Research Article

Research Article

Longitudinal Analysis of Calcium and Parathyroid Hormone Levels in Normocalcemic Patients Following Total Thyroidectomy

Abdulrahman Faeq Alzamil1*, Abdullah Omar Aljafaari2, Kawther Nermish3, Fahad Khalifa Bedawi4, Sara Sabra5, Dalal Alromaihi6, Naji Alamuddin7 and Omar Sabra8

1Saudi Board ORL-HNS, Bahrain Royal Medical Services, King Hamad University Hospital, Bachelor of Medicine, Bachelor of Surgery, MBBS, Bahrain

2King Hamad University Hospital, King Fahad University Hospital, Medical Doctor, Medical Doctor, MD, Bahrain

3Royal College of Surgeon in Irland, Bahrain

4Intercollegiate MRCS examination and intercollegiate Diploma in Otolaryngology - Head and neck Surgery MRCS (DO-HNS), Fellow of The European Board of Otorhinolaryngology, Head and Neck Surgery (EBEORL-HNS), Bachelor of Science, Bsc, Medical Doctor, MD, Bahrain

5Royal College of Surgeons in Ireland, Bahrain

6Royal College of Surgeons in Ireland, Bahrain, King Hamad University Hospital, Master of Science, Msc, Medical Doctor, MD, Bahrain

7Awali Hospital, Royal College of Surgeons in Ireland, Bahrain, Master of Science, Msc, Medical Doctor, MD, Bahrain

8Royal College of Surgeons in Ireland, Bahrain, King Hamad University Hospital, Medical Doctor, MD, Bahrain

Abdulrahman Faeq Alzamil, Saudi Board ORL-HNS, Bahrain Royal Medical Services, King Hamad University Hospital, Bachelor of Medicine, Bachelor of Surgery, MBBS, Bahrain.

Received Date: November 14, 2024; Published Date: November 26, 2024

Abstract

Purpose: To investigate the relationship between pre- and post-operative calcium and parathyroid hormone (PTH) levels in normocalcemic patients undergoing total thyroidectomy.

Methods: We included all adult patients who are undergoing complete thyroidectomy, collecting data on serum calcium, PTH, vitamin D, and thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) levels before the operation as well as six months after the operation. We excluded those patients with significant changes in vitamin D or on supplementation. Statistical analysis used paired T-tests to measure alterations in biochemical indicators.

Results: Out of 23 patients included, it was seen that although corrected calcium and PTH levels decreased significantly, everyone stayed within the normocalcemic range six months after thyroidectomy. There were no notable changes in vitamin D and TSH levels. This implies an impact of total thyroidectomy on parathyroid gland function.

Conclusion: This study shows a noticeable drop in calcium and PTH levels after thyroidectomy. Although these changes are not enough to reach clinical manifestations, it is considered of statistical significance. These findings indicate the need for individualized management and close monitoring to avoid long-term complications. More investigation should concentrate on the probable significance of these biochemistry alterations within clinical settings, along with creating methods for intervening accurately.

Introduction

Thyroidectomy is generally considered safe and has evolved over the years to the point where hospital stays are often very short, or even unnecessary. Proper patient education is essential to prepare for potential complications like hypocalcemia levels and hypoparathyroidism resulting primarily from accidental injury or removal of the parathyroid glands [1-3, 6]. Hypoparathyroidism is defined as a drop in parathyroid hormone (PTH) level to below normal values which occurs after surgery either transiently (might go up to 6 months) or permanently [4-5]. Although damage to the parathyroid glands can result in a diminished release of parathyroid hormone (PTH), leading to a decrease in its level, it may not be sufficient to be classified as hypoparathyroidism. Patients can experience symptoms associated with low calcium levels without officially fulfilling the diagnostic criteria for hypoparathyroidism. This condition has been recognized as parathyroid insufficiency [6]. This subset of patients demonstrates that even modest decreases in PTH levels can induce symptoms before reaching below normal levels. Such observations underscore the importance of assessing individual PTH changes rather than relying solely on established reference ranges. The concept of a “normal reference range” is statistically derived from population data and may not apply to every individual. In some cases, maintaining calcium homeostasis may require much narrower PTH ranges than those considered normal for the broader population.

