Research Article

Research Article

Prevalence and Pattern of Self-Medication Among Healthcare Professionals in A Tertiary Hospital in South-South Nigeria

Obodo Precious Morris, Owonaro A Peter*, Suleiman Ismail Ayinla, Obodo Daniel Ugochukwu, Osain Henry Prince and Timipre Okeroghene Aghogho

Department of Clinical Pharmacy and Pharmacy Practice, Faculty of Pharmacy, Niger Delta University, Wilberforce Island, Bayelsa State, Nigeria

Owonaro A Peter, Department of Clinical Pharmacy and Pharmacy Practice, Faculty of Pharmacy, Niger Delta University, Wilberforce Island, Bayelsa State, Nigeria.

Received Date:April 04, 2025; Published Date:April 11, 2025

Abstract

Self-medication is a growing global concern, particularly among healthcare professionals who have easy access to medications. While self-medication can provide quick relief for minor ailments, its misuse to drug resistance, adverse effects, and ethical concerns. The study aimed to assess the prevalence and pattern of self-medication among healthcare professionals at a tertiary hospital in South-South Nigeria. A descriptive cross-sectional study was conducted among 285 healthcare professionals, including medical doctors, nurses, and pharmacists. Data on self-medication practices, common medications used, and associated factors were collected using a structured questionnaire. Data from questionnaires were coded and entered directly into Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) version 24.0 software, which was used for data cleaning and analysis. Descriptive and inferential statistics were used for analysis. The study revealed that there was a high prevalence (79.6%) of self-medication among respondents, with antimalaria (80.6%), analgesics (74.4%), and antibiotics (47.6%) being the most commonly used drugs. The primary reasons for self-medication included familiarity with treatment options, the need for quick relief, and the need to save time. Notably, professional experience and cadre influenced self-medication patterns. Self-medication is widespread among healthcare professionals in the study setting. While it is often seen as a time-saving measure, the risks associated with the improper use cannot be ignored. Hospital management should implement awareness campaigns and policies to regulate self-medication practices among healthcare workers.

Keywords:Self-medication; Healthcare professionals, Prevalence

Introduction

Self-medication is a global problem, with prevalence ranging from 11.7% to 92% [1]. These variations between developing and developed nations are due to differences in cultural and socioeconomic factors, as well as variations in healthcare systems, including reimbursement, regulations, healthcare accessibility, and medication-dispensation policies [2]. However, the prevalence of self-medication is higher, particularly in developing nations and in regions where obtaining prescription medications without a proper prescription is common, including lax in enforcement of pharmacy regulations by established guidelines Al-Qahtani, et al. (2022) [3]. Furthermore, a systematic review and meta-analysis of the population-based analysis conducted by Sisay, et al. (2018) [4] showed that self-medication was mainly practiced by healthcare professionals.

Self-medication is a common healthcare practice worldwide, especially among healthcare practice worldwide, especially among healthcare professionals who have direct access to medications. The World Health Organization (WHO) defines self-medication as the use of drugs to treat self-diagnosed disorders or symptoms or intermittent or continuous use of a prescribed drug for chronic or recurrent diseases or symptoms [5]. Responsible self-medication can be used to prevent and treat ailments that do not need medical consultation or oversight, save time and money that could have been spent on visiting healthcare facilities, and sometimes save lives in acute conditions. On the other hand, wrong self-medication might be associated with harmful consequences like drug resistance, drug dependence, drug interactions, potential delays in accurate diagnosis and treatment of serious health issues, and undesirable pharmaceutical effects [6, 7].

The type of medications used for self-medication and the patterns of self-medication are diverse and influenced by various factors. Analgesics and antimicrobials have been consistently reported as the most common medications used for self-medication [8, 9]. Additionally, antipyretics, antihistamines, and antacids have also been identified as frequently used self-medications, as well as anti-malaria in the tropics [8, 10,11].

Also, Araia, et al. (2019) [12] stated that multiple studies on self-medication across different nations indicated a tendency for individuals to engage in self-medication primarily for ailments such as headaches, abdominal discomfort, fever, pneumonia, sore throats, cramps, eye infections, cold, gastrointestinal issues, and urinary tract infections.

The choice of drugs used for self-medication among healthcare professionals often mirrors those used by the general population and may also include medications that may be more readily available within the healthcare settings. It may also indicate the prevalence of certain health conditions in specific regions. Also, differences in healthcare systems and regulations lead to variations in the type of medications used for self-medication among healthcare professionals across different geographic locations. Some commonly self-medicated medications identified in research studies in different geographic locations, such as the Northeast, South, and Southwest Nigeria, were analgesics, antimalarials, and antibiotics [11, 13, 14]. This was also in consonance with studies in Ghana and India [11, 15].

