Research Article

Research Article

Analyzing Justice, Equity, Diversity, and Inclusion Discourses on Athletic Training Program Websites

Brittany A Clason, Ed.D., ATC* and Esra A Hashem Ed.D.

California State University, Fresno

Brittany A Clason, Ed.D., ATC, California State University, Fresno

Received Date: April 09, 2025; Published Date: April 28, 2025

Abstract

Context: The Commission on Accreditation of Athletic Training Education (CAATE) expects athletic training programs to recruit diverse populations, incorporate JEDI into curriculum, implement inclusive and equitable policies, and foster inclusion within the program. This helps increase students’ sense of belonging, thus positively impacting their academic and professional success, and advancing the profession by creating a more diverse demographic. JEDI content on an athletic training website can indicate inclusivity within an environment, impacting students’ decisions to attend an institution.

Objective

Conduct a critical discourse analysis on athletic training program websites, specifically analyzing the content for representation of JEDI discourses.

Design

Qualitative study

Setting

Professional Athletic Training Programs

Participants

Nine institutions from one state/territory in the United States that have professional athletic training programs and offer master’s degrees in athletic training.

Data Collection and Analysis

Researchers reviewed the homepages for each institution’s professional athletic training program. A multimodal analysis was conducted where researchers reviewed, written text as well as visuals, such as photographs and videos. The content of each homepage was analyzed for discursive manifestations of JEDI. Observations, discourses, and general impressions were recorded.

Results

The number of JEDI discourses per university ranged from 4 - 21. Several programs used images that depicted inclusive environments. These images, along with JEDI discourses, created a feeling that all students were welcome, would be included, and would be successful. Some institutions had limited JEDI content and instead emphasized academic rigor, leading to feelings of exclusion and competitiveness.

Conclusions

Incorporating JEDI content onto websites may be an area of growth for athletic training programs. The inclusion of JEDI-specific discourses may help athletic training programs meet the CAATE’s standards regarding diversity, equity, and inclusion, and is therefore important for athletic training programs to consider. Additionally, creating environments of inclusiveness and belonging may help programs recruit and retain more diverse students; leading them to professional and academic success.

Keywords: Athletic Training Education; Student Success; Inclusivity and Belongings

Key Points of Manuscript

1. Professional athletic training programs are required to demonstrate advancement in justice, equity, diversity, and inclusion (JEDI) by recruiting diverse students, faculty, and preceptors; incorporating JEDI in the program curriculum; implementing policies that are inclusive and equitable; and creating an environment of inclusivity.

2. The number of JEDI discourses per university ranged from 4 - 21, with several programs also using images that depicted inclusive environments, creating a feeling that all students were welcome, would be included, and would be successful.

3. Some institutions had limited JEDI content and instead emphasized academic rigor, leading to feelings of exclusion and competitiveness.

4. JEDI content on an athletic training website can indicate inclusivity within an environment, impacting students’ decisions to attend an institution and increase their sense of belonging.

5. The inclusion of JEDI language on athletic training websites may help programs meet the CAATE’s standards, and is therefore important for athletic training programs to consider.

Introduction

The Commission on Accreditation of Athletic Training Education (CAATE) has developed 94 professional standards for professional athletic training programs.1 Some of their recent changes to the standards include two standards on diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI). [1] Specifically, the CAATE requires professional athletic training programs to demonstrate advancement in justice, equity, diversity, and inclusion (JEDI) by recruiting diverse students, faculty, and preceptors; incorporating JEDI in program curriculum; implementing policies that are inclusive and equitable; and creating an environment of inclusivity.[1] Despite the requirement to meet these standards, demographic information in athletic training historically does not show a diverse population.[2-3] Therefore, athletic training educators have been charged with the responsibility to promote social justice; reduce disparities; eliminate discrimination; and advance the profession by recruiting, admitting, and retaining a diverse student population[2].

Creating an equitable learning environment that perpetuates inclusivity and demonstrates diverse perspectives is important because it helps institutions recruit and retain students, increases students’ sense of belonging, and improves measures of academic and professional success.[4-8] Studies have shown that prospective students from marginalized backgrounds are more likely to select institutions to attend that provide opportunities that reduce barriers and increase equity (e.g., financial aid and other scholarship opportunities), and those that foster a sense of belonging.[4- 5] Feelings of interconnectedness and belonging to a group are important factors in the formation of social identity, a variable that has been shown to improve measures of student success.[8-10] Therefore, current students who feel connected to, understood, supported, included, and safe will ultimately perform better in the classroom, be more comfortable seeking help and asking questions, and feel more confident and respected, thus increasing their opportunities for success.[6-10] Marketing and communications materials, such as websites, are powerful tools that may be used to affect people’s thoughts, emotions, and behaviors[11-12].

