Case Report

Case Report

Sphenoid Sinusitis Presenting as Cavernous Sinus Thrombosis in a Diabetic Patient

Ali A Almomen1*, Mohammed Al Eid2, Abdullah Ayman Alshakhs 3, Mohammed Al Saeed4, Njood Alaboud5 and Faissal A Al Habeeb3

1Consultant Rhinology & Skull base surgery, King Fahad Specialist Hospital, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia

2 ENT trainee resident, Saudi ORL program, Eastern Region, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia

3Medical intern, King Faisal University, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia

4Sixth year medical student, AlBaha University, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia

5Sixth year Medical student, King Faisal University, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia

Ali Almomen, Consultant Rhinology & skull base surgery, King Fahad Specialist Hospital Dammam, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia.

Received Date: January 14, 2020; Published Date: January 28, 2020

Abstract

This article reports a case of isolated left sphenoid sinusitis with the presentation of cavernous sinus thrombosis as a complication in a 60 years old diabetic female, we present the case history, significant physical findings, radiological investigations and discuss relevant anatomy, pathogenesis, diagnostic evaluation and treatment.

Introduction

Isolated sphenoid sinusitis is a very rare and potentially lifethreatening occurrence. Because of its rarity, its true incidence is difficult to establish, but it lies within the range of 2.7% to 8% based on larger series [1-3]. The incidence of isolated fungal disease is even lower. sphenoid sinusitis represents a challenge diagnostically as it does not present in a similar way to inflammation of the other paranasal sinuses, presenting symptoms being generally nonspecific [4].

Streptococcus pneumonia and Hemophilus influenza account for more than 50% of bacterial acute sinusitis. Fungi are also possible pathogens involved in sinusitis, notably Aspergillus. The invasive forms of mycotic diseases of the sinuses, and particularly the fulminant forms, are potentially fatal. Isolated aspergillosis of the sphenoid sinus or the clivus is a difficult diagnosis, since the often-misleading clinical manifestations of this rare disease develop late. These patients become apparent by neurological signs such as cavernous sinus syndrome, pseudotumor of the pituitary or the orbit. The invasive forms are usually observed in immune compromised patients. Diagnosis is often made intra-operatively or on histological examination.

Case Report

An 60 years old female, known case of Hypertension, Diabetes Mellitus. She presented to the emergency department with a 6 days history of headache, abdominal pain associated with nausea and vomiting and fever. There was also history of left ear pain and tinnitus for 2 months, and history of recurrent sinusitis.

She also had positive history of meningitis. And surgical history for the right eye. Her Initial admission and evaluation were to rule out acute coronary syndrome as she had risk factors and her initial Troponin was positive, but serial ECG and cardiac enzymes were negative. 8 hours later she developed ecchymoses and proptosis in the left eye, the ophthalmologist was consulted and ordered Brian CT, orbital MRI and MRA, which were suggestive of cavernous sinus thrombosis and left superior ophthalmic vein thrombosis , she was then shifted to ICU and started on Meropenem , Vancomycin, Amphotericin B and Enoxaparin and her symptoms improved and she was shifted to the medical ward.

Later she developed dysphagia and signs of lower motor neuron facial palsy , brain MRI , MRA and MRV were performed and showed interval partial resolution of ophthalmic vein and cavernous sinus thrombosis and interval increase in the thickness of sphenoid sinus with persistent low signal and Meningeal/extra axial likely inflammatory process reflected over the left CP angle and mid brain with loculations. so, she was transferred to King Fahad Specialist hospital in Dammam for further management. Upon arrival to our hospital she was vitally stable , conscious, alert and oriented , she had limited right eye abduction and non-reactive pupil, closure of the left eye was weak and left nasolabial folds were flat, her gag reflex was absent bilaterally and her tongue was deviated to the right side, the elevation of the uvula was weak .

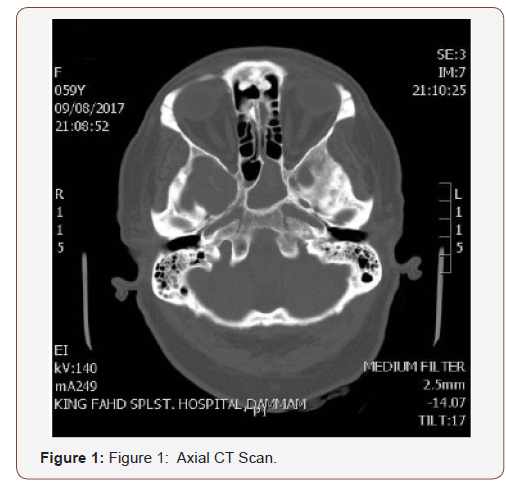

Endoscopic sinus surgery was performed and the left sphenoid sinus drained pus and mucin, which was sent for bacterial and fungal culture but failed to show growth. Post op the patient clinically improved and MRI showed interval resolution of the hyperintense contents with mild residual mucosal thickening in the left sphenoid sinus and marked reduction of the previously seen left sided posterior fossa epidural empyema with minimal residual thickening, the cavernous sinus showed no residual thrombosis (Figure 1).