Previous studies showed that an early drop in calcium or PTH levels predict the later development of permanent hypoparathyroidism [7], even when this early drop is still within the normal range. A drop in PTH level by itself without reaching abnormally low levels might predict a long-term shift in function. The study aims to document a long-term shift in calcium and PTH levels individually for a group of total thyroidectomy patients, by comparing each patient’s post-operative levels to his preoperative ones.

Vitamin D is another major controller of calcium and PTH level. Although calcium and PTH do not look to influence circulating vitamin D level [8, 9]. Vitamin D level is mainly related to dietary intake and supplements. As such a major change of vitamin D during the study timeframe should be considered as a source of bias and should be restricted to reduce confounding bias [10].

Materials and Methods

All adult patients undergoing total thyroidectomy between Jun 2021 and January 2023, operated by the primary head and neck surgeon at a tertiary care university hospital in Bahrain, King Hamad University Hospital were included in the study. Data were collected prospectively. Collected data included the patient’s age and sex, date of surgery, and patient’s diagnosis. Blood was collected on all patients for a TSH and a full calcium profile which included total calcium, phosphorus, albumin, PTH, and vitamin D levels. The same blood tests were repeated 6 months after surgery. Calcium was measured in millimoles per liter (mmol/L), vitamin D in nanograms per milliliter (ng/mL), albumin in grams per liter (g/L), TSH in microunits per milliliter (U/mL), and PTH in picograms per milliliter (pg/mL). Corrected calcium level was calculated based on available calcium and albumin levels. All tests were measured in the same blood sample to avoid errors related to overtime fluctuation in calcium, PTH, and albumin levels. Patients with permanent hypoparathyroidism, detected at 6 months, manifested by a PTH level lower than 10pg/ml were excluded. Patients who were noticed to have a shift in vitamin D level of more than 10ng/ ml within the timeframe of the study were considered a source of bias, as such a shift would influence PTH, and calcium levels and these patients were excluded [10]. Data was restricted to patients with a stable vitamin D level over the time frame of the study. We defined a “stable vitamin D level” as any variation that is less than or equal to 10 units within the timeframe of the study. This range was chosen arbitrarily as no reference in literature is available to define “stable vitamin D level”.

Data Analysis

Collected data was entered and organized in an Excel sheet and then analyzed by using Excel and SPSS software version 20. The variables that have been collected include continuous values which were presented as mean and standard deviation. Unilateral paired T-test was used to spot a significant decrease in PTH and calcium levels post-operatively (6 months post-op) compared to that pre-operatively (H0: value 2=value 1 vs H1: value2 ≤ value 1). Test was considered significant if the p-value was <0.05. After excluding patients with more than 10 units of Vitamin D fluctuation, preoperative and post-operative vitamin D levels were compared using paired T-test to rule out any significant difference between the 2 sets of measures H0: value2=value1 vs H1: value 2 ≠value 1). Other values analyzed included TSH level fluctuation. Post hoc power was used to assess the reliability of the observed results on our sample size. A result of ≥0.8 implies that significant test results are reliable.

Ethical considerations

The study was approved by the research institutional review board at King Hamad University Hospital, Bahrain. Participants’ identities were kept anonymous, and data was retrieved using the hospital health information system.

Results

Between June 2021 and January 2023, 45 patients underwent total thyroidectomy without any form of concomitant neck dissection. Patients with previous thyroid surgery or with associated neck dissection were not included. Eleven patients failed to follow and were excluded. Another 11 patients showed a shift in vitamin d level of more than 10 units or were noted to be on vitamin D or calcium replacement throughout the study and consequently were excluded. The study included 23 patients with complete data. All included subjects were defined as normocalcemic and having normal PTH levels as per the normal range and stable vitamin D levels.