Literature has shown that websites are the most important platform to help students make decisions about a university[13] and when faced with a decision to choose between two programs or universities, students will choose the one that best represents their social identity.[14] Websites that incorporate equitable and inclusive language and represent minoritized groups may make people who identify with those groups feel included,[15] increasing their sense of belonging and ultimately impacting their decision to attend the university.[4-5] Therefore, the inclusion of JEDI content on an athletic training website may increase marginalized students’ sense of belonging and impact their decision to attend an institution, aiding in program efforts to meet the CAATE standard of recruiting and retaining diverse students.

The purpose of this study was to conduct a critical discourse analysis on athletic training program websites, specifically analyzing the content for representation of JEDI discourses. The inclusion of JEDI content is important on these websites because

1) it may affect an athletic training program’s ability to meet the CAATE DEI standards regarding recruiting and retaining diverse students,

2) it helps promote JEDI in athletic training, advancing the profession, and

3) creating content that is inclusive helps increase sense of belonging, which may have a positive impact on student success.

Methods

This qualitative study utilized critical discourse analysis as its method. Critical discourse analysis is the study of language; it focuses on power in language, and sheds light on discursive aspects of societal disparities and inequalities.[16-17] The method emerged from critical theory, which is focused on challenging ideologies. [18] For critical discourse scholars, text is more than a means of communication; language is action that represents, maintains, or challenges social structure.[19] It is not only about the explicit discourses present, but how they are conveyed and the impact they have on people, particularly from marginalized groups.[20] It is important to note that methods in critical discourse analysis are not homogeneous, resulting in a diversity of approaches aimed at achieving the same objective.[21] While there are several methods for conducting a critical discourse analysis, in this study, the researchers utilized Norman Fairclough’s social discursive approach of critical discourse analysis, which emerged from critical theory.[22]

There are three dimensions and forms of analyses in this model, 1) a textual analysis, 2) a processing analysis, and 3) a social analysis.[22] The textual analysis focuses on vocabulary, word choice, and what was apparent in written and visual discourses. In the processing analysis, researchers must consider the producer and receiver of the discourse as well as the explicit and implicit messages received by the audience by what is both said and not said. Finally, the social analysis interprets what is apparent in the broader sociocultural, political, and ideological context. [23-25] Specific information regarding how the researchers collected and analyzed data in each of these contexts can be found in the data collection and data analysis sections below. Because this study did not include human subjects and only collected information from existing documents, it was considered exempt as defined by the Committee for the Protection of Human Subjects (CPHS) at California State University, Fresno. For transparency, the Standards for Reporting Qualitative Research (SRQR) was used.[26]

Participants

Participants included nine institutions from one state/territory in the United States that have professional athletic training programs and offer master’s degrees in athletic training. These institutions were chosen because

1) The Universities Serve Diverse Student Populations (see Table 1),

2) The State/Territory Offered Samples from Both Private Not-For-Profit and Public Universities, And

3) The Athletic Training Programs Within This State/ Territory Were Already Caate Accredited, Meaning None of the Universities Were Seeking Initial Accreditation at the Time of Data Collection.

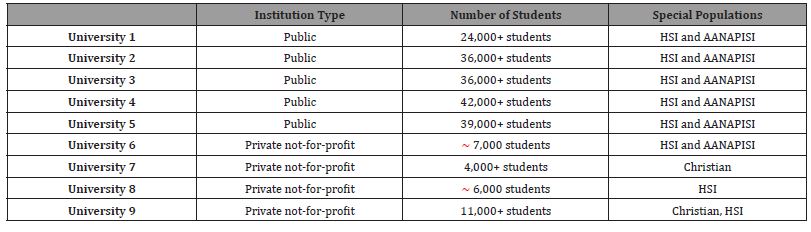

Table 1: University Profiles

These universities were also not from a state/territory that currently has anti-DEI legislation, which may prevent or influence the presence of explicit JEDI content on their webpages. [27] Of the universities that were selected, five (55.6%) were public universities and four (44.4%) were private not-for-profit universities. Additionally, two (22.2%) were in their initial CAATE accreditation while seven (77.8%) were continuing accreditation.

