Mini Review

Mini Review

Research and Development Tax Credit Case Study

James Meersman*

Assistant Professor of Accounting, Department of Accounting, Business, and Economics, Juniata College, Huntingdon, USA

Assistant Professor of Accounting, Department of Accounting, Business, and Economics, Juniata College, Huntingdon, USA

Received Date: October 10, 2021; Published Date: July 21, 2022

Abstract

This paper analyzes previous research conducted regarding enhanced student learning through the use of case study materials. These materials are then further tested by implementing a case study related corporate taxation that was based off of a real world issue and designed to enhance student learning. The case study was implemented both in and outside the classroom, with various modifications resulting from student input and instructor reflection. Any appropriate changes to the case study were then implemented for further instructor observation. The case study was designed to be used in an upper-level accounting taxation course with enough students to work in groups of 3-5.

Introduction

Corporate Taxation classes are typically only taken by those desiring to attain an accounting degree. However, there are many accounting students who have no interest in tax, and those that do are usually seeking opportunities to experience what work will be like after they graduate. While students can understandably look to various tax forms for the technical knowledge required to succeed at an entry level accounting job, many students do not get any exposure to tax consulting as a result of their university studies. Though many collegiate case-competitions exist that try to give students this type of experience, these offerings have time constraints that cause them to be limited in scope. Case competitions also tend to simulate problem solving from a conceptual perspective alone, rather than taking the conceptual and putting it into practice. This case was designed to address and improve upon those issues. That being said, teaching students the skills necessary for the critical thinking in a consulting environment can be very difficult within the walls of a classroom alone. Because of this, the case was also implemented with the expectation that it would be completed both in and outside of class. This paper will discuss a case study developed to enhance student learning in addition to equipping them with the skills needed to solve problems directly related to issues they would face in a tax consulting environment. Before this analysis, a review of effective case study implementation and learning is appropriate in order to contextualize the value of using case studies in the classroom.

Case Study Learning Model

Learning would appear to not come not from the effectiveness of the material presented by the instructor, but solely by what the student does or thinks [1]. Before one can hope to enhance learning, breaking down exactly what learning is must be done first. For the purposes of this paper, a holistic, summarized definition from How Learning Works will be used. Learning can broadly be defined as a process of experiences that ultimately lead to change within the student [1]. This definition can make it difficult to achieve student learning based on traditional teaching methods alone. However, using case studies can be an effective supplement to traditional methods in order to drive learning development. While many students often question the applicability of particular subjects or concepts to their life after college, case studies implement active learning that can directly tie solving specific, real world problems through active learning and critical thinking. How Learning Works advocates the usefulness of case studies in this way: “Analyzing a real-world event provides students with a context for understanding theories and their applicability to current situations.” Having students solve real world problems in order to develop critical thinking skills will enable them to use those skills to address future issues they will face after they graduate.

Bridging the gap between theoretical concepts to practical application of those concepts has always been a barrier for instructors, and tying that practical application to skills needed to vocationally succeed after college can also be challenging. There are three key aspects of case study implementation that allow them to act as this bridge: Foundations, Flow, and Feedback [2]. These three factors were used as a conceptual framework by which the case study was implemented.

Foundations, Flow, and Feedback

While the cases used in a given course are vital to the learning of the students, it cannot be understated how important the preparation is before the first day of class. Though each instructor prepares in various ways, one consistent measure of a successful case study implementation is preparation. This importance can be emphasized by the relevancy of the case study chosen or designed. As important as the implementation of a case study is, the success of a case study is highly dependent on the pedagogy of the instructor throughout the course, not just at the outset [4] Because of this, the flow of the case study throughout the semester is also critical to student learning outcomes, as each class will bring with it various new issues and personalities. An instructor’s ability to address current problems with students and student groups plays a major role in the successful completion of those students in relation to the case. Because no case study is perfect, one must be able to adjust specific aspects of the project throughout the semester. This ties in to the third aspect of case study implementation, feedback. Although getting post-semester feedback can be extremely beneficial, as the students have already received their grade, one must also pursue constant and constructive feedback throughout the process of students completing the case study. Which aspects of the case seem to be more beneficial than others? How does the workload compare to the time constraints given in class? How does the number of team members impact the level of participation in each group? These are a few examples of ways to get open and honest feedback throughout the duration of the case [2].

Influencing Factors

When implementing case studies, there are numerous factors

that need to be considered that can alter your case from one

semester to the next. As stated before, each class bring with it

varying unique features. Some of those feature that have to be

accounted for are the following:

Class Size

I. Course: Core vs. Elective

II. Part Time vs Full Time

III. Gender

IV. Weekly vs. Modular Courses

V. Domestics vs. International Students

VI. Single vs. Multi-section Classes

VII. Executive vs. Graduate vs. Undergraduate

VIII. On campus vs. Online Students

While there are many more factors that can change the delivery and ultimate outcome of one’s case study, the factors listed above serve as a brief list of considerations that need to be taken into account at all three stages of case study implementation [2].

