Research Article

Research Article

Single-Stage Drug-Induced Sleep Endoscopy, Nasal Surgery and Modified Barbed Soft Palatal Posterior Pillar Flap Palatopharyngoplasty for Treatment of Obstructive Sleep Apnea

Ahmed Mohamed Mohye El Din Elbassiouny*

Professor of Otolaryngology, Faculty of Medicine, Cairo University, Egypt

Ahmed Mohamed Mohye El Din Elbassiouny, Professor of Otolaryngology, Faculty of Medicine, Cairo University, Egypt.

Received Date: February 03, 2020; Published Date: February 13, 2020

Abstract

Objective: To investigate the overall efficacy of a single-stage surgical procedure based on localizing the site of anatomic obstruction with simultaneous combined nasal-palatopharyngeal surgery for the treatment of OSA.

Methods: A total of 35 consecutive OSA patients were enrolled in the study. All patients had OSA, were type I Fujita classification, stage 1 or 2 Friedman classification and had nasal septal deviation and inferior turbinate hypertrophy. Intraoperative drug-induced sleep endoscopy (DISE) was performed in all patients. Modified barbed palatopharyngoplasty with septoplasty and reduction of the size of inferior turbinate were used to correct the upper airway abnormalities. Baseline and 6 months postoperative overnight portable polysomnography was performed. Surgical results (Subjective symptoms improvement, reduction of OSA), patient satisfaction, complications were recorded. Surgical success was defined as a reduction of at least 50% in the preoperative apnea-hypopnea index (AHI) and a final AHI of less than 20 per hour.

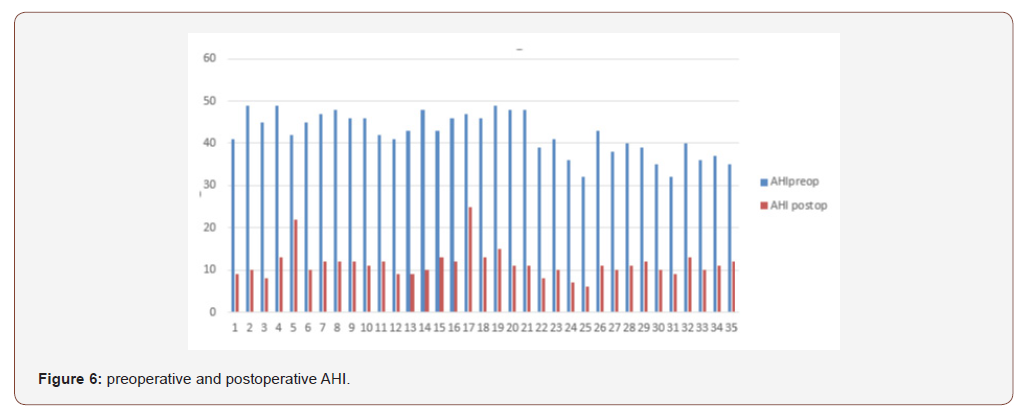

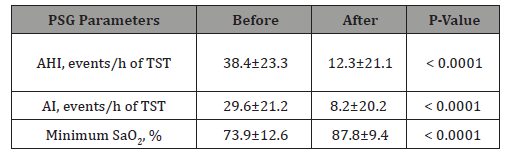

Results: The Surgical success was 89% (31/35) of patients, 26 males, and 9 females. Snoring was improved with a snoring scale reduced from 9.4±2.8 to 1.07±0.3 (p<0.0001). The nasal blockage was improved with the nasal Obstruction Visual Analog Scale from 8.6±1.3 to 0.57±0.2 (p<0.0001). The Epworth Sleepiness score (ESS) was decreased from 8.9±1.3 to 1.11±0.2(p< 0.0001). The pre-operative to post-operative AHI statistically improved from 38.4±23.3 to 12.3±21.1 (p <0.0001) and lowest O2 saturation from 73.9±12.6% to 87.8±9.4%(p<0.001). There were no significant complications. All patients were satisfied with the single-stage treatment.

Conclusion: Our data indicate that Single-staged modified barbed soft palatal posterior pillar flap palatopharyngoplasty with nasal surgery is a safe, effective. It has the potential to serve as an effective alternative for the staged surgery without adding to the cost-effectiveness in terms of total hospitalization.

Keywords: Single stage; Nasal surgery; Palatopharyngeal surgery; Drug induced sleep endoscopy; OSA

Introduction

Obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) is a disorder caused by the repetitive collapse of the upper airway during sleep that may occur at any level including the nasal cavity, nasopharynx, oropharynx, and hypopharynx, and may be either single-level or multilevel. Data from observational studies suggest that nasal obstruction contributes to the pathogenesis of snoring and OSA [1]. In most studies, nasal obstruction is partially related to the development | or aggravation of OSA [2,3]. Nasal obstruction is related to OSA in several ways:

1. Increasing upper airway resistance as nasal obstruction can cause an increase in negative pressure in the upper airway and induces an inspiratory collapse at the pharyngeal level.