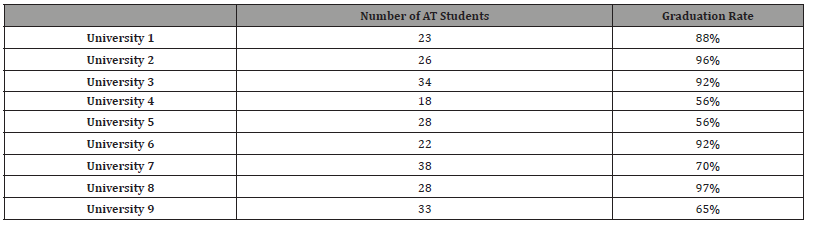

University names have been removed to protect anonymity. However, their university profiles can be found in Table 1. While eight of the nine universities used in this research are Hispanic Serving Institutions (HSI) and/or Asian American and Native American Pacific Islander-Serving Institutions (AANAPISI), it is important to note that during the 2022-2023 academic year, only 6.6% of all athletic training students in the world identified as Hispanic, and only 4.4% identified as Asian.3 Therefore, the programs reviewed in this research may have some of the most diverse student populations in the world. Students enrolled in professional athletic training programs at each of the universities varied, with threeyear aggregates ranging from 18 - 38 students. Graduation and retention rates for each program also varied between universities, with three-year aggregates ranging from 56% - 97% (M = 79%). Three-year aggregate scores for each athletic training program can be found in Table 2.

Table 2: Three-Year Aggregate Information

Data Collection

Program websites were collected using the CAATE Search for an Accredited Program tool28 and data was collected from websites in July and August 2024. Specifically, the two researchers reviewed the homepages for each institution’s professional athletic training program. These program homepages usually included program overviews, mission/vision statements, strategic plans, and admissions information. The researchers did not deviate from the homepages to search for specific programmatic content, or click on each link within that page. For each university in this study, one website (the homepage) was reviewed. The researchers conducted a multimodal analysis, reviewing written text as well as visual modes of communication, such as photographs and videos. The researchers analyzed the content of each homepage for both explicit and implicit discursive manifestations of JEDI. Meaning the researchers not only looked for explicit terminology related to JEDI, such as phrases and terms like “equitable opportunities,” “diversity,” and “inclusion”, but also looked for verbiage that may imply they are fostering a diverse, inclusive environment. For example, mentioning that students would work with a variety of patient populations can be interpreted as creating a diverse environment; therefore, phrases such as these were also counted as manifestations of JEDI discourses. Mentions of financial aid and other scholarship opportunities are also examples of manifestations of JEDI discourses since they imply that the university is taking steps to reduce barriers to education.

Researchers reviewed each university’s program homepage and used a shared spreadsheet to record the number of JEDI discourses (each word, phrase and/or picture were counted and then reported as a number). General impressions, observations, and additional notes that would help with the processing and social analyses were also recorded on the spreadsheet. To ensure consistency and reliability of the analysis, both researchers independently recorded and then compared their results. Differences in results were discussed and duplicates were removed (meaning one word, phrase and/or picture could not count twice). After reviewing all of the program homepages, each of the researchers conducted a second review of the websites to check if there was any further data to include in the analysis. Identifying information used to collect, organize, interpret, and code data during the data collection process were kept confidential and stored on password protected computers in a password protected program. Only the researchers had access to the data collected.

Data Analysis

In accordance with Fairclough’s three-dimensional approach to critical discourse analysis,[22] researchers started first with a textual analysis of each homepage. When conducting the textual analysis, the researchers separated JEDI discourses into two general categories: Justice and equity, and diversity and inclusion. Social justice and equity are akin to verbs; they are commitments to action that rectify existing inequities. [29-31] Therefore, the researchers identified text and/or images that explicitly mentioned or inferred a commitment to social justice or equity, or that emphasized programming to help marginalized groups. For example, mention of financial aid opportunities, flexible application requirements, accommodations for those with disabilities, etc. can be seen as a commitment to social justice as these are tools used to create an equitable learning environment. Key words and phrases such as these were recorded onto the shared spreadsheet in one column.

Diversity, on the other hand, is defined as the inclusion of different races, cultures, or types of people in a group or organization.[32] It is associated with the term’s equality, openness, multiculturalism, welcoming, belonging, and inclusivity. [32] Diversity promotes harmony and awareness between groups. While diversity is certainly an essential prerequisite for social justice, it is defined differently.[33] Thus, when the researchers’ investigated discourses that represented diversity and inclusion, they looked for word choice that emphasized a sense of belonging and welcoming environment (e.g., caring faculty, various settings and patient populations, etc.), or imagery that reflected diverse populations (while acknowledging that diversity is not always visually apparent). These key words and phrases related to diversity and inclusion were recorded onto the shared spreadsheet in a second column, alongside the justice and equity discourses. Results of the textual analysis are presented as

1) the number of discourses for justice and equity,

2) the number of discourses for diversity and inclusion, and

3) the total number of discourses on the program’s homepage.

Descriptions of the imagery were also recorded using a third, separate column. On a fourth column of the spreadsheet, the researchers recorded general impressions, observations, and notes for the processing analysis. This essentially served as the interpretation of the data thus far collected. Next, the researchers compiled this data from the textual and processing analyses into the results narrative. After reviewing both sections, the researchers then reflected on the participant data (the institutional characteristics), the existing research about JEDI as described in the introduction section, and collaboratively produced the narrative for the social analysis section.

