Research Article

Research Article

A Systematic Review of Sucralfate Role in Post Adenotonsillectomy Pain Control

Mohamed EL-Amin1*, Shahed Abdelmahmoud2, Reem Abdelwahab3 and Vijay Pothula4

1Edge Hill University, Liverpool, UK

2James Cook University Hospital in Middlesbrough, UK

3Ribat University Hospital, Khartoum, Sudan

4ENT Department, The Royal Albert Edward Infirmary, Wigan, Greater Manchester, UK

Mohamed EL-Amin, Edge Hill University, Liverpool, UK.

Received Date: February 16, 2022; Published Date: April 01, 2022

Abstract

Background: Tonsillectomy is the procedure needed to remove the tonsils, usually due to recurrent tonsillitis. There is a specific criterion for children and adults to be eligible for tonsillectomy. Generally, these are episodes of severe sore throat that are preventing people from functioning normally. Most of the postoperative analgesia practice involves the use of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and opioids analgesia. Still, their use can increase the risk of postoperative nausea and vomiting, bleeding, altered alertness and respiratory depression. Also, NSAIDs can increase the risk of nephrotoxicity with dehydration. Anti-emetics should be used if the patient complains of post-op nausea and vomiting.

Objectives: What is the role of sucralfate in post-tonsillectomy pain control and how can it be used to improve post-tonsillectomy pain management?

Search methods: This review was a result of extensive search among all available source of kinds of literature. Databases were assessed between March 2018 till September 2018 including all searching engines in relevance to health Specialized Register, CENTRAL, MEDLINE, EMBASE, CINAHL and PsycINFO and not missing the grey literature and general internet searching websites. Also, we accessed all the possible libraries and local hospital department to seek more information about the topic of the mentioned review.

Selection criteria: All identified randomised controlled trials discussed the role of sucralfate were included in this systematic review in relevance to post adenotonsillectomy pain control. Risk of bias monitored carefully.

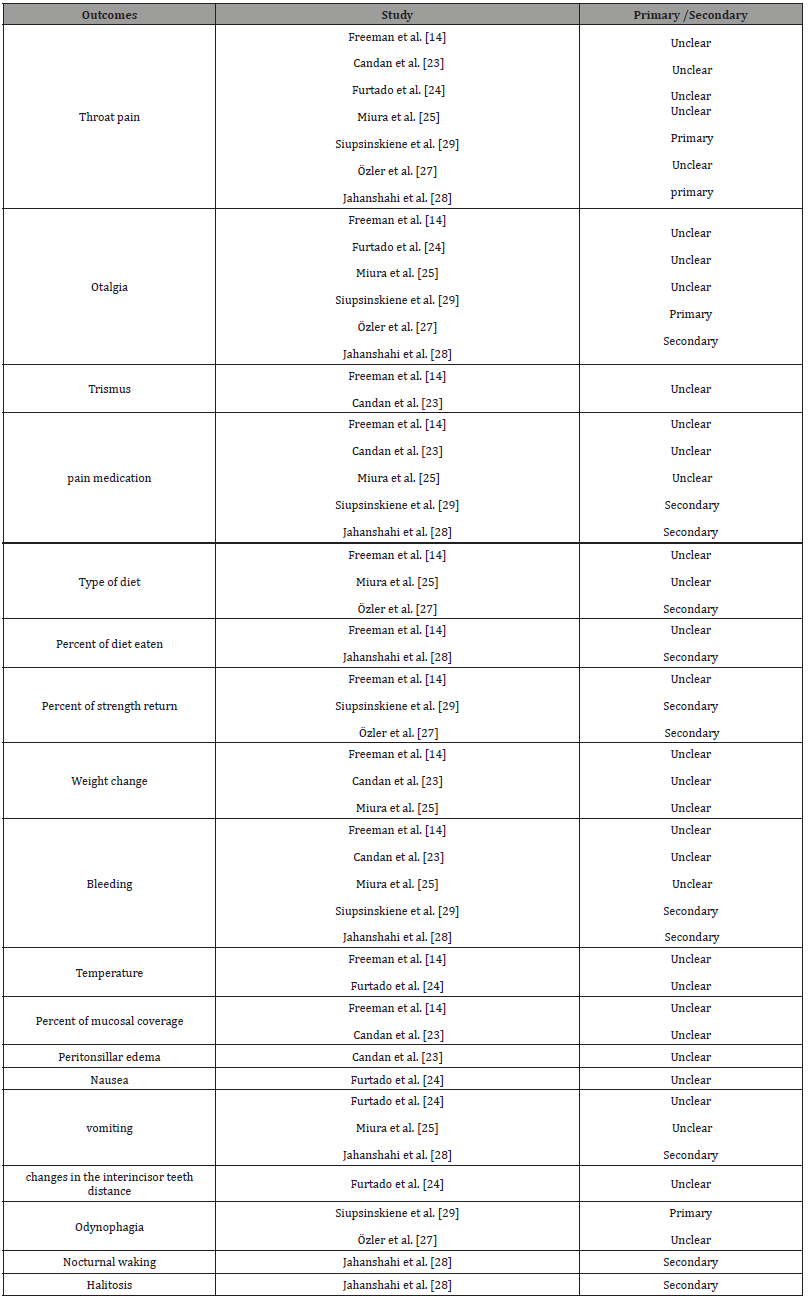

Data collection and analysis: Two reviews managed to collect and assess the data. PRISMA platform, which is an evidence-based minimum set of items for reporting in systematic reviews and meta-analyses, was followed carefully in reporting all the data in relevance to the mentioned topic. Data were collected from different parts of the word with a lot of variations in practice and heterogenicity. It is recommended by this review to run a multicentre randomised controlled trial with adjusted protocol to help in having one unity of data analysis to help in future in the meta-analysis. Sucralfate is not yet included as part of post adenotonsillectomy postoperative guidelines in pain management. This review established a future potential for sucralfate to be used as regular in everyday practice as part of postoperative pain management in patients going for adenotonsillectomy. Main results: The search identified seven trials (455 patients) that they were eligible to join the study. This review identified 18 outcomes were pool all from the papers. We concluded that any outcome was discussed by five or more papers to be included as Primary outcomes: Throat pain, otalgia, pain medication, bleeding, and vomiting. Vomiting was also included to measure the side effects of sucralfate which can cause nausea and vomiting.