The left sphenoid sinus is opacified with central hyperdense material likely high proteinaceous material and evidence of chronic sinusitis and no bony erosions of defect, minimal opacification of right sphenoid sinus, under pneumatized frontal sinuses are noted.

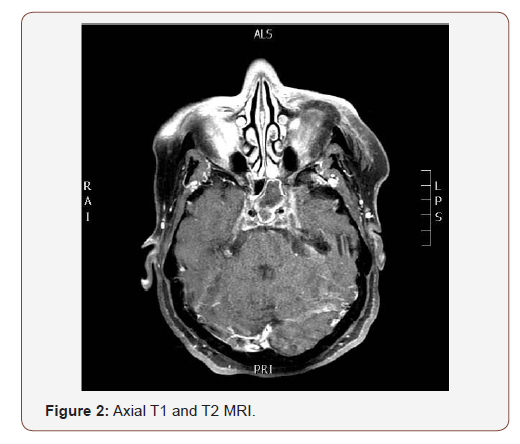

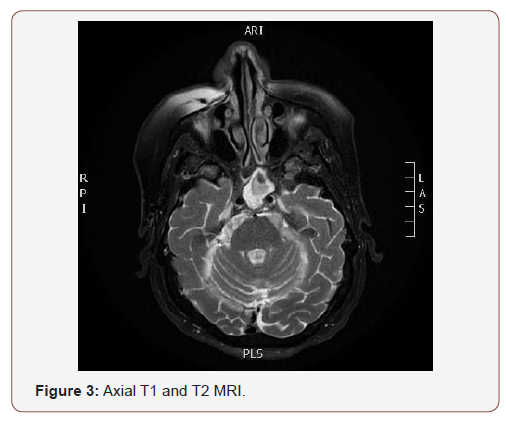

(Figures 2,3) The left sphenoid sinus shows filling by material restricted on diffusion consistent with pus and acute sinusitis. Also, restriction on diffusion is noted at left cerebellopontine angle, anterior to medulla oblongata, and occipital horn of both lateral ventricles. the overall picture is likely representing meningitis and ventriculitis that could spread from infected sphenoid sinus.

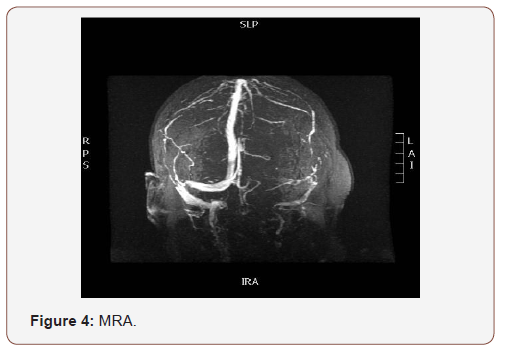

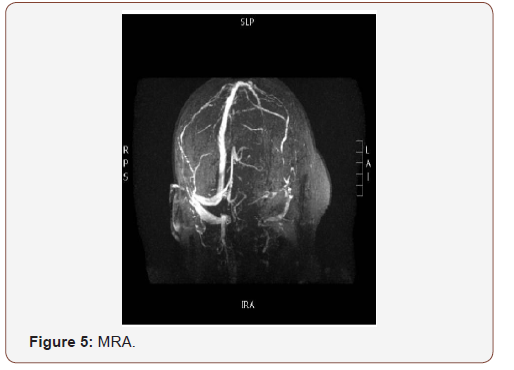

(Figures 4,5) The superior ophthalmic vein shows asymmetrical bilateral dilatation with filling defect more at left side suggestive of thrombosis, cavernous sinus thrombosis cannot be excluded.

