Research Article

Research Article

Validation of Clinical Assessment for Diagnosing Dysphagia in Infants with Chronic Encephalopathy

Brenda Carla Lima Araújo1*, Adriana Guerra De Castro2, Thales Rafael Correia De Melo Lima3, Amanda Louize Félix Mendes4, Carlos Kazuo Taguchi5, Silvia De Magalhães Simões6 and Cláudia Marina Tavares De Araújo7

1Department of Speech and Language Pathology, Brazil

2Clinical Speech Therapist, Brazil

3Clinical Speech Therapist, Brazil

4Master, Clinical Speech Therapist, Brazil

5Department of Speech and Language Pathology, Brazil

6Department of Medicine, Brazil

7Department of Speech and Language Pathology, Brazil

Brenda Carla Lima Araújo Department of Speech and Language Pathology, Brazil.

Received Date: October 16, 2018; Published Date: November 14, 2018

Abstract

Objectives: To verify the validity of clinical assessment in diagnosing dysphagia in children with chronic encephalopathy. Methods: We included 93 clinical swallowing exams associated with video fluoroscopy performed in children diagnosed with chronic encephalopathy, aged between two and five years, from an institution’s database from March 2010 to September 2011. Evaluations were performed on two separate occasions, by different researchers under blind conditions.

Results: Clinical assessment presented low sensitivity (65,4%) and a positive predictive value (59,6%) in relation to video fluoroscopy for diagnosing dysphagia with liquid consistency. Specificity was low, with levels under (47.9%) for the consistencies tested. A weak concordance was observed (Kappa 0.2) between the clinical assessment and videofluoroscopy for pasty consistency. No statistically significant difference was observed between the studied methods (p>0.05).

Conclusion: In the present study, the sensitivity and specificity of the clinical diagnosis of dysphagia have demonstrated that this diagnostic procedure may not detect any change in the swallowing process, irrespective of the consistency used during investigation.

Keywords: Swallowing disorders; Videofluoroscopy; Cerebral palsy; Sensitivity and specificity; Clinical diagnosis

Introduction

Young children with chronic encephalopathy present motor and postural disorders involving several body parts due to neurological impairment, thus compromising oral motor structures. This may result in changes to the function of eating and dysphagia [1-5].

Dysphagia is diagnosed through clinical and instrumental assessment using subjective and objective parameters in order to characterize and differentiate between normal and abnormal eating behaviour. It has been observed in clinical investigations that there is a need for an accurate diagnosis of dysphagia, with relevant information regarding the therapeutic process.

Clinical assessment of swallowing is essential for recommending guidelines for safe eating without the risk of aspiration, and rehabilitation strategies [6]. However, one weakness involved in the clinical assessment of swallowing is the lack of objectivity, as it may not be possible to accurately determine any changes taking place in the phases of swallowing [6-8]. This may lead to doubts regarding the aspiration of food and/or saliva. Thus, it is necessary to investigate these changes through complementary methods according to each specific clinical scenario [9].

Thus, videofluoroscopy is a complementary method for the diagnosis of dysphagia, since it provides real-time images of all phases of swallowing, therefore allowing a more accurate analysis. This test is considered gold standard for the investigation of swallowing disorders [10]. Authors have emphasized the importance of this method for diagnosing and treating dysphagia within the paediatric population [11-12].

Studies involving clinical assessment and video fluoroscopy have demonstrated methodological limitations (sample selection criteria, definition of age in the study population and a lack of standardization for the consistencies, the posture of the subject and the use of the tools) that may interfere with the performance, the results and the comparison of these methods, thus impeding a careful assessment of what to recommend for an appropriate diagnosis of dysphagia in paediatric patients. It is important to define the accuracy of clinical assessing dysphagia in order to ensure an established clinical diagnosis, and to recommend complementary assessment by video fluoroscopy for greater accuracy.

The aim of this study has been to verify the validity of clinical assessment in diagnosing dysphagia in young children with chronic encephalopathy in comparison with video fluoroscopic swallowing study, using standardized protocols regarding food consistency, utensils and patient posture for the two assessments.