Results

Results of the critical discourse analysis were divided into three dimensions, 1) textual, 2) processing, and 3) social based on Norman Fairclough’s social discursive approach of critical discourse analysis.[22]

Textual Analysis

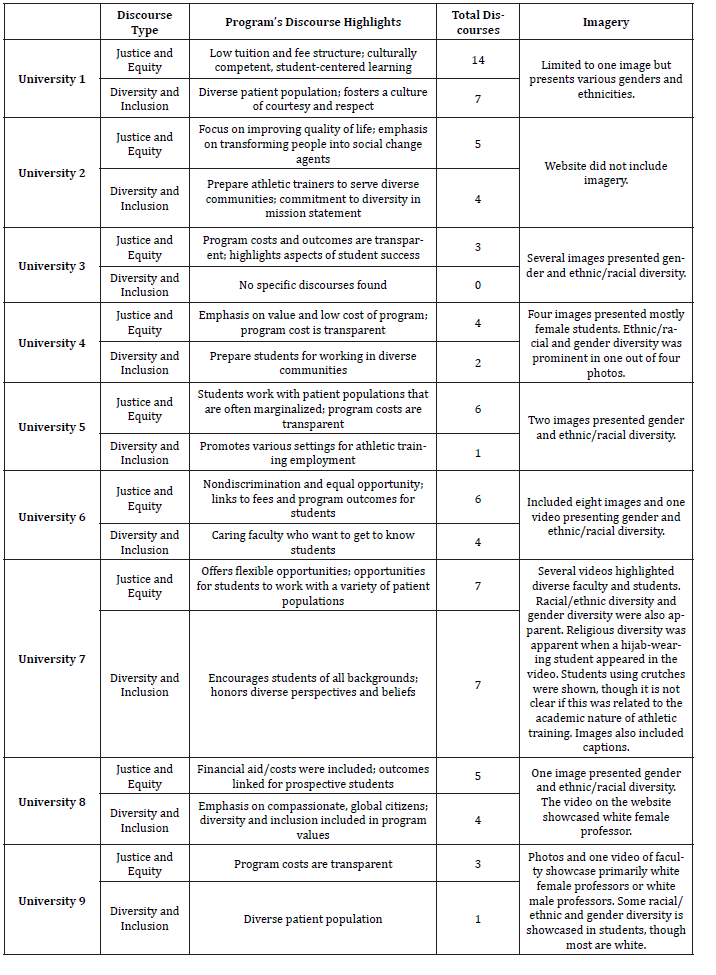

Table 3: Results of Textual Analysis for each University

The textual analysis of this study focused on vocabulary, word choice, modality, genres, and what is present and not present.[24] It also included what is or is not represented in images (in terms of visual demographic characteristics); the researchers acknowledge that often, invisible forms of diversity are not apparent in imagery (sexual orientation, disability, religious diversity, socioeconomic status, etc.).[17] Results of the textual analysis are presented in Table 3.

Processing Analysis

The processing analysis included general impressions and feelings from the website content; this is sometimes referred to as the interpretation.[24] This analysis considers the producers and receivers of the discourses, the voice, and emotions evoked by the discourses. The institution (and its professional athletic training program) is the producer of the discourses in the study, and prospective students are the receivers of the discourses (they are the websites’ main target audience). Results of the processing analysis are presented below.

1. University 1: The website content heavily emphasized JEDI themes. In relation to justice and equity, the institution continuously mentioned programming and opportunities to reduce barriers for different student populations. There were several mentions of financial flexibility, such as low program costs, scholarship opportunities, no-cost immunizations, and optional clothing costs. In addition, the program stated it had multiple application deadlines, that the curriculum was continuously being improved, and that the program allowed students to keep summers off to conduct internships. This gave the researchers the impression that the program was trying to emphasize its accessibility and flexibility for diverse learners, such as low-income students or first-generation students. Diversity and inclusion discourses were also commonplace. Specific discourses, such as mentions of a “diverse patient population,” “rich cultural history,” and a commitment to diversity in the program values reinforced this theme. Discourses on University 1’s website reflected its low-cost, accessibility, and commitment to diversity.

2. University 2: The website content did include general JEDI themes, such as a commitment to transforming graduates into social change agents, a commitment to diversity in the departmental mission, and an emphasis on promoting the welfare and intellectual progress of students. However, compared to other institutions in this study, there was less emphasis on what made the program accessible to marginalized students (e.g. it did not mention low costs, scholarship opportunities, or flexible programming that allows students to work during the summer). Instead, there were mentions of “high-quality” and “rigorous” education. This gave the researchers the impression of academic exclusivity.

3. University 3: Content on this website was extremely limited compared to other program websites; the website consisted mostly of links to content on different websites. In terms of justice and equity discourses, the website included a link to scholarship awards. However, there were no discourses found that emphasized diversity and inclusion, a sense of belonging, or a description of the environment the students would learn in. For prospective students from diverse backgrounds, it was not clear how the program would specifically serve them.

