Research Article

Research Article

How do Behavioural, Financial and Technological Interventions Compare in the Public’s Mind when it comes to Health and Sustainability?

Magda Osman1,2 and Sarah C Jenkins2*

1Judge Business School, University of Cambridge, Trumpington St, Cambridge, UK

2Centre for Decision Research, Leeds Business School, University of Leeds, Leeds, West Yorkshire, UK

Sarah C Jenkins, Centre for Decision Research, Leeds Business School, University of Leeds, Leeds, West Yorkshire,

Received Date:August 22, 2024; Published Date:September 16, 2024

Abstract

Currently, we do not know people’s appraisals of, and willingness to adopt behavioural interventions (labelling, public campaigns) when they are pitted against information technological innovations (e.g., recommender systems, autonomous shopping systems) and financial (dis)incentives (e.g. taxes, subsidies). Using the context of sustainable and healthy food consumption, the current survey (n = 398) helps to reduce this evidential gap. In this study participants were presented with three categories of interventions (behavioural, financial, technological); three of each employed to increase healthy food choices, and three of each designed to increase sustainable food choices. Participants were asked to rank interventions according to: 1) their effectiveness in eliciting behaviour change, and 2) their ethicality. Overall, financial interventions were ranked most effective in achieving behavioural change, and behavioural interventions were judged as most ethical. Individual motivations consistently influenced appraisals; gender and income predicted efficacy judgements for financial interventions. Our findings show that there appears to be no overarching “winner” when interventions are judged against different properties. Clearly the public can (and likely do) consider interventions from a variety of dimensions. From a policy-making perspective on communication strategies to promote different types of interventions, their persuasiveness might be improved by taking account of the different dimensions the public value them by.

Keywords:Taxes; subsidies; recommender systems; regressive policy; autonomy; public attitudes

Introduction

When considering which new policy to implement so as to improve healthier and sustainable food choices, policy makers have a range of possible interventions to choose from [1-6]. Interventions can be of a soft kind, such as those that utilise behavioural change methods (e.g., labelling, public campaigns), the hard kind (e.g. taxes, subsidies), and more recently technological types (e.g., smart phone recommender systems). To inform the process of policy decision-making with reference to empirical evidence [7-9] there are several research questions that can be informative in deciding which to implement. The first, most obvious, question evidence can address is: when making direct comparisons between different interventions, which is most effective in supporting reliable behavioural change? Another question that can be addressed is: when examining public’s attitudes towards the different interventions, which is appraised as most favourable? The latter of the two is under researched, and thus forms the focus of the present study.

In fact, there are situations in public policy making where the evidence for the proposed intervention may well be robust in indicating its success, but where public appetite for it is low. The effects of this can lead to limited uptake of the policy [10] or worse still, backfiring effects where the policy leads to a worse outcome than had it not been introduced [11-13]. For example, in the UK, the ‘Switch the Fish’ campaign, was designed to steer consumers away from the consumption of seafood that has been overfished (e.g., Cod, Prawns) towards less commonly consumed sustainable types of seafood (e.g., Coley, Pollock). As well as raising awareness of sustainability issues, collaborative efforts with businesses were made to showcase new meal options that incorporated the less common seafood alternative. Thus, the campaign served two purposes, first providing a rationale for the need to change consumer choices, and second, how to implement those choices in simple, practical ways. However, during and shortly after the period of the campaign there was no demonstrable impact on reducing consumption rates of the most popular seafood items [14,15]. If anything, the findings indicated a backfiring effect. That is, more of the overfished seafood was consumed in the presence of the intervention. Examples of this kind may be rare, but their occurrence is nonetheless significant such that greater efforts are needed to pre-empt this from happening.

The implications here are that public perceptions and attitudes can override well-intentioned food policies. Even if a trialled policy shows evidence of successful behavioural change, it may fail in practice because of muted interest by the recipients of it. The reasons why situations like this occur are varied. In the main, work suggests a complex map of cultural [16,17], sociological [18,19] and psychological factors [20-22] that inform the way in which people make their day-to-day food choices. In an ideal situation, to give a policy the best chance of achieving its objectives, when compared against other possible alternatives, there needs to be good evidence for an intervention’s relative success, and favourable public attitudes towards it relative to the alternatives being considered. However, this exposes a further issue that needs to be considered – the critical dimensions on which favourable attitudes towards an intervention are formed. In the study of public attitudes towards interventions designed to increase the consumption of healthier foods (or at least reduce consumption of foods with high energy content), the findings suggests that they are multi-dimensional [23]. Overall, public support for interventions designed to achieve better health outcomes from food consumption is high [24,25]. For interventions aimed at improving information (e.g., labelling, campaigns) support appeared to be highest compared to taxation schemes. But there are mixed findings regarding the introduction of levies incurred by food businesses for food products with high fat, sugar, or salt content [26-29]. Some research suggests that they are viewed negatively because they are considered regressive [30]. But, also, when the interventions are presented as policies that set targets for food businesses for levels of fat, sugar, or salt in packaged foods, these are viewed more favourable by the public compared to fat, sugar, and salt taxes [26,27,31]. Taken together, the mixed evidence regarding public attitudes toward different types of interventions (i.e., hard types, soft types) might be better understood from the view that what is favourable depends on the dimension on which the interventions are appraised, recognising the fact that appraisals are indeed multidimensional. The critical point then is to pinpoint which dimensions to focus on so as to understand which interventions the public would find favourable.

In the main, there are general patterns that appear across different research samples and methods regarding the public’s views of policies designed to increase healthy food consumption. The most consistent of which is a preference towards policies that are perceived to be autonomy preserving over those that are regressive, because they threaten autonomy. This aligns well with the ‘Ladder of Interventions’ [93], a framework setting out a way to assess different types of policy interventions according to the ethical issues attached to them. As interventions become more intrusive with respect to the threats to personal or communal autonomy, the greater the effort needed to justify the value of their overall public good. Therefore, from previous public attitude research, one salient and consistent dimension used to assess food policies directed towards improving health is ethicality. The present study incorporates this dimension to examine interventions designed to increase consumption of healthier foods (a common focus in this research domain), but also more sustainable foods.

Research reveals generally favourable attitudes towards policy interventions aimed at increasing sustainable food consumption, based on surveys and in-depth interviews [32-37]. However, drawing direct comparisons between different types of interventions attempting to achieve sustainable consumption is harder to find in current literature. One reason is that the range of interventions referred to varies considerably across research, making it difficult to develop an overall profile of which type of intervention is judged as ‘best’. The types of interventions include labelling schemes [38], such as carbon footprints or traffic light labelling, which indicates the levels of greenhouse gas emissions produced during a food products’ lifecycle, measured in tons of carbon dioxide equivalent (tCO2e) (CarbonTrust, 2008). In addition, there are pricing schemes such as levies, as well as distributive pricing schemes where a combination of taxes on high carbon emission food products is used to reduce prices of lower carbon emission foods [39,40]. There are also legislative measures such as laws that impose rulings on mandated levels of carbon dioxide emissions during the food production process, where the food manufacturer and retails directly incur costs regarding the food production and distribution methods if they exceed mandated levels [41-43].

To the extent that consistent patterns in public attitude work on policy making in support of sustainable food consumption can be identified (given the difficulties in drawing comparisons across studies) there are some promising indicators. As with interventions designed to improve healthy eating, regressive policies that are viewed as threats to autonomy (e.g., taxes, bans) are perceived as less favourable than policies that increase awareness (labelling, campaigns) [39,44]. But, like autonomy preserving interventions associated with healthy eating, the public showed concerns of the effectiveness in shifting behaviour towards sustainable consumption such as labelling (e.g., carbon footprints, carbon traffic light labels) because they were viewed as too complex, confusing, or hard to interpret [35,45]. This points to a second dimension on which public attitudes toward differing food policies matters - that is, the efficacy of the policy in achieving what is intended. There is already considerable work on public attitudes concerning their estimates of the efficacy of public policies using behavioural change interventions in a range of policy domains (e.g., exercise, healthy eating, investments) which suggest that acceptability of interventions is strongly predicted by perceived efficacy of the interventions [46-49].

