Mini Review

Mini Review

Proton Pump Inhibitors for Laryngopharyngeal Reflux: What Do We Know?

Christine M Carmichael*

Woolfolk School of Communication Sciences and Disorders, Our Lady of the Lake University, United States

Christine M Carmichael, Woolfolk School of Communication Sciences and Disorders, Our Lady of the Lake University, United States.

Received Date: December 17, 2019; Published Date: December 19, 2019

Abstract

Proton pump inhibitors have been used for the last three decades to treat reflux and other gastric disorders. Although originally FDA approved and presumed safe, reports of serious health conditions linked to long-term use are surfacing. The FDA has since issued several announcements regarding safety of proton pump inhibitors. Specific health risks are reviewed, and alternative treatments presented.

Keywords: Laryngopharyngeal reflux; Proton pump inhibitor; Safety

Abbreviations: PPI: Proton pump inhibitor; FDA: Food and drug administration; OTC: Over the counter; GERD: Gastroesophageal reflux disease; LPR: Laryngopharyngeal reflux; BID: Bis in die [twice a day]; ANC: Antacid neutralizing capacity; PRN: Pro re nata [as needed]

Introduction

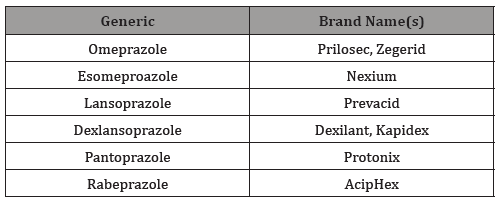

The first proton pump inhibitor (PPI) came on the market thirty years ago. As of 2019, there are 6 commercially available generic PPIs approved by the United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA) [1] under several brand names (Table 1). PPIs work to reduce the amount of gastric acid in the stomach and prevent the movement of acid into the esophagus. Specifically, PPIs inhibit the action of the proton pump which is the last process of creating and excreting stomach acid [2]. They are effective in blocking acid secretion by up to 99 percent and offer up to 76% symptom relief [3].

Table 1: Proton Pump Inhibitors in the United States.

Scope of the Problem

PPIs became one of the most widely prescribed, even overprescribed, as well as overused over the counter (OTC) treatments for gastroesophageal disease (GERD), laryngopharyngeal reflux (LPR) and other gastrointestinal disorders due to their effectiveness to suppress gastric acid [2]. OTC PPIs are marketed at lower doses than prescription strength, and per directions for usage, are only intended for 14-day use up to 3 times per year. Although short-term use is considered to be somewhat safe, several safety concerns have arisen linking long-term use of PPIs to a variety of serious health problems. While randomized clinical trials are lacking, research findings including observational studies suggest long-term PPI use is associated with risk of vitamin B-12 deficiency, calcium, iron and magnesium malabsorption [4-7], myocardial infarction [8,9], osteoporosis and bone fractures of the hip, wrist and spine [5, 10-12], kidney disease [13-16], dementia [17-20], infections including Clostridium difficile, Salmonella and pneumonia [21-23] and neoplasm and gastric cancer [24-26], with some of these conditions reportedly impacting premature death [27,28]. Studies have shown increased risks not only with extended use but with increased dosage, which could prove detrimental in the case of LPR in which BID use of PPIs is recommended. Moreover, the FDA has released several consumer updates, press releases and other drug safety communications in 2010, 2011 and 2012 implicating long-term use with health risks, prompting label PPIs became one of the most widely prescribed, even overprescribed, as well as overused over the counter (OTC) treatments for gastroesophageal disease (GERD), laryngopharyngeal reflux (LPR) and other gastrointestinal disorders due to their effectiveness to suppress gastric acid [2]. OTC PPIs are marketed at lower doses than prescription strength, and per directions for usage, are only intended for 14-day use up to 3 times per year. Although short-term use is considered to be somewhat safe, several safety concerns have arisen linking long-term use of PPIs to a variety of serious health problems. While randomized clinical trials are lacking, research findings including observational studies suggest long-term PPI use is associated with risk of vitamin B-12 deficiency, calcium, iron and magnesium malabsorption [4-7], myocardial infarction [8,9], osteoporosis and bone fractures of the hip, wrist and spine [5, 10-12], kidney disease [13-16], dementia [17-20], infections including Clostridium difficile, Salmonella and pneumonia [21-23] and neoplasm and gastric cancer [24-26], with some of these conditions reportedly impacting premature death [27,28]. Studies have shown increased risks not only with extended use but with increased dosage, which could prove detrimental in the case of LPR in which BID use of PPIs is recommended. Moreover, the FDA has released several consumer updates, press releases and other drug safety communications in 2010, 2011 and 2012 implicating long-term use with health risks, prompting label

