Case Report

Case Report

Decompensated cirrhosis, successful completion of ninth pregnancy and request for future contraception by a 43-years old lady

Nizamuddin1, Waheed Iqbal1*, Irum Mehmood1 and Samiullah2

1Department of Pharmacology, Khyber Medical College Peshawar, Pakistan

1Bannu Medical College, Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, Pakistan

Waheed Iqbal, Department of Pharmacology, Khyber Medical College Peshawar Pakistan.

Received Date:December 06,2022; Published Date:December 16, 2022

Abstract

Objective: Hepatitis-C Virus (HCV), along with hepatitis-B is responsible for more than 75% of chronic liver disease worldwide. Chronic

hepatitis-C (CHC) remains silent for years and can present for the first time with decompensated cirrhosis. Although pregnancy is rare in patients

with cirrhosis due to liver damage and amenorrhea, but some time cirrhotic patient can get pregnant and can be present in acute decompensated

state. This doubles the risk for cirrhosis related complications like portal hypertension, ascites and hepatic encephalopathy due to hemodynamic

changes, which occur during pregnancy. The life of both mother and fetus are at risk and thus optimal management that basically revolves to focus

on cirrhosis related complication for rescuing both mother and fetus become the goal in such cases. To manage such cases properly, we need a

multi-specialty approach, involving obstetricians experienced in dealing with high-risk cases, hepatologists and neonatologists for a better outcome

of pregnancy. Due to recent advancement in the medical field, pregnancy is not contra-indicated in early cirrhosis, as was previously believed, but

needs a special approach to manage cirrhosis via multi-disciplinary team.

ase: This interesting case, which is described in the following report shows that patients with chronic hepatitis-C may present for the first time

with decompensated cirrhosis in pregnancy. It also demonstrates that such patients can be managed properly to get good outcome of pregnancy

both for mother and baby.

Conclusion: Pregnancy can occur in female with cirrhosis due to chronic hepatitis-C. For better outcome, multi-specialty teams should manage

such patients. Cirrhosistechniques and intervention, cirrhosis related complications can be minimized and vertical transmission of HCV to the fetus

can be prevented.

Keywords:Chronic hepatitis-C; Cirrhosis; Pregnancy; Complication of cirrhosis

Introduction

Chronic hepatitis-C (CHC) is a chronic disease, with a global prevalence of 2.2%, affecting almost 130 million people worldwide [1]. The incidence of new cases in developed countries are now reduces extensively due to screening measure before transfusion of blood, surgery, organs transplantation, improved health and hygiene practices but still the prevalence is high in developing countries due to low literacy level, paucity of health care services and poor health and hygiene practices, in achieving a similar milestone [2]. New cases are accidentally diagnosed during routine screening or when they are presented with advanced complication of cirrhosis. It has got a substantial impact on morbidity, mortality and utilization of health budget [2]. There are several factors that determine the success of HCV antiviral therapy and progression of the disease to complications like cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC). Among those high base-line viral load is the most notable one and really needs aggressive approach [3]. Therefore, aggressive treatment is needed to achieve sustained virological response (SVR), which is the only surrogate outcome in the treatment of chronic hepatitis-C (CHC). In these Patients, SVR shows total clearance of virus and thus decreases risk of cirrhosis and HCC [3]. In last decade, the treatment strategy for chronic hepatitis-C (CHC) is rapidly evolving from conventional interferon plus weightbased ribavirin to Pegylated-Interferon plus weight-based ribavirin as dual therapy (DT) and now to highly effective triple therapy (TT) including pegylated-interferon-alfa, ribavirin and nucleotide analogue NS5B HCV RNA dependent RNA polymerase inhibitor, sofosbuvir. The TT boasts higher efficacy, cost-effectively, shorter treatment duration and a much more agreeable adverse effects profile. However, there is still little clinical data available from other countries, especially the ones with higher hepatitis-C prevalence. A simple example of discordance among different cohorts is recently reported on genotype 2 in Germany [4]. Furthermore, it is important to realize that factor such cirrhosis, age, gender, baseline viral load, viral genotype, certain IL28b SNP genotypes [5,6] seem to greatly reduce the effect of antiviral therapy.

