Research Article

Research Article

High Precision Three-Axis Spacecraft Attitude and Angular Velocity Estimation Through Sequential Pseudo-Linear Kalman Filter Utilizing Extreme Noisy Measurements of a Single-Axis Magnetometer

Tamer Mekky Ahmed Habib*

Research Professor at National Authority for Remote Sensing and Space Sciences, Cairo, Egypt

Tamer Mekky Ahmed Habib, Research Professor at National Authority for Remote Sensing and Space Sciences, Cairo, Egypt

Received Date:April 09, 2025; Published Date:April 25, 2025

Abstract

This paper presents a new approach to estimate spacecraft attitude angles in addition to angular velocity vector based only on magnetometer measurements, even under conditions of high measurement noise and partial sensor failure. Conventional approaches, including those using the Extended Kalman Filter (EKF), encounter major challenges in computational speed and depend on multiple sensors of various kinds to attain complete observability. In contrast, the proposed method reformulates the nonlinear attitude estimation problem into a Pseudo‐ Linear Kalman Filter (PSELIKA) structure and employs a sequential filtering scheme. By processing individual magnetometer measurements one at a time, the proposed algorithm circumvents the need for large matrix inversions and drastically reduces computational complexity. Simulation studies, which use parameters representative of the former Egyptian satellite EGYPTSAT-1 mission, demonstrate that our Sequential Pseudo‐ Linear Kalman Filter (SPSELIKA) converges rapidly even when initial errors are extreme (e.g., up to 170°) and performs well under various scenarios-including full, partial, and single-axis sensor operation. These results indicate that a magnetometer can serve as a stand-alone sensor for both high-precision and low-precision operational modes.

Keywords:Magnetometer; Measurements; Malfunctioning; Sequential Pseudo-Linear Kalman Filter; High Precision

Introduction

There exist several types of spacecraft attitude sensors such as magnetometers, horizon sensors, Sun-Sensor (SS), gyros, …etc. Each sensor type measures certain physical, or environmental quantity in spacecraft Body Coordinate System (BCS). Among these sensors, magnetometers have been used widely as a sensor which forms a backbone for nearly every spacecraft Attitude and Orbit Control System (AOCS). The widespread usage of magnetometers is due to their elongated lifetime, low cost, and minimum electric power consumption. In addition, magnetometers have high reliability. This advantage primarily stems from the fact that magnetometers do not have any internal moving parts. Usually, magnetometers have a measurement channel that measures the earth’s magnetic field vector in each axis of the BCS. Thus, a three-axis magnetometer (TAM) usually contains three channels, corresponding to the three axes of the BCS. Magnetometers can be paired with other spacecraft attitude sensors, as seen in single-frame attitude determination methods [1]. However, this approach presents certain challenges.

For example, Gyros don’t have continuous long operational periods because of error buildup. During the eclipse region of each orbit around the Earth, SS could not provide measurements due to the absence of the sun. Star sensors, while typically offering high-precision attitude data, require substantial electrical power. Given the usual power constraints, star sensors may not be suitable for long-duration operations. Thus, for elongated continuous operational periods, magnetometers represent the only available sensor. Elongated continuous operational periods are encountered during the standby operational mode of the spacecraft. A mode at which the spacecraft spends most of its life time. To keep the spacecraft able to switch from the standby to the high precision modes of operation, spacecraft attitude angles must be coarsely estimated. This process usually requires magnetometer as a sensor that could be used to infer spacecraft attitude angles solely.

Considering all of the aforementioned advantages of magnetometers, numerous high-quality research articles and academic dissertations have rigorously concentrated on estimating spacecraft attitude by means of magnetometer data only. Regrettably, the proposed solutions confront several significant obstacles. This results primarily from several reasons. The first reason is that, the problem of determining spacecraft attitude becomes observable when the spacecraft is fitted with at least two or more distinct types of sensors. Thus, utilizing a sole type of sensors - such as magnetometers- is generally viewed as exceptionally challenging since the system forfeits its complete observability criteria. The issue of system observability worsens when one of TAM channels malfunctions. The issue of system observability reaches its the worst condition when only a single healthy channel of the three TAM channels is available. The next primary reason arises from the careful process of selecting system state representations. Most of the state representations for attitude described in existing literature experience singularities at specific spacecraft orientation angles. This problem could result in complete algorithm blowup, and in critical situation may lead to overall spacecraft mission failure. Thus, representing a barrier to apply numerous algorithms found in the literature.

The third reason arises from the assumption that Euler angles have small values. This assumption limits many algorithms found in the literature to small Euler angles only, making them unable to deal with situations when large Euler angles are encountered. Thus, the many of utilized algorithms during the attitude estimation process could not deal with large estimation errors which are usually encountered during algorithm start-up. The fourth reason is that, for real-time applications, the computational expenses of the estimation algorithm should be kept as minimum as possible. Elongated computation periods during each sampling interval could result in processor hang-up. And in critical electric power reserve conditions this could result in a total mission failure.

