Case Report

Case Report

Frontal Sinus Cerebrospinal Fluid Fistula in A Crouzon Syndrome Patient

Bernard Soccol Beraldin* and Vanessa Gehrke

Federal University of Health Sciences of Porto Alegre (UFCSPA)-Santa Casa de Misericórdia de Porto Alegre, RS, Brazil

Bernard Soccol Beraldin, Federal University of Health Sciences of Porto Alegre (UFCSPA)-Santa Casa de Misericórdia de Porto Alegre, RS, Brazil.

Received Date: September 30, 2022; Published Date: December 16, 2022

Introduction

Cerebrospinal fluid leakage is caused by an abnormal communication between the subarachnoid space and the nasal cavity [1]. The most common etiologies of cerebrospinal fistula are traumatic, iatrogenic, idiopathic or resulting from neoplasia.

Skull base fractures represent up to 80% of the causes of cerebrospinal fluid leakage [2] and are complications of highimpact trauma, which can generate cerebrospinal fistula, due to the vulnerability of its anatomical limits [3].

About 16% of the causes of cerebrospinal fistula correspond to iatrogenic injury, and the most common sites during endoscopic intervention are the cribriform plate/ethmoidal fovea, approximately 80%, followed by the frontal sinus and sphenoid sinus [2].

The clinical presentation of Cerebrospinal fluid rhinorrhea is intermittent unilateral drainage, usually positional and exacerbated by head movement [1, 2]. Sometimes sweet/salty post nasal drainage may be reported by the patient. In patients with posttraumatic fistula, the diagnosis can be facilitated by the presence of periorbital ecchymosis, epistaxis, visual changes, anosmia and pneumoencephalus. Chronic conditions, on the other hand, are more difficult to identify, since symptoms are rare and often accounted to other diagnoses such as allergic or vasomotor rhinitis.

Delay in diagnosis increases the risk of complications such as meningitis and brain abscess [2]. When suspected of having a fistula, detailed anamnesis and nasal endoscopy are essential for evaluation [1]. Diagnostic tests, such as beta-2 transferrin and betatrace protein, also help to confirm the diagnosis, since they have high sensitivity and specificity, the latter being more specific [1, 2]. High-resolution computed tomography can accurately define the site of the fistula and is an essential tool for evaluation [1].

Endoscopic treatment of Cerebrospinal fluid fistula of the frontal sinus has become the gold standard, as it has high success rates and low morbidity. External approaches, on the other hand, present excellent visualization and access to the frontal sinus, but have a higher rate of complications such as cerebral edema, intracerebral hemorrhage, anosmia, frontal lobe déficit and mucocele formation [4]. Proper access and precise localization of the defect, but not the type of graft used for repair, appear to be essential for surgical success [1, 4].