2. Patients become mouth breathers during sleep, which destabilizes the upper airway and aggravates sleep-related breathing disorder.

3. Interferes with the nasal reflexes that stimulate ventilation [4].

Data on OSA patients treated for nasal obstruction alone has shown consistent improvement in subjective symptoms such as daytime somnolence and snoring despite a minimal change in their sleep study results [5]. However, in other words, the effect of nasal surgery alone in sleep-disordered breathing (SDB) with nasal obstruction is controversial [6,7]. Nasal surgery alone has also been shown to significantly improve CPAP tolerance and adherence [8].

Obstruction at the level of the soft palate, pharynx, and tonsillar pillars is a more common finding in patients with snoring and OSA. These sites are the focus of many of the surgical procedures traditionally labeled phase I therapies. Soft palatal procedures serve to reduce or reconstruct the collapsible portions of the soft palate. Recently, there has been a paradigm shift within the field of sleep surgery in recent years with an emphasis on mucosalsparing reconstruction of the soft palate rather than ablation [9]. Surgical management of retropalatal airspace obstruction now focuses on the concept of lateral pharyngeal port opening [10- 12]. The complete lateral oropharyngeal collapse was significantly associated with increased severity of OSA. The complete concentric collapse of the velum and complete lateral oropharyngeal collapse were associated with higher BMI values [13].

The success of airway surgery depends on an accurate diagnosis of the sites of obstruction and the appropriate selection of procedures to address these sites. Drug-induced sleep endoscopy (DISE) is one of the cornerstone procedures that help to identify the site of the upper airway obstruction. Rather than applying a standardized approach to the surgical management of OSA, it seems preferable to tailor treatment to the specific needs of each patient [14,15].

Generally, there is growing evidence that supports the effectiveness of multiple site surgery to effectively treat snoring and OSA. These sites of upper airway obstruction have often been treated in the past independently and understanding of these problems would suggest multilevel treatments to provide more significant results than focusing on single-site procedures. However, an algorithm for determining the optimal surgical approach, such as a single-stage or multistage approach, in OSA patients with suspected simultaneous oropharyngeal and nasal obstructions is not well established. Furthermore, there is minimal information on the efficacy of single stage palatopharyngeal surgery with nasal surgery for OSA with nasal obstruction [16,17]. The author has undertaken this study to evaluate the clinical efficacy and patient satisfaction of single stage modified barbed soft palatal posterior pillar flap palato pharyngoplasty with nasal surgery for the treatment of OSA patients.

Materials and Methods

Study design

Single-center prospective uncontrolled case series.

Subjects

Following the approval of the Institutional Review Board and the appropriate informed consent of patients, 35 patients who met inclusion criteria and complaining primarily from nasal blockage, snoring and symptoms suggesting OSA were included in this study between April 2015 and January 2019.

Inclusion criteria

Patients were included in this study when they met the following criteria:

1) Age ≥18 years

2) Loud disruptive snoring with a total ESS score of 10 or more.

3) Documented OSA by portable polysomnography.

4) Showed obstructing nasal conditions (nasal septal deviation, inferior turbinate hypertrophy) on Clinical examination, nasal endoscopy, and imaging, with no evidence of nasal valve collapse or craniofacial abnormalities.

5) Type I Fujita classification, stage 1 or 2 Friedman classification with significant palatal redundancy and soft palatal posterior pillar webbing.

6) No improvement with previous medical treatment for nasal obstruction.

7) No previous history of surgical therapy for OSA.

8) Had refused or were unwilling to accept continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) or oral appliance as a permanent solution.

9) Drug-induced sleep endoscopy (DISE) revealed the collapse of the soft palate, the lateral pharyngeal wall and/or the tonsils and a non-collapsing tongue base.

10) BMI<35 kg/m2.

Subjective Symptoms

A complete medical history was recorded by completion of a questionnaire regarding subjective symptoms including snoring and nasal blockage. Nasal Obstruction Visual Analog Scale (NOVAS) was used to determine the degree of nasal obstruction using a continuous scale from 0 to 10 in which 0 corresponds to no obstruction and 10 corresponds to complete obstruction [18]. A visual analog scale (VAS) was used to determine the degree of snoring using a continuous scale from 0 to 10, where 0 indicated no snoring and 10 indicated maximum snoring. An 8-item Epworth Sleepiness Scale with scores for each item ranging from 0 to 3 points was used to determine the level of daytime sleepiness. A total ESS score of 10 or more is considered to represent pathological sleepiness. Thus, the final ESS score could range from 0(minimum) to 24(maximum) and a score of 10 or more is considered to represent pathological sleepiness. All postoperative questionnaires were recorded 6 months after. Body mass index was measured in all cases.

Upper Airway Examination

Complete otorhinolaryngological examination including flexible nasopharyngoscopy was performed for all patients. Tonsil size (TS) and Tongue position (TP) were graded and Mallampati score was recorded and all patients were staged based on the staging system described by Friedman et al [19].

