Research Article

Research Article

Data-Driven Hysteresis Modeling and Optimized PID Control for A Piezoelectric Bending Microactuator

Mishek Musa* and Uche Wejinya

Department of Mechanical Engineering, University of Arkansas, Fayetteville, AR 72703

Mishek Musa, Department of Mechanical Engineering, University of Arkansas, Fayetteville, AR 72703.

Received Date:JuLY 11, 2024; Published Date:November 20, 2024

Abstract

In this work, a sparse regression data-driven approach is utilized to characterize the hysteresis in a polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) based piezoelectric bending microactuator. An optimized proportional-integral-derivative (PID) control system based on the beetle antennae search (BAS) algorithm is proposed to be used to control the displacement of the microactuator. The microactuator is made of a two-layer composite beam with a layer of PVDF providing the actuation while the second layer acts as a passive substrate or structural layer that does not actively deform. The system is controlled by a PID controller with optimized gains in simulation to minimize the mean squared error between the desired displacement and the measured displacement by a visual monitoring system. The theoretical model of the system, the working principle of the control algorithm, as well as simulation and experimental validation results are presented. The data-driven hysteresis modeling approach accurately captured the nonlinear dynamics of the system and provide a clear, interpretable representation of the hysteresis phenomenon. The BAS optimized PID controller outperforms the standard Ziegler-Nichols PID auto- tuning method in both the simulated model and experimental implementation of the microactuator and control system.

Introduction

Micromanipulation involves the precise manipulation and control of objects at the micrometer or nanometer scale. The importance of micromanipulation lies in its ability to enable unprecedented levels of control, precision, and analysis, which are essential for advancing scientific research and technological development. Micromanipulation techniques have found applications in various interdisciplinary areas, including but not limited to microfluidics, biomedical engineering, and robotics. They enable the manipulation and analysis of very small volumes of fluids, the fabrication of microscale devices, and the construction of miniaturized robots capable of performing intricate tasks [1]. A crucial component of any micromanipulation system is the microactuator used to create displacements or impart forces on objects.

There are several types of microactuators, each utilizing different principles and mechanisms to generate motion. Some commonly used microactuator technologies include electrostatic actuators [2], piezoelectric actuators [3], shape memory alloy actuators [4], electromagnetic actuators [5], and fluidic actuators [6]. Piezoelectric materials exhibit the ability to generate mechanical strain when subjected to an electric field or, conversely, generate an electric field when subjected to mechanical stress. Compared to the other modes of actuation, piezoelectric microactuators have several advantages including high precision, fast response, and nanometer-scale motion capabilities. Typical piezoelectric actuators are constructed using piezoelectric ceramics or single crystals such as lead zirconate titanate (PZT), quartz, or barium titanate (BaTiO3). One area of research that has gained popularity is the design and control of soft or flexible materials. Unlike the stiff piezoelectric ceramics or crystals, polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) is a piezoelectric polymer that offers flexibility and conformity. Additionally, PVDF exhibits excellent chemical resistance, good electrical insulation, and can be processed or fabricated into different forms relatively easily.

PVDF has been used in a number of microactuation applications, however one particular area of interest is in bending actuators. These bending actuators consist of one or more layers of PVDF along with a passive substrate layer such as a metal or polymer. When an electric voltage is applied, the piezoelectric layer undergoes expansion or contraction, resulting in deflection or displacement of the actuator. The passive substrate provides mechanical support and amplifies the deflection produced by the piezoelectric layer. Due to the piezoelectric and converse piezoelectric properties of PVDF, it can be used as either the actuating component or as a sensing layer in these bending actuators. Shen et al. presented a PVDF based actuator sensor pair for microforce sensing [7, 8]. An optimal servo controller is implemented to impart a balancing force to counteract an externally applied load. Chen et al. designed an integrated ionic polymer-metal composite (IMPC) actuator with PVDF sensing layers to enable feedback control of the actuator system [9]. PVDF has a lower piezoelectric coefficient than other common piezoelectric materials, hence, Kalel et al. designed a PVDF unimoph actuator integrated with a layer of shape memory polymer to enhance the bending performance [10]. A challenge that persists in the realm of piezoelectric actuators, however, is the nonlinear effects of phenomena such as hysteresis. The identification of the system model parameters and its control has garnered increased attention. Traditional methods for modeling the hysteresis effects on piezoelectric actuators include experimental models based on established theories. Some of these models include the Preisach model [11], the Duhem model [12], the Bouc-Wen model [13], and the Prandtl- Ishlinskii model [14]. These models have been shown to effectively capture the nonlinear effects of hysteresis, however, they are not without fault. The Preisach model for example, can be computationally expensive since it requires the determination of a large number of parameters to accurately describe the distribution of relay hysterons. Similarly, the Prandtl-Ishlinskii model can also become quite complex, dependent on the number of elementary operators used to capture the nonlinear and asymmetric hysteresis behavior. Common to most of these approaches is the difficulty in physical interpretation of the models, particularly for those with a large number of parameters.

