Research Article

Research Article

A Clinical Evaluation of Adaptive Hearing Aid Compression: Exploring its Impact on the Word Recognition Abilities of Spanish Pediatric Hearing Aid Users

Silvia N Breuning1, María Eugenia Prieto1, María Ángela Silva1, Mónica A Jeremías1, Patricia Bernáldez1 and Dave Gordey2*

1Department of Otolaryngology, Hospital for Pediatrics SAMIC Prof Dr Juan P Garrahan, Buenos Aires, Argentina

2Centre for Applied Audiology Research, Oticon A/S, Denmark

Dave Gordey, Director of Pediatric Audiology and Research, Centre for Applied Audiology Research, Oticon A/S, Smorum, Denmark.

Received Date: April 23, 2020; Published Date: May 05, 2020

Abstract

Background: For today’s children with sensorineural hearing loss, speech understanding with their hearing technology is critical. Most pediatric hearing instruments are based on traditional Wide Dynamic Range Compression (WDRC) processing. Unfortunately, this technology has its limitations in dynamic listening environments. A new adaptive compression strategy, with floating linear gain has been developed for hearing aids and shows promise to improve listening for children with hearing loss.

Methods: This clinical evaluation compared within subject performance of twenty children with bilateral sensorineural hearing loss who spoke Spanish and wore hearing-aid technology with WDRC and adaptive compression. Questionnaires recorded parent/caregiver perspectives on their child’s auditory performance with the adaptive compression hearing aid technology.

Results: Speech understanding in quiet and in background noise was better for most children who used adaptive compression. Parent and caregiver questionnaire responses supported these findings.

Conclusion: A new adaptive compression strategy shows promise to improve the listening experiences of Spanish speaking children with hearing loss.

Keywords: Adaptive compression, WDRC, Children, Speech recognition, Hearing aid

Introduction

hearing care professionals, we want children with hearing loss to have the best access to sound in their daily environments. This means their amplification must provide good audibility for speech in quiet, and in complex, noisy environments. Traditional pediatric hearing instruments have utilized Wide Dynamic Range Compression (WDRC) hearing aid processing for the management of soft, average, and loud sounds. This was considered important as young children with hearing loss may not have the ability to adjust their hearing aids and control for sounds that may become uncomfortably loud [1]. Using fixed attack and release times, WDRC can manage a broad range of input levels to the hearing aids. Unfortunately, there are limitations with WDRC. Slow acting WDRC may not provide access to quiet sounds, when followed by those that are loud; while fast acting WDRC may cause distortion, giving speech an unnatural quality and the listener perceives the sounds as “noisy” [2].

Adaptive compression is a new hearing aid processing strategy where different time constants are applied based on the degree to which the sound input changes. When the sound input change is small, a very slow time constant is applied, and the signal is processed in a linear manner [3]. If the change in input is large and abrupt, the time constants of WDRC compression will be used to quickly enable loudness protection and provide audibility of soft sounds [4, 5]. Researchers have compared WDRC and adaptive compression in English speaking adults and children with hearing loss. A study at Arizona State University found that hearing aids with adaptive compression provided better speech understanding in complex listening environments than those with WDRC [6]. In this report, we explore how adaptive compression and WDRC hearing aid processing effect the word recognition abilities of Spanish-speaking, pediatric, hearing-aid users.

Methods

Twenty children, ten male and ten female, with bilateral moderately-severe sensorineural hearing loss, aged eight to sixteen years of age, with typical cognitive development, who used hearing aids in both ears and spoke Spanish as their primary language, participated in this clinical evaluation at the Garrahan Children’s Hospital. The participants and their parents who receive their audiologic care at the Garrahan Children’s Hospital were invited to volunteer for this project. Children were assessed over two clinic visits; the first visit they wore their own hearing aids with WDRC processing technology, and the second visit they wore new hearing aids with adaptive compression. An acclimatization period of six weeks was used to allow the participants time to adjust to wearing different hearing aids. Recorded Spanish bi-syllabic word lists were used to measure children‘s speech understanding abilities in quiet and background noise with each set of hearing aids. Parents completed a questionnaire with ten items and used a five-point Likert scale to rate their child’s listening abilities at home with the WDRC and adaptive compression hearing technology.

