Review Article

Review Article

Dynamic System Modeling for Flexible Structures

Trevor Bihl1* and Timothy Sands2

1College of Engineering and Computer Sciences (CECS), Marshall University, Huntington, WV, USA

2Sibley School of Mechanical and Aerospace Engineering, Cornell University, Ithaca, NY, USA

Trevor Bihl, College of Engineering and Computer Sciences (CECS), Marshall University, Huntington, WV, USA

Received Date:August 21, 2024; Published Date:October 02, 2024

Abstract

With the increasing use of robotics for commercial, industrial, and residential use, reliable control is needed. Many such applications, applications ranging from space missions to architectural design to aerospace, include large flexible structures. However, the interaction between a control system and a structure’s dynamics can significantly degrade system performance due to mismodeling, especially of flexible modes of interest is thus accurate models of the system to facilitate control. For such modeling, approaches generally fall into one of four groups: (1) kinematics and dynamics estimate, (2) Finite element analysis, (3) System identification, and (4) Adaptive systems. This paper provides a review of these approaches as well as a synthesis on an end-to-end use of these methods.

Introduction

Modeling and control of large flexible structures is increasingly needed in many applications such as space missions, architectural design, and aerospace applications. Flexible structure analysis is not limited to aerospace applications. Structures such as skyscrapers and cellular phone towers often pose many structural challenges such as the effects of wind-induced vibrations, which in severe circumstances can damage or destroy a structure [1]. Counteracting these effects is possible with various active and passive damping methods [1]. Properly handling these vibrations requires an accurate model to design a controller that can damp vibrations and/or appropriate passive damping methods.

The interaction between a control system and a structure’s dynamics can significantly degrade the overall system’s performance due to mismodeling, especially of flexible modes. Such errors can cause inaccuracies in positioning for spacecraft [2] or catastrophic failures in physical structures [3]. In systems involving active and passive control of structures, effective controller design required accurate models that include the various modes of the structure.

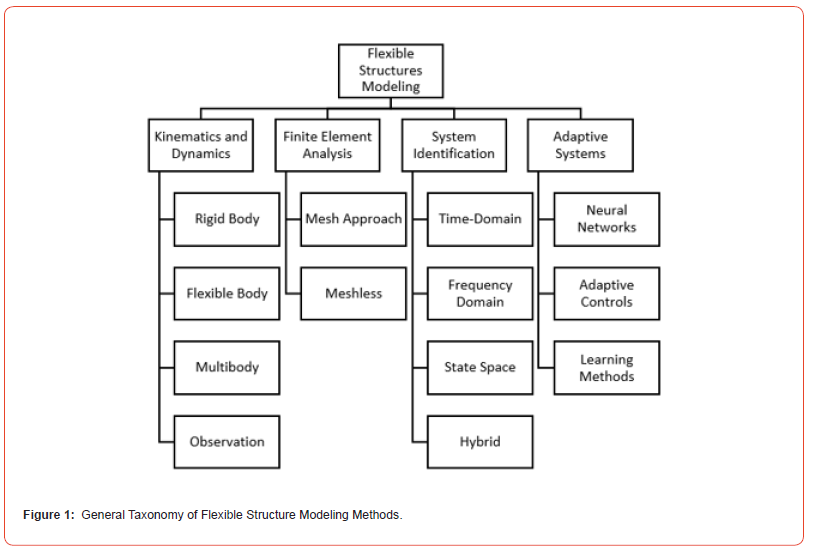

Of interest herein is a review of methods used to create flexible structure models. A general taxonomy of such methods is presented in Figure 1. Typically, there are three methods primarily used to develop linear mathematical models of dynamical systems for controller development, (1) using kinematics and dynamics methods for analysis, (2) finite element analysis, and (3) system identification. However, a fourth method, (4) adaptive systems, approaches the problem from a real time approach. This review covers the extent of these methods, as well as concluding on an ideal end-to-end design and control approach.

Dynamics and kinematics estimation

Dynamics and kinematics methods are employed by modeling the known forces and moments acting upon a structure, and then using this model to predict the behavior of the actual system [4,5]. Collectively, such approaches are well known, and grounded in classical statics and dynamics, but susceptible to inaccuracies from mismodeling and unanticipated real-world conditions [4]. However, these approaches are extremely important and useful in anticipating behavior of a dynamical system during preliminary design and prototyping stages whereby simulation and design configurations and can be rapidly explored [6].

These approaches generally fall into 1) classical kinematics and dynamics whereby a system is decomposed into known parts with the respective forces and moments characterized [7]. Extending from there, 2) flexible body considerations are possibly included by taking into account more material property considerations [8]; notably, taking such approaches further often moves towards finite element analysis. And finally, 3) multibody modeling of complex structures [9]. Beyond these traditional methods, new approaches to dynamics and kinematics estimation are being explored through 4) observation-based methods. Here, video or pictures of an object are used to estimate the kinematics of the system [10]. This concept of modeling extends from computer vision work in pose estimation [11] and object detection/segmentation [12].