All of the outcomes analysed in the study were: throat pain, otalgia, trismus, pain medication, type of diet, percentage of diet eaten, Percent of strength return, weight change, bleeding, temperature, ratio of mucosal coverage, per-tonsillar oedema, nausea, vomiting, changes in the teeth distance, odynophagia, nocturnal waking Halitosis. Most of the studies showed results of statistical significance of p-value <0.05 or less as early from day two up to day five to show a significant improvement. Only one study which was conducted under local anaesthesia showed insignificant result statistically of sucralfate of Value greater than 0.05.

Conclusion: Sucralfate application is beneficial adjuvant therapy to help in improving post adenotonsillectomy pain control. It helped patients’ post-op sore throat to enhance faster, and patients were able to go back to their baseline after the operation quicker. Also, it helped to a great extent to reduce the intercity of ear pain, and there is evidence in which it helps reducing the risks of post-tonsillectomy bleeding.

Background

Description of the condition

Tonsillectomy is the procedure needed to remove the tonsils, usually due to recurrent tonsillitis. There is a specific criterion for children and adults to be eligible for tonsillectomy. Generally, these are episode of severe sore throat that are preventing people from functioning normally. Specifically, if these were exceeded by seven in a year, five or more in two years or 3 episodes in 3 years [1]. There are also other medical conditions in which tonsillectomy has specific indications like in tumours, snoring, sleep apnoea and obesity. Adenoidectomy is a procedure commonly done among childhood period because the adenoid tissue will shrink to become more of small ruminant tissue during adulthood and advance age [1].

In the UK, according to The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guidelines, when the specific criteria are met, then a referral will be made from the primary health care to the secondary care under the regulations of the commission groups with the accepted funding process [1]. Thereafter, the patient will be listed for tonsillectomy. It is usually a day case in children and adults unless other comorbidities exist [1].

Cold steel dissection is the most common procedure used for removal of the tonsils. It separates it from its bed by blunt dissection after making a limited incision on the tonsil’s mucosa [2]. Bleeding control and haemostasis usually achieved through local pressure with a swab or pieces of gauze, and ligation of bleeding vessels with or without the use of diathermy [3]. In the 1990s, Coblation was introduced as a kind of electrosurgery with less heating effect on the tissues than the diathermy [3]. It utilises the advantages of the radiofrequency current, which is produced by a bipolar probe in a medium of sodium chloride. It is recognised for its less heating and pain effect after surgery. It carries better rates of pain control but a higher risk of primary and secondary bleeding than cold steel dissection [3].

Over the last recent years, laser technology has become more involved in Ear, Nose, and throat (ENT) practice along with CO2 and Potassium titanyl phosphate (KTP) laser are both used in tonsillectomies [4]. There are three main approaches: laser vaporisation, laser-assisted serial, and complete removal by laser tonsillectomy. All techniques have a high rate of bleeding than the cold steel dissection; with reported higher pain scores which often worsens gradually and can last up to 2 weeks [4].

In the UK tonsillectomy using ultrasonic scalpel had been approved for practice by the NICE guidelines [4] if proper training had been delivered to surgeons. Because it is not commonly practiced in the National Health Service (NHS) hospitals, clear considerations should be implemented regarding the clinical governance needed for establishing such a service, audit and monitor their practice to develop such a service. Tonsillectomy using ultrasonic scalpel works through the ultrasonic energy vibrations [4]. A disposable scalpel will be used with the advantage of cutting and coagulating at the same time to secure hemostasis. Vibration produces a temperature that varies between 55 to 100 C leading to less tissue damage than diathermy or laser devices. Pain scores have been re regarded as the same compared to the other methods. The bleeding rate was found to be less in other ways considering the primary bleeding (bleeding within the first 24 hours), but rates are variable regarding the secondary bleeding [4].

Tonsillectomy and adenoidectomy are both very common among the procedures which are part of every ENT theatre list, especially in children. Taking into consideration its simple principles as a procedure, the pain which may result from tonsils’ removal can be very severe and can take up to 7 days till it starts to improve (Ericsson, et al. 2015). The complete resolution might take up to 2-3 weeks until patients begin to function normally in a good state of health. Thus, children, oral intake and recovery time will be delayed leading to a long postoperative hospital stay, bearing in mind the fact that it is usually a day case surgery unless associated with complications [5].

Postoperative pain control

Most of the postoperative analgesia practice involves the use of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and opioids analgesia. Still, their use can increase the risk of postoperative nausea and vomiting, bleeding, altered alertness and respiratory depression [6]. Also, NSAIDs can increase the risk of nephrotoxicity with dehydration. Anti-emetics should be used if the patient complains of post-op nausea and vomiting [6].

Objectives

The question I want to find an answer for it is “What is the best medical intervention which can be practiced up to the most recent evidence to help in improving post-tonsillectomy pain management” Considering at the same time all the other factors of cost, training, research, and availability of the service to be an everyday practice under the umbrella of the NHS. Different studies had been conducted to improve the quality of post-tonsillectomy and adenoidectomy pain management, including using local anesthetic medication to be infiltrated in the tonsils area. Th e us e of the local an aesthesia found to have similar good control of pain post adenoidectomy and tonsillectomy when injected locally into the wound area [5, 7, 8]. But it is complex technical, and experience issues with the fact most on local analgesia infiltration works only for a short duration deemed this approach as not significant. Furthermore, studies result varied a lot in their recommendations between supporting and refusing this approach [5].