Results

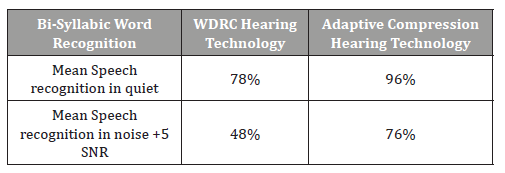

Eighteen of the twenty participants demonstrated better speech understanding in quiet and noise with hearing aid technology with adaptive compression than with WDRC. In quiet, a mean speech recognition score of 78% correct was recorded for WDRC and 96% correct for adaptive compression. In noise, with a +5 signal to noise ratio (SNR), a mean speech recognition score of 48% correct was recorded for WDRC and 76% correct for adaptive compression (Table 1).

Table 1: Speech recognition in quiet and noise; WDRC and adaptive compression hearing technology.

Results from the questionnaire indicated that 80% of the parents noted improvements in their child’s listening abilities with the adaptive compression technology compared to WDRC. Comments from parents indicated that the use of adaptive compression in their hearing aids provided benefits above speech understanding. Improvements in their child’s balance, their child’s own voice quality and increased confidence when participating in sports activities were noted.

Discussion

The listening environments of children with hearing loss are dynamic, busy, and noisy [7]. Good speech understanding in the classroom and school are critical to a child’s learning [8]. The aim of this clinical investigation was to investigate how Spanish speaking children with hearing loss may benefit from adaptive compression compared to traditional WDRC. Results indicated that adaptive compression provided better speech recognition in noise for Spanish-speaking, pediatric hearing-aid users. This supports previous studies that have shown adaptive compression improves speech understanding in noise for both children and adults who are English speaking [6]. For Spanish speaking children with hearing loss, the selection of hearing processing strategies should be considered as important when selecting amplification for children with hearing loss. Future research could build on this clinical investigation and develop a study that is double-blind, withinsubject, and repeated measure design.

Conclusion

Our clinical investigation found that adaptive compression provided better speech recognition in quiet and in noise than WDRC for Spanish-speaking, pediatric hearing-aid users. Their improved auditory performance was observed by most of their parents and/ or caregivers.

Acknowledgement

The authors of this clinical investigation have been given written informed consent by the parents and caregivers of the participants to publish these findings. Hearing aids for this study were donated by Audisonic Argentina. All authors contributed in the writing of this project.

Conflict of Interest

No conflict of interest.

References

- Jenstad LM, Souza PE (2005) Quantifying the effect of compression hearing aid release time on speech acoustics and intelligibility. J Speech Lang Hear Res 48(3): 651-667.

- Arehart KH, Kates JM, Anderson MC (2010) Effects of noise, nonlinear processing, and linear filtering on perceived speech quality. Ear Hear31(3): 420-436.

- Behrens T, Nilsson MJ (2013) How Audiology Has Guided the Development of Oticon’s Latest Release-Alta. Oticon Whitepaper.

- Schum D, Sockalingam R (2010) A new approach to nonlinear signal processing. The Hearing Review 17(7): 24-32.

- Simonsen C, Behrens T (2009) A new compression strategy based on a guided level estimator. Hearing Review16(13): 26-31.

- Pittman AL, Pederson AJ, Rash MA (2014) Effects of fast, slow, and adaptive amplitude compression on children’s and adults’ perception of meaningful acoustic information. J Am Acad Audiol25(9): 834-847.

- Crukley J, Scollie S, Parsa V (2011) An exploration of non-quiet listening at school. Journal of Educational Audiology17(1): 23-35.

- Lewis DE, Valente DL, Spalding JL (2015) Effect of minimal/mild hearing loss on children’s speech understanding in a simulated classroom. Ear Hear36(1): 136-144.

-

Silvia NB, María Eugenia P, María Ángela S, Mónica AJ, Patricia B, Dave G. A Clinical Evaluation of Adaptive Hearing Aid Compression: Exploring its Impact on the Word Recognition Abilities of Spanish Pediatric Hearing Aid Users. On J Otolaryngol & Rhinol. 2(4): 2020. OJOR. MS.ID.000542.

-

Mixed tumor, Apocrine origin, Nasal sill, Chondroid Syringoma, Pleomorphic adenoma, Spontaneous bleeding, Cuboidal cells, Sebaceous gland, Neurofibroma.

-

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.