Review Article

Review Article

Invasive Fungal Rhinosinusitis in Pediatric Populations; a Tertiary Hospital Experience

Ali A Al Momen1*, Mohammed R Al Eid2, Eman Almomen3, Abdullah Alshakhs4, Hassan Almomen5 and Mohammed Al Saeed6

1Consultant Rhinology & Skull base surgery, King Fahad Specialist Hospital, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia

2ENT trainee resident, Saudi ORL program, Eastern Region, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia

3Radiology Consultant, Dammam medical complex, Dammam, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia

4Medical intern, King Faisal University, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia

5Clinical pathology Consultant, Dammam Regional laboratory and Blood Bank Kingdom of Saudi Arabia

6Sixth year medical student, AlBaha University, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia

Ali Almomen, Consultant Rhinology & skull base surgery, King Fahad Specialist Hospital Dammam, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia.

Received Date: January 14, 2020; Published Date: January 21, 2020

Abstract

Fungal infection is a well-known and a common cause of sinusitis. Fungal sinusitis is classified into two main categories based on histopathological invasion as: invasive and non-invasive, the invasive form includes acute, chronic, and chronic granulomatous, while the non-invasive include: fungal ball, saprophytic fungal infestation, eosinophilic fungal sinusitis and allergic fungal sinusitis. Usually, Invasive fungal sinusitis is encountered in immunocompromised patients. However, there are many reports which have described these cases with immunocompetent individuals. The purpose of this review article is to summarize our long experience with pediatric patients diagnosed with invasive fungal sinusitis managed at a tertiary referral hospital at King Fahad Specialist Hospital Dammam, KSA and discuss the management and determine the variables that impact the outcome.

Introduction

Fungal infection is a well-known and a common cause of sinusitis. Fungal sinusitis is classified into two main categories based on histopathological invasion as: invasive and non-invasive, the invasive form includes acute, chronic, and chronic granulomatous, while the non-invasive include: saprophytic fungal infestation, fungal ball, allergic fungal sinusitis and eosinophilic fungal sinusitis. Invasive fungal sinusitis is usually encountered in immunocompromised subjects, but some reports have described these forms in immunocompetent individuals. Invasive fungal rhinosinusitis is an opportunistic, serious and quickly progressive disease that has fulminant and deadly outcome if not recognized early and treated aggressively, it mostly affects immunocompromised individuals especially those with hematological-oncological diseases.

Clinically the patients can present with fever, facial pain, nasal congestion, epistaxis, headache, all of which are nonspecific symptoms, but concerns must be raised for any patient with risk factors who develops an acute presentation with these symptoms. clinical and radiological progression is fast in invasive fungal sinusitis, with typical endoscopic appearances such as black crusts, pale mucosa and necrosis. Endoscopic examination of the nose and oral cavity and biopsy of suspicious lesions to be confirmed by histopathological examination, many fungal species contribute to Invasive fungal sinusitis but the most commonly involved are Aspergillus and zygomycete species. Treatment is typically aggressive and includes surgical debridement, parenteral antifungals and control of the underlying cause, however, mortality rate remains high in such cases and is reported between 33-100% in some cases.

Objectives and Goal

The purpose of this review study is to present our experience with pediatric patients who were diagnosed with invasive fungal sinusitis managed and treated at a tertiary referral hospital of King Fahad Specialist Hospital Dammam, KSA and discuss the management and determine the variables that impact the outcome.