Different approaches had been tried i n both the medical and surgical fields. Fibrin glue was found of insignificance in pain control. Fusafungine also had been tried and results again were variable between supporters and those who had insignificant effects [9]. Local steroids injection [10], but all showed deferent variations in evidence of symptoms improvement and control with further consideration to the risk of bleeding and other systematics side effects of the steroid. However, no single treatment is claimed to be superior to others in controlling post-tonsillectomy pain. A recent meta-analysis showed a compelling, significant result in the reduction of postoperative pain score with honey [11]. But still, a multimodal approach in controlling the pain is usually suggested [12].

How the intervention might lead to desirable outcomes

Sucralfate action is based on the salts of aluminum ability to formulate a protective layer over the ulcer site. It is due to the biochemical advantages of sucralfate; it does not dissolve in water, and it forms a strong bond with the mucoproteins in the exposed muscle of mucosal layers. It is powerful in acidic PH [13]. Nevertheless, it does not lose its adhesive characteristics in a normal PH like in the mouth or duodenum. That will help the mucosal to generate and cover the muscle layers at the base of the ulcer [13].

Why trying to do this review

That raised the question of why not using sucralfate in tonsillectomies pain control as the pain is mainly related to the inflammation, irritation of nerves and muscle spasms at the bed of the tonsillar fossa. Therefore, the pain will be persistent for almost 14 days in some cause until the tonsillar fossa mucosal surface heal and cover the operation site completely [14]. If we think about the tonsillectomies operation: removal will result in two large ulcers at the back to the oral cavity which will take almost two weeks to heal.

Methods

Search methods and strategy

Data had been extracted with a wide range of word search terminology and usage of the thesaurus to make sure we gathered all the possible published research in relevance to post-tonsillectomy pain control. Words used were tonsillectomy, adenoidectomy, tonsillitis, adenoids, pain, management, sucralfate, analgesia, post, randomised, trial. This source of data had been collected from well-structured up to date website; MEDLINE, EMBASE, NHS Evidence, PubMed. Also, it was extending to include search in Google Scholar, and another grey source of data like local publications which is not part of the universal source for data and local medical libraries Universities database had also been included. Cochrane database included considering the ENT group at the same time to compare all the relevant previous systematic reviews and trials done before. This strategy was recommended by The Centre for Reviews and Dissemination [15].

Data Collection and Analysis

Selection of studies

The two reviewers of the systematic review run a separate data search which ends up in 2 databanks. Then the selection of the studies was made through the voting process. If 2 agreed the paper would be added, and rejected documents were unable to meet the voting process. For the ones with partial agreement further assessment was conducted by gathering more details.

Assessment of risk of bias and quality in included studies

In this, a systematic review of all the RCT included with was evaluated and critically appraised according to the criteria established by the Centre for Reviews and Dissemination published by the University of York January 2008 [15]. It highlighted the main steps, topics which is essential to be covered in a systematic review while assessing randomised control trials. Also, the Preferred Reporting for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) methodology was used when reporting the systematic evaluation of sucralfate role in pain control post tonsillectomies. The PRISMA contains 27 items through which critical appraisal of systematic reviews structure was carried out by a checklist including the title, abstract, introduction, methods, results, discussion, and funding of the study [16]. All the randomised control trials included in the systematic review had been critically appraised through the checklist of Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP) [17], and by the guidelines of the Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine (CEBM) (CEBM, 2014) [18].

This study mainly evaluated quantitative data; therefore, confidence intervals of 95% confidence had been the reflection of an actual effect [19]. It was supposed to help us in analysing the impact of sucralfate and comment on the effectiveness of the methods used in each study [19]. But because of wide heterogeneity in the data meta-analysis was do not.

Dealing with difficult data to be obtained

Some of the data found to be missed from the papers final reporting. Efforts made to contact the authors for more clarification and to include the studies, but no success was achieved out of those trials. Because of that, these studies were excluded from the review. That will be mentioned in the exclusion criteria of papers.

Data synthesis

All the information included in this study was collected by another researcher and me. For all the studies considered for this study, the data had been collected will consist of; the source associated with its ID citation and contact details. Regarding the eligibility, all reason for exclusion was mentioned. Recording of study design, duration, sequence generation, allocation sequence, and concealment, blinding and bias were all discussed with the effect of drop out. Furthermore, authors had been investigated regarding the date of their studies, country, setting, diagnostic criteria, age, sex, comorbidity, socioeconomic status, and ethnicity (PRISMA 2017) [16].

In all studies, sucralfate was the main intervention group. All details about the dose, mode of administration and records of its effects had been analysed according to the scales pain utilized to evaluate the intensity of pain. Variations between the studies were considered including duration, time, and the dose of administration of sucralfate. Also, the interventions affected the outcomes of each study according to the way it had been administered. Analysis of the results was included in the form of sample size, the number of participants with proper measurement of effect P value and confidence interval (PRISMA, 2017) [16].

Then the assessment of the risk of bias was conducted, and that will be included: section, performance, detection, attrition, and reporting bias [20]. Therefore, each study risks were categorized into the low, high, or unclear risk of bias.

After gathering all the relevant results, factors affecting the publication bias were analysed. In the review done by Hopewell in 2008; it concluded that studies with positive results were more likely to be published than negative results with odds of publication of 4 times greater than others if the statistical significance of OR = 3.90, 95% 2.68-5.68).

Results

This systematic review was conducted electronically using Review Manager 5.3 software (RevMan) and the software Mendeley. It is recommended by the Cochrane website as part of the software needed for proper analysis of such reviews and results gathering [21].

Reporting of all the outcomes was monitored according to the PICO criteria and the statistical significance of the result was check and documented [21].