TS was graded from 1 to 4 as follows:

1. Tonsils hidden within the pillars

2. Tonsils extending to the pillars.

3. Tonsils beyond the pillars but not to the midline

4. Tonsils extending to the midline.

TP was also graded from 1 to 4 as follows:

1. The entire uvula and tonsils or pillars are visible.

2. The uvula but not the tonsils are visible.

3. Only the soft palate is visible.

4. Only the hard palate is visible.

Drug-Induced Sleep Endoscopy (DISE)

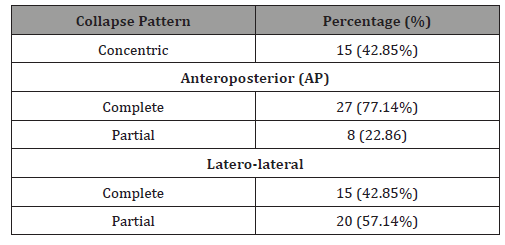

Drug-induced sleep endoscopy (DISE), according to Kezirian EJ et al [15], was performed in all cases to localize the site of upper airway collapse. DISE was performed using propofol targetcontrolled infusion (TCI) with the guidance of a Bispectral Index monitor (BIS). One of the main advantages of propofol consists of rapid sedation induction and a quick metabolization [20]. Literature data reported a direct relation between propofol concentrations increased and upper airways collapsibility and decreasing genioglossus muscle tone. These effects are dose-dependent, highlighting the importance of administrating as lower dosage of propofol as possible, and the importance of performing DISE using target-controlled infusion (TCI) systems, which represent the preferred option for infusion (starting dose: 1.5-3.0 μg/ml; increasing rate 0.2-0.5, x times until the sedation level at right observation window have been obtained) [21]. During DISE, the level (palate, oropharynx, tongue base, hypopharynx/epiglottis), the direction (anteroposterior [AP], concentric, lateral), and degree of upper airway collapse (none, partial, or complete) were scored. The palate is defined as the portion of the upper airway at the level of the soft palate and uvula, while the oropharynx is defined by the pharyngeal region at the levels of the tonsils (above the tongue base). The tongue base is defined as the retroglossal area, and the hypopharynx is defined as the upper airway region below the tongue base, including the tip of the epiglottis.

Polysomnography

Portable polysomnography (ResMed’s Apnea Link™ Plus) was used to diagnose possible OSA. The AHI was from the Apnea Link Plus signal data. Respiratory events were scored using definitions established by the American Academy of Sleep Medicine and hypopneas were scored using the “recommended” definition. OSA was defined as an AHI greater than or equal to 5 [22].

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using the paired t-test. Data are displayed as means (+/-) standard deviation (SD). Statistical significance was accepted when p<0.05.