Recently, data-driven modeling and system identification approaches have been shown to be an effective method of describing hysteresis. One data-driven approach to modeling hysteresis is the use of Deep Neural Networks (DNN) [15]. Wang et al. used a time delay recurrent neural network to design an adaptive control system for a piezo-actuated stage device [16]. Zhao et al. employed a global linearization neural network model to capture the hysteresis behavior of a piezoelectric actuator [17]. While these DNN approaches exhibit impressive performance for prediction of the hysteresis, it can be difficult to interpret the physical meaning of the model due to the black box nature of DNNs and their absence of governing equations. An approach that can mitigate this issue was proposed by Brunton et al. known as Sparse Identification of Nonlinear Dynamics (SINDy) [18]. This datadriven approach can be used to uncover the underlying dynamics of complex systems from observed data. It employs sparse regression techniques to identify the governing equations of the system, revealing the most important terms and interactions. By leveraging sparsity and optimization algorithms, SINDy can efficiently extract concise mathematical models even from noisy or incomplete data, making it a powerful tool for system identification and prediction in various scientific and engineering domains. Some of these domains include medicine [19], robotics [20], and chemical processes [21]. The SINDy approach would be studied further to demonstrate its applicability to nonlinear hysteresis modeling of piezoelectric actuators.

With a comprehensive model describing the input-output relationship of the piezoelectric actuator, control systems can be designed to accurately control the actuator displacement. One common closed-loop controller that is utilized in these microactuators is the proportional-integral-derivative (PID) controller. This type of controller offers several advantages including its simplicity in implementation, versatility across a variety of control problems/applications, and good stability properties. A key pitfall of the PID controller, however, is the complexity and timeconsuming nature of tuning the control gains. Many researchers have investigated conventional tuning methods such as manual tuning or those that necessitate reduced-order models that may not yield satisfactory results. Consequently, in recent years, researchers have increasingly turned to heuristic algorithm-based controller tuning. Typical heuristic algorithms used for controller tuning include genetic algorithms (GA) [22], particle swarm optimization (PSO) [23], and bacterial foraging organization (BFO) [24]. More recently, a biomimetic metaheuristic optimization algorithm called beetle antennae search (BAS) has emerged as a simplistic and efficient alternative to traditional heuristic algorithms [25]. The algorithm derived from the foraging behaviors of beetles has been applied in a number of fields including medicine [26], robotics [27], controls [28], and finance [29].

In this work, the model for a composite PVDF based bending microactuator is developed. The SINDy approach is used to characterize the nonlinear hysteresis effects on the actuator. A simulation-based study is performed to validate the SINDy approach for hysteresis modeling in piezoelectric devices. Experimental data collected is then used to learn a SINDy model to describe the nonlinear hysteresis effects. Using the developed model of the system, a BAS optimized PID controller is developed to enable accurate tip deflection control. The microactuator consists of a PVDF layer mounted to a passive polyimide substrate, where the PVDF layer performs the actuation. The structure is similar to the device presented in our previous works [1, 7, 8], however, rather than utilizing it as a force sensor, this work focuses on a standalone actuation device with deflection or displacement control. Simulation results of the control performance are presented and bench-marked against the classical Ziegler- Nichols PID auto-tuning method. Experiments are then con- ducted to validate the performance. This work builds upon our previous study presented in [30]. The manuscript is organized as follows: Section II introduces the design and theoretical modeling of the microactuator and the hysteresis modeling, Section III presents the BAS optimized PID algorithm, Section IV presents the experiments and simulation results, and conclusions are given in Section V.

System Design and Modeling

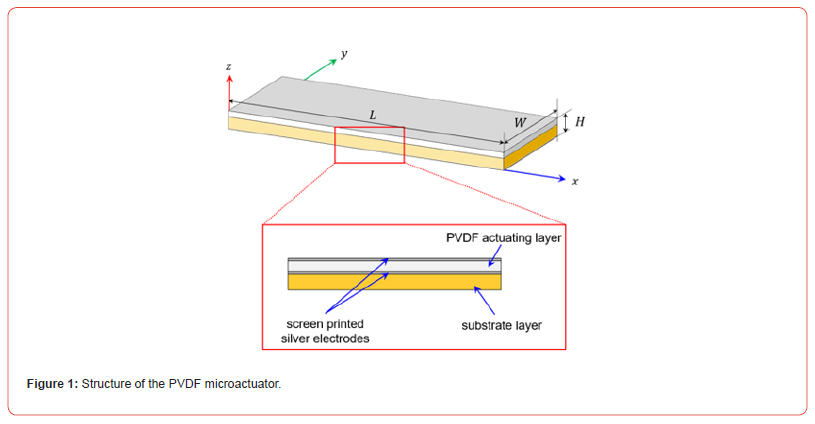

The overall structure of the PVDF microactuator is shown in Figure 1. The microactuator is mounted in a cantilever configuration and is made up of two layers. First is the piezoelectric actuating PVDF layer, and second is a passive polyimide substrate layer. The PVDF layer is coated on both sides with a thin layer of screen-printed silver electrodes. The mechanical effects of the thin electrodes and the glue holding the device together are omitted from the modeling for simplification. The microactuator has a length L, width W, and thickness H = ha + hm where ha and hm are the thicknesses of the actuating and substrate layers, respectively.