4. University 4: Website content was limited for this program. Diversity was nonetheless highlighted, and a discourse about preparing “students to work in a diverse community” was found. Other discourses such as, “best value” and “low cost for residents” - and the transparent cost of the program - were also found. While this infers it is a program that is accessible to lower-income students, and thus is committed to social justice and equity, the content was limited, and it did not include further explanations of financial aid opportunities, program flexibility, or other opportunities for diverse learners. Therefore, despite these specific discourses to promote JEDI, the researchers’ impression of the website was that it did not fully showcase the program’s inclusive environment to prospective students.

5. University 5: While robust, content on this website utilized less JEDI discourses than other institutions. Website content focused on the program requirements, the need for competency in athletic training education, and the relative competitiveness compared to other athletic training programs. Scholarships and travel grants were listed, showing a commitment to assist students from low-income backgrounds, which the researchers considered a social justice/equity discourse. While the diversity and inclusion discourses were limited on this website, the program did highlight that athletic trainers may work in a variety of settings with diverse patient populations. The researchers’ general impression of the website was that the content focused mostly on the academic standards and the program being competitive -which can be considered exclusionary - as opposed to emphasizing an inclusive and welcoming environment.

6. University 6: Content on this website was robust and lengthy, but discourses were not as specific to JEDI as other institutions. In terms of social justice and equity content, the discourses found included a nondiscrimination and equal opportunity statement, as well as program costs listed. There were limited diversity discourses that were blatant - “diversity” was not listed specifically as a program value and a commitment to diverse students or communities was not seen. Inclusion did appear in discourses, however; a few statements inferred that the institution aimed to foster an inclusive environment for students, by emphasizing that faculty and staff work closely with students and want to “get to know” them. While justice, equity, and diversity discourses were not as blatant on this website as some other institutions, the researchers’ general impression was that the program conveyed it was important to foster an inclusive, welcoming, comfortable environment for all students.

7. University 7: This website appeared to have specific JEDI content but also a pointed commitment to the Christian perspective. In terms of social justice and equity discourses, the website emphasized flexible opportunities and transparency in program costs; yet, the program required summer work, which may be a limiting factor for students who are employed to pay tuition. Diversity and inclusion discourses were seen in statements about “honoring diverse perspectives and beliefs,” encouraging “people of all backgrounds,” and specifically welcoming international students. The institution was the only one that included image captions, which may improve accessibility for those with disabilities. In imagery, like most other institutions, racial, ethnic, and gender diversity was apparent, but also apparent was a form of diversity that is sometimes not apparent in imagery – religion. One image featured what appeared to be a Muslim woman wearing hijab. The specific inclusion of a religious minority on an institutional website that reinforced a commitment to Christian values was notable to the researchers, leaving the general impression that the program aimed to convey it is open to students of all racial, ethnic, and religious backgrounds.

8. University 8: The program website appeared to have limited content; however, their specific use of JEDI discourses was valuable. For example, the website specifically highlighted financial aid opportunities and special rates for military personnel. Diversity in clinical settings was also highlighted. Discourses such as, “compassionate global citizens” and “leaders from diverse backgrounds” promote diversity and inclusion in the program. Additionally, diversity and inclusion were highlighted as program values. The use of JEDI discourses throughout the website left the researchers with a general impression that the university and program were committed to JEDI.

9. University 9:The website had extremely limited JEDI discourses. While the institution did mention students working with diverse patient populations, a specific focus on inclusion on campus or for diverse students was not apparent. Imagery included mostly white faculty and students, though there was gender diversity. Overall, the researchers’ impression of the institution was that it was exclusive; the content of the website emphasized a highly-selective admissions process, year-round course work, and no specific scholarship or aid opportunities were promoted. There was also a strong commitment to the Christian perspective; phrases like a “faith-based environment” and “glorify God” could be found on the website, which may create a feeling of exclusivity for students who are not Christian.

Social Analysis

The social analysis included the researcher’s explanation of the discourses used in each program’s website while considering the broader sociocultural and ideological contexts. In order to do this, the researchers interpreted the data they found during the textual and processing analyses but also considered existing information such as the CAATE requirements, state laws, institutional characteristics and current research about benefits of JEDI. When considering the CAATE’s impact on these institutional websites, the researchers acknowledged that there were several pieces of information that the CAATE requires athletic training programs to post on their websites (e.g., program outcomes, scholarship information, and financial accessibility). Because this information was included on every website, the researchers did not emphasize these discourses in the processing analysis unless they were mentioned extensively (i.e., repeatedly or in great detail) on a particular program’s page. However, these terms were included in the number of discourses for each website.