Illustrative Cases

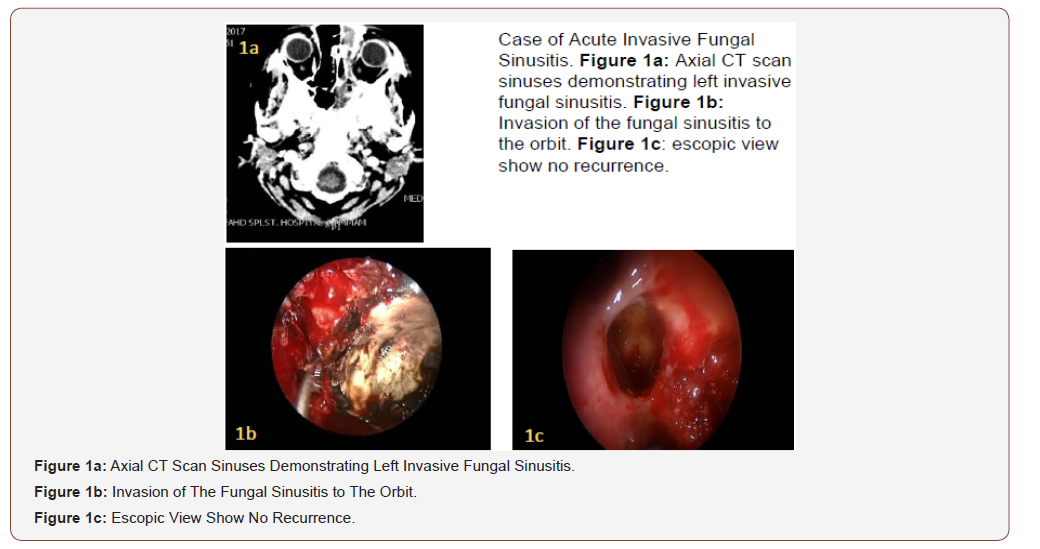

Acute invasive fungal sinusitis

12 years old female, known case of pre-B ALL, was receiving treatment as per Protocol COG 0232, she developed drug-induced diabetes and was started on Insulin therapy, later on she had septic shock for which she needed critical care management, Daunomycin dose was lowered by 50% the recommended dose by the protocol, once the patient stabilized the full dose was resumed, which was followed by another septic shock and transfer to critical care, she developed mixed bacterial infection with Stenotrophomonas, Serratia, Staphylococcus, Enterrobacter and fungal infection with Mucomycosis and Aspergillosis disseminated involving the left orbit, sinus (Figure 1a), lung with cavitation and pleural effusion, liver and spleen with intra-peritoneal abscess and ascites.

She was managed by parenteral antibiotics and antifungals, pleural effusion drainage and several endoscopic sinus surgeries for drainage and debridement of the paranasal sinuses (Figure 1b). On follow up she had no recurrence of fungal sinusitis (Figure 1c), the visual acuity of the left eye has been affected.

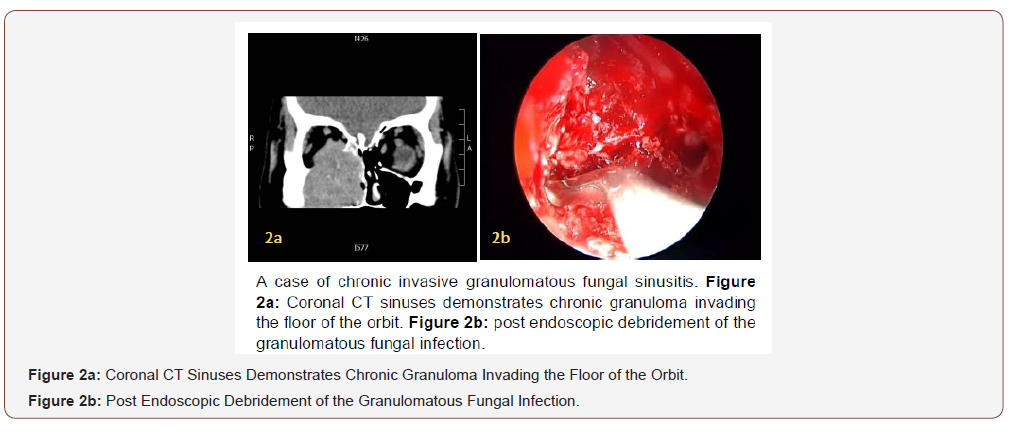

Chronic invasive granulomatous fungal sinusitis

14 years old male, known case of Cerebral Palsy and mental retardation, referred from a private hospital with history of right sided cheek swelling and right proptosis with suspicion of malignant lesion, on examination there was a hard mass in the right maxillary area and the other ear, nose, throat examination were unremarkable. CT scan showed a mass in the right maxillary antrum measuring 5x3 cm with evidence of bone destruction (Figure 2a).