Present Study

To return to the issue highlighted at the beginning, public policy making is not only informed by evidence regarding the efficacy of different types of interventions when directly compared, but also public perceptions of those same interventions. In fact, there are cases where there is misalignment such that, even if there is strong evidence of the efficacy, it can still fail, because public attitudes of the intervention are unfavourable. Of the work that has been conducted, it appears that public attitudes towards interventions designed to increase healthy food consumption or sustainable consumption vary, but it is not clear whether the variance is because the interventions are judged as ineffective, or unethical, or both. Given this, there are three outstanding issues that the present study seeks to address: 1) Emerging technological developments (decision-support systems); 2) Direct comparisons by policy domain (health, sustainability); 3) Direct comparisons of different categories of interventions.

Emerging Technological Developments

Emerging information technologies that build on machine learning into decision-support systems are likely to have a significant impact on the way consumers make their food choices [50,51]. In addition, these decision-support tools, while early in development, will be adopted in bricks and mortar food business establishments and as well as their online versions [52-57]. Given approximately 35% of grocery shopping is now carried out online [58], this offers a greater opportunity for incorporating decision-support tools that can create efficiencies in frequently made, and highly repetitive consumer choices, such as grocery shopping. The two types of decision-support tool carry different implications with respect to efficiencies and autonomy [59]. The first type, an assisted decision-support system, operates on smart phones or laptops, offering recommendations for food items to include in a shopping list [60]. The system uses a combination of retailer promotional offers and machine learning algorithms to tailor recommend promotional offers, as well as options such as nutritional or sustainable foods. The second type is an automated assisted decision-support system, also integrated into smart phone or laptops. It fully automates a shopping list where the consumer defers the choices to the system itself. The system then autonomously makes choices after consumers enter their budget and preferences, handling selections and payment through the system. To date, there has been limited empirical investigation around public attitudes towards decision-support systems of these types [61], either applied to grocery shopping or when compared to more common categories of interventions supporting public policy (e.g., behavioural, financial). Therefore, to address this, the present study draws from examples described in the literature to enable the public to appraise these new types of interventions evolved from technological advances.

Direct Comparisons by Policy Domain

To date, there has been little investigation of how the public appraise the types of interventions included in the present study and whether these differ by policy domain (health, sustainability). To facilitate direct comparisons, and to achieve this systematically, nine different interventions were included (across three overall categories). These interventions referred to three specific types that were behavioural (labelling, public campaigns, communitybased social event) [4,62], three which were financial (tax, redistributing pricing [tax + subsidy], voucher) [4] and three which were technological - ‘smart’ mobile phone application (automated choice, recommended choice, information provision) [61]. Participants had the opportunity to appraise the interventions with respect to two policy domains [2,4,39,44,62-65]: targeting health outcomes by increasing healthy food consumption, and separately with respect to targeting environmental outcomes so as to increase sustainable consumption. In this way, the nine different interventions could be compared according to adoption, and the reasons for adoption in both health and sustainability policy areas according to the dimensions ethicality and efficacy.

Direct Comparisons of Different Types of Interventions

To inform a clearer understanding of public attitudes towards different types of potential policy interventions, what is needed is direct comparison of those interventions. The nine interventions varied by how autonomy threatening they were. The behavioural interventions were the most choice preserving, and financial interventions were the least choice preserving (as typically construed by the Nuffield Ladder, and previous research). The three types of technological interventions could be differentiated in terms of autonomy threatening, where an automatic choice on behalf of a consumer is more threatening than one which recommends a choice or one which simply provides relevant information. From this, the present study provides participants an opportunity to rank order the different types of interventions based on which they would be willing to adopt. Their most favoured top ranked option is then judged according to ethicality and efficacy. The advantage here is that the preferred options are judged according to two different dimensions, but those dimensions are consistently presented within the same survey design. This enables us to determine what intervention is preferred, and what informed that preference according to two properties which are known (from previous work) to predict acceptance of policy interventions. From the work examining public attitudes to policy interventions, we hypothesise that autonomy preserving interventions (e.g., labelling, campaigns) will be judged as more ethical than autonomy threating interventions (e.g., automatic decision-support tool, taxes). Here, we are silent with respect to whether there should be any difference in the pattern or magnitude of ethicality judgments by policy domain (health, sustainability). We also hypothesise that autonomy threatening interventions will be judged as more efficacious than autonomy preserving interventions, again with no a priori assumptions regarding differences in patterns or magnitude of effect by policy domain. We speculate that adoption of an intervention while informed both by dimensions of ethicality and efficacy of behaviour change, judged efficacy will be more predictive of adoption choices than ethicality. Finally, we collect demographic details and pro-environmental attitudes, taking an exploratory approach to examine which individual and group level characteristics influence which interventions are most favourable in the public’s view.

Method

Participants

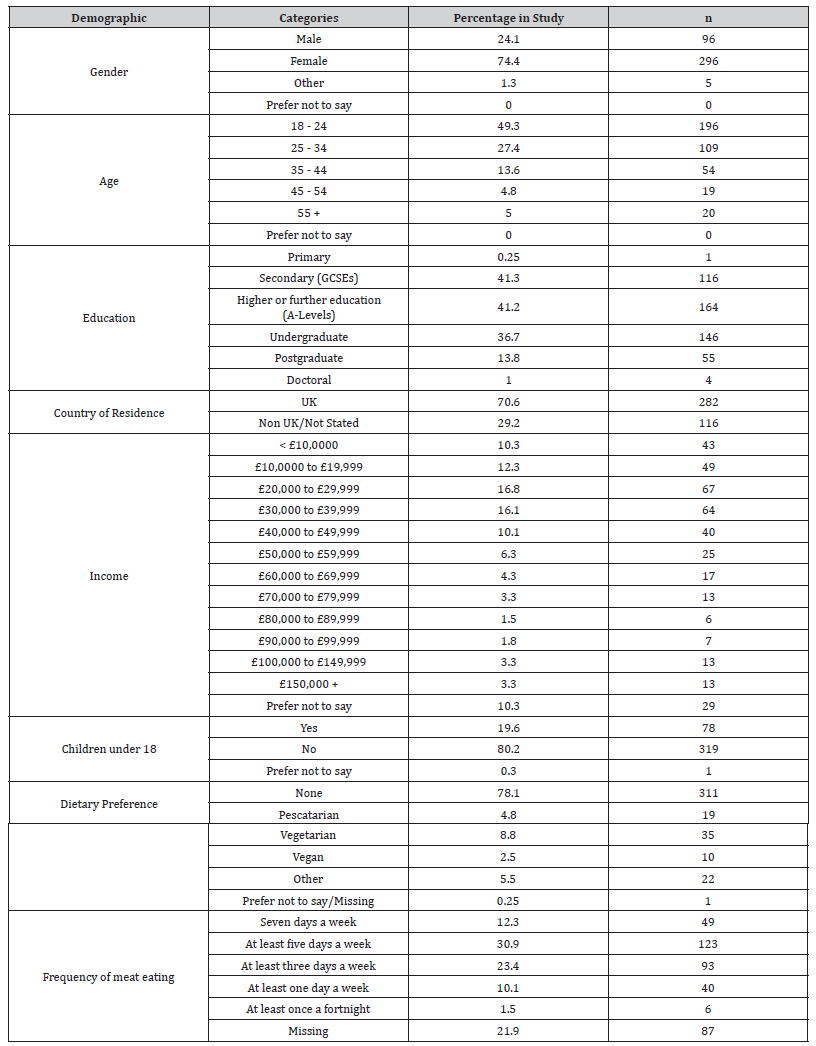

A total of 400 participants were recruited via the survey platform Prolific Academic (www.prolific.ac). Owing to a screener error in recruitment, there were 119 participants (who were not required to be located in the UK) and 281 who were UK nationals, living in the UK and aged between 18-75 years. These were merged into a final sample of 398 (following two exclusions where demographic information could not be matched ; for final sample characteristics Table 1) . Participants were told they would be asked questions about their views on methods for promoting healthier and more sustainable food choice and all gave informed consent before taking part. They were paid £1.10 for the study, which lasted approximately 10-12 minutes. Ethical approval was granted from the Queen Mary University Ethics Board - QMREC1948.

Table 1:Characteristics of Sample.