The implications of self-medication extend beyond the personal realm, potentially influencing patient care, professional ethics, and the overall efficacy of healthcare delivery [16, 17].

Research has also shown that medical knowledge and experience, as well as accessibility to medications, amongst other factors, have been associated with self-medication practices, which has established a level of self-reliance among healthcare professionals. However, this self-reliance can lead to a false sense of security, resulting in the misuse of medications, especially antibiotics, contributing to the growing problem of antimicrobial resistance [17].

Objectives of the Study

The study aimed to

1. Determine the prevalence of self-medication among

healthcare professionals at a tertiary hospital.

2. Identify the most commonly self-medicated drugs and

their indications.

3. Analyze demographic and professional factors influencing

self-medication.

Research Methodology

Study site

This study was carried out in a tertiary hospital, Yenagoa, Bayelsa State, south-south, Nigeria.

Study design

A descriptive cross-sectional design was used in this study.

Sampling technique

A purposive sampling technique was used to select study participants.

Data Collection

A structured questionnaire prepared in the English Language was used as a research tool. The research instrument was certified by the supervisor after a pilot study before the formal distribution to the respondents in the study area.

Data Analysis

Data from questionnaires were coded and entered directly into Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) version 24.0 software. Descriptive statistics such as frequency, percentages, and mean values were used to summarize the data and further expressed in tables and charts. Inferential statistics, including Chi-square tests, were applied to determine associations between certain factors and self-medication practice.

Ethical Issues

Ethical approval was obtained from the Research and Ethics Committee of Federal Medical Centre, Yenagoa, Bayelsa State. Informed consent was obtained from all participants before administering the questionnaire.

Results

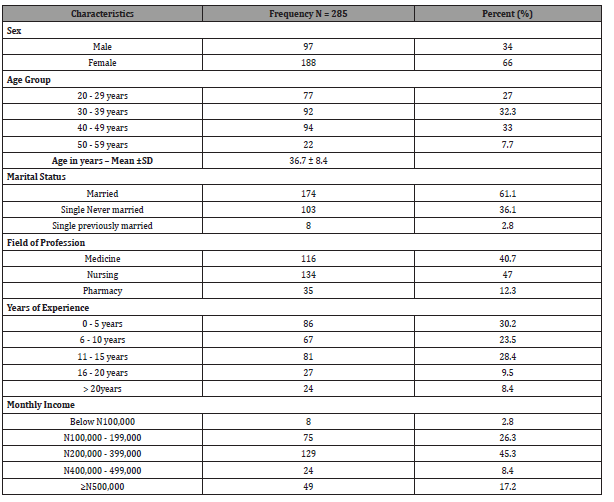

Sociodemographic characteristics of participants

From the results obtained, a total of 285 healthcare professionals participated in the study; 188(66%) were females, while 97(34%). The mean age was 36.7 years (SD±8.4), with the majority in the 40-49 years group (33%). The participants were made up of 134 (47%) Nurses, 116(40.7%) medical doctors, and 35(12.3%) Pharmacists. Eighty-six (30.2%), sixty-seven (23.5%) and eighty-one participants (28.4%), have spent 0-5 years, 6-10 years and 11-15 years respectively as years of experience among healthcare participants in the study as shown in (Table 1).

Table 1:Sociodemographic characteristics of healthcare professionals.