On endoscopic examination there was a compressible bulge on the medial wall of the maxillary sinus and solid granulomatous mas filling the anterior ethmoid, posterior ethmoid and maxillary sinuses, with dehiscence of the medial orbital wall and orbital invasion, Anterior and posterior ethmoidectomy was done and the granulomatous tissue was removed from the middle meatus with debulking of the maxillary sinus (Figure 2b), the tissues were sent for histopathology which confirmed the presence of numerous granulomas featuring epithelioid and multinucleated giant cells and the presence of fungal hyphae within the giant cells and the adjacent connective tissue.

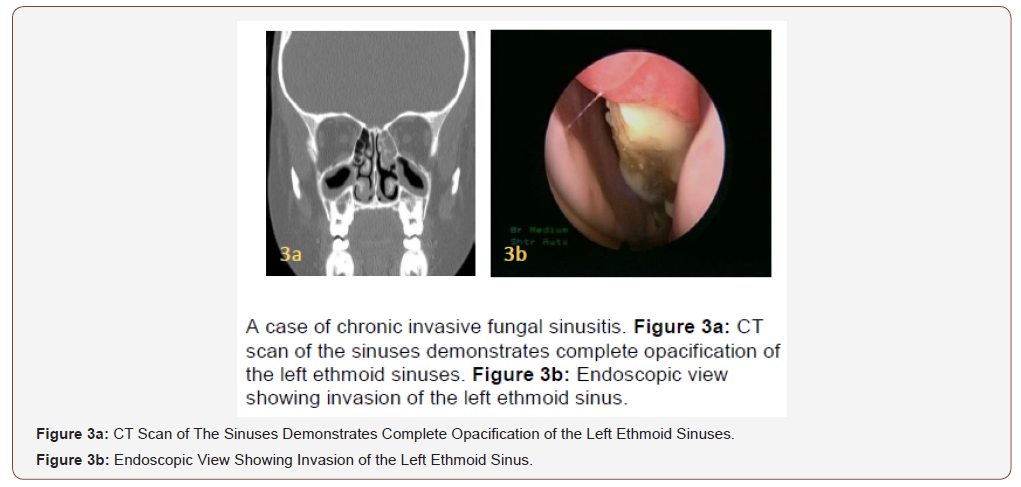

Chronic invasive fungal sinusitis

9 years old female who is diagnosed with Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia was referred to ENT with history of fever, nasal congestion and facial pain, and CT scan showed opacity in the left ethmoid sinus (Figure 3a), endoscopic examination was done under general anesthesia and showed whitish fungal infection invading left ethmoid sinus (Figure 3b), wide endoscopic debridement and removal of fungal sinusitis. Pt was managed by post-operative systemic antifungal for three months and showed no recurrence at follow up.

Discussion

Although there are a lot of confusion regarding the classification, the most accepted classification divides fungal rhinosinusitis into noninvasive and invasive diseases, which typically determined based on histopathological evidence of fungi invasion of the tissue.

The invasive type includes

1) Granulomatous invasive FRS.

2) Acute invasive (fulminant) FRS.

3) Chronic invasive FRS.

The non-invasive diseases include

1) Fungus related eosinophilic FRS that includes AFRS.

2) Fungal ball.

3) Saprophytic fungal infestation.

Acute invasive fungal rhinosinusitis is an opportunistic infection that occurs mostly in immunocompromised patients [1,2,3]. Predisposing conditions include hematological malignancies, uncontrolled diabetes, and AIDS, all of which affect the function of neutrophils [4-6,7,8]. The most common predisposing factor in pediatric group is hematological malignancies, similar to adult patients [8,9]. The most frequent fungal agent in uncontrolled diabetic patients is mucormycosis and in hematologic and oncologic patients the invasive aspergillosis [6,10]. In the described case of Acute invasive fungal Rhinosinusitis, the patient had disseminated fungal infection with both Aspergillosis and Mucormycosis.