Surgical Procedure

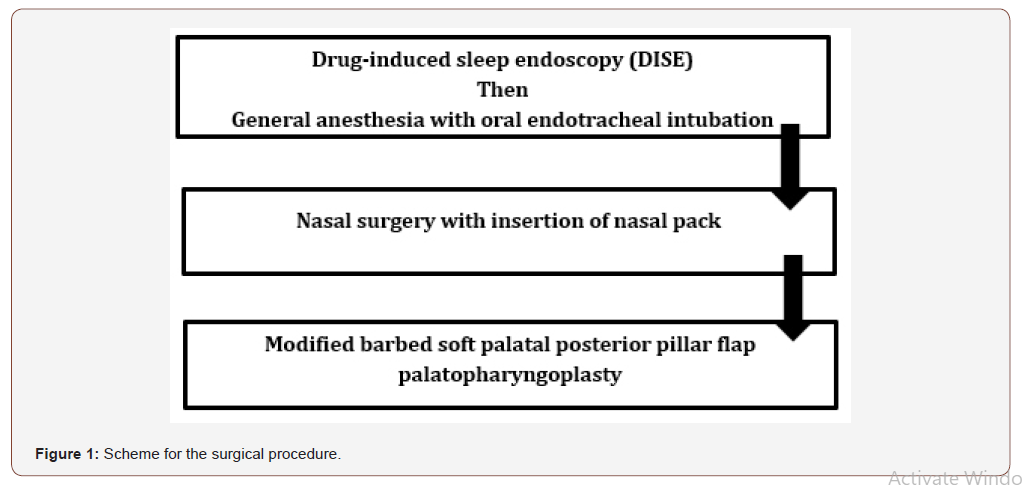

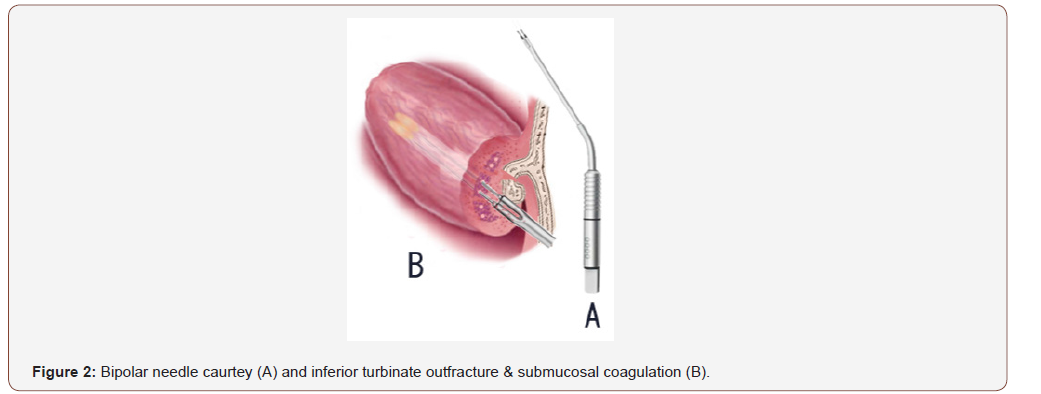

All patients with OSA and nasal obstruction were treated with modified barbed soft palatal posterior pillar flap palato pharyngoplasty and nasal surgery. DISE was performed before the induction of general anesthesia. Nasal surgery was done before the modified barbed soft palatal posterior pillar flap palato pharyngoplasty (Figure 1). Nasal surgery was including septoplasty and inferior turbinate submucosal coagulation using a bipolar needle caurtey with a turbinate outfracture to get more wider nasal airway (Figure 2). After nasal surgery, nasal packing was done with rapid rhino nasal packs which were removed after 24 hours after surgery.

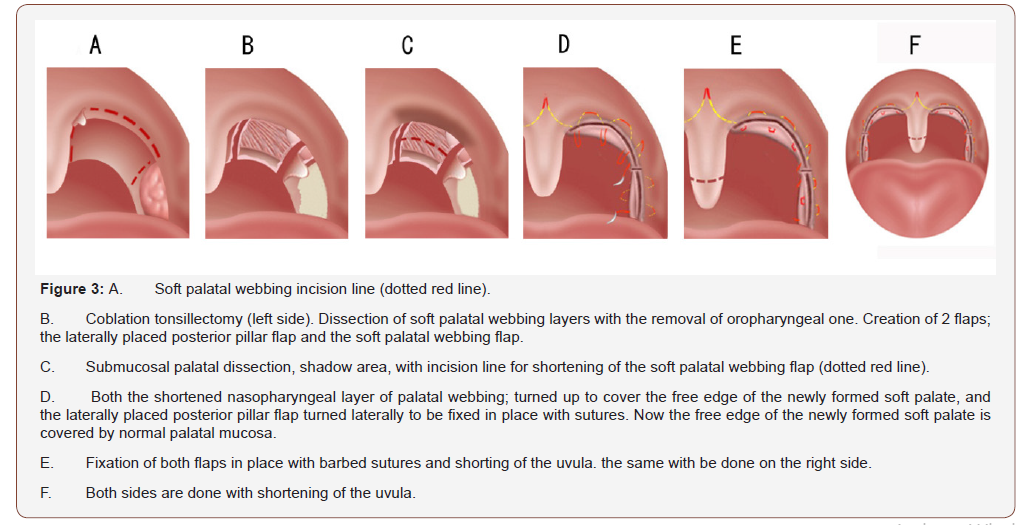

All modified barbed soft palatal posterior pillar flap palato pharyngoplasty procedures were carried out under general anesthesia with oral endotracheal intubation according to the surgical technique described by the author [12] (Figure 3). This technique was designed to surgically treat patients with all tonsillar grades in addition to the soft palatal and lateral pharyngeal wall collapse diagnosed during DISE in patients with snoring and OSA.

In summary, the surgical steps include:

1. Local infiltration anesthesia with epinephrine 1: 200,000 in the space between the two mucosal layers of the palatal webbing.

2. An incision was done in the ventral layer of the palatal webbing to separates both layers (Figure 3A).

3. Coblation-assisted extracapsular tonsillectomy. The ventral mucosal layer of the webbing is removed down to its free border. Using the Evac 70 wand, the nasopharyngeal mucosal layer is released on both sides to separate it from the uvula, medially, and the posterior pillar, laterally. The lateral release incision is extended to the most lateral end of the posterior pillar so cutting in its way the whole fibers of the palatopharyngeus muscle. Two flaps are now available; the laterally placed one which represents the posterior pillar up to the lateral release incision and the free webbing flap created after medial and lateral release incisions (Figure 3B).

4. The dorsal mucosal layer of the palatal webbing is shortened, of 4-5mm in length with submucosal palatal dissection above the free border of the soft palate (Figure 3C).

starting from the midline of the soft palate 1 cm above the uvula, the shortened dorsal mucosal layer is turned up to cover the free edge of the soft palate and then fixed in place on both sides.