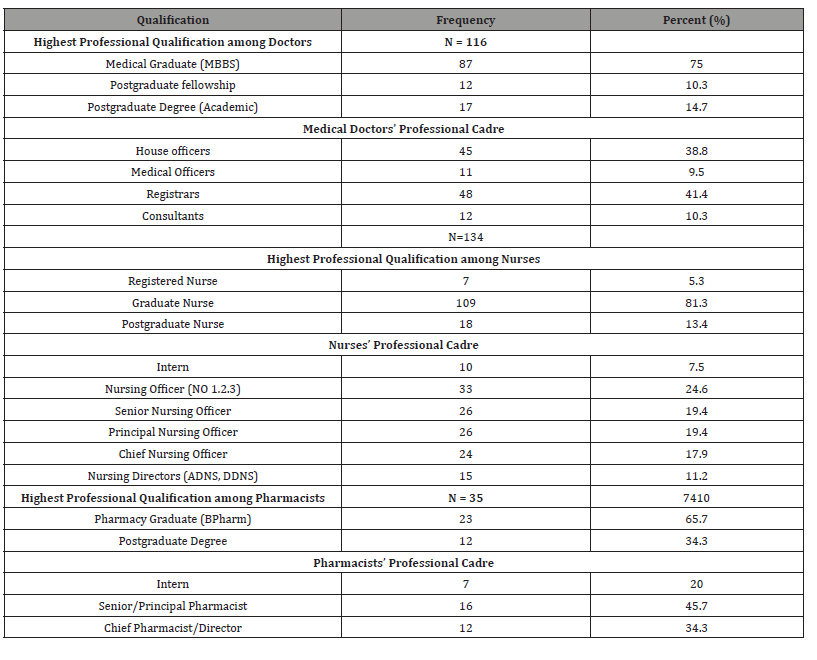

Professional qualification and Cadres among healthcare workers who participated in the study

Table 2:Professional Qualification and Cadres Among Healthcare professionals.

No - Nursing Officer; ADNS - Assistant Director Nursing Services; DDNS- Deputy Director Nursing Services

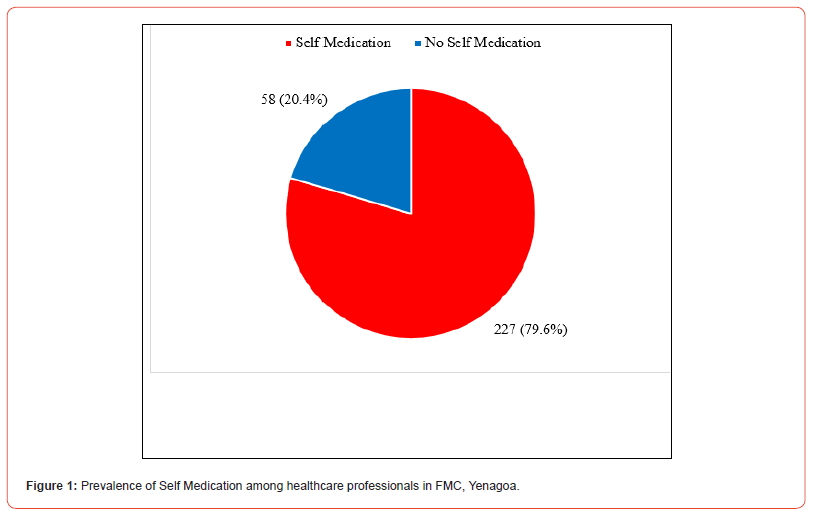

The prevalence of self-medication among healthcare professionals

About 4 in every 5 participants were involved in self-medication, giving a prevalence of 79.6% for self-medication among healthcare professionals in this study, as shown in Figure 1.

The commonly used self-medicated medications among healthcare professionals

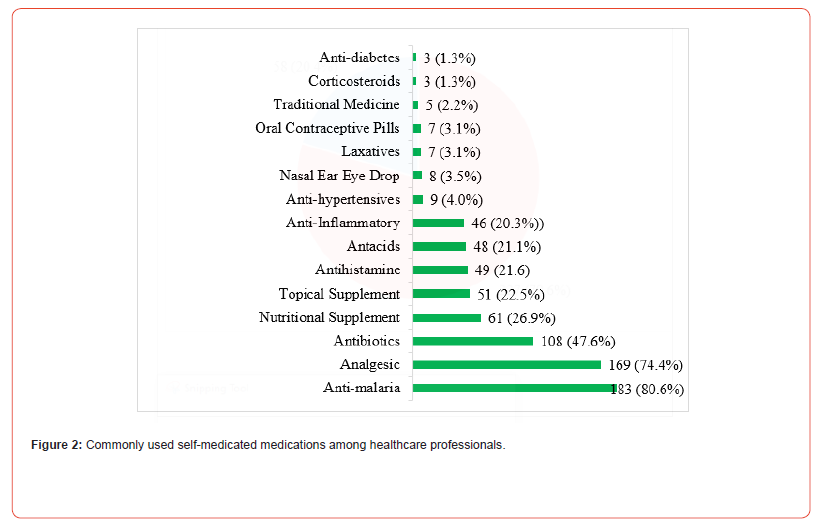

Figure 2 shows that anti-malaria (80.6%), Analgesics (74.4%) and antibiotics (47.6%) were the most commonly used selfmedicated medication among healthcare professionals in FMC Yenagoa.

