Research Article

Research Article

Evaluation of Saccular Function with cVEMP In Patients with Systemic Lupus Erythematosus

Tuba Turkman*

Department of Otorhinolaryngology, Firat University School of Medicine, Turkey

Tuba Turkman, Department of Otorhinolaryngology, Firat University School of Medicine, Elazığ, Turkey.

Received Date: July 16, 2020; Published Date: September 14, 2020

Abstract

Introduction: Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) is a disease characterized by sensorineural hearing loss, tinnitus and vestibular disorders. Studies have shown that vestibular symptoms are quite common in patients with SLE. The aim of this study was to evaluate the relationship between cervical vestibular evoked myogenic potential (cVEMP) test and saccular dysfunction and the possible relationship between SLE and vertigo in patients with SLE.

Materials and methods: Forty-six SLE patients (aged 18-40 years) and forty healthy volunteers (aged 20-40 years) were included in the study. Patients with SLE were questioned about their duration of the disease, hearing status and balance. Pure-tone audiometry, tympanometry and cVEMP tests were performed to all patients in SLE and control groups.

Results: When P1 and N1 latencies were compared by the cVEMP in SLE and control groups, P1 and N1 latencies of the left and right ears of the SLE group were found to be significantly longer than the control group (p <0.05). In twenty-six SLE patients with vertigo, P1 and N1 latencies were significantly longer than patients with SLE without vertigo. There was also a significant relationship between vertigo and duration of the disease (p <0.05). It was found that the rates of saccular dysfunction were higher in patients with SLE.

Conclusion: This study showed a strong association between the balance disorders and SLE which is an autoimmune disease. Patients with SLE had a higher rate of saccular dysfunction, and there was a significant relationship between duration of the disease and vertigo.

Keywords: Systemic lupus erythematosus; Saccular function; cVEMP

Introduction

Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) is an idiopathic, chronic, autoimmune connective tissue disease that may affect all organs and systems. The disease usually begins between 16-55 years of age and the rate of prevalence among women and men is 1/9-10 [1]. In SLE patients, sensorineural hearing loss and ear symptoms were first identified by Kastanioudakis et al. [2] and Sperling et al. [3]. In patients with SLE, sensorineural hearing loss, tinnitus and vestibular disorders have been detected [4,5]. The clinical presentation of SLE may be moderate or severe. All organs are susceptible to the disease during the process [6]. In a questionnaire, the frequency of audio vestibular symptoms, including vertigo, has been found significantly higher in SLE patients than the control subjects [7,8]. In a histopathological study, the mean density of type I cells in peripheral vestibular sensory epithelium has been found significantly lower in patients with SLE [9]. The production of humoral antibody, immune complexes and autoantibodies circulating in SLE are the main causes of organ damage. The presence of vasculitis in the stria vascularis, spiral ligament and internal auditory artery may cause otologic symptoms [3].

The aim of this study was to evaluate the frequency of vertigo and saccular function with cervical vestibular evoked myogenic potential (cVEMP) test in patients with normal hearing who were diagnosed with SLE and had no other systemic disease.

Materials and Methods

This study was carried out with the consent of the cases in the Audiology Unit of the Department of Otorhinolaryngology. The ethics committee approval was obtained with the decision of the Ethics Committee of the Research on Humans to be held on people, dated 20/11/2018 and numbered 294626. Forty-four SLE patients between 18-40 years (mean 33.18±6.5 years) and forty healthy volunteers between 20-40 years (mean 31.3±6.2) were included in the study [10]. All patients were administered with steroid + hydroxychloroquine. Patients with SLE were divided into three groups according to the duration of the disease (Group 1: 1-5 years, Group 2: 6-10 years, Group 3: 11 years and above).

The inclusion criteria for the SLE groups were the definitive diagnosis of SLE, normal otological findings, immittance audiometry levels in normal range, bilateral acoustic reflexes and having a pure-tone average (PTA) within normal range [11]. The inclusion criteria for the control group were the absence of any known systemic and chronic diseases, normal otological findings, immittance audiometry levels in normal range, bilateral acoustic reflexes and having a pure tone average within normal range [11]. All of the patients in the SLE group and control group underwent ear examination, pure-tone audiometry, tympanometry and cVEMP tests. The duration of the disease, hearing status and vertigo in SLE patients were recorded.