Piezoelectric Actuation Model

The first layer of the microactuator is the PVDF actuating layer which is used to generate deflections when subjected to a voltage. An applied voltage, Va (x, t), to the actuating layer induces a stress, σa, along the longitudinal axis given as:

where Ea is the Young’s modulus of the actuating layer, d31 is the transverse piezoelectric coefficient, and ha is the thickness of the layer. Due to the cantilever nature of the composite actuator, the stress induced in the actuator layer generates a bending moment, Ma, along the neutral axis given by [31]:

where the geometry dependent constant, Ca, is given as follows

The relationship between the deflection of any point along the beam wa(x, t) and the actuating voltage Va(x, t) can be described by the Bernoulli-Euler equation with an additional term to account for the actuating voltage given by:

where E is the Young’s modulus of the composite beam, I is the moment of inertia of the composite beam, and ρ is the density. For the composite beam, the flexural rigidity, EI, can be found by EI = EaIa + EmIm and the mass per unit length, ρA, is given by ρA = ρaW ha + ρmW hm. The actuating equation (4) is then subjected to the following boundary conditions:

Utilizing a modal expansion approach [32], the deflection of the beam wa(x, t) can be represented by an infinite series of eigenfunctions given as follows:

where ϕi(x) and qai(t) are the eigenfunctions and the modal displacements corresponding to the ith mode, respectively. The solution for the eigenfunctions ϕi(x) for the natural modes of the beam is then given by:

where λi are the dimensionless frequency values solved for by the following characteristic equation of a cantilever beam:

In the case of the first vibration mode, λ1 = 1.875. The undamped natural frequency of the system can be solved for by the following equation:

By using Lagrange’s equation of motion and orthogonality conditions and principles, the differential equation corresponding to each mode shape is then given by:

where a dot represents a derivative with respect to time, while a prime indicates a derivative with respect to position. This equation gives the relation between actuating voltage and tip displacement. Then, taking the Laplace transformation of 13, the dynamic relationship between the modal displacements qai(s) and the input voltage Va(s) is given as

This transfer function describes the modal displacements of the flexible beam due to a voltage applied to the actuating PVDF layer.

Hysteresis Modeling with SINDy

It is known that a nonlinear hysteresis relationship exists between the input voltage Va(t) and the charge Q(t) produced between the electrodes for piezoelectric materials [33]. This thereby affects the displacement wa(t) of the actuator. To characterize the hysteresis effect on the piezoelectric actuator, a data-driven approach is implemented on experimental data. In this work, the SINDy approach proposed by Brunton et al. is employed [18]. SINDy is a powerful data-driven technique used in dynamical systems to uncover the governing equations that describe the system’s behavior, even when the available data is limited or noisy. It leverages sparsity-promoting techniques to identify the significant terms in the equations from sparse measurements.

The nonlinear hysteresis effect of the piezoelectric actuator can be modeled as follows:

where x ∈ n is the state of the system, u ∈ n is the input to the system, and f(x, u) is a function defining the nonlinear dynamic system. Time-series data of the input u and the output x can be collected along with their derivatives, which can be directly measured or computed numerically. The data can then be organized into two matrices X and U as follows

where 1≤ i ≤ n, and a dot represents a derivative with respect to time. A library Θ(X, U) of candidate nonlinear functions can then be constructed consisting of the columns of the matrices X and U. The library is typically made up of constants, polynomials, and trigonometric functions as follows:

where ⊗ denotes the vector of product combinations of components in the given matrices. The objective is them to obtain a set of sparse coefficient vectors Ξ = [ξ1 ξ2…ξn] that determines which combinations of candidate functions in Θ are active. This sparse regression approach to approximating the system dynamics can be used to rewrite (15) as

The approach is considered sparse since the equations governing the system’s behavior can often be described using only a small number of terms or features from a larger set of possible candidates. In this work, the library of candidate functions are made up of terms from the Bouc-Wen hysteresis model [13] and higher order polynomials and their combinations. The Bouc-Wen hysteresis model is defined as follows:

where w(t) is the deflection of the piezoelectric actuator, u(t) is the control voltage input, and α, β, γ, and n are dimensionless quantities that control the behavior of the model. A simulationbased experiment is conducted to validate the approach, followed by the characterization train on data collected experimentally with the fabricated piezoelectric actuator. The learned hysteresis model is then combined with the actuator model from Section IIA to create the comprehensive model of the piezoelectric actuator.

Closed-Loop Position Control

PID Control

In order to accurately control the position of the tip of the PVDF microactuator, a closed-loop controller must be implemented. In this case, the sensing layer of the microactuator feeds back the position of the tip in real time and can be used to minimize the error e(t) = r(t) y(t) between the desired position r(t) and the current position y(t). One conventional control approach is the proportional-integral- derivative (PID) controller. The general working principle of the PID controller is that the error of the system is input to the controller where it is then acted upon by the proportional, integral, and derivative components of the controller to generate a new control signal. As time progresses, the error is reduced and so the current position of the microactuator tends towards the desired position. The control signal u from the PID controller is given as follows:

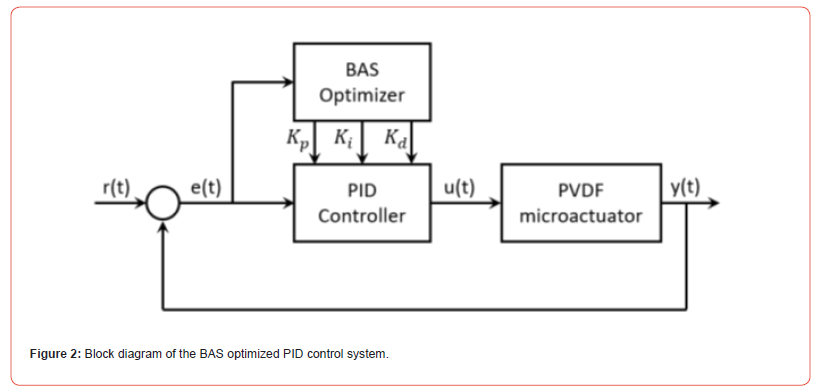

where Kp, Ki, and Kd are the proportional, integral, and derivative gains respectively. The values of these gains are critical to the performance of the controller. Often it can be difficult and cumbersome to manually tune the PID gains, and so in this work the BAS algorithm is used to automatically optimize the control parameters.