Common sources of drugs used for self-medication

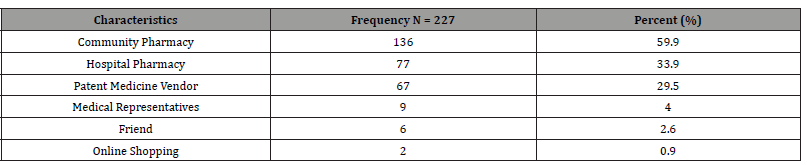

Table 3 shows that the community pharmacy (59.9%) was the most common source for getting drugs for self-medication.

Sources of dose regimens for self-medication among healthcare professionals

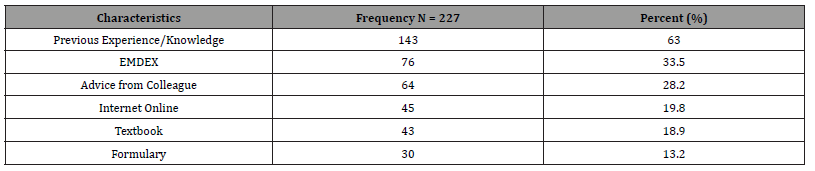

Table 4 shows that most health professionals who self-medicate (63.0%) relied on previous experience/knowledge for the dose regimen of drugs used when self-medicating. Essential Medical Index (EMDEX; 33.5%) and advice from colleagues (28.2%) were other means of determining dose

Table 3:Sources of the drugs used for self-medication among healthcare professionals in FMC, Yenagoa.

Table 4:Sources of dose regimens for self-medication among healthcare professionals.

Indications for self-medication

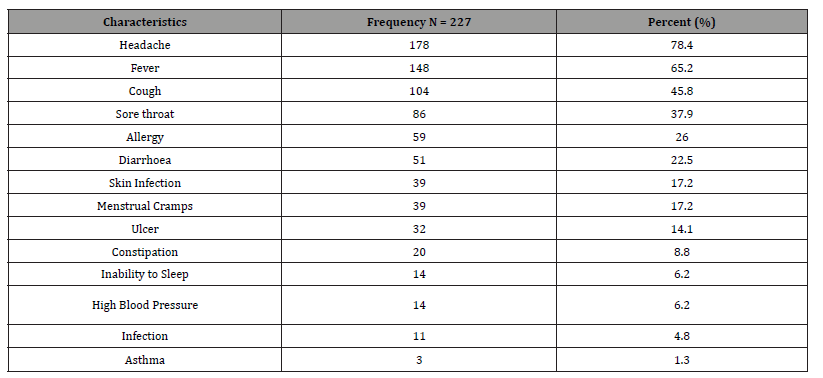

Table 5 shows that one in seventy-eight healthcare professionals (78.4%) self-medicate because of a headache (Table 4.6). Other indications for self-medication include fever (65.2%), cough (45.8%), and sore throat (37.9%), amongst others.

Table 5:Indication for Self-medication among healthcare professionals.

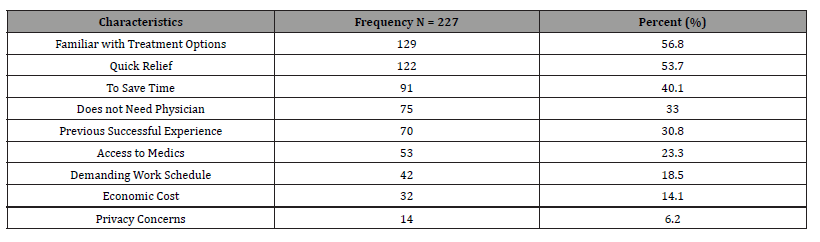

Reasons for self-medication practices among Health care professionals

Table 6 shows that the most common reason for practicing self-medication among healthcare providers is familiarity with treatment options for different ailments (56.8%). Other reasons were for quick relief of their conditions (53.7%) and to save time (40.1%).

Table 6:Reasons for practicing self-medication among healthcare professionals.