The first symptoms of AIFR are generally nonspecific. The most common initial symptoms are fever, facial pain, rhinorrhea and nasal congestion. Persistent fever, cavernous sinus syndrome, or orbital involvement symptoms, facial fullness, skin or mucosal findings like ulcerated necrotic tissues in gingiva or hard palate, or abnormal CT findings and suspicious lesions in nasal cavity should raise suspicion of AIFR [2,11,12]. orbital Cellulitis, proptosis, ophthalmoplegia, and changes in mental ability are the signs of orbital and intracranial involvement. In previous studies, 20-60% of patients had different local symptoms. Alteration in the appearance of nasal mucosa is the most consistent sign of Acute invasive fungal rhinosinusitis. Nasal examination with fiberoptic or rigid endoscopes is indicated in immunocompromised patients with fever of unknown origin or other suspicious symptoms. Mucosal abnormalities such as discoloration, ulceration and granulation can be seen in endoscopic examination. White discoloration of the mucosa indicates tissue ischemia and black discoloration is a late finding of tissue necrosis [12]. Decreased vascularity and sensation of nasal mucosa indicate fungal invasion [13].

Gillespie et al. [12] reported that, the most common locations of mucosal abnormalities were in middle turbinate, septum, hard palate and inferior turbinate in order of frequency. Endoscopic examination must be performed for every patient and tissue specimens should be taken from suspicious lesions. The fiberoptic endoscopes allow detailed visualization of the nasal cavity and detection of early mucosal changes in invasive fungal disease [10].

General anesthesia is sometimes needed to perform this procedure in pediatric patients. This approach also permits more aggressive removal of debris and crust. Extra-sinonasal involvement is a poor prognostic factor for morbidity and mortality. Besides endoscopic nasal examination, a complete, careful head and neck examination should also be performed in all patients. A thorough cranial nerve examination should be performed. periorbital edema can be a sign of rhino cerebral mucormycosis [14,15]. Careful examination of the oral cavity to check for palatal and buccal involvement. involvement of the palatine arteries can lead to unilateral gangrene and perforation of the hard and soft palates. CT should be performed in patients with AIFR suspicion. At the early stage of disease, CT has high sensitivity and low specificity for mucormycosis. Severe soft tissue inflammation of unilateral nasal cavity is the most consistent early CT finding [16]. Bone erosion, facial cellulitis, orbital involvement are the findings of the advanced stage disease and highly suggestive for invasive fungal sinusitis [16]. MRI should be performed to evaluate intracranial and orbital extension of disease.

Mental status changes, seizure and stroke can be the signs of intracranial involvement. In a study of Howells and Ramadan [17] MRI was proposed to be the initial radiologic procedure in AIFR patients because of the low specificity and underestimation of the disease on CT scan. Diagnosis of AIFR requires culture and histological examination of the biopsy material, besides clinical suspicion. The microscopic findings are tissue necrosis with minimal host inflammatory cell infiltration, hyphal forms within submucosa and angiocentric invasion [18]. Each fungus has specific types of hyphae. Mucormycosis shows broad, ribbon like irregular and nonseptate hyphae, whereas Aspergillus sp. demonstrate septate and narrow hyphae [19]. It is known that, mucormycosis may also be combined with other fungal infections such as aspergillosis [14]. Biopsies taken from granulations, discolored and ulcerated tissues during nasal endoscopy can provide histological diagnosis. For Patients suspected for AIFR without typical endoscopic findings, biopsies can be taken from the most frequent sites such as septum, inferior and middle turbinate.

Frozen section biopsy can be considered in acute invasive fungal rhinosinusitis as late diagnosis can lead to fatal consequences. Ghadiali et al. [3] emphasized the importance of frozen section biopsy in patients suspected to have acute invasive fungal rhinosinusitis. The usage of this technique during operation can also prevent further iatrogenic morbidities and avoid radical surgeries [3]. Nonspecific anti-fungal agents can be used in this technique because the fungal agent cannot be identified with certainty sometimes. The gold standard test for diagnosis of the subspecies of invasive fungus is fungal culture. Microbiologic cultures of affected tissue may demonstrate growth of fungal colonies. Culture also gives the chance to perform antibiogram to determine the proper antifungal agent, but the slow growth of fungal colonies limits the use of culture as a diagnostic tool. Sensitivity of fungal cultures is reportedly between 30% and 54% in the literature.

