer,Hoyer and Nyffenegger [23] presented a conceptual frameworkthat illustrates the relationship between self-congruence andemotional brand attachment. The model announces self-esteem,public self-consciousness and product involvement as mediators.In other words, customer’ characteristics and his/her involvementdetermine his/her relation to the brand. They are more related tothe brands that better reflect and confirm who they are rather thanto those that promise helping them achieving the ideal-self. Highendmanufacturers are then expected to identify new tendenciessuch as ecology and apply the right strategies to serve the newclientele. Such approach is decisive for both loyalty and futuresuccess. Nonetheless, loyalty is a relative concept since clients arealways seeking to maximize their utility (material & immaterial)through acquisition or consumption [24-26]. They might turn thewheel and choose completely different goods that better fit theircurrent needs. In general, people think they make decisions basedon trivial traits such as product attributes and monetary values. Infact, a real complex computation is behind. They, unconsciously,develop an approach based on both product related experience(emotional outcome from previous purchases) and expertise(ability to perform product related tasks successfully) to facilitatethe decision-making process.

To help marketers with “a useful foundation for research onconsumer behavior”, Alba and Hutchinson [27] introduced fivedimensions of consumer expertise (cognitive effort, cognitivestructure, analysis, elaboration and memory). The first twodimensions mentioned above were shown to have a positivebenefit on the latter. The Authors identified a simple but a potenteffect of repetition on cognitive effort: Familiarity reducesboth the effort and the reaction time during decision-making(automaticity). The second dimension describes the weights ofthe facts for both novices and experts. For instance, this cognitivestructure correlate positively with familiarity. Practitioners shouldbe aware of this finding that mediates the loyalty philosophy andmake use of it. For instance, in case market leaders are up to date,customers would trust them more than others and their decisionwon’t include a complex computation (automaticity). Pham andJohar [28] confirmed this finding and proposed a model of sourceidentification. They described the hierarchical source monitoringwhen people fail to retrieve the information’s source. The resultsseem to be trivial and useless for practitioners, but it is crucial inreality. For instance, the usage of unique labels, features, logos andtools permits to associate the brand with a higher individualitydegree. Therefore, the retrieving procedure follows the easiest andshortest path within the suggested model. In other words, peopleare familiar with the brand and are more likely to prefer it amongall others. If people decide to leave their favorite brand, an alarmshould be triggered.

In another work, Maclnnis and Jaworski [29] studied theinformation processing from advertisements. The proposedintegrative attitude formation model differentiates betweenutilitarian and hedonic needs, which result in cognitive andemotional responses. Furthermore, it stresses the effect ofclients’ AMO (ability, motivation and opportunity to processbrand information). Likewise, the outcome is useful in practice.For example, the model can be divided into 3 main blocks (AMO,elements of brand processing and the evaluative level) whichmakes it useful as a diagnostic tool. In this case, it is easy for firms tolocate the deficit, if the choices and attitudes are inconsistent withthe input (needs and AMO-antecedents). All the suggested studiesempathized the importance of consumers’ ability, motivation andopportunity to process the brand information on their attitudestoward a company (loyalty). Understanding buyers’ preferences ingeneral and the consistency of the brand perception with the firm’sexpectations specifically is advantageous. Therefore, marketingresearchers and practitioners need the complete set of puzzles toderive a consistent judgment, since fitting this discrepancy permitsto achieve an additional powerful dimension.

Customer Churning

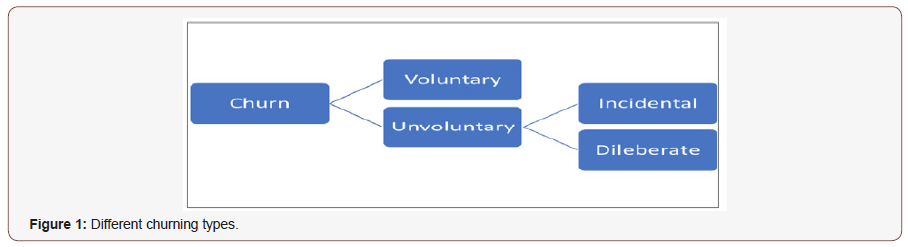

The churn philosophy can be classified into voluntary and nonvoluntary.The non-voluntary churners are easy to identify and todeal with [30]. These are customers who are pushed to abandon the brand for several explanations. For example, when firms revokea package or when clients are unable to pay an arrangement. it ismore critical when it emanates to voluntary churn. People makethen a conscious decision to cut with the brand. Afterwards,they switch to competitors. Analogous, this can be decomposedinto two categories: incidental and deliberate churn. The formerhappens when specific conditions avert the customer from hiscurrent consumption For instance, if he can’t afford the requiredfinancial means or moves to an unsuitable - geographical- area.The user is then more likely to terminate his rapport to the brand.The latter reveals high challenges for most companies. It occurswhen the clientele starts to empathize competitors’ products dueto their superiority in terms of technology, quality and economicalattributes. In this case, the task becomes tough through both,the intense competition and the variety of products and servicesthat faces the customer. Thus, Liu and Shih [31] related to theindispensability of new strategies that capture customer needs,progress the satisfaction level and so, retention. It has become acommonly acquaintance that company’s’ most important asset is thecustomer [32-33] Subsequently, businesses are opting customerorientedstrategies for sustaining their competitiveness andguarantee a stable profit. However, Keaveney (1995) accentuatedthe difficulty and the costs (advertising, promotional expensesetc.) of such processes in a saturated market where customersconstantly face a gigantic variety of products and services. To thisissue, Burez and Van den Poel [34] identified two approaches: thereactive and the proactive. Firms that adopt the reactive way aremore passive. They wait until clients ask to cut the relationship. Atthat point, they offer the customers higher incentives to hold them.Even if they succeed preserving their clients, the drawbacks likeexcessive costs, lower brand mercy and, purely incentive orientedrelationship will overwhelm. Contrarily, the proactive procedureoccurs when businesses primary focus on identifying risky clients(that are more likely to churn) and try to retain them. This kindof targeted strategy is advantageous. It allows to protect the corebusiness and to save market share. Additionally, proactive firms aregenerally more innovative and so, have a better image. Nonetheless,Van den Poel and Larivie’re [35] stressed the disadvantages of aninaccurate procedure. For example, companies would offer highincentives to clients who are not really churning.

Therefore, it is essential to be up to date, to identify the newtendencies, and to offer the clienteles the product and the qualitythey are looking for (or maybe a touch above). Moreover, it isrecommended that companies aim new customer generation [36-38]. Traditional methods of predicting churn risk are unprecisesince they only identify trends in data using pure mathematicalalgorithms. Additionally, businesses are often unable to identify if acustomer is more likely to switch to competitors until it is too late.The main reason for the usage such soft computing algorithms, istheir low cost. For the prediction of churn risks, companies usedto apply a pure demographic-based model. Wei and Chiu [39]criticized this approach since it creates an analysis which is basedon customers and ignore all other facets such as product attributes.Furthermore, due to restricted customer information, a puredemographic-based-prediction won’t be efficient. Additionally, theluxury academic literature on brand associations (attachment, love,involvement etc.) ignore such facets. They assume a continuousrelationship (untainted loyalty) once the customer appreciates abrand.

Empirical Study

The bayesian tradition: definition and properties

Powerful tools for estimating discrete choice models havebeen settled within the Bayesian technique. Unlike traditionalprocesses, these new methods can estimate model parameterswithout calculating the choice probabilities. Furthermore, they areefficient in deriving parameters on the individual level within anymodel and under random taste variation. For example, Albert andChib [40] have developed an exact Bayesian approach for modelingcategorical response data using the idea of data argumentation.McCulloch and Rossi [41] established new methods for conductinga finite sample, likelihood-based analysis of probit. The algorithmuses a variation of the Gibbs sampler and avoids a direct evaluationof the likelihood. Bayesian methods have numerous advantagescompared to frequentist. First, unlike probit and mixed logit wherethe MLE (Maximum Likelihood Estimator) can be associated withnumerical difficulties, Bayesian doesn’t require any maximization.Furthermore, traditional algorithms fail to converge in suchsituations and doesn’t guarantee that the maximum has beenreached. Even the choice of the starting values is still an issueTrain, [26]. Second, Bayesian procedures guarantee consistencyand efficiency with more relaxed assumptions. For instance, itsestimators are consistent for a fixed number of draws. If this amountrises at any rate with sample size, the coefficients are efficient.Cameron and Trivedi [42] stated out that Bayesian proceduresguarantee higher flexibility for the researcher since they deliver theentire posterior distribution of the parameters of interest. Meaningthe user can decide which moment/ quantile of the distributionto report based on decision theoretic criteria. Unlike frequentists,Bayesian methods are conditioned on data. The results are exactfinite and approach the normal distribution in large samples wherethe influence of priors disappears. Finally, Bayesian provides anatural way to select models [42, 26].

