Research Article

Research Article

Building Environmental Literacy through Holistic Storytelling

Kristiina A Vogt1*, Alexa Schreier1, 2, Alishia Orloff3, Michael E Marchand4, Daniel J Vogt1, Phil Fawcett5, Samantha De Abreu1, Turam Purty5 and Maia Murphy-Williams1

1School of Environmental and Forest Sciences, University of Washington, Seattle, Washington, 98195-2100, USA

2Evans School of Public Policy & Governance, University of Washington, Seattle, Washington, 98195-2100, USA

3School of the Environment, Yale University, New Haven, Connecticut, 06511, USA

4Confederated Tribes of the Colville Reservation, Omak, Washington, 98841, USA

5iSchool, University of Washington, Seattle, Washington, 98105, USA

Kristiina A Vogt, School of Environmental and Forest Sciences, Bloedel Hall, 3715 West Stevens Way NE, University of Washington, Seattle, Washington, USA.

Received Date: July 24, 2021; Published Date: August 19, 2021

Abstract

Today, technology delivers information related to our environment, but not the skills of how to form knowledge and wisdom when too much data is available due to technology. Therefore, many environmental problems persist for decades as researchers explore one narrow aspect of the problem, and do not recognize problem interconnectivities. This fosters environmental illiteracy in the environmental decision process. In contrast, the holistic knowledge-forming process of Indigenous People teach their youth to form holistic knowledge of nature and to realize that their decisions may impact 7 generations of their tribe. This prepares each tribal member to be part of the community-level decision process. Therefore, the concept of STEM science learning should be expanded to include Indigenous STEAM (iSTEAM) to help build environmental literacy.

Keywords:Too much environmental information; Decontextualized management; Indigenous and Local knowledge; Holistic stories; Wisdom deprivation; Indigenous STEAM

Communities as our Source of Knowledge

Environmental problems of our day are treated as a monolith: separated from inherent political, economic, and societal dimensions. We know this because many approaches have been used to solve environmental problems and yet those problems have continued to persist for decades [1,2]. Traditional top-down processes isolate external, decontextualized knowledge to inform internal policy and management practices, which ultimately impact local communities and not the decision-makers. These decisions are based on pre identified solutions which allows decision errors to be propagated throughout the decision process since they are based on framework theories and not local theories that are predictive and refutable [3]. These errors are used to justify biased decisions that benefit only a few and not the local community, even when the decision has the potential to result in an environmental or societal catastrophe. This fundamentally weakens ensuing legal and political frameworks because they do not present the context of interconnected issues and relevant stakeholders impacted by the decisions made for each problem. Frequently the top-down approaches represent the views and values of decision-makers and special interest groups with an economic stake in the solutions. They do not give a voice to indigenous or local people who live close to the land and are the most impacted by these decisions, and who “hold vital ancestral knowledge and expertise on how to adapt, mitigate, and reduce climate and disaster risks” [4]. Who better to collaborate with than the Indigenous people who account for ~6% of the world’s population but “own, occupy, or use a quarter of the world’s surface area, they safeguard 80 percent of the world’s remaining biodiversity” [4]. Most Indigenous groups have preserved global biodiversity sustainably over many centuries, far more than any modern civilization, but are usually only consulted after decisions have already been formalized by management agencies.

This exclusion of communities with local knowledge or those with a different knowledge of a problem is not uncommon when a non-holistic lens is used to assess a complex problem. Taleb [5] wrote “No time in history of humankind have more positions of power been assigned to people who don’t take personal risks.” Most decision-makers do not grow up or live close to the land like indigenous peoples, and rarely experience the negative impacts of their decisions on themselves or on their communities. In contrast, Native Americans have to prioritize their options and reduce the risks of making wrong choices since they depend on their land base for survival. Thus, resource and environmental knowledge populate the center of Indigenous culture as well as their economies. Indigenous economic models prioritize making decisions to first protect the environment, second health, third culture and fourth economic development; sovereignty and cultural resources are also not negotiable if an Indigenous/Tribal Peoples business model is to succeed [6].

These priorities are central to indigenous approaches to resource management and provide a model for reorienting our own approaches to addressing environmental problems. The misalignment of societal values in our knowledge-forming systems is most conveniently observed through recent repudiation of evidence-based science. It was recently published that state and federal governments have been suppressing the inclusion of evidence-based science in decision-making following the 2016 U.S. national elections [7,8]. This regretfully means that evidence-based science is given less consideration in political decision-making today. This deprivation of evidence-based science will ultimately have lasting repercussions for our security, safety, and health [8]. So, evidence-based science must be realigned with public priorities and acknowledge the potential impacts it may have on different communities in order to build trust and address environmental concerns. Science is part of the decision-making process but there are many ways of forming knowledge if the goal is to make environmentally- and socially-just decisions. For example, inclusion of community stakeholders who are most impacted by the problem should be a priority. Fortunately, there are several sources and forms of knowledge that successfully employ these methods with regards to the environment. These models provide a foundation that we can use to build and improve upon our current decision tools.