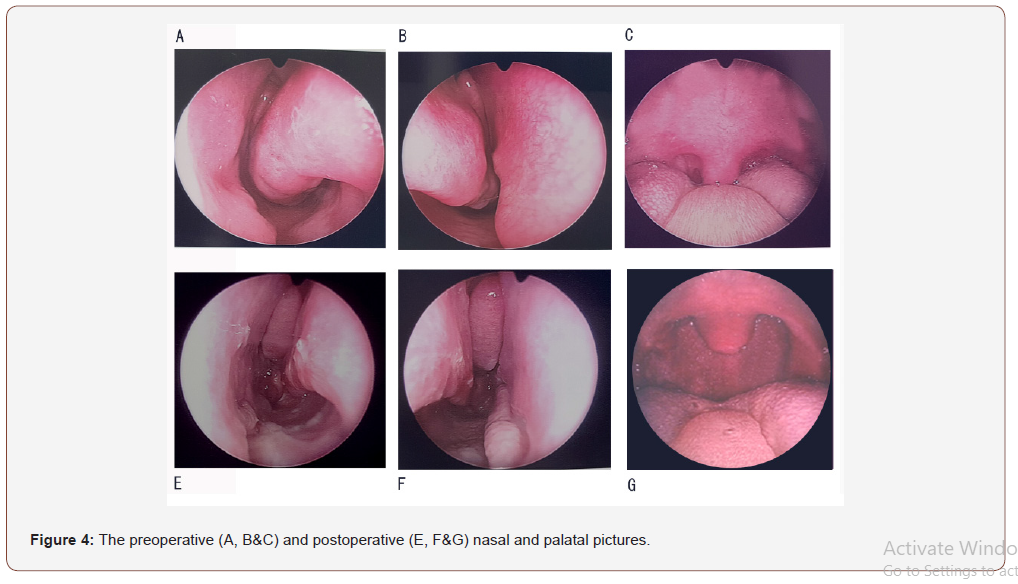

Now the free edge of the newly formed soft palate is covered by normal palatal mucosa. Using unidirectional type, the upper part of the laterally placed posterior pillar flap is sutured to the most superolateral part of the anterior pillar passing around the pterygomandibular raphe where can be located by digital palpation, creating a good tension in the lateral pharyngeal wall and rest of the posterior pillar is sutured directly to the anterior pillar through its whole length. Lastly, the uvula is shortened [Figure 3D, E&F]. After surgery, all patients were admitted to a room close to the nurse’s station, with continuous pulse oximetry monitoring (Figure 4).

Criteria of Surgical Success

Surgical success was defined as a reduction of at least 50% in preoperative AHI and a postoperative AHI of less than 20 per hour [23].

Postoperative Complications

Postoperative complications, including dry mouth, nasal regurgitation, excessive postnasal drip, taste disturbance, tonsil bleeding, epistaxis, and respiratory compromise, were assessed for all patients.

Results

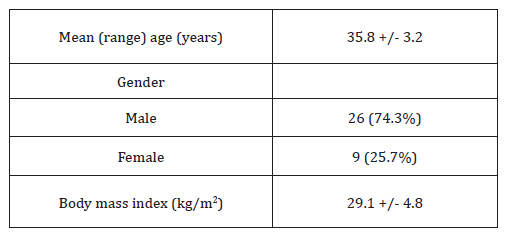

From April 2015 and January 2019, 35 patients were treated with this technique. Table 1 shows the demographic data of the patients.

Table 1: Demographic data of the patients.

Subjective symptoms

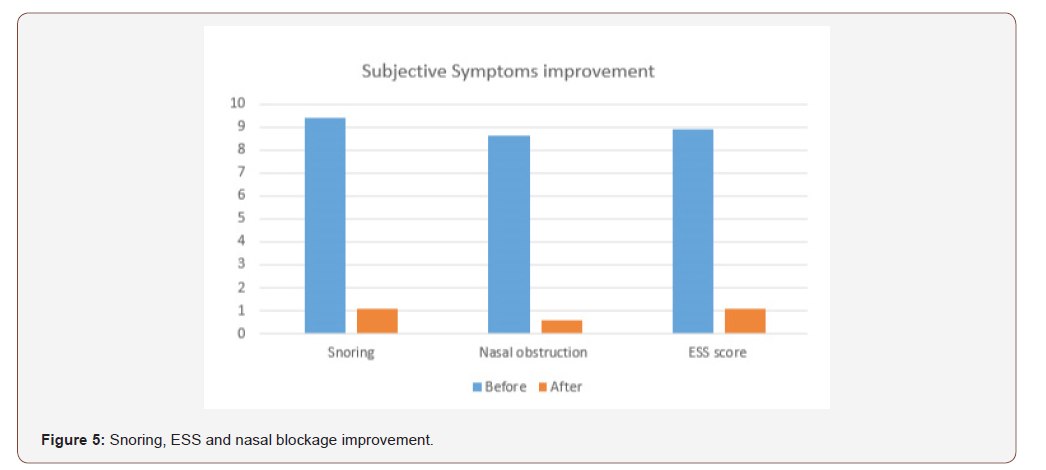

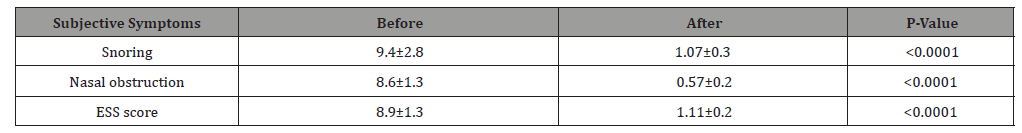

The changes in subjective symptoms before and after single stage modified barbed soft palatal posterior pillar flap palato pharyngoplasty and nasal surgery are displayed in (Table 2 & Figure 5).