The effect of the sample size and all the other factors affected the conduction of all the studies included. Tables were formulated by the end including all the essential characteristics of each study; author-date; country, study design, inclusion and exclusion criteria, interventions are done, comparisons were conducted, loss of follow up and outcomes. As part of the quality assessment, the strength, limitations, and weakness of each individual study in the analyses was mentioned if it was documented in the view [21].

Ethical approval will not be needed. There will be no direct contact with any patients. All data will be extracted from the previous studies and analysed electronically. Then, all outcomes will be discussed to address the review question and the possible benefits of using sucralfate in post-tonsillectomy pain control. Each study will be challenged for its ethical approval and if the authors managed to seek proper consent regionally or internationally according to each study conditions.

This study will be registered with the international database for systematic reviews of the Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO). The Centre developed it for Reviews and Dissemination (CRD) University of York. It is funded by the National Institute for Health Research of UK (NIHR) [20]. It was launched in February 2011, and since that time, it had been on continues upgrade and continued contribution to the international database [22]. This was the first systematic review considering the use of sucralfate in post-tonsillectomy pain control. I believe publishing THE results of this is study will add more to our understanding of sucralfate role and measure are in place to guard against any publication bias like citation, duplication, location, language, and outcomes biases.

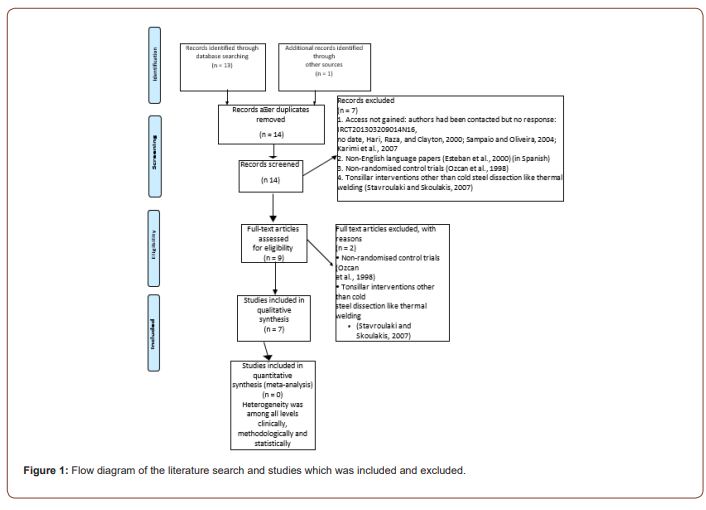

This is the first systematic review of the sucralfate role in posttonsillectomy pain control. I hope it will expand our understating about the post-tonsillectomy pain mechanisms and help us to improve our practice in postoperative pain management and control. Description of included studies (Figure 1).

Study Design and Setting

In total seven studies included in this systematic review. These studies took places in different part of the world. It exhibited diversity in its population but at the same time that was a source of heterogeneity [14, 23-27]. The power calculation was only done in two studies [25, 28]. Also, it was mentioned on Siupsinskiene, et al. [29] but the actual process not documented.

Participants

Particepents were from diffident age groups, and they had there only characterised which reflected by their demographics.

The total number of patients who took part in this study were

455 patients.

1. Two studies were conducted in adults: Fifty adult patients

were included in (Freeman, Markwell and Markwell, 1992).

Forty-three adults volunteers were part of [23].

2. Three studies in children groups: Sixty-nighen children aged

3 to 12 years were involved in the study, which was done by

[24]. Then it was then until the study conducted by [25] with

Eighty-two children of both sexes between four and 12 years.

Then the study conducted by [26] which included 101 children

aged 6 to 12 years.

3. Two studies included children and adults: Then it was [29]

who studies sucralfate in fifty patients (age 6 to 58). The last

study which was included had participants of 60 volunteer

over eight years [28].

Interventions and comparisons

Studies included all discussed the role of sucralfate in posttonsillectomy symptoms management. The aim was to find the effective way of administering the drug orally, gargles, irrigation or swallow to act locally on the tonsillar bed area to help to improve post-tonsillectomy pain control and improve the postoperative pain management. It was supposed that it would help mucosal healing as the same principle for the way how sucralfate can act locally on peptic ulcer mucosal lining [29]. Lactulose was the placebo in all the studies whenever possible. Although some studies had only a control group without placebo, some studies added both placebo and control groups together. Others check commented on the outcomes with the effect of antibiotics.

Sucralfate vs placebo

• Freeman, Markwell, and Markwell, 1992: for a total ten days

four times a day. Intervention: 60mls of solution contains 1g sucralfate

Placebo: 60mls of solution contains 1g of lactose

• for the total of 7 days [24]

• Intervention: 60mls of solution contains 1g sucralfate Placebo:

60mls of solution contains 1g of lactose

• (Miura et al., 2009) for five days four times a day

• Intervention: 60mls of solution contains 1g sucralfate Placebo:

60mls of solution contains 1g of lactose

Sucralfate vs control

• for seven days [29]

• Intervention: 60mls of solution contains 1g sucralfate control:

no intervention was done: only randomised to post-op pain killers

• for seven days: [27]

• Intervention: sucralfate

• Control: None

Sucralfate vs placebo vs control/

• Candan, et al. [23] for total five days four times a day Intervention:

50ml of solution contain 1g of sucralfate

Placebo: 50 ml of solution contain lactose 1g of sucralfate Sucralfate

vs placebo vs clindamycin

• Jahanshahi, et al. [28]

Anaesthesia and perioperative peri-operative management Operative

procedures

Cold steel dissection and stitches

• Furtado, et al. [24]

• Miura, et al. [25]

• Jahanshahi, et al. [26]

Cold steel dissection and the snare technique:

• It was the stander procedure used by Freeman, et al. [14], Candan,

et al., [23] ad Özler, et al. [27]

1. cold dissection and electrocautery with or without packing

and stitches [29].