In the United States, our pursuit of solutions for environmental problems have (d)evolved to be disciplinary focused to form a broader understanding of the natural world. It uses the scientific method to identify predefined solutions that are tested to solve a problem. When Native people interact with scientists, they have to translate their holistic knowledge using the western world scientific method. This requires them to communicate using a reductionistic method of thinking that no longer represents Indigenous ways of forming knowledge [9]. This evolution has prioritized linear evidence-based science and excluded stakeholders at the heart of the issue and the solution resulting in the perpetuation of environmental inequities. Furthermore, these drawn out or neglected environmental problems challenge public engagement, especially in politically contentious and disrespectful circumstances. Thus, we become desensitized and unwilling to participate in the issues that are important to our health and safety. This is not a reality for which we should accept or settle. We have the resources, the capacity, and the decency to acknowledge the value of all voices, and in doing so, to meaningfully impact our future when the appropriate time and investment is committed. These are processes that we need to continually audit and modify as the future presents additional obstacles. Through the right lens, we could achieve holistic resource management and adaptive comprehension for the future that are environmentally, socially, and economically just.

The take-home message we are advocating for is that local communities should be guiding the development of knowledge and co-managing local lands and waters. Environmental problems cannot simply be solved with additional technology. A combination of technology and local expertise is required. The union of technology and societal engagement situates environmental issues at the forefront of our dominant culture and discourse and affirms a plurality of shared experiences. Digital technology in particular is an effective tool in centering local environmental narratives. Cunsolo, et al. [10] showed how digital storytelling is a community-driven methodology that can unite digital media outputs with oral wisdom while also fostering unity among a diverse group of people. They wrote that “digital storytelling is a powerful strategy for engaging individuals who have been historically silenced, marginalized, and/or tokenized. [10]. In fact, storytelling, as part of this tool kit, is how Indigenous People successfully maintain environmental literacy. These knowledge-forming processes are developed at a young age so that indigenous youth can uphold environmental stewardship and connections to the land. While all cultures develop these storytelling skills, modern industrial societies have displaced us from our stories and broken our link to the landscape. These interconnectivities need to be re-established for a society to make holistic environmental decisions [11].

Historically, scientists trained in the scientific method were de facto the gate keepers of acceptable scientific knowledge and facts [12]. Today, this is changing because technological innovations provide massive amounts of data for us to evaluate and utilize. Weingart and Guenther [12] writes how the public trust in the science is being hurt by technologically based popular media that competes with science for people’s attention. Historically, people not trained in the scientific method and knowledgeforming processes were excluded in the decision process despite the importance of their views in the political process. People unable to understand environmental problems in a holistic manner depend on others who they trust to be the gate keepers of acceptable facts to search for solutions. Today technology provides us a tsunami of information at a click of a key on our smart phone or computer [13,14]. People, therefore, need to identify who to trust to represent their viewpoint since they do not have time to research each problem.

Recently, Indigenous voices are contributing significantly to landscape management issues such as the salmon habitat restoration projects which are being successfully implemented by several tribes collaborating on restoring wetland areas for salmon habitat on their customary lands [15]. Also, Citizen Science is providing another important role in the local knowledge-forming process and are trusted by local communities to communicate science in the popular media [12,16]. Using a holistic lens to tell stories about environmental problems would expand the role of local communities as producers of acceptable science knowledge. It would also make it easier to identify errors in the decision process that may result in an environmental disaster. A definition of the problem would identify the viewpoints of people who are excluded because they are not members of the institutional power structure, e.g., Indigenous People. The impacts of excluding key stakeholders who are essential to form solutions to a complex, landscape problem is explored in the next section.

Ineffective Environmental Problem Definition: Northwest Forest Plan Example

For decades, evidence-based science developed by scientists in academia and management agencies provided the scientific evidence and tools to support environmental decision-making processes in the United States. Evidence-based science, however, may not include all the relevant stakeholders and the interconnected problems they introduce into a problem matrix. This process failure can be seen by examining the Northwest Forest Plan (NWFP), developed in the early 1990’s during the Clinton Administration. The plan called for a settlement of the conflicts between commercial logging on federal lands, rural communities dependent on revenue produced by timber cutting on public lands, and the Northern Spotted Owls endangered by the cutting of old growth trees. The Plan was designed to address conflicts on National Forest lands located on National Forest and Bureau of Land Management Districts in Washington, Oregon, and California[17].

Development of the NWFP included over 600 scientists who put forth strategies for all forest species and called for the use of ecosystem management on National Forest lands; Ecosystem management explicitly links the natural and social systems [2]. Despite the high number of scientists and the use of a systematic management approach, the NWFP ultimately failed because it was designed to develop a solution only for federally managed public lands and did not address the landscape of diverse stakeholder communities impacted by the conflicts. The NWFP fractured stakeholders into two divisive groups: Environmentalists who wanted protection for the Northern Spotted owls and old-growth forests; and Forest professionals/rural communities who worked as loggers, truckers, and operators at local timber mills. Voices that were not included were the forest professional/rural communities who faced a significant impact on their local economies since the NWFP decreased timber cutting by 80% from the National Forest lands [18]. This cultivated a toxic situation in which stakeholders were discouraged from engaging with each other. The problem continued to fester but was not resolved.