Collaborative Learning

One of the basic components of case studies is collaboration. It is one of the main differences between lecturing and group work, and it encourages vulnerability among students in order to achieve a common goal. Many research studies have pointed to collaborative learning being an effective tool for instruction (Barkley, Major, and Cross, 2014). An extremely important culmination of research related to collegiate learning, Seven Principles for Good Practice in Undergraduate Education outlines various learning principles that were found to be of most use in the college classroom. Of those seven principles, three of them lay the foundation for collaborative learning: encouraging student-faculty contact, encourage cooperation among students, and encourage active learning [5].

Case Study Example

One case study was implemented in an upper level corporate

taxation accounting course in an attempt to enhance student

learning. This case was adapted from research and development

tax credit study previously done by a Big Four accounting firm. The

case in question required the students to complete the following

tasks:

I. Research the tax law associated with the R&D tax credit,

the client, and industry associated with the case.

II. Meet with and formulate list of questions for client (i.e.

the instructor), including a list of required documentation.

III. Develop positions for and document certain company

activities and how they relate to the R&D tax law.

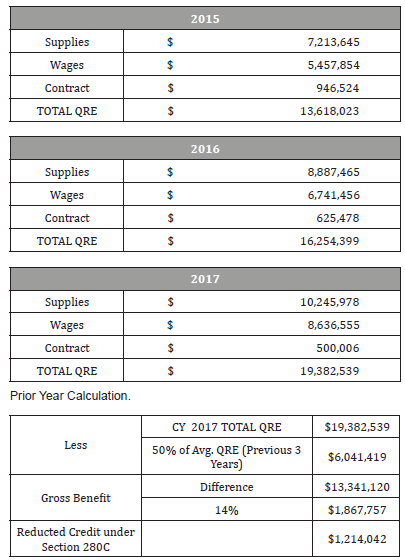

IV. Formulate a tax credit Excel workbook, summarizing the

tax credit.

V. Complete appropriate tax form related to the tax credit.

VI. Write a memo outlining the R&D tax credit, various tasks

completed, and their stance regarding each of the company’s

potential R&D activities.

VII. Perform these actions in a similar hierarchy as an

accounting firm. some students are associates/seniors, some

are seniors/managers, etc.).

VIII. Regularly maintain contact with both the client and the

accounting firm’s partner (both being played by the instructor).

Analysis of Examples

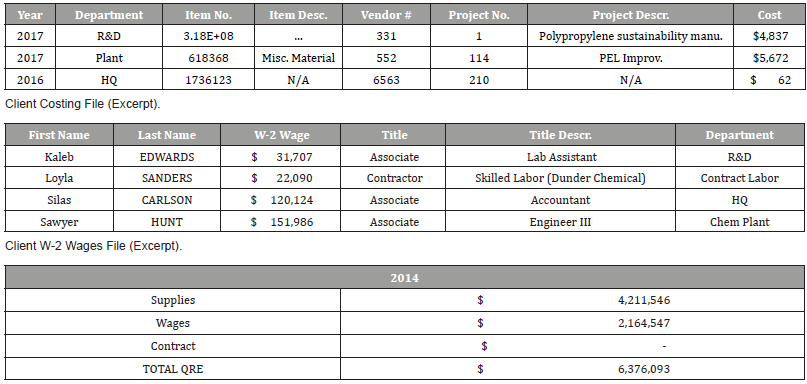

Based on the case study learning model, the case study was analyzed regarding each stage of implementation. Details surrounding the case study can be found in Appendix A.

The foundations

The students were initially given an outline of the R&D tax credit in the form of a PowerPoint slide deck. The slides were loosely based off of presentations given to potential clients at an accounting firm. The slide deck outlined what the credit was, how it was calculated, what data would be needed, and what documentation was required as a result. In addition to this the students were also given a profile of the client to assist them in their initial research. The students were also given a ‘cheat sheet’ of the R&D tax credit to assist them when meeting with the client for documentation purposes or data requests. Lastly, the students were given an Excel document from last year’s credit calculation to use a template if needed.

The flow

While the Foundations’ resources were given to the students early on in the semester, there were various other documents that were needed in order to complete the tax credit. These documents were either going to be created by the teams themselves the final memo), or they would need to ask the client for them (e.g., wages and other costing data). While not every team knew exactly what to ask for initially, the instructor was able to hop in and out of their role as both the client and the accounting firm’s partner in order to assist teams that were having trouble.

Because this particular class was made up of students across several ages, different students were able to take on the various roles of employees of an accounting firm. For instance, a senior would act as a tax manager and review the work of a college junior who was acting as the associate. The roles of the students would merge at times as well, giving students opportunities to fulfill various roles of an accountant in public accounting.

The feedback

The feedback from the case study brought with it mixed results. Students seemed to enjoy the ability to complete a project that had real world implications. They also enjoyed the critical thinking required to find ways to apply the tax law to potentially save their client more money. There were some more constructive takeaways, however. Students found it increasingly difficult to meet as often as needed to complete the assignments. Trying to find the right questions to ask the client also proved to be a source of frustration. Lastly, the unstructured approach taken with the project was a source of anxiety for many students. Not knowing which step to follow, or even what the steps were took a toll on several of the students.