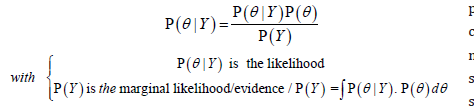

However, the Bayesian approach is linked to some costsespecially for researchers who are used to classical ways. Theyneed to be more familiar with various interrelated techniques.Afterwards, the learning curve gets steep. Also, the convergence isan issue, since Bayesian models use enough iterations to converge(takes a long time too). Unlike the convergence to a maximumby traditionalists. Bayesian scientists cannot therefore easilydetermine whether it is achieved or not. According to Train [26],McCulloch and Rossi [41] and, Albert and Chib [40], Bayesianare in many cases faster than classical approaches and providesatisfying pattern for inference and decision making. Undercertain assumptions, the estimators are asymptotically equivalentto the MLE and can therefore be interpreted in a classical way.The researcher has initially some ideas about the parameters θof his/her model. He/she collected data to improve or to update his/her beliefs that are represented by a probability distribution(P(θ)) over all possible values that θ can take. This is termedprior. He/she observes the choice of N independent decisionmakers Y={Y_1,Y_2,…Y_N}. Based on this sample information, thescientist updates his/her ideas about the value of θ. This is denotedas posterior distribution P(θ|Y) and depends on y since it onlyincorporates the information contained in the observed sample. Inconclusion, there is a definite relationship between the posteriorand the prior through the Bayes’ rule:

Specification of the prior

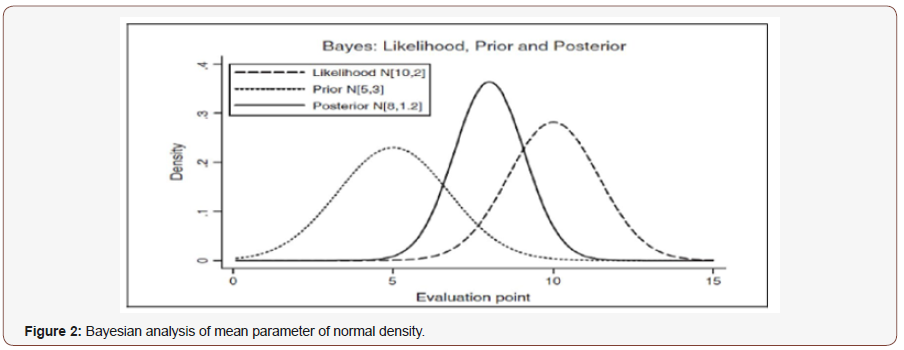

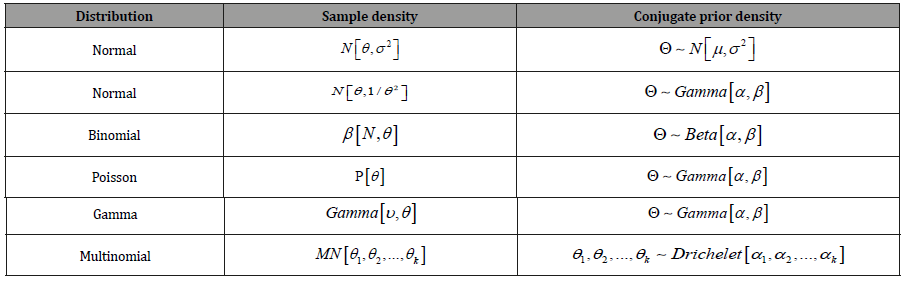

The researcher can choose between non- and informativepriors depending on the available data and his/her goal.Noninformative priors have minor impact on posteriors. It is aneffortless way since the choice of a uniform prior 𝜋(𝜃) = 𝑐 (∀ θ/c>0) places equal weights on all possible values of θ. However, incases where the parameters θ are unbounded, the density ∫𝜋(𝜃)𝑑𝜃 = ∞ is improper and implies an improper posterior. Also, the prior is invariant to reparameterization. Meaning, if it is unsuitablefor one parametrization, it will be unsuitable to all others. A wellknownuninformative prior is the Jefferys’ prior (Also known asvague, diffuse or flat) which has a large variance 𝜎2. It can serve as amethod of generating a prior when there are no obvious candidatepriors available. Conjugate priors (informative or diffuse) require aconvenient functional formula for the prior and result in a good andmethodically tractable illustration of the posterior under definitesample density of the data. Natural conjugate pair means that thesample density, prior and posterior, lie in the same class of densities(Figure 2). Table 1 summarizes the most used conjugate families(Figure 1&2) (Table 1).

Procedure

This is a nonequivalent quasi-experimental study and censusmethod is used due to the limitations of the statistical population.The students were divided into two groups of control group andexperimental group in this study. The experimental group wastaught using flipped classroom method and the control groupwas taught using the speech-based method. Experts in the fieldof general medicine were consulted about the class selection andthe teaching subject. When both groups were taught, the level ofparticipants’ learning was evaluated in the study using KirkpatrickEvaluation Model. The experimental group watched the electroniccontent of each session on a CD, studied the textbook and attendedthe class prepared. However, no content was available for thespeech-based teaching group and they attended the class as usual(Table 1).

Table 1:Most used conjugate families.

Markov chain monte carlo simulation

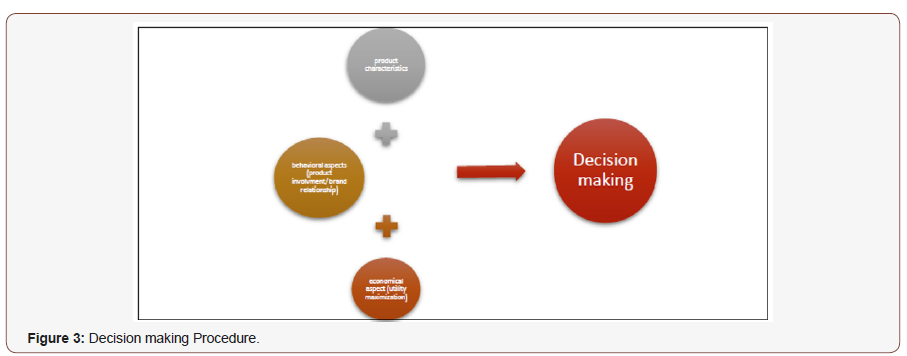

The researcher aims to get a large sample from the posteriordistribution since it provides desired information about boththe moment characteristics of the sample of estimates and otherrelevant measures. This task is more complicated if there is noclosed-form expression for posterior density. Using Monte CarloMarkov Chain method, the scientist run sequential draws thatharvest simulated values. Running long enough sequences is akey aspect here. Subsequently, the values converge to a stationarydistribution that coincides with the target posterior densityp(θ|Y). the Method named MCMC referring to simulation MonteCarlo and the sequence of Markov Chain that uses 2 approaches:Gibbs Sampler and Metropolis Hastings. In conclusion, productcharacteristics have a key influence on decision making. On the oneside, product involvement/ characteristics and brand relationshipbuild the fundament of the behavioral aspects especially, in the highendsegment where people are better informed, experienced andhave deeper liaison to their favorite manufacturers. On the otherside, as mentioned by the economic perspective, customers seekto maximize their relative utility through the choice of a specificgood among others. A juncture of both views yields the decisioneither to buy or not and which product. Again, this is primary forluxury houses since psychological, social, functional and financialdimensions play a deeper role in the decision making compared tomass producers.

Choice of attributes and data collection

As mentioned above, the car industry is a main componentfor the success and the accomplishment of the luxury market.For instance, an increase of round 11% was recorded between2016 and 2017 so that the business’ market share is about 41%(€489 billion out of €1,2 trillion) in 2017 Bain and company, [43].Additionally, the appearance of new tastes, namely ecology andsustainability has led to numerous challenges. Car manufacturershave the task to, first conserve their clients who are looking forthe fundamentals of high-end merchandises, and second serve thenew tastes and attract them. Numerous studies [44,45]) have beenconducted to elucidate the willingness to pay for electric vehicles.Based on the following car attributes: driving range, charging time,fuel cost saving, pollution reduction, and performance, respondentswere asked to choose between three alternatives, the vehicle theyare more likely to buy. as a result, people prefer functional featureslike higher driving range, fuel cost saving and faster charging time.The Co2 emission, which is the specificity of battery electric vehicles(BEV), was significant but not conclusive in the decision making.All studies were aiming to evaluate car attributes and were aboutmass products. However, prosperous buyers have a unique impulseand their relations to brands are much more robust. Subsequently,their choices and preferences are based on completely distinctaspects that should be investigated. Thus, luxury car producersobtain a better and wider view on the new market necessities.Unlike commodities, high-end products should display statusand some other social ans individual values through high quality,exclusivity, indulgence etc. [4,46,6,47,48]. Most prosperous buyersare therefore seeking expensive goods that keep them privilegedor at least guarantee a certain status level. Performance in termsof acceleration is an excellent quality and prestige indicator. Fastvehicles are gladly seen and appreciated. Subsequently, the ownernot only enjoys the driving experience, he/she also adores beinghonored and appreciated by others since cars can only be consumedpublicly.

• H1a: independent on their backgrounds (e.g. snobs,Veblenian etc.), all prosperous buyers show strongpreferences for high acceleration from favorite carmanufacturers.

The arousal theory builds the fundamental of the behavioralpsychology in understanding decision-makings. Besides, while thiswork deals with the WTP for luxury EVs, it is necessary to revealthe darkness on some aspects like customer need for novelty andhis/ her perception of new products like ecological luxury vehicles.According to academics like Garcia- Torres [49]and Johnson-Laird, Girotto and Legrenzi (2004) [50], and Legrenzi and Umita[51], the arousal level is positive and, strongly related to wellbeingand feelings. Subsequently, it determines peoples’ performances.Furthermore, the theory supports the idea that performancenecessitates a variety of stimuli (Hebb [52]; Berlyne, 1970 [53]).For instance, clients prefer a rich set of products with distinctivefeatures, so they have enough choice and their decision would bemore consistent. However, the authors recommend a moderatearousal level since its’ consequences follow a U- inverted curve:very low as well as very high stimulations won’t allow people toperform well. Likewise, this finding is primary for luxury carmanufacturers since producing non-familiar vehicles might havenegative consequences.