Hemostasis Mechanisms

1. Local pressure and stitching:

• Furtado, et al. [24]

• Miura, et al. [25]

• Özler, et al. [27]

• Jahanshahi, et al. [28]

2. Local pressure, stitching, and electrocautery:

• Freeman, et al. [14] extent of cauterisation was recorded on a

scale of 3 degrees from minimal, moderate to extensive.

• Siupsinskiene, et al. [29] Anaesthesia

1. Local: Not clearly mentioned the type of anaesthetic medication

Candan, et al. [23]

2. General: Inhalation of sevoflurane or by an intravenous induction

with tionembutal then maintained with inhalation of

sevoflurane [24].

Anaesthetic induction room with midazolam 0.5 mg/kg orally was used [25].

Local/general: Most of the patients were in Freeman, et al. in

1992 [14] study were under general anaesthesia with infiltration

of Xylocaine containing epinephrine. Three of the operations performed

on the placebo group were done under local anaesthesia.

3. Others: Ketoprofen using intramuscular injections for the

first two days; then orally for the next five days, they were

when necessary. Children in both groups received 500 mg of

oral paracetamol form all seven days [29].

4. Not clearly mentioned induction of anaesthesia methods: Siupsinskiene,

et al. [29]

Özler, et al. [27] Jahanshahi, et al. [28] Outcomes

All outcomes included in all studies were listed in Table 1, to allow comparison between different studies:

Excluded studies

Studies were excluded according to deferent reasons:

1. Access not gained: authors had been contacted but no response:

IRCT201303209014N16, no date, Hari, et al. [30],

Sampaio and Oliveira [31], Karimi, et al. 2007 [32]

2. None English language papers [33] (in Spanish)

3. Non-randomised control trials (Ozcan, et al., 1998) [27]

4. Tonsillar interventions other than cold steel dissection like

thermal welding [34]

5. (IRCT201303209014N16, no date; Ozcan, et al. [37]; Esteban,

et al. [33], Hari, et al. [30]; Sampaio and Oliveira [31], Karimi,

et al. 2007 [32].

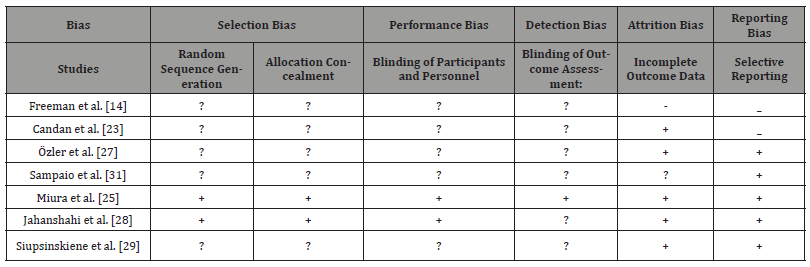

Risk of bias in included studies

Randomization and allocation (selection bias)

The method of sequence generation was unclear in five studies [14, 23, 24, 27, 29]. For only two studies The methods of randomisation were mentioned clearly: randomised blocks [25] and balance block randomisation method [26]. It is essential to be clear about the randomisation methods and explain which type was used. It is not enough just to mention the process. Randomisation can be done through one of these methods: referring to a random number table; using a computer random number generator; coin-tossing; shuffling cards or envelopes; throwing dice; drawing of lots and minimisation. It is recommended by Cochrane to identify the risk of bias, and according to that, it is an unclear risk of bias in the above four papers and low risk of bias in the other two papers [25, 26] (Table 1).

Table 1:All outcomes included in the studies.

Two studies only clearly described a low-risk method of allocation concealment, which was conducted by a pharmacist to avoid the bias of making the clinicians aware of the process [29]. For this reason; this study had followed the category of low risk of bias during the allocation process. In Miura, et al. [25], study a clear inclusive flowchart of all the study phases was formulated with detailed information about the numbers of participated involved.

The other the five studies, there was no clear documentation of the allocation process mentioned and that put these studies in the category of the unclear risk of bias. Low-risk bias in concealing allocation could have been minimised if any of the recommended methods (telephone, web-based and pharmacy-controlled randomisation; sequentially numbered drug containers of identical appearance; sequentially numbered, opaque and sealed envelopes. (Cochrane Methods Bias, 2011) was followed correctly. Methods which can make the process of low risk of bias if followed correctly in conceal allocation: central allocation.

Blinding

Blinding means to make both groups: the intervention and the control/placebo group unaware of the intervention itself [35].

Only one studies out of the seven studies had detailed information about the blinding process, blinding the investigators and patients [25]. It was explained that sucralfate was made similar to the placebo (lactulose) with details about the preparation itself. That put this study in a low risk of performance and detection bias. In regards, to performance and detection bias there was an unclear risk of bias in all the rest of the studies [14, 23, 26, 27, 29, 31]; as blinding was only mentioned as part of describing the study but no exact details were mentioned to explain who were made blind, the intervention or the placebo group. In Jahanshahi, et al. [29], a pharmacist was involved in the area phases, but again no more details were mentioned.

Incomplete outcome data

According to Roshan, et al. [36] it is critical to report all the outcomes’ data that’s including the primary outcomes and the secondary outcomes. Any missed data or incomplete reporting of all data will affect the result of the study. Intention to Treat Analysis is vital to be done to avoid misleading results.

It was mentioned in [14] that nine candidates were eliminated for failure to complete the journal, 5 for lack of follow-up, and one due to the incorrect usage of the test drug. One patient in the placebo group had a delayed haemorrhage requiring cauterisation and was removed from the study. No patients were eliminated for intolerance of the test drug, and no intention to treat analysis was done. That put the study on high-risk category.