Surgery is the main treatment modality of AIFR, either endoscopically or with open technique. Patients benefit from surgery in various ways:

A. decreases the progression of the disease which allows the bone marrow to recover.

B. fungal load is reduced, which in turn, reduces the burden on recovering neutrophils, and may improve the immunologic status.

C. prevention of easy growth of fungus in devitalized tissue.

D. enhances the ability of antifungal drugs to reach infected areas.

E. nasal irrigation and postoperative monitoring for recurrent disease is facilitated.

F. specimens for culture is provided and detailed histopathological examination is performed [12,13,19].

Turner et al found that surgery, regardless of approach, was an independent predictor for improved survival in patients with AIFS. In the univariate model, those patients who underwent endoscopic resection had improved survival (63.54%) compared to those who received open surgery (54.08%) [20] Green et al [21]. In the largest case series of pediatric Invasive fungal sinusitis.

In the literature, reported a mortality rate of 14.3%, which is significantly lower than the historic data, and suggesting that careful observation of clinical changes and a high index of suspicion leading to early diagnosis and treatment are important positive prognostic factors. Endoscopic procedures are usually adequate for debridement at the early stages of disease. However, in advanced situations; maxillectomy, facial resection, or orbital exenteration might be necessary. Necrotic tissues debridement should be continued until soft tissue surfaces and bleeding bone are reached. Endoscopic resection of turbinates and septum can be performed at patients with local disease. Minor debridement can be performed without histopathological diagnosis, but it is essential for radical procedures like facial resection or maxillectomy [13].

Chronic Granulomatous Invasive Fungal sinusitis typically affects immunocompetent patients, it is caused in most cases by Aspergillus Flavus which is mostly observed in cases in India, Pakistan and Sudan. A different variety of fungal species, Aspergillus Fumigatus has been reported in north America. Most common presenting symptom of CGIFS is unilateral proptosis [11]. Other symptoms at the time of presentation include severe nasal congestion/obstruction, sinus pain/pressure, headaches, and facial numbness [11,22]. Physical exam findings include unilateral proptosis, numbness over the V2 distribution, congested mucosa, and polypoid changes to the mucosa on nasal endoscopy. In our case the patient had right sided proptosis with a hard mass in the right maxillary area. Studies have shown that CGIFS typically is Odense or hyperdense to muscle tissue on CT scans, is unilateral, and generally is present in only 1 to 2 sinuses [23,24]. As opposed to allergic fungal rhinosinusitis, the appearance is homogenous and extra sinus involvement is greater than intra sinus [23].

Bony erosion is typically present. MRI should be ordered when orbital or intracranial involvement is suspected. CGIFS is isointense on T1-weighted images and hypointense on T2-weighted images [23,24]. Histopathology showing noncaseating granulomas with fungal hyphae within giant cells of the granulomas with invasion into mucosa, submucosa, blood vessels, or bone confirms the diagnosis [1,11,4]. Surrounding tissue typically shows a mild amount of inflammation consisting of eosinophils, lymphocytes, and plasma cells in a setting of dense fibrosis [1,4]. There is no consensus on the best course of treatment for CGIFS; however, most authors agree that both surgery and antifungals play a role. aggressive surgical resection and intravenous amphotericin B have been most widely used. In more recent reports, authors have suggested the removal of “as much disease as possible” and concluded that surgical intervention should ultimately be individually based on the extent of disease [5,11].

Halderman et al reported a case of chronic granulomatous invasive fungal sinusitis with extensive disease and both orbital and intracranial involvement which was successfully treated with conservative surgery and long-term oral Voriconazole, and the patient remained disease free 16 months after treatment, he recommended conservative treatment to be considered even for extensive disease. Tae Hoon Kim et al also reported a case of with chronic granulomatous invasive fungal sinusitis affecting the left side and extending into the pterygopalatine fossa and orbital floor, it was treated by left partial maxillectomy followed by systemic antifungals starting with Amphotericin B for 10 days then switching to Itraconazole for 80 days , the patient was followed for 18 months after treatment and showed no signs of recurrence, the authors suggested the treatment to be combination of surgery and antifungal agents rather than surgery alone to achieve optimal outcomes.