Berlyne [53,54] investigated the novelty effect on buyingdecision. He stated out that customer’ need for newness andoriginality affects the hedonistic degree of the stimuli. Meaning,people favor to get enough stimuli from outside to be well. Thisoverlaps with the fundaments of luxury such as high quality,exclusivity and other hedonic values. Nonetheless, he arguedthat familiarity correlates negatively with the arousal level. As anillustration, when customers are repeatedly exposed to the sameproduct (-set), their appreciation and excitement decreases (Nelson& Meyvis [55]. Therefore, choosing a convenient time and strategyin presenting their products is a challenge for luxury companies.Likewise, selecting which features and attributes a product shouldhave is decisive. Moreover, the diversity of prosperous buyers, theirneeds, motivations and wishes makes the task more complex formanufacturers. For instance, car producers should simultaneously serve different tastes like environmental friendly clients withelectric/Hybrid vehicles, and people who seek the fundaments ofluxury with extravagant and exclusive cars. To summarize, unlikethe rational view, the arousal theory assumes that customers don’tknow what they want specifically. But they are trying to maintaintheir arousal level constant through the seek for newness (Garcia-Torres [49]). This postures a challenge for luxury car manufacturerswhile introducing electric cars. Additionally, the luxury literatureunderlies the role of price as a quality indicator for all customercategories (snob, Veblenian, Bandwagon & perfectionist). Thereexists a lower bound under which none of them would buy thegood because it is a harmful quality signal. Above this amount, thediverse groups are formed depending on their individual, socialand functional needs, and readiness to pay (Vigneron & Johnson,1999 [56]). Unlike the mass market, where the decision to acquirealternative fuel vehicles correlates positively with cost-savings (e.g.fuel & maintenance) Jansson [57], prosperous clientele is seekingexpensive goods with exceptional experiential aspects such assportiness.

H1b: prosperous buyers are willing to pay higher prices forperformed luxury EVs from favorite luxury car manufacturer.

The charging time and the range are functional attributesthat are decisive in the DM. In the mass market Hidrue et al. [44]found a negative effect of coming from a multicar household on thewillingness to buy electric vehicles. Similarly, and unlike what mostpeople would think (Flexibility: Prosperous buyers have access tomany cars. Therefore, they can switch between them depending ontheir needs), we reason that the same effect is present in the highendsegment. This clientele is experienced, seeks the fundamentsof luxuries and, have therefore higher standards and wishes.Independently, if they have 20 or 30 Hermès handbags in thewardrobe, the new one should not be minor to their possessions onany dimension (functional, social, individual and financial). Besides,it should be better at least in one fact. Similarly, someone who ownsa Ferrari, a Porsche and a Lamborghini is less likely to buy a newvehicle that has lower acceleration, range, etc. than his statusquo.This idea is also supported by various theories on innovationadoption where people are willing to buy the new product onlyif it shows better features (Jannsson, [57]. This is also consistentwith the luxury literature [4,46,6,47,48]) which highlights qualityaspects as a corner stone in the market.

• H2: improved functional aspects such as better range andshorter charging time correlate positively with the WTPfor luxury EVs from preferred luxury brand.

Also, the marketing of innovative products such as alternativefuel vehicles is always linked with subsidiaries (non- and monetary).Both government and companies encourage this in several wayslike unrestricted parking, tax- exemption and free charging. Theseattributes are important for this study to find out how they affectthe buying decision and how they correlate with the numberof cars in household as a mediator. Studies on the willingness tobuy electric cars in the mass market Hidrue et al. [44] showed theimportance of reducing battery costs and of introducing non- andmonetary subsidies on DM. This is understandable since thesemonetary advantages, evidently influence the utility function.Outgoing from luxury literature on buying motivations [56,58], onproduct definition and associations [46,48,59], financial and socialmotives like status and recognition are major buying motivations.For instance, there is a positive correlation between price andquality in the segment. Expensiveness implies superior quality.Therefore, we expect a minor effect of subsidies on the wtp forluxury EVs since this might be a bad quality signal.

• H3: The introduction of non- and monetary subsidies suchas tax exemption has little to no influence on the WTP forluxury EVs.

The Co2 emission is key aspect and a specification of BEVs.Therefore, it is essential to study its’ impact on the buying decision.According to the behavioral decision-making theories (chap. 3),customer ability to process information and his involvement havekey effect on his decision. Studying his/her willingness to pay forEVs vis-à-vis his/her engagement and appreciation for ecology,gives a wide view on the choice and helps marketers to betterunderstand the key motivations for ethics in luxury. It is thereforea combination of behavioral and economic perspectives to derivean appropriate estimation. Moreover, this allows to clarify theconflict within the luxury literature: On the other side, Ward andChiari, Davies et al. [60, 61] for example, sympathize sustainabilityas an exceptional and trendy marketing tactic, but don’t consider itdecisive like the fundamentals of luxuries. For instance, they citedmany arguments like the low-buying-frequency. People buy once aweek fair traded coffee bones and feel then helping others throughthis conscious behavior. However, they don’t buy a Rolex or aFerrari in the same tact. Additionally, the researchers proclaim theavailability of environmental friendly goods as well as their qualityas a feebleness. Finally, they argue that the purchase act is anintimate moment where only enjoyment and self-reward are majorfactors. On the one side, researchers like Bendell and Kleanthous,Kendall, Bendell, Wiedmann et al. and Kapferer [1,3,7,62,63]underlies ecology as key aspect in the segment. Furthermore, theywarn from ignoring it, even if customers don’t acclaim it openly.The authors showed that the appearance of new ecological luxuryconsumers like the LOHAS as well as the increasing demand forgreen products (from traditional buyers) makes ecology decisive inthe market. Nonetheless, a comparison between luxury fundamentswith the ecology principles showed numerous intersections. As anillustration, the fact that we should fairly handle with rare resourcesimplies a limited production that is also costly. As a result, we getexclusive products that have a good quality but also expensive whichoverlaps with luxury values. Besides, luxury start-ups like Tesla,Elivs &Kresse or Schilpachavan combine creativity, environmentalfriendliness with high-tech to get advantages and compete withmarket leaders. This pressure is continuously pushing establishedfirms to introduce similar concepts. As an illustration, luxury carmanufacturers started immediately the production of EVs whereasthe rest announced upcoming models with better features.

• H4: Prosperous buyers have high preference for Co2emission reduction.

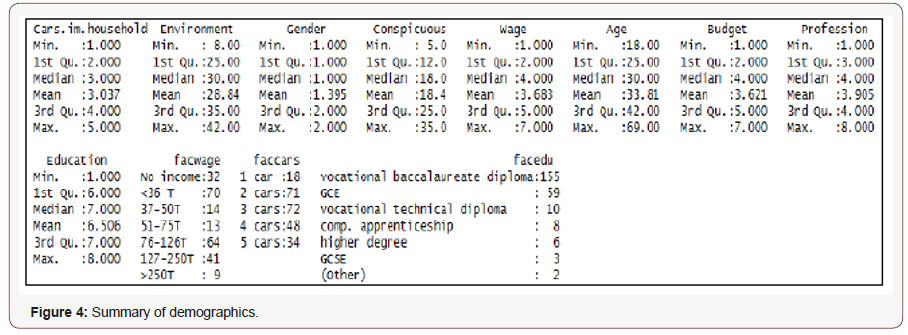

For this purpose, 243 luxury customers participated in thestudy (147 male and 97 female). Only respondents who wereplanning to buy a luxury car in the next 7-9 months were kept toget more realistic choices. At the beginning, they completed a setof questions on the luxury car they are more likely to purchase(from favorite brand). Moreover, the survey includes measuresof environmental friendliness and on materialism settled byHaws, Winterich and Naylor, and Eastman, Goldsmith and Flynn[64,65] respectively. The “green scale” contains 6 questions thatare evaluated on a 7-points Likert scale. The sum serves as anecology indicator. In the same way, the materialism level is definedthrough a reliable and valid question catalog. The collected dataincludes demographic information that are relevant to study thewillingness to pay for luxury electric vehicles. In addition to thestandard data like age, income and gender, the number of cars inhousehold, the education level and the budget dedicated to the nextpurchase were collected (Figure 4). Also, the education level is agood indicator for ecology, as well-educated people are more awareabout environmental issues and are therefore more likely to adapttheir behavior. The goal here is to find out if the ecology level is themain factor influencing the buying decision. Meaning if prosperousconsumers acquire EVs predominantly because of the low Co2emission or more due to values like (exclusivity, enjoyment, etc.)provided by luxury products. The number of cars serves then as amoderator since multicar households are supposed to be suppler.For example, they might use another vehicle if the charging takes toolong or when the trip clearly exceeds the battery capacity. Finally,people gave the amount they are dedicating for the car purchase.Combined with the output of the conjoint analysis the researchercan identify the consistency of the decision and which attributes(levels) are key aspects here. This is essential to model the choiceand to identify both churners and the churn causes within a luxurybrand (Figure 3,4).