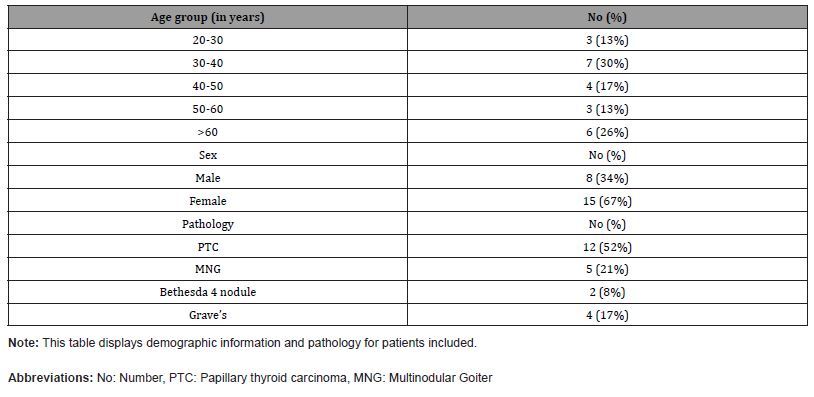

Within the sample, the indication for surgical intervention was attributable to papillary thyroid carcinoma (PTC), in 53.8% of the cases, followed by multinodular goiter (MNG), which constituted 29.6% of the cases. The demographic data showed female predominance, representing 70% of the sample, with the most represented age category being individuals older than 50 years, comprising 48% of the cohort. Comprehensive demographic information, including age, gender, and pathological diagnoses, are delineated in Table 1.

Table 1:Demographic information and pathology.

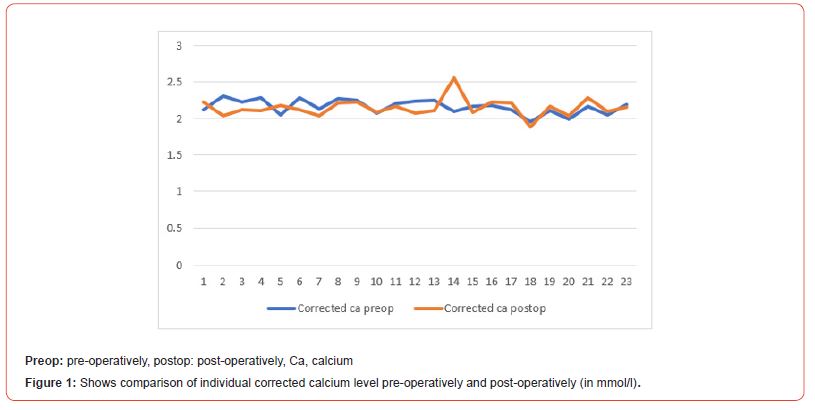

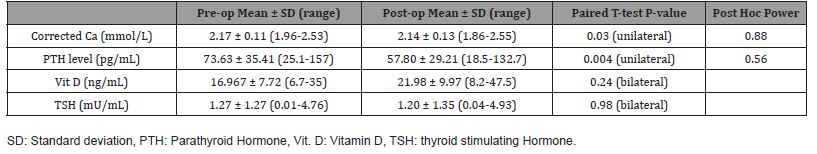

The mean value for corrected calcium pre-surgical level was 2.17 mmol/L while the mean post-surgical level was 2.14 mmol/L. A significance was seen in one-tailed t-test when comparing corrected calcium levels post-surgery to levels prior to surgery (p=0.013) indicating a statistically significant drop. See Figure 1.

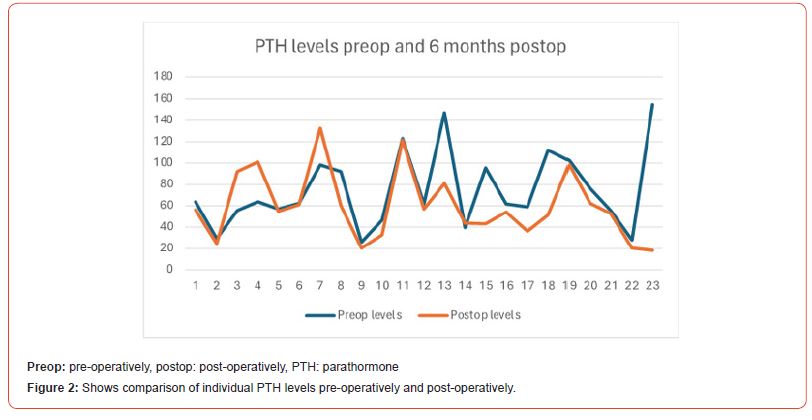

On the other hand, the mean value for parathyroid hormone levels pre-operatively was 73.63 pg/mL compared to 57.80 pg/mL post-operatively. One-tailed t-test has also shown a significant drop when comparing PTH levels before and after surgery (p=0.03). See Figure 2.