Finite element analysis

Finite element analysis is a numerical analysis method that models a structure by assembling individual structural elements connected together at various points, called nodes [13,14]. Such approaches typically extend the concepts of dynamics and kinematics models through refined understanding of the material properties of each element as well as considering objects as a system of nodes, called a mesh, to simulate the structure [13,14]. Extensions of this approach include handling discontinuities which result in poorly developed models. One dominant approach includes meshless methods which generally solve partial differential equations (PDEs) without relying on a predefined mesh or grid, which is typical in traditional methods like the Finite Element Analysis [15].

Instead of using a mesh to discretize the problem domain, meshless methods represent the domain using a set of points or particles, allowing for greater flexibility in handling problems with large deformations, complex geometries, or evolving boundaries. However, despite many advances, models developed with kinematics and dynamics methods and finite element analysis methods both typically experience significant initial inaccuracies (due to errors from approximations, mismodeling, and incorrect assumptions) and thus typically require refining the model using experimental data [13].

System Identification

System identification develops a mathematical model of a system based upon input/output data [16]. Thus, a heavy burden typically placed on proper sensor selection and placement, input signal design [17], data collection [18], and appropriate/acceptable estimated model order [16,19], [20-22]. Generically, system ID processes work by creating an analytical model of a system, estimating the system’s modal and excitation characteristics, determining sensor and actuator locations and requirements, exciting the system to collect experimental data, using a system ID method (such as mentioned above) on the data to create a model, and then refining the analytical model based on experimental results [13].

System identification methods are generally broken into 1) time domain-based methods, 2) frequency domain methods, 3) state space methods, and 4) hybrid and other approaches. These categories depend on how data is processed and the underlying methods used. Collectively, system identification methods have routinely focused extracting models from noisy data [23] [13, 24] (Mitchell et al., 2007).

Time domain system identification methods typically extend least squares methods (such as for single-input, single-output systems (SISO)) or state space system ID methods, for SISO, SIMO (single-input, multiple-output), and/or multiple-input, multipleoutput (MIMO) systems [13] [24]. Frequency domain system identification, on the other hand, often employes transfer function approaches [13]. State space system identification employs state space modeling approaches, such as seen in the Eigensystem Realization Algorithm (ERA) [25].

Since state space methods are often orders of magnitude higher than needed, often due to noisy impulse response data, hybrid approaches that combine frequency domain and state space methods are often of interest [24] Other directions in system identification include nonlinear methods [26], employing neural networks [27, 28], and using other machine learning methods [29].

Adaptive Systems

Methods termed herein as “adaptive systems” consider the problem as first a general understanding of the dynamics and controls needed for a system and then apply a learning system to quickly accommodate perturbances and changes. One such system is the spiking neural network approach of DeWolf et al. [30] which models the overall control of a system as by a cognitive architecture similar to a biological brain. This system adapts to unknown changes in arm dynamics and kinematic structure similar to how a biological brain would adapt to picking up an object.

Synthesis

This review covered the scope of families of approaches used for modeling of flexible structures with the end goal of controlling such a structure. Thus, we covered the methods of 1) kinematics and dynamics estimates, 2) finite element analysis, 3) system identification, and 4) adaptive systems. However, by themselves each approach is useful in only part of a process in controlling a structure with flexible components. Ideally, an end-to-end use of these methods would involve all of these approaches used in a systematic way.

The overall use would be to begin by designing a system and develop as accurate as possible dynamics and kinematics models to describe expected motions and deformations. From here one would naturally apply finite element analysis to numerically solve the equations derived from the dynamics and kinematics models. When the system is constructed and in use, system identification would come into play to validate and refine the finite element models using experimental data, ensuring they accurately reflect the physical system. As an outer loop on this system, an adaptive system could be incorporated to enhance modeling accuracy and provide real-time prediction capabilities.

Acknowledgements

None.

Conflict of Interest

No conflict of interest.

References

- P Irwin (2004) Technotes 10: Damping Systems Wind-Induced Cable Oscillations, Rowan Williams Davies & Irwin (RWDI).

- G Biju, T Sundararajan, S Geetha (2020) Structural Analyses for a Typical Small Satellite, Advances in Small Satellite Technologies: Proceedings of National Conference on Small Satellite Technology and Applications, pp 155-161.

- R Cao, S El-Tawil, A Agrawal (2020) Miami pedestrian bridge collapse: Computational forensic analysis, Journal of Bridge Engineering 25(1).

- R Fierro, FL Lewis (1997) Control of a nonholonomic mobile robot: backstepping kinematics into dynamics, Journal of Robotic Systems 14(3): 149-163.

- M Tarokh, GJ McDermott (2005) Kinematics modeling and analyses of articulated rovers, IEEE Transactions on Robotics 24(4): 539-553.

