Research Article

Research Article

Closed-Circuit Television within Residential and Nursing Care Homes in Atlantic Canada: Exploring Policy in the UK and Nova Scotia

Lynn LeVatte1*, Ruth Onafuye2, Kristin Orourke3 and Karen Kennedy4

1Department of Education, Cape Breton University, Canada

2PhD Student, University of Greenwich, UK

3Department of Education, Cape Breton University, Canada

4Department of Nursing, Cape Breton University, Canada

Lynn LeVatte, Department of Education, Cape Breton University, Canada.

Received Date:August 18, 2023; Published Date:September 22, 2023

Abstract

Safety and security have been established as critical pieces of care for individuals within residential or nursing care homes. Many residents of care home facilities may have complicated medical & cognitive challenges. Utilizing Closed Captioning Television (CCTV) within a care home setting has been investigated to determine effectiveness and purpose for supporting patient care. In Nova Scotia and the United Kingdom, care homes provide 24-hour services for individuals requiring additional supports for a variety of health and safety reasons. Further to this, there are many types and sizes of care homes that are operational. These may include many variations of licensed care homes such as adult long term nursing care, small option homes, residential care facilities and regional rehabilitation homes.

The purpose of this paper is to determine the general policy usage for CCTV within care homes in Nova Scotia and the United Kingdom. Nine (n=9) care home administrators in Nova Scotia completed telephone and online questions specific to care home policy and practice for the use of CCTV. A qualitative method with semi structured interviews were employed. Data was coded and analyzed within a thematic approach. Evidence suggested that CCTV was employed within larger nursing care facilities, but not operated within smaller group home settings. Findings detailed the general purpose of usage, locations of use within the care home and recording data protocols. A preliminary comparison was noted within policy usage for CCTV within the United Kingdom and Nova Scotia.

Keywords:Care homes; Nursing homes; Safety; Elder care; Disability; CCTV; Long term care policy

Introduction

The purpose of this paper is to investigate the usage of CCTV within residential care homes through a policy lens. Exploring the general practice for this specific technology and which types of care homes is critical. In Canada and other countries such as the United Kingdom, facility-based care homes (long-term residential care homes or “nursing” care homes) are a vital part of social infrastructure, providing live-in, 24-hour support and accommodation to individuals whose care needs extend beyond that which can be provided [1]. Individuals may be placed within care homes for a variety of reasons.

This may include complex medical needs, limited social or cognitive issues [2]. Gil [3] alluded to a controversial technology which has been investigated. This is the use of Closed-Captioned Television (CCTV) within a care home setting. Reports and public commentaries highlight innumerable crises within Canada’s longterm care sector. With clear links to inadequate public sector services and sociodemographic aging, evidence of acute staffing shortages, care facilities that are closing or unable to open, inadequate care levels or long wait lists for care, escalating violence, accident and injury rates, and high death rates in care homes [3].

This research employed semi structured interviews with care home administrators in Nova Scotia and compares finding with that as documented through research from the United Kingdom. The interviews and fieldnotes revealed assumptions, policy practice and usage of CCTV or rationale for not using CCTV within 9 various care home settings in Nova Scotia. Safety and security for the ageing population within long-term care is a topic that has become increasingly relevant as the global ageing demographic trend continues [4]. A vital characteristic of the physical environment of care homes is safety and security, access and exiting the site. Many facilities have policies and mechanisms in place that govern exiting, access and security, and there is a pressing need to investigate the effects that these features have on the health and quality of life and care that residents experience [2].

Closed Circuit Television (CCTV)

Closed circuit television (CCTV) refers to the use of video cameras to transmit signals to a specific place with a set of monitors. Currently, CCTV plays a significant role in protecting the public and implementing security [5]. According to Simpson [6], we live in a surveillance society. If you live or work in a town or city, wherever you go, whatever you do, your actions are likely to be captured on camera. This is no more so than in the United Kingdom, the world’s surveillance capital. Researchers estimate that there are over 7 million Closed Circuit Television (CCTV) cameras in the UK, with just under one million of those in London [6]. The use of Closed-Circuit TV is used in various formats and purposes within the homes. Each province in Canada as well as regions in the United Kingdom have legislation to address usage/ consent for CCTV.

During the past few years, care home administrators have come under increased pressure to do more to stop abuse taking place in care homes. Secret filming shown on television programmes such as Panorama, which revealed the abuse which occurred at Winterbourne view care home [7]. In 2016, Manthorpe et al. investigated the impact of care home practices in the United Kingdom and usage of CCTV. The exposure of care home practices by a television program led to critical debate in England about roles of CCTV with care homes. Findings from interviews revealed that while care staff were affected by the scandal in media concerning social care, they didn’t focus on the media stories. Additionally, staff reported that many ideas are required for change to improve client practice [8]. Currently, in England, mental health service providers are exploring wider use of CCTV to review incidents of seclusion or restraint in response to high-profile abuse of vulnerable patients with learning disabilities and/ or mental health problems in institutional settings [9] Perhaps unsurprisingly, this followed the vivid and shocking exposure of bullying and abusive behaviour by staff, when undercover television reporters working as healthcare staff wore hidden digital cameras [6].