Questionnaire and Procedure

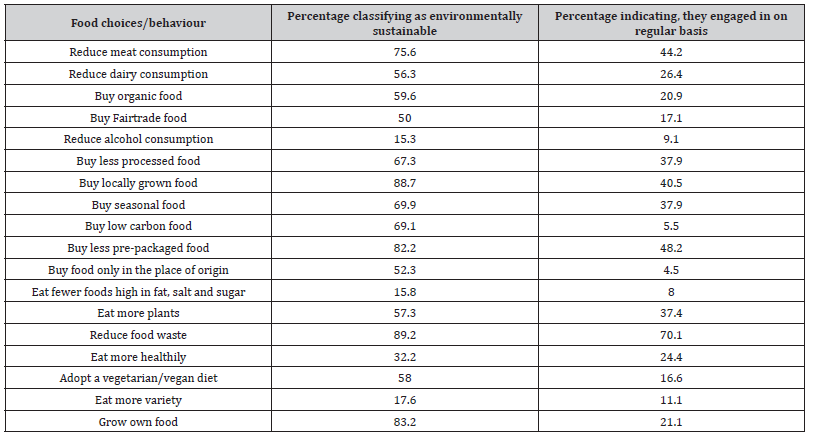

The study was run using Qualtrics. Participants were first asked to respond to a number of demographic questions, including age, gender, education, income and if they had children under 18 years (Table 1). Participants were also asked to indicate if they had any specific dietary preferences and if applicable, they were asked how frequently they ate meat. Firstly, participants were asked to indicate their general motivation to change their shopping habits in line with (a) more environmentally sustainable food choices [66] and (b) more nutritional food choices, on a slider scale from 0 (No motivation to change) to 100 (Completely motivated to change) [4,62]). On the next screen, they were asked to write what they understood by the term ‘environmentally sustainable food choices’ in a free text response box [95]. Then, participants were presented with a list of 18 behaviours/food choices (Table 2) and asked to select those they would classify as ‘environmentally sustainable’. These behaviours/food choices were identified from the literature [48,56,67,68,4,62] and selected following discussions with food safety experts (e.g., Food Standards Agency direct communication). They were then asked to indicate which of those behaviours/food choices they selected they engaged in on a regular basis.

Table 2:Understanding Of ‘Environmentally Sustainable’ Behaviours/Food Choices.

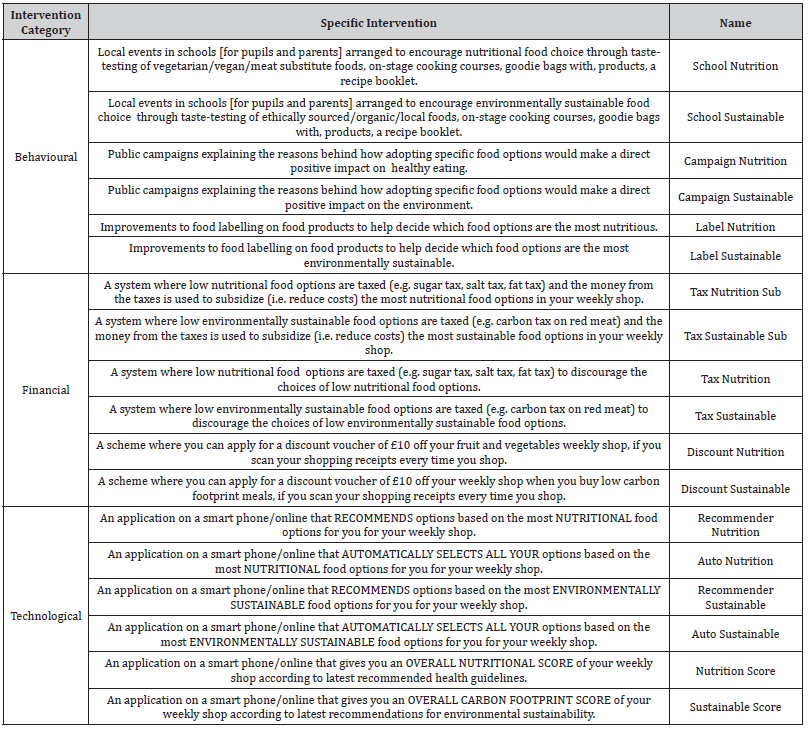

For the main part of the study, we identified three categories of interventions which could be used to elicit behaviour change: behavioural, financial and technological (smart applications), each of which consisted of six specific interventions (Table 3). These were identified from the literature (behavioural: [69-71], financial: [72,73]; technological: [53,56,60]. The specific dependent variables on which responses were captured (e.g. judgments of effectiveness [behaviour change], judgments of ethicality) were drawn from previous studies examining behavioural interventions in food domains as well as other related domains (e.g. exercise, alcohol consumption) [48,68, 4, 62].

Table 3:Interventions Referred to in the Study.

For each specific type of intervention, participants were asked to rank the six specific interventions (presented randomly) in the order that they would be willing to adopt them, from most to least likely to adopt. After ranking, participants were presented with the intervention they were most willing to adopt, and asked a) to what extent they thought it would encourage them to positively change their shopping habits and b) to what extent they thought it was ethical (where ethical meant that even if the method was implemented, they would still be able to overrule it and choose what they wanted freely). Finally, participants were asked to indicate their endorsement in terms of whether they would want each method of influence to be used to influence their food choices, answering ‘Yes’ or ‘No’ for the three categories of intervention (i.e., behavioural, financial, technological). Then participants were thanked, debriefed, and re-directed to claim their reward.

Statistical Analyses

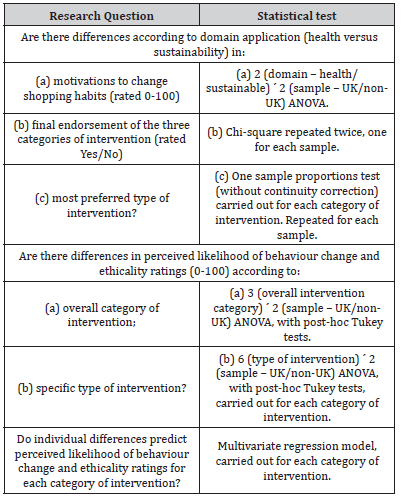

All analyses were run using R [74] in R Studio version 4.2.2 (2022-10-31) [75] using the stats package and summary tools package version 1.0.1 [76]. 95% confidence intervals were generated by the effect size package [77] and are two sided unless otherwise stated. For details of specific analytic techniques, Table 4.

Table 4:Research Questions and Associated Analytic Technique.

Results

Results reported are for the final combined sample. Where there were differences according to UK and non-UK samples, these are explicitly presented in the text. To begin, we consider motivations to change shopping habits, and final endorsement of the three categories of interventions. In the former case, participants were significantly more motivated to change their shopping habits in line with more healthy, nutritional food choices (M= 70.58) versus more environmentally sustainable choices (M=62.54), F (1,792) = 25.38, p < .001, ηp2 = 0.03, CI = 0.01, 0.06. In the latter case regarding endorsements, there was a significant difference, with technological (84.9%) and financial (87.9%) methods preferred more than behavioural methods (74.4%), c2(2) = 27.9, p < .001, Cramer’s V = 0.26, CI = 0.14, 0.35 though this difference was not observed in the non-UK sample c2(2) = 4.90, p = .09, Cramer’s V = 0.16, CI = 0.00, 0.35.