Methods

The present study is characterized by being a cross-sectional retrospective clinical type, performed through the analysis of the database of the Hospital das Clinicals of the Federal University of Pernambuco from approved project by the Ethics Committee for Research on Human Beings at the Center of Sciences of Health of the institution (Protocol No. 108/2011). It is noteworthy that all legal representatives were informed and signed the Free and Informed Consent Form.

The data set was composed of a sample of 93 young children (aged 2 to 5 years; 60.2% male) diagnosed with chronic encephalopathy, for whom children with cerebral palsy, psychomotor retardation and / or neuromotor dysfunction were considered, regardless of severity. Children with orofacial malformations and / or gastric varices were excluded.

The phases of swallowing were clinically assessed using a standardized protocol, during food consumption with liquid and pasty consistencies, using cervical auscultation with a stainlesssteel stethoscope for new born babies (Mikoto’s®, São Paulo, Brazil), positioned on either side of the thyroid cartilage. The person responsible for the child was requested to offer food in the same manner as at home, in an attempt to reproduce routine behaviour patterns for both the person responsible and the child. Observation of feeding took place with a standardized portion of 50 ml carton juice + 5g of instant food thickener for a pasty consistency and 50 ml carton juice for liquid consistency. Food was offered with a plastic cup and spoon for both the pasty and liquid consistencies, respectively. All complications that suggested clinical signs of laryngeal penetration and/or aspiration, which occurred during and at the end of assessment, were noted, such as crying, coughing, choking, vomiting, drowsiness, dyspnoea and any vocal change. Clinical assessments followed a sequence of pasty consistency followed by liquid, conducted by two speech therapists who were not involved in the study, and trained in the Bo bath neuroevolutionary concept, with over 10 years of experience in assessing and rehabilitating children with neurological disorders.

The analysis of the exams of video fluoroscopic swallowing was performed according to standardized protocol. The examinations were performed using a remote-controlled serigraph (VMI - Sterigmatic Pulsar Plus®, Lago Santa, Brazil), with a table tilted at 90° [13-15]; The radiological incident used was a profile, which provides clear visibility of the permeation of the airways. The focus of the fluoroscopic image in the lateral position was delimited by: 1) the anterior region, by the lips, 2) the superior region, by the nasal cavity, 3) the posterior region, by the cervical spine, and 4) the inferior region, by the bifurcation of the airways and the cervical oesophagus. (1g/ml) for contrast, as recommended for fluoroscopic studies of the upper digestive tract. The examination was performed by a speech therapist, with the relevant qualifications and six years of experience performing this examination, and a radiologist. The time-lapse between clinical assessment and the video fluoroscopic swallowing study ranged from seven to twenty days, according to the availability of the child.

Parameters assessed were: movement of the tongue (repetitive piston-like movement (wave) in the anteroposterior direction necessary to propel the bolus into the oral cavity), propulsion of the bolus (transference of the bolus to the posterior region of the mouth through pressure from the oral cavity towards the oropharynx), laryngeal elevation (lifting movement towards the anterior hyoid bone and the larynx) and aspiration (material enters beyond the laryngeal ventricle, reaching the lower airways, which may occur before, during or after swallowing, with or without a protective cough). Dysphagia was defined by the presence of isolated aspiration or by at least two inappropriate parameters, both in the clinical assessment and the videofluoroscopic swallowing study [16].

The study followed the guidelines of the STARD checklist [17]. The validation of clinical assessment in diagnosing dysphagia, using a video fluoroscopic swallowing study as gold standard, was expressed by the calculations of sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value and negative predictive value, with the respective confidence intervals of 95%. The presence of aspiration and penetration in the two assessment methods were also compared.

Statistical analysis was undertaken with the Chi-squared test, using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences 13.0 (SPSS for Windows), considering a p-value < 5% for the acceptance of statistical significance.