The 1994 Northwest Forest Plan was a solution designed to protect old growth forests, endangered species, and provide a predictable level of timber harvesting from National Forests to support the economies of rural communities [17]. However, the NWFP failed to address economic and social goals because it did not include all the relevant stakeholders and include the tradeoffs each stakeholder group needed to make. The Plan focused on responding to a problem that a court injunction triggered, e.g., halting timber cutting in National Forests to address the protection of endangered or listed species by the Endangered Species Act (ESA). Spies, et al. [19] identified key findings of the 1994 Plan that explain why it could not achieve its goals - “threats to biodiversity lie beyond the control of federal land managers” and a clear need for collaboration among the multi-stakeholder communities. To address the economic and social goals would have required a collaborative process among multiple stakeholder groups and the diverse array of landowners who were all impacted by the decisions to protect endangered species.

A follow up story to the 1994 Northwest Forest Plan emerged 26 years later but on Washington State trustee lands. A lawsuit was filed in late 2019 and early 2020 by a timber trade group and an environmental coalition against the Washington Department of Natural Resources (DNR) [20,21]. In the lawsuit they argue that DNR is not adequately meeting its fiduciary responsibilities to rural communities by the level of timber they were cutting from Washington’s trust lands. The rural communities involved in the lawsuit are the same groups who were actively involved in the early 1990s National Forest conflicts that failed to address the economic and social impacts on rural community livelihoods. If the early 1990s planning process had been holistic, and not a top-down approach to assess the tradeoffs between different stakeholders impacted by the Plan, this problem would not be re-emerging today.

These conflicts reveal the juxtaposition of urban and rural environmental values. Bonnie et al. [22] note that rural communities have a stronger place-based identity compared to urban or suburban Americans. This report also identified different environmental issues that rural communities prioritized and felt needed protection. They also found that rural communities prefer policy to be “overseen by state or local government and that allow for collaboration with rural voters and stakeholders” [22]. Their prioritization of local expertise is also reflected in preferences of new Sources. Since the 1980s, the public had become more skeptical of journalism, characterizing it as being more biased, less honest, and not caring about the public [23]. Many Americans prefer to get their news from local media outlets that they trust more than national news outlets [24]. This means that community centers are more trusted, be it the rural communities or in the urban centers. This finding reflects a greater trust of local knowledge and is why the appropriate voices need to be heard when framing problems around multi-cultural and diverse landscape ownership patterns. Resolving environmental issues that are experienced and perceived differently should be guided by stakeholder approaches in a bottom-up manner. Without the incorporation of stories and perspectives of all appropriate stakeholders, conflicts will continue to persist even with legal settlements.

As local communities were developing greater skepticism about journalism, so too did their criticism of environmental credibility. The Shallenberger and Nordhaus [25] essay, entitled ‘The Death of Environmentalism’, presented a very negative view of western environmentalists and its decadal years of failing to include humans and economic development in addressing climate change impacts on the environment. Cohen [26] summarized how the Shallenberger, and Nordhaus essay defined environmentalists as addressing issues too narrowly, not engaging with the public concerns on environmental issues, and not responding to the political interests held by the environmental organizations. This has contributed to the public not being engaged on environmental issues [27]. This is the foundation of Western environmentalism that, to this day, neglects and disrespects local voices of community members as well as long-term indigenous knowledge of nature [28,29].

Environmental mismanagement also proliferated and created unintended consequences for forest professionals/rural communities as the public turned away from the forestry profession and how they managed forests for a singular purpose. This caused the emergence of a new story of how to manage forests, i.e., ‘New Forestry’. In the early 1990’s, Forest Service scientists and academic researchers led the change in forest cutting practices towards longterm health and productivity as well as national forest management agencies adopting the cosystem management paradigm [2]. Gordon [30] describes this paradigm shift as focusing federal agencies to: manage where you are; manage with people in mind; manage across boundaries; manage based on mechanisms instead of algorithms; and manage without externalities. Although the paradigm shifted, the tools to implement ecosystem management were still not adequate and did not include local communities in planning.

The persistence of environmental problems is a result of managers accepting limited solutions to address problems identified by local communities in forests. The Northwest Forest Plan, which was supposed to solve a complex problem in the early 1990s, is a reminder of these inadequacies. Their message was scientific assessments need to incorporate the central stakeholders and derive wisdom from the local communities. There is no singular solution for environmental problems that affect communities differently. They need to be at the center of these discussions and drive our approaches. As we live in this age of massive digital media, it may be difficult to motivate public engagement on environmental issues, though it is the responsibility of environmental leaders in conservation to maintain transparent and malleable practices to the interest of the public.