Final Considerations

PPIs are known to cause serious health conditions and even death especially when taken long-term. Although the recommended treatment regimen for PPIs is 3-6 months or shorter for LPR, many end up continuing the drugs for years, prompting consideration for short-term or alternative treatment. Alternative medical management for treating LPR include H2-receptor antagonists (H2 blockers) or antacids; however, H2 blockers have also been linked to some of the same health risks as PPIs [8, 16, 17, 21, 22, 27]. Like PPIs, H2 blockers are prescribed and available OTC, and also work to suppress stomach acid production; hence, may cause similar conditions. Although investigations into PPIs and H2 blockers are ongoing, the FDA issued a recent statement in September 2019 alerting patients and health care professionals of N-nitroso dimethylamine, a probable human carcinogen, found in ranitidine products, including the brand name Zantac.

Antacids are a class of drugs available OTC that offer on demand system relief by neutralizing gastric acidity and inhibiting pepsin when taken within an hour after a meal [29]. There are differences between formulations and brands of commercially available antacids, but the most effective have high antacid neutralizing capacity (ANC), work rapidly, and have a long duration of neutralization. The FDA requires that antacids sold in the United States have a minimum ANC of 5 milliequivalents [of acid that is neutralized] per dose. While antacids are intended for PRN use and present few minor side effects, extensive use and heavy dosing of certain formulas has been reported to cause osteomalacia, milkalkali syndrome, and hypophosphatemia [29]. As with any drug, there are warnings, precautions and drug interactions for select populations, depending on the type of antacid.

Reflux behavioral management is a beneficial adjunct to drug therapy and may be a successful nonpharmacological alternative as a solo treatment for mild to moderate LPR. Behavioral guidelines involve lifestyle strategies of dietary modifications, smoking cessation, weight management and elevating the head of the bed to avoid nocturnal reflux [30]. Dietary changes include avoidance of highly acidic or fatty foods, caffeine, alcohol, soda, binge eating, eating too close to exercising, and eating too close to bedtime.

Acknowledgement

None.

Conflict of Interest

No conflict of interest

References

- US Food and Drug Administration. Proton pump inhibitors.

- Strand DS, Kim D, Peura DA (2017) 25 years of proton pump inhibitors: A comprehensive review. Gut and Liver 11(1): 27-37.

- Scarpignato C (2012) Poor effectiveness of proton pump inhibitors in non-erosive reflux disease: The truth in the end! Neurogastroenterol Motil 24(8): 697-704.

- Epstein M, McGrath S, Law F (2006) Proton-pump inhibitors and hypomagnesemic hypoparathyroidism. N Egl J Med 355(17): 1834-1836.

- Cheungpasitporn W, Thongprayoon C, Kittanamongkolchai W, Srivali N, Edmonds PJ, et al. (2015) Proton pump inhibitors linked to hypomagnesemia: A systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. Ren Fail 37(7): 1237-1241.

- Lam JR, Schneider JL, Zhao W, Corley DA (2013) Proton pump inhibitor and histamine 2 receptor antagonist use and vitamin B12 deficiency. JAMA 310(22): 2435-2442.

- William JH, Danziger J (2016) Proton-pump inhibitor-induced hypomagnesemia: Current research and proposed mechanisms. World J Nephrol 5: 152-157.

- Arbel Y, Birati EY, Finkelstein A, Halkin A, Kletzel H, et al. (2013) Platelet inhibitory effect of Clopidogrel in patients treated with omeprazole, pantoprazole, and famitodine: A prospective, randomized, crossover study. Clin Cardiol 36(6): 342-346.

- Shah NH, Le Pendu P, Bauer-Mehren A, Ghebremariam YT, Srinivasan VI, et al. (2015). Proton Pump Inhibitor Usage and the Risk of Myocardial Infarction in the General Population.

- Zhou B, Huang Y, Li H, Sun W, Liu J (2016) Proton-pump inhibitors and risk of fractures: An update meta-analysis. Osteoporos Int 27(1): 339-347.

- Anderson BN, Johansen PB, Abrahamsen B (2016) Proton pump inhibitors and osteoporosis. Curr Opin Rheumatol 28: 420-425.