Performing and recording of cVEMP test

In cVEMP tests; two separate waveforms were obtained and recorded by averaging 250 responses to the stimuli delivered at the repetition rate of 7.1/sec with an intensity level of 105dB nHL using the click stimulus at alternating polarity, 80 msec recording range, 10 Hz / 1kHz filter interval. In cVEMP measurements, Medelec Brand Synergy Model ABR device (Natus, A.B.D.) and standard intra-auricular TDH-49P headphones were used.

During recording, the gold-plated disc electrodes were placed as follows; the active electrode in the middle of the sternocleidomastoid (SCM) muscle, the reference electrode on the sternoclavicular joint where the SCM muscle attached to the sternum, and the ground electrode at the center of the forehead. During the application, the patient was asked to turn the head to the opposite side of the ear to be tested during the test while sitting. The impedance difference between the electrodes was below 3 kΩ. In our study, the change rate of mean peak latencies of P1-N1 biphasic waves were evaluated according to the ears, age, duration of disease and presence of vertigo with a stimulus delivered with a repetition rate of 7.1/sec and intensity level of 105 dB nHL.

Statistical analyses

The data were first transferred to Microsoft Office Excel and analyzed using SPSS 22.0 (IBM Corp. Released 2013. IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 22.0. Armonk, NY, USA) program. Categorical measurements were summarized as numbers and percentages, and numerical measurements as mean and standard deviation (median and minimum-maximum where necessary). The Kolmogorov Smirnov test was used to determine whether the variables showed normal distribution according to the groups. Independent Samples T test was used to compare numerical measurements between groups. Dependent T-test (paired t-test) was used to compare dependent numerical measurements. Kruskal Wallis test was used for general comparison between groups with more than two numerical measurements which are not normally distributed for the cases that were significant in this comparison, Bonferroni-corrected Mann-Whitney U-test was used for pairwise comparison of groups. The Pearson Correlation Coefficient and the corresponding p-value were obtained to examine the interaction between the numerical measurements. Statistical significance level was taken as 0.05 in all tests.