The researchers also considered state laws and their impact on JEDI content. Some states have introduced or passed bills that ban DEI.27 States like Florida, Texas, and Utah have approved bans on DEI efforts in higher education.[27] It is important to note that the participants in this study were not located in a state that has introduced or passed anti-DEI legislation; thus the researchers concluded that such legislation did not prevent these institutions from posting JEDI content, though there is always a possibility that nationwide trends may influence or minimize such content in any state. In terms of institutional characteristics, as well as the research about the benefits of JEDI, the researchers considered several factors when analyzing the data. One important note that the researchers found was that there was no statistical significance found between university enrollment and graduation rates, and the number of discourses that were found on each website that was reviewed. Thus, JEDI content on websites did not appear to be directly related with enrollment or graduation rates. Nonetheless, the researchers observed that programs that utilized blatant JEDI discourses emphasized a more welcoming environment, while those that did not include JEDI-specific language felt “distant,” self-promotional, and overly competitive. The researchers noted that seeing the inclusion of diverse groups, including religious and racial/ethnic minorities, highlighted the multicultural nature of the campus. These images, along with the JEDI discourses, appeared to aim to emphasize that all students were welcome, would be included, and would be successful at the university.

The researchers also observed the specific ways that some institutions aimed to promote equity; they noticed that universities that highlighted flexible application deadlines, a reduction in financial barriers, and lack of summer courses so students could work or complete paid internships showed a particular commitment to justice and equity (i.e., students could earn money to pay for tuition and books). Since marginalized students often consider financial needs in the institutional selection process, this was particularly important when looking for JEDI content on the websites. [4-5] These curriculum choices may attract students who have particular financial and/or family needs. In opposition, university websites that focused on the competitive rigor of the program and its coursework and highlighted “selective” admission processes appeared to create feelings of exclusion, leaving the impression that only top students in the field would be selected, regardless of any previous extenuating circumstances (e.g., language barriers, financial barriers, disability, etc.) that may have hindered student success outcomes.

While prospective students do make decisions to attend an institution based on its academic reputation, marginalized students also look for content that emphasizes financial opportunities and a sense of belonging.[4] The researchers noted a stark difference between the two private Christian institutions in this study; one made a concerted effort to emphasize its inclusive environment and even featured a religious minority in its website materials. It appeared that the campus aimed to emphasize that all - not just Christians - were welcome and would succeed at the institution. The other university, instead, emphasized the spiritual nature of the campus; it did not emphasize its inclusive nature. While the latter approach may seem exclusionary to those who do not identify with the faith tradition, it is important to acknowledge that both campuses have potential to either decrease or increase students’ sense of belonging. For those who do not identify with the faith tradition, they may feel more welcome at the former campus.

But for those who identify with the faith tradition, community may be found among like-minded individuals, and thus a sense of belonging may increase. Spiritual connectedness is a noted component of increasing sense of belonging among marginalized students,[4] and therefore either campus may have the potential to increase or decrease belongingness, depending on the individual’s background and beliefs. Interestingly, while the 2022-2023 CAATE Analytic Report showed that athletic training graduates are not diverse (75.5% are white),[3] the universities included in this study mostly consisted of HSIs and AANAPISIs, meaning these are likely some of the most diverse athletic training programs in the world. While the general impression of the discourse analysis left the researchers thinking that most universities could improve their sense of belonging by including more JEDI-specific discourses, and/ or discourses that are considered manifestations of JEDI content, on their websites, they may be already recruiting diverse students because of the unique demographic population in their state/ territory.

Discussion

Results of the critical discourse analysis revealed that JEDI content was featured at various levels in athletic training program websites. Some websites included justice and equity discourses, showing that these programs made concerted efforts to highlight opportunities to reduce barriers for marginalized students. Diversity and inclusion discourses were also seen on some program websites, emphasizing the value of diversity and focusing on creating an inclusive, welcoming environment. Other programs had less JEDI content, and instead focused on program requirements, academic rigor, and the overall competitiveness of the program. While a majority of the universities in this study were HSIs and AANAPISIs, the language included on some program websites was not always inclusive, leading researchers to conclude that this may be an area of growth for athletic training programs.

The type of language and imagery used on program websites should be heavily considered, as it may be an important factor in creating a feeling of belonging and inclusivity. JEDI content may include specific terminology such as, “diversity,” “equity,” and “inclusion,” but content may also be implicit. Language that emphasizes the caring nature of faculty or indicates that there is robust support for students are ways institutions can showcase to marginalized students that they belong and can succeed.[8] While emphasizing program successes may be a good marketing tool, studies have shown that when two programs have similar success, the student is more likely to choose the program that meets their social identity concerns [14].