Environmental Knowledge Formation: It’s Not Just for Scientists

Fundamentally, it is a scarcity of knowledge that is depriving balanced and just decision-making. Natural resource management decisions are made every hour using only a fraction of the facts available for addressing environmental concerns. These decisions are not only made with a dearth of information but also a lacking knowledge about holistic connections which consequently results in poor assessment protocols. These weaknesses contribute to the persistence of local and global environmental problems with no clear solutions in sight. We contend that standard assessment processes and approaches fail to produce viable solutions because they lack holistic connections. These tools tend to simplify a problem as input factors are pre-selected for each assessment; this is well described by Meadows and Wright [31] in their book entitled ‘Thinking in Systems.’ “Scientists and science educators have long wrestled with the challenges of communicating evidence that contradicts people’s personal, religious, or political beliefs, particularly regarding evolution, vaccine safety, and climate change” [32]. In today’s data intensive and technological world of many environmental problems, individuals should learn skills to holistically understand their environment, to be environmentally literate, and to be able to contribute to the competitive workforce of the United States. These approaches are often determined exclusively by evidence-based knowledge provided by scientists. It excludes or dismisses local voices and other sources of credible community knowledge since it is not formed using the scientific method. While scientists offer valuable data and insight, they are only one component of the decision-making process.

Holistic knowledge that enables an understanding of complex systems, and their relationships over variable spatial and temporal scales is crucial for environmental literacy. Indigenous People, however, have a knowledge forming process that provides solutions to environmental issues through long-standing expertise. “The main knowledge-holders of the site-specific holistic knowledge about various aspects of this diversity, Indigenous peoples, play a significant role in maintaining locally resilient social–ecological systems” [33]. Indigenous Peoples are particularly acute at making environmental and natural resource decisions because they are able to prioritize environmental health and cultural issues separate from economic gains. They use holistic critical thinking that includes knowledge held by a tribe for many generations. Indigenous knowledge is transmitted through stories that have a moral [15]. This allows for more ethically grounded environmental literacy and planning. These knowledge forming processes are more adequate for addressing complex environmental issues and necessitates that Indigenous People and those with a place-based lens need to be recognized and engaged as decision-makers for the environment.

When we talk to natural scientists about the holistic knowledgeforming process of Native Americans, we were occasionally asked ‘Where is the science?’ Such a response indicates a lack of recognition for the many different ways of forming knowledge that should be included alongside evidence-based science in the decision-making matrix. Such a question would not be asked if the general public were more engaged in the knowledge-forming process used to assess the sustainability of land and natural resources. Johnson [34] wrote that science should not be owned by a select group of people who indirectly control access to and assimilate knowledge simply because of the degrees they hold or their disciplinary-based jargon that few understand.

From a western world perspective, it probably seems strange to think that one can write stories about science and translate all of its complexities. Western European stories were written as fantasies or imaginary worlds where the ‘good’ people overcome ‘bad’ people and class structure doesn’t matter as a person born on a farm can become the leader of a country, e.g., win the attentions of a princess by being clever and beating the bad people. These stories were not written to tell a morale tale or teach ethical behavior in nature. They were written to entertain the reader and to escape the trials and tribulations found in our world [35]. This contrasts Native American tribes where stories entertain but also deliver a moral held by the community.

Since society is impacted by decisions related to the environment on a daily basis, they need to learn to tell stories on environmental issues to ultimately take part in the formation of knowledge. It’s the scientists’ responsibility to adapt, to grow their skill set to include different modes of knowledge acquisition, and to include the general public in science tutelage. Increasing general scientific knowledge doesn’t take anything away from the need for research scientists to interpret and present our scientific understanding of the environment. However, if we don’t figure out how to situate holistic science in popular culture, the environmental decision-making process will continue to be politicized with researchers isolated in silos, perpetuating the exclusion of local place-based knowledge in environmental discourse. Society ultimately needs the tools to engage in holistic knowledge formation because environmental problems traverse many borders and thus diverse communities around the world experience a multitude of environmental issues.

As Morris et al. [36] write, people are not born with scientific thinking skills and learn these skills as they are “scaffolded via educational and cultural tools.” Therefore, tools are needed to easily and critically contextualize science knowledge and to develop a process that teaches these thinking processes to citizens even without specialized science degrees. Building a new approach is senseless since Indigenous people have taught the skills discussed in the NRC [37] report to their youth for hundreds of years. Indigenous knowledge weaves understanding of the natural world through storytelling and engenders necessary holistic skills of creativity and problem-solving skills that young children need to know. These efforts reinforce a fundamental shift from training environmental technicians who tweak a small part of the landscape in response to a problem to producing environmental leaders who are able to contextualize a problem.