Results

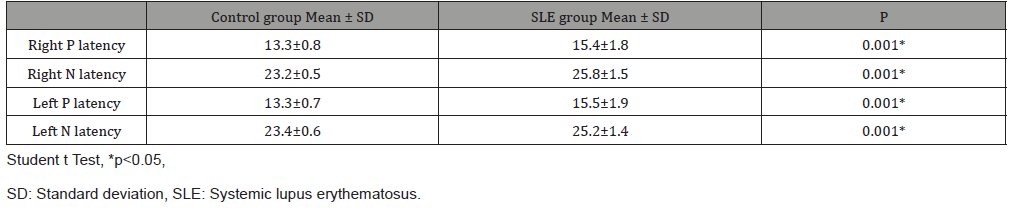

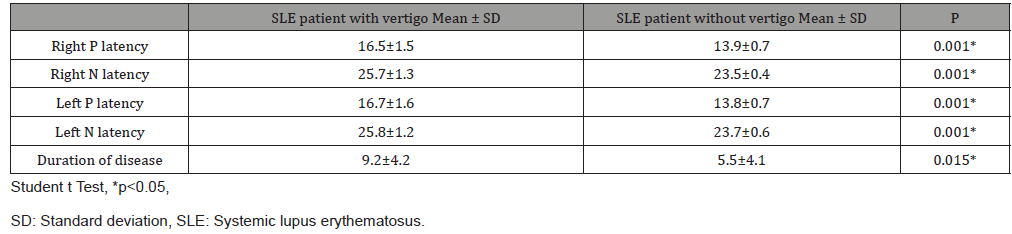

Forty-four SLE patients and forty healthy volunteers were included in the study. No statistically significant difference was observed between the study and control groups in terms of patient ages. The disease duration of patients in the SLE group was between 1-25 years. The cVEMP results of the patients with 1-5 years, 6-10 years and 11 years and above of disease duration were evaluated. When P1/N1 latencies of SLE and control groups were compared, it was observed that the P1/N1 latencies of the right and left ears of the patients with SLE were significantly longer than the control group (p <0.05) (Table 1). No difference was found between right and left ear latencies of SLE patients and control group. In the SLE group, 26 (59%) of the 44 patients had vertigo. The P1 and N1 latencies were significantly longer in SLE patients with vertigo than those without vertigo. There was also a significant relationship between vertigo and disease duration (p <0.05) (Table 2).

Table 1: Comparison of VEMP latencies between groups.

Table 2: Comparison of latencies and duration of disease in SLE patients with and without vertigo.

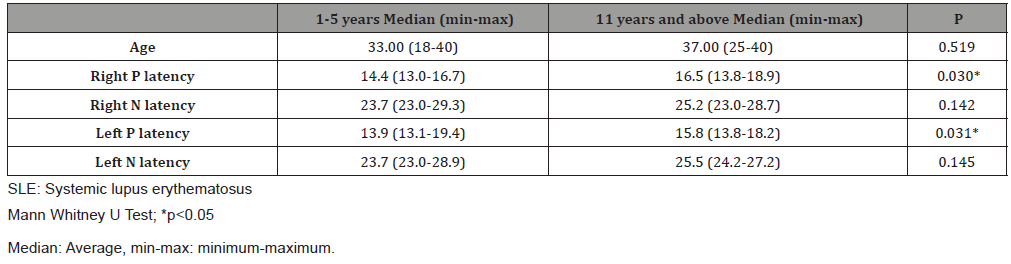

Patients with SLE were compared according to the duration of the disease [(1-5 years), (6-10 years), (11 years and above)], age, and P1/N1 latencies. No significant difference was observed between the groups by means of age. There was a significant difference between P1-N1 latencies and the duration of the disease in the right ear (p <0.05). It was observed that P1 latencies were prolonged significantly among the patients between the ages of 1-5 years and 11 years according to the duration of the disease. No significant difference was observed in N1 latencies (Table 3).

Table 3: Comparison of P1/N1 latencies of the SLE patients according to age and duration of disease.

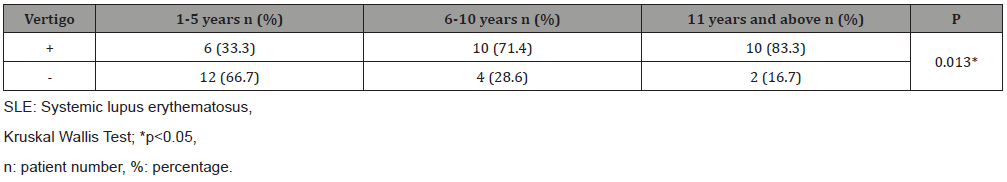

Table 4: Evaluation of the frequency of vertigo in SLE patients according to disease duration.

When the groups were compared in terms of duration of the disease and frequency of vertigo, 6/18 (33.3%), 10/14 (71%) and 10/12 (83%) patients with a duration of disease between 1 and 5 years, 6-10 years, and 11 years and above had vertigo, respectively. It was found that the frequency of vertigo increased as the duration of the disease increased (Table 4).

Discussion

SLE is an extremely complex and multifactorial autoimmune disease with unknown etiology, caused by various genetic and environmental factors, characterized by the presence of autoantibodies, involving multiple organs [12]. Several studies have shown that vasculitis develops in the capillaries and arterioles due to autoimmune complex accumulation. Temporal bone studies have reported the presence of antiphospholipid syndrome and vascular thrombosis mechanisms that cause the accumulation of free radicals in the cochlea and stria vascularis [13]. Ear-related symptoms of SLE are chronic otitis media, progressive sensorineural hearing loss and vertigo. Viral infections, vascular lesions and immune mechanisms can all be effective in internal ear damage [14]. In addition, if the levels of circulating DNA-anti-DNA exceeds the level of cleansing capacity of the immune complexes, these immune complexes can accumulate in various tissues, including glomerulus, and may cause local damage [15].