Beetle Antennae Search (BAS)

In order to fine-tune the gains of the PID controller, a biomimetic metaheuristic algorithm called beetle antennae search is employed [25]. The BAS algorithm is based on the behavior exhibited by beetles whereby they use their antennae to locate and explore their environment in search of various stimuli, particularly in search of food. Beetles have two antennae they use to explore their environment and if the smell of food is stronger on the left side antennae than the right side, the beetle will move in that direction, and vice versa.

In this case, the strength of the food odor/scent for a beetle position xt can be denoted as the value at the point of the objective function f(x). The beetle’s search behavior can be modeled by defining a random search direction b given as:

where randn() indicates a random function, and k represents the dimension of the search space. The searching behaviors of both the antennae in terms of their position’s xl for the left and xr for the right are formulated as follows:

where dt is the sensing length of the antennae which corresponds to the ability to exploit at a given time step. The subsequent position of the beetle can then be updated based on the direction of the detected odor. The updated position is given as follows:

where δt is a step size that accounts for the pace of convergence, and sign() indicates a sign function. The search parameters dt and δt can then be updated by:

The BAS algorithm is summarized in Algorithm 1.

Beetle Antennae Search Optimized PID

In order to tune the PID controller using the BAS algorithm, we can define the search dimension k to be 3, corresponding to the three control gains of the PID con- troller. Secondly, the BAS algorithm requires an objective function to minimize; in this case, the mean square error (MSE) between the desired position and the current position measured by the sensing layer is used. For n samples, the MSE is defined as follows:

A block diagram of the BAS optimized PID controller is presented in figure 2. The beetle positions are decomposed into its three dimensions and input to the PID controller as the three control gains. The control system is ran and the performance of the gains are evaluated according to the MSE. In the given search space, the beetle then updates the position of the antennae and subsequently the overall position of the beetle until the maximum iterations are reached. A flow chart of this process is presented in Figure 3. As shown in the flowchart, the primary functionality of the BAS algorithm is implemented in Matlab, and the

PVDF microactuator control system is simulated in Simulink according to the equations described in Section II.

Experiments & Results

Simulation Validation of SINDy for Hysteresis Modeling

The SINDy approach for hysteresis modeling is first validated using a simulation experiment. The data for the experiment is generated using the Bouc-Wen hysteresis model given in (23) with α = 10, β = 0.75, γ = 0.5, and n = 1. A python implementation of SINDy known as PySindy [34] was used for the model generation and for computing the time derivatives of the input and output data. The error is computed using the relative percentage error as follows

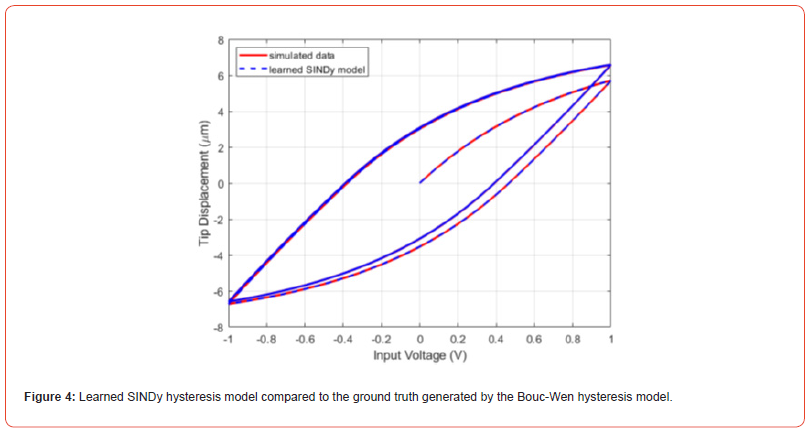

where wˆ is the solution from the SINDy model, and ∥w∥2 refers to the L2-norm of the argument. In the simulated experiment, the input voltage to the system is a sinusoidal signal given as u(t) = sin(t). Figure 4 shows the results of this experiment comparing the learned SINDy hysteresis model with the ground truth generated by the Bouc-Wen hysteresis model. It can be seen that there is good agreement between learned model and the ground truth. The relative error was found to be 2.74 10−6%. This indicates that the SINDY approach can be applicable to hysteresis modeling.