On the study carried out by [23] none of the participants were missed during the study time. So, no data was missed [31]. On their paper “Evaluation of early postoperative morbidity in paediatric tonsillectomy with the use of sucralfate,” five patients were excluded because of the lack of follow-up and four because of the incorrect use of the test drug. Two patients had delayed bleeding, requiring a haemostatic suture, and were excluded from the study. No evidence was found about any further analysis and tracking of the effect of the missed data. It is categorised as unclear risk of bias.

In Miura, et al. [25] study only two patients were reported as a drop of the study: in the sucralfate group, one patient was excluded due to high fever, and one patient was excluded because of loss to follow-up. Considering only two patients out of 82 is unlikely that have much effect considering the power calculation, which was done in this study. It was the only power calculation which was mentioned in all the studies. The percentage of loss was calculated as 15 per cent and for minimal involvement of each group of 35 participants. This detailed information will put this study on the low risk of bias group. These power calculations which were done by Minura, et al. [25] was the base for the power calculation for another study which was conducted by Jahanshahi, et al. [28]. He adopted the sample size selection technique to make study groups of a minimal of 35 candidates with anticipation of 5% of sample loss. Out of 110, only nine patients were excluded. On the discussion, it was mentioned that part of the limitation of the study was the sample size as that might have let to small sampling error. All these analyses had put this study in the low risk of bias concerning incomplete data of outcome recording.

In the study ‘’ Use of Topical Sucralfate in the Management of Postoperative Pain After Tonsillectomy which was conducted by [27] no data was reported as missed data, and all participants completed the study in both intervention and control group. Again, no data was reported as missed or incomplete for the study conducted by Siupsinskiene [29] and all patient of a count of 50 on both groups completed the full duration of the study for seven days. Also noted all outcome measures were recorded. Both studies are of low risk of bias concerning incomplete data recording.

Selective reporting

Study outcomes should be reported in a systematic way with appropriate outcome measures: primary and secondary. They should be written in text with supporting statistical evidence to show the significance of the outcomes measured. In randomised control trials outcomes reporting will be strong statistically when P values are recorded, the mean and the standard deviation are calculated. Also, data analysis of confidence intervals is critical to reflect on comparative and metanalysis of the results; especially when testing drugs or interventions for future use in humans (Reviews, 1992; US Department of Health and Human Services Food and Drug Administration, 2018).

It was concluded that [14] study had a high risk of bias as pain scores were not measured with standard pain scales [14]. It only graded the pain on a scale of 4 levels. Also, there was reporting of some data on graphs without supporting statistical evidence. Secondary outcomes were not reported in full details.

Considering the results and outcomes of Candan, et al. [23], it was built upon non-standardised pain scale, and hence results can’t be taken a statistically significant although P values and standard deviation were recorded. Here the procedure also was done under local anaesthesia, so the postoperative pain was severer than the other studies when the operations were conducted under general anaesthesia. This study was deemed as high-risk of bias study.

In the study which was conducted by [31] a comprehensive data outcomes reporting was done. That included a standardised scale of pain to measure results. Also, all primary and secondary outcomes with P- Values and Standard deviation were recorded. Data also was presented in tables and diagrams. For all these reasons, it was rated as low risk of bias.

The rest four studies were deemed of low risk of bias: all primary and secondary outcomes were reported in a standardised way. Pain measurement and scores were measured in a standardised way with a well-known wide used standard scale of pain: Revised Faces Pain Scale [25, 26], visual analogue scale (VAS) [27, 29].

Other potential sources of bias

The surgical practice of removing tonsil was very variable from place to another. Variations of technique had affected the results of the outcomes. According to this section of analysis factors affecting outcomes were: Types of anaesthesia conducted, measures of pain control, variations of outcomes, variations of outcome measures and duration of follow up. Also, it was noticeable that there were no standardised ways of applying the intervention plus placebo and control groups variations. The demographics of the population were variable. Age groups included were of wide range, and some studies had children and adults at the same time. Scales of monitoring the pain also were very variable; some were standardised, and others were locally adapted scales. These factors will be discussed in the coming sections with more inputs about the interventions and outcomes. In this study a comprehensive analysis for the bias was conducted. Please refer for Table 2 for more generalised view in relation to the bias analysis.

Table 2:Type of bias was found in the included studies.

Discussion of the Results and Outcomes

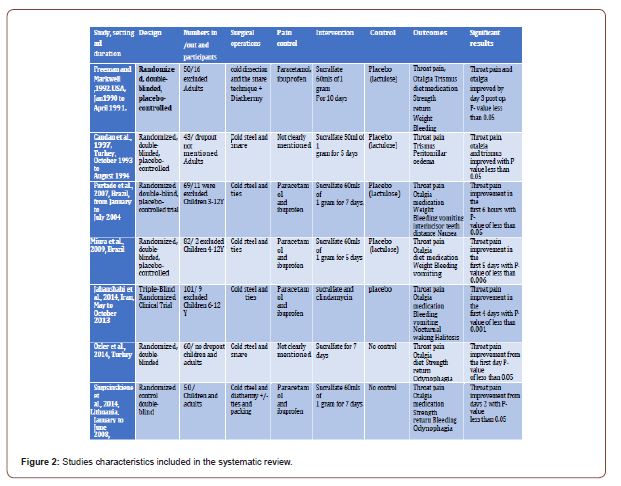

In this section, we discussed the result of all the including papers, according to the authors, as different methods and result were optioned. Please refer to the Figure 2 for a comparable view of the studies and their characteristics.

Sucralfate in Alleviating Post-Tonsillectomy Pain [14]:

Throat pain and otalgia showed significant result mainly by the

3rd day of with P-Value of < 0.05 including.

The use of pain medications posts operatively, and trismus results

showed p < 0.05 by the first day.

Strength and power showed significant improvement in most

of the days. Diet improved after the 5th day irrespective to the type

of diet.