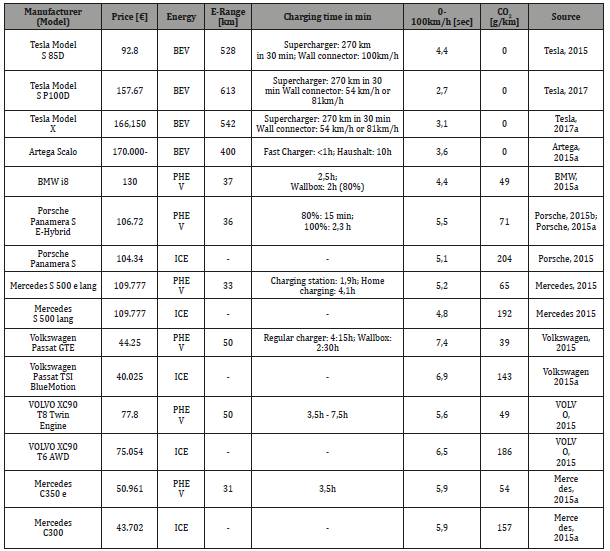

The respondents were given three models of their favoritecar, which they are willing to buy closely: a BEV, a PHEV and anICE. For the ICE cars, only price and performance were varying tostudy the hedonism effect in the decision-making: Buying (or not)EVs due sustainability or to luxury values such as trendiness andhigh acceleration. The questionnaire doesn’t mention concretemanufacturers since each respondent has a different favorite car andhis loyalty and brand relationship (involvement, love, attachment,etc.) is relative. For instance, both Ferrari and Porsche ownerslove their cars and enjoy their experiences, but they have differentrelations due to diverse brand facets. Furthermore, a none- choiceoptionis added to allow for churn prediction. When preferred manufacturers ignore ecology and sustainability, churners are thenmore likely to purchase other goods from their evoked set. In otherwords, they, voluntary, switch to a competitor that affords them thefunctional, individual and social values they are looking for. Eachrespondent was shown 17 choice cases and should pick up thealternative he is more likely to purchase. The attribute variationwas in percentage and relative to the basis version of that modelsince every participant has a different preferred car. Thus, theresult is more realistic and generalizable which implies consistency.Based on collected data from diverse manufacturers (Table 2), itbecomes clear which attribute levels are more realistic for theanalysis. All models within a category have similar characteristics.For instance, the average range is around 550 km (+- 10%) whichmatch with a combustion car. This is also the case of PHEV whenadding the electric range to the regular one. Moreover, numerousmanufacturers have special charging stations where around 80% ofbattery capacity is reached in less than 30 min. However, people havethe domicile charging option which obviously has lower efficacy.Integrating this option in the conjoint analysis is indispensable sincepeople feel more comfortable charging their cars at home. Also, thereachability and the geographical distribution of charging stationsis still an issue especially in villages. Contrasting the theories ofdisruptive innovations [66,67] that undertake the idea of lowerprice and inferior quality for the new good, luxury EVs are fasterand more expensive than numerous luxury vehicles. For example,the Tesla Model S P100D costs around €157.670 and goes from 0 to100 Km/h in 2,7 seconds (Table 2). A Mercedes S560 4Matic has aprice of €116,994 and a speeding up of 4,6 seconds from 0 to 100km/h (Mercedes- Benz, 2017) (Table 2).

Table 2:Conventional premium-luxury ICEs EVs and PHEVs.

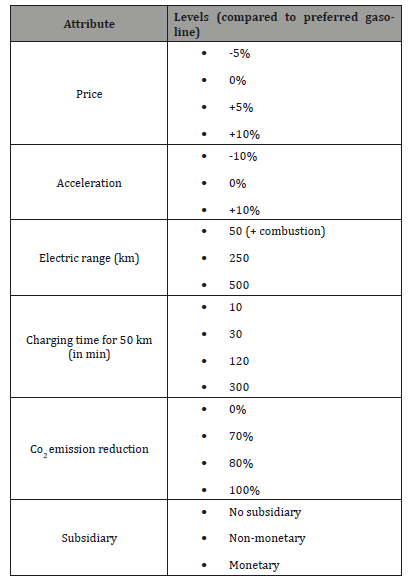

The Co2 emission is decisive in this study since it plays amoderating role in indicating the type of the car. A 100% and a0% emission represent an ICE and an EV respectively. It was alsocompulsory to introduce 2 other values for the PHEV to see the effect of a minimal amelioration on choices. Table 3 summarizesthe attributes and their levels. For the utility computation, thelowest level (for example - 5% for the price/ 50 km for electricrange) was set to zero. Subsequently, all estimators are relative toan amelioration/augmentation (Table 3).

Table 3:Attributes and their shaping

Data Groundwork and Utility Computation

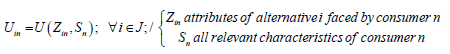

In discrete choice models, preferences are represented byutility functions.

Mathematically:

The decision rule is therefore explained by choosing thealternative i with the highest utility among all options

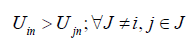

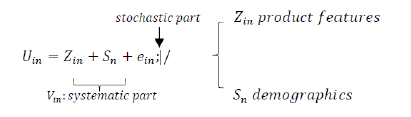

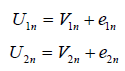

The utility can be therefore decomposed into:

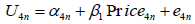

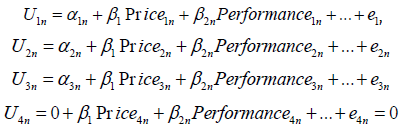

In case of two brands (easiest situation), the utility functionsare expressed as follows:

In this study, there are 3 products and the nonchoiceoption. Consequently, there are four utilities (1 for each choice). is set to zero to compute otherutilities relative to the churning option since only difference inutility matters. In summary:

is set to zero to compute otherutilities relative to the churning option since only difference inutility matters. In summary:

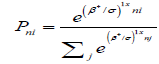

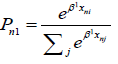

The choice probability (logit) is expressed by

However, the parameter is called scale parameter since allcoefficients are scaled by  to reflect the variance of the unobservedpart of the variables Train [26].

to reflect the variance of the unobservedpart of the variables Train [26].

Subsequently only the ratio  is estimable not theindividual level which implies the standard logit expression:

is estimable not theindividual level which implies the standard logit expression:

Results interpretation

Before running the model estimation, it was necessary tochoose a convenient set of parameters. The Bayesian literaturesuggest the number of draws to be above 1000 draws to haveefficient estimations RStan [68]. Additionally, using multiple chainsis highly recommendable since having both various chains andsufficient draws allow the researcher to better judge the model and,see multiple chain convergence. It is important to mention that Stanuses a stochastic algorithm and so, the results will not be identicaleven with repetition using same parameters and starting values. Inthis case, after trying some combinations like 4 chains and 3000iterations or 2 chains and 1000 iterations, the choice was to use 3chains and 3000 draws due to a good mixture of computing timeand results. The ggmcmc package was used because it providesmultiple tools, so that their combination gives a precise indicationof lack of convergence and, gives clues how to fix it:

Formal

• : ggmcmc provides a potential scale reduction factoras one of the most valuable tool for chain convergence.

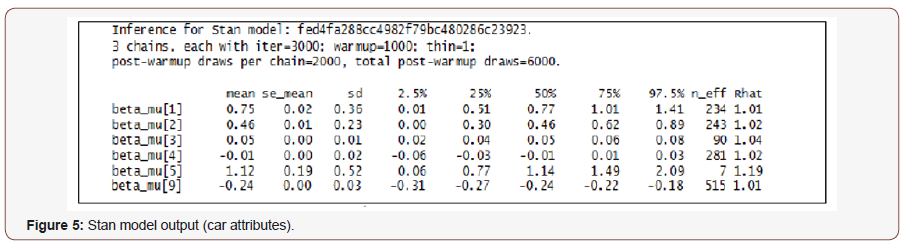

: ggmcmc provides a potential scale reduction factoras one of the most valuable tool for chain convergence. relies on different chains for the same parameterthrough a comparison of both a within and a betweenchain variation. Therefore, it is expected to be close to1 in the ideal case. The first 5 parameters are the price,performance in terms of acceleration, electric range,charging time and Co2 emission reduction respectively. Beta_mu [9] describes the subsidiary variable. Thesequences appear to have mixed well. The estimatedpotential scale reduction factors

relies on different chains for the same parameterthrough a comparison of both a within and a betweenchain variation. Therefore, it is expected to be close to1 in the ideal case. The first 5 parameters are the price,performance in terms of acceleration, electric range,charging time and Co2 emission reduction respectively. Beta_mu [9] describes the subsidiary variable. Thesequences appear to have mixed well. The estimatedpotential scale reduction factors  ~1 for all theparameters and quantile of interest displayed (Figure 5).

~1 for all theparameters and quantile of interest displayed (Figure 5).

• Gewecke z-scores: stresses the contrast between thebegin and the last part of a chain. More precisely, the testis a frequentist comparison of the means. Subsequently,the result should lay between -2 and 2 (Fernandez, 2016).This area allows to check for problematic chains. In thiscase, it was difficult to identify the area only for theseparameters since the model computes also coefficients atthe individual level (243*9).

• N_eff is a random variable estimated from the simulationdraws. The one with higher effective sample size haslower standard errors of the mean and more stableestimates. This choice guarantees the highest n_eff(Figure 5) values among all other alternatives (highestvalues here compared to pretests with 4 chains and 3000iterations) (Figure 5).