Initial Preferences for Interventions

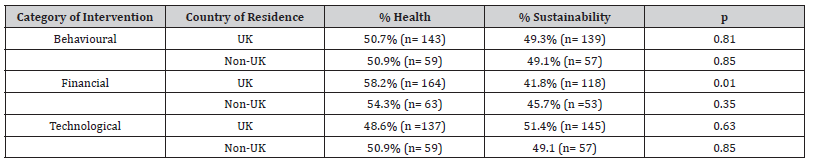

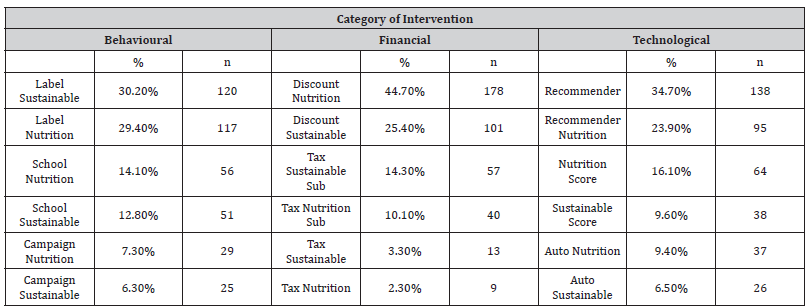

For each of the three categories of interventions, we examined which of the specific types was ranked as most preferable, and whether this significantly differed according to domain (i.e., whether they were designed to target health or environmental sustainability, Table 5). For behavioural and technological interventions, there was no significant difference in preferences according to domain. For financial interventions, however, a higher proportion of participants preferred interventions which targeted health (though this was not observed in the non-UK sample). Looking in more detail, Table 6 depicts how many participants picked the specific type of intervention as their most preferred. The most popular options were the same across both samples. Overall, across all of the interventions, the most popular type was discounts for nutritional foods (n= 178).

Table 5:Most Preferred Intervention by Category, Country of Residence and Domain.

Table 6:Most Preferred Intervention by Specific Type.

Perceived Likelihood of Behaviour Change and Ethicality

For each of the specific interventions participants ranked as their most preferred, they were asked to rate (a) the perceived likelihood of the intervention positively changing their shopping habits, and (b) perceived ethicality (i.e., where even if the intervention was implemented, they would still be able to overrule it and choose what they wanted freely). We subsequently investigated whether these ratings differed by i) overall category of intervention, and ii) specific type of intervention.

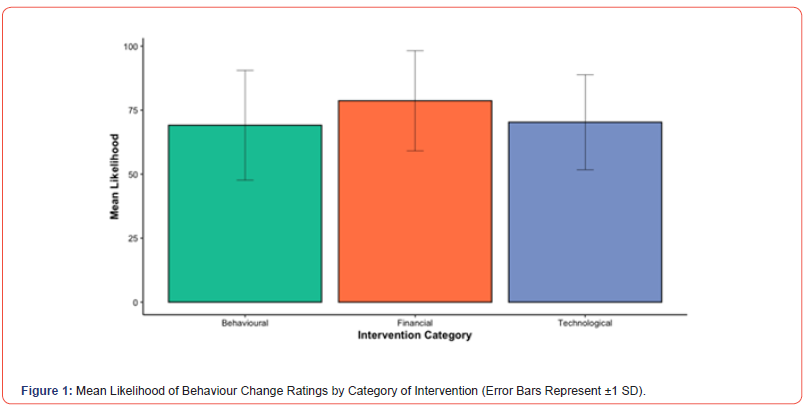

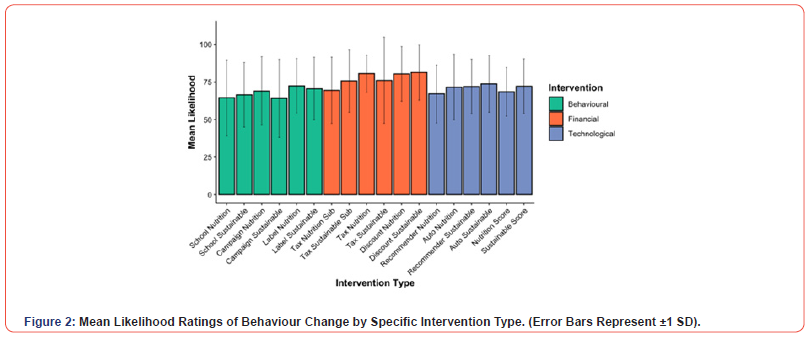

Likelihood of behaviour change

There was a significant effect of overall category of intervention on perceived likelihood ratings F(2,1188) = 27.27, p < .001, ηp2 = 0.04, CI = 0.02, 0.07, but no significant effect of sample, F(1,1188) = 0.70, p = .40, nor an interaction F(2,1188) = 0.52, p= .60. Results of post-hoc Tukey HSD tests showed that the mean likelihood was significantly different between financial and technological interventions (p < .001, d = 0.41, CI = 0.30, 0.51) and financial and behavioural interventions (p < .001, d= 0.41, CI= 0.31, 0.51), such that financial interventions were perceived as most likely to lead to positive behaviour change (Figure 1). Looking in more detail at the specific type, for the behavioural and technological interventions, we observed no significant effect of intervention (behavioural – F[5,386] = 1.64, p= .15, technological – F[5,386] = 1.2, p= .31), sample (behavioural – F[1,386] = 0.03, p= .87, technological – F[1,386] = 0.1, p= .76), nor an interaction (behavioural – F[5,386] = 0.63, p= .15, technological F[5,386] = 0.95, p= .45) on perceived likelihood of behaviour change ratings. In contrast, for the financial interventions, we did observe a significant effect of type of intervention, F(5,386) = 2.79, p < .05, ηp2 = 0.03, CI = 0.00, 0.07, but no effect of sample, F(1,386) = 2.3, p= .13, nor an interaction F(5,386) = 0.93, p= .46. Results of post-hoc Tukey HSD tests showed that mean likelihood of behaviour change ratings were significantly different between the tax nutrition subsidy and the discounts for nutrition (p = .02, d= 0.57, CI = 0.23, 0.92) and sustainable options (p < .01, d= 0.61, CI = 0.23, 0.98), with higher likelihood ratings of behaviour change for the discounts (Figure 2).