On the other hand, weight, bleeding, temperature, and Percent of mucosal coverage all were of insignificant result statistical result. Exclusion and elimination: 9 patients were eliminated for failure to complete the journal, 5 for lack of follow-up, and one due to the incorrect usage of the test drug. One patient in the placebo group had a delayed haemorrhage requiring cauterisation and was removed from the study. No patients were eliminated for intolerance of the test drug.

Sucralfate in Accelerating Post -Tonsillectomy wound Healing [14].

Throat pain, otalgia, and trismus all show results of P-value more than 0.05 of statistical significance. But it was statistically significant with a P value less than 0.05 in peritonsillar oedema and epithelisation rate. This is the only study which showed statistical insignificance in sucralfate role in post-tonsillectomy pain control. Also, we need to release those operations were done under local anaesthesia. Therefore, sucralfate is not expected to control the pain more than work as a useful adjuvant in pain control (Table 2) (Figure 2).

Exclusion and Elimination:

Evaluation of early postoperative morbidity in paediatric tonsillectomy with the use of sucralfate [24]. Patients in the study group had significantly lower pain scores in the initial six postoperative hours (p < 0.05). The difference between the two groups was not statistically significant for the other periods following the procedure or on the evaluation of the other indices.

Exclusion and elimination:Five patients were excluded because of the lack of follow-up and four because of the incorrect use of the test drug. Two patients had delayed bleeding, requiring a haemostatic suture, and were excluded from the study.

Topical sucralfate in post-adenotonsillectomy analgesia in children:A double-blind randomised clinical trial [25]. Reduction of pain was significant during the five days of treatment when compared to the placebo group with the P value of P < 0.006. On the other hand, all other parament showed no significant difference.

Exclusion and elimination:In the sucralfate group, one patient was excluded due to high fever, and one patient was excluded because of loss to follow-up.

Effect of Topical Sucralfate vs Clindamycin on Post tonsillectomy Pain in Children Aged 6 to 12 Years A Triple-Blind RandomiSed Clinical Trial [29].

Effects of topical sucralfate and clindamycin vs. placebo on postoperative clinical signs and symptoms of a sore throat was statistically significant on the first four days after surgery (P =A .001). However, the result was not of clinical significance for the other parameters.

Exclusion and elimination:11 were ineligible, and six declined to participate.

From the 2nd to 7th postoperative days, patients using topical sucralfate had significantly lower average throat pain, odynophagia and otalgia scores than the control group (p < 0.05).

Exclusion and eliminationnone

Efficacy of sucralfate for the treatment of post-tonsillectomy symptoms [29]. From the 2nd to 7th postoperative days, patients using topical sucralfate had significantly lower average throat pain, odynophagia and otalgia scores than the control group (p < 0.05).

Exclusion and elimination:none

Use of Topical Sucralfate in the Management of Postoperative Pain After Tonsillectomy [27].

Throat pain scores, odynophagia scores, otalgia scores from the first-day post-op and the time through the whole duration of the study were significantly lower than the control group (p<0.05). However, it took a mean return to normal diet and returned to regular daily activity more time but were of statistical significance later p (p=0.0001).

Summary of main results

On pooled data of results, sucralfate showed statistically significant effects of the P-value of 0.05 or less in all parameters measured. Although outcomes measure varies a lot though studies with different population demographics [14, 24, 25, 26, 27,29].

To be mentioned one study showed not much significance of sucralfate in pain control [23].

Conclusion

Implications for practice

In summary, it was an extensive systematic review which showed the possibilities of achieving good pain control after adenotonsillectomy with sucralfate application on the tonsillar bed after removal of the tonsils. The practice was very variable, with papers from different parts of the world. Methods and outcome reporting were inconsistent in terms of the outcomes and the outcomes measures. However, all showed good and encouraging results towards considering sucralfate in post-tonsillectomy pain control. Also, as noted, the side effects of the drug are very minimal and mild in most cases. Consider the simple way of applying sucralfate and its significant results in controlling the post- tonsillectomy pain; more studies are needed with more adjustment of the risks of bias to test is effect and role in post-tonsillectomy pain.

Implications for research

Studies included in this review were of multiple risks of bias clinically, methodological, and statistically. A broad multicentre randomised control trial is needed to get appropriate conclusions and results about the intervention.

Acknowledgement

Special thanks to the library team who helped us to collect all the data needed.

Ethics

All the papers showed ethical approval by it is local authorities. In this systematic review and patient contact not needed. Approval of the study was gain by Edge Hill University ethical committee to conduct the study as part of the March degree with Edge Hill University.

Declarations of Conflict interest

This is the first systematic review in such a topic in relevance to pain control post adenotonsillectomies.

I declare no conflict of interest in regard to this publication.

References

- Rcseng.ac.uk (2016) Commissioning guide: Tonsillectomy.

- The Royal College of Surgeons of England (2004) National Prospective Tonsillectomy Audit FINAL REPORT of an audit carried out in England and Northern Ireland between July 2003 and September 2004. The Royal College of Surgeons of England.

- org.uk (2005) Electrosurgery (Electrosurgery -diatherm diathermy and coblation- for y and coblation) for tonsillectom tonsillectomy.

- org.uk (2006) Tonsillectomy using a laser. The National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE).

- Ericsson E, Brattwall M, Lundeberg S (2015) Swedish guidelines for the treatment of pain in tonsil surgery in pediatric patients up to 18 years. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol 79: 443-450.

- Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network (2010) Management of sore throat and indications for tonsillectomy: a national clinical guideline, Edinburgh: Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network.

- Karaaslan K, Yilmaz F, Gulcu N, Sarpkaya A, Colak C, et al. (2008) The effects of levobupivacaine versus levobupivacaine plus magnesium infiltration on postoperative analgesia and laryngospasm in pediatric tonsillectomy patients. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol 72: 675-681.