Native People also have a remarkable approach to environmental education that is grounded in long-term knowledge of the land and waters through understandings of reciprocity and dignity for the natural world. Native youth develop environmental literacy skills as they grow up and are commonly taught to think of seven generations and ask how past generations would have addressed a problem [15]. This education instills bottom-up approaches to the environment that focus on describing each problem in a holistic, interdisciplinary lens that creates cultural foundations. This thinking has resulted in the prominent inter-tribal collaborations in restoring and protecting critical salmon habitat in the Pacific Northwest (PNW) U.S. [38]. Regretfully in most communities today, we are not teaching our youth the environmental leadership skills and tools that they need, but rather persisting to educate environmental technicians who will consistently produce the same solution for every problem. Current technicians gather data that are not contextualized to the problem and unfortunately frequently address the symptoms of the problem using a narrow set of prescriptions commonly mandated by a single organization or agency. In contrast, strong environmental leaders use a contextualized lens that is based on place-based knowledge that interconnects multiple factors: cultural values, the environment, health and conventional economic valuation.

Probably the most important factor why we need Indigenous stories today is that they have a knowledge system and cultural traditions that give them an early warning that an environment is not in balance or will be negatively impacted by climate change. In Australia, aboriginal knowledge has been used to manage lands before climate change impacts were evident to scientists, e.g., using fire to manage grasslands so kangaroos and other animals would have nutritious, green grass during a drought [39]. Their traditional hunting practices fostered a diversity of animals surviving in nature and their removal as managers resulted in the extinction of many species [40]. Leonard et al. [41] describe how the Gija people “believe changes in the weather result from human activity and are not a matter of change.” and tell stories explaining the weather events that they experience. When Leonard et al. [41] asked the aborigines to explain why a land was not productive and had dried up, they explained it as the loss of traditional owners who knew how to manage the land and water. Their knowledge goes back thousands of years and is holistic. Recently aboriginal knowledge has been used to develop Indigenous climate change adaptation planning to address future climate change impacts [41].

Science Literacy is an Information Problem

There is a perception that assessing and analyzing large data sets are something that scientists should provide after they have completed many years of training and education. Scientific knowledge is generally accepted by decision-makers because standardized statistical criteria are used to validate the truth of predicted outcomes [15]. This propagates the perception that knowledge formed by the general public or passed down through stories are not realistic or credible unless proven true through the scientific process [42]. But holistic environmental stories are harder to tell using the western science method because it only includes a subset of the information. Therefore, due to the scarcity of knowledge, the underlying cause of the problem or its surrounding interactions are not revealed. Since in the scientific methodology the endpoint is always premeditated, the process can be adapted to reach the pre-defined endpoint. If guided by the correct pedagogical platform, we contend that individuals can be taught to use technological tools to assess complex environmental problems in a holistic manner, i.e., contextualize within environmental dimensionality.

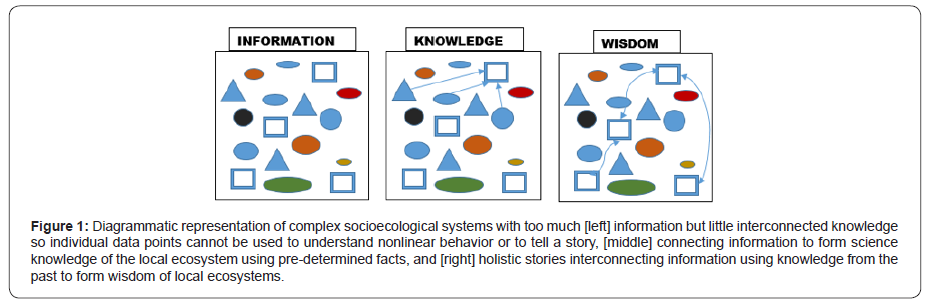

Holistic knowledge-forming process as practiced by Indigenous people address one of the challenges that western scientific method has not resolved, e.g., converting massive amounts of digital data into environmental wisdom so these problems do not persist for decades. This is especially important today where the public do not have the tools to decipher and form data interconnectivities. The title of this paper describes this situation well - “Information Paradox: Drowning in Information, Starving for Knowledge” [43]. The comparison of the differences between information, knowledge, and wisdom is diagrammatically shown in Figure 1. Attempting to form knowledge without understanding the strengths of the connections between diverse pieces of data is not very useful. Similarly having knowledge based on only one part of the system does not allow you to make trade-offs for a problem. Holistic storytelling links environmental problems across time and space, including all the problems linked to it and encompassing all stakeholder groups impacted by the problem. (Figure 1).

Living in the industrialized world has detached us from the land and thus our ability to understand and tell wisdom stories from the massive amount of information we are exposed to each day. The linear approach does not work primarily because it presumes that we have sufficient knowledge to form solutions despite our incomplete, or lacking, knowledge of any given issue. When most of the authors of this article were growing up, stories and TV shows used to have more morals in them. Now much of what is offered today is banter and slapstick comedy. This strays away from some of the most intricate ingenuity that has grounded histories, cultures, and identity for ages. Environmental literacy or just decisions do not work in a linear storytelling world since it moves us to a predictable and predetermined end-point. In many instances our society has promoted linear stories only to realize later that these narratives are telling a mere fraction of the actual story and has even advanced us in the wrong direction. An iconic example includes Smokey the Bear (Figure 2), an icon created to sell a story which was incredibly successful in pushing the United States towards a policy of complete fire suppression. Unfortunately, we did not incorporate into the story available knowledge from generations of Native Forest stewards of this land who used fire as a means to keep the forests healthy. Today we are still remediating the problems wrought by this misinformed policy of fire suppression (Figure 2).