To illustrate these challenges, in [2] a TAM is effectively utilized for determining both the spacecraft’s orbit and its attitude. Nevertheless, the newly developed algorithms could only manage relatively small initial attitude estimation errors limited to 16 degrees. In Ref. [3], the spacecraft’s attitude was determined exclusively from magnetometer readings. But the developed algorithm could deal with a maximum of 45 degrees angular estimation error at algorithm startup. In [4], several comprehensive spacecraft attitude estimation models were thoroughly outlined. Ref. [5], stated that several attitude determination methods are rarely utilized because of their high computational demands. These high computational demands could prevent real time application of such algorithms. This is due to the fact that many currently commercially active spacecrafts still operate using processors that are typically dates fifteen to even twenty years back [6]. Algorithms like those presented in [7] might not be deployable on a processor twenty years old. In addition, the Extended Kalman Filter (EKF) adopted in this reference requires intensive computations by the On- Board Computer (OBC) of the spacecraft due to the need to go through matrix inversion process.

Ref. [8] reviews several methodologies of estimating attitude angles of a spacecraft via SS, and TAM without gyro measurements incorporated. Ref. [9] provided estimates of spacecraft attitude representing parameters based on TAM, and SS. The developed algorithms could deal with maximum initial estimation angular error of 60 degrees. The developed estimation algorithm in [10] reached a steady-state error of about 14 degrees in the yaw angle utilizing TAM measurements. [11] utilized magnetometer measurements to estimate only the yaw angle of the spacecraft. In Ref. [12], the spacecraft attitude problem was linearized. The linearly estimated spacecraft attitude is computed utilizing TAM measurements. The provided estimates exhibit a relatively large steady- state values of the error which reached about 3 degrees. Ref [13], developed algorithms to estimate spacecraft attitude within an accuracy of 0.3 degrees via Unscented Kalman Filter (USKF) of magnetometer measurements. But it is well known that USKF relieves totally any linearization, or small angle approximation assumption by means of propagating a fixed set of sigma-points. This process results in higher accuracies with increases computational expenses. Ref. [22] employed an USKF to obtain estimates of spacecraft position, and velocity through a linear system.

Primarily, this study’s main objective and contribution is to introduce a spacecraft attitude estimation method that relies solely on measurements of a magnetometer. This innovative method successfully addresses all of the previously mentioned challenges detailed in the comprehensive literature review, concurrently and efficiently. The method presented in this study employs the Sequential Pseudo Linear Kalman Filter (SPSELIKA), specifically developed to address the matrix inversion issue linked to traditional KF or EKF based algorithms. The proposed method is based on further improvement of the standard Pseudo Linear Kalman Filter (PSELIKA). In doing so, the method boosts computational speed and performance for real-time applications. Furthermore, this proposed method is benchmarked against validated EKF-based algorithms including PSELIKA those were used to determine attitude angles of the earlier Satellite, EGYPTSAT-1, confirming the efficiency of the proposed method. The current manuscript is arranged as follows: Section 2 describes spacecraft angular motion kinematics, and dynamics along with nonlinear motion models governing the spacecraft translational movement. Section 3 details the development of the pseudo‐ linear filtering approach, including its sequential update formulation and observability analysis. In section 4, simulation environment is setup and performance of the SPSELIKA algorithm under different sensor configurations is assessed. Finally, Section 5 summarizes the key contributions and suggests a future work plan.

Nonlinear spacecraft motion models

To continue, it is necessary to provide clear definitions for the frames of reference that are to be used. The first fundamental frame is the inertial frame of reference. This frame of reference has its center coinciding with the earth center. It features an X-axis pointing to direction of the Vernal Equinox, a Z-axis pointing in the same direction of the Earth’s rotation about itself. The Y-axis of the inertial frame of reference satisfies a right-hand rule. A Reference Coordinate System (RCS) is also defined. Within RCS, an X-axis is defined as coinciding with the velocity vector of the spacecraft. A Z-axis coinciding with Nadir direction is chosen. The remaining Y-axis completes a right-hand triad rule. The RCS of the spacecraft coincides with its BCS in case of zero values of the attitude angles (yaw, pitch, and roll angles).

Using Cowell’s formulation [21], the translational motion is described as [4]:

Within the inertial frame of reference, the position vector of the spacecraft’s is denoted as RI , the over symbol double dot denotes its second time derivative. The Earth has a gravitational constant is denoted as μE . The symbol aa corresponds to perturbing acceleration due to Earth’s asphericity (see [15] for calculation procedures).

The governing equations describing a spacecraft’s attitude motion is thoroughly elucidated solely by the particular kinematic, and dynamic equations explicitly referenced in [16, 23]. The spacecraft kinematic equations could be expressed in a matrix form as

Symbol over dot indicates the first derivative w.r.t time. A vector

can be converted from the inertial reference frame to the body axes through the quaternion vector,

,which consists of imaginary

components, q12 and q3 , and a real part, q4 . The equation

that specifies the matrix, designated as ∃ , can be written as

,which consists of imaginary

components, q12 and q3 , and a real part, q4 . The equation

that specifies the matrix, designated as ∃ , can be written as

And, represents the vector of spacecraft inertial

angular velocities. The rotational dynamics of the spacecraft

could be described according to [16].

represents the vector of spacecraft inertial

angular velocities. The rotational dynamics of the spacecraft

could be described according to [16].

with Ta,Tg,Ts,Tr, denoting respectively moments generated by aerodynamic forces, gravity gradient, solar pressure, and residual magnetic effects. H denotes the angular momentum vector of any inner moving components. wk stands for a white Gaussian zero-mean noise corresponding to the process noise. Details for calculating disturbance moments can be found in [15]. [η ×] is a matrix form of the vector η=[ηxηyηz] defined as

With the definition related to inertia matrix of the spacecraft’s, J , as

Selecting the state vector which describes a spacecraft’s attitude motion is crucial, serving as a vital element for any spacecraft attitude estimation technique. Thus, the spacecraft representing state vector is chosen as demonstrated above and confirmed through analysis to be

The state vector representing spacecraft attitude (rotational) motion defined by equation (7) enables a singularity-free representation of the attitude angles, thus effectively preventing algorithm blow-up resulting from singularities. Furthermore, it allows accurate depiction of spacecraft maneuvers involving large Euler angles. In addition, choosing the spacecraft orbital motion state vector, as shown in equation (1), ensures that no singularities ever occur in the simulation for particular orbit types.