Vestibular symptoms are quite common in patients with SLE [16]. In addition, the presence of audio vestibular disorder, endolymphatic and cochlear hydrops in patients with SLE have also been reported [17,18]. A strong relationship between SLE and balance disorders has been suggested, but the association of vestibular system in patients with SLE has not been fully investigated [19]. In our study, vertigo status and duration of the disease were investigated in patients with SLE and saccular function was evaluated by cVEMP. In a study, investigating the relationship between SLE and saccular hydrops, cVEMP has been performed in thirty patients and P1-N1 latencies were shown to be prolonged [20]. In another study, twenty patients with SLE underwent cVEMP testing and P1-N1 latencies were seen to be significantly prolonged [21]. However, no evidence of vestibular system has been found in both studies. Relationships between disease duration and latency of cVEMP have not been investigated in these studies.

In our study, when P1 and N1 latencies were compared between forty-four SLE patients and forty control subjects, P1 and N1 latencies of the left and right ears of the SLE patients were found to be significantly longer than the control group (p <0.05). In addition, 26 (59%) SLE patients with vertigo had significantly longer P1 and N1 latency values than SLE patients without vertigo. Also, there was a significant relationship between vertigo and disease duration (p <0.05).

In another study, electronystagmography (ENG) has been performed in SLE patients and abnormal findings have been found to be significantly higher than healthy subjects [18]. Another study confirmed the presence of abnormalities in the vestibular system via videonystagmography (VNG) and dynamic posturography in pediatric patients with SLE [16].

In a histopathological study, type I hair cells of the cristas in the three semicircular canals, saccular macula and utricular macula have been observed to be affected and the mean density of type I cells was lower in the SLE group when compared to the control group. However, type II hair cells were found to be unaffected. The intensity of type I and type II hair cells has not been associated with the duration of SLE [9]. In a study by Sone et al. [22], the temporal bone of the patients with SLE has been investigated using histopathologic methods and loss of spiral ganglion cells, loss of hair cells in varying degrees and atrophy in stria vascularis have been shown. Also, cochlear hydrops and stenosis in endolymphatic duct have been observed in seven cases. When the SLE group was compared with the control group, it has been observed that a significant amount of peripheral type vestibular pathology is present in the SLE group.

Regarding this information, we aimed to evaluate the saccular function causing balance disorder by performing cVEMP in patients with SLE and to investigate the effect of duration of the disease on vestibular system. Previous histopathological studies performed with VNG and dynamic posturography have shown that the vestibular system is affected. In our study, it was found that saccular dysfunction was more and latencies were prolonged in patients with SLE who underwent cVEMP test. We showed that as the duration of the disease increased, latencies were prolonged in cVEMP. The results revealed that the frequency of vertigo was higher as the disease duration increased. The most important limitation of this study is the low number of cases and the fact that the vestibular test battery has not been used in which the entire vestibular system is evaluated. However, there are only two studies in literature on cVEMP testing in patients with SLE and the relationship between SLE, duration of the disease and vestibular system and their effect on latencies have not been evaluated. This is a different aspect of our study.

Conclusion

As a result, it was found that saccular dysfunction was more and latencies were prolonged in patients with SLE who underwent cVEMP test. We showed that as the duration of the disease increased, latencies were prolonged in cVEMP. The results revealed that the frequency of vertigo was higher as the disease duration increased. it should be kept in mind that vestibular system findings may occur in patients with SLE and we think that evaluation of vestibular system should be performed at certain intervals.

Acknowledgement

None.

Conflict of Interest

No conflict of interest.

References

- Schroeder JO, Euler HH (1997) Recognition and management of systemic lupus erythematosus. Drugs 54: 422-434.