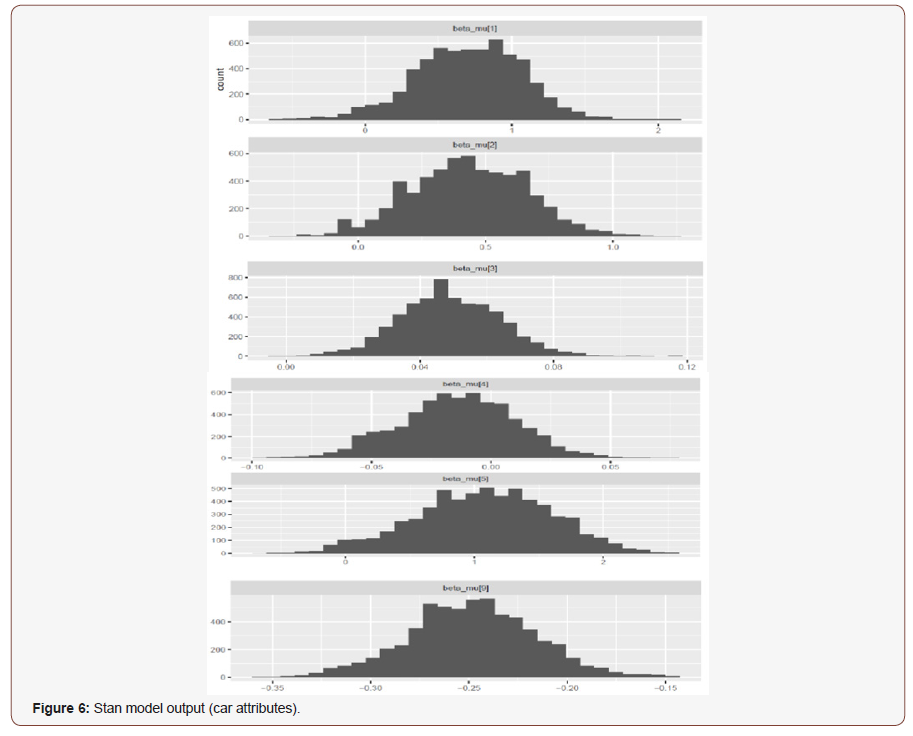

Histograms/density plots/ full and partial chain comparison

Histograms present the posterior distribution and combinethe values of all chains. Nonetheless, it is only a general view of thedistribution and the posterior shape, not a convergence plot. Theprice histogram shows a bell-shaped distribution in the positiveinterval (Figure 6). This is consistent with the fundamentals ofluxuries. Prosperous buyers are accepting expensive cars becausethey signalize high quality and exclusivity aspects. Furthermore,customers dedicate high budgets for the vehicle purchase since it isthe best mean to project prosperity and status. In conclusion, luxurybuyers are accepting soaring prices from favorite manufactures toenjoy the experience of driving their dream cars. This implies, thathigher prices won’t prevent clients from acquiring their favoritevehicle (other luxury values and features should be guaranteed).Besides, the majority were ready to pay between 5 and 10% moreto get a sophisticated vehicle from their favorite manufacturer. Thisis primary for the hole industry: first, it shows that the segmentis characterized through a high loyalty level. Second, it indicatesa market research deficiency. Numerous companies need to bemore sophisticated and not only produce cars that meet customerneeds, but a touch above (in all dimensions: functional & hedonic).Primary is then an appropriate application of prestige pricing. Incontradiction to previous investigations, expensiveness in the luxurycar industry won’t prevent clients to purchase their preferred car,it is more likely to enhance their interest. In summary, high pricesare significantly related with key aspects such as quality, aesthetics,status and enjoyment (Figure 6).

Acceleration have also a positive distribution. This is consistentwith the fundaments of luxury where functional dimensionsare decisive. For instance, fast vehicles have improved features,quality and are more sophisticated. Sportiness in terms ofacceleration makes the driving experience more enjoyable andpleasant. Subsequently, the hedonic component will increase, theluxuriousness feelings and the arousal level expand. Besides, thedistribution of the range preferences is commonly positive whichinfers that prosperous consumers are preferring performed vehicleswith a range comparable to combustion ones. Unlike some guesseslike prosperous buyers have numerous cars and therefore, theycan use another vehicle if the travel distance exceeds the batterycapacity, this study shows the indispensability of large ranges intheir DM. This is also consistent with the luxury definition as wellas with the adoption theories where the new car should show, atleast, similar (& better) features as their status-quo. Subsequently,luxury buyers are used to higher standards and values which can’tbe disregarded or neglected. As long as manufacturers guaranteethese performances and values, there is no reason for switchingto competitors. Beta_mu [4] indicates the impact of extendedcharging time which is, as expected, mostly negative. However,some respondents were accepting longer charging processes whichmight be due to a limited usage (multicar) and/or to the limitedconcurrence at this time. Also, the trendiness and the nature ofsome luxury buyers who are innovative and seek primary novelgoods might be a good clarification of this partial preference. Forexample, some clients are more flexible and can use another vehicleif the charging time gets longer. However, this should not exceed acertain time window. Hence, luxury manufacturers have the defyto develop new techniques and strategies that smooth a strongpresence in the new market.

Regarding the reduction of Co2 emission (beta_mu[5]), theoutput shows the highest respondent preferences. The appearanceof environmental friendly customers such as the LOHAS andthe millennials strengthens the preference for ecological cars.Moreover, more and more traditional Luxury buyers are gettingaware of environmental issues. This consciousness results in anadaption behavior like acquiring “green” goods. Unlike the resultspresented by various researchers like Davies et al. [61], prosperouscustomers show a high consciousness about environmental issueswithout snubbing the benefits of luxuries. Regardless of theirmotivations and incentives (intrinsic vs. extrinsic; ecology vs.materialism) all customers show a high preference for “green”driving. Accordingly, ignoring ecology and sustainability in thehigh-end market outcomes a total disaster for producers. Therefore,finding the right recipe including ecology and luxury characteristicssuch as enjoyment is a key for success in the future market. Also, thedata shows immense opportunities for established firms througha strong existing loyalty and deep brand relationships (love,attachment, etc.) to maintain customers and good market shares.The last estimated parameter is the preference for subsidiary (nonandmonetary). Beta_mu[9] is negatively bell-shaped distributed.Studies of Davies et al. [61], Jannsson [58] showed the importanceof these incentives in the mass market. Customers were interestedin EVs primary due to cost savings (maintenance) and otherfinancial incentives (tax exemption, etc.). However, prosperousbuyers don’t care about the peripheral governmental advantagesthey can get through purchasing ecological products. For instance,using bus lines, free parking or tax exemption don’t incentive themand are not decisive in the decision- making. This is consistentwith the understanding of luxury which relies on exclusivity,rarity, enjoyment and extraordinariness. Consequently, unlike themass market, wealthy consumers fully ignore these measures.Subsequently, all the hypothesis are confirmed and deep-rooted.

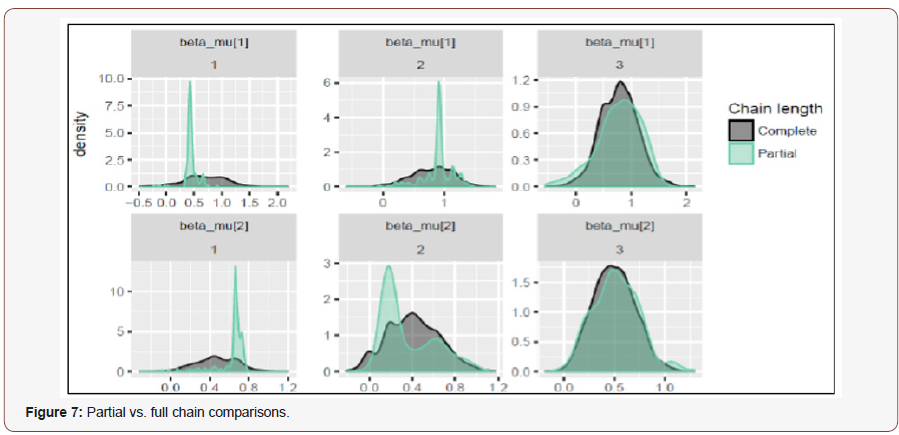

The density plot has the advantage that the researcher cancompare the chains and if they converged in a similar space dueto distinct colors. the density plots for price and Performanceestimations show a high chain convergence and that all threechains converged in the same interval. This is the case for allother attributes which, due to limited space, are not includedhere. In the same context of overlapping densities, ggmcmc allowsto compare the last part of the chain (last 10%) with the wholechain. Commonly, they should be sampling in the same direction,meaning, the overlapped densities should be similar. Continuingwith the first 2 attributes, price and performance, the last part hasgenerally the same tendency as the whole chain, especially for 2ndand 3rd chains (Figure 7).

All other attributes have similar characteristics.