Attitude estimation

The main responsibility of any estimation algorithm is to compute the state estimate of a plant subject to un-modelled random disturbance with maximum accuracy, utilizing sensors subject to measurement errors. Techniques that utilize Singular Value Decomposition (SVD) usually are unfavorable due to their substantial computational expense [5]. This is because of the severely restrictI ed processing power available on board a spacecraft in orbit. Consequently, algorithms based on EKF have been extensively employed due to their remarkable performance in diverse situations in orbit. A highly efficient real-time algorithm can be formulated Using EKF could be framed as will be described in sections 3.1, and 3.2.

Pseudo-linear Kalman Filter (PSELIKA)

Nonlinearities in either the measurements or the plant dynamics or both necessitates the use of EKF [2]. PSELIKA can be considered a straightforward ad-hoc variant of EKF. In terms of structural components, PSELIKA closely resembles the EKF. The nonlinear system describing equations are factored as.

Where (xˆ)(-),(xˆ)(+) and are a priori, and posteriori state estimate respectively. Additionally, the measurement process is also described by.

Where is the actual state vector The matrices  could be computed as follows: first the magnetic field vector of the

earth, BB , satisfies the relation:

could be computed as follows: first the magnetic field vector of the

earth, BB , satisfies the relation:

With, BI, is defined as the vector of the earth’s magnetic field expressed in the inertial frame of reference,

Equation (8) casts a nonlinear function into a linear-like form. This is because of that the matrix, Ψk−1 , is dependent on the preselected state vector. Thus, PSELIKA algorithm behaves like an adhock algorithm. Finally, the matrix, Ck , is defined as

The a priori covariance matrix of the estimation error, Pk(−), could be computed from

And, Qk−1 , is the discrete process noise covariance matrix. The measurement update phase is represented by

Considering that the discrete measurement noise covariance matrix, ℜk , is related to its counterpart continuous form, ℜ(t) , via the relation [18]

With ΔT defined as the sampling time. Likewise, , Qk , could be computed from its continuous counterpart form Q(t) , by [19].

And, β denotes the time variable.

The proposed Sequential Pseudo-linear Kalman Filter (SPSELIKA) structure

Sometimes, the standard (EKF) is labeled as “batch EKF” since it batches all measurements at every time interval entirely. Nonetheless, embedded systems might experience complications with the batch EKF because it demands inversion of a square matrix whose size is matching the measurement process covariance matrix size. Thus, an innovative approach of sequential processing is presented in [17] for practical applications to overcome this problem. This is because of that as the measurement vector size increases, the matrix inversion problem becomes more complicated to be implemented in real-time. Using SPSELIKA, the measurement vector is separated into elements that are input independently to resolve the previously mentioned issue. By this means, filter performance in terms of computational requirements is enhanced. Thus,

With zj,k stands for the measurement vector element j (j =1, 2,....., N), and, N, denotes the measurement vector length. Cj,k : row number (j) of the measurement matrix, Ck .

Filter algorithm proceeds as follows

The preceding formulation of SPSELIKA presumes that, ℜk, is a diagonal matrix.

Analyzing system observability

Observability of the proposed SPSELIKA algorithm could be analyzed via Floquet theory [3]. Thus, we could formulate the matrix, Φ , as

Where IM×M , is an identity matrix of order M, and M is the state vector size. Every eigenvalue of, Φ , is required to be less than one within the SPSELIKA steady-state regime to ensure that the estimator remains stable. Moreover, the remarkably small maximum eigenvalue directly indicates a good convergence rate.

Simulation parameters, results, and discussions

The SPSELIKA algorithm developed in the current study was benchmarked against previously validated EKF-based algorithms [24-25] designed for the EGYPTSAT-1 spacecraft, which had an epoch of 17 April 2007 00:00:00. EGYPTSAT-1 spacecraft was owned, and managed by the National Authority for Remote Sensing and Space Sciences (NARSS). The parameters of EGYPTSAT-1 are extracted from design simulations conducted throughout various phases of spacecraft design. These values were provided in [14]. Moreover, a validated EKF algorithm was formulated and examined in [4,14]. EGYPTSAT-1 featured a semi- major axis equal to 7039200 meters, an eccentricity equal to 0, an orbital inclination equal to 98.085 degrees, an argument of perigee that equals 69 degrees, a true anomaly equal to 0 degrees, and a right ascension of the ascending node equal to 337.5 degrees.