When vitamin D was compared between the 2 settings using paired T-test, there was a non-significant change in tested levels (p=0.24). When TSH was compared between the 2 settings, there was no significant change in blood levels (p=0.98).

The calculated post hoc power value was low for PTH (0.56), but high (0.88) for corrected calcium. The p value showed a significant drop in both calcium and PTH levels. Although the small size of the sample did not allow a high power for both variables but only one variable, both values were lower at the end of the study which reflects an expected drop in parathyroid function related to the surgical manipulation.

Table 2:Means, standard deviations, minimum and maximum values for each test done before total thyroidectomy and 6 months after the operation.

Discussion

Inadvertent resection, manipulation, or devascularization of parathyroid glands are important complications of thyroidectomy that risk transient or permanent hypoparathyroidism and hypocalcemia [11]. The temporal cut-off between transient and permanent hypoparathyroidism post thyroidectomy varies in the literature, with some studies defining permanent hypoparathyroidism at 6 months post-operatively [12, 13] and others at 1 year [14-16]. The cut-off timepoint used to define permanent hypoparathyroidism in this study is 6-months post operative intervention, as defined by the American Thyroid Association [17]. Resultant hypocalcemia may cause neurologic symptoms of perioral paresthesia, cramps and tetany of muscles, seizure episodes, and cardiac manifestations of prolonged QT syndrome and heart failure if pronounced [11]. Patients with postoperative hypoparathyroidism hypocalcemia report variable impact on quality of life [13].

Our study assessed biochemical changes to parathyroid hormone (PTH), corrected calcium (Cacorr), and vitamin D levels before total thyroidectomy and six months post-operative intervention. Although all patients remained normo-calcemic, there was a statistically significant decrease in mean Cacorr levels at 6 months post-operative intervention compared to baseline preoperative levels. Importantly, there was a relative yet significant decrease in mean PTH levels on a background of non-significant changes to vitamin D levels. Furthermore, there was no significant correlation between Cacorr and thyroid stimulating hormone, eliminating it as a confounding variable. Of note, the patients did not exhibit hypo parathyroid symptomatology and consequently, do not satisfy the definition of parathyroid insufficiency. Post-operative levels of PTH and calcium did not return to baseline at 6 months post intervention, indicating a potential shift in the hormonal baseline and a state of asymptomatic decrease in parathyroid function. PTH insufficiency may be defined as a state manifested by clinical symptoms with laboratory values within normal limits [17]. Although the post hoc power was low for PTH in view of the sample size, it was high for Cacorr level. We believe that despite the sample size, the drop in calcium and PTH is real as results of both values were trending in same direction postoperatively, resulting from an expected reduction in parathyroid function.

Most studies discuss the risk factors and dynamic recovery of overt postoperative hypoparathyroidism and hypocalcemia, with laboratory levels below the respective cut-off values, while others propose perioperative or early postoperative PTH measurements as predictors of long-term hypoparathyroidism and hypocalcemia [16, 18, 19]. Few have investigated long-term changes to normocalcemic hypoparathyroidism in relevant populations, where subclinical hypoparathyroidism is characterized as low PTH levels with normal calcium levels [20], but no studies to our knowledge have explored asymptomatic changes in PTH and calcium levels that remained within normal range. An important emerging concept is to consider relative changes to baseline levels of PTH and calcium, and how this may affect patient health and symptomatology in the long term [21]. Khafif A, et. Al. suggest a relative drop from preoperative levels of 50% of PTH levels within 72 hours post-op is a sensitive and specific predictor of long-term hypocalcemia, with most post-operative values maintained within normal limits [22]. Importantly, the authors considered high PTH levels as “normal” if they maintained normo-calcemia, highlighting the importance of adjusting inferences to individual baseline levels. Furthermore, Cho, J, et. al found relative declines of serum calcium and phosphate by 20% and 40%, respectively, by postoperative day 2 to predict long-term hypoparathyroidism with high specificity [23]. The following study related laboratory values of PTH and serum calcium to patient-reported symptoms and changes in quality of life. Some patients described symptoms of hypocalcemia despite normal biochemical levels which the authors attributed to relative changes from baseline that are insufficient but biochemically “normal” [13].