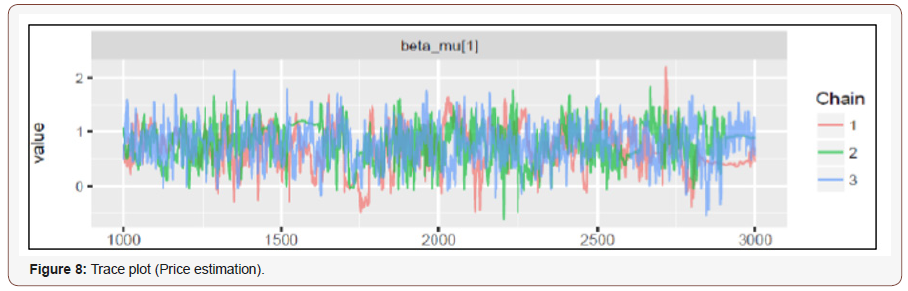

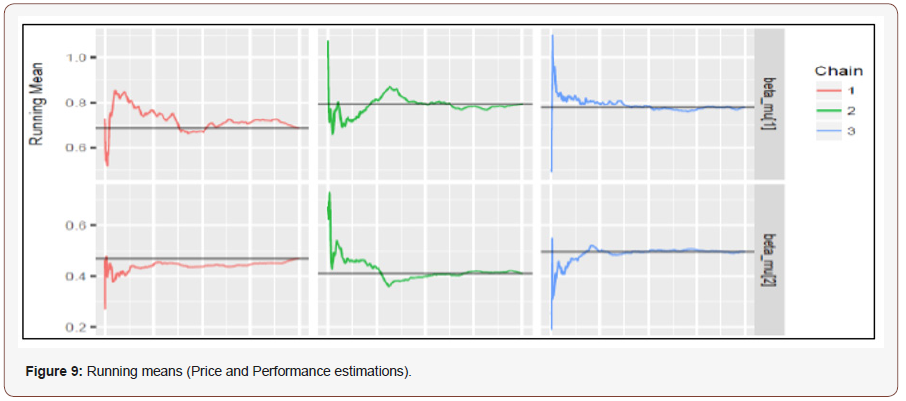

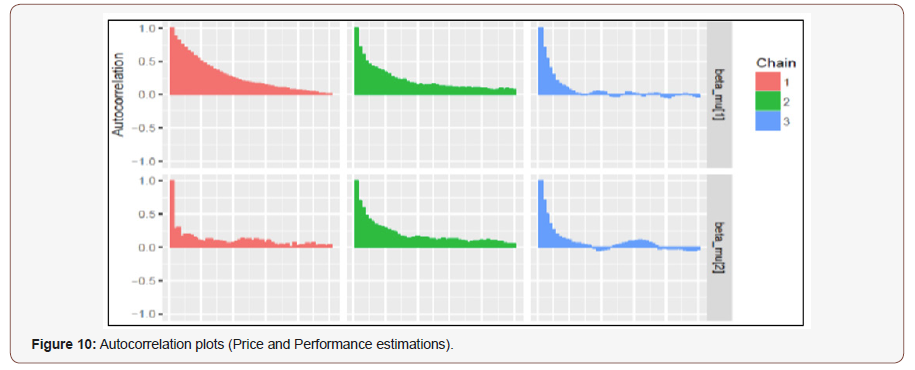

Trace plots/running means/autocorrelations

Trace plots are an essential part for evaluating convergence anddiagnostic chain issues. It allows to see the time series of the samplingprocess. Important, is to have a random walk and not a tendencywhich implies a lack of convergence. In this case, all three chainshave mixed very well and follow a random sampling way (Figure 8).The distinct colors allow the between chain comparison. Anotherway to judge the efficiency is the speed of the chain convergence,a plot with the running means. This is helpful to study the withinchain convergence issues. The outcome is as expected, a horizontalline that quickly approaches the global mean, and all chains havecomparable means (Figure 9). Furthermore, the autocorrelationplot of the chains is a powerful tool to assess the quality of thechain. The outcome is a bar in the first lag (at 1) and converges tozero (Figure 10). Most of the chains seem to have a good behaviorand, so guarantee good estimations. However, autocorrelation isnot definitively a bad signal such as lack of convergence might bean indicator of chain/ parameter misbehavior. It also indicates thata chain needs more time to converge than others. In conclusion,all chains for the 6 car attributes have converged very well andthe formal diagnostic tools ( ientresults. Accordingly, luxury car buyers (independent of number ofcars) are very interested in EVs and are willing to pay considerableamounts for performance in terms of acceleration and electricalrange. Furthermore, they prefer lower Co2 emission which implies ahigh consciousness level. This is consistent with current researcheswhich highly recommend ecology and sustainability in luxuries,even if the customer doesn’t acclaim it openly [1,3,6,69,70].Subsequently, ignoring such aspects would prevent clients to buytheir favorite brands and so, voluntary churn. Also, long chargingtimes are less preferred despite that clients come from multicarhouseholds. Luxury electric vehicle producers, should performboth battery capacity and efficiency. These are crucial featurestoward achieving competitive advantages. The finding is primaryfor manufacturers and, especially market leaders such as Daimler,Porsche, Ferrari etc. since it shows a high customer loyalty level.However, finding a good mixture of indulgence, trendiness in termsof ecology and functional values is the recipe for a lasting success.Most prosperous clients show a high to absolute loyalty. There isno reason for churning and switching to competitors if the favoritecar fabricator fulfills their wishes and assures luxury values suchas exclusivity (soaring prices up to 10% compared to combustioncars) and tall quality (acceleration & aestetics), and an ecologicalcomponent (reduction of Co2 emission) (Figure 8-10).

ientresults. Accordingly, luxury car buyers (independent of number ofcars) are very interested in EVs and are willing to pay considerableamounts for performance in terms of acceleration and electricalrange. Furthermore, they prefer lower Co2 emission which implies ahigh consciousness level. This is consistent with current researcheswhich highly recommend ecology and sustainability in luxuries,even if the customer doesn’t acclaim it openly [1,3,6,69,70].Subsequently, ignoring such aspects would prevent clients to buytheir favorite brands and so, voluntary churn. Also, long chargingtimes are less preferred despite that clients come from multicarhouseholds. Luxury electric vehicle producers, should performboth battery capacity and efficiency. These are crucial featurestoward achieving competitive advantages. The finding is primaryfor manufacturers and, especially market leaders such as Daimler,Porsche, Ferrari etc. since it shows a high customer loyalty level.However, finding a good mixture of indulgence, trendiness in termsof ecology and functional values is the recipe for a lasting success.Most prosperous clients show a high to absolute loyalty. There isno reason for churning and switching to competitors if the favoritecar fabricator fulfills their wishes and assures luxury values suchas exclusivity (soaring prices up to 10% compared to combustioncars) and tall quality (acceleration & aestetics), and an ecologicalcomponent (reduction of Co2 emission) (Figure 8-10).

Afterwards, the introduction of consumer characteristicssuch as Demographics and measures of both environmentalfriendliness and materialism is beneficial to get consistent andreliable estimations. The model computes coefficients on theindividual level for every car type (EV,PHEV & ICE). To this issue,a Caterpillar plot is drawn to get better elucidations since it showsthe general pattern of the results through ordering the Variablesby effect magnitude. The result shows high effect of the income forall car types.  . Surprisingly, is that allvariables have similar influence and appreciation among all threecar variations

. Surprisingly, is that allvariables have similar influence and appreciation among all threecar variations  . This means, there is no clearpreference pattern or big differences among luxury customers thatcan clearly predict their choices for a concrete car type. This mightbe due to the choice situations where the randomly presentedattribute levels don’t favorize one type over the other. This might bedue to the lack of specific brands since we didn’t introduce specificmanufacturers in the survey. The generalizability of the study aswell as the diversity of the brands and their values are major factors.Nonetheless, the output recognizes the reduction of Co2-emissionas highest and most preferable attribute which, implicitly means

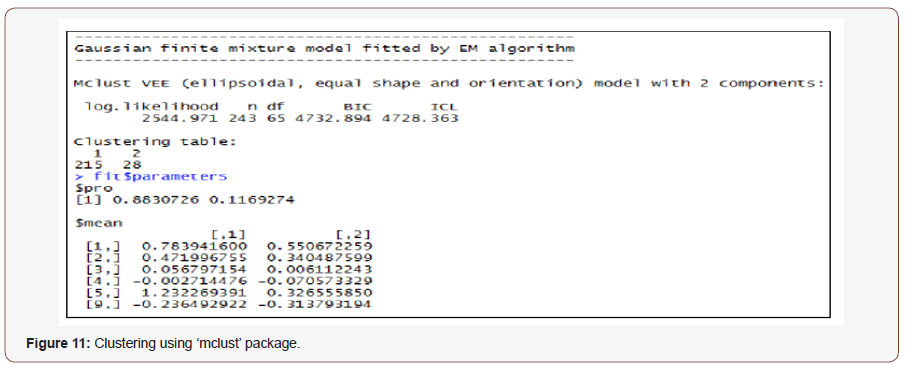

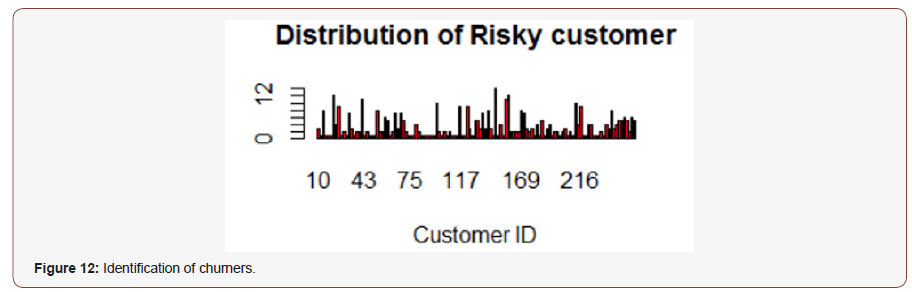

. This means, there is no clearpreference pattern or big differences among luxury customers thatcan clearly predict their choices for a concrete car type. This mightbe due to the choice situations where the randomly presentedattribute levels don’t favorize one type over the other. This might bedue to the lack of specific brands since we didn’t introduce specificmanufacturers in the survey. The generalizability of the study aswell as the diversity of the brands and their values are major factors.Nonetheless, the output recognizes the reduction of Co2-emissionas highest and most preferable attribute which, implicitly means  (under the assumption that other luxuryvalues are guaranteed). Toward testing this finding, a cluster analysiswould be an appropriate tool since the model estimates coefficientson the individual level (each person on each car attribute).Explicitly, a Model based approach because it assumes a variety ofdata models and applies maximum likelihood estimation and Bayescriteria to identify the most likely model and number of clusters.Specifically, the Mclust (Figure 11) function in the ‘mclust’ packagein R selects the optimal model according to BIC for EM initialized byhierarchical clustering for parameterized Gaussian mixture models(Package ‘mclust’, [71]. The output is consistent with the Caterpillarplot. It suggests two groups which are unbalanced (around 88%of respondents in the first group). Moreover, comparing theaverage values for each cluster on every vehicle attribute, showssimilar preferences with a minimal difference in their intensities.For example, both groups prefer expensive performed cars butthe first one has tougher requirements for acceleration, electricrange and Co2 emission reduction. However, the second group issomehow agiler in dealing with extended charging times and with the introduction of subsidiaries [72-80]. In a further step, we triedto both identify churners as well as the specific cases where theydecided not to buy (Figure 12) [81-86]. The decision was to focuson people who picked up ecological products (PHEV & EV) less than50% (in 5 cases there were only combustion cars) among all 12(17-5) choice situations [87-95]. The analysis confirms that thosewere churning due to a lack of quality aspects such as lower rangeand longer charging time. They built the second cluster with thetougher quality requirements [96-100] (Figure 11,12).