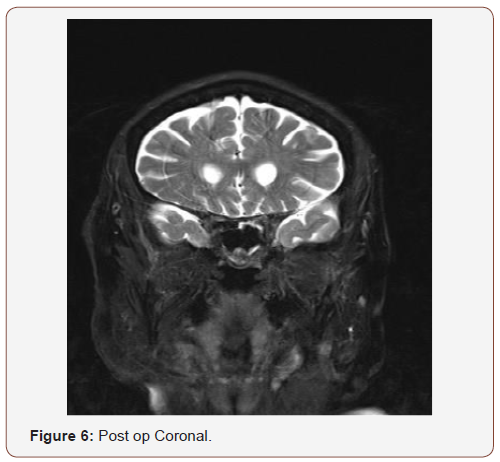

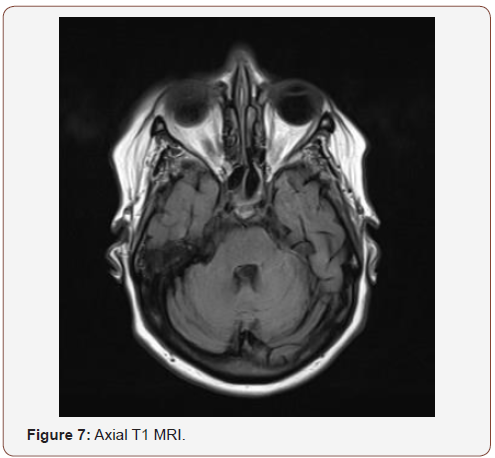

(Figures 6,7) interval resolution of the hyperintense contents with mild residual mucosal thickening in the left sphenoid sinus and marked reduction of the previously seen left sided posterior fossa epidural empyema with minimal residual thickening, the cavernous sinus showed no residual thrombosis.

Discussion

Sphenoid sinusitis present with non-specific symptoms which sometimes can delay our diagnosis and lead to a potentially lethal situation [1]. The usual presenting features are indeed complications of the sinusitis itself due to the proximity of sinus to cavernous sinus and orbit. The sphenoid sinus located at the Centre of the head. It’s absent in only 1% to 1.5% of the population [2]. Due to its location, the presenting symptoms of sphenoid sinusitis are non-specific and it’s not possible to do optimal clinical examination due to its relative inaccessibility [3]. The most common presenting features of sphenoid sinusitis are headache and facial pain. It may also include rhinorrhea and less frequently, nasal congestion [4]. Headaches can usually localize at the vertex of the skull [1].

The sphenoid is bounded Superiorly by the pituitary gland, optic nerve with its chiasma and middle cranial fossa; anteriorly bounded by the pterygoid canals, nasopharynx, nerves, and the pteropalatine ganglion and artery; laterally it bounded by the internal carotid artery, cavernous sinus, and cranial nerves III, IV, V1, V2 and VI [5,6]. Any infection in the sphenoid sinus can lead to severe complications, because of its location deep within the skull base. The most common complication of sphenoid infection is meningitis. Less frequently, cavernous sinus thrombosis and orbital complications such as orbital cellulitis, periorbital cellulitis, orbital abscess and subperiosteal abscess can result [1].

The technique for the intracranial approach of sphenoid sinusitis is either by direct lateral extension through nasal mucosa and thin diploic bone, or via thrombophlebitis of the emissary veins draining into the cavernous sinus [7,8]. There are many features associated with cavernous sinus thrombosis. Chemosis, preseptal oedema, and proptosis are the most common early signs of venous congestion observed [8,9,10,11]. Subsequently, some patients may develop diplopia due to limitations of extraocular muscle movement. Meningism us is also very common and has been documented in 40% of patients [10]. After 48h, bilateral ocular findings become evident as the communicating intercave nous veins allow the propagation of thrombophlebitis [9,10]. Late complications include cortical venous thrombosis, pituitary insufficiency, and subdural, epidural, or parenchymal abscesses [12].

Currently, CT and MRI consider the best confirmatory test of cavernous sinus thrombosis. MRI using magnetic resonance venography and flow parameters consider more sensitive than CT for the evaluation of cavernous sinus thrombosis. The most common direct radiographic signs include convexity of the normally concave lateral wall, expansion of the cavernous sinus, asymmetry and abnormal irregular filling defects. Indirect signs relate to dilation of the superior ophthalmic vein, exophthalmos, venous obstruction, sinus tributaries to the cavernous sinus and thrombi in the veins.

Empiric antibiotic regimens should be chosen based on the the most common pathogens, that depend on the source of infection, such as sinusitis, facial cellulitis, or dental abscesses. While awaiting culture results, antibiotic therapy should consist of metronidazole, third-generation cephalosporin and nafcillin. Vancomycin can be used instead of nafcillin if the risk of methicillin resistance is high [11,13,14].