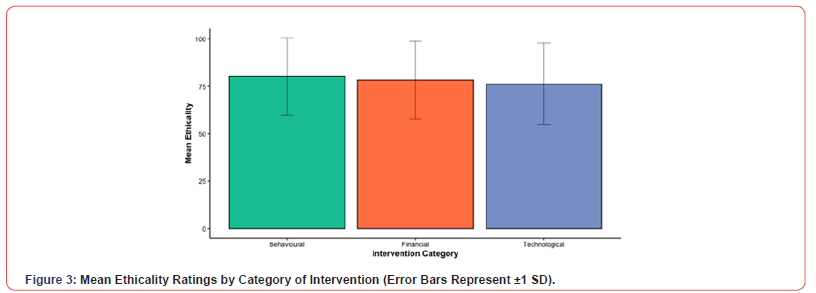

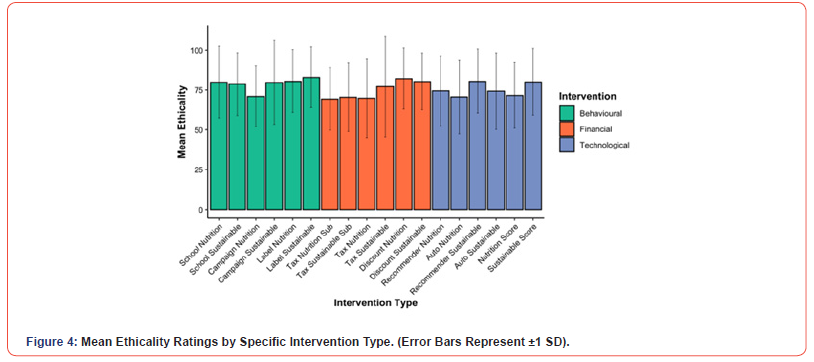

Ethicality appraisals

There was a significant effect of overall category of intervention on perceived ethicality ratings F(2,1188) = 3.51, p = .03, ηp2 = 0.01, CI= 0.00, 0.02 but no significant effect of sample, F(1,1188) = 0.19, p = .66, nor an interaction F(2,1188) = 0.38, p= .69. Results of post-hoc Tukey HSD tests showed that the mean ethicality was significantly different between behavioural and technological interventions (p = .02, d= 0.20, CI = 0.10, 0.30), with greater ethicality perceived for behavioural interventions (Figure 3). Looking in more detail at the specific intervention type, for the behavioural interventions, we observed no significant effect type of intervention F(5,386) = 1.67, p= .14), sample, F(1,386) = 0.18, p= .66, nor an interaction, F(5,386) = 0.20, p= .96) on perceived ethicality ratings. For the financial interventions, we observed a significant effect of type of intervention, F(5,386) = 5.30, p < .001, ηp2 = 0.06, CI = 0.02, 0.11 and no effect of sample, F(1,386) = 0.01, p= .94, nor an interaction F(5,386) = 1.34, p= .25. Results of post-hoc Tukey HSD tests showed that mean ethicality ratings were significantly different between the tax nutrition subsidy and the discounts for nutrition (p < .01, d= 0.66, CI= 0.31, 1.01) and sustainable options (p < .05, d= 0.60, CI = 0.23, 0.97), with higher ethicality ratings for the discounts (Figure 4). Ethicality ratings were also significantly different between the tax sustainable subsidy and the discounts for nutrition (p < .01, d= 0.59, CI = 0.29, 0.89) and sustainable options (p < .05, d= 0.52, CI = 0.19, 0.84), again with higher ethicality ratings for the discounts. For the technological interventions, there was a significant effect of type on ethicality ratings, F(1,386) = 2.64, p < .05, ηp2 = 0.03, CI = 0.00, 0.06, and sample, F(1,386) = 0.87, p= .35, nor an interaction between the two F(5,386) = 0.49, p= .78. However, follow up posthoc Tukey HSD tests did not reveal significant differences at the conventional p < .05 level – the difference between the nutrition score and recommender sustainable was p = .07 (d= 0.44, CI= 0.14, 0.74). Across all of the interventions, vouchers were judged as the most likely to change shopping habits and were perceived as some of the most ethical interventions (second only to labelling).

Effect of Individual Characteristics

Having considered the differences between interventions in terms of the overall perceived (a) likelihood of behaviour change and (b) perceived ethicality, we next consider whether there were also differences between individuals for each intervention. For each of the three categories of intervention, we ran a multivariate regression model, including individual characteristics as predictive factors. The finalised model structure for each category of intervention was: Behaviour Change, Ethicality ~ Age + Gender + Parental Status + Education + Income + Sample [Country of Residence] + Dietary Preferences + Motivation (Nutrition) + Motivation (Sustainable) .

Behavioural Interventions

For behavioural interventions, only two factors significantly predicted likelihood of behaviour change: motivation to change habits in line with more nutritional choices (b = 5.29, t = 4.39, p < .001, ηp2 = 0.05, CI = 0.02, 0.11) and sustainable choices (b = 5.37, t = 4.25, p < .001, ηp2 = 0.12, CI = 0.06, 0.19). The same two factors also predicted perceived ethicality, albeit less strongly (motivation nutrition - [b = 2.85, t = 2.29, p = .02, ηp2 = 0.02, CI = 0.00, 0.05] and motivation sustainable - [b = 3.16, t = 2.43, p = .02, ηp2 = 0.04, CI = 0.01, 0.09). Essentially, the higher the motivation to change habits, the more likely behavioural interventions were perceived to change behaviour, and the more ethical they were perceived to be.

Financial Interventions

For financial interventions, several factors significantly predicted efficacy of behaviour change through their use: gender (b = -5.97, t= -2.61, p < .01, ηp2 = 0.03, CI = 0.00, 0.07), income (b = -2.34, t = -2.33 p = .02, ηp2 = 0.01, CI = 0.00, 0.04), motivation to change habits in line with more nutritional choices (b = 3.30, t = 3.02, p < .001, ηp2 = 0.03, CI = 0.00, 0.07) and sustainable choices (b = 4.53, t = 3.96, p < .001, ηp2 = 0.09, CI = 0.04. 0.15. For males and those with higher incomes, the less likely financial interventions were perceived to change behaviour. The higher the motivation to change habits, the more likely such interventions were perceived to change behaviour. For ethicality, only motivation to change dietary habits was significantly predictive (b = 2.81, t = 2.33, p = .02, ηp2 = 0.02, CI = 0.00, 0.05), such that the higher the motivation, the more ethical financial interventions were perceived to be.

Technological Interventions

Similar to behavioural interventions, only motivation to change habits in line with more nutritional choices (b = 2.44, t = 2.40, p = .02, ηp2 = 0.00, 0.05) and sustainable choices (b = 7.09, t = 6.66, p < .001, ηp2 = 0.18, CI = 0.11, 0.25) predicted likelihood of behaviour change though technological interventions. For ethicality, only motivation to change habits in line with sustainable choices was significantly predictive (b = 2.81, t = 2.33, p = .02, ηp2 = 0.10, CI = 0.05, 0.16), such that the higher the motivation, the more ethical technological interventions were perceived to be.

General Discussion

The aim of the present study was to address evidential gaps regarding public appraisals of typical (e.g., behavioural, financial) and novel interventions (e.g., technological decision-support systems). The appraised interventions, when applied to increasing healthy and sustainable food consumption, were based on their ethicality and efficacy in achieving behavioural change. Along with these, respondents indicated their general motivation for changing their habits towards healthy and sustainable consumption, an overall preference of the specific types of interventions, and a final judgment as to which the three categories of interventions they would endorse.

Summary of Results

Overall, financial interventions were judged, with a moderate effect size, as more effective than behavioural and technological interventions, which aligned with our second hypothesis. Efficacy was not differentiated by which domain the interventions were applied (i.e., designed to improve healthy or sustainable consumption). When it came to ethicality, overall, there was a small effect of intervention category, with behavioural interventions appraised as more ethical than technological interventions. The lack of statistical difference between behavioural interventions and financial interventions failed to support our initial hypothesis. In fact, the only substantive differences based on ethicality were found for specific types of financial interventions. This may have been a result of the fact that perceived ethicality across the three types of interventions was fairly high (approximately 70, on a scale of 0 to 100). We found that motivations to change behaviour positively in line with nutritional aspects were greater than in line with sustainable consumption. Second, the three most preferred options of all 18 intervention types, were discounts on healthy foods (ranked first), recommender system for sustainable foods, (ranked second) and food labels signalling sustainable foods (ranked third). Third, overall endorsement rates were higher for financial and technological interventions than behavioural interventions. In the remainder of this discussion, consideration of these, along with the profile of findings with respect to ethicality and efficacy independently, and motivation, is focused on each category of interventions. This enables us to propose practical ways of drawing insights from the present findings.

Technological Interventions

Because the domain of technological developments (decisionsupport systems) in food consumption is relatively new, there is still limited work assessing the relative merits of either decisions support tools or automated decision tools compared with typical interventions (e.g., financial, behavioural). Given that adoption of decision-support tools in food retailing is expected to rise offline and particularly online [50-57,61, 78,79,] a better understanding of public appraisals is needed of the types of tools used and their function. [61] conducted several in-depth interviews with experts (i.e., academics in fields of research on recommender systems, decision aids, digital marketing, consumer decision making) and consumers to investigate appraisals of technological decisionsupport tools when used to inform healthy and sustainable food choices online. In the main, the findings suggest that experts and consumers are favourable towards tools that are tailored to individuals and provide rationales for suggested food options by way of labels and accompanying text. The value of having a decision support tool that identifies products that would be of interest to shoppers critically depends on the functionality of the system and how the options are presented. That is, favourability of a decision support tool depends on how effective it can be, which in turn depends on optimising its efficiency to recommend food options, while respecting data privacy issues, and other associated factors. Moreover, rather than fully automating shopping, the provision of a list of recommendations that could be vetoed or refined by the shopper was seen to be preferable. Clearly this also indicates that a choice preserving process is necessary for any new decisionsupport tool to be fully adopted. One concern highlighted in Jansen et al. (2023) and others [80,81] is the extent to which explicitly signalling options as sustainable are likely to backfire when it comes to actual selection of those options. Put simply, decision support tools that recommend options that have lower associated carbon emissions would simply be a turn off to consumers.

Speaking to previous concerns [61,80,81], the present findings show that there is a correspondence between motivations to eat more sustainably, and judged ethicality and efficacy of technological interventions. From a policy perspective, there is much light to be taken from the findings from this and other corresponding research [61]. Across the different types of appraisals (i.e., overall preference, overall endorsement, ethicality, efficacy), technological interventions, particularly recommender decision-support tools, fare well. The findings from the present study are especially informative because they also concern relative assessment of technological interventions to other categories of interventions, and between variants within the same category. Of all 18 variants (six of each of behavioural, financial, technological categories), the second most preferred intervention was the recommender system that presented sustainable food choices. More specifically, of the six variants of technological interventions, those that automated shopping decisions (either for health or sustainability) were preferred the least. Even when it came to final endorsements, technological interventions were equal to financial interventions, both of which exceeded rates for behavioural interventions.