Teaching science literacy today needs to teach “the interconnected nature of fundamental concepts for earth, space, life and environmental sciences” [44]. Since science is taught using a narrow disciplinary lens, it de-contextualize information and thus is unable to teach science literacy skills to the nonscientific community. As Reyes-García et al. summarized: “scientific knowledge … goal of being universal, transferable, mobile, and not tied to a singular place.” This is a very linear thinking approach to forming science knowledge where some disciplines dominate the discourse. This mental construct of science today can be viewed as a seesaw that moves you up and down at the same spot and leads a decision-maker to adopt a pre-determined endpoint or solution. In contrast storytelling allows a community to form holistic view of the world “emphasizes the historical continuity of such bodies of knowledge, not only their local embeddedness, but a characteristic also that seems to contribute to the long-term resilience of social–ecological systems by providing a pool of information and practices that improves societies’ adaptive capacity to cope with recurrent environmental or social disturbances” Reyes- Garcı´a et al. 2016. Indigenous stories already include multiple interconnections between “earth, space, life and environmental sciences” [28]. Linear approach to science is difficult to use to tell stories of interconnected knowledge. Indian Country Today (2018) describes these differences: “With linear thinking, we rely on logic, institutions, and others to try to protect ourselves. Circular thinking originates from the earth, the universe, and the Creator; we are all connected and all safe.”

Native Oral Storytelling Traditions of Nature

Storytellers, like the Native American tribes, tell holistic stories about their environment that are grounded in place, values, and principles [15]. In his 2012 book entitled Storytelling Animals: How Stories Make Us Human, Gottschall wrote that stories are what makes us human [34]. Stories are what ground us to each other and connect us to our histories. As King writes in The Truth About Stories, “that’s all we are” [45]. Stories inherently shape the ways we see and know the world as well as how we live in it.

Native people’s stories are similar to a mystery novel where pieces of evidence suggest who are the ‘bad’ players while revealing bits of information that ultimately reveal knowledge to recognize who are the guilty parties. It was also a way to tell a story that could have several different endings, so they became learning moments for tribal youth to learn to respect nature, how to live on the land that includes its cycles of change, and how to read the land to reduce its vulnerability to land-uses. In Native American stories, animals and humans can transform into other shapes [46] and conclusions are not predictable or repeatable. Sometimes the coyote - a trickster - is a common animal in these stories as described by Jay Miller [46]: Native Americans have long oral traditions that transmit knowledge that is transgenerational and may include descriptions of natural phenomenon that are important to know to live in balance with the natural world. They continue their storytelling practices, even after they were forcibly removed from their lands. Oral storytelling has kept their customs, values and languages alive within the tribal community.

It is important to recognize that the characters of the story are not as important as the knowledge that is being transmitted by the story. For example, there is a Native American Wisdom Story about how before the arrival of humans, the world was dominated by a monster who was eating all the animals in its path. The coyote tricks the monster into swallowing him after he had gathered some flint and a knife, so he could then set fire to the monster from within to kill it (Figure 3). The monster Wisdom Story is highly relevant for today’s society even though a monster aimlessly swallowing animals has no literal connections in today’s world. Many Indigenous stories are expressed similarly through a context of relationality, orienting the reader within a world of networks and connections [47]. Through this interpretive ambiguity, each individual can therefore “generate meaning within their own lives” [48]. This is particularly true when positioning the reader through the lens of the trickster. In this story – the coyote who can be good, or sometimes bad, uses a novel approach to kill a monster and save many animals (Figure 3).

Similarly, the Nordic tales have a trickster – Loki – who was jealous of the Nordic Father God’s son, Baldur. The story recounts how Loki tricks the blind brother of Baldur into killing his brother using a piece of mistletoe. This is a story that describes how even a small and insignificant thing – in this case, the mistletoe – should not be ignored. The trickster serves as a change element that drives the story in a different and unpredictable direction. Many contemporary stories would benefit from this model as they tell predictable linear narratives that give security and closure, ideals that we find comfort in. The inclusion of a trickster in stories reflects the unpredictability of life and demonstrates that we must learn to be amused by the antics of a trickster while expecting these unexplained events. We can’t control the environment and embracing the story element of a trickster can help emphasize such valuable take home messages.

The Creation Stories told by past societies more than a 1,000 years ago are just as relevant today as in the past. These stories frequently include a tree at the center of the world and recognizes the importance of trees for human survival. Trees are used as symbols of science, culture, politics, religious enlightenment, and knowledge: Ancient Egypt incorporated the Sycamore tree in their stories, the Ash tree is found in Nordic mythology, the Mulberry tree in China, the Oak tree in parts of Europe, Buddhists have the Fig tree, the Montezuma cypress in Mexico, and there are many more examples from around the world. To understand why trees are central to so many creation stories, it is vital to realize the resources that all trees provide to societies: medicinal products, foods, spices, heat, rubber, chewing gum, insect repellent, housing, and even hallucinogens [49]. Arguably, the most important role of trees is that you will find fresh drinking water where you have trees, i.e., today 75% of the world’s freshwater comes from forests and 90% of the world’s cities rely on forest watershed for their water [50]. There are plenty of reasons to tell stories about forests globally.