Experimental SINDy Hysteresis Modeling

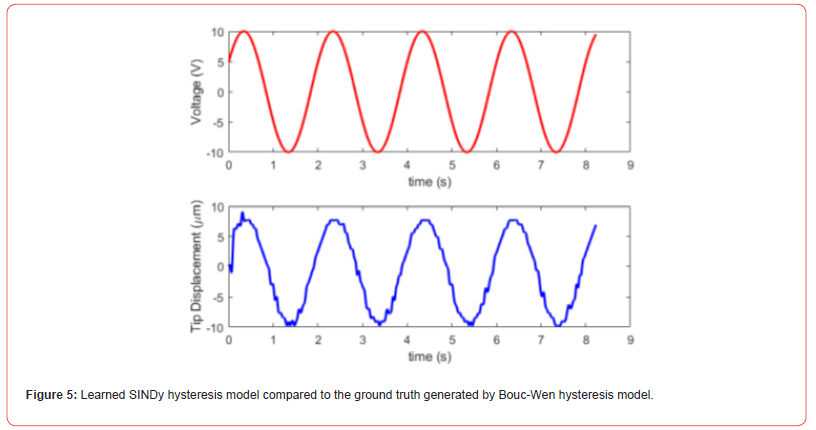

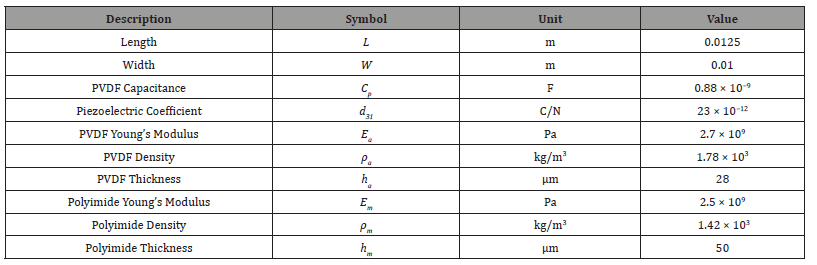

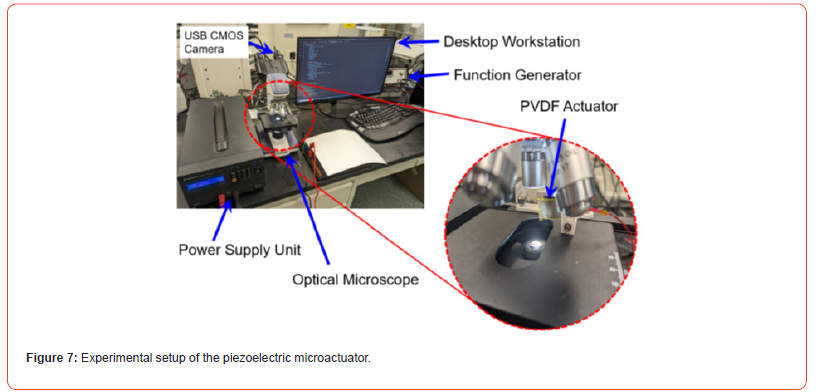

The SINDy approach to hysteresis model is then used to characterize the effect of hysteresis on the real piezoelectric actuator. The microactuator was fabricated according to the dimensions and parameters specified in Table I. The PVDF layer (PolyK Technologies, USA) was bonded to a polyimide substrate layer (ELEGOO, China) using a thin layer of cyanoacrylate adhesive. Thin lead wires were connected to both sides of the actuating layer using conductive copper tape and solder. The microactuator was mounted to a 3D printed bracket affixed to a calibrated 4 microscope (AmScope, USA). The lead wires were connected to a function generator (Agilent Technologies, USA) to provide a sinusoidal voltage to the actuating layer given by u(t) = 10 sin (πt + 0.5). A short 15 μm diameter wire was fixed to the end of micro actuator to allow for better visualization under the microscope. A USB CMOS camera (MD130, AmScope, USA) connected to the eyepiece of the microscope was connected to an external computer and the python package OpenCV [35] was used for image processing to acquire the tip deflection of the actuator. The image processing workflow involved image capturing → grayscale conversion & Gaussian filtering →contour detection→tip identification→ pixel toμm conversion . Images were captured at 30 fps and used to measure the tip deflection as the sinusoidal voltage was applied. The measured tip displacement can be seen in Fig. 5. It can be seen that the data is a bit noisy and limited, but the SINDy approach can still uncover the dominant, leading- order effects [36].

Table 1: Parameters used for the fabrication & simulation of the PVDF microactuator.

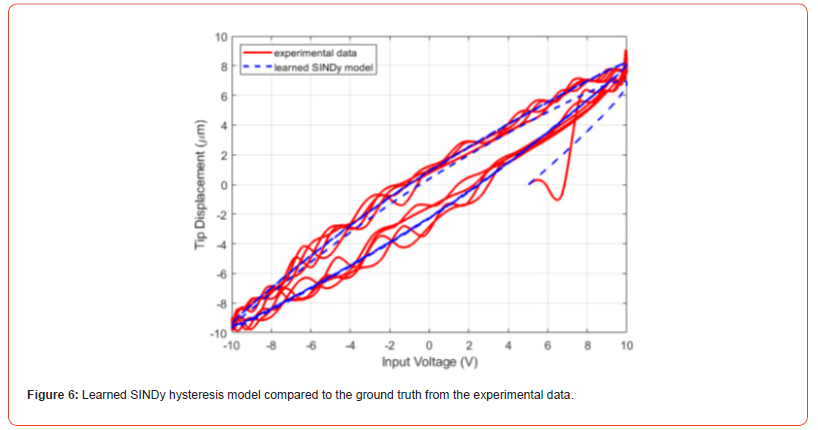

Figure 6 shows the results of this experiment comparing the learned SINDy hysteresis model with the experimental hysteresis loop. Similar to the simulation experiment, there is good agreement between learned model and the ground truth. The relative error was found to be 0.95%. The learned hysteresis model was identified as

The physical interpretation of this equation lies in understanding that an increase in either the input voltage or its rate of change leads to a corresponding rise in the rate of change of the output displacement. Conversely, an increase in the displacement or its absolute value results in a decrease in the rate of change of the displacement.