The spacecraft’s epoch time was set to 17 April 2007 at 00:00:00. The actual starting attitude angles were -165 degrees for yaw, 170 degrees for roll, and 85 degrees for pitch. Furthermore, the initial angular rates for the spacecraft’s attitude were 0.7 o/s, 0.8 o/s for roll, and -0.2 o/s for pitch. Both EKF-based algorithms, and SPSELIKA algorithms start with initial values of zero. This indicates that no initial data about the attitude angles is available, which is generally true when EGYPTSAT-1 was operating in the detumbling operational mode just after launch. The algorithm uses a sampling time of 4 seconds. TAM standard deviation errors were 200 nT for each axis. and this value is regarded as a particularly very high. Furthermore, a maximum estimation error of ± 5 degrees is allowed for low- precision operational modes and about ± 0.5 degrees for high-precision operational modes of each spacecraft body axis.

The first scenario (All of the channels of TAM are functioning)

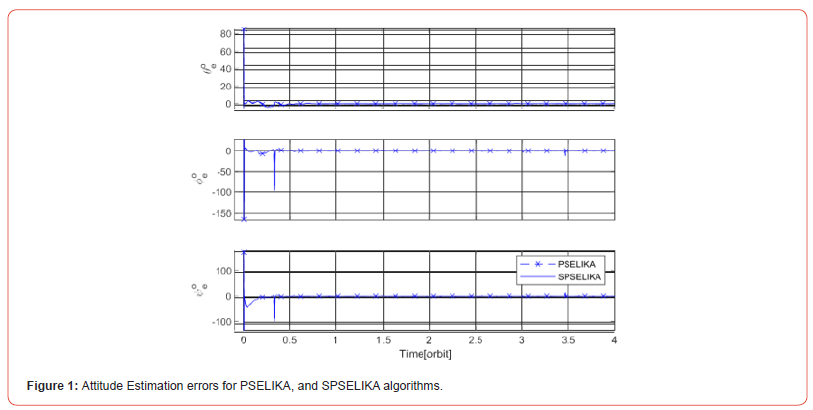

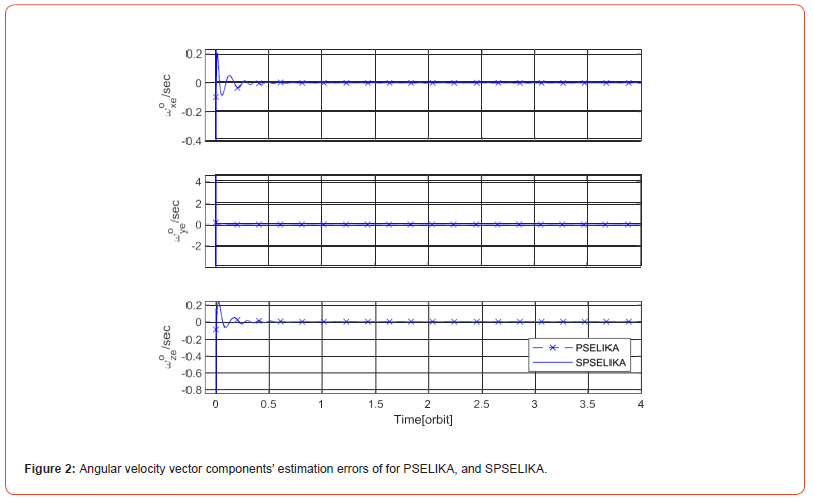

In this scenario, we are analyzing data from the three channels of a TAM. Figure 1 clearly illustrates the time evolution of attitude estimation errors, whereas Figure 2 accurately portrays the estimation error in each angular velocity vector component. As shown in Figures 1 and 2, estimation errors resulting from both the PSELIKA and SPSELIKA overlap exactly. This demonstrates equivalent accuracy performance. Furthermore, both figures clearly reveal that the filter consistently attains a fully steady-state operation after just half of an orbital period. This significant accomplishment is truly remarkable, as both the PSELIKA and SPSELIKA algorithms reliably and consistently converge even when facing substantial estimation errors-up to 170 and 85 degrees respectively-that are frequently corresponding to the spacecraft detumbling operation mode. Consequently, the newly developed SPSELIKA algorithm is extremely flexible and can be seamlessly deployed across any spacecraft operational mode, either having low or high precision requirements.

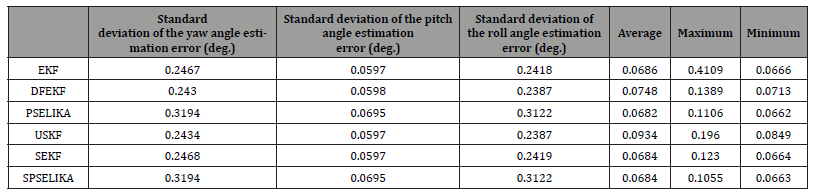

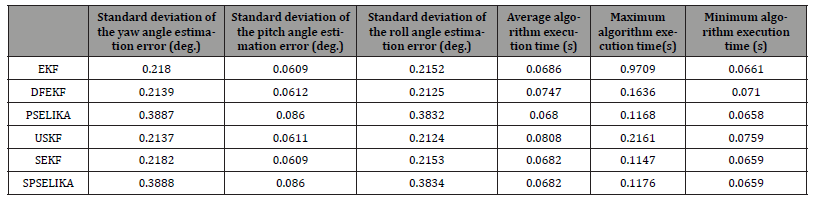

Computations are carried out on a personal computer outfitted with a CPU having a processing speed of 3.4 GHz along with 8 GB of RAM. The obtained precision and execution time of the developed SPSELIKA algorithm is presented in Table1. Table 1 shows that both the PSELIKA and SPSELIKA exhibit an exceptionally low values of the estimation error standard deviation compared to the permitted angular error. This happens despite of the fact that measurement errors of the magnetometer are 200 nT, which is much higher than those given in the other studies (typical value in these studies ranges between 50 to 100 nT). Due to the obtained accuracy, a TAM can function solely to provide attitude estimates throughout all spacecraft modes of operation, without requiring any other types of sensors.