The CIFS subtype was noted to have an association with diabetes mellitus, immunocompromised patients, and a lack of granuloma formation in the tissues. The fungal species involved were nearly exclusively Aspergillus fumigatus. This is in contrast to CGIFS characterized by Aspergillus flavus species, granuloma formation, and immunocompetent patients [10,13]. the treatment of both chronic invasive forms of fungal disease (CIFS and CGIFS) parallel their slow progression. This study highlights the benefits of endoscopic-directed management with limited resection of surrounding tissues. CIFS is a less aggressive infection and preservation of tissue function should take a higher priority. Usually, Patients present with non-specific signs and symptoms and have a very slow clinical course. Therefore, they are usually associated with late diagnosis, which may lead to significant morbidity [4]. In spite of insufficient comparative data, no significant differences in disease outcomes have been documented [1].

The treatment of both forms is similar [23]. The distinction between non granulomatous and granulomatous form of chronic invasive FRS is significantly based on pathological findings [1]. The granulomatous form presents as submucosal noncaseating granuloma consisting of Langhans-type giant cells or foreign body. The hyphae of the fungus are usually sparse with extensive fibrosis. In contrast, in no granulomatous type there is a dense accumulation of hyphae, but the inflammatory infiltrate is sparse [4]. The majority of cases of chronic invasive FRS in the literature have been documented from developing countries, usually located in the tropical regions of Middle East, South Asia, South America, and Africa [6]. The humid and hot climate in these regions creates a suitable environment for proliferation of fungal spores and fungal growth. In addition, the high number of individuals working in agricultural activities increases the risk of intense exposure to fungal spores.

The usual treatment of invasive fungal rhinosinusitis, including both chronic and acute forms, requires an effective systemic antifungal therapy and surgical debridement [23]. The role of the surgery is to provide sufficient ventilation to sinus to facilitate the penetration of antifungal agents by the removal of devitalized tissues. Posaconazole, amphotericin B, voriconazole, itraconazole, and caspofungin are antifungal agents that are effective against Aspergillus species [10].

Conclusion

Pediatric Invasive fungal sinusitis is usually encountered in immunocompromised subjects. Pediatric Invasive fungal rhinosinusitis is an opportunistic, serious and quickly progressive disease that has fulminant and deadly outcome if not recognized early and treated aggressively. Clinically the patients can present with fever, facial pain, nasal congestion, epistaxis, headache, all of which are non-specific symptoms, but concerns must be raised for any patient with risk factors who develops an acute presentation with these symptoms. Treatment is typically aggressive and includes surgical debridement, parenteral antifungals and control of the underlying cause, however, mortality rate remains high in the pediatric populations.

Acknowledgement

None.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interests.

References

- Tarkan O, Karagün B, Özdemir S, Tuncer Ü, Sürmelioğlu Ö, et al. (2012) Endonasal treatment of acute invasive fungal rhinosinusitis in immunocompromised pediatric hematology oncology patients. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol 76(10): 1458-1464.

- AH Park, HR Muntz, ME Smith, Z Afify, T Pysher, et al. (2005) Pediatric invasive fungal rhinosinusitis in immunocompromised children with cancer. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 133: 411-416.

- MT Ghadiali, NA Deckard, U Farooq, F Astor, P Robinson, et al. (2007) Frozen section biopsy analysis for acute invasive fungal rhinosinusitis. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 136: 714-719.

- S Mohindra, R Gupta, J Bakshi, SK Gupta (2007) Rhinocerebral mucormycosis: the disease spectrum in 27 patients. Mycoses 50: 290-296.

- C Sundaram, A Mahadevan, V Laxmi, TC Yasha, V Santosh, et al. (2005) Cerebral zygomycosis, Mycoses 48: 396-407.

- SL Parikh, G Venkatraman, JM DelGaudio (2004) Invasive fungal sinusitis: a 15-year review from a single institution. Am J Rhinol 18(2): 75-81.