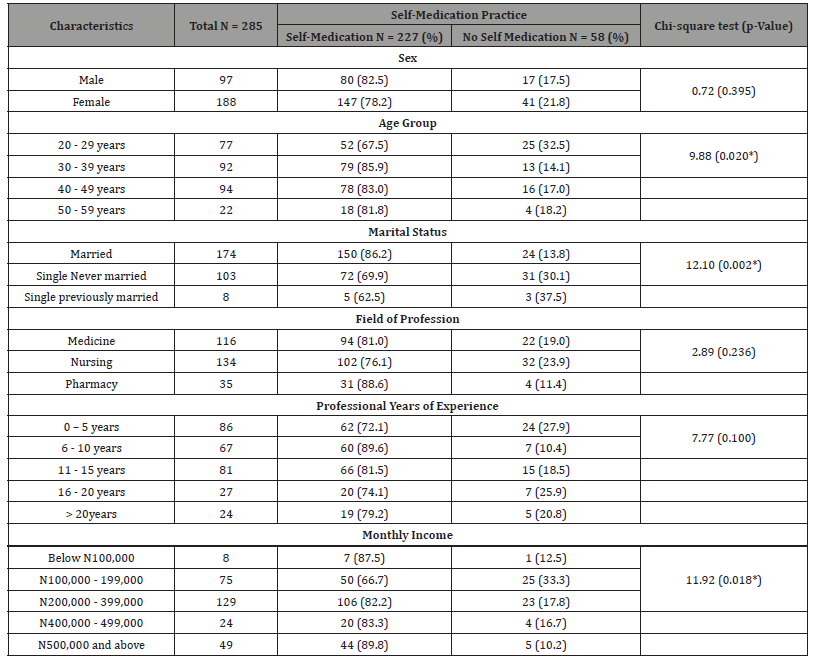

Factors influencing Self-medication

Table 7 shows that age (p=0.02), marital status (0.002), and level of monthly income were significantly associated with selfmedication. Whereas gender, professional field, and years of experience were not significantly associated with self-medication (p>0.05).

Table 7:Association between Sociodemographic characteristics and practice of self-medication among healthcare professionals.

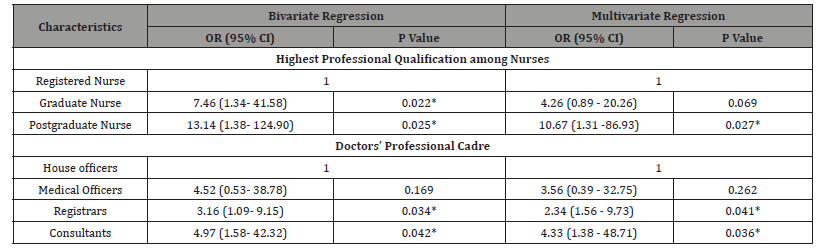

Independent determinants of self-medication

Table 8 shows that the independent determinants of selfmedication practice among healthcare professionals are highest professional qualification among nurses, current professional cadre among doctors and pharmacist.

Table 8:Determinants of self-medication among healthcare professionals in FMC, Yenagoa.

Discussion

There was a total of 285 participants in this study, with females constituting two-thirds of the respondents (66%), while 97(34.0%) were males. This trend might reflect broader gender distribution in healthcare professions, particularly in fields like nursing, which often have a higher proportion of women. Findings from this study revealed a high prevalence (79.6%) of self-medication among healthcare professionals at the Federal Medical Centre Yenagoa. This figure aligns with previous studies carried out by Afolabi, et al. 2010 [18] in Ondo state, south-west, Nigeria, were 73% of health workers in a particular teaching hospital practiced self-medication, also, in a different study in the same South-west region, 52.1% of health workers self-medicated [14]. Furthermore, in a study carried out by Jabbo, et al. (2023) [11] on the prevalence and pattern of self-medication among healthcare workers in a tertiary hospital in North East, Nigeria, there was a high prevalence of 84.6%. This was also in consonance with findings by Tobin, et al. (2020) [13], where the prevalence was 89.3%. The high prevalence observed in this study may be attributed to healthcare professionals’ easy access to medications, medical knowledge, and confidence in self-diagnosis.

The study revealed that the most commonly self-medicated drugs were antimalarials (80.6%), analgesics (74.4%), and antibiotics (47.6%). This is similar to findings by Tobin, et al. (2020) [13] as well as other studies in Nigeria Jabbo, et al. (2023) [11] & Babatunde, et al. (2016) [14] and in consonance with studies in Ghana and India Sajith, et al. (2017) [15], showing high self-medication rates among professionals for similar category of medications. These studies highlight the frequent use of these medications among healthcare professionals, likely due to their frequent encounters with malaria, pain, and infections in their professional practice.

The widespread use of antimalarials and analgesics may be explained by Nigeria’s high malaria burden and the frequent occurrence of body pain and headaches due to work-related stress. The use of antibiotics without a prescription (47.6%) raises concerns about antimicrobial resistance, which is a growing global health threat [19].