If technological interventions are considered a viable means of promoting sustainable and healthy food consumption with good supporting evidence of efficacy, then communication of this would be consistent with public appraisals on this basis. Additionally, to promote adoption of recommender systems, to align with public interest, consumers should be made aware that options that suit their motivational interests are the means of creating efficiencies in their shopping routines, with a function that enables vetoing or refinement of the recommendations helps preserve their ultimate choice in what they buy. What is needed is a way to borrow from behavioural interventions, which were judged as more ethical< than technological ones. Transparency of information is key, so flagging that the tools have an inbuilt provision of explanations for recommended options through additional labelling and text to support suggested options.

Financial Interventions

Financial interventions have previously been considered as methods of inducing behavioural change, such as taxation alone [82, 26-29] or combined with subsidies [4]. Work of this kind provides a mixed picture of the extent to which different types of financial interventions are effective in increasing healthy eating or sustainable consumption. For instance, [4] showed that a redistributive pricing system was overall more effective than taxes, or behavioural change interventions (e.g., labelling, social comparisons) alone, but most effective when combined with behavioural interventions. Moreover, public appraisals of financial interventions, for promoting behavioural change either in line with healthier food options, or sustainable consumption, is mixed, with redistributive pricing systems considered more ethical than taxes alone.

Considering their relative standing to other categories of interventions, as well as different types, the present study shows that the most preferred intervention of all 18 types was discounts for healthier foods. In fact, this along with discounts on environmentally sustainable foods were ranked higher than taxes alone, and particularly redistributive pricing systems. Overall, financial interventions were estimated to be the most effective in generating behavioural change, regardless of where behavioural change was intended to be achieved and received the most endorsements. Motivational factors clearly need to be considered since those motivated to eat healthily tended to show higher ethicality judgments for financial, but that motivation towards healthy eating and sustainable consumption corresponded with appraisals of efficacy. Taken together, the findings point to specific types of financial interventions being appraised positively by the public, namely discounts.

It is important to note that, financial interventions were no less ethical than behavioural interventions that were appraised as generally highly ethical. However, if policies are designed such that regressive interventions are to be adopted, then public appraisals suggest that taxes and redistributive pricing systems are neither seen as effective or ethical as compared to discounts. There may well be empirical evidence that indicate that trialled interventions of taxes and redistributive pricing systems do lead to successful behavioural change, either in the laboratory [4] or in the field [83]. However, the findings from the present study show that they do not fare especially when compared to other categories of interventions (e.g., behavioural, technological), or against specific types of financial interventions (e.g., discounts). The practical insights from the present findings are that there is close alignment between public appraisals of, and empirical evidence for, price reductions (e.g., coupons, vouchers) on foods that are healthy and sustainable [84-86]. In fact, it is likely that the discounts in the present study were a contributing factor to the high rates of endorsement, preferences, and efficacy ratings of financial interventions overall. Moreover, given that efficacy ratings were lower for those with higher incomes adds further support to pricing systems that introduce lower costs for particular types of foods, to be promoted specifically to demographic groups that would in fact use them, and benefit from them the most.

Behavioural Interventions

Work examining the use of behavioural interventions to promote healthy eating and sustainable consumption is vast [87], and there are various positive illustrations of their efficacy [88-90], as well as concerns over their reliability [90]. One emerging trend is to treat behavioural interventions as providing a supporting role to other common regulatory tools [3,91,92], or to combine behavioural interventions. The principal problem for behavioural change interventions, and for that matter, most efforts to support behavioural change, is that even if they do initially show adjustments in line with predictions, the change does not continue over time. When it comes to food consumption habits, the dynamics of personal, economic, social and cultural factors may conflict in ways to resist any sustained change. In fact, this was observed in studies on behavioural change of dietary habits as early as the 1940s (Lewin, 1942). Wood and Neal (2016) provide an analysis of research on behavioural change in the food domain which show the commonality of what they refer to as the ‘triangular relapse pattern’. Prior to the intervention, a sample shows high intake of high energy content food. During and shortly after a behavioural intervention, there is a sharp shift to lower intake of high energy content food and increase in intake of nutritionally rich foods, and then a regression back to pre-intervention levels, worse still if they regress back further than at the start. Experiences of this kind are likely to be common to most, given that changing eating habits is one of the most common areas where people are motivated to change. In line with this, the present study shows that motivations to increase healthier eating is stronger than for sustainable consumption. This might explain why, in the present study, behavioural change interventions were the least endorsed, and had overall lower efficacy ratings compared to financial interventions. The third preferred of all 18 types of interventions was food labels that indicated the environmental sustainability of food products. The next most preferred was food labels that signalled nutritional values of foods. Taken together, there is strong preference for food labels, and in the main, behavioural interventions are judged as highly ethical. This is most likely because all of the examples included in the present study were transparent, and explicitly choice preserving.

Building on insights from the present findings, and taken together with empirical work, from a policy perspective, labelling on packaged food is positively appraised by the public, but food labelling of various kinds designed to promote behavioural change fail to achieve reliable and sustainable change (for recent review, [3]). However, if combined with interventions that generate actual behavioural change, then there are complementary benefits to communicating interventions that are employed that are viewed by the public as ethical and are empirically shown to be efficacious.

Limitations and Future Directions

Whilst we sought to include a diverse sample of participants in the current study, the distribution of non-UK to UK participants was skewed. Although analyses were conducted to assess the extent to which sample differences affected the patterns of findings, support for food policies has been shown to differ by country [31]. Follow up work should therefore address the imbalance so that a broader range of countries would be included to assess the generality of public appraisals revealed presently.

Second, the main focus of the present study was to examine public appraisals of three categories of interventions, designed to improve healthy or sustainable consumption. However, this excludes interventions that target both at the same time and the possibility that appraisals could be additive. A follow up study could further examine whether public appraisals for combinations of interventions as well as interventions designed to target more than one behavioural outcome.

Conclusion

Public appraisals of three categories of interventions (behavioural, financial, technological) reveal financial interventions as more efficacious, but no less ethical, than behavioural interventions. In the main, using a distributive pricing system (Taxes + Subsidies) appeared to be judged as the least ethical of all, and of the least efficacious for either healthy or sustainable consumption. Using discounts in either context was appraised as highly ethical and efficacious, and ranked the highest in terms of overall preferred intervention. In general, technological interventions were marginally less ethical than behavioural interventions, and less efficacious than financial interventions. However, overall endorsement accorded with appraisals of efficacy rather than ethicality, given that the public considered that financial interventions and technological interventions should be adopted more than behavioural interventions.

Data Availability

All materials and raw data are available h t t p s : / / o s f . i o / 6 8 a 4 u / ? v i e w _ only=3f13b2418ad54ba98d7d1a748b07a13a

Funding

The Food Standards Agency (UK) financially supported the empirical work, specifically the financial reimbursement that participants received when completing the survey work. All other aspects of the design, preparation of materials, and manuscript preparation where not financial supported by the Food Standards Agency. The opinions and conclusions articulated here do not represent those of the Food Standards Agency.

Declarations of Interest

None

References

- Hawkes C, Smith TG, Jewell J, Wardle J, Hammond RA, et al. (2015) Smart food policies for obesity prevention. The Lancet 385(9985): 2410-2421.

- Meier J, Andor MA, Doebbe FC, Haddaway NR, Reisch LA (2022) Do green defaults reduce meat consumption?. Food Policy 110(1):

- Osman M, Jenkins S (2022) Consumer responses to food labelling: A rapid evidence review. Food Standards Agency.

- Osman M, Schwartz P, Wodak S (2021) Sustainable consumption: what works best, carbon taxes, subsidies and/or nudges?. Basic and Applied Social Psychology 43(3): 169-194.

- Reisch LA (2021) Shaping healthy and sustainable food systems with behavioural food policy. European Review of Agricultural Economics 48(4): 665-693.