Table 2: Subjective Symptoms before and after Single-Staged modified barbed soft palatal posterior pillar flap palate pharyngoplasty and nasal surgery (n = 35).

OSA improvement

The changes in polysomnographic parameters before and after single stage modified barbed soft palatal posterior pillar flap palato pharyngoplasty and nasal surgery are displayed in (Table 3 & Figure 6).

DISE analysis

An overview of the distribution of the levels of upper airway collapse for all patients included in this study based on DISE scoring is provided in (Table 4).

Surgical success

There was no statistically significant difference between preoperative and postoperative BMI (from 29.1± 4.8 kg/m2 to 25.1±2.6 kg/m2). The overall surgical success rate for all 35 patients included in this study using Sher’s criteria was 89% (31/35).

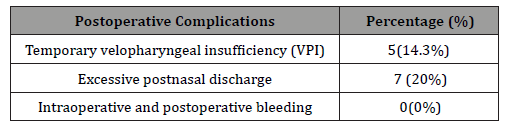

Intra-operative and post-operative complications

There were no serious or major complications during or after surgery, including respiratory compromise. All postoperative complications were relatively minor. Temporary velopharyngeal insufficiency (VPI) improved within 3 weeks of surgery. The excessive post-nasal discharge was due to the shortening of the uvula. In all cases, this condition started to improve within 1-2 months of surgery. No serious intraoperative or immediate postoperative complications were reported (Table 5).

Table 3: Polysomnographic Parameters before and after Single-Staged modified barbed soft palatal posterior pillar flap palate pharyngoplasty and nasal surgery (n = 35).

Table 4: Overview of DISE scoring (n = 35).

Table 5: Intra-operative and post-operative Complications.

Patients’ satisfaction

All patients were satisfied with the single-stage treatment, tolerated well with the overnight nasal packing with no evidence of postoperative airway obstruction. Cost-effectiveness in terms of total hospitalization was subjectively ideal in comparison to hospitalization for staged operation when the patients were considering the same scenario for two admissions.

Discussion

Most reports in the literature focus on the efficacy of a single procedure for OSA. Since OSA is usually caused by multilevel obstructions, the true focus on efficacy should be on multilevel surgical intervention [9]. As a consequence of the multi-factorial etiology of OSA, surgical therapies need to be tailored for each patient, as there is no perfect surgery that will fit all patients and so effective surgical management of OSA depends upon determining different levels of obstruction. DISE is one of the best tools for the determination of the site of obstruction that helps to tailor the operative procedures according to the anatomical sites of obstruction [14,15].

In this study, DISE was the main indicator to have the decision for palatal collapse, lateral pharyngeal wall collapse surgeries together with tonsillectomy. In all patients, the sequence of events was as follows: after completion of DISE, induction of general anesthesia with oral endotracheal intubation followed by nasal surgery and lastly the modified barbed palato pharyngoplasty was carried out. In this study, nasal surgery aimed to get relief from nasal blockage, to eliminate snoring and also getting the maximum benefit of improvement in OSA. In this study Nasal blockage was improved with nasal Obstruction Visual Analog Scale from 8.6±1.3 to 0.57±0.2 (p<0.0001).

The role of nasal surgery in treating patients with snoring and OSA has been investigated. Ishii L et al in their meta-analysis study, to determine the role of isolated nasal surgery in patients with obstructive sleep apnea, concluded that isolated nasal surgery for patients with nasal obstruction and obstructive sleep apnea improved some sleep parameters, as shown by significant improvements in ESS and RDI, but had no significant improvements on AHI and future controlled studies with larger groups are needed to confirm the benefits of isolated nasal surgery in this patient population [24]. Jun W et al in their study meta-analysis concluded that Both AHI and ESS improved significantly after isolated nasal surgery, but the improvement of AHI is slightly significant and Future randomized controlled trials are needed to confirm the long-term benefits of nasal surgery on OSA [25]. Li HY, et al [7], concluded that the Correction of an obstructed nasal airway significantly improves disease specific and quality of life in adult patients with obstructive sleep apnea who also have nasal obstruction symptoms.

When the nasal obstruction is identified in cases of OSA with suspected oropharyngeal and nasal obstruction, oropharyngeal surgery can be carried out in combination with nasal surgery in either a single-staged or multi staged manner. However, it remains unclear whether oropharyngeal and nasal surgery should be performed simultaneously or separately because little published information exists regarding this issue [26]. In this study, the overall surgical success rate for all 35 patients using Sher’s criteria was 89% (31/35). AHI was improved from 38.4±23.3 to 12.3±21.1. All subjective symptoms were improved. Nasal obstruction Visual Analog Scale was improved from 8.6±1.3 to 0.57±0.2. snoring visual analog scale was improved from 9.4±2.8 to 1.07±0.3. ESS score was improved from 8.9±1.3 to 1.11±0.2.