- Kastanioudakis I, Ziavra N, Voulgari PV (2002) Ear involvement in systemic lupus erythematosus patients: a comparative study. J Laryngol Otol 116: 103-107.

- Sperling NM, Tehrani K, Liebling A (1998) Aural symptoms and hearing loss in patients with lupus. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 118: 762-765.

- Yu C, Gershwin ME, Chang C (2014) Diagnostic criteria for systemic lupus erythematosus: a critical review. J Autoimmun 48-49.

- Batuecas-Caletrio A, del Pino-Montes J, Cordero-Civantos C (2013) Hearing and vestibular disorders in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. Lupus 22: 437-442.

- Compadretti GC, Brandolini C, Tasca I (2005) Sudden sensorineural hearing loss in lupus erythematosus associated with antiphospholipid syndrome: case report and review. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol 114: 214-218.

- Gomides AP, do Rosario EJ, Borges HM (2007) Sensorineural dysacusis in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. Lupus 16: 987-990.

- Maciaszczyk K, Durko T, Waszczykowska E (2011) Auditory function in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. Auris Nasus Larynx 38: 26-32.

- Kariya S, Hizli O, Kaya S, Hizli P, Nishizaki K, et al. (2015) Histopathologic findings in peripheral vestibular system from patients with systemic lupus erythematosus: A Human Temporal Bone Study. Otol Neurotol 36: 1702-1707.

- Petri M, Purvey S, Frang H, Magder L (2012) Predictors of organ damage in systemic lupus erythematosus: The Hopkins’ Lupus Cohort. Arthritis Rheum 2: 4021-4028.

- Schlauch RS, Nelson P (2009) Puretone Evaluation. In: JackKatz (Edt,). The Handbook of Clinical Audiology, (6th Edn,). Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, USA.

- Mok CC, Lau CS (2003) Pathogenesis of systemic lupus erythematosus. J Clin Pathol 56: 481-490.

- McCabe BF (1979) Autoimmune sensorineural hearing loss. Ann Otol Rihinol Laryngol 88: 585-589.

- Solares CA, Hughes GB, Tuohy VK (2000) Autoimmune sensorineural hearing loss: an immunologic perspective. J Laryngol Otol 114: 101-107.

- Biesecker G, Katz S, Koffler D (1981) Renal localization of the membrane attack complex in systemic lupus erythematosus nephritis. J ExpMed 154: 1779-1794.

- Gad GI, Abdelateef H (2014) Function of the audio vestibular system in children with systemic lupus erythematosus. Curr Allergy Asthma Rep 14: 446.

- Karabulut H, Dagli M, Ates A, Karaaslan Y (2010) Results for audiology and distortion product and transient evoked otoacoustic emissions in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. J Laryngol Otol 124: 137-140.

- Karataş E, Onat A, Durucu C (2007) Audio vestibular disorders in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 136: 82-86.

- Gazquez I, Soto-Varela A, Aran I (2011) High prevalence of systemic autoimmune diseases in patients with Meniere’s disease. PLoS One 6: e26759.

- Baki A, Cirik AD, Pehlivan O, Yildiz M (2018) Vestibular Evoked Myogenic Potential Responses in Patients. Haydarpasa Numune Med J 58(3): 142-145.

- Roghayeh F, Fahimeh H, Maassoumeh A, Shohreh J, Mahmood (2013) Vestibular evoked myogenic potentials in patients with inactive stage of systemic lupus erythematosus. Audiol 22(2): 63-72.

- Sone M, Schachern PA, Paparella MM (1999) Study of systemic lupus erythematosus in temporal bones. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol 108: 338-344.

-

Tuba Turkman. Evaluation of Saccular Function with cVEMP In Patients with Systemic Lupus Erythematosus. On J Otolaryngol Rhinol. 3(3): 2020. OJOR.MS.ID.000565.

-

Erythematosus, Hearing loss, Tinnitus, Vestibular disorders, Autoimmune disease, Otologic symptoms, Otorhinolaryngology, Audiometry, Cochlear hydrops, Ear damage, Vascular thrombosis.

-

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.