Clients in Care

United Kingdom

According to Niemeijer et al., (2010) various population trends show that there is an increase in aging societies. The authors also found that as the number of people with cognitive disabilities rise, concurrently, the number of potential family members and formal caregivers are decreasing. In agreement, Gage et al. (2012) stated that, older people living in care homes in England have complex health needs due to a range of medical conditions. Additionally, the British Geriatrics Society, posited that older people living in care homes may be experiencing other mental health issues, in particular loneliness and isolation, especially if they have been bereaved or have found that they have outlived many of their friends and family members (Gil et al., 2016).

Nova Scotia

Nova Scotia’s population aged 65 years and older increased 17.1% from 2016 to 2021 and accounted for 22.2% of total population in 2021, up from 19.9% in 2016 [10,11]. The fact is a massive population shift is underway. The world is aging, and so is Nova Scotia. The first of the baby boomers have turned 70. By 2030, it is estimated that more than one in four Nova Scotians will be aged 65 and over. Longer life expectancies and lower birth rates mean that, from now on, our population will be older [1]. In Nova Scotia, several types of care homes exist and operate within the province.

Methodology

Data Collection

This qualitative study involved semi structured telephone interviews. Six questions were asked to participants to determine policy surrounding usage of CCTV. Responses were recorded with permission using a handheld audio recording device and the App Voice Recording on a Smartphone. A selected time was scheduled in advance to meet the availability of the care home administrators.

Recruitment

Sampling was purposive in nature, as it was determined that administrators from Care Homes in Nova Scotia were specifically required for this study. Administrators were invited to partake in the study and recruited with an email invitation via the public database of Care Home facilities in NS. Additionally, health care managers who were known to researchers through various community health initiatives were recruited to participate. According to the Province of NS [12], there are 84 Long Term Care facilities located in the province. Additionally, there are approximately 66 residential care homes. Participants (n=9) were administrators of long-term care nursing /residential care homes.

In this study, 4 Male and 5 Female participated. Within the data collection methods, interviews were completed with individual participants and researchers composed supplementary field notes to record nonverbal communication. Data analysis methods included coding methods and the continued comparison of data (i.e., comparing data with codes, codes within codes and various categories to data) to develop concepts and their relationships (Rieger, 2019).

The variables used to purposively recruit were:

I. Employed as a Manager of Residential Care Facility

II. Employed as a Manager of Long-Term Care Nursing Home

III. Employed within an Administration Role in Long-Term

Care Home or Residential Care Facility (Director of Nursing,

Director of Recreation, Director of Diabetic Care…)

Ethics

Research Ethics were applied and received from Cape Breton University Research Ethics Board.

Findings

This study examined the policy usage of CCTV with care homes within Nova Scotia. In 6/9 care homes which were represented, there was a policy in place to support CCTV. Administrators described purpose and policy regarding the use of CCTV with the care home. The results were coded using thematic analysis. Three emerging themes were detected from CCTV policy and practice within care homes. These were Patient and Staff Safety and Security, Location & Usage of CCTV, Privacy and Consent for Usage of CCTV.

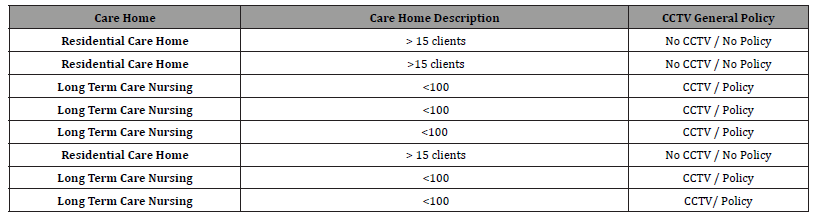

Table 1:Care Home Size and CCTV Policy.

The findings of this research suggested that CCTV was employed within larger care home facilities in Nova Scotia, however smaller group homes or small options home which were administered privately through not-for-profit organizations and did not utilized CCTV. The evidence suggested that within larger homes with a client base of over 15 individuals, CCTV was used for safety and security. Our sample reported use of CCTV within 100% of these the care homes. In smaller care homes that supported less than 15 clients, 0% of homes were equipped with CCTV.