Result

In the initial clinical assessment, it was observed that 43.0% of the children demonstrated verbal comprehension, 53.5% interacted with some form of communication and 52.7% presented wheezing. With regard to eating, 49.5% received an exclusively oral diet, with reports of choking while being fed, 95.7% mostly received a menu with a pasty consistency. A total of 68.8% either ate or received food sitting on the lap of an adult.

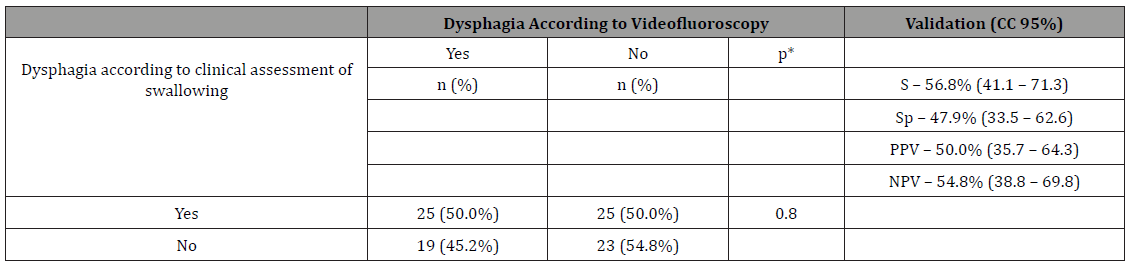

Clinical assessment of pasty consistency (Table 1) presented low sensitivity for the detection of dysphagia.

Table 1: Validation of The Clinical Diagnosis Of Dysphagia With A Pasty Consistency According To The Video fluoroscopic Swallowing Study.

S – Sensitivity

Sp – Specificity

PPV – Positive predictive value

NPV – Negative predictive value

Table 1-Validation of the clinical diagnosis of dysphagia with a pasty consistency according to the video fluoroscopic swallowing study.

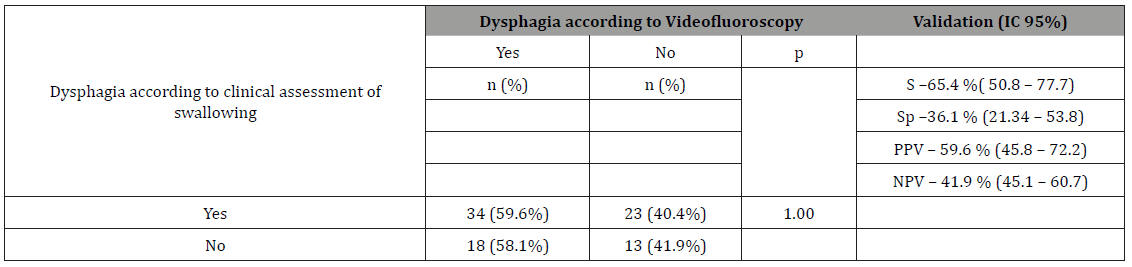

There was a higher sensitivity in the clinical diagnosis of dysphagia for a liquid consistency (Table 2), although at a low level. It is important to highlight the higher positive predictive value for a liquid consistency.

Table 2: Validation of The Clinical Diagnosis of Dysphagia with A Liquid Consistency According to The Video fluoroscopic Swallowing Study

S – Sensitivity

Sp – Specificity

PPV – Positive predictive value

NPV – Negative predictive value

Table 2: Validation of The Clinical Diagnosis of Dysphagia with A Liquid Consistency According to The Video fluoroscopic Swallowing Study

Table 2-Validation of the clinical diagnosis of dysphagia with a liquid consistency according to the video fluoroscopic swallowing study.

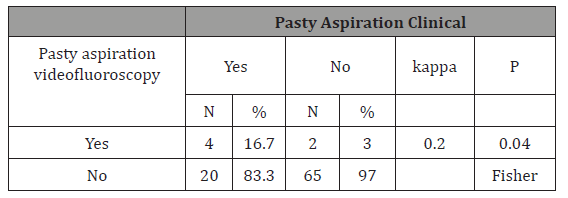

Table 3-demonstrates the comparison between the clinical assessment of swallowing and video fluoroscopy for penetration/ aspiration with a pasty consistency.