(under the assumption that other luxuryvalues are guaranteed). Toward testing this finding, a cluster analysiswould be an appropriate tool since the model estimates coefficientson the individual level (each person on each car attribute).Explicitly, a Model based approach because it assumes a variety ofdata models and applies maximum likelihood estimation and Bayescriteria to identify the most likely model and number of clusters.Specifically, the Mclust (Figure 11) function in the ‘mclust’ packagein R selects the optimal model according to BIC for EM initialized byhierarchical clustering for parameterized Gaussian mixture models(Package ‘mclust’, [71]. The output is consistent with the Caterpillarplot. It suggests two groups which are unbalanced (around 88%of respondents in the first group). Moreover, comparing theaverage values for each cluster on every vehicle attribute, showssimilar preferences with a minimal difference in their intensities.For example, both groups prefer expensive performed cars butthe first one has tougher requirements for acceleration, electricrange and Co2 emission reduction. However, the second group issomehow agiler in dealing with extended charging times and with the introduction of subsidiaries [72-80]. In a further step, we triedto both identify churners as well as the specific cases where theydecided not to buy (Figure 12) [81-86]. The decision was to focuson people who picked up ecological products (PHEV & EV) less than50% (in 5 cases there were only combustion cars) among all 12(17-5) choice situations [87-95]. The analysis confirms that thosewere churning due to a lack of quality aspects such as lower rangeand longer charging time. They built the second cluster with thetougher quality requirements [96-100] (Figure 11,12).

Conclusion

This work investigates the willingness to buy luxury EVs fromthe favorite car manufacturers. Furthermore, it aims to modelthe churn risk if producers ignore important aspects such assustainability and ecology. Concrete brands were ignored due tothe difficulty to, first cover all luxury car manufacturers in onestudy and second, to get sufficient luxury customers for eachmanufacturer and so, to get a representative sample. Also, thisallows to get a generalizable model. To conclude, prosperous buyersare generally environmentally friendly and, are therefore readyto adapt their behavior in a conscious way. However, spendingenormous amounts on green products should guarantee someluxury benefits such as enjoyment and exclusiveness. The studyshows that regardless of the individual ecology/materialism level,all customers are strongly preferring lower Co2 emission. Moreover,acceleration and soaring prices were significant factors influencingthe decision making. This is consistent with the fundamentals ofluxury in terms of high quality, high price, extraordinariness, etc.Also, the cluster analysis using coefficients for both individualand alternative specific variables show high preference similarityamong all luxury customers. The finding is primary for establishedluxury car manufacturers to keep their customers loyal and, toguarantee a leading market position. Producing EVs in the highendsegment has enormous potential and a huge effect on firms’success and survive. Nevertheless, not only product and customer’characteristics are relevant factors influencing the decisionmakingand, subsequently the loyalty, but also the brand value issignificant. A Ferrari as an example offer their owners completelydifferent values and sensations than a Mercedes, a BMW or even aPorsche, and vice versa.

This massive acceptability for luxury ecological automobilesmight also originate from the nature of prosperous buyers whoare constantly seeking for trendy and new extravagant productsthat keep them privileged and guarantee a high arousal level.Additionally, such green products are well accepted and gladlyseen. Accordingly, a high social status. Concerning churners,depending on the brand value and strength, their departing mightbe considered a consumption break. This could only be the casefor some leading firms and under certain assumptions (update,catch up. Superiority and preeminence in short time). According to Nelson and Meyvis [55], interrupting a pleasant experiencereduces adaptation (familiarity) which implies a tall arousallevel. Consequently, it makes the consumption experience moreenjoyable after that break. Analogous, if customers enjoyed theircurrent luxury car and switch to competitor just for change andnot due to remarkably superior features, they are more likely tohave an unpleasant experience with the new vehicle. The changeis to some extent the break. Afterwards, churners will identify thesuperiority of their favorite manufacturers, appreciate it more, andsubsequently reemerge. Their consumption experience shouldthen be more enjoyable than before the intermission. However, ifthe churn is purely because of significant minor quality aspects(second group with tougher requirements), they are less likely tocome back, especially if the new brand pleasingly fulfill their needs.

Acknowledgement

None.

Conflict of Interest

No conflict of interest.

References

- Bendell J, Kleanthous A (2007) Deeper Luxury: Quality and Style When the World Matters.

- Kapferer JN (2010) The new strategic brand management: creating and sustaining brand equity long term (4th). Kogan Page, London, UK.

- Kapferer JN, Michaut A (2014) Is Luxury Compatible with Sustainability? Luxury Consumers Viewpoint. Journal of Brand Management 21(1): 1-22.

- Dubois B, Laurent G (1994) Attitudes Towards the Concept of Luxury: an Exploratory Analysis. AP-Asia Pacific Advances in Consumer Research. Joseph A Cote, Siew Meng Leong, Provo (Eds.), UT: Association for Consumer Research, pp. 273-278.

- Dubois B, Czellar S, Laurent G (2005) Consumer Segments Based on Attitudes Toward Luxury: Empirical Evidence from Twenty Countries. Marketing Letters 16(2): 115-128.

- Wiedmann KP, Hennings N, Siebels A (2007) Measuring Consumers Luxury Value Perception: A Cross-Cultural Framework. Academy of Marketing Science 7(7): 1-20.

- Hennigs N, Wiedmann KP, Klarmann C, Behrens S (2013) Sustainability as Part of the Luxury Essence: Delivering Value through Social and Environmental Excellence. Journal of Corporate Citizenship 52(11): 25-35.

- Pollak RA (1970) Habit Formation and Dynamic Demand Functions. Journal of Political Economy 78(4): 745-763.

- Garcia Torres MA (2009) Consumer Behavior: Evolution of Preferences and The Search for Novelty. United Nations University, Tokyo, Japan.

- Schmitt B, Brakus JJ, Zarantonello L (2015) From experiential psychology to consumer experience. Journal of Consumer Psychology 25(1): 166-171.

- Cretu AE, Brodie RJ (2007) The influence of brand image and company reputation where manufacturers market to small firms: A customer value perspective. Industrial Marketing Management 36(2): 230-240.

- Zaichkowsky JL (1985) Measuring the Involvement Construct. Journal of Consumer Research 12(3): 341-352.

- Thomson M, MacInnis D, Park C (2005) The ties bind: Measuring the strength of consumers emotional attachments to brands. Journal of Consumer Psychology 15(1): 77-91.

- Aaker J (1997) Dimensions of Brand Personality. Journal of Marketing Research 34(3): 347-356.

- Graeff TR (1997) Consumption situations and the effects of brand image on consumers brand evaluations. Psychology and Marketing 14(1): 49-70.

- Salinas EM, Perez JMP (2009) Modeling the brand extensions influence on brand image. Journal of Business Research 62(1): 50-60.

- Aaker J (1999) The Malleable Self: The Role of Self-Expression in Persuasion. Journal of Marketing Research 36(1): 315-328.

- Grohmann B (2009) Gender dimensions of brand personality. Journal of Marketing Research 46(1):105-119.

- Dusenberry JS (1952) Income, Saving, and the Theory of Consumer Behavior. Harvard University Press: Cambridge, US.

- Pollak RA (1970) Habit Formation and Dynamic Demand Functions. Journal of Political Economy 78(4): 745-763.

- Lancaster KJ (1966) A New Approach to Consumer Theory. The Journal of Political Economy 74(2): 132-157.

- Hawkins SA, Hoch SJ (1992) Low-involvement learning: Memory without evaluation. Journal of Consumer Research 19(2): 212–225.

- Malar L, Krohmer H, Hoyer WD, Nyffenegger B (2011) Emotional Brand Attachment and Brand Personality: The Relative Importance of the Actual and the Ideal Self. Journal of Marketing 75(4): 35-52.

- Berry S, Levinsohn J, Pakes A (1995) Automobile Prices in Market Equilibrium. Econometrica 63(4): 841-890.

- Brwonstone D, Bunch DS, Train K (2000) Joint mixed logit models of stated and revealed preferences for alternative-fuel vehicles. Transportation Research Part B: Methodological 34(5): 315-338.

- Train K (2002) Discrete Choice Methods with Simulation. National Economic Research Associates: Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK.

- Alba J, Hutchinson JW (1987) Dimensions of Consumer Expertise. Journal of Consumer Research 13(4): 411-454.

- Johar GV, Pham MT (1999) Relatedness, prominence, and constructive sponsor identification. Journal of Marketing Research 36(3): 299-312.

- MacInnis DJ, Jaworski BJ (1989) Information processing from advertisements: towards an integrative framework. J Mark 53(4): 1-23.

- Hadden H, Tiwari A, Roy R, Ruta D (2007) Computer assisted customer churn management: State-of-the-art and future trends. Computers and Operations Research 34(10): 2902-2917.

- Liu DR, Shih YY (2004) Hybrid approaches to product recommendation based on customer lifetime value and purchase preference. The Journal of System and Software 77(2): 181-191.

- Kim HS, Yoon CH (2004) Determinants of subscriber churn and customer loyalty in the Korean mobile telephony market Determinants of subscriber churn and customer loyalty in the Korean mobile telephony market. Telecommunications policy 28(9-10): 751- 765.