Table 1:Core performance evaluation metrics.

average execution time shown in Table 1 exhibits nearly identical values, whereas the maximum execution time differs indeed. The maximum execution time is widely deemed extremely critical for real-time applications to the OBC. This is because of that, at every single time step, the OBC consistently enforces a stringent calculation time boundary to execute any function so as to avoid the OBC hang up. Therefore, exceeding this time boundary may result in OBC shut down or a complete spacecraft restart to prevent endless hang up. This may result in a severe problem if the spacecraft lacks sufficient electrical power to restart, potentially resulting in a complete mission failure. The algorithms used for benchmarking are EKF, Derivative Free form of EKF (DFEKF), the Unscented Kalman Filter (USKF), and finally the Sequential EKF (SEKF). The developed SPSELIKA algorithm achieves the least execution time among all of the benchmarking algorithms. Which could be considered as a marked improvement.

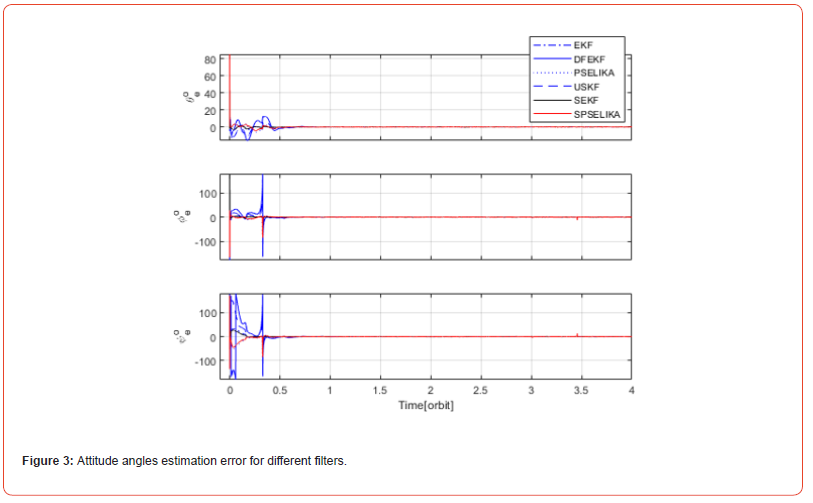

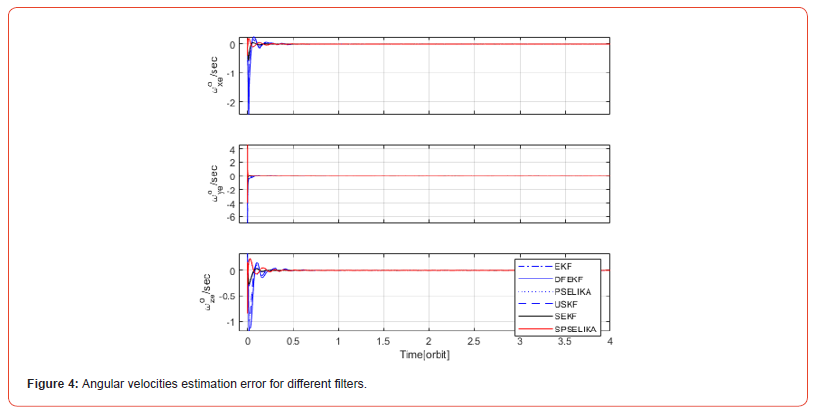

Figure 3, compares attitude estimation errors of SPSELIKA algorithm with other benchmarking algorithms. Figure 4, compares angular velocity components’ estimation errors for the proposed algorithm of SPSELIKA with other benchmarking algorithms. Figures 3, and 4, shows nearly an identical performance in the steady state region (i.e. after 1 orbit). Ref. [20] presented the αβ filter. In addition, a comparison is made between this filter and EKF. Both filters were calculated via a personal computer. The αβ filter execution time was 0.39 s. EKF needed 0.74 s to complete. SPSELIKA measured execution time was 0.0663 s. This shows the improved SPSELIKA performance. Moreover, the formulation of SPSELIKA does not assume any approximations related to small Euler angles. This allowed SPSELIKA to be able to converge despite huge initial estimation errors encountered.