Table 3: Penetration/Aspiration with A Pasty Consistency

Discussion

The results have indicated that clinical assessment may not be sufficient to accurately diagnose dysphagia in some patients. It is therefore probable that changes in swallowing are not being identified and dealt with in a timely manner, thus increasing the risk of gradual worsening. Similar findings have been reported by other authors [18,11], who concluded that clinical diagnosis may not perceive certain difficulties in the process of swallowing. However, these studies were not conducted with robust methodologies, with standardized, constant techniques appropriate for the consistencies used.

The low specificity of clinical assessment suggests that children with normal swallowing patterns (little or no risk of aspiration of saliva and/or food) are not detected. This finding is relevant because, for an instrument that purports to diagnose dysphagia, it is important to be more sensitive and present a satisfactory positive predictive value, since not identifying children at risk of aspiration and specific swallowing difficulties would result in functional impairment of eating, the possibility of recurrent pneumonia, weight loss and less efficient rehabilitation results.

Studies involving children with chronic encephalopathy have demonstrated a greater swallowing impairment with liquid consistencies [19,2,20]. This is possibly justified because the clinical diagnosis of dysphagia’s with this consistency is more easily perceived. On the other hand, it cannot be affirmed, when a child presents difficulties in swallowing with this consistency during clinical assessment, whether dysphagia had occurred for liquids, since this assessment may not be reliable.

Similar findings have revealed [6] children with difficulties in swallowing and aged between zero and 15 years of age. The authors demonstrated a sensitivity of 92.0% for clinical assessment in the diagnosis of aspiration for liquid consistency when compared to video fluoroscopy, the latter being considered gold standard. Other authors [18] have corroborated these findings with research into children with dysphagia, aged between one month and five years. These authors demonstrated sensitivity values of above 90.0% for clinical assessment.

One important aspect that should be emphasized is the fact that although some of the cited studies were not performed exclusively with children or people similar to those involved in this study, the aim of the clinical assessment should have been the diagnosis of swallowing disorders, especially in cases with risk of aspiration, irrespective of the exposed individual or the underlying disease. Our results suggest that children with swallowing difficulties may not be accurately diagnosed when clinical assessment is the only diagnostic method used. Thus, the consequences of this practice suggest very ineffective therapeutic approaches, in that a correct, precise, detailed diagnosis may be the active medium for the process of rehabilitation [21-22]. It should be noted that clinical assessment is extremely important in therapy, especially since it is an active instrument in the management of children with swallowing disorders.

Perhaps for these reasons, most authors agree that clinical assessment of swallowing and video fluoroscopy are diagnostic tools that complement one another, and although they assess the same event, there is a diversity in the assessments with regard to the form (technical instruments, patient’s daily routine) and the moment it is performed (different days, so the clinical symptoms of encephalopathy may interfere with the general health of the patient, making her/him more or less prone to the manipulations inherent in the assessments)[ 2,23-25]. Thus, depending on the degree of swallowing impairment, an accurate clinical diagnosis becomes difficult, thus requiring a more objective examination. A video fluoroscopic swallowing study is a quantifiable, dynamic examination, since it permits the visualization of the entire process of swallowing and is therefore useful in the diagnostic assessment of these patients.

One further important aspect refers to the difficulty in finding studies that have used a similar methodology to the present study. Most studies do not present relevant standardizations for the characteristics of the sample, the consistency of the food, the utensils and manner in which food is offered. Moreover, studies have reported apparently high levels of sensitivity, which counts positively for clinical assessment. However, methodological problems for standard techniques may have contributed to these improved results. Thus, our results may direct a more critical clinical eye over the diagnosis of dysphagia in children, especially in alerting phono audiologists about the need to standardize assessments in their clinical practice for these patients, in order not delay any conduct beneficial to the quality of the patient’s life by erroneously ruling out the presence of dysphagia.