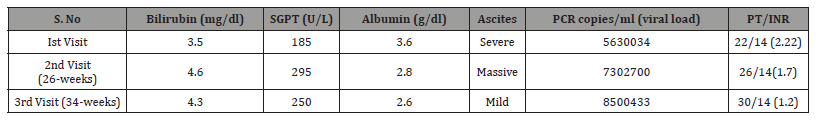

Case

This 43-years old lady, who was G9P8 presented this time in the first trimester of her 9th pregnancy. The estimated gestational duration was 11-weeks. Her basic concern was the rapid enlargement of her abdominal size in last 3-weeks. Basically, she was expecting the rapid enlargement of her baby. She was also complaining of poor appetite, hyperemesis graviderm and exertional dyspnea right from the very first day, when she got pregnant this time. There was no past history of any significant medical illnesses, blood transfusion, hospitalization and surgery. She denied contact with hepatitis patients, medication intake, and alcohol or toxin exposure. On general physical examination, she was pale, malnourished with poor general hygiene, pulse was 80/mint, blood pressure 110/80mmHg, having palmer erythema, plenty of spider angiomatas and pedal edema. On systemic examination, she has clinically significant ascites with no visceromegally. The rest of the systemic examination was normal. Initial laboratory investigation was done, showing some positive finding like (hemoglobin) Hb- 9gm/dl, HCV+v, (bilirubin) Bil=3.5mg/dl, SGPT=185, (prothrombin time) PT>8seconds prolonged, albumin<3.6gm/dl, (random blood sugar) RBS=167mg/dl and ultrasound abdomen and pelvis was showing moderate ascites, shrunken liver, mild splenomegaly and intera uterine gestational sac with an estimated gestational duration of 11-weeks. Her initial viral load was 5630034-copies/ ml and was infected by HCV genotype-3. She was admitted and endoscopy was done, showing early esophageal varices with no risk of bleeding. She was put on the standard treatment of decompensated cirrhosis and prophylaxis was done for sub-acute bacterial peritonitis (SBP). After counseling with obstetrician, she was offered medical termination of pregnancy, but the patients and the attendant refused. She was put on diuretics (furosemide 20mg), low doses beta-blockers (bisoprolol 2.5mg), lactulose and third generation cephalosporin (cefixime 400mg OD) as prophylaxis of SBP and was discharged. She was advised to take an early follow up visit, but unluckily she was lost for follow up. After 26 weeks, the same patients landed again in the ward. This time, she had massive ascites and sub-acute bacterial peritonitis (SBP). She was successfully treated and discharged. She was also counseled for termination of pregnancy, but she promised close follow up, but refused termination. She came once again after 10 weeks, but this time with a better outlook and clinical profile. Due to rapid increase in the viral load, she was put on sofosbuvir and ribavirin and was discharged. He was advised to use these medications for 6-months. This time, she lasts for follow up for good 16-months. After 16-months, she presented in the OPD with a healthy baby and was clinically much improved. But it was really interesting and encouraging, that this time her main request was to advise her of some safe medications or procedure for future contraception. Her viral load was undetectable, and she has a no ascites. She was advised to continue low dose diuretics, low doses beta-blockers, lactulose and was referred to gynecologist for laparoscopic tube ligation (Table 1).

Table 1:All the data/parameters of the patient during her first and follow up visits.

Discussion

It is evident from literature that pregnancy is usually a rare event in patients with cirrhosis and has traditionally been low for two reasons. First, advanced liver disease does not typically occur until well after most patients have completed their reproductive years, with only 45 cases of cirrhosis occurring in every 100,000 women of reproductive age and second, cirrhosis leads to anovulation and amenorrhea due to many factors that include disturbed estrogen and endocrine metabolism [7]. But risk of spontaneous abortion, prematurity and perinatal death rate is usually high in all successful pregnancies in cirrhotic woman, which can kill a number of cirrhotic pregnant ladies [8]. Review of literature has shown that there is 10-15% risk of abortion in early pregnancy and 45 out of 69 babies born to cirrhotic mothers survived the neonatal period [9-11]. It is noted that cirrhotic patients have a high risk of liver decompensation because of worsening synthetic liver function, development of ascites, and hepatic encephalopathy. In such cases maternal mortality rate is as high as 10.5% has been described in this group and their prognosis mainly depends on the degree of hepatic dysfunction during pregnancy rather than its cause [12,13]. It is clinically evident that portal hypertension worsens during pregnancy because there is both an increase in blood volume and flow. Moreover, portal pressures are also high because of an increased vascular resistance due to external compression of the inferior vena cava by the gravid uterus and ascites. Bleeding episodes are noted in up to 27% of patients during the course of pregnancy and usually worst in second and last trimester [12,14]. In all these patients, ‘splenic rupture, hepatic encephalopathy and peripartum bleeding also remains the major concern and causes of death in this setting [12].