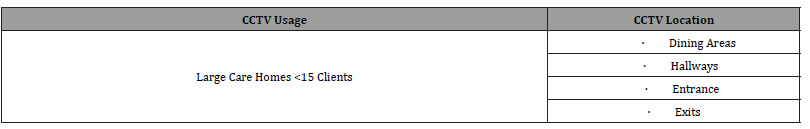

The results indicated that policy was in place for common areas that described usage in hallways, dining areas and most entrance and exit locations. The policy was generally a sign posted within care home entrance area stating that CCV cameras were in use. There was an internal policy at 2 larger care homes which describe no use of CCTV cameras within private quarters such as bedrooms or bathrooms. In some homes, family members have requested Nanny Cam’s within bedrooms, however the policy was stated as a case-by-case basis situation and is very strict. Not all care homes offered a policy of use within private bedrooms.

Table 2:Usage of CCTV with Care Homes.

Staff reported various usage policies for CCTV. As one

administrator of a smaller home with less than 15 clients reported:

“…when I work alone during the night it is hard to be in two

places if I am needed. It would be great to have cameras, but it is

just not an option. Management does not feel it is necessary, and it

is costly they say”

“…when the topic of CCTV is mentioned to the Board of Directors,

there is mixed feelings” stated another home administrator.

When larger home care administrators (serving 20+ clients) completed the interviews, evidence revealed that 100% of respondents stated CCTV was used within the facility for safety and security purpose.

Bobby, a care manager of a home with over 300 residents

posited that CCTV is used within the care home common areas

for client and staff safety. It is used within common areas such as

entrance, exits, hallways, dining areas and recreation areas. It is

not utilized within personal living spaces or client bedrooms. He

explained that:

“…if families request CCTV technology within private

bedrooms there is a very strict policy for usage”.

As Learner [7] noted, the issue of using CCTV in care homes

does raise questions of capacity, consent, and privacy. This was a

challenge within the current study, family members were primarily

the individuals who were providing consent for usage of CCTV

within a care home. Care home administrator Jack, who manages

a larger facility explained supported the use of CCTV for patient

safety through the following dialogue:

“…..CCTV is used at the facility for security purposes and not

for programming purposes. The main areas used for CCTV are

hallways within the common home areas and through the facility

in the dining hall. It is also used in the parking lot area or courtyard

area for example…if in the parking lot area when the guests were

going on a field trip the cameras were able to videotape an accident

where a resident fell and injured themselves, so they used the

footage to protect the clients and to learn from the activity as to

how to prevent it for future outings”.

It was reported that signage was posted at most entrance areas of the larger care homes informing visitors that CCTV was used within the facility. Administrators of small care homes questioned the policy of not having access to CCTV at smaller non-for-profit homes, but larger homes do use the technology. Questions arose about provincial and deferral accountability and access to CCTV to provide enhanced safety and security.

Discussion

This study examined the use of CCTV policy and practice within care home environments in Nova Scotia. Nine care home administrators in Nova Scotia were interviewed about CCTV usage within public and private facilities. A comparison was drawn between policy and usage research in Nova Scotia and the United Kingdom. In this study, it can be noted that larger care home facilities did employ CCTV and the purpose was described for patient and staff safety -security. It was also determined that main areas of use included primarily only common living areas such as hallways, dining areas, entrance and exit areas. The use of CCTC within private or personal spaces was usually not permitted unless requested by family. In those cases, it was determined by management with a rationale and purpose for use.

When comparing the use of CCTV policy within the United Kingdom, Fisk & Flórez-Revuelta [13] noted that technologies do bring benefits, with the right safeguards in place. However, interestingly, within England and Wales, there is no national policy on the usage of CCTV cameras in practices such as care homes. This means that, whilst care homes are to ensure that cameras and other surveillance technologies are to be used effectively and lawfully, what is lacking is one document, rather than different pieces of legislation that guides the usage of CCTV cameras in care homes. Reiterating this confusion caused by a non-existent national legislation, Fisk & Flórez-Revuelta [13] raised the question, on which aspects of camera use should guidelines focus? To answer this, the Care Quality Commission (CQC) offer their advice on the lawful and effective use of CCTV cameras in care homes. Firstly, there must be a legitimate purpose under data protection law for using surveillance This means that, it must be reasonable, lawful, and appropriate.

In Nova Scotia, there were limited policy guidelines from a

Provincial perspective that highlighted CCTV usage within Care

Homes. The Provincial guide brings suggested recommendations

for all operating homes in NS. [11]. Individual care homes are

responsible to develop policy and enforce those guidelines from

within. In the province of Ontario, a recent case was documented

regarding family usage of recordings in resident rooms. As noted by

Pederson, Mancini & Common [14] the camera she gave them was

not allowed because it could record audio. She offered to disable

the audio when she wasn’t interacting with her mom, but the home

said they would only be willing to accommodate a video camera that

couldn’t record audio. Legal obligations surrounding the recording

and privacy of others was stated as rationale. Furthermore, they

state:

“It has been our position that there are legal implications

surrounding the equipment and capabilities that have prevented the

installation,” said Dawn Baldwin, executive director of Extendicare

Lakefield, in an email to Nelson [14].