Embedded in these stories are tales of the importance of respecting nature and managing environments as an ecosystem. The terms used to describe the science of forest management are derived from Silvanus-a Roman God of Forests, Groves, and Wild Fields— who presided over those parts of nature and had knowledge on how to cultivate a forest [51]. Trees included in these stories lived for over 1,000 years and provided survival resources for multiple generations of people who learned about them through stories passed down through the generations.

Tree stories need to be told in our global industrialized world where many lack any knowledge of forest products or forest ecosystem services. This leads to the over-exploitation of these resources due to ignorance and lack of environmental literacy. Many trees mentioned in creation stories are endangered today, and, except for the local people who value them, the rest of the world frequently doesn’t know about them or value them. For example, the Dragon’s Blood tree is only found on a remote island known as Socotra off the coast of Yemen and was first discovered by the East India Company in 1835 [52]. According to legends, the first tree was created from the blood of a wounded dragon and, correspondingly, the latex released by the tree’s bark has medicinal values for local people [53]. Today, the latex from Dragon’s Blood trees is sold in international markets as a cure for many human ailments [54]. Unfortunately, these trees are now endangered and over-exploited as a result of ignorance and miseducation.

Creation stories often focus on trees that are important survival resources for indigenous communities. One only needs to look at trees that were and are still revered [55]. One positive outcome of the creation stories is that they commonly set rules for how society should function related to nature. This lessens the chances of assured societal collapse when nature is over-exploited beyond its carrying capacity. As an example, some of those rules fostered the establishment of sacred groves by the societies such as the Hawaiian wao akua or the Ethiopian hujub [56].

These sacred groves are areas of land and forests protected and revered by the local communities. Some sacred groves have persisted for over 1,000 years while, in contrast, protected areas managed by western science have been around for 150 years and are often fraught with conflict. Will the western protected areas still be around in 50 years when no local community respects and protects them for the survival resources they provide?

Storytelling provides us with an opportunity for a holistic understanding of our natural resources and a more engaging one as well. Storytelling is a door to provide us environmental leadership that communicates complex knowledge that needs to be part of the world’s global culture. It is not the property of a select group of people but needs to be practiced by all of us since nature is not a bounded system controlled by a small group of people for their own benefit. It may seem that we are no longer interested in contextualizing the information that is so readily fed to us through digital media, though humans are originally storytellers. It was forecasted several years ago that Americans would no longer read printed books in the future as they would be considered old fashioned/old technology; but this demise has not occurred. In fact, Americans still prefer to read printed books and at an even higher level than books in digital format [57]. This provides some evidence that society has not shifted into only living with, and learning about, what is dictated by the digital media. Utilizing contemporary techniques to storytelling through digital media may be the future for environmental engagement in popular culture.

Concluding Remarks: Indigenous Holistic Storytelling - A Critical Element for Environmental Leaders and Policy Makers

There is a widespread perception that the stories and cultures of past societies are fictitious and less relevant today because society has progressed so far, and we now live in a globalized world. What is culture when we live in a society where environmental stories are written and packaged by people who are not part of the community? What happens when stories do not organically emerge from their community and are instead manufactured by an outside culture comprising very different values? If we are going to solve local environmental problems so they do not persist for decades, learning native oral storytelling traditions is crucial to form wisdom from massive amounts of data that technology delivers us daily. Some suggest that Indigenous People are no longer linked to their land and tribal community since so many live-in urban areas. Data show that 78% of American Indians and Native Alaskans live outside of reservations or off-reservation trust lands in 2010 [58]. Despite this, urban Indians continue to return to reservations to maintain a link to their cultures and make decisions using the consensus-based decision-making process employed by most tribal councils in the PNW U.S. Native communities live in both worlds – within the global economy as well as their local cultural environment. For Native People, reservations maintain community, culture, and their stories. For these reasons, the loss of culture may not be as widespread as some people think.

Pacific Northwest tribes are successfully providing leadership on environmental and resource issues; most issues cross geographic and political borders and are important for all of us in the pursuit of biodiversity conservation and a healthy environment. They are using the knowledge passed down through stories intergenerationally and youth learn about sacred places, conservation, and wildlife. When this knowledge is not part of environmental management, animal populations may go extinct [40] or we lose the tools to manage the negative impacts of climate change on the environment. Indigenous and local people are effective at providing early warning of climate change impacts before scientists recognize that an environmental problem is looming [59]. Without including the holistic stories of Native communities, we face a scarcity of knowledge to address climate change issues or recognize that a problem is emerging.