To emphasize an institution’s commitment to equitable access and outcomes, including information regarding financial aid and other scholarship opportunities is important.[4,8] In addition, highlighting opportunities for various learning styles and flexible environments is particularly meaningful for marginalized students of varying abilities or social and economic backgrounds. [8] Programs may also consider emphasizing university-wide programming such as centers and spaces on campus for students of varying identities, student clubs and organizations that emphasize belonging, or institutional resources to support equitable outcomes that help increase students’ sense of belonging and confidence in their success.[8] In imagery, showcasing diversity should be authentic, accurate, and intentional.[34] Showing pictures of students - or faculty and staff who serve as role models for students - of varying cultural or religious backgrounds, abilities, ages, genders, and races can create feelings of inclusion and show the diversity of the campus.[34] Students who see themselves reflected on campus are more likely to feel like they belong there.[8] Content should strike a balance of representing diverse individuals and programming without being inauthentic.[34] Over-representation, or inaccurate representation of the program’s diverse population, should be avoided, as this can lead to feelings of tokenism.[34]

Data collected by the CAATE shows that athletic training programs lack diversity among their student populations,[3]and the CAATE has developed standards to advance JEDI in athletic training programs.[1] Studies have shown that having diversity among students, faculty, and staff allows for more opportunities for social support and mentorship, and improves a sense of belonging through feelings of relatedness.[8], [35] Additionally, as students interact more with those outside of their own demographic, there is improvement in critical thinking and problem-solving, morale, satisfaction, openness and understanding of others, and feelings of support.[35] The development of these feelings and attributes is vital for their success.[4-8], [9-10], [35] Recruiting, admitting, and retaining a diverse student population, and ensuring their success in their athletic training programs, advances the profession of athletic training and creates an opportunity for more equitable healthcare [2].

Because websites and other marketing materials help programs recruit and retain students, [4-5] the language included on the website is particularly important. These marketing efforts influence a student’s perception of the university, and decisions to attend and remain at an institution are linked to this perception. [14,36] For some students, marketing materials are their only source of information when deciding on a college.[36] Thus, for institutions looking to recruit and retain diverse student populations, and increase students’ sense of belonging, language that focuses on equity and emphasizes inclusion can help.[7,14] Improving students’ sense of belonging is important, because it leads to positive outcomes, as sense of belonging is linked with their academic and professional success.[6-8] The inclusion of JEDI language on athletic training websites may help athletic training programs in this recruitment and retention process, thereby meeting the CAATE’s DEI standards.

Limitations

First, the researchers acknowledge their positionality - their differing and intersecting identities, their experiences, and their education that led to the interpretations of the data. The methodological approach was designed to reduce implicit bias in this study. A second limitation was that academic websites are controlled at institutions in differing ways. Accrediting bodies influence web content, as seen in this study. In addition, some institutions have central offices, such as campus-wide marketing and communications departments, which dictate or influence content on websites in order to promote brand-aligned communications; at other institutions, there is a more decentralized model, and individual departments have more control over the content.[37] The researchers did not investigate how content was produced for each institutional website.

Another limitation is that the researchers focused only on content on the institutional program homepages, and did not deviate from the homepage to explore other content on the websites which could have included additional JEDI discourses. This study was also limited in that, as a critical discourse analysis, it included what the researchers observed on the program websites. While existing research showcases the importance of JEDI content and its impact on student decision making and sense of belonging, this study did not include interviews or surveys with students on their perceptions of website content or its impact on their decision making. Future research should be conducted to show potential correlations between student decision-making and feelings of inclusion and belonging.

Declarations

Funding

Private and/or institutional funding was not sought after for this research project.

Conflicts of interest

There are no relevant financial or non-financial interests to disclose.

Ethics approval

This study was reviewed and approved by the Committee on the Protection of Human Subjects (CPHS) prior to the start of data collection.

Consent

Because this study does not include human subjects and only collects information from existing documents, it is considered exempt as defined by CPHS at California State University, Fresno and does not require consent to participate.

Author Contributions

1. Brittany A. Clason: Conceptualization, literature review, data curation and analysis, writing of original draft, review and editing of subsequent drafts.

2. Esra A. Hashem: Conceptualization, literature review, data curation and analysis, writing of original draft, review and editing of subsequent drafts.

References

- (2024) Commission on Accreditation of Athletic Training Education. Standards and procedures for accreditation of professional programs in athletic training.

- Adams WM, Terranova AB, Belval LN (2021) Addressing diversity, equity, and inclusion in athletic training: Shifting the focus to athletic training education. J Atul Train 56(2): 129-133.

- (2024) Commission on Accreditation of Athletic Training Education. 2022-2023 CAATE analytic report.

- Howard Hamilton MF (2009) Standing on the outside looking in: Underrepresented students’ experiences in advanced-degree programs. Stylus.

- Jordaan Y, Weise M (2010) The role of ethnicity in the higher education institution selection process. S Afr J High Educ. 24(4): 538-554.