PTH is produced by chief cells of the parathyroid glands and acts on its respective receptors to modulate calcium homeostasis through an intricate interplay between bone resorption and calcium reabsorption. Vitamin D is activated through PTH signaling in response to low calcium levels to facilitate its intestinal absorption. Homeostasis is maintained by intricate feedback mechanisms that allow tight control of a narrow calcium level range [24]. One study explored the hormonal interplay behind post-thyroidectomy hypocalcemia and proposed a short-lived association between post-operative declines in calcium levels and changes to PTH, calcitonin, and albumin levels. The study focused on hypocalcemia with normal PTH levels and suggests that postoperatively the parathyroid glands may be working maximally but insufficiently so to maintain calcium levels [25]. However, such suggestions do not explain the long-standing apparent rightward shift in the homeostatic baseline seen in our study. It is warranted to explore these “biochemically normal” changes in homeostatic levels of PTH and calcium post-operative intervention and to understand their long-term consequence on patient health and quality of life. We have previously documented, in another prospective study, a significantly long term drop calcium and PTH levels in normocalcemic asymptomatic patients undergoing central neck dissection, while levels remaining within normal range [26]. In the current study, we add that the effect of calcium and PTH is noticed not only in neck dissection but even after simple thyroidectomy. Although in our present study the patients did not exhibit hypoparathyroid symptoms at 6 months post intervention, we expect that, with sufficiently long follow up, we might see a shift in the incidence of pathologies related to calcium metabolism in such a population. Long-term consequences of the PTH shift are unknown on quality of bone, calcium homeostasis, and cardiovascular risks. Therefore, further long-term follow up is recommended. Patients at baseline risk for particular pathologies might be carefully approached when considered for total thyroidectomy.

Acknowledgement

None.

Conflict of Interest

No conflicts of interest.

References

- Feroci F, Rettori M, Borrelli A, Coppola A, Castagnoli A, et al. (2014) A systematic review and meta-analysis of total thyroidectomy versus bilateral subtotal thyroidectomy for Graves' Surgery 155(3): 529-540.

- Cirocchi R, Trastulli S, Randolph J, Guarino S, Di Rocco G, et al. (2015) Total or near-total thyroidectomy versus subtotal thyroidectomy for multinodular non-toxic goitre in adults. The Cochrane database of systematic reviews 2015(8): CD010370.

- Kakava K, Tournis S, Papadakis G, Karelas I, Stampouloglou P, et al. (2016) Postsurgical Hypoparathyroidism: A Systematic Review. In vivo (Athens, Greece) 30(3): 171-179.

- Christou N, Mathonnet M (2013) Complications after total thyroidectomy. Journal of visceral surgery 150(4): 249-256.

- Fan C, Zhou X, Su G, Zhou Y, Su, J, et al. (2019) Risk factors for neck hematoma requiring surgical re-intervention after thyroidectomy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC surgery 19(1): 98 (2019).

- Chahardahmasumi E, Salehidoost R, Amini M, Aminorroaya A, Rezvanian H, et al. (2019) Assessment of the Early and Late Complication after Thyroidectomy. Advanced biomedical research 8: 14.

- Quimby AE, Wells ST, Hearn M, Javidnia H, Johnson-Obaseki S (2017) Is there a group of patients at greater risk for hematoma following thyroidectomy? A systematic review and meta-analysis. The Laryngoscope 127(6): 1483-1490.

- Thomusch O, Machens A, Sekulla C, Ukkat J, Brauckhoff M, et al. (2003) The impact of surgical technique on postoperative hypoparathyroidism in bilateral thyroid surgery: a multivariate analysis of 5846 consecutive patients. Surgery 133(2): 180-185.

- McCullough M, Weber C, Leong C, Sharma J (2013) Safety, efficacy, and cost savings of single parathyroid hormone measurement for risk stratification after total thyroidectomy. The American surgeon 79(8): 768-774.

- Qin Y, Sun W, Wang Z, Dong W, He L, et al. (2021) A meta-analysis of risk factors for transient and permanent hypocalcemia after total thyroidectomy. Frontiers in Oncology 10: 614089.