Our greatest challenge today is how few people are literate in a holistic science decision process. Students, citizens, and politicians lack the science literacy skills needed in today’s information economies [36]. Science literacy is not just being able to remember facts but an ability to critically evaluate, contextualize, and determine what science data are needed to address a problem generated in our information world. Science literacy in education has been described as teaching “adaptability, complex communication/ social skills, nonroutine problem-solving skills, self-management/ self-development, and systems thinking” to meet the challenges imposed by our 21st century information economies [37]. Most educational programs do not teach these skills [60]. Thus, science knowledge becomes the ‘hidden half’ of the information economy.

Even when decision-makers recognize they need to include science in solving an environmental problem, it is too narrowly defined so its ecological, social or cultural scale and context are not made transparent. It is not an option to avoid including the sciences in today’s information-based economies since “science is part of the wonderful tapestry of human culture, intertwined with things like art, music, theater, film and even religion.” [34]. Science literacy is not just for scientists but contain essential skills needed by students, citizens and politicians. People need to make decisions in a realm where science, technology, engineering, math and the arts all intersect [12].

Youth need to become environmentally literate but are less attracted into science fields in the U.S. Science education needs to attract a more diverse group of students and to keep them engaged in the educational process. Science education should consist of youth helping to create knowledge instead of just being given knowledge they need to learn. Not only scientists need skills to address science-based problems, but non-science employment sectors need employees who are grounded in STEM education knowledge [69]. Private sector businesses also want to hire employees capable of applying “abstract, conceptual thinking to “complex real-world problems—including problems that involve the use of scientific and technical knowledge—that are nonstandard, full of ambiguities, and have more than one right answer” [70].

Many students do not link science literacy to be gainfully employed in today’s information economies. It does not help that market economies have a poor record of accomplishment concerning environmental issues and sustainable consumption of natural resources.

Certain demographic groups (e.g., Hispanics, African Americans, American Indians, and Alaska Natives) who have a family or clan history of looking at the environment holistically are not attracted into STEM educational programs; they account for a quarter of the U.S. population but 11% of STEM degree holders [71]. Few STEM programs are contextualized to include holistic forms of knowledge, e.g., spiritual as well as art, plants, animals, geology as well as physics, or tools to critically think about knowledge across disciplines. The concept of STEM has been modified to integrate with the Arts in education and we suggest that this should be further expanded to iSTEAM or Indigenous STEAM. This is the case we hope to make in this article.

Today, climate change may finally push us towards recognizing alternative knowledge streams to solve environmental problems; scientists globally and the European Union are calling this a climate emergency that urgently needs solutions [61,62]. When societies have taken a narrow view of their environment or over-exploited their resources, they collapsed (e.g., the Khmer Empire, the Maya, Nazca) [63-67]. Collapse is not an option but adopting new ways to form holistic knowledge is a viable option. Despite advances in scientific knowledge, environmental problems have continued to persist for decades, with the exception of a few sparse success stories. This is paradoxical since, in the industrialized world, scientific knowledge has built our information economy. Today, the fragmented use of science to teach science literacy does not allow science knowledge to be used effectively to respond to environmental, economic, and social boom-and-bust cycles [5,12]. Also, the standardized tools commonly used in the sciences are not designed to “…acknowledge the value system and cosmological context within which this traditional knowledge was generated” [68] and therefore unable to integrate indigenous knowledge except as a narrative in research.

To help resolve environmental problems in a shorter time with long-lasting solutions, we need to teach society a process to contextualize the massive amounts of data delivered by mass media. Society needs to process and engage with this massive data holistically by scripting stories of environmental issues. This is environmental literacy utilized by Indigenous people since time immemorial to maintain sustainable relationships with the land. Indigenous storytelling serves as a model for non-Tribal people to develop comprehensive understandings of the environment and thus more effective management solutions. We believe that by teaching individuals, especially youth, digital environmental storytelling, we can help guide society toward a holistic perspective for solving complex environmental challenges. When more members of our society begin intuitively considering multiple angles of an environmental issue and accepting the unpredictability of the environments around us, it will be much easier to solve our environmental problems and put us on the path to making even better decisions for policymaking.

Acknowledgment

None.

Conflict of Interest

No conflict of interest.

References

-

Kristiina A Vogt, Alexa Schreier, Alishia Orloff, Michael E Marchand et al. Building Environmental Literacy through Holistic Storytelling. Online J Ecol Environ Sci. 1(1): 2021. OJEES.MS.ID.000501.

-

Too much environmental information, Decontextualized management, Indigenous, Local knowledge, Holistic stories, Wisdom deprivation, Indigenous steam

-

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.

- Abstract

- Communities as our Source of Knowledge

- Ineffective Environmental Problem Definition: Northwest Forest Plan Example

- Environmental Knowledge Formation: It’s Not Just for Scientists

- Science Literacy is an Information Problem

- Native Oral Storytelling Traditions of Nature

- Concluding Remarks: Indigenous Holistic Storytelling - A Critical Element for Environmental Leaders and Policy Makers

- Acknowledgement

- Conflict of Interest

- References