This feedback led to several conclusions. One, most of the constructive feedback was consistent with other classes that implement them. Scheduling conflicts, lack of underlying knowledge, and lack of structured frameworks are consistently found to be complaints of classes that implement these learning strategies. Two, many of these complaints were also consistent with what one experiences at their first entry level job, which can usually lead to a tremendous amount of learning and development of critical thinking. Three, designating more class time to discuss the tax credit itself and how it relates to the course, the project, and the students’ career aspirations would be more beneficial than a truly unstructured approach. This would reinforce the value of the project to the students and give them justification for the amount of busy work required to complete the case.

Several changes resulted from implementing this case study. Allowing more class time for inter-group discussion and questions throughout the semester has been a major change. Giving students designated time at the beginning of class has also proven to be a fruitful way to engage the students before getting into new material. Additionally, occasional status checks and allowing time for inter-team questions has also increased student engagement in the classroom as well. The faculty also observed that requiring peer review at the end of the project helped bolster group participation. Additionally, the faculty saw more student engagement when designating time in class specifically to discuss certain unstructured aspects of the project. This helped bring more clarity and collaboration across teams and teammates.

Observations of Student Learning

Based on the case study learning model, the case study was reflected on regarding each stage of feedback. These observation methods included instructor observation during discussions with different teams, team members, and cross-team activities both in and out of the classroom. Learning was also assessed by analyzing project status at certain periods of time throughout the semester, reviewing work done prior to final submission, and grading final case study submission.

The foundations

Students were not used to the unstructured nature of the case study. Knowing who their teammates were and that there were files for them to analyze resulted in a great deal of discomfort for the students who were used to being told what to do for most of their academic career. Because the case has multiple files in various formats, the case (as simple as it was) was initially intimidating to accounting students.

The flow

R&D tax credit studies make up the majority of tax consulting work related to Big Four accounting firms. These studies analyze the R&D activity of a company and make judgements as to whether or not that activity qualifies as a research expense. To the extent that the activity does qualify, it needs to be quantified by a method well documented in the event of an IRS audit. The quantitative aspects of the case did not seem to overwhelm the students as much as the qualitative requirements. Having to apply tax law to the operations of a company forces an accountant to think like a lawyer or an engineer. This took some time to get used to for many of the students, and it accurately reflects the experiences of many tax associates in tax consulting.

The feedback

As state previously above, the feedback from this case was generally positive. The constructive comments were either addressed by the faculty or empathized with by other classes that also implement case studies. The positive feedback was comforting as most of it related to the useful nature of the case. Students were forced to think differently, independently, and in collaboration with their teammates. This was consistent with the feedback both throughout the semester (before getting their grade) and after the semester

Additional Observations of Collaboration

The case study activities previously listed can also be directly correlated with the three principles outlined for the foundation of collaborative learning:

Encourage student – faculty contact

unstructured nature of the case study required students to interact with the faculty, as the instructor was playing multiple roles and could answer help each team in multiple ways. This encouraged student contact, as the faculty member was the source of both the problems and the solutions throughout the case.

Encourage cooperation among students

Student cooperation was critical to the success of each team, as the workload would have been too much for just one or two students. Being able to delegate and sacrifice at different times throughout the semester was important to build organizational commitment within each team, and each team grew more cooperative throughout the semester.

Encourage active learning

lack of direction given during the beginning stages of the case study was a key factor in encouraging active learning with the students. Not knowing where to start forced the students to research the initial case for themselves before formulating specific questions about the case, rather than open ended one (e.g. what does this data file entail? vs. what should I be doing?).

Future case studies regarding this topic should include a formal assessment after final submission of the case study in order to assess individual learning. Based on the observations listed above, using case studies for corporate taxation is able to be used as a supplement to increase the development of student learning ().

Additional Materials

(Tables here)

Table 1:

Table 2:

Acknowledgement

None.

Conflict of Interest

No conflict of interest.

References

- Ambrose Bridges SA, Di Pietro MW, Lovett M MC, Norman MK (2010) How Learning Works: Seven Research-Based Principles for Smart Teaching. San Francisco Jossey-Bass.

- Anderson E, Schiano B (2014) Teaching with Cases: A Practical Guide. Boston, Harvard Business Review Press.

- Barkley EF, Major CH, Cross KP (2014) Collaborative Learning Techniques: A Handbook for College Faculty San Francisco Jossey-Bass.

- Campoy Renee W (2005) Case Study Analysis in the Classroom: Becoming a Reflective Teacher London Sage Publications.

- Chickering AW, Gamzon ZF (1987) Seven Principles for Good Practice in Undergraduate Education. American Association for Higher Education Buletin, Pp: 3-7.

-

James Meersman*. Research and Development Tax Credit Case Study. Sci J Research & Rev. 3(2): 2022. SJRR.MS.ID.000560

Tax Credit, Foundations, Flow, Feedback, Cheat sheet, R&D tax credit

-

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.