- C Hejny, JB Kerrison, NJ Newman, CM Stone (2001) Rhino-orbital mucormycosis in a patient with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) and neutropenia. Am J Ophthalmol 132: 111-112.

- L Pagano, P Ricci, A Tonso, A Nosari, L Cudillo, et al. (1997) Mucormycosis in patients with hematological malignancies: a retrospective clinical study of 37 cases. GIMEMA Infection Program (Gruppo Italiano Malattie Ematologiche Maligne dell'Adulto). Br J Haematol 99: 331-336.

- K Scheckenbach, O Cornely, TK Hoffmann, R Engers, H Bier, et al. (2010) Emerging therapeutic options in fulminant invasive rhinocerebral mucormycosis. Auris Nasus Larynx 37(3): 322-328.

- R Eliashar, IB Resnick, A Goldfarb, J Wohlgelernter, M Gross (2007) Endoscopic surgery for sinonasal invasive aspergillosis in bone marrow transplantation patients. Laryngoscope 117: 78-81.

- F Kasapoglu, H Coskun, OA Ozmen, H Akalin, B Ener (2010) Acute invasive fungal rhinosinusitis: evaluation of 26 patients treated with endonasal or open surgical procedures. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 143: 614-620.

- MB Gillespie, BW O Malley, HW Francis (1998) An approach to fulminant invasive fungal rhinosinusitis in the immunocompromised host. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 124: 520-526.

- Süslü AE, Oğretmenoğlu O, Süslü N, Yücel OT, Onerci TM (2009) Acute invasive fungal rhinosinusitis: our experience with 19 patients. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol 266: 77-82.

- MB Gillespie, O Malley BW (2000) An algorithmic approach to the diagnosis and management of invasive fungal rhinosinusitis in the immunocompromised patient. Otolaryngol Clin North Am 33: 323-334.

- I Ketenci, Y Unlu, H Kaya, MA Somdas, O Kontas, et al. (2011) Rhinocerebral mucormycosis: experience in 14 patients. J Laryngol Otol 125(8): e3.

- JM DelGaudio, RE Swain, TT Kingdom, S Muller, PA Hudgins (2003) Computed tomographic findings in patients with invasive fungal sinusitis. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 129: 236-240.

- RC Howells, HH Ramadan (2001) Usefulness of computed tomography and magnetic resonance in fulminant invasive fungal rhinosinusitis. Am J Rhinol 15: 255-261.

- RD deShazo (1998) Fungal sinusitis. Am J Med Sci 316: 39-45.

- DS Samadi, AN Goldberg, RR Orlandi (2001) Granulocyte transfusion in the management of fulminant invasive fungal rhinosinusitis. Am J Rhinol 15: 263-265.

- Turner JH (2013) Survival outcomes in acute invasive fungal sinusitis: A systematic review and quantitative synthesis of published evidence. Laryngoscope 123(5): 1112-1118.

- Green KK, Barham HP, Allen GC, Chan KH (2016) Prognostic Factors in the Outcome of Invasive Fungal Sinusitis in a Pediatric Population. Pediatr Infect Dis J 35(4): 384-386.

- CF Decker (1999) Sinusitis in the immunocompromised host. Curr Infect Dis Rep 1: 27-32.

- S Arndt, A Aschendorff, M Echternach, TD Daemmrich, W Maier (2009) Rhino-orbitalcerebral mucormycosis and aspergillosis: differential diagnosis and treatment. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol 266: 71-76.

- BJ Ferguson (2000) Mucormycosis of the nose and paranasal sinuses. Otolaryngol Clin North Am 33(2): 349-365.

-

Ali A Al Momen, Mohammed R Al Eid, Eman Almomen, Abdullah Alshakhs, Hassan Almomen, et al. Invasive Fungal Rhinosinusitis in Pediatric Populations; a Tertiary Hospital Experience. On J Otolaryngol & Rhinol. 2(1): 2020. OJOR.MS.ID.000529.

-

Fungal sinusitis, Chronic granulomatous, Rhinosinusitis, Oncological diseases, Pleural effusion, Paranasal sinus, Granulomatous, Nasal congestion, Facial pain, Aspergillosis.

-

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.