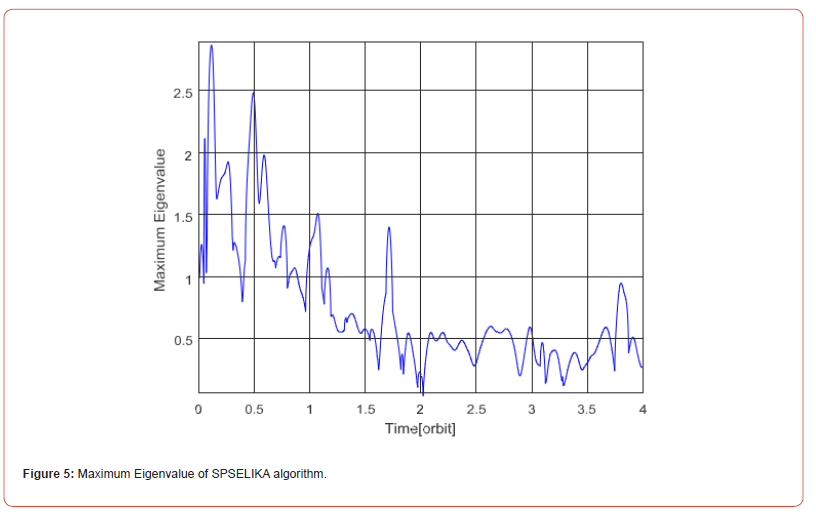

Figure 5 shows the maximum eigenvalue of the matrix, Φ , for

SPSELIKA algorithm. The magnitude of the maximum Eigenvalue

drops below one. This indicates an enhanced convergence rate and

ensures system observability when relying on TAM solely for attitude

estimation. Based on Table 1, and Figure 1 to 5, SPSELIKA algorithm

have the following advantages relative to other algorithms

found in the literature:

1. Convergence of the estimation error to very low values compared

to the required accuracy level despite large initial estimation

errors.

2. Reduced levels of attitude estimation errors (achieving a standard

deviation of 0.32 degrees) in comparison to the maximum

allowable error, which is preset at ± 0.5 degrees.

3. Reduced execution time compared to other Kalman Filter

based algorithms.

The second scenario (Two channels of TAM are functioning)

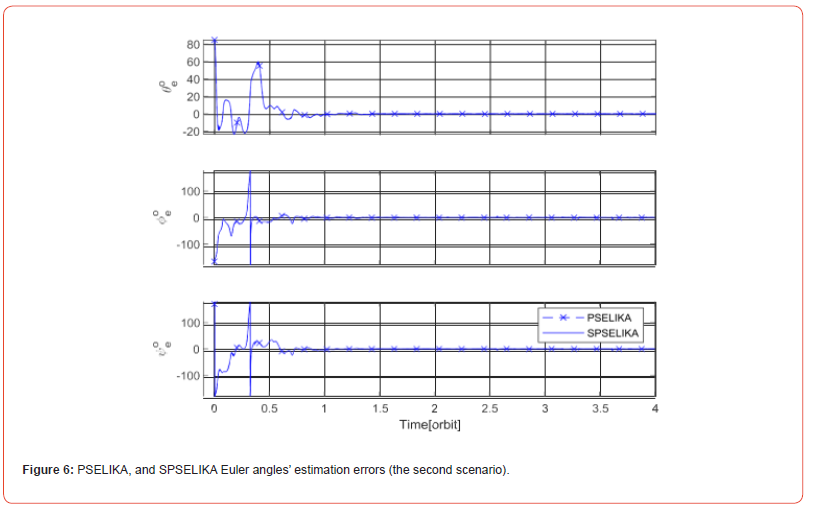

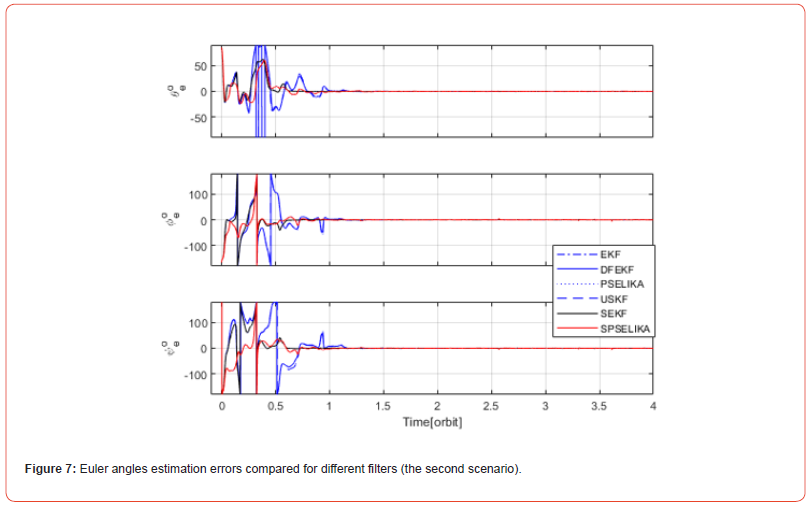

The second scenario depends of the same spacecraft parameters as the first scenario. Measurements of the x, and y channels of the TAM are the only available measurements due to the malfunction of the z channel. Figure 6 displays the time evolution of EGYPTSAT-1 Euler angles’ estimation error with a faulty z channel. As clarified in figure 6, the curves of both SPSELIKA, and PSELIKA are nearly identical. This obviously demonstrates that both filters have equivalent accuracy. Furthermore, both SPSELIKA and, PSELIKA reach steady state operation after one and half orbital periods, which is a bit more than that observed in the first scenario. This is due to the fact that only two measurements, out of three are available. Consequently, SPSELIKA, and PSELIKA need extra operational time in addition to more sampled measurements to converge successfully. Figure 7, compares estimation error of SPSELIKA with other EKF-based algorithms. As clarified in this figure, after 1.5 orbits, the attitude estimation error is nearly identical for all of the attitude estimation algorithms.