- Heiba M, Atef A, Mosleh M, Mohamed R, El-Hamamsy M (2012) Comparison of peritonsillar infiltration of tramadol and lidocaine for the relief of post-tonsillectomy pain. J Laryngol Otol 126: 1138-1141.

- Akbas Y, Pata Y, Unal M, Gorur K, Micozkadioglu D (2004) The effect of fusafungine on postoperative pain and wound healing after pediatric tonsillectomy. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol 68: 1023-1026.

- Steward D, Grisel J, Meinzen-Derr J (2011) Steroids for improving recovery following tonsillectomy in children. Cochrane Database Syst Rev: CD003997.

- Hwang S, Song J, Jeong Y, Lee Y, Kang J (2014) The efficacy of honey for ameliorating pain after tonsillectomy: a meta-analysis. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol 273: 811-818.

- Snidvongs S, Ullrich K, Fletcher D (2013) Management of postoperative pain after tonsillectomy. Ear Nose Throat J 98: 356-361.

- Szabo S, Hollander D (1989) Pathways of gastrointestinal protection and repair: Mechanisms of action of sucralfate. Am J Med 86: 23-31.

- Freeman SB, Markwell JK (1992) Sucralfate in Alleviating Post-Tonsillectomy Pain. Laryngoscope 102: 1242-1246.

- CDC (2008) Systematic Reviews “CRD’s guidance for undertaking reviews in health care. (1st Edn). York: University of York, UK.

- Prisma-statement.org (2017) PRISMA.

- Katrak P, Bialocerkowski A, Massy-Westropp N, Kumar V, Grimmer K (2004) A systematic review of the content of critical appraisal tools. BMC Med Res Methodol 4: 22.

- Critical Appraisal tools - CEBM. CEBM.

- Lewis K (2006) Statistical Power, Sample Sizes, and the Software to Calculate Them Easily. BioScience 56: 607.

- Davies S (2012) The importance of PROSPERO to the National Institute for Health Research. Systematic Reviews 1: 5.

- http://community.cochrane.org/tools/review-production-tools/revman-5/revman-5- download

- Chien P, Khan K, Siassakos D (2012) Registration of systematic reviews: PROSPERO. BJOG: 119: 903-905. [Crossref]

- Candan S, Sapci, Türkmen M, Karavuş A, Akbulut UG (1997) Sucralfate in accelerating post-tonsillectomy y w o u n d healing. Marmara Med J 10: 79-83.

- Sampaio ALL, Pinheiro TG, Furtado PL, Araújo MFS, Olivieira CACP (2007) Evaluation of early postoperative morbidity in pediatric tonsillectomy with the use of sucralfate. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol 71: 645-651.

- Miura MS, Saleh C, de Andrade M, Assmann M, Ayres A, et al. (2009) Topical sucralfate in post-adenotonsillectomy analgesia in children: A double-blind randomised clinical trial. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 141: 322-328.

- Jahanshahi J, Pazira S, Farahani F, Hashemian F, Shokri N, et al. (2014) Effect of Topical Sucralfate vs Clindamycin on Posttonsillectomy Pain in Children Aged 6 to 12 Years A Triple-Blind Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 140: 698-703.

- Özler GS, Arli GS, Akoglu E (2014) Use of Topical Sucralfate in the Management of Postoperative Pain After Tonsillectomy. J Ann Eu Med 2: 17-20.

- Jahanshahi J, Pazira S, Farahani F, Hashemian F, Shokri N, et al. (2014) Effect of Topical Sucralfate vs Clindamycin on Posttonsillectomy Pain in Children Aged 6 to 12 Years. JAMA 140: 698.

- Siupsinskiene N, Žekonienė J, Padervinskis E, Žekonis G, Vaitkus S (2014) Efficacy of sucralfate for the treatment of post-tonsillectomy symptoms. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol 272: 271-278.

- Hari CK, Raza SA, Clayton MI (2000) Pain relieving effect of sucralfate in adult tonsillectomy. Laryngo-Rhino-Otologie 79: S102.

- Sampaio ALL, Oliveira CA (2004) Evaluation of postoperative morbidity in pediatric tonsillectomy with sucralfate. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 131: P275.

- Karimi C, Baradaranfar MH, Mirvakily A, Atighehi S, Vahidy MR (2007) Assessment of the effectiveness of sucralfate in reducing pain of tonsillectomy patients. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol Head Neck 264: S57.

- Esteban F, Soldado L, Delgado M, Barrueco JC, Solanellas J (2000) The usefulness of sucralfate in the postoperative improvement of children’s tonsillectomy. An Otorrinolaringol Ibero Am 27: 393‐404.

- Stavroulaki P, Skoulakis C (2007) Thermal Welding Versus Cold Dissection Tonsillectomy: A Prospective, Randomized, Single-Blind Study in Adult Patients. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol 116: 565-570.

- Boutron I, Estellat C, Guittet L, Dechartres A, Sackett DL, et al. (2006) Methods of blinding in reports of randomised controlled trials assessing pharmacologic treatments: A systematic review. PLoS Med 3: e425.

- Roshan V, Zenda S (2018) Understanding Intention to Treat Analysis and Per Protocol Analysis. J Tumor Med Prev 3: 2-3.

-

Mohamed EL-Amin, Shahed Abdelmahmoud, Reem Abdelwahab, Vijay Pothula. A Systematic Review of Sucralfate Role in Post Adenotonsillectomy Pain Control. On J Otolaryngol & Rhinol. 5(3): 2022. OJOR.MS.ID.000614.

-

Tonsillitis, Tonsillectomy, Tonsil’s mucosa, Cold steel dissection, Ear, Nose, Throat, Anti-inflammatory drugs, Post tonsillectomy pain, Pain control.

-

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.