The use of steroids in the management of cavernous sinus thrombosis is controversial. The benefits of decreasing cranial nerve edema, orbital inflammation, intracerebral hemorrhage and vasogenic edema must be weighed against the potential immunosuppressive effects and possible prothrombotic properties. Up to date, there is no validated literature to support the improved outcome using steroids, although there are reports of improved cranial nerve function secondary to decreased inflammation [8,15,16].

The role of anticoagulation in the management of cavernous sinus thrombosis is also controversial [8,14]. The proposed benefit is the reduction of thrombus progression in the septic CST. Bacteria may reside within a thrombus for a period until canalization of the thrombus occurs, allowing for the penetration of antibiotics. Most surgical therapies are directed toward eradicating the inciting infection. When dealing with sinusitis-associated cavernous sinus thrombosis, functional endoscopic sinus surgery directed at the affected sinus has been shown to improve outcomes when performed early [12].

Acknowledgement

None.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interests.

References

- Hsu YC, Su CY, Hsu RF, Kuo FY, Hsieh MJ (2003) Abducens palsy in acute isolated sphenoid fungal sinusitis. J Otolaryngol 33: 319-321.

- Grenwald L (1925) Descriptive and topor graphic anatomy of the nose and its sinuses. In: Thinker A, Kahler O (eds.), Diseases of the airways and oral cavity. Berlin: Springer/M? Nchen: Bergmann S1-95.

- Sethi DS (1999) Isolated sphenoid lesions: diagnosis and management. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 120(5): 730-736.

- Friedman A, Batra PS, Fakhri S, Citardi MJ, Lanza DC (2005) Isolated sphenoid sinus disease: etiology and management. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 133: 544-550.

- Ada M, Kaytaz A, Tuskan K, Guvenç MG, Selçuk H (2004) Isolated sphenoid sinusitis presenting with unilateral VIth nerve palsy. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol 68: 507-510.

- Wang ZM, Kanoh N, Dai CF, Kutler DI, Xu R, Chi FL, et al. (2002) Isolated sphenoid sinus disease: an analysis of 122 cases. Ann Otol Rhino Laryngol 111: 323-327.

- Kim SW, Kim DW, Kong IG, Kim DY, Park SW, et al. (2008) Isolated sphenoid sinus diseases: report of 76 cases. Acta Otolaryngol 128: 455-459.

- Bhatia K, Jones NS (2002) Septic cavernous sinus thrombosis secondary to sinusitis: are anticoagulants indicated? A review of the literature. J Laryngol Otol 116: 667-676.

- Cannon ML, Antonio BL, McCloskey JJ, Hines MH, Tobin JR, et al. (2004) Cavernous sinus thrombosis complicating sinusitis. Pediatr Crit Care Med 5: 86-88.

- DiNubile MJ (1988) Septic thrombosis of the cavernous sinuses. Arch Neurol 45: 567-572.

- Southwick FS, Richardson EP, Swartz MN (1986) Septic thrombosis of the dural venous sinuses. Medicine (Baltimore) 65: 82-106.

- Younis RT, Lazar RH (1993) Cavernous sinus thrombosis: successful treatment using functional endonasal sinus surgery. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 119: 1368-1372.

- Yarington CT (1977) Cavernous sinus thrombosis revisited. Proc R Soc Med 70: 456-459.

- Ebright JR, Pace MT, Niazi AF (2001) Septic thrombosis of the cavernous sinuses. Arch Intern Med 161: 2671.

- Keane JR (1996) Cavernous sinus syndrome. Analysis of 151 cases. Arch Neurol 53: 967-969.

- Solomon OD, Moses L, Volk M (1962) Steroid therapy in cavernous sinus thrombosis. Am J Ophthalmol 54: 1122-1124.

-

Ali A Almomen, Mohammed Al Eid, Abdullah Ayman Alshakhs, Mohammed Al Saeed, Njood Alaboud, Faissal A Al Habeeb. Sphenoid Sinusitis Presenting as Cavernous Sinus Thrombosis in a Diabetic Patient. On J Otolaryngol & Rhinol. 2(1): 2020. OJOR.MS.ID.000530.

-

Sphenoid sinusitis, Cavernous sinus, Streptococcus pneumonia, Aspergillus, Hypertension, Cavernous sinus, Headache, Nasal congestion, Cranial nerves, Parenchymal abscesses.

-

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.