In the post-partum period, there is high incidence of gastrointestinal hemorrhage responsible for 5 out of 7 deaths during this period but, severe intra-abdominal hemorrhage of unknown source which may be due to cirrhosis related low platelet count, DIC related coagulopathy or from portal hypertension related intra-abdominal varices which could not be visualized even endoscopically in our settings, may pose different risk [11]. Though clinically, practically and theoretically impossible, with proper management the patient and teamwork have made it possible good recovery. Thus, the patient has made a very good response to therapy, and successful delivery of the baby after nine months became possible. This was become possible after a complete and coordinated teamwork by enthusiastic physician, gynecologist and that of lab technologist.

Conclusion

Pregnancy is difficult to be successfully managed and fruitfully terminated in cirrhotic patients, but teamwork including physician, hepatologist and gynecologist can make it possible with their dedicated approach.

Acknowledgment

None.

Conflict of Interest

No conflict of interest.

References

- Ward JW (2013) The hidden epidemic of hepatitis C virus infection in the United States: occult transmission and burden of disease. Topics in antiviral medicine 21(1): 15-19.

- Vietri J, Prajapati G, El Khoury AC (2013) The burden of hepatitis C in Europe from the patients' perspective: a survey in 5 countries. BMC gastroenterology 13: 16.

- Ge D, Fellay J, Thompson AJ, Simon JS, Shianna KV, et al. (2009) Genetic variation in IL28B predicts hepatitis C treatment-induced viral clearance. Nature 461(7262): 399-401.

- Tacke F, Gunther R, Buggisch P, Klinker H, Schober A, et al. (2016) Treatment of HCV genotype 2 with sofosbuvir and ribavirin results in lower SVR rates in real life than expected from clinical trials. Liver international: official journal of the International Association for the Study of the Liver 37(2): 205-211.

- Esposito I, Trinks J, Soriano V (2016) Hepatitis C virus resistance to the new direct-acting antivirals. Expert opinion on drug metabolism & toxicology 12(10): 1197-1209.

- Aqel BA, Pungpapong S, Leise M, Werner KT, Chervenak AE, et al. (2015) Multicenter experience using simeprevir and sofosbuvir with or without ribavirin to treat hepatitis C genotype 1 in patients with cirrhosis. Hepatology 62(4): 1004-1012.

- Tan J, Surti B, Saab S (2008) Pregnancy and cirrhosis. Liver Transplantation 14(8): 1081-1091.

- Liver IAftSot (2016) AISF position paper on liver disease and pregnancy. Digestive and Liver Disease. 48(2): 120-137.

- Britton RC (1982) Pregnancy and esophageal varices. The American Journal of Surgery 143(4): 421-425.

- Varma RR, Michelsohn NH, Borkowf HI, Lewis JD (1977) Pregnancy in cirrhotic and noncirrhotic portal hypertension. Obstetrics & Gynecology 50(2): 217-222.

- Schreyer P, Caspi E, El-hindi JM, Eshchar J (1982) Cirrhosis-Pregnancy and Delivery: A Review. Obstetrical & gynecological survey 37(5): 304-312.

- Begum M, Begum H (2016) Massive intra-abdominal Haemorrhage in a Pregnant Patient with Cirrhosis of Liver-A Case Report. Bangladesh Journal of Obstetrics & Gynaecology 28(2): 100-102.

- Steven M (1981) Pregnancy and liver disease. Gut 22(7): 592.

- Aggarwal N, Negi N, Aggarwal A, Bodh V, Dhiman RK (2014) Pregnancy with portal hypertension. Journal of clinical and experimental hepatology 4(2): 163-171.

-

Nizamuddin, Waheed Iqbal*, Irum Mehmood and Samiullah. Decompensated cirrhosis, successful completion of ninth pregnancy and request for future contraception by a 43-years old lady. Open J Pathol Toxicol Res. 1(3): 2022. OJPTR.MS.ID.000513.

-

Multi-disciplinary, Blood, Surgery, Organ’s transplantation, Sustained virological response, Dual therapy, Ribavirin, Nucleotide analogue

-

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.