Case Report

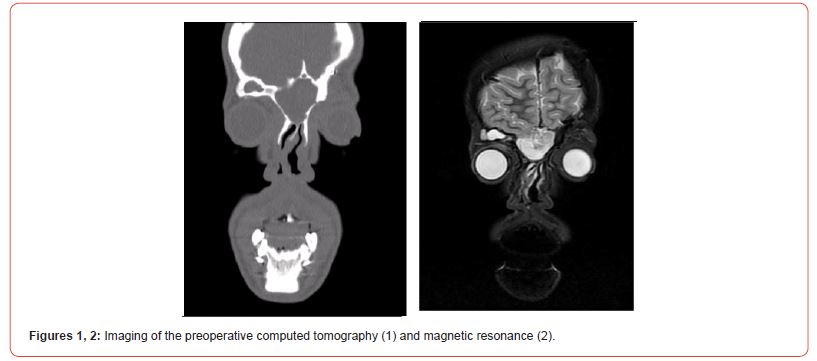

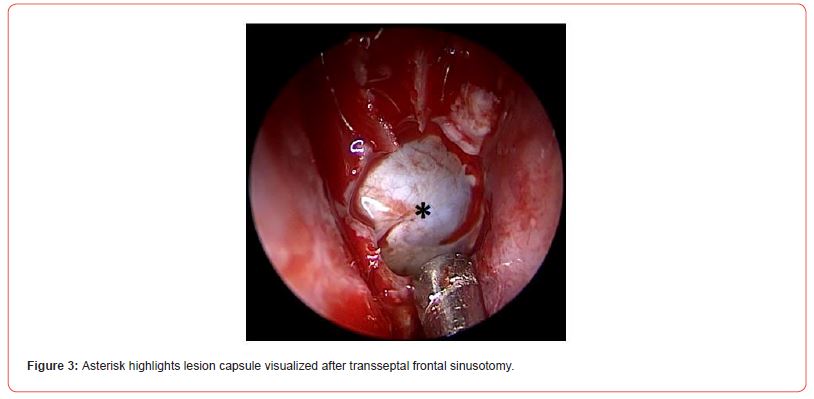

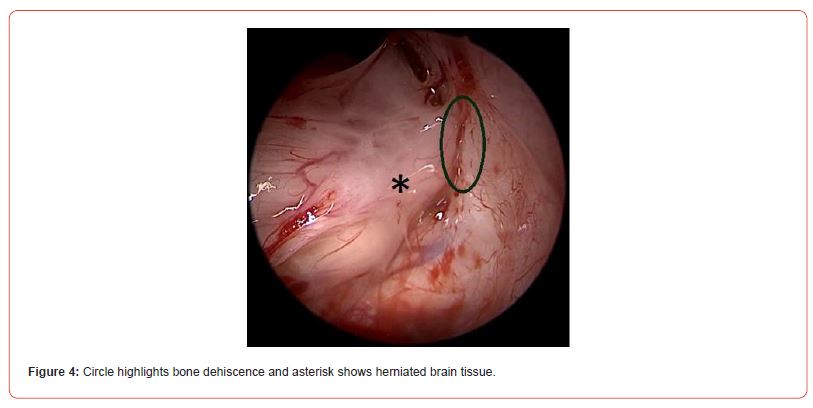

A 17-year-old male patient, with crouzon syndrome and history of multiple craniomaxillofacial interventions, presented cranioencephalic trauma in childhood due to a fall from his own height, which resulted in a cerebrospinal fluid leakage, being treated with conservative measures and achieving complete clinical improvement. Years later, he underwent computed tomography (Figure 1) to plan a new surgery for craniofacial advancement, where a suspicious alteration of mucocele in the frontal sinus was visualized. He was referred to an otorhinolaryngologist, the evaluation was complemented with magnetic resonance imaging (Figure 2) and nasal endoscopic surgery was indicated. A bilateral endonasal frontal sinusectomy was performed via the transseptal approach, with visualization of a discreet purulent secretion immediately anterior to the lesion capsule (Figure 3). After opening the lesion, cerebrospinal fluid drainage of a possible meningoencephalocele was observed and, later, dehiscence in the lateral frontal region on the left (Figure 4). Closure of the cerebrospinal fluid fistula was performed with a free graft from the middle turbinate, fibrin glue and surgical, and a tampon was made for containment. Patient evolved well during hospitalization, performing complementary measures for fistula treatment. He was discharged asymptomatic, with instructions to maintain relative rest, not to exert, perform nasal rinsing and take amoxicillin with clavulanate. On the seventh day after discharge, he presented gastrointestinal symptoms, such as vomiting, evolving with liquorrhea and returning to the hospital. Nasal endoscopy confirmed recurrence of the fistula. He was submitted to a new intervention, with low output cerebrospinal fluid drainage. Enlargement of the frontal sinusectomy and correction of the fistula was performed using fibrin glue and fat, associated with lumbostomy. During hospitalization, he maintained conservative measures, with excellent evolution. Lumbostomy was maintained until the 5th postoperative day. Currently, he has been followed up as an outpatient and has been asymptomatic for a year.