Simulation Setup

The PVDF microactuator, with both the actuation model and the learned SINDy nonlinear model, was simulated in Simulink using the equations described in Section II-A and the equation found in Section IV-B. The parameters used for the microactuator simulation can be seen in Table I. The PID control system was also simulated in Simulink according to (21). A Matlab script was written implementing the BAS algorithm that was capable of receiving outputs from the Simulink simulation as well as updating parameters, namely the PID control gains.

Model Verification

The actuating performance of the PVDF microactuator system was verified experimentally using the setup seen in Figure 7. A programmable power supply unit (BKPrecision, USA) was interfaced with an external computer and con- trolled with a python script using the PyVISA package. SCPI (Standard Commands for Programmable Instruments) commands were sent to the power supply unit to increase the voltage from 0 V to 50 V in 1 V increments and then decreasing the voltage back down to 0 V. The displacement of the tip of microactuator was again recorded using the calibrated microscope system and the image processing workflow. The results of this experiment can be seen in Figure 8 where the black line is the theoretical displacement-voltage curve, the red asterisks markers indicate the recorded experimental displacements in the step-up calibration, and the blue circle markers indicate the recorded experimental displacements in the step-down calibration. The red and blue dashed lines indicate a least squares regression best fit line for the step- up and step-down calibration data respectively. The fit for the step-up calibration data was found to have an R2 value of 0.99, and the fit for the step-down calibration data was found to have an R2 value of 0.98. From the experimental verification, it can be seen that the microactuator has a sensitivity of 0.473 μm/V.

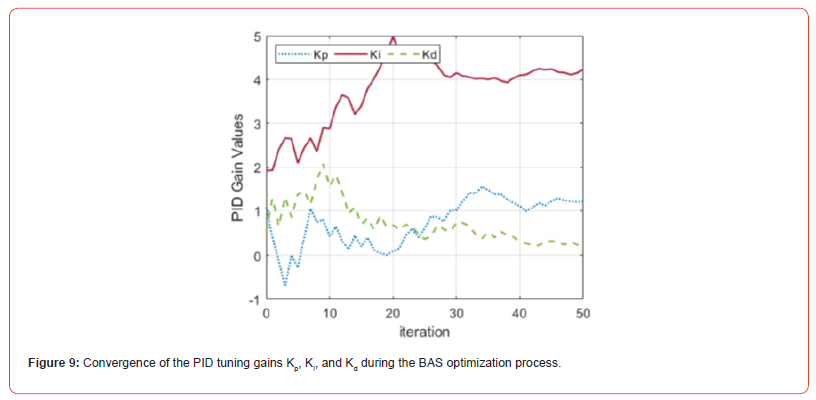

Simulation Analysis of the BAS optimized PID Controller

In this section, the performance of the BAS optimized PID controller, denoted by BAS-PID, is compared to the traditional Ziegler-Nichols PID tuning method, denoted by ZN-PID. The simulation time was set to 2 s with a time- step of 0.01 s. The maximum number of iterations for the BAS algorithm was set to Tmax = 50. The reference tip displacement for the microactuator was 10 μm. Figure 9 shows the convergence of the tuning gains during the BAS optimization process. It can be seen that each of the tuning gains are able to converge to their final value relatively quickly, within 30 iterations.

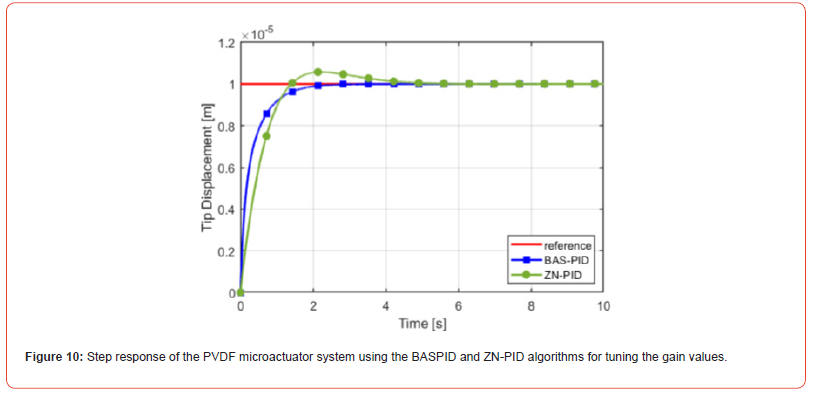

The step response of the system from both tuning methods is shown in Figure 10. Here it can be seen that the BAS-PID algorithm converges to steady state with no overshoot with a rise time of 0.88 s and a settling time of 1.74 s. The ZN-PID on the other hand has significant overshoot of 5.7% and a rise time of 0.96 s and a settling time of 3.82 s.