Our results indicated weak concordance (Kappa 0.2) between the methods of clinical assessment and video fluoroscopy for aspiration with a pasty consistency. In this case, clinical assessment alone may not be an effective tool for diagnosing aspiration with this consistency since, once undiagnosed aspiration may harm the health of children with encephalopathy. Moreover, aspiration is an intermittent phenomenon, because a test may demonstrate episodes of aspiration and not others. Besides, it is more difficult to perceive problems in the pharynx, which is sufficient justification for the difficulty in diagnosing swallowing disorders.

Children who composed the sample presented heterogeneous characteristics regarding motor, sensory and cognitive aspects, which may have interfered with the performance of the assessments. However, there is known to be a difficulty in classifying the different types and manifestations of these neurological conditions because motor, cognitive, sensory and overall body posture impairments are changes that are present in varying degrees, which therefore makes the homogeneity of this population problematic. Thus, children with neurological disorders may present changes in the dynamics of swallowing because of the degree of motor impairment, the cognitive level, or even through changes or sensory deprivation, regardless of the type or location of the lesion presented.

Finally, it is important to emphasize complementary diagnosis, since it promotes benefits for the patient, indicates medical conduct and defines the therapy program in an individual manner.

Conclusion

It is concluded that clinical assessment may not detect any changes in the process of swallowing. Thus, video fluoroscopic findings potentialize clinical findings as a complementary method for diagnosing dysphagia.

Acknowledgement

FACEPE: Fundação de Amparo à Ciência e Tecnologia do estado de Pernambuco - Brasil – APQ 0843-4.07/08. CNPq: Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico – Brasil.

Conflict of Interest

No conflict of interest.

References

- Andrew M, Sullivan PB (2010) Feeding difficulties in disabled children. Paediatrics Child Health 20 (7): 321-326.

- Sun Jie, Chein Wei (2016) Correlation studies of barium on pulmonary infection under the assessment of VFSS. Experimental and Therapeutic Medicine 11(2): 435-438.

- Otapowicz D, Sobaniec W, Okurowska-Zawada B, Artemowicz B, Sendrowski K, et al. (2010) Dysphagia in children with infantile cerebral palsy. Advances in Medical Sciences 55(2): 222-227.

- Parkes J, Hill N, Platt M J, Donnelly C (2010) Oromotor dysfunction and communication impairments in children with cerebral palsy: a register study. Dev Med Child Neurol 52(12): 1113-1139.

- Newman R, Vilardell N, Clavé P, Speyer R (2016) Effect of Bolus Viscosity on the Safety and Efficacy of Swallowing and the Kinematics of the Swallow Response in Patients with Oropharyngeal Dysphagia: White Paper by the European Society for Swallowing Disorders (ESSD). Dysphagia 31(2): 232-249.

- Dematteo C, Matovich D, Hjartarson D (2005) Comparison of clinical and videofluoroscopic evaluation of children with feeding and swallowing difficulties. Dev Med Child Neurol 47(3): 149-157.

- Van Den Engel Hoek L, Erasmus CE, Van Hulst KC, Arvedson JC, De Groot IJ, et al. (2014) Children with central and peripheral neurologic disorders have distinguishable patterns of dysphagia on video fluoroscopic swallow study. J Child Neurol 29(5): 646-653.

- Jafer NM, Edmund NG, Wing Fai Au F, Steele CM (2015) Fluoroscopic evaluation of oro-pharyngeal dysphagia: anatomy, technique, and common etiologies. Am J Roentgenol 204(1): 49-58.

- Brodsky MB, Suiter DM, Gonzaléz Fernandéz M, Micthtalik HJ, Frymark TB, et al. (2016) Screening Accuracy for Aspiration Using Bedside Water Swallow Tests A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Chest 150(1): 148-163.

- Lazarus CL. (2017) History of the Use and Impact of Compensatory Strategies in Management of Swallowing Disorders Dysphagia 32(3): 3-10.

- Menezes EC, Santos FAH, Alves FL (2017) Cerebral palsy dysphagia: a systematic review. Rev CEFAC 19(4): 565-574.