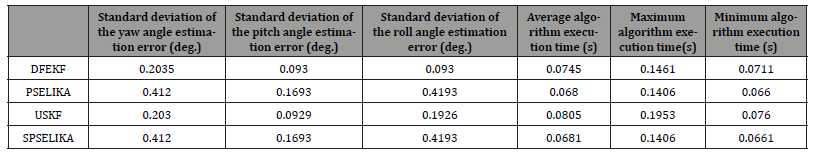

Table 2 lists the core performance evaluation metrics of SPSELIKA against other EKF- based algorithms with a malfunctioning z-channel of TAM. The steady-state Euler angles estimator errors encountered are marginally somewhat larger than what typically encountered in the first scenario due to the availability of only two measurement channels. The main purpose of developing SPSELIKA is to reduce computational time through introducing scalar measurements sequentially rather than as a batch. Thus, as the number of the available measurements is reduced from three measurements in the first scenario to only two measurements in the second scenario, the difference between SPSELIKA, and PSELIKA estimation algorithms is reduced. Or alternatively, as the number of simultaneous accessible measurements increases, the performance of the proposed SPSELIKA is enhanced. This is due to the fact that SPSELIKA avoids matrix inversion processes associated with the rest of benchmarking algorithms.

Table 2:Core performance evaluation metrics.

The third scenario (A single channel of TAM is functioning)

The third scenario, has the same spacecraft parameters as the first, and second scenarios. Measurements of the x channel of the TAM are the only available measurements due to the malfunction of the remaining channels. Figure 8 displays Euler angles’ estimation errors when only measurements of the x-axis channel of the magnetometer is functioning. As shown in Figure 8, Euler angles estimation errors of SPSELIKA, and PSELIKA are nearly identical. This result confirms equivalent accuracy levels for both filters. Figure 8, shows also that both filters reached the steady state operational region after 6 orbits which is considerably larger than the results we obtained in the first and second scenarios. Again, this is primarily due to the reduction in the number of measurements available to only a single measurement instead of three measurements..

Table 3:Core performance evaluation metrics.

Table 3 shows core performance evaluation metrics for the SPSELIKA against other functioning EKF-based algorithms when only measurements of the TAM x-channel are available. The obtained levels of steady state estimation errors in the third scenario are higher than those of the first, and second scenarios due to the reduced number of simultaneously available measurements. We could also note that estimation errors in the third scenario, is still below the prescribed ± 0.5 degrees range. Thus, the developed SPSELIKA algorithm is still able to converge to acceptable levels despite having only a single functioning TAM channel. Due to reduction of the number of simultaneous measurements to a scalar value instead of a vector, both SPSELIKA, and PSELIKA need the same calculation resources. Thus, the execution time is nearly identical in both cases. Finally, despite having only a single functioning channel, the developed SPSELIKA algorithm is still able to deliver attitude estimates within the prescribed high accuracy demands of the spacecraft operational modes.

Conclusion and Future Work

Within this article, a method is formulated to effectively estimate spacecraft quaternion vector in addition to angular velocities relying only on magnetometer measurements. This method employed a SPSELIKA formulation and was benchmarked against validated EKF-based algorithms. The SPSELIKA approach matched the PSELIKA in accuracy while offering a faster algorithm execution time. The developed SPSELIKA algorithm achieved an accuracy of at least 0.42 degrees for each axis, enabling its use without supplementary sensors. The process avoided small angle approximations by representing the spacecraft attitude with a quaternion vector, thereby circumventing singularity issues associated with large attitude angles. The SPSELIKA method proved capable of converging even when faced with initially large estimation errors of Euler angles reaching 170 degrees, and 0.8 o/s for the inertial angular velocities. The performance of SPSELIKA algorithm was assessed via Floquet theory, demonstrating excellent observability in addition to rapid convergence rate. Furthermore, the method continued to yield highly accurate attitude estimates when the magnetometer’s z-channel failed. When only the TAM x-channel is functioning, the proposed SPSELIKA algorithm is still able to deliver adequate attitude estimates characterized by high precision.

NARSS plans to build a spacecraft for earth observation purposes. Consequently, this spacecraft name is suggested as NARSS Earth Observation satellite (NEOSat-1). A Future proposed work is scheduled to apply the established SPSELIKA algorithm to a Hardware In the Loop Simulator (HIL) environment. Thus, the plan is to deploy the developed SPSELIKA algorithms on an actual spacecraft mission initially as backup solutions in NEOSat-1. In a next stage, the proposed SPSELIKA algorithm is planned to serve as a main source for providing attitude estimates.

Acknowledgements

The Author declares that this research is funded by NARSS under project code 0785/SR/SPA/2025. Online Journal of Robotics & Automation Technology fully supported open access publication of the current research article.

Declarations

Conflict of interest:

The author affirms that there are no additional financial interests associated with the research presented in this manuscript.

Declaration of generative AI and AI-assisted technologies in the writing process

During the preparation of this work the author(s) used deepseek, and ChatGPT in order to improve language and readability. After using deepseek, and ChatGPT, the author reviewed and edited the content as needed and takes full responsibility for the content of the publication.

References

- Guler D, Conguroglu E, Hajiyev C (2017) Single-Frame Attitude Determination Methods for Nano-Satellites, Metrology and Measurement Systems 24(2): 313-324.

- Deutschmann J, Itzhack Y Bar Itzhack (2001) valuation of Attitude and Orbit Estimation Using Actual Earth Magnetic Field Data, Journal of Guidance Control and Dynamics 24(3): 616-623.