Li et al in 2005 in their retrospective study, that compared the outcomes of two types of combined nasal-palatopharyngeal surgery (simultaneous and staged) for the treatment of OSA, found that collected data indicate that surgical outcomes in a simultaneous surgery group were equivalent to those in a staged surgery group. This result considered to be coinciding with our results regarding surgical outcomes. In this study, there were a few minor complications after surgery that were temporary and resolved without Sequelae. No intraoperative or postoperative complications were observed. No recorded cases of immediate postoperative respiratory compromise or cardiovascular complications. These results are consistent with the results of previous studies showing that simultaneous surgeries do not carry additional risk [16,17,26].

Busaba [16] investigated whether same-stage nasalpalatopharyngeal surgery for OSAS with nasal obstruction is relatively safe in selected patients when significant comorbid diseases are not present and retrospectively compared postoperative complications between same-stage nasalpalatopharyngeal and staged-surgery groups and concluded that same-stage nasal palatopharyngeal surgery is safe for OSAS patients with nasal obstruction. Choi et al in their study, in 2011, concluded that single staged modified UPPP with nasal surgery is an available and relatively safe surgical approach in OSA patients with nasal obstruction. Li HY, et al [17] in their retrospective study found that simultaneous nasal–palatopharyngeal surgery is as effective and as satisfactory as staged surgery However, combined nasal–oropharyngeal surgery has a few disadvantages. One of the major disadvantages is the risk of severe complications such as respiratory compromise and cardiovascular complications. Hsu pp [27] had the impression that performing staged procedures is a safer option in the surgical management of patients with moderate to severe OSA, as nasal packing with blood clot after nasal surgery will further compromise the narrow, obstructed upper airway of patients with moderate to severe OSA if nasal surgery is performed first or concurrently.

In this study, Cost-effectiveness in terms of total hospitalization was subjectively ideal for all patients.

Li et al in 2005 in their retrospective study concluded that single-stage multilevel surgery can lower the total hospitalization expenses when compared to multi-staged surgery.

This study was conducted to determine the clinical efficacy of single stage modified barbed soft palatal posterior pillar flap palatopharyngoplasty with nasal surgery for OSA with nasal obstruction. Same-stage nasal and palatopharyngeal surgery for OSAS is safe with good patient’s satisfaction. Patients could be monitored with continuous pulse oximetry and managed outside of an intensive care unit.

Limitations

In this study, the main objective was to assess the safety of simultaneous surgery (nasal-palatopharyngeal) and we’ve shown no major complications, we did not focus on the postoperative pain as I was discussed in the previous study for pharyngeal surgery alone [12]. It is sure will be more painful because the patients cannot breathe properly through the nose during the postoperative period, I think this would be a good subject for the next controlled study: one arm staged and one simultaneous surgery. In this current single-stage multilevel surgery we were not able to be compared the total hospitalization expenses to other multi-staged surgery as this needs a separate study. Although symptoms were effectively alleviated with surgery; and although no serious complications were observed, information about the potential long-term subjective outcomes cannot be provided to patients when considering such surgery.

Conclusion

Single-staged versus multi-staged treatment remains an area of controversy. The major concern about single-stage multilevel surgery for OSA involves its safety. Proponents of each approach have valid evidence that either approach is reasonably safe. Appropriate patient selection is very important in achieving the best results.

Acknowledgement

None

Conflict of Interest

No conflict of interest.

References

- Kotecha B (2011) The nose, snoring and obstructive sleep apnea. Rhinology 49(3): 259-263.

- Morris LG, Burschtin O, Lebowitz RA, Jacobs JB, Lee KC, et al. (2005) Nasal obstruction and sleep-disordered breathing: a study using acoustic rhinometry. Am J Rhinol 19: 33-39.

- Verse T, Pirsig W (2003) Impact of impaired nasal breathing on sleep-disordered breathing. Sleep Breath 7: 63-76.

- Kohler M, Bloch KE, Stradling JR (2007) The role of the nose in the pathogenesis of obstructive sleep apnoea and snoring. Eur Respir J 30(6): 1208-1215.

- Bican A, Kahraman A, Bora I, Kahveci R, Hakyemez B (2010) What is the efficacy of nasal surgery in patients with obstructive sleep apnea syndrome? J Craniofac Surg 21(6):1801-1806.

- Kim ST, Choi JH, Jeon HG, Cha HE, Kim DY, et al. (2004) Polysomnographic effects of nasal surgery for snoring and obstructive sleep apnea. Acta Otolaryngol 124(3): 297-300.

- Li HY, Lin Y, Chen NH, Lee LA, Fang TJ, et al. (2008) Improvement in quality of life after nasal surgery alone for patients with obstructive sleep apnea and nasal obstruction. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 134(4): 429-433.

- Poirier J, George C, Rotenberg B (2014) The effect of nasal surgery on nasal continuous positive airway pressure compliance. Laryngoscope 124(1): 317-319

- Lin HC, Friedman M, Chang HW, Gurpinar B (2008) The efficacy of multilevel surgery of the upper airway in adults with obstructive sleep apnea/hypopnea syndrome. Laryngoscope 118: 902-908.