- Munson JC, Bynum JP, Bell JE, Cantu R, McDonough C, et al. (2016) Patterns of prescription drug use before and after fragility fracture. JAMA Intern Med 176: 1531-1538.

- Lazarus B, Chen Y, Wilson FP, Sang Y, Chang AR, et al. (2016) Proton pump inhibitor use and the risk of chronic kidney disease. JAMA Intern Med 176(2): 238-246.

- Xie Y, Bowe B, Li T, Xian H, Balasubramanian S, et al. (2016) Proton pump inhibitors and the risk of incident CKD and progression to ESRD. J Am Soc Nephrol 27(10): 3153-3163.

- Klatte DCF, Gasparini A, Xu H, De Deco P, Trevisan M, et al. (2017) Association between proton pump inhibitor use and risk of progression of chronic kidney disease. Gastroenterology 153(3): 702-710.

- Wijarnpreecha K, Thongprayoon C, Chesdachai S, Panjawatanana P, et al. (2017) Associations of proton-pump inhibitors and H2 receptor antagonists with chronic kidney disease: A meta-analysis. Dig Dis Sci 62: 2821-2827.

- Gomm W, Von Holt K, Thome F, Broich K, Maier W, et al. (2016) Association of proton pump inhibitors with risk of dementia: A pharmacoepidemiological claims data analysis. JAMA Neurol 73: 410-416.

- Tai SY, Chien CY, Wu DC, Lin KD, Ho BL, et al. (2017) Risk of dementia from proton pump inhibitor use in Asian population: A nationwide cohort study in Taiwan. PLoS ONE 12: e0171006.

- Haenisch B, Von Holt K, Wiese B, Prokein J, Lange C, et al. (2015) Risk of dementia in elderly patients with the use of proton pump inhibitors. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci 265(5): 419-428.

- Kuller LH (2016) Do proton pump inhibitors increase the risk of dementia? JAMA Neurol 73: 379-381.

- Freedberg DE, Toussaint NC, Chen SP, Ratner AJ, Whittier S, et al. (2015) Proton pump inhibitors alter specific taxa in the human microbiome: A crossover trial. Gastroenterology 149(4): 883-885.e9.

- Tariq P, Singh S, Gupta A, Pardi DS, Khanna S (2017) Association of gastric acid suppression with recurrent Clostridium difficile infection: A systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Intern Med 177(6): 784-791.

- Lambert AA, Lam JO, Paik JJ, Ugarte Gil C, Drummond MB, et al. (2015) Risk of community-acquired pneumonia with outpatient proton pump inhibitor therapy: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One 10(6): e0128004.

- Cheung KS, Laung WK (2019) Long-term use of proton-pump inhibitors and risk of gastric cancer: A review of the current evidence. Therap Adv Gastroenterol 12: 1-11.

- Cheung KS, Chan EW, Wong AYS, Chen L, Wong ICK, et al. (2018) Long-term proton pump inhibitors and risk of gastric cancer development after treatment for Helicobacter pylori: a population-based study. Gut 67: 28-35.

- Waldum HL, Fossmark R (2017) Proton pump inhibitors and gastric cancer: A long expected side effect finally reported also in man. Gut 67: 199-200.

- Xie Y, Bowe B, Li T, Xian H, Yan Y, et al. (2017) Risk of death among users of proton pump inhibitors: A longitudinal observational cohort study of United States veterans. BMJ Open 7(6): e015735.

- Xie Y, Bowe B, Yan Y, Xian H, Li T, et al. (2019) Estimates of all-cause mortality and cause specific mortality associated with proton pump inhibitors among US veterans: Cohort study. BMJ 365: l1580.

- Washington N (1991) Antacids and Anti-reflux Agents. CRC Press, Boca Raton, FL, United States.

- Sethi S, Richter JE (2017) Diet and gastroesophageal reflux disease: Role in pathogenesis and management. Curr Opin Gastroenterol 33(2): 107-111.

-

Christine M Carmichael. Proton Pump Inhibitors for Laryngopharyngeal Reflux: What Do We Know?. On J Otolaryngol & Rhinol. 2(1): 2019. OJOR.MS.ID.000528.

-

Laryngopharyngeal reflux, Gastroesophageal disease, Pneumonia, Hypophosphatemia, Drug therapy, Nocturnal reflux, Human carcinogen, Nitroso dimethylamine, Gastric disorders.

-

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.