Other medications, such as nutritional supplements and topical medications, were moderately used (26.9% and 22.5%, respectively), indicating concerns about general health and skin conditions. Antacids, antihistamines, anti-inflammatories, and antihypertensives show similar moderate use, suggesting these are common self-treatment options for minor ailments or chronic conditions among health care workers. Less frequently used medications include nasal/ear/eye drops, laxatives, and corticosteroids, which reflect more specialized needs or less frequent conditions among the healthcare professionals. From this study, conditions/indications for which healthcare professionals self-medicate include: Headache (78.9%), fever and chills (65.2%), cough and cold (45.8%), and sore throat (37.9%). This is similar to a study by Mohammed, et al. (2021) [20] in which headache was also a common indication for the practice of self-medication among healthcare professionals

This study found significant associations between selfmedication and age (p=0.020), marital status (p0.002), and income level (p=0.018). More than 80% of participants above 30 years selfmedicate, whereas only 67.5% of those between 20 and 29 years self-medicate. This is in tandem with the findings from Tobin, et al. (2020) [13] but in contrast with findings from Fekadu, et al. (2021) [21] in western Ethiopia, where those within the age group of 20- 29 years were more likely to practice self-medication than those ≥ 40 years of age. This contrast could be due to differences in the sociodemographic characteristics of healthcare professionals, sample size, sampling technique, and study area.

Also, those who were married self-medicated more than the unmarried participants in this study, which is similar to findings in Babatunde, et al. (2016) [14]. This similarity could be that married individuals may have more responsibilities and stress, leading to a higher self-medication rate as a coping mechanism. Additionally, they might self-medicate to maintain their health and also fulfill their familial and professional roles. From this study, higher income earners self-medicated more. This may be because higher income likely provides better access to medications and a greater ability to purchase them without financial strain, contributing to higher self-medication rates.

On the other hand, professional field, years of experience, and gender were not significantly associated with self-medication (p>0.05), suggesting that self-medication is a widespread behaviour across all groups.

The majority of respondents obtained their self-medicated drugs from community pharmacies (59.9%), hospital pharmacies (33.9%), and patent medicine vendors (29.5%). While Sources of dose regimens for self-medication among healthcare professionals in FMC, Yenagoa (table 3) were majorly from previous experiences/ knowledge (63%) gotten from using the drugs, EMDEX (33.5%) and advice from colleagues (28.2%). A possible explanation is that healthcare professionals often rely on their prior experience and knowledge gained through education and practice. Adverse drug reactions following self-medication in this study were abdominal pain, itching, and rashes.

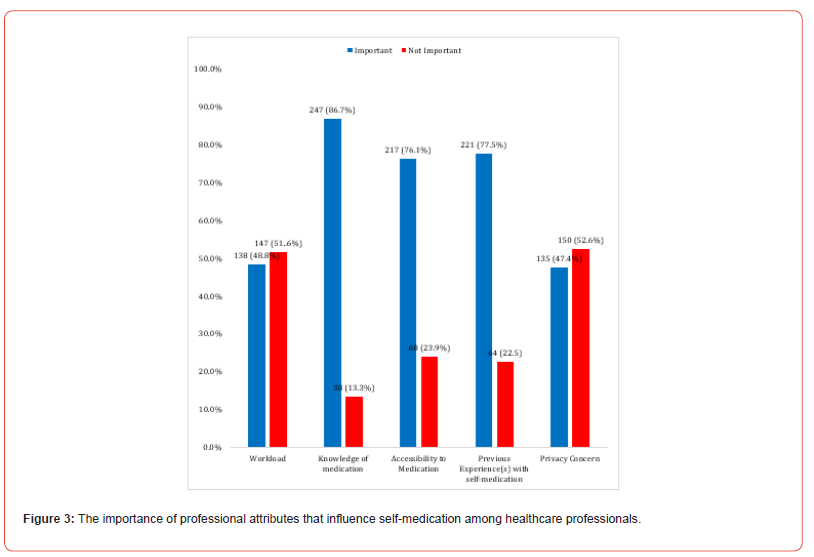

Important professional attributes that influence selfmedication among healthcare professionals in this study (Figure 3) were knowledge of medication (86.7%), previous experience(s) with self-medication (77.5%), and accessibility to medication (76.1%). However, privacy concerns (5.6%) and workload (51.6%) were not important factors that could influence self-medication practice among healthcare professionals in this study. These findings are similar to the study by Jabbo, et al. (2023) [11], which identified familiarity with treatment options and easy access to medication as common reasons for self-medication among health workers, with confidentiality being the least common reason. These factors highlight the role of educational background, professional environment, and personal experience in shaping self-medication practices.