- Vecchio R, Cavallo C (2019) Increasing healthy food choices through nudges: A systematic review. Food Quality and Preference 78(6):

- Cairney P (2016) The politics of evidence-based policy making. Springer.

- Cairney P, Oliver K (2020) How should academics engage in policymaking to achieve impact? Political Studies Review 18(2): 228-244.

- Pluchinotta I, Daniell KA, Tsoukiàs A (2022) Supporting Decision-Making within the Policy Cycle: Techniques and Tools. In The Routledge Handbook of Policy Tools. 235-244.

- Osman M, Nelson W (2019) How can food futures insight promote change in consumers’ choices, are behavioural interventions (eg., nudges) the answer?. Futures 111(6): 116-122.

- Bastian B (2019) Changing ethically troublesome behaviour: The causes, consequences, and solutions to motivated resistance. Social Issues and Policy Review 13(1): 63-92.

- Bolton G, Dimant E, Schmidt U (2020) When a nudge backfires: Combining (im) plausible deniability with social and economic incentives to promote behavioural change. SSRN.

- Osman M, McLachlan S, Fenton N, Neil M, Löfstedt R, et al. (2020) Learning from behavioural changes that fail. Trends in Cognitive Sciences 24(12): 969-980.

- Seafood Industry report (2013) The Sea Fish Industry Authority annual report and accounts 2013 to 2014.

- Seafood Industry report (2016) UK sea fisheries annual statistics report 2016.

- Anderson E N (2014) Everyone eats: Understanding food and culture. NYU Press.

- Torkkeli K, Janhonen K, Mäkelä J (2021) Engagements in situationally appropriate home cooking. Food, Culture & Society 24(3): 368-389.

- Aktaş-Polat S, Polat S (2020) A theoretical analysis of food meaning in anthropology and sociology. Tourism: An International Interdisciplinary Journal 68(3): 278-293.

- Murcott A (2019) Introducing the sociology of food and eating. Bloomsbury Publishing.

- Pfeiler TM, Egloff B (2020) Personality and eating habits revisited: Associations between the big five, food choices, and Body Mass Index in a representative Australian sample. Appetite 149: 104607.

- Sobal J, Bisogni CA, Jastran M (2014) Food choice is multifaceted, contextual, dynamic, multilevel, integrated, and diverse. Mind, Brain, and Education 8(1): 6-12.

- Stroebele N, De Castro JM (2004) Effect of ambience on food intake and food choice. Nutrition 20(9): 821-838.

- Cullerton K, Baker P, Adsett E, Lee A (2021) What do the Australian public think of regulatory nutrition policies? A scoping review. Obes Rev 22(1): e13106.

- Cranney L, Thomas M, Cobcroft M, Drayton B, Rissel C, et al. (2022) Community support for policy interventions targeting unhealthy food environments in public institutions. Health Promotion J Austr 33(3): 618-630.

- Sainsbury E, Hendy C, Magnusson R, Colagiuri S (2018) Public support for government regulatory interventions for overweight and obesity in Australia. BMC Public Health 18(1): 1-11.

- Grunseit AC, Rowbotham S, Crane M, Indig D, Bauman AE, et al. (2019) Nanny or canny? Community perceptions of government intervention for preventive health. Critical Public Health 29(3): 274-289.

- Pettigrew S, Booth L, Dunford, E, Scapin T, Webster J, et al. (2023) An examination of public support for 35 nutrition interventions across seven countries. Eur J Clin Nutr 77(2): 235-245.

- Pollard CM, Daly A, Moore M, Binns CW (2013) Public say food regulatory policies to improve health in Western Australia are important: population survey results. Aust N Z J Public Health 37(5): 475-482.

- Watson W, Weber MF, Hughes C, Wellard L, Chapman K (2017) Support for food policy initiatives is associated with knowledge of obesity-related cancer risk factors. Public health res pract 27(5): 27341703.

- Polden M, Robinson E, Jones A (2022) Assessing public perception and awareness of UK mandatory calorie labelling in the out‐of‐home sector: Using Twitter and Google trends data. Obes Sci Pract 9(5): 459-467.

- Kwon J, Cameron AJ, Hammond D, White CM, Vanderlee, L, et al. (2019) A multi-country survey of public support for food policies to promote healthy diets: Findings from the International Food Policy Study. BMC Public Health 19(1): 1

- Bălan C (2020) How does retail engage consumers in sustainable consumption? A systematic literature review. Sustainability 13(1): 96.

- Ejelöv E, Nilsson A (2020) Individual factors influencing acceptability for environmental policies: a review and research agenda. Sustainability 12(6): 2404.

- Hoek AC, Pearson D, James SW, Lawrence MA, Friel S (2017) Shrinking the food-print: A qualitative study into consumer perceptions, experiences and attitudes towards healthy and environmentally friendly food behaviours. Appetite 108: 117-131.

- Vanhonacker F, Van Loo EJ, Gellynck X, Verbeke W (2013) Flemish consumer attitudes towards more sustainable food choices. Appetite 62: 7-16.

- Wojciechowska-Solis J, Barska A (2021) Exploring the preferences of consumers’ organic products in aspects of sustainable consumption: The case of the Polish consumer. Agriculture 11(2):

- Worsley A, Wang WC, Burton M (2015) Food concerns and support for environmental food policies and purchasing. Appetite 91: 48-55.

- Taufique KM, Nielsen KS, Dietz T, Shwom R, Stern, et al. (2022) Revisiting the promise of carbon labelling. Nature Climate Change 12(2): 132-140.

- Ammann J, Arbenz A, Mack G, Nemecek T, El Benni N (2023) A review on policy instruments for sustainable food consumption. Sustainable Production and Consumption 36: 338-353.

- Reisch L, Eberle U, Lorek S (2013) Sustainable food consumption: an overview of contemporary issues and policies. Sustainability: Science, Practice and Policy 9(2): 7-25.

- Deprá M C, Dias R R, Zepka L Q, Jacob-Lopes E (2022) Building cleaner production: How to anchor sustainability in the food production chain? Environmental Advances 9(9): 100295.

- Filho L W, Setti AFF, Azeiteiro U M, Lokupitiya E, Donkor F K, et al. (2022) An overview of the interactions between food production and climate change. Science of the Total Environment 838(Pt 3): 156438.

- Leahy S, Clark H, Reisinger A (2020) Challenges and prospects for agricultural greenhouse gas mitigation pathways consistent with the Paris Agreement. Frontiers in Sustainable Food Systems 4:

- Filimonau V, Lemmer C, Marshall D, Bejjani G (2017) ‘Nudging’ as an architect of more responsible consumer choice in food service provision: The role of restaurant menu design. Journal of Cleaner Production 144: 161-170.

- Kenny TA, Woodside JV, Perry IJ, Harrington JM (2023) Consumer attitudes and behaviours toward more sustainable diets: a scoping review. Nutr Rev 81(12): 1655-1679.

- Bang H M, Shu S B, Weber E U (2020) The role of perceived effectiveness on the acceptability of choice architecture. Behavioural Public Policy 4(1): 50–70.

- Bos C, Lans I V D, Van Rijnsoever F, Van Trijp H (2015) Consumer acceptance of population-level intervention strategies for healthy food choices: The role of perceived effectiveness and perceived fairness. Nutrients 7(9): 7842–7862.

- Gold N, LinvY, Ashcroft R, Osman M (2023) ‘Better off, as judged by themselves’: do people support nudges as a method to change their own behavior?. Behavioural Public Policy 7(1); 25-54.

- Reisch LA, Sunstein CR, Gwozdz W (2017) Beyond carrots and sticks: Europeans support health nudges. Food Policy 69(12): 1-

- Punia S, Shankar S (2022) Predictive analytics for demand forecasting: A deep learning-based decision support system. Knowledge-Based Systems 258(1):

- Xia F, Chatterjee R (2022) Multicategory choice modeling with sparse and high dimensional data: A Bayesian deep learning approach. Decision Support Systems 157(2):

- Bodike Y, Heu D, Kadari B, Kiser B, Pirouz M (2020) A novel recommender system for healthy grocery shopping. In Advances in Information and Communication: Proceedings of the 2020 Future of Information and Communication Conference (FICC), Volume 2 (pp. 133-146). Springer International Publishing.