- Pang KP, Woodson BT (2007) Expansion sphincter pharyngoplasty: a new technique for the treatment of obstructive sleep apnea. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 137: 110-114.

- Elbassiouny AM (2014) Soft palatal webbing flap palate pharyngoplasty for both soft palatal and oropharyngeal lateral wall collapse in the treatment of snoring and obstructive sleep apnea: a new innovative technique without tonsillectomy. Sleep Breath 19(2): 481-487.

- Elbassiouny AM (2016) Modified barbed soft palatal posterior pillar webbing flap palate pharyngoplasty. Sleep Breath 20(2): 829-836.

- Lan MC, Liu SY, Lan MY, Modi R, Capasso R (2015) Lateral pharyngeal wall collapse associated with hypoxemia in obstructive sleep apnea. Laryngoscope 125(10): 2408-2412.

- Vanderveken OM, Vroegop AVM, Van de Heyning PH, Braem MJ (2011) Drug-induced sleep endoscopy completed with a simulation bite approach for the prediction of the outcome of treatment of obstructive sleep apnea with mandibular repositioning appliances. Operative Techniques in Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery 22(2): 175-182.

- Kezirian EJ, Hohenhorst W, De Vries N (2011) Drug-induced sleep endoscopy: The VOTE classification. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol 268: 1233-1236.

- Busaba NY (2002) Same-stage nasal and palatopharyngeal surgery for obstructive sleep apnea: is it safe? Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 126: 399-403.

- Li HY, Wang PC, Hsu CY, Lee SW, Chen NH, et al. (2005) Combined nasal-palatopharyngeal surgery for obstructive sleep apnea: simultaneous or staged? Acta Otolaryngol 125: 298-303.

- Ciprandi G, Mora F, Cassano M, Gallina AM, Mora R (2009) Visual analog scale (VAS) and nasal obstruction in persistent allergic rhinitis. Otolaryngol Head and Neck Surg 141(4): 527-529.

- Friedman M, Ibrahim H, Bass L (2002) Clinical staging for sleep-disordered breathing. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 127: 13-21.

- Kotani Y, Shimazawa M, Yoshimura S, Iwama T, Hara H, et al. (2008) The experimental and clinical pharmacology of propofol, an anesthetic agent with neuroprotective properties. CNS Neurosci Ther 14: 95-106.

- Eastwood PR, Platt PR, Shepherd K, Maddison K, Hillman DR, et al. (2005) Collapsibility of the upper airway at different concentrations of propofol anesthesia. Anesthesiology 103: 470-477.

- Iber C, Ancoli Israeli S, Chesson AL, Quan SF (2007) The AASM Manual for the Scoring of Sleep and Associated Events: Rules, Terminology, and Technical Specifications, Westchester, IL, American Academy of Sleep Medicine.

- Bettina Carvalho, Jennifer Hsia, Robson Capasso (2012) Surgical Therapy of Obstructive Sleep Apnea: A Review. Neurotherapeutics 9(4): 710-716.

- Ishii L, Roxbury C, Godoy A, Ishman S, Ishii M, et al. (2015) Does nasal surgery improve OSA in patients with nasal obstruction and OSA? A meta-analysis. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 153: 326-333.

- Wu J, Zhao G, Li Y, Zang H, Wang T, et al. (2017) Apnea hypopnea index decreased significantly after nasal surgery for obstructive sleep apnea: A meta-analysis. Medicine (Baltimore) 96(5): e6008

- Choi JH, Kim EJ, Cho WS, Kim YS, Choi J, et al (2011) Efficacy of single stage modified uvulopalatepharyngoplasty with nasal surgery in adults with obstructive sleep apnea syndrome. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 144(6): 994-999.

- Hsu pp, Brett RH (2001) Multiple Level Pharyngeal Surgery for Obstructive Sleep Apnoea. Singapore Med J 42(4): 160-164.

-

Ahmed M M E D E. Single-Stage Drug-Induced Sleep Endoscopy, Nasal Surgery and Modified Barbed Soft Palatal Posterior Pillar Flap Palato Pharyngoplasty for Treatment of Obstructive Sleep Apnea. On J Otolaryngol & Rhinol. 2(2): 2020. OJOR.MS.ID.000532.

-

Palatopharyngeal surgery, Nasal surgery, Sleep apnea, Oropharyngeal, Sleep endoscopy, Nasal Obstruction, hypopharynx, retroglossal area, Rhino nasal, Tonsil bleeding.

-

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.

- Abstract

- Introduction

- Materials and Methods

- Subjective Symptoms

- Upper Airway Examination

- Drug-Induced Sleep Endoscopy (DISE)

- Polysomnography

- Statistical Analysis

- Surgical Procedure

- Criteria of Surgical Success

- Postoperative Complications

- Results

- Discussion

- Limitations

- Conclusion

- Acknowledgement

- Conflict of Interest

- References