Experimental Analysis of the BAS optimized PID Controller

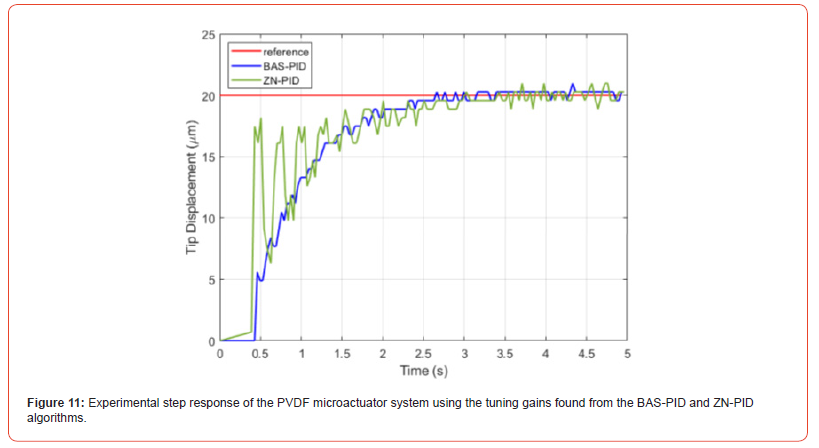

The micro actuator was again set up according to the experimental setup described above. A PID control algorithm was implemented in python according to (21) and used to generate command voltages to send to the microactuator based on the tip deflection measured by the vision system. The output from the power supply was limited to 50 V for these experiments, however, it is possible to increase the operating range. A setpoint of 20 μm was given to the control system. The tuning gains of the PID controller were set in accordance with the values found from the offline BASPID optimization, and the ZN tuning method. The performance of the controllers can be seen in Figure 11. From this we can see that the step-response with the gains tuned by the BAS-PID algorithm closely agrees with the simulation result as there is a relatively fast response with little to no overshoot. The behavior of the ZN tuned PID controller on the other hand has large initial oscillations that can likely be associated with the derivative gain of the controller being too high. Again, the BAS-PID algorithm outperforms the traditional ZN tuning method.

Conclusion

In this study, a comprehensive theoretical framework for a composite layered PVDF-based microactuator was introduced and studied, serving as the basis for the development of a PID control system optimized through the application of the biomimetic metaheuristic BAS algorithm. The developed model encapsulates both the intricate dynamics of actuation and the nonlinear nuances of hysteresis effects. Leveraging the powerful sparse regression technique, SINDy, the nonlinear hysteresis phenomena was characterized, initially validating against the established Bouc- Wen model and subsequently extracting nonlinear dynamics from experimental data. Through meticulous experimentation with the fabricated microactuator under a microscope with visual displacement feedback, good agreements were observed between the developed model and empirical data. Employing simulation studies, the performance of the BAS-PID controller was evaluated against the conventional ZN-PID method, revealing superior outcomes with the former, including minimized overshot and accelerated transient response to steady state. Transitioning from simulation to practical implementation, the offline-tuned control gains effectively governed the real microactuator, corroborating the efficacy of the BAS-PID approach. This preliminary exploration not only underscores the viability of SINDy as a potent tool for nonlinear hysteresis characteristics in piezoelectric actuators, but also highlights the potential of BAS in optimizing control systems for micro- and nano-scale applications.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Evans Addo-Mensah, Nahid Tushar, and Charith Nanayakkara Ratnayake for providing access to key equipment used for experiments.

This work was partially supported by Twenty First Century Endowed Professorship in Mechanical Engineering at the University of Arkansas.

Conflict of Interest

No conflict of interest.

References

- UC Wejinya, Y Shen, N Xi, F Salem (2006) Force measurement of embryonic system using in situ PVDF piezoelectric sensor, in 2006 49th IEEE International Midwest Symposium on Circuits and Systems 1: 108-112.

- J Grade, H Jerman, T Kenny (2003) Design of large deflection electrostatic actuators, Journal of Microelectromechanical Systems 12(3): 335-343.

- J Li, Y Liu, J Deng, S Zhang, W Chen (2022) Development of a linear piezoelectric microactuator inspired by the hollowing art, IEEE Transactions on Industrial Electronics 69(10) 10407-10416.

- H Sun, J Luo, Z Ren, M Lu, D Nykypanchuk, et al. (2020) Shape Memory Alloy Bimorph Microactuators by Lift- Off Process, Journal of Micro and Nano-Manufacturing 8: 031003.

- M Dehghan, M Tahmasebipour, S Ebrahimi (2022) Design, fabrication, and characterization of an sla 3d printed nanocomposite electromagnetic microactuator, Microelectronic Engineering 254: 111695.

- B Gorissen, W Vincentie, F Al-Bender, D Reynaerts, MD Volder (2013) Modeling and bonding-free fabrication of flexible fluidic microactuators with a bending motion, Journal of Micromechanics and Microengineering 23: 045012.

- Y Shen, N Xi, C Pomeroy, U Wejinya, W Li (2005) An active micro-force sensing system with piezoelectric servomechanism, in 2005 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems, pp 2381-2386.

- Y Shen, E Winder, N Xi, C Pomeroy, U Wejinya (2006) Closed-loop optimal control-enabled piezoelectric microforce sensors, IEEE/ASME Transactions on Mechatronics 11(4): 420-427.

- Z Chen, KY Kwon, X Tan (2008) Integrated IPMC/PVDF sensory actuator and its validation in feedback control, Sensors and Actuators A: Physical 144(2): 231-241.

- S Kalel, WC Wang (2021) Integration of SMP with PVDF unimorph for bending enhancement, Polymers 13(3).

- S Xiao, Y Li (2012) Modeling and high dynamic compensating the rate-dependent hysteresis of piezoelectric actuators via a novel modified inverse preisach model, IEEE Transactions on Control Systems Technology 21(5) 1549-1557.

- H Ji, B Lv, H Ding, F Yang, A Qi, et al. (2022) Modeling and control of hysteresis characteristics of piezoelectric micro-positioning platform based on duhem model, in Actuators 11: 122.