- Kim M, Park JE, Dubinsky AJ, Chaiy S (2012) Frequency of CRM implementation activities: a customer‐centric view. Journal of Services Marketing 26(2): 83-93.

- Burez J, Van den Poel D (2007) CRM at a pay-TV company: Using analytical models to reduce customer attrition by targeted marketing for subscription services. Expert Systems with Applications 32(2): 277-288.

- Van den Poel D, Lariviere B (2004) Customer attrition analysis for financial services using proportional hazard models. European Journal of Operational Research 157(1): 196-217.

- Bower JB, Christensen CM (1995) Disruptive Technologies: Catching the Wave. Harvard Business Review 43-53.

- Bower JB, Christensen CM (1995) Disruptive Technologies: Catching the Wave. Harvard Business Review 43-53.

- Adner R (2002) When are technologies disruptive? a demand-based view of the emergence of competition. Strat Mgmt J 23(8): 667-688.

- Wei C, Chiu I (2002) Turning telecommunications call details to churn prediction: a data mining approach. Expert Systems with Applications 23(2): 103-112.

- Albert JH, Chib S (1993) Bayesian analysis of binary and polychotomous response data. Journal of the American statistical Association 88(422): 669-679.

- McCulloch R, Rossi E (1994) An exact likelihood analysis of the multinomial probit model. Journal of Econometrics 64(1-2): 207-240.

- Cameron AC, Trivedi PK (2005) Microeconometrics Methods and Applications. Cambridge CB2 2RU, UK.

- Bain & Company (2016) Luxury Goods Worldwide Market Study.

- Hidrue MK, Parsons GR, Kempton W, Gardner MP (2011) Willingness to pay for electric vehicles and their attributes. Resource and Energy Economics 33(3): 686-705.

- Petschnig M, Heidenreich S, Spieth P (2014) Innovative Alternatives Take Action - Investigating Determinants of Alternative Fuel Vehicle Adoption. Transportation Research Part A: Policy and Practice 61: 68-83.

- Dubois B, Czellar S, Laurent G (2005) Consumer Segments Based on Attitudes Toward Luxury: Empirical Evidence from Twenty Countries. Marketing Letters 16(2): 115-128.

- Heine K (2012) The Concept of Luxury Brands.

- Langer D, Heil O (2013) Luxury Marketing & Management. Center for Luxury Research: Mainz, Germany.

- Garcia Torres A (2004) Consumer Behavior: utility maximization and the seek for novelty. Maastricht University, Netherlands.

- Johnson Laird PN, Girotto V, Legrenzi P (2004) Reasoning from inconsistency to consistency. Psychological Review 111(3): 640-661.

- Legrenzi P, Umita C (2011) Neuromania: On the Limits of Brain Science. Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK.

- Hebb DO (1955) Drives and the C. N. S. (conceptual nervous system). Psychological Review 62(4): 243-254.

- Berlyne DE (1970) Novelty, complexity, and hedonic value. Percept & Psychophys 8(5): 279-286.

- Berlyne DE (1960) Conflict, arousal, and curiosity. New York, US.

- Nelson LD, Meyvis T (2008) Interrupted Consumption: Disrupting Adaptation to Hedonic Experiences. Journal of Marketing Research 45(6): 654-664.

- Vigneron F, Johnson LW (1999) A review and a conceptual framework of prestige-seeking consumer behavior. Academy of Marketing Science Review (1): 1-18.

- Jansson J (2011) Consumer eco-innovation adoption: assessing attitudinal factors and perceived product characteristics. Bus Strategy Environ. 20(3): 192-210.

- Leibenstein Harvey (1950) Bandwagon, Snob and Veblen Effects in the Theory of Consumer Demand. Quarterly Journal of Economics 64(2): 183-207.

- Meffert H, Lasslop I (2004) Luxusmarkenstrategie. Bruhn M (Ed.), Handbuch Markenführung, Wiesbaden, Germany.

- Ward D, Chiari C (2008) Keeping Luxury Inaccessible. European School of Economics: MRPA (Munich Personal RePEc Archive).

- Davies IA, Lee Z, Ahonkhai I (2012) Do Consumers Care About Ethical Luxury? Journal of Business Ethics 106(1): 37-51.

- Kndall J (2010) Responsible luxury: A report on the new opportunities for business to make a difference. CIBJO (Confederation internationale de la Bijouterie, Joaillerie et Orfevrerie): The World Juwellery.

- Bendell J (2012) Elegant disruption: how luxury and society can change each other for good. Asia Pacific Center for Sustainable Enterprise Queensland.

- Haws KL, Winterich KP, Naylor RW (2010) Seeing the World Through Green-Tinted Glasses: Motivated Reasoning and Consumer Response to Environmentally Friendly Products. Journal of Macromarketing 5(2): 18-39.

- Eastman JK, Goldsmith RE, Flynn LR (1999) Status Consumption In Consumer Behavior Theory: Scale Development And Validation. Journal of Marketing Theory and Practice 7(3): 41-52.

- Bower JL, Christensen CM (1995) Disruptive Technologies: Catching the Wave. Harvard Business Review 73(1): 43-53.

- Christensen CM (1997) The Innovator's Dilemma: When New Technologies Cause Great Firms to Fail. Boston, US.

- Rstan (2017) Found under: https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/rstan/vignettes/rstan.html.

- Hoffman MD, Gelman A (2014) The No-U-Turn Sampler: Adaptively Setting Path Lengths in Hamiltonian Monte Carlo. Journal of Machine Learning Research 15: 1593-1623.

- Cvijanovich M (2011) Sustainable Luxury: Oxymoron? Lecture in Luxury and Sustainability.

- Package mclust (2017) Gaussian Mixture Modelling for Model-Based Clustering, Classification, and Density Estimation. Found under: https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/mclust/mclust.pdf.

- Allen CT, Madden TJ (1985) A Closer Look at Classical Conditioning. The Journal of Consumer Research 12(3): 301-315.

- Barry TE, Howard DJ (1990) A Review and Critique of The Hierarchy of Effects in Advertising. International Journal of Advertising 9(2): 98-111.

- BMW (2015) Found under: http://www.bmw.de/de/neufahrzeuge/bmw-i.html.

- Feinberg R (1986) Credit Cards as Spending Facilitating Stimuli: A Conditioning Interpretation. Journal Of Consumer Research 13(3): 348-356.

- Fernandez IM (2019) Using the ggmcmc package.

- Gelman A, Jakulin A, Pittau MG, Su YS (2008) A Weakly Informative Default Prior Distribution for Logistic and other Regression Models. The Annals of Applied Statistics 2(4): 1360-1383.

- Langer EJ (1983) The Psychology of Control. Behavioral and Cognitive Psychotherapy 14(2): 311.

- Lewis A, Webley P, Furnam A (1995) The New Economic Mind, 2, Prentice Hall.

- Marschak J (1960) Binary Choice Constraints on Random Utility Indicators. K Arrow (Ed.), Stanford Symposium on Mathematical Methods in the Social Sciences.

- Marshall A (1890) Principles of Economics. In Westing HJ, Albaum G (1975) Modern Marketing Thought 3, Collier Macmillan Publishers.

- McFadden D (1974) Conditional logit analysis of qualitative choice behavior.

- McFadden D (1978) Econometric Models of Probabilistic Choice.

- McFadden D (1987) Regression-based specification tests for the multinomial logit model. Journal of Econometrics 34(1-2): 63

- Pachauri M (2001) Consumer Behavior: A Literature Review. The Marketing Review 2(3): 319-355.

- Peter JP, Nord WR (1982) A Clarification and Extension of Operant Conditioning Principles in Marketing. Journal of Marketing 46(3): 102-107.

- Polson N, Scott J (2011) Shrink globally, act locally: Sparse Bayesian regularization and prediction. JM Bernardo, MJ Bayarri JO Berger, AP Dawid, D Heckerman, et al. (Eds.), Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK.

- Skinner BF (1938) The behavior of organisms. New York, USA.

- Skinner BF (1953) Science and human behavior. New York: MacMillan, USA.

- Stan Development Team (2017) Found under: http://mc-stan.org/users/documentation/.

- Tesla (2015, 2017) Found under: http://www.Tesla.com.

- Thorndike EL (1911) Animal Intelligence: Experimental Studies. Macmillan: New York, USA.

- Train K, McFadden D (1978) The goods-leisure tradeoff and disaggregate work trip mode choice models. Transportation Research 12(5): 349-353.

- Train K, McFadden D, Ben Akiva M (1987) The demand for local telephone service: A fully discrete model of residential calling patterns and service choice. Rand Journal of Economics 18(1): 109-123.

- Train K, McFadden D, Goett A (1987) Consumer attitudes and voluntary rate schedules for public utilities. Review of Economics and Statistics 69(3): 383-391.

- Train K, Ben Akiva K, Atherton T (1989) Consumption patterns and self-selecting tariffs. Review of Economics and Statistics 71(1): 62-73.

- Volkswagen (2015,2016,2017)

- Volvo (2015, 2016, 2017)

- Watson JB, Raynier R (1920) Conditioned emotional reactions. J. exp. Psychol 3(1): 1-14.

- Westing JH, Albaum GS (1975) Modern marketing thought. University of Michigan: Macmillan, UK.

-

Houssam Jedidi and Oliver Heil. WTP for Luxury EVs and their Attributes: A Bayesian Approach to Highlight the Ecology Effect onDM. Sci J Research & Rev. 2(1): 2019. SJRR.MS.ID.000530.

WTP for Luxury EVs, Attributes, Bayesian, Ecology, Luxury electric car buyers, Manufacturers, automobile segment.

-

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.