Conclusion

Today’s ageing populations are associated with increasingly large numbers of people with dementia and complex comorbidities, who are progressively reliant upon residential care home facilities for long-term support. Evidence also indicates that this demographic is growing rapidly in Canada and within the United Kingdom, as well as on a global perspective [11,15] Office of National Statistics, 2014.

Monitoring technologies such as CCTV may be appealing to the care home sector to help enhance safety, increase resident freedom, reduce staff burden, and reduce costs, although robust evidence for their clinical and cost effectiveness is lacking [16]. Our findings elucidate the challenges of care home administration with sizing, policy development and barriers to usage of CCTV. In smaller care homes, the need is not recognized and staff shortages within may be detrimental for clients and staff. Larger homes do recognize the need for CCTV, yet policy isn’t outlined specifically, and administrators feel there can be more explicit direction.

There are thus better opportunities for policy development of CCTV within small and large care homes. In conclusion, CCTV has been utilized as an important tool for safety and security within care homes. There is no consistent policy regarding operation or usage within care homes in Nova Scotia. The main challenges of effective and timely CCTV usage were awareness, communication, and continued policy development. Global policy emphasises the potential of technological innovation to enhance clinical outcomes, economic benefits, and patient experience [17,18].

Such innovation may be particularly appealing for the care home sector given the challenges for safety and security with this fast-growing demographic population [19]. Recommendations for continued research, future policy development of CCTV within care homes, consistent privacy policy development and implementation as well as staff training regarding accurate CCTV policy implementation [20]. A standardized provincial or federal CCTV -Care Home Policy may assist care home administrators with improved safety and security for clients and staff alike.

Acknowledgement

None.

Conflict of interest

No conflict of interest.

References

- Province of Nova Scotia (2017). Shift- Nova Scotia’s action plan for an aging population.

- Klostermann J (2023) Bev said “no”: Learning from nursing home residents about care politics in our aging society. The Gerontologist.

- Gil A (2021) Decent work conditions and quality care: An issue for long-term care policy Ageing & Society 42(9): 126.

- Tufford F, Lowndes R, Struthers J, Chivers S (2018) Call security: Locks, risk, privacy, and autonomy in long -term residential care. Ageing In 43: 34-52.

- Kurdi H (2014) Review of closed-circuit Television (CCTV) techniques for vehicles traffic management.

- Simpson A (2023) Surveillance, CCTV and body-worn cameras in mental health care. Journal of Mental Health 32(2): 369-372.

- Learner S (2013) CQC considers installing CCTV in care homes.

- Manthorpe J, Njoya E, Harris J, Norrie C, Moriarty J (2016) Media reactions to the Panorama programme “Behind Closed Doors: Social Care Exposed” and care staff reflections on publicity of poor practice in the care sector. The Journal of Adult Protection 18(5): 266-276.

- Townsend E (2023) CCTV to be used ‘proactively’ by trusts to combat abuse. Health Service Journal.

- Province of Nova Scotia (2022) Long term care facility requirements.

- Province of Nova Scotia (2022) Census population by age and gender.

- National Health Service UK (2021) Care homes.

- Fisk M, Flórez-Revuelta F (2016) The ethics of using cameras in care homes. Nurs Times 112(10): 12-13.

- Pederson K, Mancini M, Common D (2020) Why some nursing homes won’t let families install ‘granny’ cams to check on their loved ones.

- OECD/European Commission (2013) A Good Life in Old Age? Monitoring and Improving Quality in Long-term Care.

- Hall A, Wilson C B, Stanmore E, Todd C (2017) Implementing monitoring technologies in care homes for people with dementia: A qualitative exploration using Normalization Process Theory. International journal of nursing studies 72: 60-70.

- World Health Organization (2016) Improving Access to Assistive Technology: Document EB139/4.

- Howitt P (2012) Technologies for global health. Lancet 380(9840): 507-535.

- Essén A (2008) The two facets of electronic care surveillance: An exploration of the views of older people who live with monitoring devices. Soc Sci Med 67(1): 128-136.

- Alistair R Niemeijer, Marja F I A Depla, Brenda J M Frederiks, Cees M P M Hertogh (2015) The experiences of people with dementia and intellectual disabilities with surveillance technologies in residential care. Nurs Ethics 22(3): 307-320.

-

Lynn LeVatte*, Ruth Onafuye, Kristin Orourke and Karen Kennedy. Closed-Circuit Television within Residential and Nursing Care Homes in Atlantic Canada: Exploring Policy in the UK and Nova Scotia. Sci J Research & Rev. 3(5): 2023. SJRR.MS.ID.000575.

Care Quality Commission, Nova Scotia, Province of Ontario, Communication, Policy development

-

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.