- YK Wen (1976) Method for random vibration of hysteretic systems, Journal of the engineering mechanics division 102(2): 249-263.

- H Jiang, H Ji, J Qiu, Y Chen (2010) A modified Prandtl-ishlinskii model for modeling asymmetric hysteresis of piezoelectric actuators, IEEE Transactions on Ultrasonics, Ferroelectrics, and Frequency Control 57(5): 1200-1210.

- T Kim, OS Kwon, J Song (2019) Response prediction of nonlinear hysteretic systems by deep neural networks, Neural Networks 111: 1-10.

- Y Wang, M Zhou, C Shen, W Cao, X. Huang (2023) Time delay recursive neural network-based direct adaptive control for a piezo- actuated stage, Science China Technological Sciences 66(5): 1397-1407.

- B Zhao, X Qi, W Shi, J Tan (2023) Global linearization identification and compensation of no resonant dispersed hysteresis for piezoelectric actuator, IEEE/ASME Transactions on Mechatronics.

- SL Brunton, JL Proctor, JN Kutz (2016) Discovering governing equations from data by sparse identification of nonlinear dynamical systems, Proceedings of the national academy of sciences 113(15): 3932-3937.

- YX Jiang, X Xiong, S Zhang, JX Wang, JC Li, et al. (2021) Modeling and prediction of the transmission dynamics of covid-19 based on the sindy-lm method,” Nonlinear Dynamics 105(3): 2775-2794.

- J Chen, M Zhang, Z Yang, L Xia (2021) A robust data-driven approach for dynamics model identification in trajectory planning, in 2021 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems (IROS), 7104-7111.

- B Bhadriraju, A Narasingam, JSI Kwon (2019) Machine learning- based adaptive model identification of systems: Application to a chemical process, Chemical Engineering Research and Design 152: 372-383.

- EW Suseno, A Maarif (2021) Tuning of pid controller parameters with genetic algorithm method on dc motor, International Journal of Robotics and Control Systems 1(1): 41-53.

- H Feng, W Ma, C Yin, D Cao (2021) Trajectory control of electro-hydraulic position servo system using improved pso-pid controller, Automation in Construction 127: 103722.

- A Manjula, L Kalaivani, M Gengaraj, R Maheswari, S Vimal, et al. (2021) Performance enhancement of SRM using smart bacterial for- aging optimization algorithm-based speed and current pid controllers, Computers and Electrical Engineering 95: 107398.

- X Jiang, S Li (2017) Bas: beetle antennae search algorithm for optimization

- D Chen, X Li, S Li (2023) A novel convolutional neural network model based on beetle antennae search optimization algorithm for computerized tomography diagnosis, IEEE Transactions on Neural Networks and Learning Systems 34(3): 1418-1429.

- Q Wu, H Lin, Y Jin, Z Chen, S Li, et al. (2020) A new fallback beetle antennae search algorithm for path planning of mobile robots with collision-free capability, Soft Computing 24: 2369-2380.

- L Zhou, K Chen, Z Chen, H Dong, D Song (2020) Course control of unmanned sailboat based on BAS-PID algorithm, in 2020 International Conference on System Science and Engineering (ICSSE), 1-5.

- SD Mourtas, VN Katsikis (2022) V-shaped BAS: applications on large portfolios selection problem, Computational Economics 60(4): 1353-1373.

- M Musa, U Wejinya (2023) Optimized pid control for a piezoelectric bending microactuator, in 2023 International Conference on Manipulation, Automation and Robotics at Small Scales (MARSS), 1-6.

- S Moheimani (2000) Experimental verification of the corrected transfer function of a piezoelectric laminate beam, IEEE Transactions on Control Systems Technology 8(4): 660-666.

- L Meirovitch (1986) Elements of vibration analysis, ch. 5. McGraw-Hill.

- J Yi, S Chang, Y Shen (2009) Disturbance-observer-based hysteresis compensation for piezoelectric actuators, IEEE/ASME Transactions on Mechatronics 14(4): 456-464.

- B de Silva, K Champion, M Quade, JC Loiseau, J Kutz, et al. (2020) Pysindy: A python package for the sparse identification of nonlinear dynamical systems from data, Journal of Open-Source Software 5(49): 2104.

- G Bradski (2000) The OpenCV Library, Dobb’s Journal of Software Tools.

- BM de Silva, DM Higdon, SL Brunton, JN Kutz (2020) Discovery of physics from data: Universal laws and discrepancies, Frontiers in artificial intelligence 3: 25.

-

Mishek Musa* and Uche Wejinya. Data-Driven Hysteresis Modeling and Optimized PID Control for A Piezoelectric Bending Microactuator. On Journ of Robotics & Autom. 3(3): 2024. OJRAT.MS.ID.000561.

Polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF); Proportional-Integral-Derivative (PID); Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO); Robotics; SINDy, Sensing Parameters; Beetle Antennae Search (BAS); Actuators; Genetic Algorithms (GA)

-

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.

- Abstract

- Introduction

- Precision, Efficiency, and Collaborative Robotics (Cobotics)

- Energy Conservation and Green New Work

- Flexibilization of the workplace and ecological benefits

- Waste reduction, circular economy, and cobotic synergy

- Reduction of Harmful Emissions

- Challenges and Considerations

- Conclusion

- Acknowledgement

- Conflict of Interest

- References