- De Bellis E, Johar G V (2020) Autonomous shopping systems: Identifying and overcoming barriers to consumer adoption. Journal of Retailing 96(1): 74-87.

- Hallikainen H, Luongo M, Dhir A, Laukkanen T (2022) Consequences of personalized product recommendations and price promotions in online grocery shopping. J Retailing and Consumer Services 69(1):

- Kabadurmus O, Kayikci Y, Demir S, Koc B (2023) A data-driven decision support system with smart packaging in grocery store supply chains during outbreaks. Socio-Economic Planning Sciences 85:

- Lawo D, Neifer T, Esau M, Stevens G (2021) Buying the ‘Right’ Thing: Designing Food Recommender Systems with Critical Consumers. In Proceedings of the May 2021 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems. 1-13.

- Pillai R, Sivathanu B, Dwivedi YK (2020) Shopping intention at AI-powered automated retail stores (AIPARS). Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services 57(3): 102207.

- East R (2022) Online grocery sales after the pandemic. International Journal of Market Research 64(1): 13-18.

- Belciug S, Gorunescu F (2020) A brief history of intelligent decision support systems. Intelligent Decision Support Systems-A Journey to Smarter Healthcare pp.57-70.

- A (2021) Mobile apps as a sustainable shopping guide: The effect of eco-score rankings on sustainable food choice. Appetite 167:

- Jansen LZ, Van Loo EJ, Bennin KE, van Kleef E (2023) Exploring the role of decision support systems in promoting healthier and more sustainable food shopping: A card sorting study. Appetite 188:

- Osman M, Thornton K (2019) Traffic light labelling of meals to promote sustainable consumption and healthy eating. Appetite 138: 60-71.

- Feucht Y, Zander K (2017) Consumers' willingness to pay for climate-friendly food in European countries. Proceedings in Food System Dynamics 360-377.

- Grummon AH, Lee CJ, Robinson TN, Rimm EB, Rose D (2023) Simple dietary substitutions can reduce carbon footprints and improve dietary quality across diverse segments of the US population. Nature Food 4(11): 966-977.

- Randers L, Thøgersen J (2023) From attitude to identity? A field experiment on attitude activation, identity formation, and meat reduction. Journal of Environmental Psychology 87(1):

- Aprile M C, Caputo V, Nayga J, R M (2016) Consumers’ preferences and attitudes toward local food products. Journal of Food Products Marketing 22(1): 19-42.

- Mancini P, Marchini A, Simeone M (2017) Which are the sustainable attributes affecting the real consumption behaviour? Consumer understanding and choices. British Food Journal 119(8): 1839-1853.

- Osman M, Fenton N, Pilditch T, Lagnado D, Neil M (2018) Whom do we trust on social policy interventions?. Basic and Applied Social Psychology 40(5): 249-268.

- De Keyzer W, Van Caneghem S, Heath A L M, Vanaelst B, Verschraegen M, et al. (2012) Nutritional quality and acceptability of a weekly vegetarian lunch in primary-school canteens in Ghent, Belgium: ‘Thursday Veggie Day’. Public Health Nutrition 15(12): 2326-2330.

- Snyder LB (2007) Health communication campaigns and their impact on behavior. Journal of Nutrition Education and Behavior 39(2): S32-S40.

- Cecchini M, Warin L (2016) Impact of food labelling systems on food choices and eating behaviours: a systematic review and meta‐analysis of randomized studies. Obesity Reviews 17(3): 201-210.

- Niebylski ML, Redburn KA, Duhaney T, Campbell NR (2015) Healthy food subsidies and unhealthy food taxation: A systematic review of the evidence. Nutrition 31(6): 787-795.

- Betty A L (2013) Using financial incentives to increase fruit and vegetable consumption in the UK. Nutrition Bulletin 38(4): 414-420.

- R Core Team (2022) R: A language and environment for statistical computing. Vienna, Austria.

- R Studio Team (2022) RStudio: Integrated Development Environment for R. Posit Software, PBC, Boston, MA.

- Comtois D (2022) summarytools: Tools to Quickly and Neatly Summarize Data. R package version 1.0.1

- Ben-Shachar, Daniel Lüdecke Dominique, Makowski (2020) effectsize: Estimation of Effect Size Indices and Standardized Parameters. Journal of Open-Source Software 5(56): 2815.

- Bodike Y, Heu D, Kadari B, Kiser B, Pirouz M (2020) A novel recommender system for healthy grocery shopping. In Advances in Information and Communication: Proceedings of the 2020 Future of Information and Communication Conference (FICC), Volume 2 (pp. 133-146). Springer International Publishing.

- Granheim SI, Løvhaug AL, Terragni L, Torheim LE, Thurston M (2022) Mapping the digital food environment: a systematic scoping review. Obesity Reviews 23(1):

- Demartini E, Vecchiato D, Finos L, Mattavelli S, Gaviglio A (2022) Would you buy vegan meatballs? The policy issues around vegan and meat-sounding labelling of plant-based meat alternatives. Food Policy 111(2): 102310.

- Krpan D, Houtsma N (2020) To veg or not to veg? The impact of framing on vegetarian food choice. Journal of Environmental Psychology 67:

- Hagmann D, Ho EH, Loewenstein G (2019) Nudging out support for a carbon tax. Nature Climate Change 9(6): 484-

- Gren IM, Hoglind L, Jansson T (2019) Refunding of € a climate tax on food consumption in Sweden (Working Paper Series/Swedish). University of Agricultural Sciences, Department of Economics, 39.

- Gittelsohn J, Rowan M, Gadhoke P (2012) Interventions in small food stores to change the food environment, improve diet, and reduce risk of chronic disease. Preventing Chronic Disease 9(2): E59.

- Gittelsohn J, Trude ACB, Kim H (2017) Pricing strategies to encourage availability, purchase, and consumption of healthy foods and beverages: A systematic review. Preventing Chronic Disease 14: E107.

- Polacsek M, Moran A, Thorndike AN, Boulos R, Franckle RL, et al. (2018) A supermarket double-dollar incentive program increases purchases of fresh fruits and vegetables among low-income families with children: the Healthy Double Study. J Nutr Educ Behav 50.

- Verplanken B, Orbell S (2022) Attitudes, habits, and behaviour change. Annu rev psychol 73: 327-352.

- Bauer J M, Aarestrup S C, Hansen P G, Reisch L A (2022) Nudging more sustainable grocery purchases: behavioural innovations in a supermarket setting. Technological Forecasting and Social Change 179: 121605.

- Lindstrom KN, Tucker JA, McVay M (2023) Nudges and choice architecture to promote healthy food purchases in adults: A systematized review. Psychol Addict Behav 37(1): 87-

- Maier M, Bartoš F, Stanley TD, Shanks DR, Harris AJ, et al. (2022) No evidence for nudging after adjusting for publication bias. Proc Natl Acad Sci 119(31):

- Osman M, McLachlan S, Fenton N, Neil M, Löfstedt R, et al. (2020) Learning from behavioural changes that fail. Trends in Cognitive Sciences 24(12): 969-980.

- Wood W, Neal DT (2016) Healthy through habit: Interventions for initiating & maintaining health behaviour change. Behavioural Science & Policy 2(1): 71-83.

- Nuffield Council on Bioethics (2007) Public health: ethical issues.

- Potter C, Bastounis A, Hartmann-Boyce J, Stewart C, Frie K, et al. (2021) The effects of environmental sustainability labels on selection, purchase, and consumption of food and drink products: a systematic review. Environ Behav 53(8): 891-925.

- Whittall B, Warwick SM, Guy DJ, Appleton KM (2023) Public understanding of sustainable diets and changes towards sustainability: A qualitative study in a UK population sample. Appetite 181: 106388.

-

Magda Osman and Sarah C Jenkins*. Magda Osman and Sarah C Jenkins* How do Behavioural, Financial and Technological Interventions Compare in the Public’s Mind when it comes to Health and Sustainability?. Sci J Research & Rev. 4(2): 2023. SJRR. MS.ID.000585.

Taxes; Subsidies; recommender systems; regressive policy; autonomy; public attitudes

-

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.