- Gerstl Pepin C, Aiken JA (2012) Social justice leadership for a global world. Information Age Publishing.

- Shafritz JM, Ott JS, Jang YS (2015) Classics of Organizational Theory (8th edition). Cengage Learning.

- Nunn, LM (2021) College Belonging: How First Year and First-Generation Students Navigate Campus Life. Rutgers University Press.

- Hernandez PR, Bloohart B, Barnes RT (2017) Promoting professional identity, motivation, and persistence: Benefits of an informal mentoring program for female undergraduate students. PloS ONE. 12(11): e0187531.

- Clason BA, Yukhymenko Lescroart MA, Sailor SR, Wandeler C (2023) The relationship between psychosocial factors and student success in athletic training students. Athl Train Educ J. 18(4): 163-173.

- Medoff N, Kaye B (2017) Electronic media: Then, now and later (3rd). Routledge.

- Poepsel M (2018) Media, society, culture and you. Rebus Community.

- (2024) Education Advisory Board. Recruiting the digital native: Actionable insights from our 2019 student communication preferences survey.

- Ihme T, Sonneberg K, Barbarino ML, Fisseler B, Sturmer S (2016) How university websites’ emphasis on age diversity influences prospective students’ perception of person-organization fit and student recruitment. Res High Educ 57(8): 1010-1030.

- Nadal KL (2017) Columbia University. Giving psychology away: How to use social media and mainstream media to advocate for social justice. Lecture presented at the 33rd Annual Winter Roundtable on Cultural Psychology and Education; New York, NY.

- Gee JP (2014) How to do discourse analysis (2nd). Routledge.

- Wodak R, Meyer M (2016) Methods of critical discourse studies (3rd). SAGE Publications.

- Glesne C (2021) Becoming qualitative researchers: An introduction (5th). Pearson.

- Fairclough N (2010) Critical discourse analysis: The critical study of language (2nd). Routledge.

- Wodak R, Chilton P (2005) A new agenda in (critical) discourse analysis: Theory, methodology, and interdisciplinarity (1st ed). John Benjamins Publishing Company, Vol.13.

- Given LM (2008) The SAGE encyclopedia of qualitative research methods. SAGE Publications, Inc.

- Chouliaraki L, Fairclough N (1999) Discourse in late modernity: Rethinking critical. discourse analysis. Edinburgh University Press.

- Everett KD (2015) Textual silences and the (re)presentation of black undergraduate women in higher education journals: A critical discourse analysis. [Doctoral dissertation]. Ames, IA: Iowa State University.

- Janks H (1997) Critical discourse analysis as a research tool. Discourse: Stud Cult Pol Educ 18(3): 329-342.

- Sudajit apa M (2017) Critical discourse analysis of discursive reproduction of identities in the Thai undergraduates’ home for children with disabilities website project: Critical analysis of lexical selection. Adv Lang Lit Stud 8(5): 1-28.

- O’Brien BC, Harris IB, Beckman TJ, Reed DA, Cook DA (2014) Standards for reporting qualitative research: A synthesis of recommendations. Acad Med 89(9): 1245-1251.

- Adams C, Chiwaya N (2024) Map: See which states have introduced or passed anti-DEI bills. NBC News.

- Commission on Accreditation of Athletic Training Education. CAATE Search for an Accredited Program Tool.

- Ahmed S (2007) The language of diversity. Ethnic and Racial Studies 30(2): 235-56.

- Gorski PC, Anderson M, Hackman H, Lonnquist P, Naserdeen D (2006) Beyond propaganda: Resources from Arab film distribution. Multicult Educ 13(3): 56.

- Jubas K, White M (2017) Marketing equity: Diversity as keyword for internationally engaged postsecondary institutions. Rev Educ, Pedagog, and Cult Stud 39(4): 349-366.

- Merriam Webster (2024) Diversity.

- Stewart DL (2017) Language of appeasement. Inside Higher Education.

- (2024) University & College Designers Association. Best practices for inclusive and diverse photography in higher education

- Smith DG, Schonfeld NB (2000) The benefits of diversity: What the research tells us. About Campus. 5(5):16-23.

- Rutter R, Lettice F, Nadeau J (2017) Brand personality in higher education: Anthropomorphized university marketing communications. J of Market High Educ 27(1): 19-39.

- Paradise A (2024) Findings from the 2015 CASE educational communications and marketing trends survey [White paper].

-

Brittany A Clason, Ed.D., ATC* and Esra A Hashem Ed.D. Analyzing Justice, Equity, Diversity, and Inclusion Discourses on Athletic Training Program Websites. Sci J Research & Rev. 4(3): 2025. SJRR.MS.ID.000590.

Athletic Training Education; Student Success; Inclusivity and Belonging

-

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.