- Psiaki M, Martel F, Pal P (1990) Three-Axis Attitude Determination via Kalman Filtering of Magnetometer Dat, Journal of Guidance Control and Dynamics 13(3): 506-514.

- Habib T (2009) New Algorithms of Nonlinear Spacecraft Attitude Control via Attitude, Angular velocity, and Orbit Estimation Based on the Earth's Magnetic Field, PhD Thesis, Cairo University.

- Markley FL, Mortari D (2000) Quaternion attitude estimation using vector observations, Journal of the Astronautical Sciences 48(2): 359-380.

- Habib T (2022) Spacecraft Attitude and Orbit Determination from the Cost and Reliability Viewpoint: A Revie, ASRIC Journal on Natural Sciences, pp. 14-35.

- Guler D, Conguroglu E, Hajiyev C (2022) Attitude and Gyro Bias Estimation by SVD-aided EK, Measurement Vol. 205.

- Guler D, Hajiyev C (2016) Review on Gyroless Attitude Determination Methods for Small Satellites, Progress in Aerospace Sciences 90: 54-66.

- Bak T (1999) Spacecraft Attitude Determination- a Magnetometer Approac, PhD Thesis, Department of Control Engineering, Aalborg University,

- Carletta S, Teofilatto P, Farissi M (2020) A Magnetometer-Only Attitude Determination Strategy for Small Satellites: Design of the Algorithm and Hardware-in-the-Loop Testin, Aerospace, pp. 1-21.

- Hart C, Teofilatto P, Farissi M (2009) Satellite Attitude Determination Using Magnetometer Data Only, 47th AIAA Aerospace Sciences Meeting Including the New Horizons Forum and Aerospace Exposition, pp 1-11.

- Han K, Wang H, Jin Z, Teofilatto P, Farissi M (2010) Magnetometer-Only Linear Attitude Estimation for Bias Momentum Pico-Satellit, Appl. Phys. & Eng 11(6): pp 455-464.

- Hart C, Teofilatto P, Farissi M (2005) Unscented Kalman Filter for Spacecraft Attitude Estimation and Calibration Using Magnetometer Measurement, Proceedings of the Fourth International Conference on Machine Learning and Cybernetics, pp 18-21.

- Habib T (2013) A Comparative Study of Spacecraft Attitude Determination and Estimation Algorithms (A cost-benefit approach), Aerospace Science and Technology 26(1): pp 211-215.

- Habib T, (2022) Artificial Intelligence for Spacecraft Guidance, Navigation, and Control: A state-of-the-art, Aerospace Systems 5: 503-521.

- Sidi M J (1997) Spacecraft Dynamics and Control, a Practical Engineering Approach, Cambridge University

- Simon D (2006) Optimal State Estimation, Kalman H, and Nonlinear Approaches, John Wiley and Sons pp. 150.

- Brown R G, Hwang P Y (1997) Introduction to Random Signals and Applied Kalman Filtering, John Wiley and Sons, Inc. Page 290-291.

- Smyth A, Wu M (2007) Multi-rate Kalman filtering for the data fusion of displacement and acceleration response measurements in dynamic system monitoring, Mechanical Systems and Signal Processing 21: 706-723.

- Halima B (2022) A Combined Configuration (αβ filter- TRIAD algorithm) for Spacecraft Attitude Estimation based on in-Orbit Flight Data, Aerospace systems 5: 223-230.

- Srivastava V, Mishra P, Ramakrishna B (2021) Satellite Ephemeris Prediction for the Earth Orbiting Satellites, Aerospace Systems 4: 323-334.

- Driedger M, Rososhansky M, Ferguson P (2020) Unscented Kalman Filter-Based Method for Spacecraft Navigation using Resident Space Objects, Aerospace Systems 3: 197-205.

- Fu J, Chen L, Zhang D, Shao X (2022) Orbit–Attitude Dynamics and Control of Spacecraft Hovering Over a Captured Asteroid in the Earth–Moon System, Aerospace Systems 5: 265-275.

- Habib T (2023) Three-axis High-Accuracy Spacecraft Attitude Estimation via Sequential Extended Kalman Filtering of Single-Axis Magnetometer Measurements, Aerospace Systems.

- Habib T (2023) Magnetometer-Only Kalman Filter Based Algorithms for High Accuracy Spacecraft Attitude Estimation (A Comparative Analysis), International Journal of Robotics and Control Systems 3: 433-448.

-

Tamer Mekky Ahmed Habib*. High Precision Three-Axis Spacecraft Attitude and Angular Velocity Estimation Through Sequential Pseudo-Linear Kalman Filter Utilizing Extreme Noisy Measurements of a Single-Axis Magnetometer. On Journ of Robotics & Autom. 3(5): 2025. OJRAT.MS.ID.000572.

Magnetometer; Measurements; Malfunctioning; Sequential Pseudo-Linear Kalman Filter; High Precision

-

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.

- Abstract

- Introduction

- Precision, Efficiency, and Collaborative Robotics (Cobotics)

- Energy Conservation and Green New Work

- Flexibilization of the workplace and ecological benefits

- Waste reduction, circular economy, and cobotic synergy

- Reduction of Harmful Emissions

- Challenges and Considerations

- Conclusion

- Acknowledgement

- Conflict of Interest

- References