However, to ascertain independent determinants of self selfmedication practices in this study, multivariate regression was carried out, and the result showed that highest professional qualification among nurses, current professional cadre among doctors and pharmacist, were significantly associated with selfmedication practice among health care professionals.

Nurses with postgraduate degrees were found to be ten times more likely to self-medicate (aOR = 10.67; p-0.027) than their colleagues who were registered nurses. This may be because nurses with higher qualifications possess advanced medical knowledge and clinical skills, which may increase their confidence in diagnosing and treating their health issues. Also, nurses with higher qualifications are more likely to have access to a wider range of medical resources, including medications, facilitating selfmedication. However, in a study by Abdelwahed, et al. (2023) [22], a higher level of education was not significantly associated with the practice of self-medication in the multivariate regression analysis. This contrast may be because the study was carried out among a general population and not among healthcare professionals only.

Consultants (aOR = 4.33; p-0.036) and Registrars (aOR = 2.34; p-0.041) had statistically significant higher odds of self-medication than house officers. Also, the likelihood that a senior/principal pharmacist (aOR = 8.31; p-0.035) and a chief pharmacist/Director (aOR = 3.43; p-0.014) will self-medicate was significantly higher than an intern self-medicating (Table 8). The results from this study show that professional cadres among doctors and pharmacists have a strong influence on self-medication practice. This may be due to their advanced clinical experience, in-depth knowledge of medication, and greater autonomy in decision-making. Senior doctors (registrars and consultants) and pharmacists (senior/ principal and chief pharmacists/directors) possess extensive expertise and are accustomed to making independent medical decisions, fostering confidence in managing their health. Additionally, their roles often provide easier access to medications and create an environment where self-reliance and self-treatment are normalized. Also, the World Health Organization (WHO) has acknowledged that responsible self-medication can serve as a valuable approach for improving access to healthcare, particularly in areas where resources are scarce, emphasizing that individuals should be empowered to manage their health conditions, provided they do so with the necessary knowledge and precautions [23]. From this study, healthcare professionals self-medicate due to their basic knowledge about medicines, irrespective of their field of profession [24].

Conclusion

This study highlights the high prevalence of self-medication among healthcare professionals, particularly with antimalarials, analgesics, and antibiotics. While self-medication is commonly practiced for minor ailments, the inappropriate use of antibiotics raises serious concerns about antimicrobial resistance. Addressing this issue requires a combination of regulatory measures, hospital policies, and awareness programs to promote rational drug use among healthcare professionals.

Recommendation

The findings here suggest that educational programs should be designed to emphasize the risks of self-medication, especially among healthcare workers, to promote responsible medication use.

Acknowledgement

There was no conflict of interest among the authors. The researchers appreciated the statistician, participants, and researchers for their time.

Conflict of Interest

No Conflict of Interest..

References

- Rathod P, Sharma S, Ukey U, Sonpimpale B, Ughade S, et al. (2023) Prevalence, Pattern and reasons for self-medication: A Community Based Cross-Sectional Study from Central India. Cureus 15(1): e33917.

- Osemene KP, Lamikanra A (2012) A study of the prevalence of self-medication practice among university students in South-Western Nigeria. Tropical Journal of Pharmaceutical Resources 11(4): 683-689.

- Al-Qahtani AM, Shaikh IA, Shaikh MAK, Mannasaheb BA, Al-Qahtani FS (2022) Prevalence, Perception, Practice, and Attitude towards Self-medication Among Undergraduate Medical Students of Najran University, Saudi-Arabia: A cross-sectional study. Risk management and Healthcare Policy 15: 257-276.

- Sisay M, Mengistu G, Edessa D (harmacol Toxicol 12018) Epidemiology of self-medication in Ethiopia: a systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. BMC P 9(1): 56-68.

- Karthik RC, Dharshanram R, Menaka V, Diwakar PMK (2018) Knowledge, Attitude and Practice of Self-Medication among Patients Visiting a Dental Hospital in Chennais. A Cross-Sectional Study. International Journal of Recent Scientific Research 9(10): 29395-29398.

- Bennadi D (2013) Self-Medication: A Current Challenge. J Basic Clin Pharm 5(1): 19-23.

- Ghasemyani S, Benis MR, Hosseinifurd H (2022) Global, WHO Regional and Continental Prevalence of Self-Medication from 2000 to 2018: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Annals of Public Health 1-18.