Discussion

Patients with craniofacial craniosynostosis, as in Crouzon and Apert syndrome, have a congenital predisposition to cerebrospinal fistula. In addition, craniomaxillofacial procedures, to which they are usually submitted, add an iatrogenic risk to the formation of fistulas and meningoencephaloceles [5, 6]. Craniosynostosis alters the position of the cribriform plate and anterior base of the skull, causing a reduction in the frontal process of the maxilla, greater vertical tilt and less orbital depth, reduction of the medial wall of the orbit, and expansion of the ethmoid [6].

Crouzon syndrome is an autosomal dominant syndrome and is characterized by the triad: craniosynostosis, exophthalmos, and midface hypoplasia [5]. It is suggested that 63% of patients with Crouzon syndrome have increased intracranial pressure. Factors that may contribute to this are the potential complications of the syndrome, such as intracranial venous congestion, hydrocephalus and obstructive sleep apnea [5]. Craniosynostosis and high intracranial pressure can lead to an inferior position of the cribriform plate and thinning of the anterior base of the skull.

Meningoencephalocele is defined as a herniation of the meninges and brain from the cranial cavity, usually of congenital origin. It is described as a rare complication of subcranial midfacial advancement [6]. In a patient with Crouzon syndrome, nasofrontoethmoidal osteotomy may cause dural rupture, cerebrospinal fluid leakage, and meningoencephalocele [5, 6]. Many studies show a low rate of recurrence and complications in endonasal endoscopic cerebrospinal fluid correction procedures, being considered the preferred technique. Elevated intracranial pressure is considered to be associated with recurrence and, for this reason, many authors advocate the placement of lumbar drains associated with the surgical approach, although the literature is ambiguous as to its effectiveness. For the surgical approach of a patient with craniosynostosis, the tomographic study, especially in the sagittal section, aids in the prevention of fistula and meningoencephalocele [6].

Conclusion

With this case, we learned that the evaluation of patients with craniofacial craniosynostosis, for surgical planning and postoperative care, must be carried out judiciously, as these patients have a congenital predisposition to cerebrospinal fistula and that the craniomaxillofacial procedures, to which they are usually submitted, add iatrogenic risk to the formation of fistulas and meningoencephaloceles. A multidisciplinary evaluation from otolaryngologists, neurosurgeons and radiologists is essential for the correct management of these cases.

Acknowledgement

None.

Conflict of Interest

No conflict of interest.

References

- Majhi S, Sharma A (2019) Outcome of Endoscopic Cerebrospinal Fluid Rhinorrhoea Repair: An Institutional Study. Indian J Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 71(1): 76-80.

- Le C, Strong EB, Luu Q (2016) Management of Anterior Skull Base Cerebrospinal Fluid Leaks. J Neurol Surg B Base 77(5): 404-411.

- Van Zele T, Dewaele F (2016) Traumatic CSF leaks of the anterior skull base. B-ENT Suppl 26(2): 19-27.

- Gâta A, Trombitas VE, Albu S (2020) Endoscopic management of frontal sinus CSF leaks. Braz J Otorhinolaryngol 88(4): 576-583.

- Panuganti BA, Leach M, Antisdel J (2015) Bilateral meningoencephaloceles with cerebrospinal fluid rhinorrhea after facial advancement in the Crouzon syndrome. Allergy Rhinol (Providence) 6(2): 138-142.

- Ridgway EB, Ropper AE, Mulliken JB, Padwa BL, Goumnerova LC (2010) Meningoencephalocele: a late complication of Le Fort III midfacial advancement in a patient with Crouzon syndrome. J Neurosurg Pediatr 6(4): 368-371.

-

Bernard Soccol Beraldin* and Vanessa Gehrke. Frontal Sinus Cerebrospinal Fluid Fistula in A Crouzon Syndrome Patient. On J Otolaryngol & Rhinol. 6(1): 2022. OJOR.MS.ID.000627.

-

Frontal sinus, Nasal cavity, Sphenoid sinus, Pneumoencephalus, Chronic conditions, Vasomotor rhinitis, Sinusectomy, Craniomaxillofacial procedures, Skull, Cranial cavity.

-

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.