- Mcnair J, Reilly S. (2003) The pros and cons of video fluoroscopic assessment of swallowing in children. Asia Pacific Journal of Speech, Language and Hearing 8: 93-104.13 Peterson R. (2018) Modified Barium Swallow for Evaluation of Dyphagia. Dysphagia 89(3): 257–275.

- Ryu JS, Donghwi Park, Kang JY. (2015) Application and Interpretation of High-resolution Manometry for Pharyngeal Dysphagia. J Neurogastroenterol Motil 21(2): 283–287.

- Lagos Guimarães HN, Teive HA, Celli A, Santos RS, Abdulmassih EM, et al. (2016) Aspiration Pneumonia in Children with Cerebral Palsy after Videofluoroscopic Swallowing Study. Int Arch Otorhinolaryngology 20(2): 132-137.

- Kim HM, Choi KH, Kim TW. (2013) Patients radiation dose during videofluoroscopic swallowing studies according to underlying characteristics. Dysphagia 28(2): 153-158.

- Bossuyt PM, Reitsma JB, Bruns DE, Gatsonis CA, Glasziou PP, et al. (2003) Towards complete and accurate reporting of studies of diagnostic accuracy: the STARD initiative. Clinical Chemistry and Laboratory Medicine 49(1): 1-6.

- Santos RRD, Sales AVMN, Cola PC, Jorge AG, Peres FM, et al. (2014) Acurácia da avaliação clínica da disfagia na encefalopatia crônica não progressiva. Rev CEFAC 16(1): 197-201.

- Oliveira DL, Moreira EA, De Freitas MB, Gonçalves JA, Furkim AM, et al. (2017) Pharyngeal Residue and Aspiration and the Relationship with Clinical/Nutritional Status of Patients with Oropharyngeal Dysphagia Submitted to Video fluoroscopy. J Nutr Health Aging 21(3): 336-341.

- Iruthayarajah J, McIntyre A, Mirkowski M, Welch-West P, Loh E, Teasell R (2018) Risk factors for dysphagia after a spinal cord injury: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Spinal Cord.

- Mccullough GH, Wertz RT, Rosenbek JC (2001) Sensitivity and specificity of clinical/bedside examination signs for detecting aspiration in adults subsequent to stroke. Journal of Communication Disorders 34(1-2): 55- 72.

- Terré R, Mearin F (2012) Effectiveness of chin-down posture to prevent tracheal aspiration in dysphagia secondary to acquired brain injury. A videofluoroscopy study. Neurogastroenterol Motil 24(5): 414-419.

- Araujo BCLM, Motta MEA, Castro AG, Araujo CMT (2014) Clinical and videofluoroscopic diagnosis of dysphagia in chronic encephalopathy of childhood. Radiol Bras 47(2): 84-88.

- Almeida ST, Ferlin EL, Maciel AC, Fagondes SC, Callegari Jacques SM, et al. ( 2018) Acoustic signal of silent tracheal aspiration in children with oropharyngeal dysphagia. Logoped Phoniatr Vocol 15: 1-6.

- Garcia Romero R, Ros Anarl I, Romea Montañés MJ, López Calahorra JA, Guitierréz Alonso C, et al. (2018) Evaluation of dysphagia. Results after one year of incorporating videofluoroscopy into its study. An Pediatr (Barc) 89(2): 92-97.

-

Brenda Carla L A, Adriana Guerra De C, Thales Rafael C De M L, Amanda Louize F M, Carlos Kazuo T, et al. Validation of Clinical Assessment for Diagnosing Dysphagia in Infants with Chronic Encephalopathy. On J Otolaryngol & Rhinol. 1(1): 2018. OJOR.MS.ID.000505.

-

Diagnosing Dysphagia, Chronic Encephalopathy, Swallowing Disorders,Videofluoroscopy, Cerebral Palsy, Sensitivity And Specificity, Clinical Diagnosis, Neurological Impairment, Aspiration, Accurate Analysis, Paediatric Patients, Clinical Diagnosis, Psychomotor Retardation, Gastric Varices, Crying, Coughing, Choking, Vomiting, Drowsiness, Neurological Disorders.

-

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.