- Ayalew M (2017) Self-medication practice in ethiopia: a systematic review. Patient Prefer and Adherence 11: 401-413.

- Anaba E, Cole‐Adeife M, Oaku R (2021) Prevalence, pattern, source of drug information, and reasons for self‐medication among dermatology patients. Dermatologic Therapy 34: e14756-e14762.

- Girish O, Divya HM, Prabhakaran S, PP V, Koppad R, et al. (2013) A cross-sectional study on self-medication pattern among medical students at kannur, north kerala. Journal of Evolution of Medical and Dental Sciences 2(45): 8693-8700.

- Jabbo MA, Osho FT, Habib AA, Abdullah KM, Abba U (2023) Prevalence and pattern of self-medication among healthcare workers in a tertiary hospital in Northeast Nigeria. Cognizance Journal of Multidisciplinary Studies 3(7): 588- 594.

- Araia ZZ, Gebregziabher NK, Mesfun AB (2019) Self-medication practice and associated factors among students of Asmara College of Health Sciences, Eritrea: A cross-sectional study. J Pharm Policy Pract 12(1): 3-12.

- Tobin EA, Erhazele J, Okonofua M, Nnadi C, Nmema EE, et al. (2020) Self-medication among healthcare workers in a tertiary hospital in Southern Nigeria: Knowledge, attitude and practices. Medical Journal of Indonesia 29: 403-409.

- Babatunde OA, Fadare JO, Ojo OJ, Durowade KA, Atoyebi OA, et al. (2016) Self-medication among Health workers in a tertiary institution in South-West Nigeria. Pan Afr Med J 24: 312-320.

- Sajith M, Suresh SM, Roy NT, Pawar A (2017) Self-medication practices among healthcare professional students in a tertiary care hospital, Pune. The Open Public Health Journal 10(1): 63-68.

- Shafie M, Eyasu M, Muzeryin K, Worku Y, Martin-Aragon S (2018) Prevalence and determinants of self-medication practices among selected households in addis ababa community. Plos One 13: e0194122.

- Simegn W, Dagnew B, Dagne H (2020) Self-medication practice and associated factors among health professionals at the university of Gondar comprehensive specialist hospital: a cross-sectional study. Infect Drug Resist 13: 2539-2546.

- Afolabi, AO, Akinmoladun, VI, Adebose, IJ, Elekwachi, G (2010) Self-medication profile of dental patients in Ondo State, Nigeria. Niger J Med 19(1): 96-103.

- Pentareddy M, Vedula P, Roopa B, Chandra L, Amarendar S (2017) Comparison of pattern of self-medication among urban and rural population of Telangana state, India. International Journal of Basic & Clinica Pharmacology 6(11): 2723-2726.

- Mohammed SA, Tsega G, Itailu AD (2021) Self-medication practice and associated factors among health care professionals at Debre Markos Comprehensive Specialist Hospital, Northwest Ethopia. Drug Healthc Patient Saf 13: 19-28.

- Fekadu G, Dugassa D, Negera GZ (2020) Self-medication practices and associated factors among healthcare professionals in selected hospitals of western Ethiopia. Patient Prefer Adherence 14: 353-361.

- Abdelwahed AE, Abd-elkader MM, Mahfouz A (2023) Prevalence and influencing factors of self-medication during the COVID-19 pandemic in the Arab region: a multinational cross-sectional study BMC Public Health 23 180.

- Agrawal R, Sharma S, Jaiswal M, Sharma R, Ali S (2019) Evaluation of knowledge, attitude and practice of self-medication among second year undergraduate students in bastar region: a questionnaire-based study. International Journal of Basic & Clinical Pharmacology 8(4): 817-820.

- Sholabi WA, Ajamu AT, Adisa R (2021) Prevalence, Knowledge and Perception of Self-medication Practice Among Undergraduate Health care Students. Journal of Pharmaceutical Policy and Practice 14(1): 49-60.

-

Obodo Precious Morris, Owonaro A Peter*, Suleiman Ismail Ayinla, Obodo Daniel Ugochukwu, Osain Henry Prince and Timipre Okeroghene Aghogho. Prevalence and Pattern of Self-Medication Among Healthcare Professionals in A Tertiary Hospital in South-South Nigeria. On J Otolaryngol & Rhinol. 7(3): 2025. OJOR.MS.ID.000665.

-

Cough, Headache, Abdominal discomfort, Fever, Pneumonia, Sore throats, Cold, Fever, Stress, Medical resources

-

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.