- D Huczala, T Kot, M Pfurner, D Heczko, P Oščádal, et al. (2021) Initial estimation of kinematic structure of a robotic manipulator as an input for its synthesis, Applied Sciences 11(8).

- H Goldstein, C Poole, J Safko (2001) Classical Mechanics, Pearson.

- T Wasfy, A Noor (2003) Computational strategies for flexible multibody systems. Appl. Mech. Rev. 56(6): 553-613.

- A Shabana (2020) Dynamics of multibody systems, Cambridge university press.

- R Staszak, M Molska, K Młodzikowski, J Ataman, D Belter (2020) Kinematic structures estimation on the RGB-D images, 25th IEEE International Conference on Emerging Technologies and Factory Automation (ETFA), pp 675-681.

- W Kehl, F Manhardt, F Tombari, SNN Ilic (2017) Ssd-6d: Making rgb-based 3d detection and 6d pose estimation great again, Proceedings of the IEEE international conference on computer vision, pp 1521-1529.

- A Kirillov, E Mintun, N Ravi, H Mao, C Rolland, et al. (2023) Segment anything, IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision, pp 4015-4026.

- JN Juang (1994) Applied System Identification, Englewood Cliffs, NJ: PTR Prentice Hall.

- P Widas, (2008) Introduction to Finite Element Analysis, Virginia Tech Material Science and Engineering.

- T Belytschko, Y Krongauz, D Organ, M Fleming, P Krysl (1996) Meshless methods: an overview and recent developments, Computer methods in applied mechanics and engineering 139(1-4): 3-47.

- L Ljung (2010) Perspectives on system identification, Annual Reviews in Control 34: 1-12.

- R Pintelon, J Schoukens (2001) System Identification A Frequency Domain Approach, New York, NY: IEEE Press.

- EA Medina (1991) Multi-Input, Multi-Output System Identification from Frequency Response Samples with Applications to the Modeling of Large Space Structures, Athens, OH.

- I Markovsky, JC Willems, S van Huffel, B de Moor, R. Pintelon (2005) Application of structured total least squares for system identification and model reduction, IEEE Transaction on Automatic Control 50(10): 1490-1500.

- YC Pati, R Rezaiifar, PS Krishnaprasad, WP Dayawansa (1993) A fast recursive algorithm for system identification and model reduction using rational wavelets, Annual Asilomar Conference on Signals, Systems and Computers pp 35-39.

- B Wahlberg (1986) On model reduction in system identification, Proceedings of the American Control Conference, pp 1260-1266.

- MA Gallivan, RM Murray (2003) Model reduction and system identification for master equation control systems, Proceedings of the American Control Conference, pp 3561-3566.

- WJ Manning, AR Plummer, MC Levesley (2000) Vibration control of a flexible beam with integrated actuators and sensors, Smart Mater. Struct 9: 932-939.

- T Bihl, J Mitchell, R Irwin (2013) Hybrid system identification for MIMO control-system design, IFAC Proceedings Volumes 46(19): 411-416.

- JN Juang, RS Pappa (1985) An eigensystem realization algorithm for modal parameter identification and model reduction, Journal of guidance, control, and dynamics 8(5): 620-627.

- J Noël, G Kerschen (2017) Nonlinear system identification in structural dynamics: 10 more years of progress, Mechanical Systems and Signal Processing 83: 2-35.

- S Chen, SA Billings, PM Grant (1990) Non-linear system identification using neural networks, international journal of control 51(6):1191-1214.

- O Ogunmolu, X Gu, S Jiang, N Gans (2016) Nonlinear systems identification using deep dynamic neural networks.

- M Martínez-Ramón, J Rojo-Alvarez, G Camps-Valls, J Muñoz-Marí, E Soria-Olivas et al. (2006) Support vector machines for nonlinear kernel ARMA system identification, IEEE Transactions on Neural Networks 17(6): 1617-1622.

- T DeWolf, T Stewart, JEC Slotine (2016) A spiking neural model of adaptive arm control.," Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 283(1843).

-

Trevor Bihl* and Timothy Sands. Dynamic System Modeling for Flexible Structures. On Journ of Robotics & Autom. 3(2): 2024. OJRAT.MS.ID.000559.

Robotics, Kinematics, Skyscrapers, Catastrophic, Taxonomy, Dynamics, Finite Element, Hybrid, Single-Output Systems, Eigensystem Realization Algorithm (ERA), Artificial Lung

-

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.

- Abstract

- Introduction

- Precision, Efficiency, and Collaborative Robotics (Cobotics)

- Energy Conservation and Green New Work

- Flexibilization of the workplace and ecological benefits

- Waste reduction, circular economy, and cobotic synergy

- Reduction of Harmful Emissions

- Challenges and Considerations

- Conclusion

- Acknowledgement

- Conflict of Interest

- References