- Mazotas G, Wang T (2017) The role and timing of parathyroid hormone determination after total thyroidectomy. Gland Surgery 6(1): S38-S48.

- Selberherr A, Scheuba C, Riss P, Niederle B (2015) Postoperative hypoparathyroidism after thyroidectomy: Efficient and cost-effective diagnosis and treatment. Surgery 157(2): 349-353.

- Doubleday A, Robbins S, Macdonald C, Elfenbein D, Connor N, et al. (2021) What is the experience of our patients with transient hypoparathyroidism after total thyroidectomy? Surgery 169(1): 70-76.

- Almiquist M, Hallgrimsson P, Nordenström E, Bergenfelz A (2014) Prediction of Permanent Hypoparathyroidism after Total Thyroidectomy. World Journal of Surgery 38(10): 2613-2620.

- Annebäck M, Hedberg J, Almquist M, Stålberg P, Olov N (2021) Risk of Permanent Hypoparathyroidism After Total Thyroidectomy for Benign Disease: A Nationwide Population-based Cohort Study from Sweden. Annals of Surgery 274(6): e1202-e1208.

- Ritter K, Elfenbein D, Schneider D, Chen H, Sippel R (2015) Hypoparathyroidism after Total Thyroidectomy: Incidence and Resolution. J Sur Res 197(2):348-353.

- Orloff L, Wiseman S, Bernet V, Faheylll T, Shaha A, et al. (2018) American Thyroid Association Statement on Postoperative Hypoparathyroidism: Diagnosis, Prevention, and Management in Adults. Thyroid 28(7): 830-841.

- Edafe O, Antakia R, Laskar N, Uttley L, Balasubramanian S (2014) Systemic review and meta-analysis of predictors of post-thyroidectomy hypocalcaemia. Br J Surg 101(4): 307-320.

- Asari R, Passler C, Kaczirek K, Scheuba C, Niederle B (2008) Hypoparathyroidism After Total Thyroidectomy A Prospective Study. Arch Surg 143(2): 132-137.

- Cusano N, Maalouf N, Wang P, Zhang C, Cremers S, et al. (2013) Normocalcemic Hyperparathyroidism and Hypoparathyroidism in Two Community-Based Nonreferral Populations. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 98(7) 2734-2741.

- Nagel K, Hendricks A, Lenschow C, Meir M, Hahner S, et al. (2022) Definition and diagnosis of postsurgical hypoparathyroidism after thyroid surgery: meta-analysis. BJS Open 6(5): zrac102.

- Khafif A, Pivoarov A, Medina J, Avergel A, Gil Z, et al. (2006) Parathyroid Hormone: A Sensitive Predictor of Hypocalcemia Following Total Thyroidectomy. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 134(6): 907-910.

- Cho J, Park W, Min S (2016) Predictors and risk factors of hypoparathyroidism after total thyroidectomy. Int J Sur 34: 47-52.

- Ja S, Simonds W (2023) Molecular and Clinical Spectrum of Primary Hyperparathyroidism. Endocr Rev 44(5): 779-818.

- Chisthi M, Nair R, Kuttanchettiar K, Yadev I (2017) Mechanisms behind Post-Thyroidectomy Hypocalcemia: Interplay of Calcitonin, Parathormone, and Albumin-A Prospective Study. J Inves Surg 30(4): 217-225.

- Alansari H, Mathur N, Ahmadi H, AlWatban ZH, Alamuddin N, et al. (2024) Outcomes of Central Neck Dissection for Papillary Thyroid Carcinoma in Primary Versus Revision Setting. Indian J Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 76(1): 720-725.

-

Abdulrahman Faeq Alzamil*, Abdullah Omar Aljafaari, Kawther Nermish, Fahad Khalifa Bedawi, Sara Sabra, Dalal Alromaihi, Naji Alamuddin and Omar Sabra. Longitudinal Analysis of Calcium and Parathyroid Hormone Levels in Normocalcemic Patients Following Total Thyroidectomy. On J Otolaryngol & Rhinol. 7(2): 2024. OJOR.MS.ID.000658.

-

Thyroidectomy, PTH levels, Hypoparathyroidism, Parathyroid gland, Vitamin D, Neck dissection, Surgery, Post thyroidectomy, Perioral paresthesia

-

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.